19—

RIPARIAN INITIATIVES AT THE LOCAL LEVEL

IS A STATE MANDATE NECESSARY?

A State Mandate for Riparian Wetland System Preservation[1]

Bruce E. Jones[2]

Abstract.—Management of aquatic and riparian wetlands and floodplain resources generally, is fragmented, uneven, and often contradictory. State programs are reviewed and a sample local ordinance is presented. A California Floodplain Management Act is proposed.

Introduction

The panel on politics, legislation, and management programs is the most important topic of the California Riparian Systems Conference. Ecology, of course, makes the world go around, but it is politics—and its spawn, legislation—that either saves it or loses it. I will briefly review the highlights of a two-year research project prepared for three state agencies and a book in preparation[3] which includes a critique of federal, state, and local government programs and laws affecting riparian and other wetland resources. Then, based on the insight gained by this study, I will propose state legislation I believe is necessary to create a workable management program in California.

At the federal level, substantial attention has been given to wetlands through the Section 10/404 permit program of the US Army Corps of Engineers (CE) and Presidential Executive Orders 11988 and 11990 of 1977 (floodplain and wetland protection). California has some useful legislative and administrative policies for the more aquatic wetlands, but, except for the Coastal Act,[4] there are no implementable regulations for either aquatic or riparian wetlands and stream systems. At the local government level, it is fairly common to find general plan policies addressing wetlands and even riparian vegetation, usually in brief references, and, interestingly, there are more ordinances for streamside management than for aquatic wetlands. But again, coverage is uneven.

The overall picture is one of a jigsaw puzzle with a few pieces in place but with large gaps throughout.

Overview of California Agencies

California does not have anything approaching a watershed resources management program; we do not have comprehensive standards for uses affecting wetlands, riparian zones, hardwood trees (oaks and riparian trees), soil erosion, and floodplain zoning. The Coastal Act provides the only thorough treatment of wetlands/stream/riparian vegetation protection, but the "coastal zone" itself severs many watersheds, which limits thorough treatment. The California Wetlands Preservation Act of 1976[5] provides some state policies, but offers no implementation procedures and penalties. A state executive order on floodplain management (1977) is poorly written and does not mention wetlands or riparian resources. Very briefly, some findings regarding the key agencies (out of over 30 reviewed) are as follows.

Bay Conservation and Development Commission

The Bay Conservation and Development Commission (BCDC), the first coastal management agency in the nation, has been effective in regulating fill intrusions into San Francisco Bay and securing mitigation, often involving restoration of tidal action to diked areas. However, there are important bay wetlands and riparian systems outside of the agency's jurisdiction.

California Coastal Commission

The best wetland and stream policies in any federal or state law are found in the Coastal Act of 1976, especially PRC Section 30231 as follows:

[1] Paper presented at the California Riparian Systems Conference. [University of California, Davis, September 17–19, 1981].

[2] Bruce E. Jones is Environmental Consultant, Environmental Projects, Sacramento, Calif.

[3] Jones, Bruce E., and Anne Sands. California marsh and stream conservation zones.

[4] Public Resource Code (PRC) Section 30000–30900.

[5] PRC Section 5810–5818.

The biological productivity and the quality of coastal waters, streams, wetlands, estuaries, and lakes . . . shall be maintained and where feasible, enhanced through, among other means, minimizing adverse effects of waste water discharges and entrainment, controlling runoff, preventing depletion of ground water supplies and substantial interference with surface waterflow, encouraging waste water reclamation, maintaining natural vegetation buffer areas that protect riparian habitats, and minimizing alteration of natural streams.

Of particular interest is the Commission's document "Interpretive Guidelines for Wetlands and Other Wet Environmentally Sensitive Habitat Areas" (California Coastal Commission 1981). While this is a very useful tool which has improved management of these resources, it is lacking in the important issue of controlling adjacent developments and setting "buffer" zones. Too much emphasis has been put on establishing a 100-ft. nondevelopable buffer, and too little guidance is given on the design and siting of adjacent construction to minimize adverse impacts. The width of a buffer is not the key consideration. Buffers not only will often be compromised for political and economic reasons, but should be, if the design of the use makes it compatible with the adjacent wetland or stream zone. Having missed this key point, the commission's guidelines leave coastal wetlands and streams vulnerable to problems from future encroachments.

California Conservation Corps

A great untapped opportunity exists for applying the skill and energy of the California Conservation Corps (CCC) to an annually scheduled program of wetland and riparian zone restoration.

California Energy Commission

Interestingly, the California Energy Commission (CEC) has some of the best state policies regarding sensitive resource areas. Its organic law and regulations recognize the constraints of the Coastal Commission and BCDC. For the rest of the state, the key provision is PRC Section 25527, which provides protections (against the siting of energy facilities) for parks, reserves, "areas for wildlife protection, recreation, historic preservation, or natural preservation," and undeveloped estuaries. In addition, the commission "shall give the greatest consideration to the need for protecting areas of critical environmental concern."

California Department of Conservation

This agency could be one of the most useful in communicating the values of aquatic and riparian wetlands, but has not yet met this potential. In its useful (but never officially released) "California Soils: An Assessment" (California Department of Conservation 1979), the department ranks streambed erosion as the third most severe of eleven soil problems in the state, but fails to advocate retention of riparian vegetation as a protective measure. Nor does the otherwise excellent "Erosion and Sediment Control Handbook" (Animoto 1978) offer anything more than: "Vegetative lining reduces the erosion along the channels and provides for the filtration of sediment . . . and improves wildlife habitat."

California Department of Fish and Game

The work of the California Department of Fish and Game (DFG) is, of course, oriented toward saving both aquatic and riparian wetlands, but it has precious few tools to do so. Studies in both areas are on-going. Of special note is the DFG authority in Sections 1601–1606 of the California Fish and Game Code to execute Streambed Alteration Agreements for any activity that will divert, obstruct, or change the natural flow or bed of a river, stream, or lake. This is a nearly unique negotiation and mediation process in the nation, but its application to riparian vegetation is limited to what DFG personnel can achieve through negotiation in specific situations.

The DFG has not initiated a vigorous program to solicit land donations of riparian corridors. Nor has it sought to develop a program of restoration of riparian vegetation on public lands. These are two of the most basic elements of any start-up state riparian resources program.

California Department of Forestry

The California Department of Forestry (DF) timber harvesting program is almost exclusively oriented towards conifers. It has reported that only one percent of commercial harvesting is of broad-leafed or hardwood species. However, this figure is misleading because the true amount of cutting of these species cannot be determined since it is not regulated. They are in fact being overharvested and any percentage is immaterial; regulation is needed, either by adoption of administrative rules under the Forest Practices Act of 1973[6] or amendments to it. The DF position is that the act, as it is now written, cannot be used to regulate riparian species. Therefore, amendments to the act should be sought by DF.

California Department of Health

Regulations by this department illustrate the competing interests that must be considered in riparian vegetation management. Thickets of streamside growth, especially blackberry tangles, in urban areas can harbor rats. The department is especially concerned with wetlands restoration and has several sets of guidelines for minimizing mosquitoes.

[6] PRC Section 4511–4628.

California Department of Parks and Recreation

The California Department of Parks and Recreation (DPR) should develop policies that will classify its wetlands and riparian corridors as "natural preserves" (except those wetlands used for duck hunting), which would prevent intrusions of parking lots, campgrounds, and other intensive uses.

California Department of Water Resources

The California Department of Water Resources (DWR) has in recent years increased its documentation and policy support for preservation of riparian vegetation and instream retention of water (see "Policies and Goals for California Water Management for the Next 20 Years" [California Department of Water Resources 1982]). These policies do not always reach down to the day-to-day operations of DWR. Specifically, the management of DWR's own Maintenance Areas, which include some 300 mi. of waterways, should be redefined to require more sophisticated, selective treatments, including integrated pest management techniques, where possible.

DWR is further constrained by restrictive standards required by CE for so-called "project levees" (where federal funds have been used). There is wide opinion, even within DWR, that these levees can safely retain more vegetation than CE policy currently allows.

