Epilogue—

The Deaths of Two Women

Two years before Queen Elizabeth died, Katherine Brettargh died. Three years before King James died, Mary Gunter died. Brettargh and Gunter were obscure figures, but their crises of faith were notable enough to merit preservation in funeral publications, and together they may help to prove that the battle between Protestantism and Catholicism in this period bred atheistic doubts that focused most intensely on the prospect of death. The case of Brettargh shows how the deathbed terror of an individual provoked the society at large to reveal, in the form of argument between Protestants and Catholics, its annihilationist anxieties. The case of Gunter is more explicit, showing how an individual internalized that doctrinal schism as personal terror. In both cases the emotional needs of the women were repressed on behalf of the endangered Christian hegemony; the consolations failed, but the appearances had to be saved. The blankness of death had to be concealed, even if that required disguising it as the devil.

Like many of the Metaphysical lyrics I have been discussing, like conversion narratives in general, these women's stories were made to affirm, within the span of life, the promise of spiritual redemption after death—a promise that, especially for Calvinists, was disturbingly difficult to verify. Narratives of Puritan deaths as well as lives had to rehearse a pattern of desperate fall and joyous recovery, even when that required distorting the data. I hope these cases will add a meaningful emotional note to the conclusion of my long analytic argument. Ending with these

biographies rather than with any further anatomies of imaginative literature reflects a recognition that human life-stories matter to me in ways the more abstruse functions of language and criticism do not, and a belief that literary analysis has an ultimate obligation to nurture human sympathy.

Katherine Brettargh

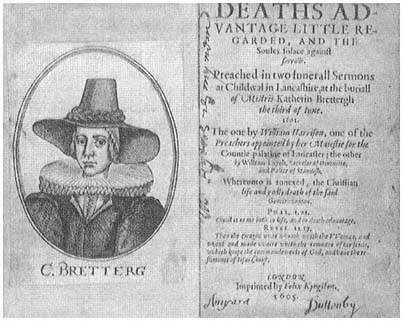

My sympathetic encounter with Katherine Brettargh began with the frontispiece of her funeral sermon: the Puritan hat and ruff look like millstones about to crush a haunted young face. My search for her legacy reached a dead end in a massive old chronicle of the region, which made the destiny of her only child a blank on the genealogical chart, and showed her entire family line ending more than two centuries ago, surrendering their name and their small ancestral manor a few miles from the city of Chester.[1] In between, her life story emerged mostly in subordination to that of her eldest brother, John Bruen, of the village of Bruen Stapleford. According to an 1848 commentator on a 1617 journal, John Bruen became a small-town hero of early Puritanism: "In the year 1587 he lost his father, and the care of twelve brothers and sisters, their education and fortunes, devolved upon him," and he "regulated his household according to the strict rules of religion. His self-denial and energy of character, were worthy of primitive times, although it must be admitted that some of his proceedings were singularly fanatical, and are calculated rather to excite a smile than to admit of imitation."[2]

What exactly are we being invited to smile at? According to a worshipful 1641 biography, in response to a pious recognition that hunting was cruel and immoral, Bruen "presently killed up the game, and disparked the Parke"—a paradoxical kindness, familiar perhaps from Spenser's Guyon in the Bower of Bliss. Since "Papists will have Images to bee lay mens bookes, yet they teach no other lessons but of lyes," and since the elaborate stained glass windows in the local chapel at Tarvin served to "obscure the brightnesse of the Gospell, [Bruen] presently tooke order, to pull downe all these painted puppets, and popish idols, in a warrantable and peaceable manner." This same impulse replicated itself in the domestic sphere: "finding over the Mantletree a paire of new cards, no body being there, I opened them, and tooke out the foure knaves, and burnt them." Other amusements fared no better: Bruen also reports that he took "the Dice, and all the Cards I found, and put them

2.

Frontispiece and title page from William Harrison,

Deaths Advantage Little Regarded (London, 1605).

