Part Three

5. “A Special Danger”

Gender, Property, and Blood in Nairobi, 1919–1939

This chapter is about local meanings, local usages, and local concerns. The vampire stories told in the legal African locations of Nairobi were not very different from those told elsewhere in East Africa, but they had a markedly different time frame, and, I argue, markedly different meanings. The vampire stories and the gossip about who worked for wazimamoto did more than identify unpopular accumulators or explain how bad people became rich. This chapter argues that local versions of rumor and gossip provided some of the images, metaphors, and vocabularies that created new cosmologies, new moral constructs in which new rights and obligations were invented, made concrete, and passed on. Women maintained their fragile hold on durable property rights by all the strategies colonial societies made available; they described these rights as perhaps more distinct and solid than they actually were: as this chapter shows, some of the most vocal advocates of women’s property rights were women who had never owned homes themselves. But at the same time, propertied and unpropertied women told stories about skilled wazimamoto who crept silently about women’s rooms with tubes and bandages in the night, and with stories about individual women who sold their sisters and their friends to the wazimamoto. For some women, wazimamoto stories were a way to describe the vulnerability of propertied women, the “special danger” faced by those women who lived alone. Most vampire stories were about extraction and agency; they showed the grim and mercenary motives of the colonial state, but in Nairobi these stories added another layer of agency and work to wazimamoto—women who worked for the firemen, capturing victims for them. They described a world in which relations of blood were easily expropriated and just as easily kept at bay.

| • | • | • |

Urbanization in Kenya

Perhaps the most significant way in which urban Kenya differed from rural Kenya even at the turn of the century was that women could own huts in the former but not in the latter. The degree of that ownership was often compromised by a variety of factors, such as the undermining of women’s Koranic inheritance in early colonial Mombasa by an amicable combination of their relatives and the colonial state, but wherever women’s property ownership was allowed to occur, women clung to it by whatever means were at their disposal.[1] Women’s property ownership under colonialism was markedly different from what they had had before: in the “house property complex” of South and North-east Africa, the land a women farmed was distributed to her sons and she had custodial rights over the livestock destined for them as well.[2] But as early as 1899 in eastern Kenya, when no legal system actually governed the area, twenty-five Maasai “loose women” built huts and were taxed on them by the Imperial British East Africa Company.[3] A few years later in Nairobi, women built huts, divided them into rooms, and lived in one and let the others at high rents. Within a few years, women were speculating in the city’s burgeoning property market.[4]

The question this chapter addresses is not how women achieved this, but how women talked about it, and how they constructed a world of fears and fantasies that imagined the possibility of women’s property ownership. Indeed, this is the only chapter in which all the vampire stories are taken from oral interviews. Stories about blood, about who had it and who wanted it, and how it was obtained and purchased, were stories about concrete relationships; the fluidity and intimacy of blood meant that fluid relationships could be made solid when expressed in its vocabulary.

Historically, women had a variety of strategies for controlling and directing the flow of resources— woman-to-woman marriage, the allocation of use rights from their matrimonial parcels of land, or using house property cattle for bridewealth to marry another woman.[5] Our knowledge of these strategies is severely limited because researchers have rarely inquired about them; no one seemed to wonder how sixty-year-old childless women managed their wealth. But colonial urban life offered the legal mechanisms—and the legal space—by which these strategies could become durable. Colonial courts, land offices, and arbitrary systems of land tenure provided rights that were not under the control of fathers and husbands and brothers. “At home, what could I do? Grow crops for my husband and father. In Nairobi, I can earn my own money, for myself,” said Kayaya Thababu, who went there in the mid 1920s.[6] Within the constraints of urban land tenure, women constructed rights for themselves and their heirs far beyond what they had been able to do previously.

But urban women’s property rights, delicate as they were, did not come about in a political vacuum. By the mid 1920s, half of Nairobi’s African property owners were women, almost all said to be prostitutes who had bought or built their houses with earnings from such work. Although the colonial state recognized the value of landlords who were also prostitutes—they had every reason to keep the peace, and their acquisitiveness kept labor circulating faster than pass laws did—officials were ambivalent about the social life that had emerged outside of colonial control, and the sense of community and stability it imparted to urban Africans in a city designed for European residence. The solution, worked out in committees between 1912 and 1915, was to allow Europeans freehold throughout the city and Africans usufruct in one small and poorly drained portion of it. In the official African location, Pumwani, finally established in 1921, plots could be transmitted to heirs but not bought and sold. The creation of one legal settlement made the two remaining African settlements illegal and had the effect of making housing in both places functionally usufruct, as few people were willing to buy houses that could be demolished at a moment’s notice. The threat of removal in Kileleshwa (demolished in 1926) and Pangani (demolished in 1939) meant that few Africans would be willing to buy houses there. The state’s ambivalence did not stop at usufruct, however: between 1912 and 1939, it made several attempts at landlordism, housing railway and municipal employees on their own estates, which rapidly became slums. Finally, the state borrowed the money to build an extension to Pumwani in 1939.[7]

The registration of land titles, even for usufruct housing in a city, offered new opportunities for women. Generally, in rural East Africa, husbands could negotiate their control over land whether or not they themselves farmed on it.[8] To give the Kikuyu example, men gave their wives gardens, from which their wives were obliged to feed them; children could take crops from their mothers’ gardens without permission, but not from their fathers’; men controlled the disposal of their own crops but not their wives’ surplus production. Fathers might give daughters a plot of land upon marriage, but they had to relinquish it to their brothers on demand. At marriage a man acquired for his wife a portion of his mother’s cultivated land. Men’s prestige—what John Lonsdale has called “civic virtue”—was based on how generous they were with land. Women essentially had usufruct rights to all the land they farmed, which they could extend to other women.[9]

Usufruct was thus nothing new to East African women. What became new, after 1921, was women’s ability to control usufruct rights through registration. Colonial legislation allowed for the ungendered registration of land. In rural East Africa, land registration was to become a specific political response to adult men’s vulnerabilities in land rights; it usually followed intense land speculation.[10] But the very fact of registration gave to local practices and strategies the power to name, and to mobilize, diverse social relations: in Nairobi in 1921, it allowed for durable rights of female inheritance and filiation.

How did women articulate their newfound control? They recounted the paperwork matter-of-factly, but they reported an anthropology of imaginary relations among themselves, townsmen, and firemen with passion and detail. Women told stories about how blood—sometimes their own, sometimes men’s—was redirected. Women in Nairobi described a natural history of new urban property rights with their own versions of stories about capture, penetration, and extraction—stories in which the men of the Nairobi Fire Brigade, black men employed by white men, captured people and removed their blood.

Stories about the wazimamoto began in Nairobi at the end of World War I. Most people said the practice ceased by the end of World War II. On the whole, men told stories about being captured, or almost captured, when they were out alone, and women told stories about the particular vulnerability they faced when they lived alone. These stories survived thirty and forty years after the events they described; indeed, in the late 1970s, these stories were told with excitement, enthusiasm, and care. Other rumors were not that important, and they did not last. A cursory reading of police informers’ reports from the 1930s and 1940s reveals some of the rumors no one remembered in the mid 1970s and 1980s: from 1939, that blankets were treated with a mysterious substance that would render men impotent, or that European doctors had perfected injections that would produce “bottled babies” without women.[11] Informers’ reports never mention wazimamoto, perhaps because informers did not believe these stories were rumors or loose talk. But vampire stories had their own histories in Nairobi, and died out there even as they were being told and retold in other parts of the country. Most of people said that the wazimamoto stopped taking blood in 1939, when Pangani, the oldest African settlement in Nairobi “was broken.” A few said it continued into the early 1940s and died out by 1942 or 1943.[12] Women who came to Nairobi during World War II heard that the wazimamoto sucked African blood; “but later I learned that they just put out fires,” Sara Waigo said. This chapter asks what was specific about Nairobi that generated such stories bound with such temporality and how women’s versions of these stories might disclose their conceptualization of urban space and its security and possession. For many years, oral historians have worried about the difficulty of establishing chronology from oral sources.[13] In part, I hope this chapter will interrogate that concern: does a distinct chronology alert researchers to local events and their sequence, or does it disclose local ideas and ideologies in precise ways?