Office of Planning and Research

The Office of Planning and Research (OPR) has failed to recognize the existence of wetlands and riparian resources within city limits in its "Urban Strategy Report" (Office of Planning and Research 1978), a situation especially unfortunate since the report is backed up by an executive order to state agencies to implement it. Even more worrisome is the superficial treatment of wildlife habitat preservation in general in the OPR "General Plan Guidelines" (Office of Planning and Research 1980). Detailed appendices for this document should be prepared with DFG to assist local planners in the technicalities of preserving habitat.

The Resources Agency

In September 1977 then-Secretary Huey Johnson released a most useful internal policy on wetlands preservation (amended in July 1980), but no effort has been made to strengthen it through incorporation into an executive order or legislation. Nor has, there been equal attention to development of a riparian policy for the agency. The document, for the excellent renewable resources program of the agency acknowledges the 91% loss of wetlands statewide but does not specifically mention riparian vegetation. However, it is reported that some of the Energy Resource Funds (ERF) being used to fund the program will go towards stream restoration. It would also be useful for the agency to produce a comprehensive biomass production policy that unifies the work and regulations of the DF, CEC, and DFG, specifically addressing the use and re-establishment of fast-growing riparian trees as a fuel source in selected areas.

State Coastal Conservancy

This agency's Coastal Restoration and Enhancement Projects include several wetlands, but have not included work on streams or riparian zones. Guidelines for Coastal Conservancy projects lack a watershed emphasis that would lead to streamside vegetation restoration for wildlife habitat and erosion control. Further, the agency should not invest public money in wetland restoration until the local jurisdiction offers guarantees that it will establish adequate erosion controls (including establishment of statutorily protected riparian zones) in its watersheds, in an attempt to minimize the sedimentation that could erase the public investment in a restoration project in one wet winter.

State Lands Commission

The State Lands Commission, with its Division, is the guardian of the Public Trust Doctrine, a complex legal concept originating in English common law that protects the public interests in tidal areas. This doctrine is receiving increasing attention by such agencies as the USDI Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) as a policy justification for the reservation of instream water rights to protect fisheries, riparian vegetation, and many aquatic wetlands.

The Reclamation Board

The Reclamation Board (RB), which is part of DWR, was created as a result of Gold Rush hydraulic mining, which carried massive sediment into Central Valley rivers, changing flood patterns and reducing navigation. Its primary function is to control encroachments on project levees and those within its defined "designated floodways." On 18 February 1981, the RB adopted an important riparian vegetation policy for designated "areas of critical concern" (but which excludes routine maintenance of levees).

State Water Resources Control Board

The State Water Resources Control Board (SWRCB) is involved in many areas of present interest, but two are especially worthy of comment. The "208" area-wide "nonpoint pollutant" control planning process (from Section 208 of the Clean Water Act[7] ) has given some attention to the vital importance of vegetated streambanks for erosion control and filtration of sediment-carrying runoff, plus the value of wetlands for sediment and pollution filtration. But the program's emphasis on these natural, cost-effective tools has not been sufficient to secure a state-

[7] P.L. 92-500.

wide trend toward their use as "best management practices."

Much more promising is the new program of the SWRCB for retaining instream water flow as part of its water rights program. The regulations are now in place and can be vitally important in protecting the overall health of our streams and many wetlands.

The University System

The revitalization of the Wildlands Resources Center should be expedited to provide a much-needed clearinghouse and "one-stop data retrieval service" for the many university research and reporting services that involve natural resources. The Sea Grant program should be integrated with this center, and a more focussed series of periodic reports should be released to the audience specifically interested in each resources topic.

Wildlife Conservation Board

The Wildlife Conservation Board (WCB) has an active wetland and riparian forest acquisition program.

Overview of California Local Government Programs

While general plan policies are useful and important as educational tools, it is the ordinances of each local government that must be reviewed to determine the effectiveness of any resource management commitment. Not only are there the occasional watercourse ordinances in some jurisdictions, such as Napa County, but most have grading and drainage ordinances that will usually affect vegetative resources. Even weed control ordinances can have an adverse impact on stream systems (there have been occasions when riparian vegetation has been called "water-sucking weeds"!). Subdivision ordinances may also include provisions for stream setbacks or other resource area protections. In Sacramento County there is a "Special Planning Area" ordinance[8] that can allow specialized attention to specific sites, including natural resource areas.

Perhaps the most underused type of ordinance, one that can produce many benefits, is that for floodplain management (nonstructural land-use measures). Such ordinances should require the scientific determination of the high-velocity floodway, which would be a nondevelopment and nonfill zone; the 100-year flood-risk area wherein development must be "floodproofed" to resist damage during the once-in-a-hundred-years flood; wetlands preservation requirements (for both environmental and fiscal reasons); and can include the riparian preservation corridor provisions often found in separate ordinances (it should be noted that in this corridor, even farming must be excluded, while in the flood-risk area farming should be encouraged as a desirable, low-risk use).

Example of a Local Watercourse Ordinance

Several counties have watercourse or stream conservation ordinances, but one of the best known and earliest is that of Napa County. Its Ordinance 447[9] addresses:

. . . protecting the riparian cover within specified distances thereof, providing bonding requirements in connection [with] such permit, providing a fee schedule . . . and abatement as a nuisance such work performed without a permit.

Policy statements in the ordinance acknowledge the interrelationships of flood-hazard areas, public safety, public expenditures for flood protection and emergency relief, riparian vegetation as a "valuable natural resource," and preservation of rural qualities. The preservation of "riparian cover" is specifically declared, to: "preserve fish and wildlife habitats;" "prevent erosion of stream banks;" "maintain cool water temperatures;" and "obtain the wise use, conservation and protection of certain of the County's woodland and wildlife resources according to their natural capabilities."

The ordinance relies on a map on file in the County Office of Engineer to show which watercourses are included, and it states: "There shall be included in the watercourse an area extending laterally outward fifty feet beyond the top of the banks on each side of such channel, except that" a portion of the Napa River shall have a 100-ft. zone. Incorporated cities are excluded from coverage.

A permit is required for the following activities within a watercourse: deposition or removal of material; excavation; construction or alteration of structures; planting or removal of any vegetation; and alteration of embankments. Exceptions to the permit process are given to any public agency; for work in a public right-of-way pursuant to other permits; and for emergency work (which requires a follow-up permit to correct any "impairments"). No application for a permit shall be approved when the Planning Commission finds the proposed work will either substantially impair the water conveyance capacity of the water course or destroy a significant amount of riparian cover."

A final inspection by the County Engineer is required. Any aggrieved person may appeal to the Board of Supervisors. An abatement procedure for violations is established but there is no provision for restoration of vegetation removed in violation of the ordinance.

[8] Sacramento County Code, enacted 1978.

[9] Napa County Code, enacted 1973.

Problems in this ordinance include the above-mentioned lack of restoration responsibility, but more important is the absence of a specific directive to public agencies, which are exempted from the permit process, to follow the intent of the law. The undefined reference to removal of a "significant amount" of cover leaves much room for incremental destruction of the resource outside of the permit process. One Napa County resident expressed the opinion that the control of riparian vegetation clearing for farming purposes has not been vigorous.

Proposals for State Legislation

Comprehensive state legislation is needed to create a consistent, enforceable, effective program for protection of riparian/wetland/floodplain/watershed resources. I propose the introduction of two acts—one like the Oregon bill, SB 397 of 1981—a voluntary approach of preservation and reduced taxation—and another which establishes a regulatory system for the management of multiple related resources. A "California Floodplain Management Act" would provide a unified approach to management of these resources, at the same time providing: long-needed protections of public safety; reduction of public investments in flood control facilities and emergency bailouts for persons who unwisely locate in flood-risk areas; and equity and certainty of treatment (that is, ensuring that the law is applied evenly and fairly to all persons in similar circumstances). In addition, the comprehensive approach to interrelated problems can have a better chance of political success than a focussed, narrower bill which addresses ecological concerns alone.

Some guidelines which should be followed in preparing the act are listed below.

1. No new state agency would be created (although the expansion of the RB in a modified role throughout the state would be helpful).

2. No new state permits would be required—and some could be eliminated.

3. Local governments' land-use planning and regulation processes would be the cornerstone of the system, consistent with state policy in the act, with certification of plans and ordinances by the Resources Agency.