Reproduced by permission of The Huntington

Library, San Marino, California. RB230048.

into a burning Oven, which was then heating to bake Pies," because he considered them "grosse offenders, and such as could not have their faults (otherwise than by fire, or fornace) purged from them."[3]

As eccentric as these actions may seem, they are logical extensions of a basic Christian consolation for death: the belief (which Calvinism magnified) that things must be utterly destroyed in order to be eternally saved. The closing joke about "grosse offenders" makes it clear that this fiery zeal applied fully to Bruen's fellow humans. Indeed, his piety is described as arising directly from sharp punishments by his earthly father; and, passing on the favor, he "did not spare to use the rod of correction as Gods healing medicine to cure the corruptions of his children." When this zeal would cause him to "deale too violently with his hands," Bruen would then "have recourse unto his heavenly Father by humble and hearty prayer."[4]

After the death of his first wife, John Bruen married a daughter of John Foxe, and may then have made minor domestic martyrs of his family: "On his return to Bruen Stapleford he continued his eccentric

though unaffected career of piety, ruling his house well, and rendering it a pattern of Christian morality." Somewhere in that pattern was "his saint-like sister, Mrs. Katherine Bretturgh or Brettargh"; but neither of these rather lengthy accounts of John's life manages to remark on what was, at the time, considered Katherine's very remarkable death.[5]

Doubtless some allowance should be made for the hagiographic tendencies of the occasion, but William Harrison's funeral sermon on Katherine Brettargh convincingly portrays her as an extraordinarily pious Puritan, in conduct as well as in sensibility:

She was by nature very humble and lowly, not disdaining any: very loving and kind, shewing courtesie to all: very meeke, and milde, in forbearing every one; so as they which daily did converse with her, could never see her angrie: and hereby she got the love of all. . . . so did she accustome her selfe to reade every day eight Chapters in the bible [and on the Sabbath] was greatly grieved, if she might not heare one or two Sermons. . . . She had a very tender conscience, and would often weepe not only for her owne sins, but also for the sins of others; especially if she espied a fault in those which were neere unto her, & whom she loved dearely.

She had evidently learned this last lesson from her brother, and duly applied it to her husband, through provocations great and small:

It is not unknowne to Lancashire , what horses and cattell of her husbands were killed upon his grounds in the night, most barbarously at two severall times by Seminarie Priests (no question) and Recusants that lurked thereabouts. And what a losse and hinderance it was unto him, being all the stocke bee had on his grounds to any purpose. This fell out not long after shee was married to him; yet . . . turning it into matter of praising God . . . Many times shee would pray that God would forgive them, which had done them this hurt, and send them repentance: and she would call upon her husband, that he would doe the like . . . without either desire of revenge, or satisfying his owne affections.

On a time, as her husband and shee were riding toward the Church, hee was angry with his man: Alas husband (quoth she) I feare your heart is not right towards God, that can be thus angry for a trifle . . . . Another time, a tenant of her husbands, being behinde with his rent, she desired him to beare yet with him a quarter of a yeare, which he did: and when the man brought his money, with teares she said to her husband: I feare you doe not well to take it of him, though it bee your right, for I doubt he is not well able to pay it, and then you oppresse the poore .[6]

This saintliness (perhaps easier for a husband to appreciate after her death) makes her deathbed crisis at once more explicable and more

poignantly unjust. It was all too easy for her to blame her own venial moral failings for her deathbed agonies—a perverse consolation fundamental to Christian theodicy. The idea that these agonies foretold her damnation would of course have been unbearable, but no more so than the idea that they meant nothing, and that her lifelong forebearances would never be rewarded. She might have cried, like Herbert's pilgrim, "Alas, my king; / Can both the way and end be tears?"

These aspects of Katherine Brettargh's story are legible in a rather polemical narrative of her embattled life and death appended (in several editions) to the two sermons preached at her funeral in Childwall church on the third of June, 1601. The first sermon, by the Puritan preacher William Harrison, took its text from Isaiah 57:1 in the Geneva Bible: "The righteous perisheth, and no man considereth it in heart." Harrison's treatment first caught my attention because it seemed to be struggling to exclude an annihilationist suspicion, insisting that the word "perisheth . . . must not so be understood, as if he were quite destroyed, brought to nothing, and had no more being: as it befalleth bruite beasts at their death, whose soules being traduced with their bodies are mortall, and perish with their bodies: the righteous hath a being even after death." Harrison avoids even mentioning the possibility that people might understand death as a mere and universal fact of nature. Instead he insists that people see in it the mysteries of divine providence: "This carelesse contemning of their death, doth shew that ye harts of the comon people were possessed with great securitie, to make so small reckoning of such a strange worke of God." But how strange is it, in the common mind, that righteous people die like everyone else? Harrison adduces a standard sacred binarism to redeem death from its terrifyingly apparent indifference: "The godly are taken out of the world, because the world was not worthie of them ," Harrison asserts, "but the wicked are taken away, because they are unworthie to live in the world."[7] To relinquish the absolute Calvinist dyad of elect and preterite would be to admit that some people die because all people die. Moralizing death replaces an ontological mystery with a familiar transaction of punishment and reward.

