6—

Concentrating Resources on Highway Development

Of the many public and private activities that shape the metropolis, transportation developments are perhaps the most significant. The rail lines that spread across the countryside from the largest American cities in the latter nineteenth century, together with streetcars, elevated trains, and subway systems, were powerful forces in determining the patterns of residence, employment, and recreation in urban areas. Similarly, during the past sixty years urban America has been reshaped by the automobile, the bus and the truck, and by the vast highway network that serves their needs as it encourages their proliferation. New highways, thrusting into unsettled areas, attract developers who convert farmland into suburbs and inspire the movement of businesses as well as erstwhile city residents into the outer reaches of expanding metropolitan regions. Changes in urban transportation also modify recreation opportunities and other aspects of the urban environment. New rail lines and highways have prompted the creation of parks and resorts; expansion of the road system has threatened wildlife refuges; increasing numbers of automobiles and buses generate air pollution problems throughout urban areas.[1]

No one seriously contests the view that transportation developments have had an important impact on metropolitan America. Nor could it be argued that government is a mere spectator in the evolution of transportation facilities. State highway departments and regional turnpike authorities across the nation have financed and constructed bridges, tunnels and highway networks, and the federal government has been heavily involved in funding these facilities. State and federal agencies regulate rates, routes, and conditions of service for railroads, trucks and buses. City governments were owners and underwriters of early streetcar and other municipal transportation enterprises. More recently, direct public subsidies have helped maintain commuter railroad service as well as subway and bus service in the Boston and New York areas. New York State has taken over complete ownership and operation of the Long Island Rail Road, and government agencies have underwritten the

[1] For detailed consideration of urban transportation developments in the United States and their impact, see Sam Bass Warner, Jr., Streetcar Suburbs (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press and MIT Press, 1962); Wilfred Owen, The Metropolitan Transportation Problem (New York: Doubleday, 1966); Edgar M. Hoover and Raymond Vernon, Anatomy of a Metropolis (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1959). especially pp. 215 ff.; and Alan Altshuler et al., The Urban Transportation System: Politics and Policy Innovation (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1979).

construction of new subway routes in the nation's capital and in other urban regions.

What has been asserted—in fact, what has been a widely held scholarly view—is the argument that government organizations involved in transportation are unimportant with respect to shaping urban development because their actions are not independent. These agencies, particularly those involved in highway transport, are viewed as inconsequential because "they leave most of the important decisions for Regional development to the private marketplace."[2] Our general position, that this oversimplifies a complex pattern of relationships, has been set forth in Chapter One. In this and the following chapter we examine these relationships in urban transportation more closely.

It is true, of course, that major transportation developments are not simply the result of governmental action, and that activities in the private marketplace are among the most important influences in shaping urban transport networks. While the same conclusion applies to a wide range of urban development projects, the transportation system illustrates the interconnection of factors particularly well. But if the activity of governmental organizations provides only one of many factors, is there any way to sort out the causal linkages? Can we identify evidence that bears on the question of whether government's role is merely to facilitate the achievement of goals determined elsewhere (especially in the private marketplace)? Or, alternatively, do government agencies in the transportation field have a significant role in shaping development?

The discussion in Chapter One suggests two modes of analysis that may be useful. One would explore cases where governmental agencies preferred different outcomes from those desired by other actors, in order to determine how often and under what circumstances government organizations "win"—that is, how often their actions significantly modify private-marketplace behavior. That approach was especially useful in Chapter Three, where zoning and other land-use regulations were found to conflict with unhindered (preferred) buyer-seller relationships regarding the sale and use of land for residential and commercial uses, with such regulations affecting locational patterns in important ways.

But that approach is not very useful in analyzing government's role in highway development during the past fifty years. In the road building era, the goals of the main consumer groups (users of automobiles, trucks, and buses) and private-sector producers (motor vehicle manufacturers) generally paralleled the goals of the major governmental agencies—the highway departments and road-building authorities. For all of these groups, the primary goal was more and better highways, tunnels, and bridges for motor vehicles. This similarity of goals lends plausibility to the view that governmental actions simply "abet the economic forces already at work," so that public programs are "of little consequence" in regional development.[3]

In this arena of governmental action, we can, however, make use of the

[2] Robert C. Wood, 1400 Governments, (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1961), p. 173.

[3] Ibid., p. 175. Quite different urban transportation goals were put forward by other groups, such as rail transportation organizations (public and private) and rail commuter associations. See discussion in Chapter Seven.

second mode of analysis described in Chapter One. That is, we can explore the perceptions and motivations of the main governmental actors in order to determine whether they are simply facilitating the interests of private transport users and producers, or whether their actions are shaped (partly or largely) by other concerns. Insofar as other concerns are important motivators, a governmental agency can be said to be an independent force in shaping urban development. Moreover, when government decisions—whatever their motivation—have an important role in the location and timing of crucial transportation developments, it is doubtful that such public programs should be characterized as being of little consequence.

This chapter explores the capacity of highway agencies in the New York region—based on areal scope, functional specificity, and the ability to concentrate resources—to determine the location and timing of major highway projects, and their motivations in using these sources of influence. The discussion includes more detailed scrutiny of several especially significant transportation projects of the past fifty years—the construction of the Holland Tunnel, George Washington Bridge, and Port Authority Bus Terminal; and the studies in the 1950s of highway arteries throughout the region, resulting in the building of the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge and other important additions to the highway network.

To many observers of urban development, the highway agencies have seemed too dependent—too responsive to the pressures from automobile associations and other highway user groups, too ready to build still more highways and bridges when traffic volumes increased or roads were criticized as outmoded. At the same time, the road and turnpike agencies have been too independent—far too reluctant to coordinate their plans with those of regional planning and rail organizations, and too resistant to cooperation in financing arrangements that would ensure the vitality of the regional transport system as a whole.[4] The campaign to harness the Triborough and Port Authority, the state highway department, and their brethren to a chariot labelled "coordinated metropolitan transportation," and to tap their healthy treasuries to assist the ailing mass transit system, began before World War Two and still continues. There have been a few victories, some symbolic, some real. As a result, the region's rail and bus services have been partially stabilized, or have declined more slowly since the 1950s than they would have in the absence of new government initiatives; and these actions have had some influence on the distribution of residences in the region, and on the concentration of employment in Manhattan and other urban centers. The next chapter reviews these continuing efforts to maintain a viable mass transportation system in the New York region.

Contenders for Influence

The actions of a public agency to build a turnpike, subsidize a railroad, or carry out any transportation program are imbedded in a complex pattern of

[4] See Owen, The Metropolitan Transportation Problem, especially Chapters 3–6, and Wood, 1400 Governments, pp. 123 ff., 173–175, 192.

human activities and preferences, some proximate and others more distant in time and place. Other forces also are at work. As noted in Chapter Two, technological change and topography strongly shape the transportation system. The impact of technology is illustrated by the invention of the internal combustion engine, which made possible the creation of an efficient motor vehicle, and by the development of manufacturing methods that require more horizontal space, impelling businessmen to seek suburban locations where such space is available more readily and at lower cost. In the New York area, the role of topography is seen most prominently in the major waterways that divide the metropolis. The Hudson River, the East River, and New York Bay long retarded the construction of rail and highway facilities to join various parts of the region. Their existence also helped to induce public officials to create new agencies that could concentrate resources in order to overcome these obstacles to commerce and general mobility in the region.