4. The primary vehicle would be a Local Floodplain Program (LFP) prepared by each local government in California, similar to the Local Coastal Programs of the Coastal Act, the Local Protection Program of the Suisun Marsh Preservation Act,[10] and the Local Delta Programs of the proposed Delta legislation now being reviewed by the Resources Agency.

5. The State's role would be to fund the LFPs and to certify the end products as consistent with the state law, and to monitor their implementation and seek judicial recourse where necesssary.

6. Public access to regulated zones would not be appropriate since these would be private lands and the ecology of these areas is sensitive.

Specifically, each LFP would be a combination of amendments to open space/conservation and public safety elements of general plans, land-use maps, and several ordinances. Local governments would be mandated to include the following in their LFPs:

1. Designated floodways for each stream, consistent with federal and state maps (with final arbitration by the RB or DWR);

2. Flood-risk areas covering the 100-year floodplain, with development controls meeting federal and state requirements;

3. Wetland and stream preservation zones, both "primary" and "secondary," as described below.

Setting the Preservation Zone

The definition and mapping of preservation zones for wetlands and riparian corridors is the key issue in the ecological application of the LFP. As suggested by the Coastal Commission review process, it is not as simple as just setting a 100-ft. buffer around a resource area. Multiple considerations should be addressed, including the following:

1. the use of physical features (man-made or natural) to clearly define on the ground the regulatory boundary (especially when the feature can also separate competing uses);

2. controls on the design and siting of uses adjacent to the sensitive resource area (that is, requiring placement of the most neutral activity facing the resource; controlling light and noise from permissible uses; constraining human and pet access with barriers; using landscaping that enhances wildlife values; requiring erosion controls; etc.). In essence, the better the design controls on adjacent uses, the less open buffer is needed;

3. the ecotone or edge considered part of the resource area itself; and

4. the right of the landowner to challenge a boundary by presenting physical evidence (such as soils data) showing the regulatory area to be excessive (as is done in the Connecticut Inland Wetlands Program).

Regarding the last point, for purposes of illustration, consider the result of variably-sized square parcels of land that are edged by a stream. With a 100-ft. non-alteration zone, a one-acre lot is 48% regulated; a 5-acre lot, 21%; a 10-acre lot, 15%; 50 acres, 7%; and 100 acres, 5%. There is no magic percentage at which a "taking" without compensation to the landowner is not a concern, but this kind of evaluation will help planners determine if a narrower zone should be used in specific cases. For a residential or

[10] PRC Section 29000–29612.

commercial lot, the permissible density of any development can be shifted into the area outside the zone, but this is not possible for agricultural lands. Fortunately, most farmlands are large lots, and a 100-ft. band would result in a lower percentage of "taking."

Finally, the different needs for stream and wetland boundaries must be noted; this raises the difference between primary and secondary regulatory zones.

Primary and Secondary Regulatory Zones

In essence, a "Primary Regulatory Zone" involves the actual resource itself—the marsh or the riparian vegetation (and the ecotone) as they are defined by technical or scientific criteria. This is not always easily accomplished and is even more difficult with a riparian zone, where the vegetation has been stripped and the goal is to restore the growth in presently denuded areas.

The "Secondary Regulatory Zone" is, in essence, the "buffer," a term that is often misused. Its purpose is to reduce the adverse impacts of adjacent uses on the resource (within its Primary Regulatory Zone). Therefore, the earlier review of controlling adjacent uses becomes relevant for setting this secondary zone, and again it is to require quality design controls that should be the purpose of setting a buffer.

But there is another complication. For marshes, a further regulatory zone should, ideally, include the entire watershed feeding the wetland, wherein land-use controls would be required to reduce accelerated (human-caused) erosion and sedimentation. Such a third level of regulation could be referred to as the "Watershed Regulatory Zone" for consistency of terminology.

Another point regarding wetlands is that no matter what the size, the "taking" issue should not occur. The public interest in protecting these areas has long been known, as has the poor suitability of wetlands for development. The taking issue in the regulation of wetlands will most frequently arise over the secondary or buffer zone when an agency is attempting to establish a broad non-use area in addition to the marsh itself.

Preferential Assessment

To reduce the concern over the taking issue, it is important that a future act ensure that preferential assessments can be applied to regulatory zones. Such reduction or even exemption from taxation should be left to the discretion of the local government policy board, which can evaluate the request in light of its impact on the jurisdiction's fiscal situation. However, no preferential treatment could occur until the landowner executes a conservation easement in perpetuity. Violation of the terms of the easement should result in at least a penalty of five times the taxes that would have been paid, as is established in the Oregon statute.

The Paradox of Protection Leading to Destruction

Any bill which declares riparian vegetation to be sacred as of the date of its passage will almost ensure the destruction of most of what is left, especially when it occurs on or along farmlands, as landowners rush to remove the cause of more regulation before the law becomes effective. There is no simple means to avoid this, but there must be in the act the use of a date precedent to the bill from which the actual riparian corridor will be measured (prior to the later adjustments, as reviewed above). For instance, in the coastal zone boundaries of all riparian corridors could be drawn to include the vegetation in existence as of 1972, when the voters approved Proposition 20, the Coastal Initiative which included stream protection policies. From that date, it was the State's policy to protect riparian vegetation in this area, and landowners were put on notice. Any cutting of vegetation thereafter would not reduce the width of the regulatory zone. Finding such precedent dates for most of the rest of the state is not as easy, and the provision may have to be hinged upon the general plans of local governments which have riparian policies or other devices (possibly even AB 3147 [Fazio] which mandated the DFG Central Valley and California Desert riparian survey).

The Zones, in Summary

Finally, the major point is that these zones must be variable and subject to change. The primary riparian zone must include: the existing riparian growth; that area which had growth as of a date precedent and shall be set aside for regrowth; the ecotone or edge area; or a 100-ft. band as an interim standard, until the local government can examine each landowner's appeal on the basis of the taking issue, hardship, existing physical intrusions into the zone, and so forth. In the law, the primary wetland zone should be defined by scientific criteria addressing the types of vegetation, type of soil, and the known flow of water. (One clear definition of wetlands must be finally established in California to avoid continuing politically inspired debates!)

The secondary riparian zone should be an area defined by the physical features of the terrain and adjacent uses in which design standards will be required. This would also be the case for the secondary wetland zone. The law can call for the zone to be based on such features, or a 100-ft. band, whichever is greater, as long as it is abundantly clear that this space is not necessarily to remain undeveloped. However, development will only be permitted if the performance requirements can be met.

Finally, for wetlands only a third zone would be required, to permit management of the watershed to reduce erosion and sedimentation.

In fact, California also needs a comprehensive approach to its watersheds and soils. But that is another conference.

Provisions in the Proposed Act for State Agencies

Certain missions of the various state agencies must also be clarified in the new act, including the following.

1. The DWR and the RB process for certifying the LFPs and designated floodplains must be described.

2. All state and local agencies (including special districts) must be directed to conform their plans and programs to the policies of the act and the certified LFPs.

3. The DFG would be directed to plan and implement a statewide site-specific plan for restoration of wetlands and riparian vegetation on state-owned lands.

Conclusions

The technical and political obstacles in both preparing and enacting such a bill as the "California Floodlain Management Act" are indeed huge. But progress has never been made by experts and advocates prematurely surrendering in the face of anticipated political reactions. We must put forth the most workable and streamlined proposal we can design and then go to work on the politics. Several years may be required, but even the Legislature has a way of coming around on major problems that will not go away, no matter how controversial the solutions.

We must secure legislation such as this. If we do not, then I suggest that we will have to take a lesson from the Friends of the River and chain ourselves to the last willows and the last cottonwoods before they are cut, chipped, or burned.

For it will come to that.

Literature Cited

Animoto, P.Y. 1978. Erosion and sediment control handbook. 197 p. California Department of Conservation, Sacramento.

California Coastal Commission. 1981. Interpretive guidelines for wetlands and other wet environmentally sensitive habitat areas. 58 p. California Coastal Commission, San Francisco.

California Department of Conservation. 1979. California soils: An assessment (draft document). 197 p. plus appendices. California Department of Conservation, Sacramento.