The resulting compulsion to find portents of the afterlife in the scene of the deathbed places Harrison in the peculiar position of first insisting through most of his sermon that "an evill death can never follow a good life," and then having to close the same sermon by lauding a woman renowned for her miserable death as well as her pious life.[8] Harrison was

not present during the worst of Brettargh's crisis, but those who had observed her raging against her pain and "want of feeling Gods mercie," accusing herself of unbelief and terrible sins, and throwing her Bible repeatedly to the floor, must have listened uneasily to the core of Harrison's funeral sermon:

The wicked . . . dye impatiently, who doe not willingly beare the Lords correction, deserved by their sinnes; but rage, fret, and murmure, as if God dealt too rigorously with them. . . . Others die desperatly, their consciences accusing them most terribly for their sins. . . . The consciences of many wicked men lye quietly, and never trouble them all their life time, but are stirred up at their death, and then rage and torment them like a mad dog which is lately awaked out of sleep. But the righteous die most comfortably. . . .

Eventually Harrison evades the implications of this doctrine for Katherine Brettargh by at once externalizing her troubles into Satan and dismissing them as mere physiological manifestations of her bodily illness:

if the righteous a little before death be dangerouslie tempted by Sathan, and shew their infirmitie by uttering some speeches which tend to doubting or desperation (though afterward they get victory, and triumph over the divell) carnall people think there is no peace of conscience, and therefore no salvation to bee had, by that religion: and so speake evill of it.

Lastlie, others beholding them which were reputed righteous, to die very stranglie, to rave, to blaspheme, to utter many idle and impious speeches, to be unrulie and behave themselves verie foolishlie, they begin to suspect their profession: but let them know, that these things may arise from the extremitie of their disease. . . . it is not they which doe it, but the disease which is upon them.[9]

A Catholic who dies in anguish is being punished by God for sin and confessing hypocrisy; a Puritan who dies in anguish is being assaulted by the devil for virtue, and displaying the distortions naturally accompanying a high fever.

Yet there is more at risk here than factional propaganda; in defending Puritan Christianity, Harrison risks compromising Christianity as a whole. The parallel between demonic possession and biological disease in these passages threatens to expose the entire Christian scheme as an evasive allegorization of the hard facts of nature. Nor was this the only time this family had encountered that threat. Confronted with a case of supposed demonic possession that bears strong resemblances to his sister's deathbed crisis ("If one came neare him with a Bible," the

possessed boy tried "to rend it in peeces"), John Bruen fought to preserve the supernatural moral drama: though "some ascribed all to naturall causes, few did endevour to see and acknowledge (as this Gentleman did) that though Satan might have a finger, yet the Lord had a chiefe hand in this Judgment."[10]

Harrison's sermon strives to contain a threat that goes far beyond Katherine Brettargh's personal reputation: "I have heard that some speake very uncharitably of her, by reason of her temptation, and thereupon mutter much against religion it selfe: but such should remember that which I have spoken before, that the Devill most assaulteth them which be most godly, thinking to hinder all religion, if he may prevaile with such."[11] Christianity thus anticipates the selfverifying device of the modern belief-system called psychoanalysis, in which every lapse in the supporting evidence can be attributed to the repression of that evidence; in the case of Harrison's sermon, every visitation of atheistic doubt confirms the workings of Satan, and hence the existence of God. If Katherine Brettargh had been tormented simply by a fear that Christian damnation rather than Christian salvation was imminent, or if her torment had been merely an occasion for Catholics to condemn Protestantism, why should it have provoked mutterings "against religion it selfe"; how could it "hinder all religion" as Harrison charges?