When and where were women safe from vampires? Amina Hali, born in what was to become Nairobi in the 1890s, spoke of the time between 1921 and 1926, when the three settlements she names coexisted:

Not every woman who lived in the legal location of Pumwani thought it safe, however. Kayaya Thababu came to Pumwani in 1926. She described the skills and strategies of wazimamoto and how defenseless women were:Things were alright here in Pumwani but Pangani and Kileleshwa were dangerous places for a woman to live alone because she was in danger of being attacked by men from the wazimamoto.…they would come to Pangani and Kileleshwa in the afternoon and they would go with a woman, and pay her, and this way they would find out which woman lived alone and which ones did not, and they would come back at night and do their work.…these people carried sort of a rubber sucking tube that they would stick into your hands while you were asleep and draw the blood out of your body and leave you there, and eventually you would die.[14]

q:Other women simply negotiated with the wazimamoto: “They came when I was all alone and I told them there were people outside I lived with. I could not have told them I lived alone, otherwise they would have taken my blood and left me to die,” said Kibibi Ali.[16]Did you ever hear stories about wazimamoto?

a:Yes, they used to come in the night, they were a special danger to women who stayed alone, they would come into the room very softly and before you knew it they put something on your arm to draw out the blood, and then they would leave you and they would take your blood to the hospital and leave you for dead.

q:Couldn’t you scream for help?

a:They put bandages over your mouth, and also, these people who worked for wazimamoto, they were skilled, so if they found you asleep they could take your blood so quietly that you would not wake up, in fact you would never wake up.

q:Did this ever happen to you or one of your neighbors?

a:No but I heard about it a lot.

q:When?

a:Before the coming of the Italians [i.e., before 1940].

q:Were you frightened of them? How did you make sure they didn’t come to your room at night?

a:I was very frightened and there was no way to be sure they would not come, but when the fighting of the Italians ended they stopped coming for blood. But if you had a boyfriend staying with you at night you were safe, because they were afraid of waking two people.[15]

Nevertheless, living alone, especially in the legal location, gave some women some specific advantages. By the 1930s, many childless prostitutes—women who had lived alone—designated heirs to houses they had purchased or built in Pumwani. Usufruct gave to urban mud huts the same qualities as land: access to ownership could be secured through an intimate relationship. But even in Nairobi, women’s property rights were more problematic than men’s. According to a Muslim woman, Tamima binti Saidi, “It has always been difficult for women to inherit property, even in Pumwani the district commissioner had to be called in when a woman left everything to her daughter, even if she had no sons.” [17] Nevertheless, women in Nairobi utilized unwieldy state intervention to control their properties. For example, if a childless woman did not formally designate an heir “on the paper that allowed her to own the building,” then the Nairobi Municipal Council would “take over the building” when she died, becoming the owner and letting the rooms.[18] Yet many women did just that, bluntly rejecting kinship ties: it was by careful deliberation that they guaranteed that their property would not go to the families into which they had been born. Childless women most often designated as their heirs young women they had sheltered in town or brought from their rural homes. They were almost never blood kin, and to the best of my knowledge, the designated heirs were never males.[19] These relationships, between women of different generations, had specified rights and obligations and conferred specified duties and privileges. According to Tabitha Waweru, born in Pumwani in 1925:

Such filiations were as binding as ties of birth. But the various strategies by which such filiations were achieved were as dangerous as they were empowering. In the same interview Tabitha Waweru said that the wazimamoto employed prostitutes to find victims: “They didn’t just take blood from men; sometimes a prostitute would invite another woman to spend the night, and then the wazimamoto would come for her, for her friend.” [21]Some women were really rich, and when they became old, because they didn’t have any family living around Nairobi, that old woman could chose another woman and tell everyone “This is my heir.” She would have to love you, really, to do that for you, but it happened a lot. To become an old woman’s heir, you would have to cook for her, clean for her, wash her clothes for her, everything. Then one day this old woman will take the young woman to the DC’s office and say, “This is my daughter, I want her to get my property when I die”…and the DC would write it down; that’s how a lot of women got plots in Pumwani. A lot of women in Pumwani did this, they befriended old women, and they got property this way.[20]

How could a young woman know why an older woman befriended her? Would she be made an heir, or would she be sold to wazimamoto? The fact that both kinds of stories coexisted was not a contradiction; it was what was crucially important about them—both sorts of stories, frequently heard, depicted the complications of being female, alone, and propertyless in colonial Nairobi and the contradictory nature of any relationship that could bestow property within the law in the city. Indeed, these stories also reflected the contradiction by which filiation worked: in rural, patrilineal East Africa, mother-child ties could only be strengthened within the bonds of marriage, not outside them.[22] In Nairobi, mother-child ties were invented and inscribed without matrimony and very often without biological ties. Virtually all of these householders came from patrilineal societies; they were creating new relationships in a hard parody of uterine rights without marriages but with the equivocal support of the colonial state. Stories about the wazimamoto, with their formulaic Nairobi themes of tubes to extract blood, the invasion of space, and betrayal may have been more than cautionary tales of the perils of urban life. These stories may have provided a biological rationale for property inheritance that was not based on birth but superseded kinship ties. Stories about blood and the colonial state’s role in its removal may have made usufruct and the designation of heirs natural and legitimate.

| • | • | • |

Blood and Bone in East Africa

The blood of rubber sucking tubes, the blood drawn from the arm of sleeping women was perhaps a more specific bodily fluid than many East African peoples recognized, at least in the 1920s. As many chapters in this book argue, blood—the red fluid that flows through the body—was one of many fluids that Africans had, reproduced with, and shed in biological systems in which their circulation through the body was not a given. East African blood was the stuff of matrilineal inheritance; it was not specifically female, but it was thought of in opposition to semen, which was the stuff of male inheritance. The terminology is tricky, as semen itself was sometimes talked about as a kind of blood specific to men. But theories of gender and gestation explained how babies were made; they do not provide an exact gendered identity of fluids: among the patrilineal Teso, blood and bone are opposites; fathers contribute form to the fetus. But among the patrilineal Zande, a child is formed from its mother’s blood, as are children among the matrilineal Kaguru.[23] This is not to say that East African peoples make the same associations between blood and maternal inheritance; instead, it may be more accurate to say that some systems of kinship foreground this idea, while it is in the background of other systems of kinship. But systems of kinship were not the only systems of blood ties. Mixing male blood with another man’s blood could create intimate relationships among men: blood brotherhood signified intimacy both where blood was a metaphor for kinship and where it was not.[24] In Bunyoro, it was said that men achieved with blood pacts what women achieved through marriage; an Ankole ceremony announced: “Your blood brother cuts your nails.” [25] Nineteenth-century blood brotherhood ceremonies in East Africa collapsed boundaries between races and represented instant milk kinship. An 1894 ceremony between a European hunter and a Meru elder pantomimed that they had been nursed by one mother; in Bunyoro, the name for the ceremony of blood brotherhood was literally “drinking at the same place.” [26]

In nineteenth-century Kenya, exchanges of blood facilitated land sales. Litigants before the Kenya Land Commission testified that when Dorobo sold land to Kikuyu in the nineteenth century, the principals frequently became blood brothers. When they did not, the number of goats, rams, and steel tools exchanged increased substantially. Moreover, “when a man becomes the blood brother of another, and is given a piece of land, that means that he is liable to protect him against anyone wanting to rob his land or his properties.” [27] Blood exchange thus secured property transfers that were not inherited and gave the participants a degree of responsibility and continued involvement that outright sale did not have. The penetration of body boundaries enforced land boundaries.