California Department of Water Resources. 1982. Policies and goals for California water management for the next 20 years. Bulletin 4, California Department of Water Resources, Sacramento. 52 p.

Office of Planning and Research. 1978. Urban strategy report. 36 p. Office of Planning and Research, State of California, Sacramento.

Office of Planning and Research. 1980. General plan guidelines. 327 p. Office of Planning and Research, State of California, Sacramento.

Protecting Urban Streams—a Case Study[1]

Myra Erwin[2]

Abstract.—The process by which a local government policy regarding urban streams was changed is described. The change was from a policy of channelizing, gunniting, and chain-link fencing to one of minimum modification in the character of the streams and their floodplains.

Introduction

Since the 1940's the character of Sacramento County has been changing. Urban development in the watersheds and floodplains of rural streams intensified many of the problems caused by agriculture (clearing of riparian vegetation, irrigation runoff, etc.). When it became apparent that damage from flooding might become a hazard, and that the costs of repairing such damage could be substantial, the County commissioned a study of county-wide hydrology. The study was to address the drainage problems associated with urbanization and develop a drainage plan. The result was a Master Drainage Plan (Nolte 1961) which called for the channelization of many streams as a means of allowing the maximum development on land adjacent to the streams; that is, on the floodplains. They were, of course, subject to periodic flooding.

During the 1960's and 1970's many streams were channelized, piped or gunnited in order to facilitate urban development. Substantial riparian vegetation was removed; stream sections bordered with large and attractive oak trees were eliminated, straightened, rerouted, and replaced by concrete-lined ditches with 6-ft. high chain-link fences.

But then came the "ecology movement." People everywhere began to question why such things were happening. Wasn't there a way to remove the flood hazards without destroying the environment? Why should we have to destroy our streams, native vegetation, wildlife habitat, and recreation opportunities; and eliminate the air-cooling and -cleaning effects of the riparian vegetation? There must be a better way.

Finding a Better Way

The Beginning

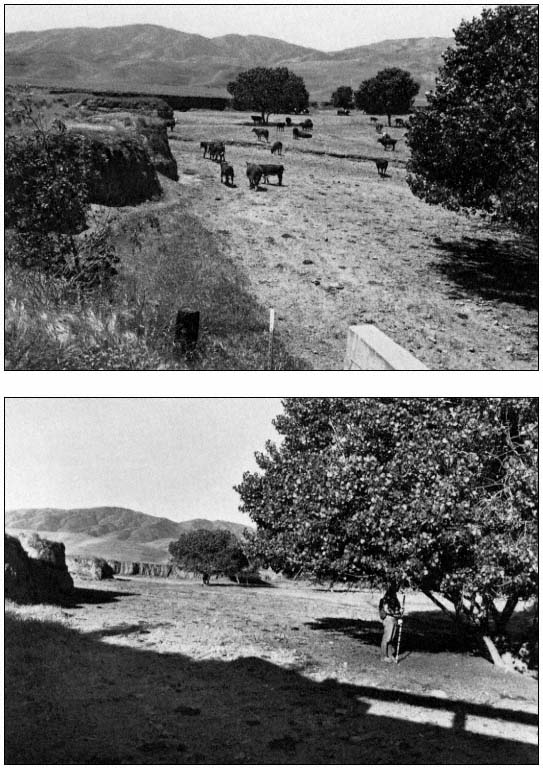

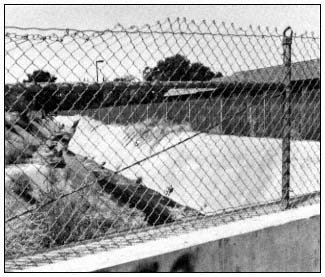

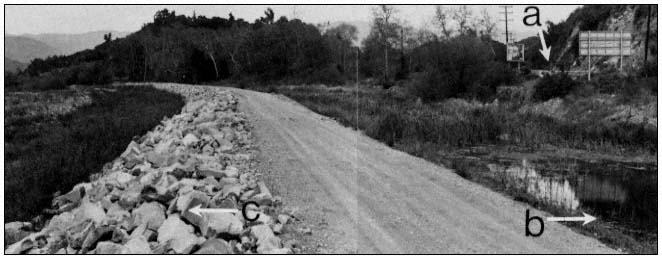

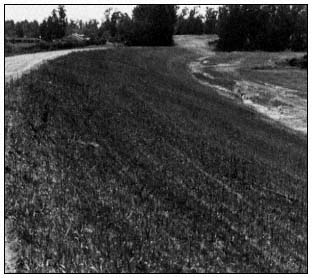

It all started when the Sacramento County Department of Public Works proposed concrete lining and chain-link fencing of Chicken Ranch Slough. Certain sections of the slough had drainage problems which also concerned residents, but the Department's solution to the problems—concrete lining—was an insensitive response to situations where better maintenance or spot solutions (minor channel widening, etc.) would have been appropriate. Property owners along the "slough", which is actually a creek, were incensed. Many of them had, over the years, spent much time and money caring for the native oaks and other vegetation along the stream. Many had beautifully landscaped gardens there. In their view, the proposal would devastate the stream and ruin their gardens. To protect Chicken Ranch Slough, the property owners there banded together and formed the Save Chicken Ranch Slough Association (SCRSA). Figures 1 and 2 illustrate the nature of the problem. Figure 1 is an example of the traditional channelization, gunnite, and chain-link fencing approach. Figure 2 shows the natural character of the streams in question, which residents wanted to protect.

Identifying the Problems

Before long the Environmental Council of Sacramento (ECOS), a coalition of local environmental and civic organizations, joined in and soon took a leading role in the effort to protect not only Chicken Ranch Slough but all the streams threatened by so-called "improvement." Property owners along these other streams had also become aroused. At a very well attended hearing, the Board of Supervisors directed the Department of Public Works to prepare a new plan for the streams. Many thousands of dollars and many months later, their plan, consisting mainly of sets of large-scale aerial photos and water profile maps, was finally presented to the Board and the public. Those in attendance milled around, trying to understand the maps and photos pinned to the walls all around the room. Few, if any, understood. So an accompanying text was

[1] Paper presented at the California Riparian Systems Conference. [University of California, Davis, September 17–19, 1981].

[2] Myra Erwin is a member of the California Regional Water Quality Control Board, Central Valley Region; and Chair, Sacramento County Natural Streams Task Force, Sacramento, Calif.

Figure l.

The channelization, gunnite, chain-link approach on

one of the County's streams. Aesthetic, ecological,

and recreational values have been destroyed.

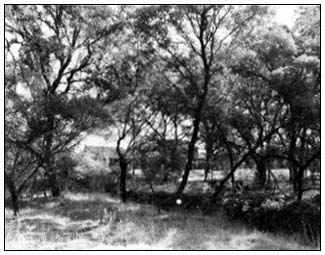

Figure 2.

A County stream with native riparian vegetation and

floodplain pattern intact. Ecological, recreational,

and aesthetic values have been retained.

demanded. The Board of Supervisors also recognized that recreation and planning considerations had not been included. Not only should existing drainage problems be corrected, but new ones should be prevented. The Board ordered that a comprehensive environmental impact report, to include these considerations, be prepared. The resulting Sacramento County Natural Stream Study (Environmental Impact Section, County of Sacramento 1974) became the explanatory document for the Master Drainage Plan.

However, now that they understood the Plan, and its recommendations for "improving" the streams, neither the SCRSA nor ECOS was satisfied. These organizations insisted that the channelizing and gunniting must stop. The streams must be left as natural as possible. At this point, the ECOS recommended to the Planning Commission that a broad-based task force, comprised of public members representing citizens' groups, and staff members from relevant departments and agencies, be appointed to develop new County policies which would protect the natural character of the 13 designated streams, provide for appropriate recreation, and at the same time prevent flood hazards. To prevent a foreclosure of options while the task force was developing new policies, a moratorium on development adjacent to the streams was recommended. The moratorium was to be effective until the task force's work was completed. The Planning Commission concurred and made these recommendations to the Board of Supervisors. With the Board's adoption of Resolutions 74–1173 and 74–1283, the moratotorium went into effect and the Natural Streams Task Force was created.