Harrison's larger anxieties suggest that Katherine Brettargh's deathbed crisis had annihilationist overtones. Pain and fever produced delirium, doubt, and resentment. Lacking an alternative discourse of Existential heroism, the pious observers in the sickroom—including Brettargh herself—were obliged to perceive these symptoms as diabolical temptation in order to avoid perceiving them as mere biology. Restored to the orthodox categories, her sufferings became commodities accessible to the competing claims of Catholicism and Protestantism. The Devil is placed in the sick-room to block a window into nonreligious death, and the unnamed complainants against religion per se may have been—anticipating radicals such as Winstanley[12] —condemning the way pressures toward religious orthodoxy demanded that the dying woman generate spiritual misery to match her physical condition, a sort of theological inversion of pathetic fallacy. Without that subjective correlative, death is ruined as a work of divine art and divine justice.

The other sermon delivered at Katherine Brettargh's funeral, by William Leigh (who elsewhere declares that there can be "no blessed life without a blessed death")[13] manifests similar symptoms of resistance to

some lurking annihilationist initiative. Leigh chooses a text concerning the sleep of the righteous, which he describes as

an Antidote to prevent a poyson much infecting all flesh: who without all comfort of future blessednes, do, to the hazard of their soules, stand doubtfull of the resurrection, as also of the rest of their soules, after they be departed. The one sort are the Atheists , the other are the Papists of these dayes & times: but the text is powerfull to put backe both Jordans , that the Israel of God may enter Canaan without crosse or feare. For if the Lords elect shal rest in their beds, they shal rise from their beds. Rest implyeth a resurrection, when the time of refreshing shall come. It is an improper speech to say, hee resteth, who never riseth. It may bee some go to bed who never rise, strooken with a deadly sleepe or lethargie, but none to the grave, but out he must, at the generall sommons. . . .

The obvious speciousness of such an argument is less important in itself than as a symptom of the compulsion to make an argument. After a series of anxious references to lost sight and heating, Leigh concedes that when Brettargh fell ill, "The Lord hid his face from her, & she was troubled."[14] In the context of Brettargh's particular anxieties, this Scriptural formula begins to sound like a euphemism for the terrifying idea of a deus absconditus .

Two poems appended to these sermons also attempt to control the interpretation of Katherine Brcttargh's far-from-tame death.[15] The first, under the guise of allowing the deceased to testify posthumously in her own behalf, personifies her disbelief as a safely conventional Christian adversary: "True it is I strove: But 'twas against mine enemie," declares the opening line. The other poem, a kind of antiphonic response, begins, "It's not unlike (Christ's deare) such conflict you endur'de." The parenthetical compliment—indeed, the entire invention of a posthumous dialogue—begs the fundamental question.

The terms of our responses having been thus prepared and circumscribed, the narrative of her life and death can begin. Still, when that narrative arrives at her final illness, the syntax becomes notably rich in defensive modifications and subordinate clauses, and notably determined to achieve a happy piety before yielding to its own closure:

Her sicknes tooke her in the manner of a hot burning Ague , which made her according to the nature of such diseases, now and then to talke somewhat idly, and through the tempters subtiltie, which abused the infirmitie of her bodie to that end, as he oftentimes useth to do in many, from idle words, to descend into a heavy conflict, with the infirmitie of her owne spirit; from the which, yet the Lord presently and wonderfully delivered her. . . .

But this delivery comes only after considerable labor pains: "she began to feele some little infirmitie and weaknes of faith. . . . shee thought shee had no faith, but was full of hypocrisie. . . . Sometime she would cast her Bible from her."[16] Particularly if one allows for the euphemizing tendency of the pious narrator, this sounds more like an abandonment of Christian religion than like a fear of Christian damnation.

A woman of such selfless piety might begin to mistrust the justice—and hence the existence—of the Christian God as she lay in mortal agony at age twenty-two. This is hardly an anachronistic speculation, because the narrator feels compelled to defend against it, as perhaps Brettargh did herself:

Many times shee accused her selfe of impatience, bewayling the want of feeling Gods spirit, and making doubt of her election, and such like infirmities. Shee wished, that she had never beene borne. . . . But every one saw that these things proceeded of weakenes, emptines of her head, and want of sleepe, which her disease would not affoord her.

