Part 2

4. Children of the State

Children in orphanages are state children.

Their father is the state and their mother is the whole of

worker-peasant society.

Prison, prison! What a word,

Shameful, frightful to the ear.

But for me it’s all familiar,

I have long since lost my fear.

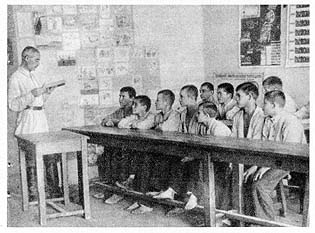

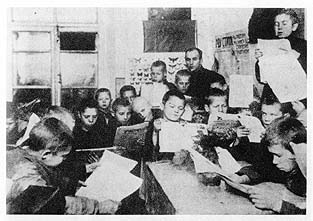

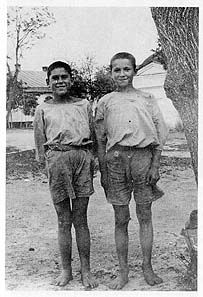

In the heady days of revolutionary triumph, the new Bolshevik government sought to take upon itself the task of feeding, clothing, and even raising a large share of the country’s children. Decrees instructed central and local agencies in 1918 and 1919 to arrange the distribution of food to juveniles—free of charge—from schools, special dining halls, and other outlets.[1] As late as July 1921 the Council of People’s Commissars (Sovnarkom) noted that while the rest of the population was expected to provide for itself, the state would continue to assume responsibility for supplying food to minors.[2] More ambitious still, Narkompros and other government agencies anticipated the development of a network of children’s homes that would be capable before long of raising the nation’s offspring.[3] Enthusiasts viewed the institutions as far better equipped than the “bourgeois” family to fashion youths into productive, devoted members of a communist society. What task could be more important, they asked, than replacing the traditional family environment—often steeped in ignorance, coarseness, and hostility toward the Bolsheviks—with homes administered by the government itself?[4] “The faculty of educating children is far more rarely encountered than the faculty of begetting them,” observed The ABC of Communism. “Of one hundred mothers, we shall perhaps find one or two who are competent educators. The future belongs to social education.”[5]

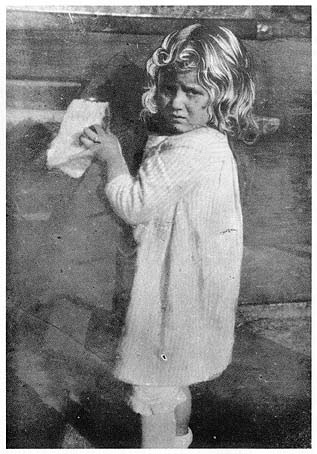

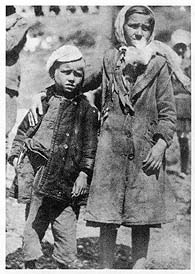

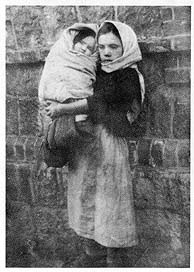

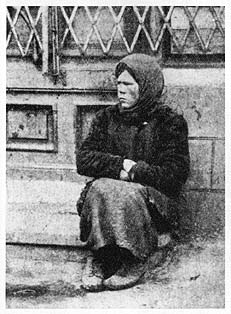

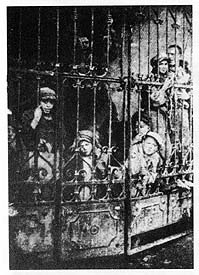

Ambitious in the best of times, these plans were deflated by the dire reality of the Soviet regime’s early years. As millions of waifs overwhelmed government institutions and budgets, Bolshevik hopes of rearing most other youths appeared practical only to unflinching visionaries. Children’s homes may have been intended originally for all juveniles, but they soon acquired a reputation as refuges for the multitude of young vagabonds bred by war and famine. Even this restricted clientele proved so vast that most facilities could long do little more than struggle to prevent their charges from dying or running away. The goal of a socialist upbringing retreated to await more auspicious days.[6]

| • | • | • |

As commissariats of the Soviet government took shape following the Revolution, rivalry soon developed among three of them—Narkompros, the Commissariat of Health, and the Commissariat of Social Security—over responsibility for child welfare. Each pressed claims to administer a variety of institutions entrusted with aiding abandoned juveniles.[7] At first, early in 1918, decrees specified that care of homeless youths (including the operation of children’s homes) belonged in the Commissariat of Social Security’s hands.[8] But Narkompros, undaunted, continued to lobby Sovnarkom for a greater share of responsibility in this area and gradually prevailed. As early as June 1918, Sovnarkom ordered the transfer to Narkompros of institutions for delinquents, and the following month Narkompros sent circulars to provincial agencies, instructing them to turn over Juvenile Affairs Commissions (which handled the cases of delinquents) to Narkompros offices on the scene. Unimpressed by these instructions, some local branches of the Commissariat of Social Security refused to relinquish control, and the matter lay unresolved for months. As a result, from province to province, one found commissions run by each of the two commissariats and even, in a few instances, by the Commissariat of Health.[9] Finally, in February 1919, Sovnarkom ordered the Commissariat of Social Security to transfer its remaining children’s institutions to Narkompros by year’s end, thereby terminating the former’s brief tenure in the vanguard of the campaign to rescue street urchins.[10]

Narkompros also bickered with the Commissariat of Health, for each claimed a larger role in the care of indigent children than the other deemed appropriate.[11] Champions of Narkompros naturally stressed the importance of providing a proper education and general upbringing, while health officials emphasized the need for medical care. Beset by these competing appeals, Sovnarkom issued a series of decrees beginning in the autumn of 1919, spelling out the domain of each agency. In general, the Commissariat of Health retained control of children’s clinics, sanatoriums, and similar institutions where medical treatment and physical therapy represented the principal activity, while pedagogic facilities remained under the administration of Narkompros. According to a decree issued by Sovnarkom in September 1921, doctors chosen and paid by the Commissariat of Health would provide medical treatment for youths in Narkompros’s establishments. At the same time, local Narkompros branches received the right to nominate candidates for these positions and to dismiss individual physicians.[12] Jurisdictional rivalries flared now and then during the remainder of the decade, but they were not so severe as to prevent the two agencies from reaching an accommodation. Health officials operated homes for juveniles up to age three (as well as medical facilities for older youths), and Narkompros administered institutions for residents three years of age and older.[13]

Thus Narkompros emerged with primary responsibility for the rehabilitation of street children. By the beginning of 1923, after a series of internal reorganizations, the agency had evolved the following departments and subsections to undertake the mission: At the highest level, in Moscow, the commissariat’s branches (covering such bailiwicks as publishing, the fine arts, censorship, propaganda, higher education, and vocational training) included one titled Main Administration of Social Upbringing and Polytechnic Education of Children (Glavsotsvos). Glavsotsvos in turn contained a number of subsections with responsibilities that included preschool and primary school education, teacher training, and experimental educational institutions. The subsection of central importance in the attempt to reclaim abandoned youths bore the name Social and Legal Protection of Minors (SPON).[14]

SPON’s four subdivisions focused their attention respectively on (1) the struggle against juvenile homelessness and delinquency; (2) the establishment of guardianships for youths; (3) the rearing of “defective” children (which included delinquents); and (4) the provision of legal assistance and information of benefit to juveniles (such as locating lost dependents and reuniting them with relatives). SPON thus administered most of Narkompros’s orphanages, supervised its Juvenile Affairs Commissions, and dispatched social workers to approach young inhabitants of the street.[15] Throughout the Russian Republic, each province maintained its own Narkompros office (GubONO), generally organized to resemble the basic blueprint of Narkompros in Moscow. Among the branches of a GubONO, therefore, one customarily found a Gubsotsvos (the provincial equivalent of Glavsotsvos) with its own SPON subsection shouldering assignments similar to those of SPON in Moscow. Even smaller administrative units, such as districts (uezdy) and cities, sometimes opened their own Narkompros offices, which commonly retained a structure close to that described above.[16] In Moscow, the thousands of tattered youths thronging the capital by 1922 prompted formation of an Extraordinary Commission in the Struggle with Juvenile Besprizornost’ and Juvenile Crime (the Children’s Extraordinary Commission, for short)—a division of the Moscow City Narkompros organization (MONO). Thereafter the Children’s Extraordinary Commission sought out Moscow’s homeless, handled cases of juvenile delinquents, and administered welfare institutions until it was combined at the beginning of 1925 with another unit of MONO to produce a new division bearing the SPON title.[17]

In January 1919, amid the commissariats’ wrangling, Sovnarkom decreed the formation of a Council for the Defense of Children. Headed by a representative from Narkompros and including members from the commissariats of labor, food, social security, and health, the council received instructions to coordinate the work of individual government agencies to improve the supply of food and other essentials to juveniles.[18] However, as it lacked the leverage to command respect from even the commissariats represented in its own offices, the council made little headway promoting bureaucratic cooperation and played an insignificant role in providing relief to destitute youths.[19] Before long, it gave way to a more imposing interagency body, a commission driven initially by the zeal and clout of the secret police.