Another key factor is public demand—the demand for highways and other transportation facilities needed to achieve desired travel objectives, especially the minimizing of congestion and travel time. As noted in Chapter One, the pattern of transportation demand in recent decades has been shaped by widespread interest in greater privacy and open space. When combined with increases in per capita income and automobile ownership, these preferences have generated greater effective demand for housing and recreation in the suburbs, thus adding to pressures for more transport facilities, particularly to serve automobiles. These pressures have been exacerbated by substantial population growth in the suburbs, and by the dispersion of manufacturing plants and other employment centers in the decades following World War II.[5]

In general, then, public demand has been a significant causal factor in the expansion of highway, bridge, and tunnel facilities. In the New York area, residents have also shown declining interest in using rail and subway services, especially during off-peak hours. Yet there are exceptions that demonstrate the interconnections among factors shaping transportation patterns. For example, Long Island's shape and the barrier of the East River have restricted transportation corridors from Nassau and Suffolk into New York City, so that the major rail system serving the area, the Long Island Rail Road, has attracted a high and fairly stable volume of passengers throughout the past two decades.[6]

In addition to technology, topography, and consumer demand, transportation development is affected by the activities of a wide variety of governmental agencies and organized private groups. While some of these organizations are not primarily interested in modifying the transport system, their

[5] See, for example, Raymond Vernon, Metropolis 1985 (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1960), especially Chapter 9, and Benjamin Chinitz, ed., City and Suburb [Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1964).

[6] The annual passenger volume on the Long Island Rail Road declined from 75 million in 1956 to 69 million in 1961, rose into the 70 millions in the 1960s, fell to 69 million in 1971, was 66 million in 1974, and increased slightly in 1976 to 67 million. The past four years have seen greater increases in ridership, and the 1980 total was 81 million.

actions may have a crucial impact. Among the most important in this category are residential developers, business firms, and municipal governments, whose zoning and other land-use decisions influence the location and density of residences and the distribution of employment centers, and as a consequence affect transportation demand. Other political actors are directly concerned with shaping the transport network in the context of a broader set of social-development goals. In this category are such organizations, discussed in Chapter Five, as the Tri-State Regional Planning Commission, the Regional Plan Association, and the governor's office in each state.

The final category of contenders for influence are governmental and private organizations primarily concerned with construction, operation, and regulation of transportation facilities. Our main interest in this chapter and Chapter Seven is with public agencies in this category, whose activities range from minimal, stop-gap actions in response to immediate pressures from other sources, to a significant role in determining the pattern of transportation (and therefore the pattern of urban development) in the region. The more modest role is illustrated by the actions of state and federal regulatory agencies, confronted with demands from private railroads or bus companies to increase fares or reduce service because of declining patronage, and with opposition from commuters using the service. In this situation, the regulators have generally been limited by statute and tradition to a rather passive role. They receive requests from the private companies, weigh the proposal's impact on the users (as well as the prospects for political retribution from the users), and usually grant some portion of the change requested.

Far more significant are the actions of government agencies to grant substantial subsidies to private rail and bus corporations, or to purchase and operate rail and bus lines so that service can be maintained and perhaps expanded. New York City's decisions during the Depression to buy the several subway and elevated lines, and the purchase of the bankrupt LIRR by a state agency in 1966, illustrate an important governmental role—assuring continuation of rail service in major sectors of the region.

In highway transportation, the government role has also varied widely—from the important but highly constrained function of deciding which route will be used in meeting increased traffic demand in a particular corridor, to developing major new projects with widespread effects on transportation patterns and land development, such as the George Washington Bridge in the 1930s and the Narrows Bridge in the 1960s.

To demonstrate that governmental agencies have in fact had an important role in determining the pace and direction of highway development, we can—as suggested in the opening pages of this chapter—direct our attention to questions of motivation and of location and timing. As to motivation, available evidence demonstrates that the policy decisions and programs of the major highway officials in the New York region were not simply responses to the demands of automobile drivers, trucking firms, and others interested in expanded vehicular facilities. Their actions have also been shaped by desires for institutional growth and personal prestige. To be sure, enhancing their own power required sensitivity to consumer demand and to social values held by the region's publics; it also required manipulating valued symbols to mod-

ify public pressure in ways that would permit and encourage the growth of their own organizations. Formal structure, leadership skills, and tax and revenue dollars were ably bent to this task.[7]

Even if public officials intended simply to let consumer demand determine their actions, in the complex arena of regional highway politics their responses would inevitably not be "simple." The timing and location of highway developments are not mandated authoritatively in the marketplace, and determining a project's feasibility depends on governmental calculations and cooperation that inevitably must shape the direction and pace of settlement in any large urban region. Thus the Narrows Bridge was completed in the 1960s, rather than in the 1920s or 1980s; and the 125th Street bridge across the Hudson was not built at all. The decision to go forward with the first was consistent with consumer demand for more arterial facilities; the decision against allocating funds for the second was not. Both actions were based on calculations of benefit and cost made within staff offices of two transportation authorities, using a set of rather narrow assumptions that were barely understood by other interested parties, public and private. The negative decision on the trans-Hudson bridge was reported by the Port Authority and Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority in 1955, but was never considered in detail outside the constellation of transport agencies—perhaps inevitably so, given the complexities of financing priorities and traffic flows that typically shape program decisions.[8]

In general, the more complex and expensive a project is, the less likely that simple consumer demand will be the determining factor. This can be illustrated with an example from the field of sewerage. If a homeowner in a rural area decides to replace his outhouse with a septic tank, he solicits bids and decides which tank best meets his standards of quality and price. The private market has responded to his consumer demand. But when a developer seeks approval for a new sewer trunk to serve a 50-acre site for residential housing, he is likely to become enmeshed in a complex pattern of organizational rules and personal interactions—even if there is widespread support for the proposed development. With public works projects of even greater areal scope and technical difficulty, as in the regional highway programs of the 1960s, the complexities and discretion necessary increase exponentially. Feasibility, timing, and location will depend on the planning and negotiating skills of officials operating within large bureaucracies and complex intergovernmental networks, and on their motivation and ability to allocate time and other resources needed to develop and carry out complex projects.

[7] In his discussion of regional agencies, Wood agrees that their behavior should be seen as the result of "conscious design" by agency officials, but their motivation is seen as primarily a matter of survival in a world controlled by the private marketplace: "Considerations of institutional survival often tend toward programs which accelerate trends already underway," and thus the system of regional agencies, like the local governments, "arrive at . . . positions of negative influence." (1400 Governments, pp. 173–74.)

[8] The definitive public reports on the Narrows and 125th Street bridges are found in Port of New York Authority and Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority, Joint Study of Arterial Facilities (New York: January 1955).

The Highway Coalition

In the earlier years that concern us—from the late 1920s through the late 1940s—the agencies involved in rubber-based transportation could hardly be called a coalition. Like nations trying to carve out spheres of influence in a new-found land of riches, the highway agencies sometimes cooperated and sometimes went to war in their efforts to attract motorists and truck drivers. In those more competitive years the motives of leaders and organizations are seen more starkly, and the role of consumer demand must be placed in the context of a quest for power. The battle between the Holland Tunnel commissions and the Port Authority, recounted below, illustrates this phase, as does the often-bitter conflict between Robert Moses and the Port Authority during the 1930s and 1940s.[9]

As areas of influence stabilized in the early 1950s, and the flow of funds from tolls and federal coffers increased, cooperation became the norm, and the dozen major agencies concerned with the highway system evolved into a coalition dedicated to increasing the length and breadth of road facilities, and to resisting efforts of mayors, urban planners, and other "interlopers" to reshape their priorities and plans based on allegedly broader development goals.[10] Conflict among members of the highway alliance was not entirely ended, but disagreements were usually resolved by staff discussion and compromise, without public display of differences.[11]

Underlying the ability of the highway coalition and its members to affect the timing and location of major projects, and to shape arterial programs partly in terms of their own motives, were a number of interrelated factors, which reinforced one another: wide areal scope, skilled leadership, complex and sophisticated bureaucracies, relatively abundant resources, enthusiastic support from narrowly focused constituencies, and—especially for the public

[9] See particularly Herbert Kaufman, "Gotham in the Air Age," in Harold Stein, ed., Public Administration and Policy Development: A Case Book (New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1952), pp. 143 ff. Erwin Bard, the leading student of Port Authority activities in this period, characterized the PA and TBTA as "bitter enemies" during these years. (Telephone conversation, July 28, 1977.)