These fits though they were for the time grievous to her selfe, and discomfortable to her friends: yet were they neither long nor continuall, but in the very middest of them, would she oftentimes give testimonie of her faith. . . . Once in the middest of her temptation, being demaunded by Master William Fox: whether she did beleeve the promises of God, nor no? and whether she could pray ? she answered: O that I could, I would willingly, but he will not let me. Lord I beleeve, helpe my unbeliefe .[17]

However paradoxical, this last plea is a common enough quotation (from Mark 2:24) among struggling Christians. But it becomes increasingly clear that Brettargh resorts to quoting such Christian formulas because she cannot believe deeply or spontaneously in the promise of personal afterlife she so badly needs on this premature deathbed:

And when shee was moved to make confession of her fath, shee would doe it oftentimes, saying the Apostles Creede , and concluding the same with words of application to her selfe: I beleeve the remission of (my ) sinnes, the resurrection of (my ) bodie, and eternall life (to mee ) Amen . And having done, she would pray God to confirme her in that faith. . . . But the difficulty shee had sometimes to apply these generals unto her owne soul in particular, made the case more full of anguish to her selfe, and fearefull and lamentable to the standers by.[18]

The poignance of this "difficulty" needs little pointing—except perhaps to Foucauldian critics and historians who would claim that only the alienated individualism of a twentieth-century episteme could produce this sort of anomie . When this woman found that she "could hardly

appropriate each thing to her selfe," she exposes the damage that Reformation individualism (with its inward God and His inscrutable election) had already done to conventional Christian consolations for death.

At last, this narrator insists, came a happy ending: "being laide downe againe in her bed, she confidently spake these words: I am sure that my redeemer liveth, and that I shall see him at the last day, whom I shall see, and mine eyes shall behold: and though after my skin, wormes destroy this bodie, yet shall I see God in my flesh with these eyes, and none other ." Thus finally the wild death of Katherine Brettargh was tamed by the promise of afterlife, tapering off from the sufferings of Job to a pious silence, but not without a Desdemona-like coda of loving forgiveness toward the Lord who decreed her terrible death:

her tongue failed her, and so she lay silent for a while, every one judging her then to be neere death, her strength and speech failing her: yet after a while lifting up her eyes with a sweete countenance and still voyce, said . . . he is my God, and will guide me unto death: guide me O Lord my God, and suffer me not to faint, but keepe my soule in safetie . And with that shee presently fell a sleepe in the Lord, passing away in peace, without any motion of body at all; and so yeelded up the Ghost, a sweete Sabboaths sacrifice about foure of the clocke in the afternoone, of Whitsunday , being the last of May 1601.[19]

The narrator thus seizes on the instant of tame death, and plants it firmly back in a Christian frame of time.

The justification offered for appending this "Brief Discourse," with its extensive and harrowing account of Katherine Brettargh's deathbed suffering in body and soul, seems almost as perverse as the thematic argument of Harrison's sermon. At the very least, this justification resounds with denial:

But sure her death was such, her behaviour in her sicknes so religious, her heart so possessed with comfort, her mouth so filled with praises of God, her spirit so strengthened against the feare of death, her conquest so happy over her infirmities, that such as loved her most have greatest cause to rejoyce in her death, and by seeing the wonderfull worke of God in her, to learne to renounce their owne affections. . . . I thought so great mercie of God shewed to one among us, ought not to be forgotten, but should remaine to us & our children an example, to teach how good God is to them that love him, and to assure us that he will never forsake us; but, in like manner as he did her, helpe and comfort us, when we shall by death be called unto him. I considered the ungodly and uncharitable tongues of the Papists abiding in our countrey, who, since her death, have not ceased to give it out that she died despairing, and by

her comfortles end, shewed that she professed a comfortles Religion. Wherein they bewray their malice & madnes. . . .[20]

Though this narrative does stress that Katherine Brettargh recovered her peace of mind in the final day of her illness, it is hard to believe her story to be such an extraordinary demonstration of God's gentleness and unfailing comfort that it demanded publication. More probably, it was sufficiently threatening that it demanded revisionistic commentary. If pious contemporary commentators could claim Katherine Brettargh as a fine example of comfortable Christian dying, then it is easy to see why modern commentators, taking the earlier ones at their word, have mistakenly supposed that all Renaissance Christians died confident of an afterlife.