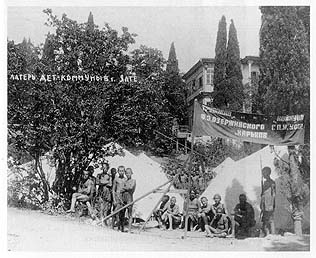

To some, the name Feliks Dzerzhinskii, head of the Cheka (secret police), suggested dry-eyed ruthlessness—an image that Dzerzhinskii himself scarcely shunned. But when conversation turned to the plight of waifs, his expressions of dismay at their misery struck more than one interlocutor.[20] In just such a conversation he told Anatolii Lunacharskii, head of Narkompros:

Pursuing this goal, Dzerzhinskii took the lead in establishing, on February 10, 1921, a Commission for the Improvement of Children’s Life attached to the All-Russian Central Executive Committee.[22] Apart from Dzerzhinskii as chairman, the commission included six other representatives, one each from the Cheka, Narkompros, the commissariats of health and food, the Workers’ and Peasants’ Inspectorate, and the Central Trade Union Council. In some respects their duties differed little from those of the earlier Council for the Defense of Children. They were to facilitate the flow of supplies to agencies responsible for juveniles’ welfare and oversee implementation of decrees (as well as suggest new legislation) to protect minors. But the Children’s Commission, more than the council, focused its energy and resources on the problem of homelessness, underscoring the government’s growing concern with this phenomenon. The order creating the council in January 1919 had called for aid to needy youths in general, without referring specifically to those abandoned. Two years later, in February 1921, the All-Russian Central Executive Committee directed the newborn Children’s Commission to assist “first of all” agencies caring for boys and girls of the street.In this matter we must rush directly to help, as if we saw children drowning. Narkompros alone has not the strength to cope. It needs the broad help of all Soviet society. A broad commission under VTsIK [the All-Russian Central Executive Committee]—of course with the closest participation of Narkompros—must be created, including within it all institutions and organizations which may be useful. I have already said something of this to a few people. I would like to stand at the head of that commission, and I want to include the Cheka apparatus directly in the work.[21]

The same decree of February 10 instructed province and district executive committees to designate officials for children’s commissions at these levels in the Russian Republic, and similar organizational structures took shape in other republics. In Ukraine, for example, the equivalent of the Children’s Commission bore the title Central Commission for the Assistance of Children and was attached to the All-Ukrainian Central Executive Committee.[23] The primary role of the commission in the Russian Republic, and of analogous bodies elsewhere, was to assist other government agencies, most notably Narkompros, rather than operate their own orphanages and schools. Nevertheless, Lunacharskii and his lieutenants at Narkompros displayed little enthusiasm for the commission and proposed the creation of interagency bodies featuring a more prominent role for Narkompros and none for the Cheka.[24] But the commission weathered these early challenges (it survived for nearly two decades), and other agencies eventually accepted it as a partner in their labors.

Meanwhile, the number of homeless juveniles steadily increased. As the government struggled to assign general responsibility on this front to such bodies as Narkompros and the Children’s Commission, the question remained: how should they go about aiding millions of beggars and thieves? Everyone desired that prerevolutionary shelters be replaced, but many social workers and educators had no idea—others a bewildering variety of utopian theories—how to organize and operate new institutions.[25] Ilya Ehrenburg described the chaos that reigned among facilities for “morally defective” youths in Kiev during the months of Bolshevik control in 1919. Though he possessed no experience or even any connection with such work—and thus much to his surprise—he received an assignment to help rehabilitate children.

We spent a long time working out a project for an “experimental pilot colony” where juvenile law-breakers would be educated in a spirit of “creative work” and “all-round development.” It was a great time for projects. In every institution in Kiev, it seemed, grey-haired eccentrics and young enthusiasts were drafting projects for a heavenly life on earth. We discussed the effect of excessively bright colours on excessively nervous children and wondered whether choral declamation influenced the collective consciousness and whether eurhythmics could be helpful in the suppression of juvenile prostitution.

The discrepancy between our discussions and reality was staggering. I began investigating reform schools, orphanages and dosshouses where the besprizornye (lost children) were to be found. The reports I drafted spoke not of eurhythmics but of bread and cloth. The boys ran away to join various “Fathers”; the girls solicited prisoners of war returning from Germany.[26]

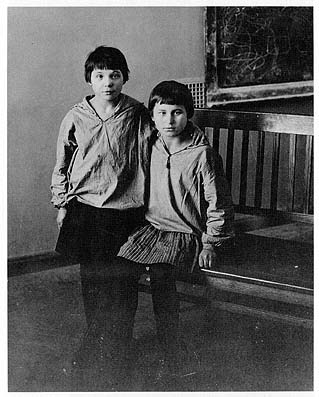

The approach developed at Narkompros by the early 1920s called for three stages of institutions: one to remove a child from the street and tend to his or her immediate needs; a second to observe and evaluate the youth; and a third to achieve rehabilitation. Closest to the street in this system were the receivers (priemniki), facilities generally administered by SPON personnel and often located near markets, train stations, and other settings frequented by the homeless.[27] Narkompros planned for receivers in all cities and towns down to the district level and intended that they admit waifs twenty-four hours a day for emergency shelter, care, and questioning.[28] In addition to youths who arrived on their own, receivers were to accept children dispatched by social workers, the police, and private citizens. This included juveniles apprehended for begging, prostitution, street trade, and thefts, as well as those who appeared to have lost contact with their parents only temporarily. In the case of delinquents, Narkompros hoped that receivers would provide a less pernicious environment than police-station cells and issued instructions in 1920 that staff members greet all entrants with warm attention.[29]

Upon arrival, a youth was to be questioned (in an effort to establish identity, recent activities, place of residence, reason for entering the facility, and so on), then taken to receive a bath, haircut, medical exam, and disinfected clothes, followed by isolation for those with infectious diseases. Narkompros intended that children remain in receivers no more than two or three days and therefore did not foresee extensive pedagogic activity at this stage—nothing more than exercise, crafts, singing, readings by the staff, domestic chores, and attempts to nurture better personal hygiene.[30] The plan stipulated that inhabitants be sorted and housed separately according to age, sex, and other characteristics to prevent contact between a practiced young criminal, for instance, and a lad new to the street.[31] Finally, after a few days of observation, a child faced discharge to a destination deemed appropriate by the staff. This might be to parents or relatives if they could be located, to a Juvenile Affairs Commission in most cases involving crimes, to a children’s home to begin rehabilitation, to a hospital, or to an intermediary institution for additional observation.[32]

The last option routed a child to an “observation-distribution point.” Here ensued an extended period of examination designed to establish the subject’s mental and physical condition—and thus the type of institution likely to provide suitable upbringing. Narkompros considered observation-distribution points particularly appropriate for difficult or troubled youths and intended that information assembled at this stage be passed on to assist Juvenile Affairs Commissions in deciding the means of rehabilitation for delinquents.[33] According to a circular prepared by a division of SPON in Moscow, the normal length of stay in an observation-distribution point was to range from one to three months, though it could reach “six months or more” if necessary. Under these conditions, regular school classes still made little sense, but SPON recommended that some form of rudimentary instruction take place—making a start toward literacy, for example—in addition to the sorts of activities suggested for a receiver.[34] Given the resources and staff required to maintain observation-distribution points, Narkompros must have expected them only in large cities, a pattern of concentration that soon developed in any case.[35] As the years passed, so few such facilities appeared that the vast majority of Narkompros’s wards never entered their doors, moving instead from receivers (or the street) directly to institutions of rehabilitation.

Lunacharskii’s commissariat intended the children’s home (detskii dom, often shortened to detdom, pl. detdoma) to be the most common site of extended rehabilitation. A model charter for detdoma sent by Narkompros in 1921 to its provincial branches presumed an extensive array of these institutions—some for preschool candidates, some for older youths, some for delinquents, some for the physically handicapped, and so on.[36] Narkompros emphasized repeatedly that the network’s success hinged on detdoma admitting only children who had already undergone preliminary sorting in a receiver and, ideally, an observation-distribution point. In addition, detdoma were to conduct periodic evaluations of their residents’ mental and physical health so that those with problems rendering them unsuitable for a particular detdom could be identified and sent to a more appropriate institution or to an observation-distribution point for further appraisal.[37]

As spelled out in the charter, a model detdom maintained the following facilities: ample sleeping quarters, kitchen, dining room, laundry, bath, storerooms, quarantine, separate rooms for the staff, rooms for special projects, and a few workshops for activities such as carpentry, leather work, and sewing. Narkompros also desired the children to receive a standard education, either inside the detdom or at a nearby public school. To supplement traditional classroom instruction and fill free time productively, detdoma received strong encouragement to organize clubs and circles. Suggested activities included drama, music, handicrafts, sports, animal and plant raising, investigations of nature in the surrounding area, and studies of local folklore.[38] In addition, every detdom was to have at its disposal sufficient land for a kitchen garden and, if possible, a larger field to provide food and labor training for the inhabitants. An order from Narkompros and the Commissariat of Land in December 1923 specified that a detdom receive approximately one-quarter of an acre per child.[39] Finally, institutions were urged to implement a program of “self-service” or “self-government” (samoobsluzhivanie or samoupravlenie), which, broadly speaking, meant that youths assumed responsibility for daily chores and some administrative decisions.[40] Such measures, designed to imbue residents with a sense of control over their lives and an instinct for collective responsibility, were destined to receive considerable attention in years to come.