Blood brotherhood was men’s business; what women—who shed another kind of blood regularly—thought of the institution has not been of much concern to a century of foreign participants and observers. But in many parts of East Africa, the power of women’s blood, in menstruation and childbirth, was fearsome, while the impact of men’s blood was considerably tamer—it made business transactions more personal and made men intimates. If blood brotherhood did indeed wane in the colonial era—and the evidence for this is anything but conclusive—it was not for lack of business transactions. Men reported entering into blood brotherhood to secure commodities, safe passage, and the like. The ceremonies may have lost their bodily specificity and imagery, but they were no less binding. Indeed, blood brotherhood became the domain of healers and contractual relationships.[28]

The biological assumptions on which blood brotherhood rested, the metaphors and beliefs that made it a rational way for men to conduct their business, were based on ideas that explained the relationships and biologies people saw every day. When Africans began to initiate other relationships of body, inheritance, and place, new metaphors and beliefs emerged. Put somewhat differently, the ways in which Africans described their ability to manage blood and control its flow—and the tense biology of relationships and possessions that blood represents—shifted in the colonial era.

| • | • | • |

Pits and Place in Pumwani

When Pumwani was, after much fanfare, established in 1921 as the only legal place Africans could live in Nairobi, plots were allotted to those Africans who could build huts on them within two months. Such a policy favored those who had owned property in the older settlements; they were allowed to own shops; others were not. All new householders paid an annual plot-holding fee. The earliest wazimamoto stories I have collected come either from the villages that were not demolished to populate Pumwani or from the streets of the city best known to workingmen. Before 1925, River Road—the street that linked central Nairobi to the African areas—was said to be the most dangerous place for men, “especially the job seekers.” [29]

Well into the 1930s, forest separated the nascent white suburbs from the central city, in which specific areas zoned for Indian residential and commercial use were established in the early 1920s only after Africans had been driven out of them. Men knew the spatial arrangements of the city and why they were in place: “These stories started in Nairobi when racial segregation was also there.” [30] Indeed, the legal status of land formed the background to 1920s wazimamoto stories from Nairobi: Kileleshwa, built on crown land—which legally belonged to the king, not the colony—and was demolished to make an arboretum in 1926, was one of the places where women were most vulnerable, while others said that victims’ bodies were buried in Kibera, a settlement of Nubian soldiers also on crown land. According to Timotheo Omondo, kibera was a Luo word for people who were “silenced in a sad manner”; the Nubian community were “not required to express their opinions” about who might be buried in there.[31]

But Nairobi in the early 1920s was also a city with a severe labor shortage. Men looking for work were free to traverse the city: “In the olden days there was no helping someone find a job. People used to go anywhere to ask for jobs.” [32] Despite the pass laws introduced in 1919, working men claimed they feared only agents of the wazimamoto who would lead them “to somewhere nobody knew,” where the wazimamoto would suck their blood.[33] The idea of specific places that were beyond African control, or sometimes beyond African knowledge, figured prominently in men’s vampire stories from the 1920s: a “town toilet” in River Road was notorious for wazimamoto abductions and known to migrants throughout the region. A man who worked in Nairobi was said to have seen a small room next to the toilet to which captives were taken.[34] A man in Dar es Salaam gave its exact location: on River Road near the Bohora Mosque, behind where the “Zima Moto” stayed, was a toilet men could only use with permission, but where a man from Kavirondo disappeared; even his brother could not find him.[35] Others said captured Africans were “driven to a secret place” where their blood was sucked with rubber tubes.[36] No woman my research assistants or I spoke to knew of such places; women in Pumwani only began to fear public toilets in the late 1930s. After 1937 or 1938, the toilets women feared were a generalized site of vulnerability, without location or specificity or even very detailed description: “The wazimomoto would come at night and climb over the wall and pounce on you if you were alone,” Hadija bint Nasolo said.

q:Prostitutes did not speak of the wazimamoto lurking in “places that looked empty” until the early 1940s.[38] Before the late 1930s, however, women’s wazimamoto stories described the mastery of space and time and the ambiguity of personal relationships.What wall?

a:The wall of the toilets, the wall of your room, any wall. If they found you alone they would draw your blood and leave you dying, even if you screamed there was nothing that could save you once they started to draw your blood.…Once when I and two friends entered a latrine, I was the first to finish…and came out first, alone. Just five yards away was the wazimomoto car with some men standing beside it, and when they saw me they started calling me and I started screaming…my friends came out at once and the wazimomoto men went away.[37]

In the 1920s and 1930s, women in Pumwani and Pangani lived with an anxious geography of hours and habits. Only Timotheo Omondo reported that he had been accosted by the wazimamoto “at roughly nine o’clock at night.” Not only did he recall the imprecision of his memory, but he described a near-capture, not his knowledge of how to outwit the firemen. Careful women could learn to avoid dangerous situations, which were animated at specific hours. Women who were prostitutes claimed that it was dangerous to go out after 6:30 at night, 8 at night, or 10 at night. They claimed that certain shops—owned in both Pangani and Pumwani by plot-holders until the mid 1930s—were dangerous. In Pangani, where a milk merchant was said to work for the wazimamoto “we would never send children to the shops after 6:30 at night.” [39] But in Pumwani in the 1920s, “from 8 o’clock in the evening nobody could go out for fear of meeting them.” [40] By the late 1930s, according to Miriam Musale, “In Nairobi the government used to tell people not to go out after 10 o’clock at night and if you didn’t listen it meant you didn’t care if you lived or died.” [41]

What are all these references to time about? Precise attention to time discipline does not usually characterize colonial African social life; indeed, without clocks how did Africans in an urban location tell time at night? Were these women simply observing that the wazimamoto operated in a world defined by the specifics of employment—a world of hierarchy, uniforms, and hours? Nairobi’s firemen may have straddled the boundaries between formal and informal work, however: on the one hand, firemen were put to the most routine work, polishing equipment and standing watch. On the other, they responded—at least in theory—to emergencies and put out fires, work that was different—and at a different time—each time they did it.

Nevertheless, exact timekeeping was a characteristic of urban wage labor, and the formalized ways in which men’s days were subdivided and controlled would have influenced how women organized the domestic tasks that reproduced wage labor. But many men resisted the precision of labor discipline and did not show up for work at the hour specified by their employers. Most women interviewed in Pumwani described men’s employment as a general condition of the male life cycle, not of hours, at least until the early 1940s: men “used to work, except for the young boys who couldn’t find work.” [42] When women had been formally employed, primarily during World War II, they were paid by the task, not by the hour.[43] It is possible that these references to hours may have represented colonial curfews—10 P.M. in Pumwani—but it is unlikely: while most prostitutes acknowledged the dangers of arrest, none mentioned the curfew, which seems to have existed only on paper. The only curfews that were enforced were those of wartime, which applied to men as well as to women.[44] It is altogether possible that the specificity of hours was an aspect of these women’s recent lives that they simply fed back into their memories, or that these women may have been illustrating the “islands of timekeeping” that distinguished Nairobi from rural East Africa and subjected it to new rules and imagined events.[45] In that case it would be important to ask why they associated precise hours with wazimamoto and not with other activities, such as cooking or their own prostitution? It is possible that many of these women simply used specific hours as a way to make sure that an otherwise naive researcher understood their point, that the wazimamoto operated after dark. They were using the specificity of time to describe urban life. But then, why did some women identify the dangerous hour as 6:30 and others as 8 or 10, and why did others describe wazimamoto activities in terms of minutes?

