Withdrawing Without Provocation

In general, workers in the oil camps, among the wells and pump stations, were less skilled and less privileged than refinery laborers. More primitive conditions governed their lives in the countryside. Nevertheless, the oil-field workers still enjoyed some of the same opportunities (though restricted by revolutionary depredations) in addition to similar limitations of advancement. Small towns had sprung up throughout the oil zone during the boom. Along the railway lines through Chijol and El Ebano and between the great oil camps of the Faja de Oro, migrants established little population centers quite miserable in their amenities. Geologist Ezequiel Ordóñez, like others of his class, had a somewhat puritanical attitude about workers. He described these small populations as "seedbeds of disorder, abuse, and vice." Ordóñez thought that the prohibition of alcoholic beverages at the numerous cantinas would do wonders to make life respectable. Petty despots there controlled even the necessities of life. Ordóñez described how enterprising persons, without authorization, would tap into the water lines of the companies and sell the water for exorbitant prices to rural inhabitants.[66]

For those workers living inside the compounds of the oil camps, modern technology provided amenities, even if it could not protect them from the shocks of revolution. El Aguila personnel lived in wooden bunkhouses with bathhouses nearby. "These buildings are constructed of rough pine lumber, without any inside boarding, and framed upon hard wooden posts for foundations," as one company official described them:

All exposed woodwork [receives] two coats of good oil paint. Corrugated iron roofs are used with canvassed ceilings. All window and door openings are properly screened throughout with bronzed gauge screening for protection against mosquitos; for the living quarters, verandahs are built on the most suitable sides of the house.[67]

The camps also provided company stores, which often sold supplies and basic foodstuffs like corn and beans at discount prices. Single men ate at the company restaurant. By the end of the oil boom, the biggest camps had modest schoolhouses for the children of Mexican workers and sanitation and water works. Huasteca's property at El

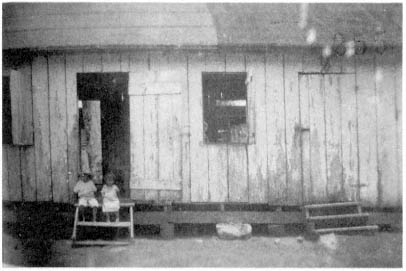

Fig. 15.

Mexican workers' housing, 1920. in the oil field of the Cortez Oil Company,

workers and their families lived in one- and two-room units in the same long

one-story building in which other families resided. Doors and windows on

either side admitted the breezes as well as the insects. from the Ramo

del Trabajo, Archivo General de la Nación, Mexico City.

Ebano was a veritable community. At any one time, up to five thousand workmen might have had ten thousand additional family members living with them in the oil camp. At Christmas time, the company entertained its employees with a sumptuous barbecue, in which the Americans served the Mexicans — surely a symbolic gesture only. In 1913, there were games, horse races, and an inspirational speech by Judge Jacobo Váldez.[68]

The small companies and the less productive oil fields, however, could not sustain the amenities of the larger camps like El Aguila's at Potrero del Llano, or Huasteca's at Cerro Azul. In the transitory camps, housing was very rudimentary, and sanitary conditions were often lacking. Still, government labor inspectors often found "very good conditions of security and hygiene" in the smaller camps of the Atlantic and the Cortez companies. Foreigners and Mexicans ate the same food, albeit at different tables. Other camps, at Saladero and Puerto Lobos, separated the housing and mess halls for foreign and Mexican

workers, tending to "deepen more the differences," as a government representative reported. At the Atlantic camp, the inspector said, "the treatment of the employees ... is always just and on some occasions even venerable."[69] The workers did complain, however, that the Chinese restaurant concessionaire refused to extend breakfast hours from 8:30 to 9 A.M.