While the government anticipated that most homeless children would follow the path just described, from receiver to detdom, it made additional provisions for youths charged with crimes. Shortly after the Revolution, in January 1918, Sovnarkom and the Commissariat of Justice directed that juvenile delinquents not appear before courts or receive prison sentences. Instead, the decree ordered the formation of Juvenile Affairs Commissions to handle cases of all offenders less than seventeen years of age.[41] Originally placed under the Commissariat of Social Security, but transferred to Narkompros in 1920, each commission comprised three members from local offices of Narkompros and the commissariats of health and justice, with the first serving as head.[42] Soviet authors proclaimed at the time (some noting the contrast with the treatment of delinquents in tsarist Russia and Western countries) that youths would now be rehabilitated, not punished.[43] At the beginning of the 1920s, plans called for commissions in virtually every city down to the level of district towns, a network as dense as that envisioned for receivers. Indeed, Narkompros intended the closest cooperation between commissions and receivers, with the latter (or observation-distribution points, where these existed) holding delinquents temporarily and providing commissions with information on their mental and physical condition.[44]

Commissions were instructed to conclude cases by selecting one of numerous options, among them a simple conversation or reprimand, the dispatch of children to parents or relatives (if these could be located and appeared capable of providing a satisfactory upbringing), or placement in a job, school, detdom, or medical facility. By 1920, however, instructions recognized that such measures might not be appropriate for inveterate young criminals (who were proliferating along with homeless adolescents in general) and therefore granted commissions the choice of passing particularly difficult offenders on to the courts.[45] In March, Sovnarkom increased by one year the maximum age of juveniles whose cases were to be handled by commissions—but at the same time allowed these bodies to transfer intractable youths at least fourteen years old to the courts. Because such decisions required the establishment of a child’s age, often difficult under the circumstances, additional directives advised commissions to rely, if necessary, on estimates derived from medical examinations. The Commissariat of Justice received orders to hold teenage defendants apart from adult criminals in all stages of the judicial process and place those sentenced by the courts in special reformatories.[46]

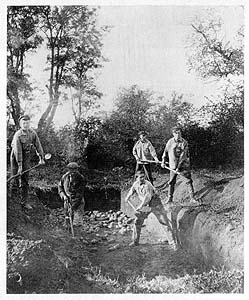

When commissions (as opposed to the courts) channeled delinquents into institutions, the destination was generally a facility operated by Narkompros. Here and there around the country, officials inaugurated establishments bearing a variety of names—detdoma, colonies, communes, institutes—intended exclusively for a “difficult” or “morally defective” clientele. Narkompros issued detailed instructions for the proper operation of these institutions, accompanied by articles in its journals stressing the wisdom (and economy) of reclaiming youths before crime became their adult profession.[47] According to reports and resolutions at the First All-Russian Congress of Participants in the Struggle with Juvenile Defectiveness, Besprizornost’, and Crime (held in the summer of 1920 in Moscow) and instructions issued later by Narkompros, facilities for difficult children were to resemble regular detdoma in many respects. Officials stressed, for example, that an institution contain residents of the same sex, age, and level of development (or degradation). Also, activities in schools, clubs, and workshops had to fill the inhabitants’ lives, eliminating unsupervised idleness. In particular, guidelines emphasized labor training, whether on the land or in workshops, as essential in nurturing desirable work habits and good character—besides preparing trainees to help build a new society.[48]

At the same time, Narkompros’s resolutions and instructions indicated a number of ways in which institutions for delinquents should differ from ordinary detdoma. Discipline, for instance, had to be stricter, though never vindictive. If a violation of the rules seemed to warrant sanction stiffer than a reprimand, additional punishments could include extra chores, temporary deprivation of recreation and other pleasures, or even isolation in a separate room (under staff supervision). Corporal punishment was not permitted.[49] Narkompros also advised that facilities for difficult children operate on the principle of “closed doors” (zakrytyedveri), meaning that instruction take place on the premises and youths not be permitted to leave the grounds on their own.[50] Institutions themselves belonged mainly in the countryside, far removed from temptations afforded by train stations, markets, and other bustling urban sites.[51]

Commissariats other than Narkompros (and the Commissariat of Health) also administered facilities for delinquents—in particular, for teenagers whose cases Juvenile Affairs Commissions had transferred to the courts. Once before a court, a youthful offender faced sentence to a labor home (trudovoi dom) run by the Commissariat of Justice until 1922, and through the rest of the decade by the Commissariat of Internal Affairs.[52] Activities favored here resembled those expected in Narkompros’s detdoma for difficult children—school, workshops, agriculture, sports, even a form of “self-government”—but with still more emphasis on rehabilitation through labor.[53] Guidelines for operating labor homes appeared in the Russian Republic’s Correctional Labor Code rather than Narkompros’s publications. Also, while labor homes shared many of the pedagogic methods of detdoma, they were to employ stricter discipline together with window bars and guards to restrain their charges.[54] As in other “institutions for the deprivation of freedom,” those assigned to labor homes served sentences, which a court could extend to an inmate’s twentieth birthday.[55]

This, in broad strokes, completed the array of facilities intended at the beginning of the 1920s for most abandoned and other abused or delinquent children. To guide them into such institutions, Narkompros set about deploying a corps of social workers. In September 1921, Sovnarkom ordered the formation of a Children’s Social Inspection, under the administration of Narkompros, to spearhead the battle against juvenile homelessness, delinquency, begging, prostitution, and speculation (a term often applied to street trade). The inspectors were intended to replace the police in most dealings with minors, and their duties included patrolling markets, stations, and other locations that attracted waifs. They could call on the police for assistance but did not carry weapons or wear uniforms themselves. Narkompros hoped they would manage to establish contact with youths, draw them out of places exercising an unhealthy influence, and direct those lacking homes to receivers.[56]

The doorstep of a receiver or Juvenile Affairs Commission did not mark the end of the Social Inspection’s beat. Sovnarkom noted in its September decree that inspectors’ duties included supervising youths admitted to receivers (or observation-distribution points) and assisting in their examination. Both receivers and commissions, as interested parties, held the right to submit candidates for positions in the Social Inspection.[57] Commissions themselves were to rely first on another set of social workers, known as investigators-upbringers (obsledovateli-vospitateli), for the following assistance: (1) investigation of offenders (their backgrounds, personalities, and crimes) scheduled to appear before commissions; (2) presentation of this information in commission hearings; and (3) implementation of decisions reached by commissions (supervising guardianship arrangements, for example, or escorting youths to institutions). The general similarity between the duties of the Children’s Social Inspection and investigators-upbringers allowed commissions to call on the former for assistance in the absence of the latter.[58]

| • | • | • |

This was the plan. Almost at once, however, the problem’s breadth overwhelmed officials and the institutions just described. Even during the period from 1918 to early 1921—before the Volga famine confronted the state with additional millions of starving refugees—youths roamed the country in numbers far exceeding the government’s capacity to respond. At this time, investigations of children’s institutions around the country revealed that shortages of food, clothing, buildings, equipment, and staff not only complicated the opening of new facilities but prevented many already in existence from meeting their charges’ most basic material needs (to say nothing of education and rehabilitation). Nearly the entire population, after all, suffered privation during the gaunt years of War Communism, and detdoma bore no immunity to these hardships.[59] Conditions in some institutions appeared as deplorable as life on the street and left officials uncertain whether to continue packing urchins inside.[60] Despite instructions from Moscow that no effort be spared to supply orphanages (and, at a minimum, to distribute food to hungry youths left outside), stern commands could not alter the stark reality of pervasive shortage.[61]

Throughout the Civil War, the army naturally consumed a sizable portion of the government’s meager resources, including materials previously earmarked for children’s institutions. In many regions military authorities commandeered buildings in use or intended as juvenile facilities—and sometimes proved reluctant to surrender the structures to Narkompros or the Commissariat of Health after hostilities had ceased.[62] Government agencies besides the army, facing the same shortage of serviceable buildings, appropriated detdoma while shrugging away protests from provincial children’s commissions and Narkompros. Ironically, given Dzerzhinskii’s leading role in the Children’s Commission, a report from Irkutsk told of the local Cheka requisitioning such an institution during the Civil War and refusing to relinquish it after the Bolsheviks’ triumph. These difficulties left Narkompros (and the Commissariat of Social Security earlier) to enlist many substandard structures in the expanding network of detdoma.[63]

The torrent of waifs loosed by the Volga famine thus descended upon a makeshift network of receivers and detdoma already swollen with victims of previous catastrophes. From the summer of 1921 well into 1922, Narkompros offices across broad stretches of the starving heartland found themselves besieged daily by dozens and even hundreds of juveniles clamoring for admission to detdoma. Some beleaguered officials could scarcely stir in their own buildings, so clogged were the halls with children who had often been waiting weeks for assignment to the orphanages. Parents, too, joined this throng and thrust forth offspring they could no longer feed. Desperate appeals from provincial agencies to Moscow grew routine—and could not be satisfied, as the calamity’s scope dwarfed resources at hand.[64]

Throughout the famine territory, and in many nearby provinces, children swamped detdoma even after officials had scrambled to open additional institutions in every conceivable structure. For each building pressed into service, thousands of homeless youths remained on the street. A Narkompros office in Simbirsk province accepted only candidates facing imminent death, so overcrowded were the facilities.[65] To ease institutions’ congestion, Narkompros branches around the country ordered the discharge of low-priority inhabitants whose parents or relatives could be located.[66] Many residents shown the door had been placed in detdoma by parents pleading inadequate family resources or (less often) a desire that their sons and daughters receive a collectivist upbringing. Some were progeny of the institutions’ own staffs. In a number of regions, local officials transferred adolescents from detdoma into the care of peasant families. By no means all peasants selected had volunteered—with the predictable result that “their” new children often fared poorly and soon fled to the street.[67] Narkompros hoped, of course, that these measures would free more places in detdoma for the genuinely homeless, which they did. But those inside the walls of institutions still represented a small fraction of the crowds on their own.