[10] See J. W. Doig, Metropolitan Transportation Politics and the New York Region, Chapters 2 and 10. For purposes of this discussion, the highway coalition includes the following government organizations as they operate in the New York region: the state highway agencies (in New York, the State Department of Public Works, and in New Jersey and Connecticut, the state highway departments—all three being retitled departments of transportation in the late 1960s); the Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority, which operates in New York City, the Jones Beach State Parkway Authority on Long Island, and other authorities on Long Island chaired by Robert Moses; the Port Authority, whose highway-related enterprises include three Hudson River crossings (the Holland Tunnel, Lincoln Tunnel, and George Washington Bridge), three bridges between Staten Island and New Jersey, two bus terminals in Manhattan, and truck terminals in New York City and Newark; the four turnpike authorities listed at the end of note 12; and the federal government's major highway agencies—the Bureau of Public Roads until 1966 and the Federal Highway Administration thereafter.

[11] There were, however, occasional breaks in the public display of cooperation. For example, when the New Jersey Turnpike Authority announced a plan in 1964 to widen a section of the turnpike from six to 12 lanes, the Port Authority calculated that such an expansion would cause congestion on its trans-Hudson crossings and thus negatively affect its public image and perhaps its financial position; it then opposed the expansion, appealing through the press and directly to New Jersey's governor. The Turnpike Authority's staff and board continued to favor the project, however, and its independent legal and financial position, as well as strong backing from Contractors and construction unions in New Jersey, enabled the program to go forward.

authorities that were coalition members—a relatively high degree of independence in formal structure and in the allocation of financial resources.

From the 1920s onward, central roles in highway construction in the New York region were held by the quasi-independent public authorities—the Port Authority, Robert Moses' Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority and his several parkway authorities operating on Long Island, as well as four separate state turnpike authorities.[12] For these agencies, insulation from partisan politics—and from broader policy direction—was provided when they were created. Under state laws, boards of private citizens, serving part-time, appointed the executive director and other senior staff officials, and were given formal governing power. Moreover, these agencies were required to finance their projects mainly with tolls and rents from their own facilities. Thus two important sources of public control—appointment of top-level administrators by elected executives, and the review and approval of annual budgets by governors, mayors, and legislators—were essentially excluded.[13] In terms of the fourfold division outlined in Chapter Five, the public authorities in the highway field fall in the first category of "highly autonomous" government organizations.

Formal autonomy does not, of course, ensure actual autonomy. Without a large flow of paying customers, a public authority must appeal for tax-generated funds to survive, thus opening a wedge for close supervision of its activities by suspicious state auditors and legislative committees. This issue was well understood by the early Port Authority leaders, and their strategy, discussed below, set a pattern for authorities across the United States. Fortunately for the highway authorities, public demand and agency activities were joined harmoniously in the postwar era, producing balance sheets with large surpluses. For example, the Port Authority's net revenues (after debt service) rose from $15 million in 1950 to $37 million in 1960, and $73 million in 1970, while the New Jersey Turnpike Authority's net revenues reached nearly $40 million in 1970. With these funds available, autonomy in name became discretion in fact, permitting authority officials to weigh choices among widening highways, improving interchanges, building new bridges or major arterials—or even allocating funds to a new arts center, to airport expansion, or to a world trade complex.

[12] The Port Authority was created in 1921; its activities in the highway field began in the late 1920s. The Triborough Bridge Authority dates from 1933, when it was formed to build a single bridge connecting Queens, Manhattan, and the Bronx; the creation and merger of several additional authorities in New York City led in 1946 to the establishment of a unified agency, the Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority, headed by Robert Moses. The Long Island authorities were created in this same period. During the first decade following the end of World War II, the states created authorities to construct new major toll roads—the New Jersey Turnpike Authority, the New Jersey Highway Authority (which built and operates the Garden State Parkway), the Connecticut Turnpike Authority, and the New York Thruway Authority.

[13] In contrast to most public authorities, Port Authority actions were subject to gubernatorial veto. That formal power was almost never used, however, until the mass transit conflicts of the 1970s discussed in Chapter Seven.

For thoughtful studies of public control of authorities in the New York region, see Wallace S. Sayre and Herbert Kaufman, Governing New York City (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 1960), Chapter 9; and Annmarie Hauck WaLsh, The Public's Business: The Politics and Practices of Government Corporations (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1978), especially Chapters 4, 7, and 8. The Port Authority is considered from this perspective in Jameson W. Doig, "Regional Politics and 'Businesslike Efficiency,'" in Michael N. Danielson, ed., Metropolitan Politics, second edition (Boston: Little, Brown, 1971), pp. 111–125.

Choices of these kinds, and the implementation of complex programs, cannot effectively be controlled by boards of part-time officials. It was inevitable, therefore, that actual power would devolve largely on senior staff officials. Moreover, since challenging opportunities were combined with ample resources, the authorities were able to attract men and women interested in developing and carrying out programs that would enhance their organizations' prestige and power, while adding luster to their own personal reputations.[14] So the partial leadership void created by part-time commissioners was quickly filled by able and aggressive staff. And with the development of the large-scale federal highway program in the 1950s, the federal and state highway departments also were able to attract to top positions individuals with an interest in and talent for the effective use of power.[15]

Even if these highway agencies had been led by officials with cramped imaginations and an aversion to the use of power, it would still have been difficult for the coalition simply to abet the goals of consumers in the marketplace. In any large bureaucracy, rivalry and negotiation among departments, staff units, and individuals deflect and modify signals and demands from the marketplace, or other outside sources.[16] And the highway agencies were large and complex bureaucracies, particularly in the road-building era. New Jersey's turnpike authority, for example, had more than 1,400 staff members in 1971. The Port Authority, embracing a much wider range of functions, had already expanded to 3,600 staff members in 1952, allocating these among 15 major departments with 43 divisions. Twenty years later, in 1972, there were 19 departments and 72 divisions, employing a total of more than 8,000 individuals. The other authorities and line departments enjoyed similar growth in the 1950s and 1960s.

But size and complexity were not the most significant characteristics of these agency staffs. In terms of potential for influencing regional development, their ability to attract high-quality planning and public-relations staff members was far more important. Able planning staffs could analyze the dynamics of regional growth and changing travel patterns, harnessing economic and technical data to the agencies' own goals, and providing solid if narrowly focused interpretations of current transportation problems and possible solutions. Moreover, their reports, carefully honed and replete with charts and statistics, could overwhelm the reservations of potential opponents, and gain the applause of editorial writers and governors who admired

[14] For many authority staff members, there was an added dimension: the decision to join a government agency rather than a private corporation was attractive because they preferred to work in the "public service"—in organizations whose resources and goals were presumably harnessed to serve the needs of the region and its people.

[15] In terms of Anthony Downs's typology of officials, these authorities and line agencies attracted climbers (those interested in power, income, and prestige) and advocates (whose motives also include promoting the goals and enhancing the power of their own organizations) rather than attracting conservers (those primarily concerned with individual security and convenience). See Downs, Inside Bureaucracy (Boston: Little, Brown, 1967), pp. 88 ff. Because of his unique personality and style, Robert Moses was an exception to the generalization that part-time officials largely yield power to full-time staff members. Moses was always the dominant force in "his" public authorities.