Like the refineries, the oil camps gave in to the demands, particularly of its skilled workers, to provide separate housing and maintain the wage hierarchy. The Americans did not want to live or eat with the Mexicans; the Mexican skilled workers did not wish to live the same as the more transitory peons, and no one cared to mingle with the Chinese cooks and servants. Large camps separated the housing and operated segregated mess halls. Wage disparities also remained, especially between the foreign and the native personnel. On the drilling crews, the American drillers and tool dressers made between ten and fourteen gold pesos per day, while the Mexican firemen and helpers earned two and three pesos. The American rig builder worked for fourteen pesos per day and his three Mexican helpers got two to four pesos.[70] The Mexicans themselves earned higher wages than they could have in other lines of work. They even got 30 percent of their wages while on sick call. As the oilmen were fond of pointing out, other Mexican employers such as landowners and businessmen disliked the foreign employer "for spoiling their cheap labor."[71] There also remained a hierarchy of pay among Mexicans. The foremen (cabos ) of construction crews received up to 3.00 gold pesos per day; the peons received 1.50 pesos. Carpenters earned 4.00 pesos, blacksmiths and teamsters, 3.50 pesos; watchmen 3.00 pesos, and a camp peon 2.00 pesos.[72] There were almost as many peons in the various oil-field crews as skilled workers — but many more in construction. The wage hierarchy among Mexicans differed little from the colonial mining industry or from traditional hacienda work.

Meanwhile, the companies paid the Chinese workers the lowest wages of all. At the Potrero camp of El Aguila, twenty-five Chinese men were employed in the boarding of the foreign and Mexican employees of the construction and pipeline departments. But their monthly wages averaged less than Mexican workers. The Mexican "stable peon" made as much as the Chinese "kitchen chief" (see table 11). To a certain extent, the workers themselves determined what wages they would work for; no American would accept a Mexican's pay and no Mexican a Chinese wage. Therefore, the capitalist had to ac-

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

cept the traditional ethnic divisions of labor produced by the multiracial environment. No doubt cost-cutting employers would have preferred paying everyone the Chinese wage. But they could not.

Oil-field workers, however, endured two opposing stimuli during the period of simultaneous revolution and oil boom. On one hand, foreigners, Mexicans, and the Chinese alike all benefited from full employment. On the other, they all suffered from the insecurity caused by military and bandit activity in the countryside. The Mexicans, in particular, already encountered the customary change in time and work discipline when they entered oil-field employment. But the oil camp peons resisted giving their lives over completely to proletarianization, that is, working exclusively for industrial wages. As a labor inspector said, "The majority are from this region who work only in times in which there are no harvests. When harvests come, they leave their work, because some of them are owners of small plots which they sow for their own benefit."[73] The more skilled refinery workers did not have the same alternatives to proletarianization.

Nonetheless, the oil camps offered the Mexicans no security at all from the depredations of the Constitutionalist troops. To rob them, carrancistas shot the Mexican peons who were building a tank farm at The Texas Company field on the Obando lease. Eighteen carpenters working on a Huasteca pump station fled for their lives after the Constitutionalists took all their clothes. (The company, by the way, refused to reimburse them. Their loss was termed "a burden of Mexican

citizenship.")[74] The managers of company after company complained of the impossibility of keeping men on the job because of the "unsatisfactory and disturbed condition of affairs." Fortunately for the companies, most of the pipelines had already been built when the first outrages began during the Madero revolt. Thereafter, work on tank storage and other facilities had to be delayed from time to time.[75] Both Mexicans and Americans were abandoning the insecurity of the oil camps. "In normal times," reported the manager of the Furbero camp, "the company employes [sic ] about 600 men in the oil business and on its pipelines, railways, etc. Since 1914, however, this number has been reduced to 200, most of whom are Mexicans. All Americans have been withdrawn from the field and their places have been taken by Englishmen."[76]

Given the conditions in the countryside, the employers praised their oil-field workers, more so than refinery workers, for their loyalty. Managers often pointed out those instances where Mexican peons showed great fealty in the face of revolutionary despoliation. During the tense final weeks of the Madero revolution, Herbert Wylie said, the Mexicans patrolled the oil camps at night while American residents slept with their doors unlocked. He recalled asking them if they would be prepared to fight. "Si, señor," came the reply. "We will fight or die if necessary to protect you."[77] (They knew just what Wylie wanted to hear. I have found no evidence that Mexican field workers ever placed themselves in the line of fire to save foreign oilmen.)