The introduction of the New Economic Policy during 1921 presented administrators of children’s institutions with another set of problems. NEP forced many state enterprises and provincial government agencies to assume greater responsibility for their own finances. Unable to rely any longer on Moscow for more than a fraction of their budgets, and finding other government bodies in similar straits now unwilling to supply necessities free of charge, local Narkompros officials moved to close some detdoma in order to reduce expenses. By 1922–1923 they had done so in substantial numbers.[68] The children involved were squeezed into other detdoma, placed in families of the surrounding population, or left to fend for themselves. Whatever the economic advantages of NEP’s “market discipline,” they were difficult to ascertain at once from the vantage point of orphanages.

A decade later, looking back over her years of work with abandoned youths, Asya Kalinina recalled that in 1922 the task appeared nearly hopeless. She and her colleagues feared then that juvenile homelessness and delinquency, which were assuming ever more dire proportions, might eventually corrode the foundation of the Soviet state.[69] The briefest tour of famine provinces erased any thought that the boarding institutions of Narkompros and other agencies might perform as planned. How could anyone press ambitious programs for rehabilitation and upbringing on facilities buried in wraithlike children? Yet something had to be done.

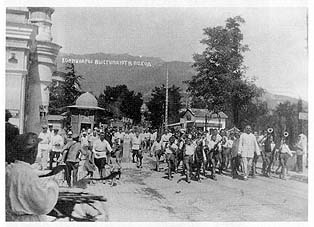

As early as the summer of 1921, the number of people threatened with starvation had reached a scale sufficient to trigger planning for a variety of emergency measures, none more dramatic than mass evacuations of juveniles from afflicted provinces. The Children’s Commission, Narkompros, and other bodies formed special divisions for the project, with Narkompros’s Evacuation Bureau (whose members included representatives from several agencies) most directly involved in its implementation.[70] Officials in comparatively prosperous regions received telegrams instructing them to inform Moscow how many Volga youths they could accept, while evacuation procedures were devised to guide authorities in the famine zone. The ambitious plan for September–October 1921 called for removing approximately 40,000 boys and girls.[71] Not surprisingly, as soon as the policy of evacuation appeared on the government’s list of options, officials in ravaged districts showered Moscow with communications emphasizing the distress in their areas and pleading that thousands of juveniles be transported to other parts of the country. Well before year’s end the number claimed to require evacuation approached 175,000—exceeding by nearly 100,000 the total that other sections of the country agreed to support.[72] Authorities in some stricken cities abandoned all restraint and placed candidates—in a few cases, the entire populations of detdoma—on trains headed out of the region, without waiting for Moscow’s permission.[73]

Altogether, from June 1921 to September 1922, the government evacuated approximately 150,000 children. A majority appear to have been orphans or otherwise homeless, though information is far from complete. Nearly all came from seven provinces (Samara, Saratov, Simbirsk, Ural, Ufa, Cheliabinsk, and Tsaritsyn), three Autonomous Republics (Tatar, Kirghiz, and Bashkir), and several smaller Autonomous Regions (those of the Volga Germans and Chuvash among them). Saratov and Samara provinces alone each supplied over 25,000, and the Kirghiz Republic over 20,000, in scarcely more than one year.[74] Destinations lay in every direction from the Volga basin and included Siberia (notably Omsk and Semipalatinsk), Central Asia (Samarkand, Bukhara, and Tashkent), the Transcaucasian republics, Ukraine (mainly the provinces of Podol’sk, Kiev, Poltava, Volynsk, and Chernigov), and Petrograd. Many other cities (and their surrounding districts) also received contingents numbering in the thousands, including Vitebsk, Novgorod, Pskov, Smolensk, Gomel’, Kursk, Nizhnii Novgorod, Orel, Tula, Iaroslavl’, and Tver’.[75] Published plans did not designate an especially large share for Moscow, possibly because young refugees arriving on their own had already inundated the city. Finally, in the fall of 1921, the Children’s Commission even approved projects for evacuating juveniles to Czechoslovakia, Germany, and England. The documents do not indicate whether any ever set out for Germany and England, but agreement was reached with Czechoslovakia on the evacuation of 600 children, at least 486 of whom arrived.[76]

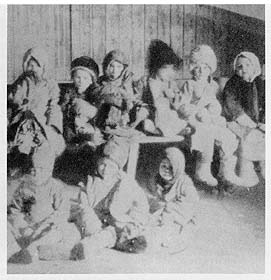

While several thousand youths made their journeys by boat, commonly sailing up the Volga to Nizhnii Novgorod, well over 90 percent traveled by train.[77] Special “sanitary trains” (sanpoezda) often carried from 400 to 600 children, and one hauled 983.[78] Juveniles selected for these trips were to receive haircuts, baths, and disinfected clothes, along with a clean bill of health. Indeed, no one qualified for evacuation from a detdom if cases of any severely contagious disease had been detected at the facility during the previous two weeks. Those living outside institutions faced a two-week quarantine before departure.[79] As it turned out, in areas where the starving population lived far from rail lines, youths did not always assemble at stations in accordance with Moscow’s timetable. Authorities in Saratov, for example, received instructions initially to load each arriving train only with residents of one district or another. When the intended passengers did not materialize in Saratov on time, trains had to wait, thus disrupting the evacuation schedule. Before long, new orders permitted officials to fill trains with any candidates available.[80]

Conditions on board varied considerably. Some trains were clean and warm, with ample food, medical attention, and dedicated personnel.[81] Others left a different impression. Trains deployed to pick up children were supposed to contain supplies of food, clean clothing, and bedding, but many clattered into town empty and filthy. A telegram from the Samara Children’s Commission to Moscow complained on one occasion that officials had to strip clothing from juveniles left behind in order to outfit those departing. In Saratov, a local journal revealed that train crews stole shoes and clothing sent for evacuees and sold the items in bazaars. Once a trip had begun, shortages of food sometimes prompted the young passengers to slip out at stops to forage for provisions. Delays at stations could stretch on for days—as when depot authorities unhitched the trains’ engines for other tasks or refused to provide fuel and similarly vital supplies. Meanwhile, poor sanitation produced illness and death. In fact, officials among the Volga Germans, after evacuating a few trainloads of the region’s offspring, resolved to send out no more. Such wretched conditions obtained aboard the trains, they concluded, that youths possessed a better chance of surviving in the famine region itself.[82]

The most vociferous complaints sounded outside the famine territory—from authorities who received the deliveries. Time and again they bombarded the Children’s Commission and Narkompros in Moscow with indignant reports of trains unloading boys and girls clad only in undershirts or similarly inadequate apparel. According to a Narkompros official in Poltava, “all of the children who arrived were, without exception, absolutely naked and barefoot.” The Ukrainian Central Commission of Aid to the Starving protested repeatedly to the Russian Republic’s Narkompros that youths evacuated from the Volga provinces to Ukraine had not been given adequate clothing for their journey. This violated Moscow’s own instructions on evacuation, the Ukrainians reminded Narkompros, adding that they could not themselves supply all the arrivals with clothes.[83] Worse still, dispatches from many cities described disease as commonplace among evacuees, an indication of disregard in the famine zone for the two-week quarantine rule. Of the 578 juveniles delivered by a single “sanitary train” to Vladimir, “over 100” had to spend the first few weeks in hospitals with cases of typhus, measles, and smallpox. Narkompros’s office in Novgorod reported in December 1921 to the Evacuation Bureau in Moscow that “many” on the most recent train from the Volga were sick—and a “few” dead. A health official in Novgorod telegraphed to Moscow that trains from famine provinces had saturated local hospitals with typhus cases, exhausting resources available to treat them and threatening the entire region with infection.[84]

Instructions from Moscow specified that children evacuated from famine districts be housed, upon reaching their destinations, in special facilities (such as a converted receiver, detdom, or clinic) for a two-week period of medical examination and quarantine. Youths routed to Smolensk province, for example, traveled initially to the town of Roslavl’, where they stayed in a set of old barracks for medical processing. Only then were they deemed fit for transfer to more permanent accommodations.[85] More often than not around the country this meant detdoma—supported in part by trade unions, factories, military units, institutes, newspapers, cooperatives, and the Cheka. Even the involvement of these organizations did not provide sufficient resources to sustain all famine refugees, however, and officials turned to placing some children in local peasant families.[86]

Regions struggling to absorb evacuees found the task complicated by still more boys and girls, at least 100,000 strong, arriving from the famine zone on their own.[87] In December 1921 and January 1922, for instance, the Kuban–Black Sea province received 200 youths in “organized fashion” from famine districts and another 3,400 whose travel arrangements appeared in no government plans. Thousands of miles to the east, in Siberia’s Eniseisk province, 967 children arrived through official channels between March and November 1922, while 280 made the journey themselves.[88] Some authorities in the Northern Caucasus and Georgia, areas that attracted many refugees, attempted to seal their borders by stationing detachments there to repulse anyone traveling without “legitimate” purpose.[89] Though the success of these measures is questionable, their extraordinary nature testifies to the difficulties that those fleeing the famine caused administrators of territories they entered.