The Natural Streams Task Force

Organization and Structure

The Task Force was indeed structured to involve citizens' groups as well as County staff (see table 1). Certain State and Federal agencies were also invited to attend, which they did initially. However, after giving some input they felt they were no longer needed and no longer attended the meetings.

The Task Force's Coordinator was from the County's Environmental Impact Section. He had a formidable task, faced with the necessity of getting a consensus from mutually suspicious Task Force members with diverse and often conflicting concerns.

| ||||||||||||||||

After election of the Chair (the ECOS representative and the only woman), the orientation and education of the Task Force citizen-group members began. There was a great deal to learn about hydrology and existing zoning, grading, and drainage regulations. At the same time, the Task Force Coordinator was developing a work plan to guide the Task Force's efforts in its development of the Natural Streams Plan.

Assignment of Responsibilities

After the work plan was adopted, each citizen-group member was assigned one or more streams as his or her particular responsibility. To gain first-hand knowledge of the problems and opportunities, the members walked the length of "their" streams, often along improvised trails, which were there simply from neighborhood use, often struggling through underbrush and over wire fences. Also, staff members made field inspections of the streams and their environs, for recreation and open space opportunities, and for aquatic and riparian wildlife and vegetation, adding many hours of volunteer time. The Health Department's representative checked for water quality problems, and the Planning Department's member delineated existing zoning districts along the streams.

In due course, public meetings were held, one in the vicinity of each stream, conducted by the appropriate Task Force member. Those individuals who had earlier indicated their interest were kept informed of the Task Force's meetings, and were invited to attend the local meeting on the stream of their concern. In addition, notices were sent to all streamside property owners, and there was good attendance at the meetings. The consensus at all of these stream meetings was: LEAVE THE STREAMS AS THEY ARE!

Administration Problems

As the Task Force proceeded, it became evident to the citizen-group members that responsibility for the administration of uses within the streams' floodplains was fragmented among the participating County departments and that communication and cooperation among the departments had been ineffective or non-existent in the past. It was also noted that some specific recommendations adopted by either of the planning commissions or the Board of Supervisors were not being adequately implemented by the responsible County officials. Further, there was a conspicuous lack of data on existing operations. But most important of all, there was a lack of county-wide comprehensive policy regarding land use within the floodplains. In fact, it was not unusual to find policies calling for the protection of floodplains, while adopted Department of Public Works proposals called for the channelization of those same streams.

A Basic Conflict

Task Force members wrangled interminably, it seemed. Citizen-group members wanted drastic changes in policy and procedures, while the Public Works members held fast to established practices, trying ineffectively to explain why they were necessary. The conflict stemmed primarily from the following diametrically opposed perceptions: the recognition, on the part of most of the citizen-group and some staff members, of the need to stop building in the floodplains; versus the persuasion, on the part of the Public Works member supported by the building industry member, that the only reasonable way to prevent flooding and allow reasonable use of private property was to continue the drainage "improvement" measures of the past.

Figures, formulae, and data supporting different points of view generated reams of reading material for the Task Force.

Floodplain Development Moratorium

All this time, at almost every meeting there were at least one or two proposed development projects near streams to review. Under the moratorium, projects adjacent to the floodplains needed Task Force approval. The Task Force knew it was important to be reasonable rather than arbitrary in order to maintain its credibility with and support from the Board of Supervisors, especially since any decision by the Task Force could be appealed to the Board. Consequently, reaching an agreement on the treatment of the floodplains which was satisfactory to both sides was very time-consuming. Even so, agreement was not always attained.

The first appeal by a developer to the Board was rather frightening to some Task Force members. The project was a subdivision proposal. The small stream or swale which ran through the site was to be piped and houses were to be built over it—at least piping was the choice of the proponent and the recommendation of the Department of Public Works. The case could perhaps be considered borderline: the swale in question was near the headwaters of the stream and in summer carried only a small amount of urban runoff. But the Task Force was concerned that downstream flooding could occur during the winter season as a result of the concentration of flow. Also, a very nice clump of vegetation, plus the rolling nature of the land lent itself to an urban design which could include the stream.

A majority of the Task Force was worried. Would its recommendation to retain the natural character of the stream and incorporate it into the design of the project be upheld, and the request to pipe the stream and fill the floodplain be denied? Or would the developer win and set a precedent which would become a serious obstacle for the protection of other natural streams and floodplains in the future? It was a hard-fought battle—the developer was one of the biggest and most influential in Sacramento, and this kind of stream had always been piped in previous developments. But despite a recommendation in favor of the developer from the Subdivision Review Committee (the County's technical

advisory committee), the Planning Commission recommended denial of the piping and adoption of the Task Force recommendations. The Board of Supervisors concurred.

This was a turning point for the Task Force. Henceforth, it was known that the Board's moratorium policy and the Task Force's recommendations were not to be trifled with, and developers would fare better by incorporating the Task Force's recommendations into their projects.

It was a stimulating experience for the Task Force members and they plunged into their work with renewed vigor.

Policy Guidelines

The burden of reviewing projects was made heavier by the need to review those which were located along tributaries as well as along the main channels of the designated streams. To help organize and standardize the review process, the Task Force developed policy guidelines, including a list of information requirements from project proponents, and a map designating the subject tributaries, for consideration by the Board of Supervisors. An enormous amount of work and argument preceded the completion of the Tributary Policy, but it was finally adopted by the Board of Supervisors.[3] From then on projects adjacent to tributaries were administered by staff and the Task Force no longer had to spend precious time on them.

Specific Flooding Problems

One more time-consuming activity which slowed development of the Natural Streams Plan was the need to make recommendations on specific flooding problems. Both the County and the property owners presented proposals relating to stream preservation versus reduction of existing flooding. The Task Force worked hard on these issues and after considerable discussion with all sides, an agreement was generally reached without the need for an appeal to the Board of Supervisors.

Stream Maintenance

Because of the need for data on methods and costs of the County's stream maintenance program, and for information on methods of enforcing existing as well as future ordinances, two Task Force committees were formed. The Maintenance Committee's Chair was an expert at data gathering, and with the assistance of the Public Works staff, he did a professional analysis (all volunteer work) of stream maintenance practices and costs. To the surprise of some, it turned out that the costs of maintaining the streams in their natural state would generally be lower than the total costs for channelized streams if the Task Force recommendations were followed. These recommendations would make the maintenance program self-supporting by improving the revenue system, labor practices, and operational procedures. Ultimately, these recommendations were included in the maintenance element of the Natural Streams Plan.

Enforcement of Existing Regulations

How to enforce regulations prohibiting rubbish dumping, illegal filling, and other modifications of the floodplain was a persistent problem. The Enforcement Committee Chair himself lived near one of the streams and was determined to find solutions to the enforcement problems. The enforcement element of the Natural Streams Plan is mainly the result of his committee's work.

Floodplain Management Element

But of all the elements of the Natural Streams Plan, the floodplain management element was the most controversial and took up a preponderance of the Task Force's time. A basic disagreement among Task Force members was over the "taking" issue: in this case, whether a dedication to the County of floodplain land could be required as a condition of development. Department of Public Works and building industry members argued that floodplains can be filled, thus removing the flood threat on the filled land—there would then be no justification for requiring a dedication. But a majority of Task Force members maintained that filling simply squeezes the water into a narrower channel, raising the water level, increasing its velocity, causing erosion and flooding downstream of the fill, in addition to destroying the riparian vegetation which often is abundant in the floodplains. They argued that the safest, cheapest, and most desirable flood control method was to prohibit any development at all in the floodplains.

The first County Counsel's representative to the Task Force prepared a paper explaining the legal issues and apparently leaving the door open to consideration of prohibitions on floodplain development. But later he was replaced, and his successor prepared a highly critical paper which said that the real purpose of the proposed restrictions on floodplain use was "the protection of aesthetic and recreational values, rather than the protection of public health and safety . . ." and therefore they would likely be held unconstitutional as a "taking of private property without compensation."

In the meantime, Federal agencies, in particular the US Army Corps of Engineers, were ordered by the President to prevent development in floodplains partly because of the discovery that enormous expenditures of taxpayers' money were used to rehabilitate floodplain property and reimburse occupants whose property had been flooded. It seemed only prudent to avoid building in floodplains. During the early years

[3] The Tributary Policy was presented as a report by the Natural Stream Task Force, and adopted by the Board on April 7, 1976.

of the Task Force's work, the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) was developing rules for Federal flood insurance and the Corps of Engineers was delineating the 100-year floodplain for streams in Sacramento County. The fact that the Federal government was recognizing the hazards and costs of floodplain development gave more credence to the position of the Task Force majority.