These references to time in Pumwani wazimamoto stories may not simply be about time discipline and the place of wage labor therein; they may allude to menstruation, or at least women’s blood. Many thought that the wazimamoto preferred women victims: “Women had the most blood. They give birth many times, each time losing a lot of blood, but still they are strong,” said Anyango Mahondo.[46] What is constant in these accounts is an hour, not any specific hour, indicating that periodicity was important: the wazimamoto was predictable. These women may not have been describing the time discipline of firemen, but that the firemen wanted women’s time-disciplined blood in particular. For most women in early colonial East Africa, menstruation had been an asocial experience. Many women claimed to have been surprised by menarche.[47] Adult women maintained some version of seclusion during menstruation: “During your periods you were not allowed out of the house for three days.” [48] “You took care to see that a man could never see anything; we took care ourselves.” [49] When childless women owned property and chose their heirs, menstruation may have lost some of its mystical significance, and it became subject to the same mundane laws that had come to govern everything else in Nairobi. “When prostitutes were menstruating…they would take the money they had saved from selling their bodies and buy this cotton.…At that time they would only sit and the money which they had saved would keep on feeding them until their period ended,” Margaret Githeka said.[50] Vampire stories that claim knowledge of timekeeping may assert that women could keep their blood safe from expropriation if they stayed indoors at specific hours of the night. If some spaces were beyond Africans’ knowledge, time did not have to be unmanageable as well.

Spaces, however, were unpredictable and appeared in unlikely places. Pits were commonplace in East African vampire stories. In Uganda, even an educated modernizer like E. M. K. Mulira knew about Mika, for example:

He had a big house and in one room was a big pit and on the pit there was a mat and on the mat there was a chair. He would take his friends and say, ‘You’re my special friend and I want to show you this wonderful thing I have, go into that room and sit on the chair, I’ll be right there.’ The man would go sit on the chair and fall straight into the pit, and then the bazimamoto would come and take his friend.[51]

Women knew about the shopkeeper in western Kenya who had a pit behind his premises.[52] Men knew about a farmer who trapped victims in pits until the wazimamoto could come and get them.[53] Anyango Mahondo described the pits beneath the Kampala Police Station, where captured Africans were kept “just like dairy cattle.” The pits had been domesticated to hide their dreadful purpose: “To hide the whole thing from everyone the entrances were covered with a carpet…even those working within the police station could not notice them. All they could see were only small but separate houses.…Inside the pits, lights were always on whether it was daytime or night.” The Nairobi Fire Station and the Dar es Salaam Fire Station were said have pits: “Whoever was inside the pits was never allowed to see the sun shine.” [54] Between the 1930s and 1960s, white prospectors, surveyors, and geologists—men who dug pits—were accused of being agents of wazimamoto; most were feared and some were attacked.[55] In 1920s Nairobi, pits were a social phenomenon. One part of Pumwani was known as Mashimoni, meaning “many in the pits” from shimo, the Swahili term for pits, hole, or quarry. It was said Mashimoni got its name because so many of the men who went there in the 1920s were never seen again. In a 1976 interview, Zaina Kachui, who arrived in Pumwani in 1930, explained why:

I heard that a long time ago the wazimamoto was in Mashimoni, even those people who were staying there bought plots with the blood of somebody. I heard that in those days they used to dig the floors very deep in the house and they covered the floor with a carpet. Where it was deepest, in the center of the floor, they’d put a chair and the victim would fall and be killed. Most of the women living there were prostitutes and this is how they made extra money, from the wazimamoto. So when a man came for sex, the woman would say, “Karibu, karibu,” and the man would go to the chair, and then he would fall into the hole in the floor, then at night the wazimamoto would come and take that man away. When they fell down they couldn’t get up again.…The wazimamoto were white people, but the people who worked to kill people, these were African, but wazimamoto employed the prostitutes who lived in Mashimoni because it was easy for these women to find blood for the wazimamoto because there were so many men going to Mashimoni for sex. They did this for the money, they needed the money, and they could do this kind of work.

Even if this was a story she told with equal conviction in the 1930s, it is unlikely that she told it to discourage men from frequenting Mashimoni: Kachui made it clear she was repeating hearsay. Besides “after a while men stopped going to Mashimoni because the wazimamoto worked there,” and by 1931 or 1932, Mashimoni had been eclipsed by the new “market for prostitutes” of Danguroni.[56] It seems more likely that this story reveals more about strategies of blood and filiation than it does about prostitutes’ strategies. The carpet—called by the most commonplace word for a woven mat (mkeka, for sleeping or prayer) represents the extent of a woman’s control over space, its possession, and how space is hidden, and privatized. Indeed, the woman who digs a deep hole in a small rented room and covers it with a man-made fiber is literally undermining the limits of rented accommodation; she is subverting her legal relationship to property as she alters it to appropriate men’s blood. The chair on the carpet covering the pit remains suspended, but when the man falls into the hole “he cannot get up again”: women have mastered these spaces and men have not. Indeed, women could do something with this space that men could not do.

Women could dig pits. The holes in prostitutes’ rooms articulate not only the women’s awesome control over their own residences but the fact that the differences between urban men and urban women—or working men and working women—were such that they could not be contained or depicted on one level. The construction of a literal spatial hierarchy articulated new relationships. Such a construction is even more significant for anyone concerned with blood, which flows downward: in many parts of East Africa, from the western Rift Valley to the plains of Tanzania, women were forbidden to climb on a house or step over a man, for if men were beneath women’s genitals, blood could fall on them.[57] What can it mean in another context, where space and intimacy are managed differently, for a woman to stand above a trapped and doomed man? In East and Central Africa, menstrual blood was thought to pollute the homestead.[58] When women control their own homes—at the very least, to the extent of excavating them—how then can a home be protected and be made safe for those who are female? What ideas about blood have to change for women and property to be safe in homesteads owned by women? Stories about pits in Mashimoni, where women “bought plots with the blood of somebody,” assert that a woman can be above a man, that menstrual blood does not pollute homesteads, but in fact gives women unique and specific ways to possess real property.

This is more than an account of the alteration of space, however; it depicts the alteration of space for a specific purpose—to drain men’s blood. The context is sexual; indeed, it is the availability of sexual relations for money that brings men to Mashimoni. These particular pits reverse the connotations of sexuality; they make men penetrable and unable to acquire property; pits indicate that in Pumwani inheritance could be separated from biological reproduction. In Mashimoni, property did not pass from males or to males; men passed through property and into the structural oblivion of pits. If blood—male and female—refers to maternal inheritance, then motherhood was redefined in Mashimoni: there, property did not pass through women to men, and women did not protect men’s property. Women used their property to dispossess men.

The pits in small Pumwani rooms, like the pits in colonial buildings and stations, did not exist. It is therefore important to note how differently they are described by men and women. Women described pits as places and sites; men’s descriptions of pits tended to have an extraordinary level of detail and commentary. The pits beneath the Kampala Police Station were so intricate because “whites are very bad people. They are so cunning and clever.” The subterranean pipes and taps were known only to Nairobi’s firemen: “Whites were very clever. They used to cover the pipes and taps with some form of iron sheets.” [59] The covered pits—covered with mats, huts, whatever—were subterranean systems that could be entirely closed off from the world above. This in turn suggested what was below the surface, suggestions animated by local connotations of what knowledge was hidden and suppressed.[60]

Time, property, and social reproduction were reversed in these pits. The many references to how the pits were illuminated suggest more than the deprivations faced by the victims of wazimamoto; in these accounts, working men described places where the ability to reckon time was taken from them.[61] Pits commoditized men; they became “just like dairy cattle.” In each of these examples, the site of underground production was made familiar by making it horrific, intricate, and timeless. Throughout the 1920s, “the place nobody knew” was no less fearsome, but it was made familiar by these repeated descriptions. The clever whites may have been able to hide fantastic spaces, but Africans—particularly those in secure occupations—could find out about them and talk about them.