The seemingly endless stream of refugees, “organized” and otherwise, combined with the central government’s inability to provide anything approaching the resources necessary to support them, soon moved provincial officials to appeal that Moscow route no more shipments their way. On occasion these entreaties included threats to turn any future trains around and send them, still loaded, out of the region. A few district authorities eventually did refuse to unload evacuation trains and dispatched them down the line to other towns—which in turn sometimes passed them on further.[90] While open defiance did not constitute the norm, the provinces made no secret of their impatience for permission to reevacuate those who bulged their detdoma and exhausted their resources. By the middle of 1922, with a better harvest anticipated in the Volga basin, Moscow heeded such complaints and began the process of sending refugees home.[91]

According to guidelines developed in the capital, officials were authorized to reevacuate minors only after obtaining written confirmation of parents’ consent and only if the children received shoes, clothing, food, and train tickets.[92] It often proved next to impossible, however, to locate mothers and fathers hundreds of miles away and document their agreement for the return of offspring. During the famine, parents themselves traveled far and wide as refugees, and many had left this world altogether. In response, local authorities began sending juveniles back to home regions—or any other available province—without authorization from Moscow and without observing the guidelines they received. Eager to reduce the financial strain imposed on them by thousands of evacuees, they shipped them home, observed a Narkompros report, “allegedly to their parents, who almost never, incidentally, turn out to be alive.” Approximately 25 percent of the youths reevacuated to the Tatar and Bashkir republics fit this description, and close to 30 percent of those transported “home” to Saratov and Samara provinces found neither parents nor relatives on their arrival. They either crowded into receivers and detdoma just as overtaxed as those they had departed or hunted for shelter in alleys and train stations.[93]

Among the children reevacuated into a void were the boy and his sister, Anna, who had dragged their younger sister, Vavara, along the road to Kazan’ on Christmas Day of 1921. After Vavara succumbed to typhus, the children’s parents and elder sister arrived in Kazan’ and found room in other shelters; thus family members were reunited in the same city if not the same building. But as each week of famine left the region ever more desperate, officials decided to evacuate the two youngest children (and many others) by rail to Ukraine. At the end of a month’s journey, the special train reached Vinnitsa, where local authorities, already swamped with starving youths, turned it away. The train itself became something of a besprizornyi, rumbling down the tracks to the town of Mogilev-Podol’skii on the Romanian border. Here the passengers’ fortunes improved. They landed in a children’s home that provided not only ample food but also schooling and other activities. Several months later, after the famine had abated, the youths were reevacuated to Kazan’. Anna and her brother discovered no trace of their parents and could do nothing but enter a foul shelter for indigents. The conditions soon prompted them to leave Kazan’, bound initially for their native Grodnensk province (by then part of Poland), but destined instead for separate children’s homes in Moscow.[94]

For years the government struggled to reassemble such families. Even before the famine scattered its victims across the country, parents and relatives approached officials regularly for help in determining the whereabouts of progeny lost during World War I and the Civil War. Toward the end of 1921, Narkompros organized a Central Children’s Address Bureau to collect information on institutionalized juveniles for use in responding to these inquiries—which multiplied in the aftermath of the Volga basin evacuation.[95] The Address Bureau did manage to locate some youths sought by relatives (582 in 1923/24), but the numbers never exceeded a small fraction of those who had disappeared.[96] Such modest results prompted Narkompros and the Children’s Commission to approach local officials and the public more directly by publishing lists of vanished offspring. These rosters appeared now and then in various periodicals by the middle of the decade and commonly included the names and ages of dozens or even a few hundred youths missing from one region or another. On occasion, the inventories produced responses that reunited families, but not at a rate sufficient to trim the homeless population perceptibly. The lists that Narkompros placed in its weekly bulletin, for example, succeeded in uncovering only four lost children.[97]

Why were tens of thousands of sons and daughters, even those transported from famine districts by the government itself, so difficult to find as conditions slowly improved after 1922? No doubt many parents whose children had embarked on “sanitary trains” shared this perplexity. Much of the frustration stemmed from the evacuation’s chaotic nature. Four copies of a form (containing such information as the child’s name, location of original family home, and addresses of the dispatching and receiving institutions) were to be prepared for each boy or girl shipped out of the famine zone. But all too often the records were transcribed inaccurately, lost, or not compiled in the first place. Haste and sloppiness in these desperate times corrupted data to the point where someone searching for, say, Anastasiia Shcherbakova, and finding on the list an Anastasiia Shcherbaniuk, had grounds to wonder whether the two names identified the same girl. More likely, the object of an inquiry failed to appear in government registers at all. According to an article published in 1928, the list of evacuated minors composed by the middle of the decade contained only about thirty thousand names. Even when records were filed properly, subsequent undocumented transfers of juveniles to peasant families or from one institution to another rendered the original paperwork obsolete—as did the flight of youths from foster homes and detdoma.[98] Many children obscured their tracks by entering relief facilities under fictitious names. Wily vagrants, with no desire for a trip home, proffered aliases with polished ease. Others, especially the very young, who could not remember their identities, received names (and even nationalities) arbitrarily from officials. Revolutionary heroes numbered among the sources of inspiration for these choices—leaving some orphanages stocked with such ersatz celebrities as Klara Tsetkin, Inessa Armand, Mikhail Kalinin, and Sof’ia Perovskaia.[99]

| • | • | • |

As early as 1921, an occasional voice questioned the mass evacuations then in progress, arguing that the exercises wasted government relief funds and even harmed some of the children involved. A teacher traveling in 1921 with a train transporting youths from Saratov to Vitebsk contended that this method rescued only an insignificant percentage of those starving, far fewer than could be saved by allocating equivalent resources to the blighted provinces themselves.[100] If such objections did not sway Narkompros initially, problems beleaguering the evacuation and reevacuation campaigns convinced the government by 1923 to abandon these large-scale endeavors. In 1924, the All-Russian Central Executive Committee ordered a halt to mass transfers of children. Individuals might still be reevacuated, if parents or relatives awaited them and possessed means to provide proper care. Otherwise, juveniles qualified for transfer only by consent of the Narkompros office in the province of their destination. When partial crop failure returned to several Volga provinces in 1924, Narkompros rejected another round of mass evacuations and concentrated instead on directing aid to the stricken districts.[101]

Whatever the wisdom of evacuation in 1921–1922, the policy sprang from the sound conclusion that receivers, detdoma, and clinics in the region could not begin to cope with the prostrate multitudes. This same realization prompted the opening of food distribution points in the famine zone, as a socialist upbringing for residents of detdoma yielded to efforts aimed at keeping the starving alive wherever they huddled. To this end, the government established cafeterias and dispatched trains to traverse the famine provinces distributing meals and medical care.[102] The public, too, was pressed to donate funds for the emergency. Newspapers carried frequent articles on contributions (doubtless not always as voluntary as described) by soldiers, sailors, workers, and private entrepreneurs to bolster detdoma and provide assistance to other young famine victims.[103] At its peak, aid from individuals, factories, trade unions, military units, and other organizations appears to have maintained at least two hundred thousand juveniles, with trade unions responsible for over half the total.[104]

The government even opened afflicted areas to foreign relief groups.[105] By July 1922, according to Soviet figures for the Volga basin and Crimea (but not Ukraine), foreign organizations were feeding nearly 3.6 million children, with the American Relief Administration (ARA) responsible for slightly over 80 percent of the total. An American account credits the ARA in July with supplying daily nourishment to 3.6 million minors and 5.4 million adults, totals that peaked the following month at 4.2 and 6.3 million respectively. Meanwhile the state distributed food to approximately 1.3 million boys and girls (30,000 by means of the special trains), bringing the number of youths receiving at least occasional meals from these sources close to 5 million.[106] Yet despite this valiant undertaking, millions more went unfed.

The gap between these figures and the enthusiasm fostered by the Revolution for child-rearing projects could not have been greater. As Narkompros put the finishing touches on plans for a network of institutions intended to fashion waifs into a new socialist generation, the famine shifted official priorities to stark survival. Here, obscured by the overwhelming tragedy of the spectacle, resided a forlorn irony. In 1920, as it wrenched primary responsibility from the Commissariat of Social Security for the care of destitute juveniles, Narkompros justified its action by claiming preeminent expertise in educating and rehabilitating youths, as opposed merely to providing for their material well-being. But when Lunacharskii’s commissariat finally turned to the mission it had won, officials found themselves facing conditions that rendered education and rehabilitation all but impossible. The new generation, its members dying by the million, had to be saved before it could be trained.

Notes

1. For a sampling of these decrees, see SU, 1918, no. 68, art. 732; no. 70, art. 768; no. 81, art. 857; SU, 1919, no. 20, art. 238; no. 26, art. 296; no. 47, art. 463. See also L. A. Zhukova, “Deiatel’nost’ Detkomissii VTsIK po okhrane zdorov’ia detei (1921–1938),” Sovetskoe zdravookhranenie, 1978, no. 2: 64; Pravo i zhizn’, 1927, nos. 8–10: 29; Goldman, “The ‘Withering Away’ and the Resurrection,” 88. In some cases the authorized support was earmarked solely for urban areas or for children of working-class families, but even these less sweeping goals far exceeded the meager resources available. On government agencies’ inability to obtain food and clothing for children in anything approaching adequate quantities, see Sheila Fitzpatrick, The Commissariat of Enlightenment: Soviet Organization of Education and the Arts Under Lunacharsky, October 1917–1921 (Cambridge, 1970), 228–229; Liublinskii, Bor’ba, 45.

2. SU, 1921, no. 57, art. 358.

3. Ryndziunskii et al., Pravovoe polozhenie (1927), 96; Kalinina, Desiat’ let, 96, 98; V. Diushen, ed., Piat’ let detskogo gorodka imeni III internatsionala (Moscow, 1924), 5, 28; Vserossiiskoe obsledovanie, 45; Krupskaia, Pedagogicheskie sochineniia 2:158; Pedagogicheskaia entsiklopediia, 3 vols. (Moscow, 1927–1930), 2:354–355.