In any case, the County Counsel's advice was, in effect, sidestepped when the Task Force adopted recommendations for the Board of Supervisors which included severe restrictions on floodplain development.

The Issue of Cost

Another area of great controversy was the cost issue. The question of maintenance costs has been mentioned above, but there was also the question of costs of the recreation element. There were bicycle trails and recreation areas to be provided—the preliminary cost estimates were clearly beyond the County's capability, even in the long run. However, the Task Force discovered that the figures used to project the costs were based on total purchase of the floodplains and excessive size and construction standards of the bicycle trails. With the inclusion of floodplain dedications, and restriction in the length and construction standards of the bike trails, the costs were brought down to reasonable levels. Recommendations for financing methods as well as a long-range time schedule for implementation of the recreation element were also included.

The Time Factor

Task Force members, during the five years they worked on this Natural Streams Plan, often felt great impatience and frustration with the snail's pace of its progress. There were two or three periods of several months with no meetings and no action at all due to the staff members preemption for higher priorities of the Board of Supervisors. But this long duration worked to the advantage of the goals of the Task Force partly because of the rapidly changing attitudes all over the country regarding environmental issues. Even more important, considerable development occurred in lands adjacent to the floodplains, using the Task Force's preliminary guidelines. That meant that by the time the Natural Streams Plan was ready to present to the Planning Commission and the Board of Supervisors, it had been demonstrated that the floodplain guidelines were not all that onerous, and could result in some very attractive developments with the stream as a sales feature.

The Final Plan

The final Plan, as should be expected, was a compromise. Nevertheless, it was a good compromise from the Task Force majority's point of view.

In preparation for the public hearings on the Plan, a handsome, green and white, glossy brochure was distributed to each streamside property owner. These brochures described the proposed Natural Streams Plan and announced the public hearings to take place over a period of time. Excellent parcel maps were included, showing the stream and the approximate area proposed to be included in the Natural Stream Zone. In addition, the brochures advised residents what to do to protect the streams. Although some Task Force members were apprehensive about possible opposition at the hearings, none materialized, and the Plan was adopted by the Board of Supervisors in July 1980, five and one-half years after the appointment of the Task Force. Seeing the adoption of its recommendations, the Task Force was able to retire with a profound sense of satisfaction and relief.

Epilogue

As far as we can tell, one year after adoption of the Natural Streams Plan, the floodplain management aspect of the Plan has been very effective in preventing encroachment on the streams' floodplains, which in turn has eliminated the need for channelization of additional streams. This is due largely to the interest taken in the Plan by the Planning Commission staff and their determination to see that the new regulations are implemented. Their task is made relatively simple by the new Natural Streams Zone established as recommended by the implementation element of the Plan. The County's drainage, grading, and subdivision ordinances were also amended to make them consistent with the Plan's objectives and policies.

Because of financial constraints, the recreation element is in a holding position, but at least the land in the floodplains will be available for recreational uses in the future.

Looking back, it seems quite remarkable that almost all the citizen-group members stuck it out through more than five years of very difficult meetings. Perseverance is perhaps the most needed attribute necessary for the success of citizen action. However, in the final analysis, it was the responsiveness of the Board of Supervisors to the large number of residents who cared about their streams that has made the Natural Streams Plan truly effective.

Literature Cited

Environmental Impact Section, Sacramento County. 1974. Sacramento County natural stream study. PW-74-003. Sacramento County, California.

Nolte, George S. 1961. The County of Sacramento master drainage plan. Part 1—county-wide hydrology. Sacramento County.

San Diego County Riparian Systems

Current Threats and Statutory Protection Efforts[1]

Gary P. Wheeler and Jack M. Fancher[2]

Abstract.—The effectiveness of present laws in conserving San Diego County riparian systems is examined. Agencies are more effective when several laws apply, when credible statutory authority and enforcement exists, and when public support is generated. Recommendations are made for improvement.

Introduction

The Mediterranean climate of coastal southern California has induced some obvious and distinct contrasts between mesic and xeric vegetation-types. Coastal sage scrub, chaparral, oak woodland, or California grassland vegetation often ends abruptly at a narrow corridor of riparian vegetation. Woody, perennial wetland vegetation is usually confined to a relatively narrow corridor bordering the enduring, year-round, low-volume water flows and is not directly correlated with the mean annual or ephemeral high-volume storm flows. Consequently, unmodified floodplains in southern California are often relatively wide when compared with the narrow strip of riparian vegetation which frequently occurs only along the path of low flow.

The Mediterranean climate may, in part, have promoted human occupancy of southern California floodplains by fostering the false impression, for decades at a time, that riparian growth delimited the floodplain. Following the rare but inevitable devastating flood, the typical human response has been to "improve" the floodplain to accommodate this rare flood. In doing so, headwaters are dammed, and the natural floodplain usually is constricted into a channelized floodway in order to provide protection for floodplain developments. To maximize hydraulic efficiency, riparian vegetation is typically removed. The trapezoidal, concrete channel of the Los Angeles River is a famous example of such maximized hydraulic efficiency.

Since more than half of all Californians live in the four coastal counties of southern California (Ventura, Los Angeles, Orange, and San Diego), unmodified riparian corridors have largely been obliterated. Some significant areas of riparian vegetation do exist, particularly in San Diego County. In some San Diego County rivers, such as the Mission Valley region of the San Diego River, historic sand mining has brought riverbottom elevations nearer to the water table, which facilitated marsh and riparian woodland establishment once mining ceased. Also, the reestablishment of perennial freshwater flows by irrigation and wastewater returns encouraged wetlands redevelopment. However, riparian wetlands continue to be threatened by human actions. Using actual case histories, we will attempt to document the major threats to coastal San Diego County's riparian resources and the effectiveness of agencies in protecting these resources; and we will offer some general observations as to what factors influence the effectiveness of attempts to protect riparian systems.

The Riparian Resource

San Diego, the southwesternmost county in the mainland United States, encompasses approximately 1.1 million hectares (2.7 million acres) of land ranging from coastal beaches and plains to foothills, mountains, and desert. Riparian systems are extremely limited within the county, occupying somewhere between 0.2% (2,000 ha. [5,000 ac.]) (California Department of Fish and Game 1965) and 0.5% (5,300 ha. [13,000 ac.]) (Oberbauer 1977) of the county's land area.

Riparian vegetation to some degree can be found along most of the coastal region streams; however, the most prominent locations include the mouth of San Mateo Creek, Las Pulgas Creek, the Santa Margarita River, the San Luis Rey River, Las Penasquitos Creek in Sorrento Valley, San Clemente and Rose canyons, the San Diego River, the Sweetwater River, Jamul Creek, Campo Creek,

[1] Paper presented at the California Riparian Systems Conference. [University of California, Davis, September 17–19, 1981].

[2] Gary P. Wheeler and Jack M. Fancher are Biologists with the USDI Fish and Wildlife Service, Laguna Niguel, Calif. The opinions and recommendations offered in this paper are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the USDI Fish and Wildlife Service.

and the Otay River (Goldwasser 1978). Willows (Salix spp.) tend to dominate the riparian vegetation in most areas; however, cottonwoods (Populusfremontii and P . trichocarpa ), California sycamore (Platanus racemosa ), and white alder (Alnusrhombifolia ) are also major components in various areas. Understory vegetation commonly includes mugwort (Artemesiadouglasiana ), mulefat (Baccharisviminea ), stinging nettles (Urticaholosericea ), and wild cucumber (Marahmacrocarpus ). Oak woodlands dominated by coast live oak (Quercusagrifolia ) and canyon live oak (Q . chrysolepis ) in several areas border or intermix with riparian systems, particularly in the more inland canyons (Oberbauer unpublished).