Harrison claims that his purpose in publishing Deaths Advantage is "to cleere her from the slanderous reports of her popish neighbours, who will not suffer her to rest in her grave, but seeke to disgrace her after her death."[21] In fact, Katherine Brettargh's death has never been allowed to rest, in pain or in peace, as a simple fact of nature. Instead it became, in her conscious mind, a gigantic struggle between God and Satan for her soul. It became, in a skirmish of Jacobean pamphlets, a furious debate between Puritans and Romanists over which religion could promise the more merciful death. In an early example of spincontrol in the popular press, the narrator of Brettargh's life story demands of the Catholic jeerers, "what can any man see that might give just occasion to report our religion comfortles, or [that] the Gentlewoman dyed despairing," and points out the prominent Catholics "which have dyed most fearefully indeede."[22] Nor can she yet rest in peace, to the extent that I am imposing yet another abstract binarism by interpreting the same feverous delirium as a subliminal struggle between Christian orthodoxy and repressed annihilationism.

From the age of eight, Katherine Brettargh was raised by a brother who (even according to his hagiographer) "sometimes made rather too small an allowance for the material part of man, and treated him, unwisely, as altogether a spiritual being."[23] In the grip of a bitterness she could not fully understand (indeed, was forbidden to understand), in the agony of a violent fatal illness, Brettargh was left no choice but to accuse herself of spiritual failure and to anticipate eternal torment in hell. It is not a very good brief for religion, but it does exemplify the pathos and pathology of the human individual trying to comprehend and endure mortality.[24]

Mary Gunter

Mary Gunter's story survives in a "Profitable Memoriall" of "the life and death of this sweet Saint, as it was observed and now faithfully witnessed by her mourn full husband, who wisheth both his life and latter end like unto hers"—a sentiment more sweet than credible.[25] This memorial appeared in 1622, and was reprinted in 1633, both times appended to the Puritan sermon preached at her funeral. It is a form of conversion narrative, but the conversion is socially imposed:

This gracious Woman was for birth a Gentlewoman, but descended of Popish Parents, who dying in her infancy, shee was committed unto the tuition of an old Lady, honourable for her place, but a strong Papist, who nousled and misled this Orphan in Popery, till shee came about foureteene yeeres of age; at which time this Lady died. Upon which occasion, God (having a mercifull purpose towards her conversion) by his good Providence, brought her to the service of that Religious and truly honourable Lady, the Countesse of Leicester . . . . To this Honourable Countesse shee came a most zealous Papist, and resolute, as soone as possibly shee could apprehend a fit opportunity, to convey her selfe beyond the Seas, and become a Nunne. . . . But shee could not so closely carry her secret devotions and intentions, but that by the care full eye of her Honourable Lady, they were soone discovered, and not sooner discovered then wisely prevented; for presently her Lady tooke from her all her Popish bookes, Beades and Images, and all such trumpery, and set a narrow watch over her, that shee might bee kept from her Popish Prayers, and not absent her selfe from the daily Prayers of the Family, which were religiously observed: further, requiring her to reade those Prayers that her honour daily used to have in her private chamber with her women.

Her Ladiship also carefully prevented her from her Popish company and counsel by word or writing, for neither might shee write nor receive any letter without the view and consent of her Honour (pp. 159–62)

Despite the narrator's approbation, or perhaps because of it, modern readers may be reminded of the cruel benevolence by which Shakespeare's Shylock is converted, and perhaps also of the tactics employed by modern "deprogrammers" of religious cultists.

The young woman put up some strategic resistance: to cover her stubborn recusancy, "shee in short time obtayned great ability to communicate to others the substance of those Sermons" she had been forced to attend (p. 163). But mimicry soon became identity, and the concealed Self became the enemy Other. One Puritan preacher proved so compelling that "in short time, it pleased God that shee was won to

beleeve the Truth, and renounce her former superstition and ignorance. And as it is the property of a true Convert, being converted her selfe, she endevoured the conversion of others" (p. 164). This might be a valuable instance for those claiming a radical malleability of selfhood in Renaissance England, except that this conversion proved agonizingly difficult: "Now presently Satan . . . begins to rage, and reach at her with strong and violent temptations," including "the dreadfull and foule suggestion of selfe murder" (pp. 165–66). In other words, she was nearly compelled to destroy her identity in order to save it—or in order to save the Kohutian self-object in which she had formerly invested her immortality.