4. TsGA RSFSR, f. 1575, o. 6, ed. khr. 4, l. 128; Pervyi vserossiiskii sъezd, 3–4, 7, 11–12; Fitzpatrick, Commissariat of Enlightenment, 227–228; Madison, Social Welfare, 36; Krupskaia, Pedagogicheskie sochineniia 3:393; Sotsial’noe vospitanie, 1921, nos. 3–4: 58–62. A few years later, in 1926, Anatolii Lunacharskii told a meeting of personnel from children’s institutions: “If we can overcome our poverty, I would say that the children’s home is the best way of raising children—a genuine socialist upbringing, removing children from the family setting and its petty-bourgeois structure”; see Tizanov et al., Pedagogika, 11. Some proponents of this vision added that children’s homes would emancipate women from child rearing, freeing them to pursue activities outside the home. For more on the “withering away” of the family, see Goldman, “The ‘Withering Away’ and the Resurrection,” 40, 47.

5. N. I. Bukharin and E. A. Preobrazhenskii, The ABC of Communism: A Popular Explanation of the Program of the Communist Party of Russia (Ann Arbor, Mich., 1966), 234. In their chapter on religion, the authors added (p. 253): “One of the most important tasks of the proletarian State is to liberate children from the reactionary influence exercised by their parents. The really radical way of doing this is the social education of the children, carried to its logical conclusion.” The 1918 Family Code prohibited the adoption of children by individual families, revealing the belief of early Soviet jurists that the state would be a better guardian of juveniles. See Goldman, “The ‘Withering Away’ and the Resurrection,” 84.

6. Diushen, Piat’ let, 28; Kalinina, Desiat’ let, 96, 98; Vserossiiskoe obsledovanie, 45.

7. TsGA RSFSR, f. 2306, o. 13, ed. khr. 11, l. 38; Fitzpatrick, Commissariat of Enlightenment, 227; Krasnushkin et al., Nishchenstvo i besprizornost’, 126. The Commissariat of Social Security (Narodnyi komissariat sotsial’nogo obespecheniia) had been called Narodnyi komissariat gosudarstvennogo prizreniia (in some documents, Narodnyi komissariat obshchestvennogo prizreniia) prior to the end of April 1918; see SU, 1918, no. 34, art. 453.

8. SU, 1918, no. 19, art. 287; no. 22, art. 321; Krasnushkin et al., Nishchenstvo i besprizornost’, 126; Detskii dom, comp. B. S. Utevskii (Moscow-Leningrad, 1932), 9.

9. Krasnushkin et al., Nishchenstvo i besprizornost’, 126–127.

10. SU, 1919, no. 25, art. 288; Fitzpatrick, Commissariat of Enlightenment, 227–228; Detskii dom, comp. Utevskii, 4.

11. Krasnaia nov’, 1923, no. 5: 206, 209–210; Margaret Kay Stolee, “ ‘A Generation Capable of Establishing Communism’: Revolutionary Child Rearing in the Soviet Union, 1917–1928” (Ph.D. diss., Duke University, 1982), 52.

12. SU, 1921, no. 65, art. 497. For other illustrations of the division of responsibilities between the Commissariat of Health and Narkompros, see SU, 1919, no. 61, art. 564; Krasnushkin et al., Nishchenstvo i besprizornost’, 126–127.

13. Stolee, “Generation,” 53. For more on abandoned babies, see Sbornik deistvuiushchikh uzakonenii i rasporiazhenii (1929), 94, 99–103; Artamonov, Deti ulitsy, 57; Drug detei, 1927, no. 1: 12; 1928, no. 4: 14–15; Okhrana materinstva i mladenchestva, 1926, no. 12: 28–29; Drug detei(Khar’kov), 1926, no. 2 (this issue contains a number of short articles on abandoned infants).

14. Narodnoe prosveshchenie v R.S.F.S.R. k 1924/25 uchebnomu godu, 3–4; Stolee, “Generation,” 58–59. Roughly similar units took shape in the Narkompros of Ukraine and other non-Russian republics. Regarding the earlier internal reorganizations of Narkompros and the titles of subsections whose responsibilities included the besprizornye, see Kalinina, Desiat’ let, 36; Krasnushkin et al., Nishchenstvo i besprizornost’, 127; Liublinskii, Bor’ba, 183; Detskaia besprizornost’, 4.

15. TsGA RSFSR, f. 1575, o. 6, ed. khr. 156, l. 1; Krasnushkin et al., Nishchenstvo i besprizornost’, 127–129; Detskaia besprizornost’, 4; Liublinskii, Bor’ba , 183–184; Tizanov et al., Detskaia besprizornost’, 171. Along with Glavsotsvos, another unit in Narkompros—the State Scientific Council (Gosudarstvennyi uchenyi sovet)—maintained its own SPON subsection. This particular SPON, rather than working directly with street children, devoted itself mainly to studying the theory and practice of upbringing in an effort to develop methods for rehabilitating besprizornye. See TsGA RSFSR, f. 298, o. 1, ed. khr. 45, ll. 42, 82, 100.

16. TsGA RSFSR, f. 1575, o. 6, ed. khr. 101, l. 3; Besprizornye, comp. O. Kaidanova (Moscow, 1926), 60; Tizanov et al., Detskaia besprizornost’, 130, 170; Narodnoe prosveshchenie v R.S.F.S.R. k 1924/25 uchebnomu godu, 5–6. A similar structure prevailed in areas where the main administrative unit was the oblast’ rather than the guberniia. Before long, most uezd otdely narodnogo obrazovaniia were merged with the uezd-level divisions of various other commissariats into a general otdel of the corresponding uezd Executive Committee.

17. Kalinina, Desiat’ let, 81, 83; Krasnushkin et al., Nishchenstvo i besprizornost’, 143–144; Komsomol’skaia pravda, 1925, no. 27 (June 26), p. 3.

18. SU, 1919, no. 3, art. 32.

19. Vasilevskii, Detskaia “prestupnost’,” 81; Deti posle goloda, 75–76.

20. See for example Kalinina, Desiat’ let, 50; E. Vatova, “Bolshevskaia trudovaia kommuna i ee organizator,” Iunost’, 1966, no. 3: 91. According to Lennard Gerson, “one of the few diversions Dzerzhinsky allowed himself” consisted of frequent drives to visit former besprizornye being raised in a commune sponsored by the secret police. “He once confided to Kursky, the Commissar of Justice: ‘These dirty faces are my best friends. Among them I can find rest. How much talent would have been lost had we not picked them up!’ ”; Gerson, The Secret Police in Lenin’s Russia (Philadelphia, 1976), 127.

21. Quoted in Fitzpatrick, Commissariat of Enlightenment, 230–231. For a Soviet account of this conversation, see Konius, Puti razvitiia, 146–148.

22. SU, 1921, no. 11, art. 75.

23. Regarding the Ukrainian Commission, see Detskoe pravo sovetskikh respublik. Sbornik deistvuiushchego zakonodatel’stva o detiakh, comp. M. P. Krichevskaia and I. I. Kuritskii (Khar’kov, 1927), 18–22; Deti posle goloda, 78–79; Pomoshch’ detiam, 20–21. For instructions from the Children’s Commission in Moscow to its provincial branches, see Records of the Smolensk Oblast’ of the All-Union Communist Party of the Soviet Union, 1917–1941 [hereafter cited as Smolensk Archive], reel 46, WKP 422, p. 299.

24. For these and other unsuccessful challenges to the Children’s Commission, see Fitzpatrick, Commissariat of Enlightenment, 230–236.

25. Kalinina, Desiat’ let, 30–33; Goldman, “The ‘Withering Away’ and the Resurrection,” 83.

26. Ehrenburg, First Years of Revolution, 84.

27. Liublinskii, Bor’ba , 191, 194. The name priemnik was a shortened form of detskii priemnyi punkt (children’s receiving station).

28. Drug detei (Khar’kov), 1925, no. 2: 30; Detskoe pravo, comp. Krichevskaia and Kuritskii, 479–480; Liublinskii, Bor’ba, 191, 193; Detskaia besprizornost’, 36. In some areas, especially Ukraine, these institutions were known as collectors (kollektory).

29. TsGA RSFSR, f. 1575, o. 6, ed. khr. 141, l. 42; Liublinskii, Bor’ba, 191–193; Detskaia besprizornost’, 37; Detskoe pravo, comp. Krichevskaia and Kuritskii, 479.

30. TsGA RSFSR, f. 1575, o. 6, ed. khr. 141, ll. 42–43; Liublinskii, Bor’ba, 193; Detskaia besprizornost’, 37; Detskoe pravo, comp. Krichevskaia and Kuritskii, 479. During the course of the decade, as evident in the archival document just cited and explained in a following chapter, Narkompros increased the period of time that children were to be kept in receivers.

31. SU, 1921, no. 66, art. 506; TsGA RSFSR, f. 1575, o. 6, ed. khr. 141, ll. 42–43; Detskoe pravo, comp. Krichevskaia and Kuritskii, 479, 481; Vestnik narodnogo prosveshcheniia (Saratov), 1921, no. 1: 43.

32. TsGA RSFSR, f. 1575, o. 6, ed. khr. 141, l. 42; Liublinskii, Bor’ba, 194; Detskaia besprizornost’, 38; Detskoe pravo, comp. Krichevskaia and Kuritskii, 479; Min’kovskii, “Osnovnye etapy,” 43.