[16] See Melville Dalton, Men Who Manage (New York: Wiley, 1959) and Downs, Inside Bureaucracy .

an aggressive and authoritative style, even when they did not always understand substance. Moreover, when dissenters attempted to gather planning staffs with different values, whose studies might challenge highway expansion and coalition independence, the highway alliance successfully rushed funds and staff expertise into the fray.[17]

Meanwhile, spokesmen for the road coalition maintained a steady drumfire of press releases and reports during the 1950s and 1960s, urging additional construction and announcing progress toward meeting everexpanding goals. A third tube at the Lincoln Tunnel was "badly needed," the Port Authority asserted in 1952, and the agency "announced its readiness to make this great contribution" toward meeting traffic demands. "The building of roads must catch up and keep pace with the output of cars," Robert Moses proclaimed in 1964. "We are behind and shall keep losing ground unless we act fast." For New Jersey's Turnpike Authority, millions of pounds of "steel, asphalt and concrete" formed the basis for "another highly productive construction season" in 1965, but its northern section would need to be expanded to 12 lanes to alleviate traffic congestion.[18]

Throughout the nation, the highway coalition's public-relations approach, aimed at ensuring public support for its efforts (and public willingness to pay the toll fares and taxes needed to expand the highway network), was supplemented by more focused communication with organized groups in the private sector. The preferences of consumers in general were represented (and sometimes distorted) by the views of organized associations of truckers, automobile users, automobile and truck manufacturers, and others whose profits and advancement were closely linked to expansion of the arterial system. Representatives of these groups were kept informed of the coalition's assessment of road-building needs, and spokesmen for the private groups joined their government brethren in negotiations with legislators and others to ensure continued access to funds and land needed for highways and interchanges.[19]

[17] Thus a major effort in the 1950s to develop a comprehensive study of transportation in the New York region was undercut by the Port Authority in an adroit series of maneuvers, which is described in the next chapter. Ultimately, the authority provided most of the funds for the study, in return for a treaty assuring that the study commission would not attempt to develop a coordinated plan for rail and road facilities. The significance of this restriction was lost on the region's major newspapers, who greeted the announcement of the authority grant with praise for a "highly constructive turn in Port Authority thinking," and for a "courageous decision" to finance a study "that starts without preconceptions or prejudices." (Doig, "Regional Politics and 'Businesslike Efficiency,'" pp. 120–121. The quotations above are from editorials in the New York Times, January 14, 1955 and the Bergen Evening Record, January 15, 1955.)

[18] The quotations are from Port of New York Authority, Thirty-Second Annual Report: 1952 (New York: 1953), p. 6; Robert Moses, remarks to the National Highway Users Conference at their meeting in the Indonesian Pavilion at the World's Fair, New York, May 8, 1964; New Jersey Turnpike Authority, 1965 Annual Report (New Brunswick, N.J.: January 14, 1966), p. 18.

[19] See, for example, the discussion of interest groups in Robert S. Friedman, "State Politics and Highways," in Herbert Jacob and Kenneth N. Vines, eds., Politics in the American States, second edition (Boston: Little, Brown, 1971), pp. 477–519. One of the major national successes of the coalition and its private-sector allies was their campaign to require that gasoline taxes and all other funds from highway-related sources be used solely for highway projects. By the early 1960s more than half of the states had passed laws forbidding diversion of highway revenues to other uses, and the coalition and its allies won a signal victory at the national level in 1956, when the Highway Trust Fund was created and all federal highway-related taxes were reserved to that fund, to be used to aid state road-building efforts.

Bondholders were particularly important for the public authorities. They formed a distinct interest group that constrained authority officials, while at the same time enhancing their discretion. In general, the authorities did not have access to tax revenues so most of the funds to construct their bridges and turnpikes were raised by selling tax-exempt revenue bonds to individual and institutional investors, with the bonds secured by revenues from each authority's tolls and rents.[20] Thus the bondholders and their representatives were constantly watchful, to ensure against actions that might undermine the agencies' ability to repay the interest and principal on out-standing bonds. At times, the bondholders' views clashed with those of the average motorist and the organized highway lobby. For example, bondholders opposed the recurring demand that turnpike tolls be reduced or eliminated, seeing this as a hazard to authority solvency. And they were wary of proposals for authority construction of new bridges, tunnels, and turnpike extensions if there were any uncertainties as to the profitability of a new project.

Although the private highway lobby and the financial community were uneasy allies, the authorities found the bondholders quite comfortable bedfellows. To the leaders of the highway, thruway, turnpike, and port authorities, the bondholder perspective provided an essential component of their agencies' strength and their own power. Revenue bond financing provided the justification for toll roads, and without the constitutional obligation to protect bondholder interests, public pressures undoubtedly would have led to reduced toll rates. Lower tolls would soon convert the authorities from vigorous agencies seeking new projects to custodial agencies, engaged in the sweeping and painting of aging facilities. Thus the financial strength of the public authorities—and their ability to attract skilled and aggressive leadership—were crucially aided by the bond-market constraint.[21]

Moreover, revenue-bond financing was a central element in the authorities' ability to maintain an image of competence and independence. Because these agencies had to meet their expenses without recourse to the taxing power, they could be viewed as similar to private firms, requiring "businesslike efficiency" and insulation from control by elected officials to survive. This image was readily grasped by the region's press. "All too frequently," a leading New York newspaper observed, "men elected to office are not qualified to tangle with complicated modern municipal management. . . . Time after time when the politicians have gotten in a jam they have had to create an

[20] The Port Authority's use of revenue-bond financing dates from the 1920s. Its success in using this approach played a crucial role in popularizing revenue-bond funding for public projects in the United States. See Erwin W. Bard, The Port of New York Authority (New York: Columbia University Press, 1942), Chapter 8.

[21] Debt service on bonds issued by a public authority is paid from the revenues produced by its facilities. Efforts to reduce tolls and rents substantially would jeopardize the ability of the authority to meet its financial obligations to bondholders, thus raising the prospect of a legal challenge under the contract clause of the U.S. Constitution (Article I, 10:1, prohibiting any state law " . . . impairing the Obligation of Contracts . . . "). Such reductions would also make it very difficult for the authority to sell bonds in the future, unless its bonds were secured by tax revenues as well as toll receipts. See the discussion in the U.S. Supreme Court opinion in United States Trust Company v. State of New Jersey, 431 U.S. 1 (April 27, 1977).

authority and call on successful businessmen to bail them out."[22] Public officials also heaped praise on these agencies, with special compliments directed toward the Port Authority. "Through its great public works," exclaimed New York Governor Thomas E. Dewey in the 1950s, the Port Authority "has set an example for the administration of public business on a sound and efficient basis."[23]

These encomiums to the Port Authority and to public authorities generally were not simply "natural events." They were cultivated by the authorities' leaders to stimulate public support for their efforts to meet transportation needs, and to enhance their ability to determine the pace and location of major arterial projects. In speeches, press releases, and reports—on every possible occasion—spokesmen for Triborough, the Port Authority, and their brethren emphasized that their efforts, "financed by prudent investors," were essential to the region's expansion. These are "immensely productive, independent ad hoc agencies," argued Triborough chairman Moses, which "represent government in business and accomplish what theorists promise and do not perform."[24] They place revenue-producing facilities "on their own feet and on their own responsibility," commented another authority spokesman, and "free them from political interference, bureaucracy and red tape. . . . "[25] That these themes were reflected in the assessments by governors and legislators, and in the "1400 favorable editorials in the New York and New Jersey press," should not be surprising, for the authorities and their associates in the highway coalition were engaged in an immensely successful campaign of public education.[26]

The authorities' themes of independence and prudent financing were emphasized and then extended to include "cooperative planning" among all highway agencies, and the "urgent necessity" to build more roads in order to

[22] "Government by Authority," editorial, New York World Telegram and Sun, March 12, 1952. Similarly, the Newark Evening News commented editorially that the Port Authority "continues to confound those who deny that government can engage in economic activity with imagination, boldness, efficiency and profit" ("Success Story," editorial, April 20, 1959). Ironically, the search for profit eluded both of these newspapers, and they succumbed to bankruptcy some years ago.