In central Kenya, however, pits were not merely symbolic spaces, they were boundaries: they marked the limits of acquired property, and they made it private, or they separated one family’s territory from another’s. The social and physical imaginings pits animated came in part from their historical meaning in land transactions. According to Dorobo elders, the same men who sealed land transfers with blood brotherhood in the nineteenth century, “the general way of marking out a boundary was to show the purchaser our game pits and tell him which ones he could not pass.” [62] To the north of Dorobo country, Kikuyu marked boundaries with streams and valleys. Where the landscape had no distinguishing features, the landscape could be altered or body products used to mark boundaries: people planted trees, heaped stones, or buried human hair. As late as the mid 1950s, boundary-making was men’s work.[63] When Africans told stories about clever white men digging pits in public places or African women digging pits in their rented rooms, they were not only describing the expropriation of land by Europeans and women, but their expropriation of African men’s rights to limit that expropriation. If rights over land can only be maintained with a distinct vocabulary of technical sophistication, as H. W. Okoth-Ogendo argues,[64] then pits and blood would seem to have become part of a specialized East African vocabulary in which rights to land were debated and defined. Without pits, women luring men or women to their rooms were simply working for wazimamoto, not asserting rights over land and its transmission.[65]

| • | • | • |

Discarding Blood

Many prostitutes, including property owners, did not tell stories in which men were the victims of the wazimamoto; they told stories in which women were. Just as single women’s property in Pumwani was transmitted to adopted daughters, sisters, and sisters’ children, single women told stories in which young girl visitors, friends, and sisters were sold to the wazimamoto by prostitutes. Just as I know of no case where a prostitute designated a man as the heir of her house, I know of no case where a woman was said to have sold brothers, brothers’ sons, or male friends to the fire brigade. Many prostitutes did sell their customers, of course, but that was part of their work: according to Tabitha Waweru, sometimes a prostitute “would see a man, invite him in, feed him, sleep with him, and when he’s asleep the wazimamoto would come and take him.” Women sold women with as many courtesies, but they described the process and its emotional content with considerably greater detail.

Why were women both agents and victims? Why did women’s stories make female friendship, even female kinship, not only terrifying, but lethal? In a place where women befriended each other and passed property to each other, and sometimes to sisters or sisters’ children, why did women tell stories in which women sold their women friends, their sisters, and their sisters’ children to the wazimamoto? The question implies that Pumwani prostitutes should identify either with the agents or the victims, that they should tell stories that were much less ambiguous than their urban social and property relations were. Storytellers reshape hearsay into what is familiar; popular stories reflect the contradictory nature of relationships and the possibilities that constitute those relationships.[66] Sisters’ daughters and close friends—all potential heirs in interwar Nairobi—were powerful relationships in Pumwani. Relations with male friends, brothers, and to a lesser extent sisters’ sons, did not convey the same power, the same kind of inheritance, or the same degree of social reproduction. It is entirely possible that these stories survived because the tellers and the listeners acknowledged the ambiguities of kinship and friendship. Women in Pumwani in the 1970s articulated the strains and contradictions of those relationships with each retelling of these stories.

These contradictions were lived, and they were remembered with a specificity of names and durations and rewards. Hannah Mwikali, who came to Pumwani in the mid 1920s, identified one Mama Amida, “the first woman to build a brick house in Majengo,” who “sold her sister’s daughter to the wazimamoto for money although later they came for her too.” [67] According to Mwana Himani bint Ramadhani, who came to Nairobi in 1930, prostitutes sold each other:

Muthoni wa Karanja, who lived in an illegal settlement, but who visited Pumwani regularly between 1935 and 1939, said “there was a fat woman named Halima and this woman sold her sister to these people but she was lucky enough to escape…before they finally captured her. They used to sell people for 50/- a person; no wonder these women could afford to build houses in Pumwani.” She claimed that the firemen themselves were very selective about their victims: “At 10 o’clock at night the wazimamoto came and looked for victims. They would throw rocks at doors until someone opened and then they would take whoever opened the door, unless it was a child, because children do not have much blood, not as much as an adult.” [69]When I first came to Nairobi…I used to fear to go visit my friend, a woman like me, because the wazimamoto would hire a black woman and when her friend came to visit she would find out if she was married or not, or if her family came to visit her, and then she would tell the wazimamoto when her friend would be coming again, and then, during that visit, maybe after ten minutes, thirty minutes, the wazimamoto would come and kill you.[68]

This specificity of detail is more than a devastating critique of the plotholders some of these women despised. These accusations are hurled at women who seemed to commoditize not only sexual relations but kinship relations and, almost as frequently, those of friendship. As such, however, these accusations are also descriptions, however violent and bloody, of the construction of families and the hierarchy of relationships and obligations that families represented. Firemen would not take a child, for example, because that child was evidence that its mother did not live alone. A woman would be called Mama Amida because she was someone’s mother; she would not leave her stone house to her sisters’ daughter.

The abandonment of kin and friends, the failure to animate the new relationships that Nairobi offered, became the focus of women’s disgust and disappointment. Years later, women conflated the disregard for blood ties with the disregard for the proper handling of menstrual blood. According to Zaina Kachui, who so forcefully described the pits in Mashimoni, “In the old days you wouldn’t let anyone see your blood, even if you had a boyfriend living in your room, he could not be allowed to see your blood, or bloody clothes. In these days you see bloody rags everywhere, in the streets and in the toilets; it’s the way I used to see dead babies in the toilets all the time.”

It was not only prostitutes who commoditized kin and discarded children and siblings. Between 1936 and 1939, the colonial state, after much hesitation, demolished Pangani and replaced it with an estate of its own devising: it offered former Pangani landlords lifetime leases on cement-block four- and six-room houses. The conditions of these lifetime leases allowed landlords to select tenants and charge rents competitive with those in Pumwani, but they could not pass on their property when they died, when their houses would revert to the City Council. The Pangani householders’ decision to accept the state’s offer was painful—the estate was called Shauri Moyo, literally “matter of the heart,” before it opened—but 90 percent of Pangani’s woman landlords accepted it, thus ending usufruct in one settlement and leaving landlords in Pumwani decidedly wary.[70] It is altogether possible that more women landlords would have gone to Shauri Moyo, but women who owned property as designated heirs were not eligible for relocation there.[71] Although some women landlords in Shauri Moyo tried to pass their houses on to their daughters or their designated heirs, their wills were rejected by the state, while popular history in Pumwani had it that the “rich women of Pangani” built houses in Shauri Moyo for themselves.[72] This local revisionist history of African housing in Nairobi held that Pangani’s women landlords voluntarily abandoned usufruct, thus abandoning not only their children but sisters, sisters’ daughters, and a whole network of friends and potential friends whose entitlement to property and access to land was all but curtailed in Nairobi after 1939.

Many women in Nairobi said that the wazimamoto stopped capturing people when Pangani was finally demolished. This may have been a convenient marker, but other events, such as talk of war with the Italians over the border, or the fire that destroyed the colonial secretariat buildings in town,[73] might also have been what was memorable about 1939 for prostitutes. It would seem that as the new, social meaning of Nairobi usufruct was effectively dislodged in 1939, stories about the wazimamoto removing the blood from women who stayed alone began to die out.

| • | • | • |

Conclusions

Stories about the removal of precious bodily fluids by some agency of the colonial state provided vivid examples of rapacious imperial extractions, should any have been needed in colonial Nairobi. But this chapter argues that when told, these stories did not describe Europeans’ unchecked power but Europeans’ weakness and dependence on the cooperation of African prostitutes. It is possible that the colonial state, with its “rubber sucking tubes” and its electric lights in pits, was the background for these stories, not the subject matter. The disdain with which the “clever whites” were condemned was part of the construction of an urban social world, but beyond the contempt and dislike were subtle and nuanced imaginings that described new orderings of household, gender, and property relations. Through the construction of a fantastic vision of European violence, Africans reported changes in their social life, their concepts of pollution and vulnerability, and their land tenure.