33. TsGA RSFSR, f. 1575, o. 6, ed. khr. 141, ll. 48, 50–51; Liublinskii, Bor’ba, 194–196. Children presenting unusually complex problems could be sent for diagnosis to even more specialized and well-equipped institutions in major cities.

34. TsGA RSFSR, f. 1575, o. 6, ed. khr. 141, ll. 48–49, 53; Liublinskii, Bor’ba, 194.

35. V. I. Kufaev, “Iz opyta,” 94; Liublinskii, Bor’ba, 194.

36. The charter described a detdom for school-age youths that did not operate its own school; TsGA RSFSR, f. 1575, o. 6, ed. khr. 4, l. 86. See also, regarding different types of detdoma for delinquents, Ryndziunskii and Savinskaia, Pravovoe polozhenie (1923), 55.

37. TsGA RSFSR, f. 1575, o. 6, ed. khr. 156, l. 3; ibid., ed. khr. 4, l. 86.

38. Ibid., ed. khr. 4, ll. 86–87.

39. Ibid., l. 86; SU, 1923, no. 28, art. 326; SU, 1924, no. 23, art. 222.

40. TsGA RSFSR, f. 1575, o. 6, ed. khr. 4, l. 86; Pervyi vserossiiskiisъezd, 7.

41. SU, 1918, no. 16, art. 227; Ryndziunskii and Savinskaia, Pravovoe polozhenie (1923), 54.

42. Prior to March 1920, the commissions were headed by a representative from the Commissariat of Social Security, with the other two members coming from Narkompros and the Commissariat of Justice; SU, 1920, no. 68, art. 308; Ryndziunskii and Savinskaia, Pravovoe polozhenie (1923), 55. Children accused of minor offenses could have their cases resolved in a receiver or a raspredelitel’.

43. See for example V. I. Kufaev, Pedagogicheskie mery bor’by s pravonarusheniiami nesovershennoletnikh (Moscow, 1927), 47; Nesovershennoletnie pravonarushiteli, comp. B. S. Utevskii (Moscow-Leningrad, 1932), 8. Prior to the Revolution, the lowest age for criminal liability had been ten years; see Juviler, “Contradictions,” 263.

44. Vestnik narodnogo prosveshcheniia (Saratov), 1921, no. 1: 43; Liublinskii, Bor’ba, 194; Ryndziunskii and Savinskaia, Detskoe pravo, 250, 253; Vasilevskii, Detskaia “prestupnost’,” 80, 85. The number of commissions actually established lagged far behind the goal.

45. SU, 1920, no. 13, art. 83; no. 68, art. 308; Ryndziunskii et al., Pravovoe polozhenie (1927), 82.

46. SU, 1920, no. 13, art. 83; no. 68, art. 308; Nesovershennoletnie pravonarushiteli, 9–10; Z. A. Astemirov, “Iz istorii razvitiia uchrezhdenii dlia nesovershennoletnikh pravonarushitelei v SSSR,” in Preduprezhdenie prestupnosti nesovershennoletnikh (Moscow, 1965), 255–256. Regarding the handling of juveniles fourteen through seventeen years of age, see SU, 1919, no. 66, art. 590.

47. Astemirov, “Iz istorii,” 256; TsGA RSFSR, f. 1575, o. 10, ed. khr. 177, ll. 1–4, 13–16; Vestnik prosveshcheniia, 1923, no. 2: 66. Commissions could also send youths to institutions operated by the Commissariat of Health, but these were not nearly as numerous.

48. Detskaia defektivnost’, 56, 68; TsGA RSFSR, f. 1575, o. 10, ed. khr. 177, ll. 3–4, 15. These sources also advocated the introduction of “self-government” (samoupravlenie) for “morally defective” youths, but added that the staff should take this step more cautiously than in a regular detdom; see Detskaia defektivnost’, 69; TsGA RSFSR, f. 1575, o. 10, ed. khr. 177, ll. 4, 14.

49. TsGA RSFSR, f. 1575, o. 10, ed. khr. 177, ll. 3–4, 14; Detskaia defektivnost’, 69; Livshits, Sotsial’nye korni, 102.

50. TsGA RSFSR, f. 1575, o. 10, ed. khr. 177, ll. 2, 13; Detskaia defektivnost’, 57, 68–69.

51. TsGA RSFSR, f. 1575, o. 10, ed. khr. 177, l. 2; Detskaia defektivnost’, 35, 56, 69.

52. TsGA RSFSR, f. 1575, o. 10, ed. khr. 177, ll. 6–9; SU, 1924, no. 86, art. 870; Astemirov, “Iz istorii,” 256–257; Ryndziunskii and Savinskaia, Pravovoe polozhenie (1923), 60; Min’kovskii, “Osnovnye etapy,” 46. This did not exhaust the list of institutions to which courts could sentence juveniles. Reformatories (reformatorii), sometimes short-lived, were opened in a handful of places as early as 1918. In at least some instances, they appear to have been intended to house offenders from seventeen to twenty-one years of age, though they also received younger delinquents. In addition, the Correctional Labor Code of the Russian Republic called in 1924 for the establishment, as an alternative to prison, of trudovyedoma specifically for young lawbreakers of worker or peasant background. To qualify, a youth was supposed to be from sixteen to twenty years of age and not carry a record of habitual offenses. See Astemirov, “Iz istorii,” 254–255, 257; SU, 1924, no. 86, art. 870. These institutions were not built in numbers large enough to handle a significant volume of besprizornye.

53. TsGA RSFSR, f. 2306, o. 69, ed. khr. 350, ll. 8–9; SU, 1924, no. 86, art. 870; Ryndziunskii and Savinskaia, Pravovoe polozhenie (1923), 61–62; Sbornik deistvuiushchikh uzakonenii i rasporiazhenii (1929), 124. For a detailed set of guidelines on the operation of labor homes, published a few years later, see Ryndziunskii and Savinskaia, Detskoe pravo, 307–315.

54. Vasilevskii, Detskaia “prestupnost’,” 156; Ryndziunskii and Savinskaia, Pravovoe polozhenie (1923), 61.

55. SU, 1924, no. 86, art. 870; Ryndziunskii and Savinskaia, Pravovoe polozhenie (1923), 62.

56. SU, 1921, no. 66, art. 506; Ryndziunskii et al., Pravovoe polozhenie (1927), 99; Detskaia besprizornost’, 24–25; Liublinskii, Zakonodatel’naia okhrana, 82; Liublinskii, Bor’ba, 184–186; Otchet gorskogo ekonomicheskogo soveshchaniia za period ianvar’–mart 1922 g. (Vladikavkaz, 1922), 255; Pravo i zhizn’, 1925, nos. 4–5: 95–96. In 1926 a new decree and subsequent elaboration from Narkompros spelled out the functions of the Children’s Social Inspection in greater detail. See SU, 1926, no. 32, art. 248; Krasnushkin et al., Nishchenstvo i besprizornost’, 137–138; Tizanov and Epshtein, Gosudarstvo i obshchestvennost’, 27–31. For a description from the Ukrainian Narkompros of the responsibilities intended for its Detskaia inspektsiia (that is, its equivalent of the Children’s Social Inspection), see Detskoe pravo, comp. Krichevskaia and Kuritskii, 443–444.

57. SU, 1921, no. 66, art. 506; Liublinskii, Bor’ba, 184; TsGA RSFSR, f. 1575, o. 6, ed. khr. 141, l. 43.

58. TsGA RSFSR, f. 2306, o. 13, ed. khr. 52, ll. 9–10, 28; Liublinskii, Bor’ba, 184–185, 188–190. For a description of the similar responsibilities of obsledovateli-vospitateli in Ukraine, see Detskoe pravo, comp. Krichevskaia and Kuritskii, 524–530.

59. Vserossiiskoe obsledovanie, 37, 41–42; Detskaia defektivnost’, 62.

60. TsGA RSFSR, f. 1575, o. 6, ed. khr. 4, l. 134.

61. For examples of such instructions and resolutions, see TsGAOR, f. 5207, o. 1, ed. khr. 6, ll. 15, 62; Detskii dom, comp. Utevskii, 7.

62. TsGAOR, f. 5207, o. 1, ed. khr. 41, l. 7; Vserossiiskoe obsledovanie, 33, 35.

63. TsGAOR, f. 5207, o. 1, ed. khr. 41, l. 10; ibid., ed. khr. 62, l. 23; ibid., ed. khr. 63, l. 21; Vserossiiskoe obsledovanie, 38. For a decree and a Party resolution condemning the appropriation (except in military emergencies) of buildings housing children’s institutions, see SU, 1921, no. 64, art. 470; Detskii dom, comp. Utevskii, 7.

64. TsGAOR, f. 5207, o. 1, ed. khr. 43, ll. 8–9; ibid., ed. khr. 60, l. 131; ibid., ed. khr. 61, l. 70; Kommunistka, 1921, nos. 14–15: 7; Kalinina, Desiat’ let, 80; Krasnaia nov’, 1923, no. 5: 206–207; Golod i deti, 38, 40; Vestnik prosveshcheniia T.S.S.R. (Kazan’), 1922, nos. 1–2: 26; Prosveshchenie (Viatka), 1922, no. 1: 19; British Foreign Office, 1922, reel 1, vol. 8148, p. 128. This, of course, does not belittle the energetic work of many officials and volunteers who succeeded in saving thousands of children. For an illustration of their accomplishments, see Krasnaia nov’, 1923, no. 5: 213. Unfortunately, thousands of other children in the region died all around them.