[23] Dewey's statement is reprinted in Port of New York Authority, Thirty-Second Annual Report: 1952 (New York: 1953), frontispiece; cf. the highly favorable comments by New Jersey's Governor Alfred E. Driscoll in the same report, and by later Governor Richard J. Hughes of New Jersey, quoted in Clive Lawrence, "Port of New York Authority: A Towering National Presence," Christian Science Monitor, June 9, 1971. See also New Jersey Senate, Special Senate Investigating Committee (under Senate Res. No. 7 of 1961), Report (Trenton: June 28, 1963), which describes the Port Authority as a "vital organization" through which the two states have "procured vast public improvements without charge to the general taxpayers" and notes that this agency, "like many other public authorities . . . is expected to operate on business principles." Substantial portions of the Senate committee report are reprinted in Port of New York Authority, Annual Report 1963 (New York: 1964), pp. 64–75; the quotations above are on pp. 64, 69.

[24] Robert Moses, remarks to the National Highway Users Conference at their meeting in the Indonesian Pavilion at the World's Fair, New York, May 8, 1964. For a compilation of his other public statements, see his Public Works: A Dangerous Trade (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1970).

[25] Austin J. Tobin, executive director of the Port Authority, in "The Work and Program of the Port of New York Authority," February 10, 1953. Cf. other addresses by Tobin: "The Authority Method of Handling Large Projects," May 19, 1955; "Address of Acceptance of the Annual Award of the Henry Laurence Gantt Medal," September 25, 1962. Tobin joined the Port Authority staff in 1927, and served as its chief full-time official from 1942 until December 1971.

[26] The quotation is from Austin J. Tobin, "Public Relations and Financial Reporting in a Municipal Corporation," May 23, 1951. The tally of 1,400 covered the period 1945–1951.

"catch up and keep pace with the output of cars."[27] Contrary themes—the possible need for coordination of rail and road planning, or a concern for community disruption as new highways cut through villages and cities—were heard only sporadically through the 1960s. Instead, the highway builders responded to one important set of public concerns, and strongly influenced the way transportation problems were defined by elected leaders and in the press, thereby shaping the kinds of solutions that seemed desirable in the public mind. It was surely a performance worthy of the Silver Anvil award of the American Public Relations Association.[28]

The highway coalition was not, of course, all powerful. While some observers, such as Robert Caro, have characterized Moses and his coalition colleagues as the prime initiators of suburban sprawl and rail service decline in the New York region, neither Moses nor the highway alliance as a whole had that strong an influence.[29] Individually and collectively, however, they did help to shape the values and expectations of the region's opinion leaders and citizens, building on a growing interest in mobility and suburbanization, and focusing that interest on projects and programs of immense scope and—from some perspectives—immense benefit.

Even in their early years, the individual members of the alliance were able to plan and act using a canvas far larger in regional terms than that available to even the largest cities or to the counties. As a highway builder, Moses could range across New York City and far east into Long Island. The Port Authority crossed state lines, with a jurisdiction that included more than 350 municipalities in a dozen counties, in addition to New York City. While the state highway departments and turnpike authorities took a more partial view of the region, their geographic scope was, of course, wide-ranging. In the 1950s, cooperative efforts among these agencies increased substantially, enhancing their ability to influence the location and timing of projects, and to tip the scale toward public approbation of large programs.[30]

[27] The quotations are drawn from the Port Authority and Triborough Authority, Joint Study of Arterial Facilities, 1955, pp. 6–7, and from Moses's Remarks, May 8, 1964.

[28] This was one of several awards received by the Port Authority's director of public relations during the 1950s and 1960s.

[29] In his monumental study of Robert Moses and New York City, Caro argues: "By building his highways, Moses flooded the city with cars. By systematically starving the subways and the commuter railroads, he swelled that flood to city-destroying dimensions. By making sure that the vast suburbs, rural and empty when he came to power, were filled on a sprawling, low-density development pattern relying primarily on roads instead of mass transportation, he insured that that flood would continue for generations if not centuries. . . . " As to the public authority, Caro observes that it "became the force through which he shaped New York and its suburbs in the image he personally conceived." Robert A. Caro, The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York (New York: Knopf, 1974), pp. 15, 19. The similarities in development patterns between the New York area and other metropolitan regions immediately cast doubt on Caro's interpretation that saw Moses individually as the cause of what happened in New York.

[30] The interconnections between greater cooperation and magnified influence worked in several ways. For example, the augmented flow of toll revenues gave authority leaders an incentive to envision larger and more expensive programs for their individual agencies; but in the transport field such efforts would almost inevitably require collaboration with other agencies across city and state lines. Similarly, the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956 provided millions of dollars of additional federal funding for use by state highway departments, encouraging their officials to think more expansively—and more cooperatively—as well. The important role of federal officials, in the Bureau of Public Roads, in allocating these funds also encouraged cooperation across state lines. Cooperative efforts and larger influence were also aided by rotation and overlapping appointmentsof officials; for example, Charles H. Sells was superintendent of New York State's highway agency (titled Department of Public Works) before becoming a commissioner of the Port Authority in 1949; and S. Sloan Colt, long-time commissioner of the port agency, was a member of the President's advisory committee that recommended the expanded federal highway program enacted in 1956.

The independent authority structure, and the motivations of its leaders, were crucial to the timing of development in the New York region. Without these agencies, the pace of highway development and suburban expansion would undoubtedly have been slower; and perhaps some of the most significant projects, such as the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge, would not yet have been constructed. In other urban regions, the leadership of the highway coalition was centered in state highway departments and other executive agencies. But in New York, the large obstacles of waterways and state lines made the authorities a very useful and perhaps essential component in meeting regional "needs," thus adding an important ingredient to the organizational imperatives which shaped highway-coalition strategies.

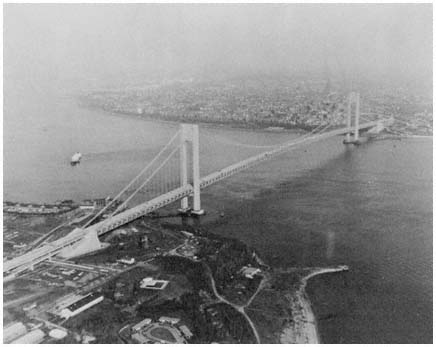

Even in the heyday of road building, however, public support often could not simply be taken for granted. It was a prize for skillful effort that at times eluded even the best of the highway-planning strategists. Illustrative of the patterns of cooperation in the alliance, and the sometimes uncertain linkage to public approval, are the arterial highway studies undertaken during the 1950s. In 1954, the Port Authority and Moses, working closely with other members of the highway coalition, carried out a major study of the region's traffic patterns, and recommended a number of "needed" improvements. Included in their proposals were a lower deck on the George Washington Bridge across the Hudson River, a six-lane Throgs Neck Bridge between The Bronx and Queens, a twelve-lane bridge across Upper New York Bay between Brooklyn and Staten Island at the Narrows, a new bus terminal near the George Washington Bridge, and dozens of miles of connecting highways and expressways in New Jersey and in the five boroughs of New York City. The Port Authority and Triborough were prepared to allocate nearly $400 million to construction of the major toll crossings and immediate approaches, while about $200 million in state and federal funds would be needed to complete the toll-free connecting highways. In addition, another $150 million would be required if two cross-Manhattan expressways were to be built, as the report recommended.[31]

In terms of the potential impact on regional growth patterns, the single most important project was the Narrows Bridge, which would extend across a mile of water at a cost of $220 million, and provide the first direct connection between Staten Island and the other boroughs of New York City, as well as permitting direct automobile and truck traffic from Staten Island to Long Island.[32] Construction of that bridge had long been an important goal for Moses, but he estimated that Triborough revenues from other toll facilities would not be sufficient to underwrite construction of the Narrows span until the mid-1960s. After extensive negotiations, the two agencies announced in

[31] Port Authority and Triborough Authority, Joint Study, 1955, 62 pages.