Mary Gunter could maintain her selfhood, her sanity, even her life, only by making her Protestantism a fetishized shadow of her former Catholicism. Forbidden the ritual comforts of the Roman religion, she made a ritual out of the Bible study central to Protestantism: "shee tyed her selfe to a strict course of godlinesse, and a constant practice of Christian Duties, which she religiously observed even till her dying day. . . . shee would every yeare read over the whole Bible in an ordinary course, which course shee constantly observed for the space of fifteene yeares together, beginning her taske upon her birthday. . . ." (p. 171). The timing is psychologically revealing: she must be born-again in order to recover the stability of her original identity, which religious schism had subverted. By systematically internalizing the text the schismatics had in common, she reconstructs herself: "by her great industry in the Scriptures, shee had gotten by heart many select Chapters, and speciall Psalmes , and of every Booke of the Scripture one choyce verse: all which shee weekly repeated in an order which shee propounded to her selfe" (p. 173). But the entwining of Protestant autobiography with the reading of Scripture could easily have reinforced a suspicion that the Calvinist salvational scheme had no room for unique interiorities. Mary Gunter built prayer-system on prayer-system, fasted (a familiar tactic for reclaiming the autonomy of the self), and kept a moralistic vigil over herself, as if she might otherwise not only sin, but disappear: "for the space of five yeares before her death, she kept a Catalogue of her daily slips, and set down even the naughty thoughts which shee observed in her selfe. . . ." (pp. 174–77). The problem she confronts here is the same Donne confronts in "Goodfriday, 1613. Riding Westward" and the Holy Sonnets, and Herbert confronts in "Good Friday" and "Judgement": the zealous Protestant must construct a narrative of the self, yet that narrative is inevitably so deeply entwined with sin that God will, at best, erase it.

In her early Papist days, Mary Gunter had been led venially astray: "Whilest shee was a childe bred up in the chamber of that old Lady, shee was entised by lewd servants who fed her with figges, and other such toyes, fit to please children withall, to steale money out of the Ladies Cabinet." Now, as a Protestant, she paid that unsuspected debt back to the Catholic woman's heir, with generous interest, from her marriage portion (pp. 178–80). But the debt of her apostasy was not so easily appeased. Her Catholicism reasserted itself as something worse: now Satan

would confound and oppresse her with multitudes of blasphemous thoughts, and doubts. Now must shee beleeve there is no God: That the Scriptures are not his Word, but a Pollicie. . . . for, how could shee be sure that this was the truth which she now professed, seeing there are as many, or more learned men of the one opinion as of the other, and all of them maintaine their opinions by the Scriptures. Thus was shee vexed and exercised with Armies of roving and unsetled conceits for five or six yeares together. (pp. 168–69)

Unable to distract herself entirely with her systematic exertions of piety, she thus settled into the kind of rational doubts supposedly impossible in this period. In doing so, she confirmed Bacon's axiom that schism in religion breeds atheism. The image of Satan was again superimposed to keep that threat from appearing in its own guise. Identifying atheism as a Satanic temptation provides a fail-safe device for Christianity; unbelief is imprisoned in a labyrinth. But that labyrinth is only rhetorical: neither the need of pious public commentators to subjugate these women's doubts to the official system, nor even the eventual willingness of the women to accept that consoling formula, undoes the fact that they were able to conceive such doubts. Christianity was no longer—if it ever had been—a perfectly self-perpetuating response to death; instead, the hysterical conjuration of Satan suggests a kind of reaction-formation in defense of the culture's theological consensus.

Mary Gunter's spirit recovered from this crisis, but her flesh "was of weake and sickly constitution many yeares before her death," and her final illness allowed a recurrence of these agonizing religious doubts:

But thirty dayes before her departure, she finding her paines increasing, and growing very sharpe and tedious, she spent an houres talke with me concerning her desire for the things of this life; and having said what she purposed, shee thus concluded her speech: Now, sweet Heart, no more words betweene you and me of any worldly thing. . . . (pp. 183–84)

All she asked was her husband's help in praying for her soul, which proved needful, because "onely three dayes before her death, she began to be dejected in the sense of her owne dulnesse, and thereby began to call in question Gods love towards her, and the truth of Gods grace in her" (pp. 185–86). Again, Calvinist preterition seems difficult to distinguish from annihilationism.