65. Otchet gorskogo ekonomicheskogo soveshchaniia (1923), 122; Golod i deti, 15; Prosveshchenie (Krasnodar), 1921–1922, no. 2: 127 (regarding Simbirsk province); Pravda, 1921, no. 204 (September 14), p. 1.

66. TsGA RSFSR, f. 1575, o. 6, ed. khr. 4, l. 83; Otchet o sostoianii narodnogo obrazovaniia v eniseiskoi gubernii, 14–15; Diushen, Piat’ let, 27; Prosveshchenie (Viatka), 1922, no. 1: 20; Obzor narodnogo khoziaistva tambovskoi gubernii oktiabr’ 1921 g.–oktiabr’ 1922 g. (Tambov, 1922), 32; Biulleten’ tsentral’noi komissii pomoshchi golodaiushchim VTsIK, 1921, no. 2: 40–41.

67. Leningradskaia oblast’ (Leningrad), 1928, no. 4: 112; Golod i deti, 22.

68. TsGAOR, f. 5207, o. 1, ed. khr. 43, l. 67; ibid., ed. khr. 61, l. 114; Na pomoshch’ rebenku (Petrograd-Moscow, 1923), 47; Obzor narodnogo khoziaistva tambovskoi gubernii, 32; Detskii dom, comp. Utevskii, 4; Narodnoe prosveshchenie (Kursk), 1921, no. 10: 52; Shkola i zhizn’ (Nizhnii Novgorod), 1927, no. 10: 57–58; Vasilevskii, Besprizornost’, 81; Kommunistka, 1922, no. 1: 8; Otchet vladimirskogo gubispolkoma i ego otdelov 14-mu gubernskomu sъezdu sovetov (10 dekabria 1922 goda) (Vladimir, 1922), 51, 55; Otchet sovetu truda i oborony za period 1/X 1921 g.–1/IV 1922 g. (Kursk, 1922), 40. Educational institutions of all types, not just those for besprizornye, experienced this decline in numbers; see Stolee, “Generation,” 67. A report from Vladikavkaz also noted that NEP had encouraged the former owners of buildings and other property, confiscated earlier and put at the disposal of detdoma, to petition for the return of these items; TsGAOR, f. 5207, o. 1, ed. khr. 43, l. 67.

69. Kalinina, Desiat’ let, 81–82.

70. TsGA RSFSR, f. 1575, o. 6, ed. khr. 4, l. 26; Narodnoe prosveshchenie, 1922, no. 102: 8; Biulleten’ saratovskogo gubotnaroba (Saratov), 1921, nos. 2–3: 1. In separate operations, several hundred thousand adults and whole families were also evacuated from famine provinces. See Itogi bor’by s golodom, 468; Bich naroda, 94; Na fronte goloda, kniga 1 (Samara, 1922), 37; Vlast’ sovetov, 1922, nos. 1–2: 45–48; nos. 4–6: 34–37. The recent past had witnessed two other mass evacuations (though neither was focused on orphans and other homeless children), one to remove people from the front during World War I and the other during War Communism to transport children out of starving cities, including Moscow. (Some children were also evacuated from areas of military activity at this time.) For autobiographical sketches of children evacuated during World War I, see Besprizornye, comp. Kaidanova, 31; Kaidanova, Besprizornye deti, 60–61, 70. Regarding evacuations during War Communism, see Kalinina, Desiat’ let, 30; Pervyi vserossiiskii sъezd, 47; Letnie kolonii. Sbornik, sostavlennyi otdelom reformy i otdelom edinoi shkoly narodnogo komissariata po prosveshcheniiu (Moscow, 1919), 8; Krasnaia gazeta (Petrograd), 1919, no. 72 (April 1), p. 2; Narodnoe prosveshchenie, 1923, no. 6: 129.

71. TsGAOR, f. 5207, o. 1, ed. khr. 6, l. 54; ibid., ed. khr. 63, l. 42; TsGA RSFSR, f. 1575, o. 6, ed. khr. 4, ll. 22–23, 29; Biulleten’ saratovskogo gubotnaroba (Saratov), 1921, nos. 2–3: 1; Biulleten’ tsentral’noi komissii pomoshchi golodaiushchim VTsIK, 1921, no. 2: 46.

72. TsGAOR, f. 5207, o. 1, ed. khr. 28, l. 7; ibid., ed. khr. 60, l. 153; ibid., ed. khr. 61, l. 70; ibid., ed. khr. 65, l. 95; ibid., ed. khr. 67, l. 52; Narodnoe prosveshchenie (Saratov), 1922, no. 3: 26; Biulleten’ tsentral’noi komissii pomoshchi golodaiushchim VTsIK, 1921, no. 2: 38–39.

73. TsGAOR, f. 5207, o. 1, ed. khr. 44, ll. 1–2; Golod i deti, 11.

74. Itogi bor’by s golodom, 468; Narodnoe prosveshchenie, 1923, no. 8: 25; Spasennye revoliutsiei, 32; Min’kovskii, “Osnovnye etapy,” 40; Biulleten’ tsentral’noi komissii pomoshchi golodaiushchim VTsIK, 1921, no. 2: 44; TsGAOR, f. 5207, o. 1, ed. khr. 13, l. 21; TsGA RSFSR, f. 1575, o. 6, ed. khr. 4, l. 21; Chto govoriat tsifry, 14. A. N. Kogan (citing Sputnik kommunista, no. 16 [1922]: 94) presents a figure of 121,018 children evacuated by June 1, 1922; see Kogan, “Sistema meropriiatii,” 235. For reports from several regions suggesting that a majority of the evacuees were orphans or otherwise homeless, see Otchet o deiatel’nosti saratovskogo gubernskogo ispolnitel’nogo komiteta, 57; Krasnaia nov’, 1932, no. 1: 36; Bich naroda, 25; Smolenskaia nov’ (Smolensk), 1922, no. 6: 12.

75. TsGAOR, f. 5207, o. 1, ed. khr. 13, ll. 10, 17; ibid., ed. khr. 23, l. 1; ibid., ed. khr. 33, l. 2; Golod i deti, 10; Chto govoriat tsifry, 15; Biulleten’ tsentral’noi komissii pomoshchi golodaiushchim VTsIK, 1921, no. 2: 38; Konius, Puti razvitiia, 142–143; Bich naroda, 25; TsGA RSFSR, f. 1575, o. 6, ed. khr. 4, l. 21; TsGA RSFSR, f. 2306, o. 70, ed. khr. 2, l. 7; Grinberg, Rasskazy, 18; Smolenskaia nov’ (Smolensk), 1922, no. 1: 5; Gudok, 1921, no. 398 (September 11), p. 1; Novyi put’ (Riga), 1921, no. 145 (July 29), p. 3; Derevenskaia pravda (Petrograd), 1921, no. 120 (September 21), p. 3.

76. TsGAOR, f. 5207, o. 1, ed. khr. 4, ll. 1, 7; ibid., ed. khr. 65, l. 117; Novyi put’ (Riga), 1921, no. 213 (October 16), p. 3; Narodnoe prosveshchenie, 1922, no. 102: 14–15; 1923, no. 8: 25–26; British Foreign Office, 1922, reel 1, vol. 8148, pp. 82–83 (reference to a group of 439 Russian children evacuated to Czechoslovakian foster families). Turkey apparently also offered to accept a group of orphans from the Volga region, though it is unclear whether the children were ever sent; see Pravda Zakavkaz’ia (Tiflis), 1922, no. 8 (May 11), p. 2. The British government balked at permitting entry to Volga children, citing the “risks to public health that would be involved even if the strictest precautions were observed”; British Foreign Office, 1922, reel 1, vol. 8149, p. 75 (for the quotation and reference to “a party of Russian boys” already admitted to France); 1922, reel 17, vol. 8205, pp. 115–127. An American Red Cross document noted that earlier, before the famine, Polish Red Cross officials expressed a desire to remove Polish orphans from Siberia and place them in Polish-American families; American Red Cross, box 916, file 987.08, “Weekly Report,” May 18, 1920. This report does not indicate whether such a transfer took place.

77. Gor’kaia pravda, 24; Biulleten’ tsentral’noi komissii pomoshchi golodaiushchim VTsIK, 1921, no. 2: 46; Derevenskaia pravda (Petrograd), 1922, no. 23: 2; Itogi bor’by s golodom, 468.

78. TsGAOR, f. 5207, o. 1, ed. khr. 23, l. 3; ibid., ed. khr. 53, ll. 22–23; ibid., ed. khr. 63, l. 105; Biulleten’ tsentral’noi komissii pomoshchi golodaiushchim VTsIK, 1921, no. 2: 45; Narodnoe prosveshchenie (Saratov), 1922, no. 3: 25; Bich naroda, 25.

79. TsGAOR, f. 5207, o. 1, ed. khr. 13, l. 15; TsGA RSFSR, f. 1575, o. 6, ed. khr. 4, l. 29; Narodnoe prosveshchenie (Saratov), 1922, no. 3: 27. Instructions received in Kazan’ indicated that youths of preschool age should not be evacuated, and these orders doubtless went to other famine regions as well; see Vestnik prosveshcheniia T.S.S.R. (Kazan’), 1922, nos. 1–2: 25. Anna Grinberg’s book Rasskazy besprizornykh o sebe contains many autobiographical sketches by children who underwent evacuation. For similar accounts, see Kaidanova, Besprizornye deti, 56–57.