Notes

1. Margaret Strobel, Muslim Women in Mombasa (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1979), 58–69; Greet Kershaw, Mau Mau from Below (Oxford: James Currey 1997), 59, 126–27; provincial commissioner, Coast Province, to colonial secretary, Nairobi, “Legal Ownership of Huts by Independent Women,” 23 June 1930 (Kenya National Archives [henceforth cited as KNA], PC/Coast/59/4).

2. Jack Goody and Joan Buckley, “Inheritance and Women’s Labour in Africa,” Africa 43, 2 (1973): 108–20; Godfrey Muriuki, A History of the Kikuyu, 1500–1900 (Nairobi: Oxford University Press, 1974), 75–76; Achola Pala Okeyo, “Daughters of the Lakes and Rivers: Colonization and Land Rights of Luo Women,” in Mona Etienne and Eleanor Leacock, Women and Colonization: Anthropological Perspectives (New York: Praeger, 1980), 186–213; Margaret Jean Hay, “Women as Owners, Occupants, and Managers of Property in Colonial Western Kenya,” in id. and Marcia Wright, eds., African Women and the Law: Historical Perspectives (Boston: African Studies Center, Boston University, 1982), 110–23.

3. Harold Mackinder Papers, 20 July 1899, Rhodes House, Oxford, RH MSS Afr. r. 29.

4. Janet M. Bujra, “Pumwani: The Politics of Property” (mimeographed SSRC [U.K.] report, 1972), 9–13, 51–54, and “Women ‘Entrepreneurs’ of Early Nairobi,” Canadian J. of African Studies 9, 2 (1975): 213–34; Charles H. Ambler, Kenyan Communities in the Age of Imperialism (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1988), 139–40; Luise White, The Comforts of Home: Prostitution in Colonial Nairobi (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990).

5. Christine Obbo, “Dominant Male Ideology and Female Options: Three East African Case Studies,” Africa 46, 4 (1976): 371–88; L. S. B. Leakey, The Southern Kikuyu before 1903 (London: Academic Press, 1977), 800–801; Regina Smith Oboler, “Is the Female Husband a Man? Woman/Woman Marriage among the Nandi of Kenya,” Ethnology 19, 1 (1980): 69–88; Patricia Stamp, “Kikuyu Women’s Self Help Groups,” in Claire Roberstson and Iris Berger, eds., Women and Class in Africa (New York: Holmes & Meier, 1986), 27–44; Fiona MacKenzie, “Land and Territory: The Interface between Two Systems of Land Tenure, Murang’a District,” Africa 59, 1 (1989): 91–109; Ivan Karp, “Laughter at Marriage: Subversion in Performance,” in David Parkin and David Nyamwaya, eds., The Transformation of African Marriage (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1987), 137–54.

6. Kayaya Thababu, Pumwani, 7 January 1977.

7. White, Comforts of Home, 45–48, 51–78, 80–83, 126–46.

8. Okeyo, “Daughters of the Lakes”; Hay, “Women as Owners”; Henrietta Moore, Space, Text, and Gender: An Anthropological Study of the Markawet of Kenya (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986), 65–71.

9. Gretha Kershaw, “The Land Is the People: A Study in Kikuyu Social Organization in Historical Perspective” (Ph.D. diss., University of Chicago, 1972), 54–55; Peter Rogers, “The British and the Kikuyu, 1890–1905: A Reassessment,” J. African Hist. 20, 2 (1979): 255–69; Fiona MacKenzie, “Local Initiatives and National Policy: Gender and Agricultural Change in Murang’a District, Kenya,” Canadian J. of African Studies 20, 3 (1986): 377–401; John Lonsdale, “The Moral Economy of Mau Mau: Wealth, Poverty and Civic Virtue in Kikuyu Political Thought,” in id. and Bruce Berman, Unhappy Valley: Conflict in Kenya and Africa, bk. 2, “Violence and Ethnicity” (Athens: Ohio University Press, 1992), 315–504; Carolyn Martin Shaw, Colonial Inscriptions: Race, Sex and Class in Kenya (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1995), 28–59; Claire E. Robertson, “ Trouble Showed Me the Way ”: Women, Men, and Trade in the Nairobi Area, 1890–1990 (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1997).

10. M. P. K. Sorrenson, Land Reform in Kikuyu Country (Nairobi: Oxford University Press, 1967), 52–71; Robert Bates, “The Agrarian Origins of Mau Mau: A Structural Account,” Agricultural History 61, 1 (1987): 1–28. Gretha Kershaw, “The Land Is the People,” notes that land consolidation in Kiambu was not a reform of land tenure “but has become a statement about who had tenure and to what extent” (61n).

11. Central Province District Annual Report, 1939–41, 3 (KNA, PC/CP 4/4/1).

12. Celestina Mahina, Mathare, 14 March 1976; Esther Kimombo, Mathare, 9 June 1976; Sara Waigo, Mathare, 1 July 1976; Amina Hali, Pumwani, 4 August 1976; Salim Hamisi, Pumwani, 29 March 1977.

13. The classic critique is David Henige, The Chronology of Oral Tradition: Quest for a Chimera (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1974).

14. Amina Hali, interview cited n. 12 above.

15. Kayaya Thababu, Pumwani, 7 January 1977. The “coming of the Italians” refers to the 20,000 Italian prisoners of war captured in Ethiopia in 1940 and marched to Kenya, and to World War II, called in Swahili “the fighting of the Italians.”

16. Kibibi Ali, Pumwani, 21 June 1976.

17. Tamima binti Saidi, Pumwani, 15 March 1977; Thomas Colchester, former municipal native affairs officer, Nairobi, London, 8 August 1977.

18. Sara Waigo, Mathare, 1 July 1976.

19. White, Comforts of Home, 119–22.

20. Tabitha Waweru, Mathare, 13 July 1976.

21. Ibid.

22. Ivan Karp, Fields of Change among the Iteso of Kenya (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1978), 87–88.

23. Ivan Karp, “New Guinea Models in the African Savannah,” Africa 48, 1 (1978): 1–16; E. E. Evans-Pritchard, “Zande Blood Brotherhood,” Africa 6, 4 (1933): 469–501; T. O. Beidelman, “The Blood Covenant and the Concept of Blood in Ukaguru,” Africa 33, 4 (1963): 321–42.

24. Evans-Pritchard, “Zande Blood Brotherhood,” 397; Beidelman, “Blood Covenant,” 328; I have argued that blood brotherhood creates an idealized version of kinship between men; see Luise White, “Blood Brotherhood Revisited: Kinship, Relationship and the Body in East and Central Africa,” Africa 64, 3 (1994): 359–72. Mixing men’s blood and women’s menstrual blood was very risky, however: “When you have your monthly period and after you bleed for three days you then urinate a lot, and if during those days after you go with a man whose blood does not match yours then you will develop kisonono [gonorrhea],” Amina Hali said (cited n. 12 above).

25. J. M. Beattie, “The Blood Pact in Bunyoro,” African Studies 17, 4 (1958): 198–203; F. Lukyn Williams, “Blood Brotherhood in Ankole (Omukago),” Uganda Journal 2, 1 (1934): 33–41; White, “Blood Brotherhood Revisited.”

26. Ambler, Kenyan Communities, 83; see also Williams, “Blood Brotherhood in Ankole,” 40–41; Beattie, “Blood Pact in Bunyoro,” 198.

27. Kenya Land Commission, Evidence and Memoranda, (London: HMSO, 1934), 1: 285, 271, 329. It is unlikely that these Dorobo were Okiek misnamed by colonial authorities, inasmuch as the term incorporated a number of peoples living in the area; see Corinne A. Kratz, “Are the Okiek Really Maasai? or Kipsigis? or Kikuyu?” Cahiers d’études africains 79, 20 (1981): 355–85, and Affecting Performance: Meaning, Movement, and Experience in Okiek Women’s Initiation (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1994), 60; J. E. G. Sutton, “Becoming Maasailand,” in Thomas Spear and Thomas Waller, eds., Being Maasai, 38–60 (London: James Currey, 1993); and John G. Galaty, “‘The Eye That Wants a Person, Where Can It Not See?’: Inclusion, Exclusion, and Boundary Shifters in Maasai Identity,” in ibid., 174–94.