The test came in 1914. When word spread that the U.S. Marines had landed at Veracruz, the Americans vacated the oil fields in panic. No sooner had the supervisors and skilled workers left than the owners realized the dangers of abandoning the oil fields: runaway wells, burst storage tanks, broken down pumps, equipment theft, destroyed railway rolling stock, and fire. The Mexican workers missed two payrolls during the month's absence of their foreign managers. Yet they stayed on the job, maintaining the oil wells and storing the excess oil in earthen reservoirs. Concluded the American consul at Veracruz:

The small amount of damage which had been done to vast oil properties which were abandoned thirty days ago is largely due to fidelity of Mexican employees and generally speaking Mexican employees and servants have been very faithful to Americans who left them in charge of property in oil fields and in Tampico without funds for sustenance and in many cases with wages due them. The small losses is [sic ] remarkable under the circumstances and great credit is due such employees and servants.[78]

Occasionally, the foreigners overstepped the bounds of their workers' loyalty. These instances pertained to the individual Mexican's penchant to resist the undesirable aspects of proletarianization and preserve traditional individualism and mobility. The Mexicans in the oil industry, especially in construction, still clung to tarea (piecework) so that they could take off whenever they pleased. When fired with special indignity, the Mexican workman might round up several friends in order to lay an ambush for the offending foreign supervisor.[79] The foreign employers never did understand the Mexicans' ambivalent attitude about the material improvements, social welfare, and educational opportunities that the oil companies provided. Just when the company gave him benefits not to be found elsewhere, the individual might walk away from the job. "In spite of these [benefits], the workers show no particular loyalty to the company," reported one informant, "and are ready to sacrifice its interests both by rendering poor service, and by withdrawing without provocation."[80] Many a manager puzzled over the Mexican worker's propensity to preserve his independence. For the most part, the oil-field worker did not subscribe to labor militancy as a remedy to his problems. After all, he was not as dependent as his urbanized and proletarianized brethren at Tampico. He merely took off for his piece of land.

The refinery workers, however, were different. They depended on factory wages and were more proletarianized. Therefore, they suffered acutely from the greatest problem confronting urban workers during the oil boom: the cost-of-living rise that afflicted the Mexican economy beginning in 1914. In part, this economic condition obtained throughout the Atlantic world during the First World War, when the arming of the European nations, at the same time that the best workers were conscripted to fight the war, drove commodity prices sky-high. Most Western economies, including those in the Latin Americas, remained at full employment. But rises in the price of foodstuffs and consumer items outstripped wages. Workers throughout the Americas, therefore, threatened additional disruption of the economic system. They demanded higher wages and mounted work stoppages in order to gain some relief from the rising cost of living. Strikes broke out in Buenos Aires, Santiago, Lima, São Paulo, and Mexico City.[81]

In Mexico, the Revolution compounded the economic stress. After the most violent phases of the Revolution had subsided, experts surveyed the agricultural destruction. The population of livestock in

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Mexico had been reduced by as much as 60 percent. Veracruz, home of the oil industry, did not escape this disruption (see table 12).

The squeeze on workers' pay also affected the oil industry, but the owners were reluctant to raise wages. They reasoned that once wages were raised, they could not be reduced later when the cost-of-living crisis subsided. Instead, they preferred to increase the nonmonetary benefits like restaurant and company store privileges. Inflation of the Mexican paper peso, nonetheless, threw their pay policies into disarray, forcing employers to combine paper currency, Mexican silver, and American dollars.[82] El Aguila's managers despaired that they could contain worker unrest when the value of the American dollar too began to slip. By the end of 1916, they were finding that the workers would no longer accept their salaries half in silver and half in dollars. The discount on American currency was nearly 15 percent. Mechanics, formerly paid five gold pesos per day, now would not work even for seven pesos. The managers worried about what action the workers might take when the dwindling supply of silver currency dried up completely.[83] What did the workers do? They fought back. Nothing in their labor traditions, neither the outward appearance of servility nor the government's occasional use of repression had taught Mexican workers to accept as final such deteriorating conditions. To the contrary, they had learned that their demands, petitions to the state, and strikes often succeeded in yielding some relief. Oil workers at Tampico were to encounter remarkable successes in this regard, partially because the Mexican Revolution had fostered propitious developments in labor organization and had conditioned the state to be receptive to labor demands.