Threats

Current threats to San Diego County riparian systems can generally be tied to population pressures and/or pressure for development. Just within the past 10 years, the county's population has increased by approximately 0.5 million people, a 37% increase. The county General Plan Conservation Element (San Diego County 1980) states that vegetation removal is the single most important human action impacting local wildlife. Vegetation removal is not subject to the county environmental review process, and large areas are sometimes cleared for agricultural purposes or residential development prior to filing an environmental impact report. Stream channelization, floodplain filling, and sand and gravel extraction are occurring at a particularly rapid rate along the San Luis Rey River near Oceanside and along the upper San Diego River, and have resulted in major losses of riparian resources along these streams. The proposed construction of two dams and reservoirs on the Santa Margarita River near Fallbrook threatens to inundate over 400 ha. (1,000 ac.) of riparian and oak woodlands.

Tools for Protection

Several means for countering these threats are available to concerned citizens and public agencies. The National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA)[3] and California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA)[4] constitute disclosure laws which, in themselves, do not directly protect riparian resources, but do require identification of alternatives and assessment of project impacts. Similarly, the Fish and Wildlife Coordination Act (FWCA)[5] mandates consideration of fish and wildlife values in the planning of federal water development projects and issuance of US Army Corps of Engineers (CE) permits, but has no enforcement or implementation provisions. Presidential executive orders such as E.O. 11988, Floodplain Management, and E.O. 11990, Protection of Wetlands, provide guidance in project planning to federal agencies. State, county, or municipal ordinances and policies generally also provide guidance, but rarely include significant enforcement features. Regrettably, the parochial attitude of most southern California city and county governments has usually resulted in the encouragement of developments which increase the tax base but may result in significant environmental losses.

Two state and two federal laws include enforcement provisions. Because of varying legislative intents and jurisdictions, these laws differ in their effectiveness for protecting riparian resource values.

The California Coastal Act of 1976[6] (CCA) provides emphatic and effective protection of riparian wetlands as environmentally sensitive habitat. Under the CCA, environmentally sensitive habitats are to be protected against any disruption of habitat values which could occur from development within or adjacent to that habitat. Furthermore, only uses dependent upon the sensitive resource are allowed within the area. Removal of riparian vegetation and streambed materials is also controlled by the act. However, the geographic extent of the protection afforded by this strong habitat protection law is severely limited when related to the distribution of riparian systems. The CCA permit process includes public hearing and California Coastal Commission deliberation steps.

Division 2, Chapter 6 of the California Fish and Game Code (California Fish and Game Commission 1979) states: "The protection and conservation of the fish and wildlife resources of this State are hereby declared to be of utmost public interest." The subsequent Fish and Game Code sections 1601 through 1603 have a very broad geographic applicability, covering virtually all streams within the state. These code sections require a Streambed Alteration Agreement between the California Department of Fish and Game (DFG) and any party proposing to alter or modify a streambed, channel, or bank. The major weakness of this regulation, aside from the manpower and time constraints placed upon the DFG, is that an arrangement agreeable to both parties must be reached between the DFG and the developer. The discretion to deny a project which would cause significant damage is not available. In order to reach an agreement, a compromise is normally required, and the existing resource is seldom preserved intact. If agreement is not reached, a three-member arbitration panel is formed to resolve any differences. For various reasons, it is apparently the unstated policy of DFG to refrain from entering arbitration, since fewer than 0.02% of the streambed alteration notifications have been taken to that level of consideration.

[3] 42 U.S.C. 4321–4337; 83 Stat. 852.

[4] PRC Section 21000–21151.

[5] 16 U.S.C. 661–666(c); 48 Stat. 401 (as amended).

[6] PRC Section 30000–30900.

The federal Endangered Species Act (ESA)[7] as amended, stringently guards listed species against adverse impacts caused by federal actions. However, this act applies only when a listed species and a federal action are involved. Currently there are no federally listed riparian woodland-dwelling species in San Diego County; therefore, the ESA is rarely invoked when riparian woodlands are to be affected. Activities involving certain vernal pools, a rare and unusual riparian system, have been restricted under the ESA due to the presence of the San Diego mesa mint (Pogogyne ambramsii ), a federally listed Endangered species.

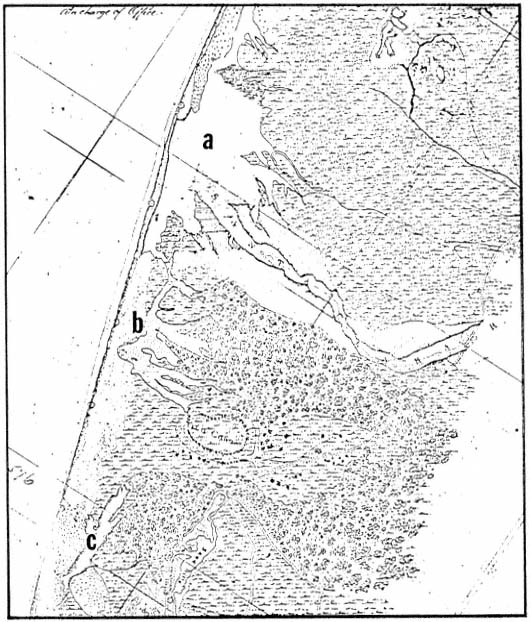

The federal law most frequently invoked in the protection of riparian resources is the Clean Water Act.[8] Section 404 of the act calls for regulation of the discharge of dredge or fill material into waters of the United States. The permit process, administered by the CE, includes distribution of a public notice and a broad public interest consideration. The Clean Water Act does not restrict excavation within wetlands or clearing of wetland vegetation when no discharge occurs. Jurisdiction requiring individual permits is limited to watercourses, and their adjacent wetlands, conveying an average annual flow of 0.14 cu. m. (5 cu. ft.) per second or greater. Consequently, only major rivers or perennial streams are included, as shown in table 1.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Case Histories

The following four case histories are presented as examples of the threats posed to San Diego County riparian systems and to demonstrate the effectiveness of our current laws in protecting them.

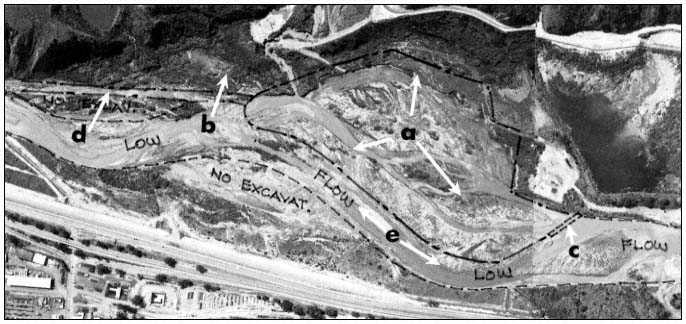

San Diego River

In the fall of 1980, a private developer began to clear and fill an area of riparian woodland within the San Diego River floodplain in the city of San Diego. Approxmately 0.5 ha. (1.2 ac.) of large-stature black willow (Salixgooddingii )-dominated woodland had been leveled, and filling had begun when a DFG warden stopped the work. The developer had obtained neither a streambed alteration agreement with the DFG nor a Section 404 permit from the CE.

The CE would not consider prosecution of this unauthorized act and, instead, expressed a willingness to accept an after-the-fact permit application. The DFG considered prosecution for failure to notify under the Fish and Game Code, but due to limited state resources available for litigation, chose to prosecute an unrelated but similar violation upstream.

As the threat of state and federal prosecution disappeared, the developer's negotiating position significantly improved. The mitigation proposals initially forwarded to the agencies by the developer were minimal and did not offset the loss in riparian values. In the negotiation process, it was revealed that the city had not only required the developer to complete a dedicated street through the subject wetland, but also that the city owned the wetland property. Further, the unauthorized roadway clearing and filling had isolated another 0.4-ha. (l.l-ac.) parcel of wooded wetland owned by the city, which the city ultimately wanted to fill and sell for development. The developer, acting as the city's agent, initiated the agreement procedure with DFG. Apparently because of the time requirements of the agreement procedure, the lack of prosecution, and the unwillingness of the developer to remove the fill, DFG reached an agreement with the developer at a time when the USDI Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) was still seeking an acceptable mitigation plan.