28. White, “Blood Brotherhood Revisted,” 268–39; Steven Feierman, Peasant Intellectuals: History and Anthropology in Tanzania (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1990), 174.

29. Timotheo Omondo, Goma Village, Yimbo, Siaya District, 22 August 1986.

30. Nyakida Omolo, West Alego, Siaya District, 19 August 1986.

31. Ibid.

32. Ibid.

33. Ibid.

34. Zebede Oyoyo, Goma, Yimbo, Siaya District, 13, 23 August 1986.

35. “Adiyisadiki” (“Believer”), letter to the editor, Mambo Leo, November 1923, 13–14.

36. Pius Ouma Ogutu, Uhuyi Village, West Alego, Siaya District, 19 August 1986.

37. Hadija bint Nasolo, Pumwani, 3 and 8 March 1977.

38. Gathiro wa Chege, Mathare, 9 July 1976.

39. Fatuma Ali, Pumwani, 21 June 1976; see also Bujra, Pumwani, 28–29.

40. Chepkitai Mbwana, Pumwani, 1 and 2 February 1977. Being late for work often maintained alternate systems of time-keeping and work discipline; see E. P. Thompson, “Time, Work Discipline, and Industrial Capitalism.” Past and Present 38 (1968): 56–97, and Keletso E. Atkins, “‘Kaffir Time’: Preindustrial Temporal Concepts and Labor Discipline in Nineteenth-Century Natal,” J. African Hist. 29, 2 (1988): 229–44.

41. Miriam Musale, Pumwani, 18 June 1976. Some women said it was 8 o’clock (e.g., Elizabeth Kaya, Pumwani, 17 August 1976).

42. Chepkitai Mbwana.

43. Zaina Kachui, Pumwani, 14 June 1976.

44. Chepkitai Mbwana; Kayaya Thababu; Miriam Musale; Zaina Kachui.

45. These points come from two very different studies of time-keeping, Pierre Bourdieu, “The Attitude of the Algerian Peasant toward Time,” in J. Pitt-Rivers, ed., Mediterranean Countrymen (Paris: Mouton, 1963), 55–72, and Nigel Thrift, “Owners’ Time and Own Time: The Making of a Capitalist Time Consciousness, 1300–1880,” Lund Studies in Geography, ser. B, 48 (1981): 56–84.

46. Anyango Mahondo, Sigoma, West Alego, Siaya District, 15 August 1986.

47. Zaina Kachui; Christina Cheplimo, Pumwani, 17 March 1977. “In Pumwani, you women were taken to a friend of their mother’s to explain menstruation” (Zaina binti Ali, Calyfonia, 21 February 1977).

48. Wangui Fatuma, Pumwani, 29 December 1976.

49. Asha Wanjiru, Pumwani, 23 December 1976.

50. Margaret Githeka, Mathare, 2 March 1976; Mary Salehe Nyazura, Pumwani, 13 January 1977.

51. E. M. K. Mulira, Mengo, Uganda, 13 August 1990.

52. Domtita Achola, Uchonga. West Alego, Siaya, 11 August 1986.

53. Nyakida Omolo; Nichodamus Okumu-Ogutu Uhuyi, Alego, 20 August 1986; Raphael Oyoo Muriar, Uchonga Village, Alego, 21 August 1986.

54. Salim Hamisi, Pumwani, 29 March 1977; Raphael Oyoo Muriar, Uchonga Village, West Alego, Siaya District, 20 August 1986.

55. E. E. Hutchins, DO, Morogoro, Morogoro District Book, vol. 1, August 1931. I am grateful to Thaddeus Sunseri for taking notes on this file for me. Darrell Bates, The Mango and the Palm (London: Rupert Hart-Davis, 1962), 47–55; “‘Witchcraft’ Murder of Geologist,” Tanganyika Standard 2 April 1960, 1; William Friedland Collection, Hoover Institution, Stanford University, Summary of Vernacular Press, Ngwumo, 4 October 1960; H. K. Wachanga, The Swords of Kirinyaga: The Fight for Land and Freedom, ed. Robert Whittier (Nairobi: Kenya Literature Bureau, 1975), 143; Peter Pels, “Mumiani: The White Vampire. A Neo-Diffusionist Analysis of Rumour,” Ethnofoor 5, 1–2 (1995): 166.

56. White, Comforts of Home, 86–93, 116–24.

57. T. O. Beidelman, Moral Imagination in Kaguru Modes of Thought (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1986), 35; Moore, Space, Text, and Gender, 181

58. Jean S. LaFontaine, “The Ritualization of Women’s Life-Crises in Bugisu,” in id., ed., The Interpretation of Ritual: Essays in Honour of A. I. Richards (London: Tavistock, 1972), 159–86; Leakey, Southern Kikuyu, 1: 163–66; 3: 1241; Thomas Buckley and Alma Gottleib, “A Critical Appraisal of Theories of Menstrual Symbolism,” in Buckley and Gottleib, Blood Magic: The Anthropology of Menstruation (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1988), 3–40.

59. Anyango Mahondo; Alec Okaro, Mahero Village, West Alego, Siaya District, 12 August 1986.

60. Peter Stallybrass and Alon White, The Politics and Poetics of Transgression (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1986), 140–51; Rosalind Williams, Notes on the Underground, An Essay on Technology, Society, and the Imagination (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1992).

61. This is E. P. Thompson’s point about factory design in the eighteenth century in “Time, Work Discipline, and Industrial Capitalism.”

62. Kenya Land Commission, Evidence, 1: 222.

63. Muriuki, History of the Kikuyu, 76; MacKenzie, “Land and Territory,” 99.

64. H. W. O. Okoth-Ogendo, “Some Issues of Theory in the Study of Tenure Relations in African Agriculture,” Africa 59, 1 (1989): 6–17.

65. In 1950s Dar es Salaam, according to Lloyd William Swantz, “The Role of the Medicine Man among the Zaramo of Dar es Salaam” (Ph.D. diss., University of Dar es Salaam, 1972), 337, it was said that several women of the Tanganyikan African National Union’s Women’s League would entice men to their rooms and take their blood; they were said to be employees of the fire brigade.

66. Janice Radway, Reading the Romance: Women, Patriarchy, and Popular Literature (Chapel Hill, N.C.: University of North Carolina Press, 1984), 119–45; see also Beidelman, Moral Imagination, 102–3, 116–9.

67. Hannah Mwikali, Kajiado, 8 November 1976.

68. Mwana Himani bint Ramadhani, Pumwani, 4 June 1976.

69. Muthoni wa Karanja, Mathare, 25 June 1976.

70. White, Comforts of Home, 132–46.

71. Miriam binti Omari, Pumwani, 25 March 1977.

72. Hadija Njeri, Eastleigh, 5 May 1976; Sara Waigo, Mathare, 1 July 1976.

73. Nairobi Municipal Council Minutes, 18 September 1939 (KNA/PC/NBI/2/54).

6. “Roast Mutton Captivity”

Labor, Trade, and Catholic Missions in Colonial Northern Rhodesia

This chapter and the one that follows are based exclusively on written evidence. Rather than suggesting that written accounts of oral phenomena lose a great deal in transcription and translation, I argue that the very messiness of documentary evidence allows for an analysis of bundled ideas, of the contradictions and confusions of colonial thinking, and the economies, justifications, and policies that thinking created. Unlike chapters 5 and 8, in which oral evidence provides a sequence of who knew what about whom, and where they knew it, in these chapters there are no layers to unravel, no final insights that stripping away images and ideas can promise. Indeed, the written evidence used here is dense and disorganized—priests’ accounts of African ideas about coins and their value follow reports of a strike by catechists, for example. For all the chronological clarity of written sources, the very density of these accounts suggests relationships that, taken together, show what rumors meant on the ground in the colonial Northern Rhodesia.

| • | • | • |

Gossip and Authority

When I was a girl I was taught not to gossip by a school game: we would sit in a circle and someone would whisper a phrase into the ear of the person sitting next to her. By the time the phrase was returned to the first speaker, it was totally deformed—hilarious proof that hearsay distorted facts. I had already published a book based extensively on oral interviews when I realized how insidious this game was, that it rested on two extremely authoritarian principles: that information should be transmitted passively, and that no one has the right to alter or amend received statements.