[32] Before the Narrows Bridge was completed, Staten Island's vehicular traffic could journey to the rest of New York City either by embarking on the Staten Island ferry, which deposited travelers at the lower end of Manhattan, by using smaller ferries which connected with Brooklyn, or by crossing by bridge to New Jersey, then traveling north and crossing the Hudson via bridge or tunnel, finally arriving in Manhattan.

January 1955 that the Port Authority would finance and construct the Narrows Bridge, thus permitting its completion a decade earlier than would otherwise be possible, and encouraging rapid population growth in this "last large undeveloped area adjacent to Manhattan." Triborough would operate and maintain the bridge and some years later, when its credit position permitted, would purchase the Narrows Bridge from its wealthier partner.[33]

In order to carry out the massive program, the highway alliance would have to obtain large amounts of state and federal funding. To win political support in New Jersey, the Port Authority agreed to tap its own bountiful reserves in order to pay for the state's share of the $60 million in federal/state funds required for the new arterial highway that would cross Northern Jersey to the George Washington Bridge.[34] But larger amounts would be needed for the expressways on the New York side, and voter approval of a transportation bond issue would be essential. Members of the state's highway department and the authorities developed a $750 million proposal that would provide funds for highway improvements throughout New York State, submitting it for voter approval in 1955. To enhance prospects for support of the bond issue, New York City's construction coordinator, the ubiquitous Robert Moses, wearing one of his many hats, agreed to open two nearly completed expressways a few days before the referendum—thus providing a dramatic opportunity to emphasize the public benefits that could flow from expanded highway-building funds.

Unhappily for highway forces, the public whose needs were being served found the price tag too high, and the bond issue went down to defeat in November 1955. The coalition then regrouped, pared the total sum down by one third, to $500 million, mounted a vigorous campaign to dramatize the necessity for an ever-expanding highway system, and won approval at a bond referendum in 1956.

The Highway Coalition at Work

The interplay between public demand, the strategies and motivations of government officials, and other factors that shape transportation patterns—and through transportation patterns alter the distribution of population and jobs—are inevitably complex in a large and variegated metropolis. In the remainder of this chapter, we give three cases closer scrutiny to show this interplay in more detail. The first case describes the steps leading to construction of the Holland Tunnel and the George Washington Bridge. Here we see the limitations of relying on the private sector for the development of large transportation projects. Also underscored is the importance of organizational motivations and strategies in encouraging and crystallizing "public demand" for highways, and in shifting regional priorities from rail projects toward a road-building program. Moreover, in the Port Authority's successful effort to

[33] Ibid., pp. 7, 21, 30. In fact, Triborough revenues built up more rapidly than expected, and the agency assumed full responsibility for constructing and financing the Narrows Bridge at the end of 1959.

[34] Ibid., p. 38.

absorb a rival agency—to ensure that there would be no competition in tolls among trans-Hudson facilities, and that the "profits" would be at the disposal of the Port Authority—we see the importance of strategic skill in laying the groundwork for the authorities' later capacity to engage in regional development works.

A second case focuses on construction of the Manhattan Bus Terminal, and illustrates the importance of planning and political capabilities in carrying out a significant project in the face of opposition from the private sector and governmental rivals. In the third case, we look more closely at the motivation and results of the major project resulting from the highway coalition's studies of the 1950s, the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge.

Under and Over the Hudson River

Demands for vehicular routes that would overcome the Hudson barrier to regional commerce and travel began long before 1900. The initial efforts failed because of differences in perspective and priorities between the states, and because of a desire to rely on private enterprise.

As early as 1868, New Jersey chartered a private company to construct a bridge across the Hudson, but concurrent authority was not obtained from New York State until 1894; the company made no progress and finally lost its charter in 1906 for nonpayment of taxes. In 1890, a second group obtained a federal charter for a private toll bridge, but could not raise money to begin construction. In 1917, the Public Service Corporation of New Jersey studied the possibility of a tunnel under the river but decided against it because of high costs.

As Erwin Bard notes, "private enterprise struggled for a long period with the problem of providing interstate crossings" for motor vehicle traffic.[35] Meanwhile, vehicular passengers and freight were compelled to use ferries and barges to cross the Hudson. Their slow journeys contrasted sharply with travel between New Jersey and New York City by rail tunnels after 1910. The completion of these tunnels under the river permitted the Pennsylvania Railroad and the Hudson and Manhattan rail company to bring their passengers from New Jersey directly into Manhattan terminals.

In the period between the two world wars, three major vehicular crossings were completed: the Holland Tunnel in 1927 and the George Washington Bridge in 1931, followed by the Lincoln Tunnel, which began operation at the end of 1937. Among the reasons for this sudden surge, with its considerable impact on the region's patterns of population growth and commerce, were the sharp rise in motor transportation during the 1920s, coupled with appeals from Bronx and Manhattan business groups, who favored the crossings as a way to reduce ferry congestion on the river and to improve business by reducing transportation time for customers west of the Hudson. Perhaps even more significant was the creation of new government organizations to overcome the interstate hiatus, together with the allocation of public funds for their construction activities, and the skillful efforts of these new agencies to enhance their power.

[35] Bard, The Port of New York Authority, p. 192. The factual data in this section are drawn mainly from Bard's definitive study.

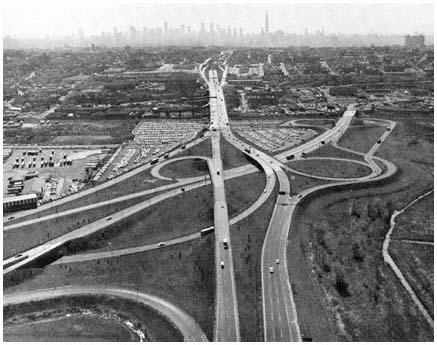

The roads linking the New Jersey Turnpike and the Lincoln

Tunnel in Hudson County were built through

cooperative efforts of three major components

of the highway coalition—the Port Authority,

the New Jersey Turnpike Authority, and the New Jersey Highway Department.

Credit: Port Authority of New York and New Jersey

After the early private efforts failed, the two states created commissions in 1906 to study ways of spanning the Hudson. Intermittent cooperation and several sporadic reports followed. The commissions suggested a tunnel under the river between lower Manhattan and Jersey City, but were unable to agree on how it would be financed or administered. "After years of groping and fumbling," the two states finally agreed in 1919 to establish independent state commissions to function in unison (it was hoped) and construct the proposed tunnel. The cost of the tunnel would be financed by tolls. Conflicts between the two commissions were frequent during the next several years, and cost overruns required additional state aid, but the Holland Tunnel finally opened in November 1927.[36]

Meanwhile, the Port of New York Authority had been established in 1921 as a joint agency of New York State and New Jersey. The authority was given broad responsibility for solving transportation problems in the region, but the main motivation for its creation was the widespread desire to improve the handling of rail freight. The agency's officials soon entered into complex

[36] Ibid., pp, 178–183; the quoted phrase is on p, 180. The original estimated completion date had been 1923.

negotiations with the railroads aimed at devising a more efficient system of consolidated freight yards and related facilities throughout the region.