The city and the developer considered unacceptable any plan which did not allow them to complete 0.9 ha. (2.3 ac.) of fill in the wooded wetland. Under the streambed alteration agreement, the DFG had agreed to this fill provided that 1.9 ha. (4.6 ac.) of adjacent land owned by the city of San Diego were excavated to create wetlands and then revegetated.

The FWS contended that even though 2 ha. of wetland were to be gained for each hectare lost, a loss of habitat values would result. This position was based upon the premise that 1 ha. of mature riparian woodland provides greater habitat

[7] 16 U.S.C. 1531–1543; 87 Stat. 884.

[8] 33 U.S.C. 1251–1265, 1281–1292, 1311–1328, 1341–1345, 1361–1376; 86 Stat. 816, 91 Stat. 1566.

values than 2 ha. of open water and early successional wetlands characterized by herbaceous hydrophytes and sapling willows and cottonwoods. Also, because of the uncertainties of transplant survival, the modified hydraulic regime of the river, and the unpredictability of seasonal storm flows, FWS incorporated a safety factor in its mitigation recommendations and suggested that 1.6 ha. (4 ac.) of wetlands be created for each 0.4 ha. (1 ac.) of riparian wetland to be filled.

The developers then hired a biological consultant who contradicted the FWS habitat assessment. They also lobbied the CE, as well as the FWS Washington office, charging that the FWS recommendations were excessive and unreasonable, since they went beyond those which had satisfied the DFG. When the FWS held firm, the developer and the city recognized that project delays could result.

Since delay was contrary to the developer's interests, the developer encouraged the city to become directly involved and to consider guarantees for the compensating wetlands. Eventually a mitigation plan was agreed upon which assured long-term protection of wetland habitat values.

The elements of the mitigation plan, which offset the loss of 0.9 ha. of forested wetland included: a) creating 1.9 ha. of wetland by excavating a sparsely vegetated upland down to riverbottom elevations; b) revegetating the newly created wetland with a variety of native riparian plant species, with maximized edge effect, foliage height diversity, and wildlife cover and food values given special considerations; c) assurance by the developer, through a letter of credit, that for five years the 1.9 ha. transplant effort will succeed (wetland re-creation success will be evaluated over the five-year period using avifauna and vegetation monitoring studies); d) an agreement by the city with FWS, using a deed restriction instrument, to preserve the fish and wildlife resource values of 4.5 ha. (11 ac.) of city-owned San Diego River wetlands (1.9 ha. of compensation area plus an additional 2.6 ha. [6.4 ac.] of contiguous forested wetland); and e) an agreement whereby the city will not propose any work in another 2.6-ha. (6.5-ac.) parcel of contiguous forested wetland until a management plan for preserving San Diego River wetland values is implemented.

San Luis Rey River #1

A housing development proposed for construction adjacent to the San Luis Rey River in northern San Diego County included a street which was to encroach upon a riparian wetland composed mainly of giant reed (Arundodonax ) and a single row of large cottonwoods (Populus sp.). Prior to the public comment period required under Section 404 of the CWA, a streambed alteration agreement requiring no extensive mitigation was signed by the developer and DFG.

Upon distribution of the CE public notice on the project, the FWS, DFG, and Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) objected to the issuance of the permit unless the loss of riparian resource values would be mitigated. The FWS encouraged the developer to find an alternative route for the encroaching roadway, but was informed that a City-designated street corridor and safety criteria prohibited relocation. At this point the developer offered to create a new riparian wetland by lowering the elevation of a nearby upland area of equal size.

Prior to removing its objections to the issuance of the Section 404 permit, the FWS requested that the developer prepare a satisfactory revegetation plan. A consulting firm was employed to develop the plan, which consists of grading the plot to varying heights above the riverbed and planting native willows, cottonwoods, sycamores, and a variety of understory species. A hedgerow of armed vines and shrubs was included to prevent excessive human intrusion. Irrigation was to be provided if necessary, and a planting survival rate of 80% after two years will be considered a successful transplanting effort.

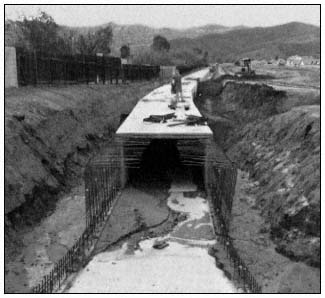

San Luis Rey River #2

On the San Luis Rey River near the city of Oceanside, there is an isolated business and several residences which could only be reached by traversing a low, culverted river crossing. This crossing would typically wash out with any significant floodflows in the river, thereby further isolating the business and the residents. Consequently, the business owners and area residents decided to build a bridge across the river. The bridge was begun prior to notifying Oceanside city authorities, DFG, or CE to obtain necessary permits. In the construction process approximately 0.4 ha. (1 ac.) of riparian woodlands were cleared and filled.

The DFG filed suit against the owner/builder for failure to notify DFG under Fish and Game Code Section 1603. In deciding the case, the judge ruled against the DFG, stating that there was no substantial alteration of the streambed or bank and that, in the absence of a definable riverbank, the ordinary citizen could not be expected to know that the bank extended to the outward edge of the riparian vegetation.

Fortunately, this portion of the San Luis Rey River is also under CE Section 404 jurisdiction. Although the CE would not prosecute the owner/builder for failure to obtain a permit prior to construction, it appears that, based upon recommendations by DFG, FWS, and EPA, the builder will be required to revegetate the riverbank in order to obtain a CE permit for retaining the bridge approach fills. The city permit required no mitigation of adverse impacts to San Luis Rey River riparian resources.

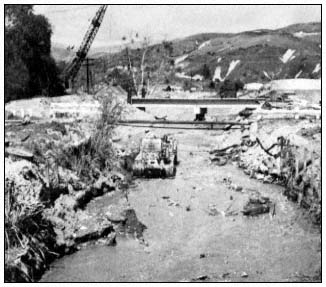

San Luis Rey River #3

In 1966, an industrial manufacturer constructed a plant within the floodplain and an historic channel of the San Luis Rey River. Apparently, his action was based upon the belief that the CE would soon implement a proposed channelization and flood control project along the river. This has not yet occurred, and since construction, floodflows have inundated the facility five times. Due to the delay in construction of the CE flood control project, the developer himself has attempted to protect his plant by rerouting the river north of his plant, constructing a levee along the south bank of the river, clearing the river channel of riparian vegetation, and constructing a ring levee around his plant. With each inundation, greater flood control measures have been implemented and more riparian wetlands have been adversely impacted. On several occasions fill material was placed in wetlands prior to obtaining a CE permit or DFG agreement. The CE has been reluctant to prosecute the developer under the provisions of the CWA, and the developer considers his actions justified, claiming that all actions he has taken have been either under an emergency situation to protect lives and property or have been in the public interest to protect the jobs of his many employees.

The DFG has filed suit against the developer under Section 1603 of the Fish and Game Code for failure to notify the agency prior to altering the stream. This suit is pending and, as yet, no court date has been set.

The developer has indicated his intention to construct a major industrial complex adjacent to his plant in an area currently supporting a lush riparian woodland. His initial step will be to clear and farm this area. Provided there is no addition of fill material, the Clean Water Act does not require a permit for farming of wetlands. It remains to be seen if Section 1603 of the Fish and Game Code will offer any degree of protection for this area. The future of this riparian woodland, however, does not appear to be very promising.

Discussion

Several general points should be considered as one evaluates the relative degree of protection achieved in these cases.

The greatest degree of protection occurs when several agencies have authority for project review under different statutes with similar objectives. This was demonstrated in the San Diego River case and in San Luis Rey #1 and #2. In each of these examples a weaker streambed alteration agreement was backed up by more stringent conditions requested by the DFG, FWS, and EPA on the Section 404 permit. Even though Fish and Game Code sections have protection and conservation of fish and wildlife resources as their purpose, implementation by DFG is debilitated by the impotent statutory vehicle. Had these actions occurred within the jurisdiction of the California Coastal Commission, it is suggested that wetland values might have been even better conserved.

A greater degree of protection seems to result when opportunity for public review and comment is provided. We have seen on several occasions where public comments provided to the CE have influenced the issuance of a Section 404 permit. The influence of public involvement on private projects, however, can perhaps best be seen in observing the public hearing process of the California Coastal Commission where a multitude of opportunities are provided for meaningful public input.