Her husband is quick to assure us that this spiritual crisis only proves how merciful God is to Puritans, "for that he had now so chained Satan at this time of her great weaknesse, that having beene formerly molested, and daily vexed with his assaults, for the space of above six yeares together, now he would not suffer him to rest on her with his malice above six houres" (pp. 186–87). Exacerbated by the slippage in the male pronouns, the manifold sexual overtones of this claim about the Satanic possession of his wife suggest that he was almost willing to be cast as the devil who tempts her, if it would rescue her from an irreligious universe. In any case, the parallel to the earlier crisis clearly suggests that atheistic annihilationism was as much a part of Mary Gunter's deathbed crisis as it was of her midlife crisis. Doubtless her deathbed anxieties expressed themselves primarily as a fear of preterition, but preterition took many forms in Mary Gunter's experience. She would have been deeply sensitized to the threat of losing her interior and relational selves. Even at the end, even filtered through orthodox Christian interpreters, her words suggest less concern with Christian damnation than with the obliteration of the identity she has built, as if she were surrendering thisworldly domesticity ("the things of this life," the structures of house and family) with no otherworldly destination.

The Christian God had provided for Mary Gunter's interiority so unreliably in life that she could easily have doubted its preservation after death. Exclusion from God had already proven a lonely experience of privation for her; it had erased the core of her former Catholic identity, and the superimposed Protestant beliefs suggested that God's presence could be known only in the interiority that was now again at risk through death. As D. W. Winnicott has speculated, the fear of death is closely related to a fear of breakdown, and those who have experienced some unacknowledged psychic death at a formative stage are likely to recognize physical death as a sort of objective correlative to the earlier psychic loss. In Heinz Kohut's terminology, a "fulfilled parting" from this life is possible only for those whose personality has "no significant admixture of disintegration anxiety."[26] Given the severe mutability of Mary

Gunter's objects of immortality and idealization, it is hardly surprising that the fear of annihilated selfhood weighed so heavily on her deathbed. Nor is it surprising, given the importance (in Kohut's view) of a reliably empathetic observer to ease these fears,[27] that her husband's vigil by the deathbed was so crucial to her endurance.

It is a commonplace of seventeenth-century religious tracts that deathbeds cure atheism, but the case of Mary Gunter, like that of Katherine Brettargh, suggests that these final agonies may have evoked rather than erased atheistical doubts and annihilationist fears. Theological schism seems to have accentuated this tendency, and it certainly accentuated the compulsion to exempt one's own faction from the taint of mortal terror. As with Katherine Brettargh, a happy ending is hastily cobbled onto Mary Gunter's terminal illness (and the only modern commentary I have found strangely whitewashes Gunter's story);[28] but it scarcely conceals the evidence that the Reformation had dangerously unsettled the standard mythology of Christian afterlife. "Neither could so gracious a life be shut up but by an answerable, that is, an happy death," the husband insists (p. 182); and Mary Gunter herself is determined to uphold that mythology, asking God for a clear mind with which to enjoy her death, "for she said, If I through paine or want of sleepe (which she much wanted) should have any foolish or idle talke, I know what the speech of the world useth to be; This is the end of all your precise folke, they die mad, or not themselves, &c." (p. 189). But are atheism and annihilationism always madness, or only maddening? And who was Mary Gunter, when she was herself?

In early seventeenth-century England, the fear of lost selfhood began to eclipse the threat of hellfire; at least for Protestants, the fear of being unloved by any deity often replaced the fear of divine anger. Like John Donne, Mary Gunter was violently dislodged in adolescence from the identity she had built around her intense Catholic indoctrination; like Donne, she fell into a period of skepticism that left her forever vulnerable to the fear of both death and personal instability. But the annihilationist anxieties haunting these apostates are also legible in figures of stable familial Protestantism such as George Herbert and Katherine Brettargh. From her parents' "dying in her infancy," from the death of the Catholic woman who raised her "to about fourteene yeeres of age," and from the tactics of isolation then used to compel her conversion, Mary Gunter would have learned the annihilationist lesson: that abandonment can be even more terrifying than punishment. But even in the assured piety of Herbert's The Temple , God's abandonment is a more real and active

threat than His punishment. When Satan torments Katherine Brettargh on her deathbed, he does so merely by forbidding her to apply the promise of salvation to herself. In a world of individuals, Satan is no longer the Seven Deadly Sins, in all their vivid allegorical guises. He is instead the figure who threatens to pull off his traditional mask; that is, to pull the mask off death, and show us its unspcakably blank face.