At the same time, business and civic groups urged both states to approve additional vehicular crossings for the Hudson River. Neither governor was pleased with the performance of the dual commissions, and both agreed in 1923 that future bridges and tunnels should be "constructed and financed by the Port Authority." Initially, the authority showed little interest in turning to vehicular projects, as its negotiations with the railroads "seemed on the verge of important accomplishments." But when these discussions foundered, Port Authority officials began to look actively for an alternative program. As Erwin Bard, historian of the authority's development, commented:

Within the Port Authority the center of gravity began shifting to vehicular traffic. . . . The "do-something" policy in terms of construction was rising. It was imperative that the Port Authority's credit, hitherto entirely theoretical, be established. The bridge-building program offered a chance.[37]

The major project under consideration at this time was a bridge across the Hudson between upper Manhattan (about 178th Street) and Fort Lee, in Bergen County. A bridge in this location was favored by business and civic interests in Manhattan, and the proposal was pressed actively in the early 1920s by government officials and civic leaders in Bergen, who saw the bridge as a key factor in Bergen County's ability to attract the new wave of suburbanites. Among the leading New Jersey supporters of the project were the editors of the Bergen Record (whose economic strength and influence would grow with an expanding population) and state senator William B. Mackay (who hoped that leadership in meeting public concern for improved transportation facilities would advance his gubernatorial aspirations), as well as other civic leaders and government officials in the county.[38] Thus the campaign for the bridge illustrated the interrelationship between public demand, the interests of civic and business leaders, and strategic aims of public officials. Among the government units centrally involved was the Port Authority, whose leaders were actively seeking a path to success. They found it through undertaking the bridge project, and then used that effort to eliminate a rival organization and to establish a long-range financial strategy for institutional growth and power.

The Port Authority's leaders did not believe they could move publicly and decisively to harness the support which the 178th Street bridge commanded. For the proposal attracted opponents as well as enthusiasts. Some

[37] Ibid., pp. 182, 185.

[38] The most active civic group in the New Jersey campaign for the bridge was first named the Mackay Hudson River Bridge Association. The efforts of Mackay, the Record, local officials, and others are recounted in Jacob W. Binder, All in a Lifetime (Hackensack, N.J.: published privately, 1942; available in New Jersey libraries), pp. 181–198. Binder served as executive director of the Bridge Association. On the campaign for a bridge at 178th Street, see also "For Hudson Bridge Above 125th Street," New York Times, December 28, 1923; "Chamber Opposes Bridge at 57th Street," New York Times, January 4, 1924; "Greene Tells Plan for Hudson Bridge," New York Times, May 4, 1924; "Bridge Across Hudson at 178th Street is Discussed at Interstate Conference," New York Times, January 21, 1925; "Approves Hudson Bridge," New York Times, February 3, 1925; "Diners Hail Mackay as Father of Bridge," New York Times, April 23, 1925.

business and civic groups strongly favored a rival plan for a combined railroad-vehicular bridge, perhaps to be built by a private corporation, at 57th Street in Manhattan. Several conservation groups objected to the loss of park land that would occur if the bridge were built in the vicinity of 178th Street. Regional jealousy reared its expected head, when spokesmen for Queens criticized the project as catering to New Jersey's interests while the city's transportation needs were neglected. And some legislators in Trenton argued against expanding the Port Authority's role to include highway bridges.[39]

Amid these conflicts, the Port Authority moved cautiously. After a series of hearings in 1923, it concluded that a vehicular bridge should be built "north of 125th Street." As sentiment in favor of a span at 178th Street crystallized during the next year, the authority's chairman called such a crossing a "great necessity," and circumspectly announced in December 1924 that the authority was "ready to perform whatever tasks are designated to it" by the two states.[40] But when the authority was attacked as an advocate of the bridge proposal, its officials explained that the Port Authority had only concluded that "perhaps a bridge at some point" north of 125th Street was needed.[41]

Out of the public eye, however, Port Authority lawyers and engineers worked closely with both governors and with citizen groups who favored the bridge, as they pressed for legislative approval. Finally, in the spring of 1925, both states enacted legislation authorizing the Port Authority to construct the Hudson River bridge.[42]

Two years later, the Port Authority could speak about the project more expansively. The bridge across the Hudson, the agency declared, "means that the dream of many years and of many millions of persons will finally be realized." The "agitation" for such a bridge "took on the form of a public demand from the populations on both sides of the stream," the authority explained, "until the demand could be no longer logically be resisted."[43] Construction was begun at the 178th Street site in 1927, and the George Washington Bridge was opened to traffic in 1931, ahead of schedule and at a cost below the original estimate.

If Port Authority officials wished to satisfy their newly developed interest in motor transport, however, it seemed imperative that the revenue-

[39] The opponents' views are set forth in "Sees Need for Five New Hudson Tubes," New York Times, December 6, 1923; "Chamber Opposes Bridge at 57th Street," New York Times, January 4, 1924; "Insist on 57th Street Bridge," New York Times, January 6, 1924; "Ferries, Bridges and Tunnels," editorial, New York Times, January 15, 1924; "Hudson Bridge Bill Passed," New York Times, February 10, 1925; "Committee Favors 57th Street Bridge," New York Times, February 28, 1925; "Move to Save Park at Fort Washington," New York Times, March 18, 1925; "Fear Effects of Bridge," New York Times, March 28, 1925.

[40] Port of New York Authority, "Report to the Governors," December 21, 1923, reprinted in Port Authority, Third Annual Report: 1923 (New York: February 1, 1924), pp. 43–50; Julian Gregory, chairman of the Port Authority, quoted in "Explains Bridge Plan," New York Times, December 30, 1924.

[41] W. W. Drinker, Chief Engineer of the Port Authority, quoted in "Move to Save Park at Ft. Washington," New York Times, March 18, 1925.

[42] Laws of New Jersey, 1925, c. 41; Laws of New York, 1925, c. 211. In 1924–26, the authority was also authorized to build three smaller vehicular bridges between Staten Island and New Jersey.

[43] Port of New York Authority, 1926 Annual Report (New York: January 20, 1927), pp. 55–56.

producing Holland Tunnel be acquired. For the Holland Tunnel, opened by the dual commissions in the fall of 1927, proved an immediate success. High traffic volumes and substantial revenues generated enthusiasm within the two commissions for more projects, and in 1928 they recommended to both states that they be authorized to construct a tunnel to midtown Manhattan immediately, and three other crossings thereafter. Meanwhile, sagging toll revenues on the Port Authority's facilities raised doubts as to the ability of the authority to meet its financial obligations.[44]

At this point, the Port Authority exhibited the tactical skill that would become a hallmark of its operations. In private discussions and public debate, it argued for the following approach to regional transport development:

1. Interstate rail and highway projects should not be considered separately, but instead as part of one comprehensive transportation plan. (Since the Port Authority already had rail responsibilities and the dual commissions did not, this principle would support vehicular expansion by the authority and cast doubt on the legitimacy of the commissions' efforts.)

2. All interstate motor vehicle crossings should be financed by revenue bonds, not by using the credit of the states. (The authority was authorized to issue revenue bonds, while the commissions used state funds to be repaid out of toll revenues.)

3. To ensure that revenue bonds could be sold to investors, all interstate bridges and tunnels should be under the control of one agency. Otherwise, tolls on one facility (for example, the Holland Tunnel) might be reduced below that of other facilities, and this "unfair competition" would drain off traffic and revenue from the other crossings.

4. As a further aid to revenue-bond financing, income from all projects should be pooled, so that "excess returns from the more profitable enterprises" could support weaker or new facilities.

The authority put forth two other arguments that would not reappear in its later reports and announcements. "It is perfectly obvious," the authority declared, that the general level of tolls "could be placed on a much lower basis" if all facilities were under one management rather than under divided authority. Also, the revenues pooled in the general fund would be devoted to paying off the debt on the interstate crossings, "with a view to making these facilities free from tolls within the least possible time."[45] In fact, the general level of tolls remained at fifty cents until 1975 when it was raised to seventyfive cents.

At a series of meetings in 1930 and 1931, officials of both states finally accepted the Port Authority's arguments, the dual commissions were abolished, and the Holland Tunnel was transferred to the authority. Moreover, the states agreed that future interstate crossings would be developed by the

[44] The Port Authority opened two of its Staten Island bridges in 1928. In 1929 and 1930 revenues from these bridges were far below original estimates, and the first series of bonds seemed likely to face a default. See Bard, The Port of New York Authority, pp. 237–238.

[45] See Port of New York Authority, Eighth Annual Report (New York: December 31, 1928), pp. 59–61; and Port of New York Authority, 1929 Annual Report (New York: December 31, 1929), pp. 51–52.

authority, under the four principles summarized above. Perhaps understating the importance of the Port Authority's deft maneuvers, Bard concludes that the authority's "reputation for efficiency, its autonomous power to finance, and its established credit won in the race for survival."[46]

Through its activities and successes during these early years, the Port Authority established an approach to governmental action that would be repeated again and again in the New York area, as well as in other parts of the country. First, it set a precedent for financing highway facilities by revenue bonds, supported by tolls. This strategy obviated the need for state legislatures to appropriate moneys for such facilities out of general funds, or to approve the issuance of bonds backed by the full faith and credit of the state. Thus, the speed with which self-supporting bridges, tunnels, and turnpikes were constructed during the next four decades was greatly increased. The availability of revenue-bond financing also encouraged state officials to create additional public authorities as a way of avoiding direct responsibility for additional taxes.[47]

A second precedent, that each facility would be supported by the pooled revenues of all other authority projects, shaped the development of later public authorities in the transportation and port development fields.[48] It also had a decided impact on the evolution of the Port Authority itself. The pooling concept provided the rationale and financial base for extensive authority activity in airport, harbor and rail development. Otherwise, the agency would have been limited to those very few projects whose "self-supporting" nature was so evident from the outset that cautious investors would buy bonds without broader security. The pooling concept permitted the Port Authority to insulate individual projects from the short-run (and in some cases even the long-run) impact of market forces. Surpluses from bridges and tunnels could be used to underwrite new enterprises that might incur initial or continuing deficits, if those new projects seemed desirable in terms of overall regional development—or, at times, if they seemed beneficial in terms of the financial strength and public image of the authority and its officials.

[46] Bard, The Port of New York Authority, p. 191. In 1931, the Port Authority was authorized to proceed with the midtown Lincoln Tunnel. Strictly speaking, the dual commissions were not abolished, but merged with the PNYA, which absorbed some of the commissions' staffs.

[47] For example, the New Jersey Turnpike Authority was created in 1948 partly as a way to overcome the reluctance of the New Jersey legislature to provide substantial sums for highway building in the early postwar years.

Members of the dual state commissions and other critics of the authority concept argued that it would be less expensive, and therefore better, to finance new road facilities with state advances, to be repaid through toll receipts. This approach was used for the Holland Tunnel, and it probably would have been less costly for the later bridges, tunnels, and toll roads to have been financed in this manner, since interest rates on state-backed loans would have been lower than interest on bonds backed mainly by an authority's projected toll revenues. The political disadvantages of state appropriations, however, combined with the mixed administrative record of the dual commissions, were more persuasive at the time. See Bard, The Port of New York Authority, pp. 180 ff.

[48] On the influence of the Port Authority's structure and early evolution on the development of other public authorities, see Council of State Governments, Public Authorities in the States (Chicago: 1953), p. 23; State of New York, Temporary State Commission on Coordination of State Activities, Staff Report on Public Authorities under New York State (Albany: 1956), p. 15; and Richard Leach and Redding S. Sugg, Jr., The Administration of Interstate Compacts (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1959), p. 8.

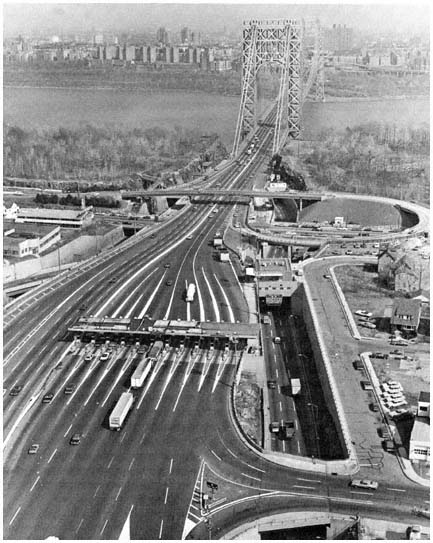

The George Washington Bridge,

looking east across the Hudson River at upper Manhattan with

the Port Authority's toll plazas in the foreground.

Credit: Port Authority of New York and New Jersey

The Port Authority had spanned the Hudson River, and the new George Washington Bridge soon proved a major revenue producer for the authority. Along with the Holland Tunnel it provided the financial base for constructing the midtown Lincoln Tunnel in the 1930s, and for entering a wide range of other activities a decade later. The bridge also proved a valuable resource in maintaining the image of the Port Authority as an efficient and important regional enterprise. Opened with great ceremony in the fall of 1931, the

George Washington Bridge was widely praised for its design and construction—it was the longest suspension bridge in the world—and because of its impact on Bergen County. During the next two decades, the authority was frequently commended for inaugurating "a new era in bridge building" with this majestic span, and the bridge was called the "greatest single factor in Bergen County's growth."[49]

The new bridge did indeed have a significant impact on development west of the Hudson. Previously, rail lines and ferries provided only circuitous, time-consuming access to Bergen, and the sprawling county had remained a semirural enclave while nearby counties with better access to Manhattan urbanized rapidly before World War I.[50] Once the two states had approved the bridge in 1925, real estate speculators packed the county office building in anticipation of the land boom.[51] The next thirty years saw a tripling of Bergen County's largely middle-class population, many of the new residents having departed from the Bronx and other parts of the core to "reside in the pleasant environment of Bergen County."[52]

Property values also climbed rapidly. Between 1920 and 1954, assessed values increased by more than 250 percent in Bergen, compared with about 100 percent in Essex County and in the Garden State as a whole during this period. And the decision to span the Hudson at 178th Street, rather than at 125th Street or 57th Street (the latter across from Hudson County), altered the attractiveness of land and the pattern of growth within the county. Changes in property values among Bergen's towns illustrate the impact of the bridge: municipalities nearest the span saw their taxable property increase especially sharply, rising from three to ten times the 1920 values.[53]

For Port Authority strategists who recognized favorable publicity as a route to enhanced power, the George Washington Bridge and its impact gener-

[49] The quotations are, respectively, from "Development of New York Port Lesson in States Co-operation," Christian Science Monitor, May 5, 1946, and "The Birth of a Bridge," editorial, Bergen Evening Record, April 30, 1946.

[50] Much of Bergen County was as close to the Manhattan CBD as the Bronx and southern Westchester County, which were served by direct rail service and a growing highway network, and no more distant than Essex and Union counties in New Jersey, which had direct rail service to Manhattan. Travelers from Bergen County who did not wish to swim the Hudson reached Manhattan by journeying south via rail or road into Hudson County, where they could cross by the Weehawken ferry, or (going farther south) via the Hudson and Manhattan rail system (now PATH).

[51] "The proposed bridge over the Hudson River," reported the New York Times in December 1925, "has so stirred up real estate activities in Bergen County that the searcher's room in the new $1 million court house at Hackensack is wholly inadequate. Today petitions were circulated asking the Freeholders to provide more room for the lawyers' clerks and searchers." ("Bridge Talk Stirs Bergen County," New York Times, December 4, 1925.)