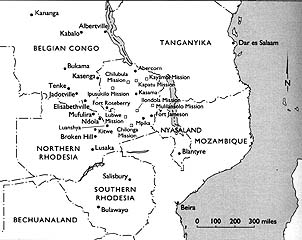

Map 2. The Belgian Congo and Northern Rhodesia

Real life and real gossip and rumormongering are substantially different, however. The purpose of gossiping, rumormongering, and even talking is not to deliver information but to discuss it. Stories transmitted without regard for official versions, stories that are amended and corrected and altered with every retelling, are indeed rumors, but they are also a means by which people debate the issues and concerns embodied in those stories. In a historiography based on such stories, then, there is no one true or accurate version. It is precisely the fact of many variants that is crucial to our understanding the meaning of these stories. Each one, taken on its own, may be interesting and suitable for analysis, but taken together, they form a debate, public discussions and arguments about the issues with which ordinary people are concerned. And, more important, these stories were taken together: they were neither told in isolation nor recounted without contradiction or correction. There was no single established version; there was no single accurate account. Instead, these stories were told, exchanged, criticized, refined, and laughed at—they were part of public knowledge, a way to argue and complain and worry. Taken together, the stories I shall discuss articulated why Africans should have been concerned about the motives and activities of certain groups, whether firemen, tsetse-fly pickets, game scouts, or Catholic priests.

This chapter explores why one congregation of Catholic missionaries was accused of drinking Africans’ blood. It is not a conventional historical narrative. Not only will it lack a beginning, middle, and an end, it will not attempt to tell a coherent story. If vampire accusations have multiple meanings, one chapter in this book should have multiple endings. What follows are three sets of evidence—some historiography, the accusations, and the economics of the missions—and four separate interpretations of the accusations. My goal is not to explain these particular vampire accusations, but to contextualize them, and show how they might be interpreted to form a debate about the priests’ ritual and daily practices. My concerns are not about popular culture as most twentieth-century African historians understand it—music, oral literature, and street wisdoms of various sorts—but about popular debates about ideas: the meaning of sacrifice, food, and blood, and tensions over work and its remuneration.[1] These questions were engendered in the most formal of settings—in schools, during Communion, and in the workplace—but they were debated in a popular form, rumor and gossip.

| • | • | • |

Evidence: Zambian Historiography

This chapter is part of a revision, or at least erosion, of the conventional wisdoms of the history of Zambia that has been going on for a decade. The Northern Province of Zambia (colonial Northern Rhodesia) was historically the catchment area for the mines of Katanga in the then Belgian Congo, the Zambian Copperbelt, and the Lupa Goldfields in southeast Tanganyika. It has been considered a classic labor reserve: rural poverty sent men to the mines, from which they returned when they had earned some money. Copper had been smelted from malachite in the region long before European rule, but new industrial technologies made the copper sulfides found far below the surface accessible. The first mine in Katanga opened in 1906;[2] well into the 1920s, a large proportion of the migrant labor force was from Northern Province.[3] In colonial Northern Rhodesia, there were mines owned by European prospectors as early as 1902, but the development of the Copperbelt there did not begin until 1922 and did not take off until 1927, when there were about 9,000 men employed there. By late 1930, however, there were almost 32,000 Africans working on the Copperbelt.[4] Starting in the 1920s, labor from Northern Province was recruited for both mining and plantation work in Tanganyika; because sisal wages were higher and more reliable, workers tended to stay three years on the sisal plantations of Tanga but an average of six months in the Lupa Goldfields.[5]

Africans’ rural experience was represented by Europeans as one of intense demands for African labor. The diaries of the White Fathers (the Société des Missionnaires d’Afrique) are filled with references to visits by labor recruiters from the Lupa Goldfields, from Copperbelt mines, and from the Union Minière d’Haute Katanga, asserting the inexorable attraction of wage labor: “Recruiters come by car from Ndola and with their promises entice them, hiring a number of workers, whom they transport without charge to the mine. How can the blacks, like big children, resist this?” [6] Men did stay away from the countryside. Even during the Depression—when the number of workers on the Copperbelt dropped from 31,941 to 19,313 by late 1931 and to 6,667 by the end of 1932—many men did not return home, although some went to look for work in Katanga or South Africa.[7] Audrey Richards claims that 40 to 60 percent of Northern Province men were absent from their villages in the early 1930s, although these men were not all working; many were looking for work.[8] James Ferguson, following A. L. Epstein, has challenged the picture of male migrants temporarily working in towns but without urban ties, and has argued that between the 1930s and the 1950s, workers’ movements between urban jobs, and between jobs at a single mine, were at least as commonplace as were workers’ periodic returns to the countryside.[9] Those men who stayed on the Copperbelt during the Depression looked for work and articulated their need for employment in terms of status and community, not just livelihoods. In 1933, the leader of a Bemba workers’ association went to the capital to protest unemployment and low wages: “People like me can’t go home,” he said. “We have settled in the towns, adopted Europeans’ ways, and no longer know village life.” [10] It was not only European ways that made the Copperbelt attractive to Africans; Africans could be hired as skilled labor there as well. By 1935, a white South African trade unionist worried that Copperbelt Africans were already breaching “the sacrosanct line” between unskilled and skilled mine labor.[11] Wage labor seems to have had some advantages for colonial Northern Rhodesians; there was the possibility of advancement, and when there was no work, men could go to Lusaka or Southern Rhodesia and work as domestics.[12]

The peoples of Northern Province, primarily Bemba, practice a slash-and-burn agriculture called citemene. According to Audrey Richards’s painstaking research in the early 1930s, the sexual division of labor of men cutting down trees and clearing land and women planting and harvesting crops and preparing food was disrupted by the demand for male labor on the Copperbelt and in Katanga, and this created “the hungry months” of February, March, and April: there were not enough men to clear fields sufficient for their families’ needs. But Henrietta Moore and Megan Vaughan have argued that citemene was not the main food-producing system among the Bemba; hoed mound gardens were, although tending them was “considered hard and unromantic work by the Bemba.” [13] Indeed, the White Fathers raised tribute for boarding school students based on the number of mound gardens a village had.[14] According to Vaughan and Moore, seasonal food shortages were due, not to the size of women’s citemene gardens, but to the combination of women’s domestic and agricultural tasks at certain times of the year. Women would have faced this seasonal burden whether men were present or not.[15] In the village of Kasaka in 1933, for example, Richards found a ratio of 19 men to 23 women, in her opinion enough men to clear adequate citemene gardens. Food supply was not an issue in Kasaka; women’s work was: Richards’s daily records show that when women’s agricultural labor was particularly heavy, they neglected some time-consuming domestic tasks, such as gathering and cooking, so that “the natives’ diet may be inadequate in certain seasons of the year because the housewife is too busy to provide proper meals.” [16] It would seem that absent men shaped their families’ needs and expectations and ideas about work and money, not their food supply. But the extent of a sexual division of labor in which men migrated and women farmed became the lens through which officials and academics saw Bemba society.

This chapter explores African ideas about the meaning of work, money, food, and to a lesser extent, religion, through vampire accusations. In doing so, I use European sources almost exclusively—the diaries of Catholic missions and district officers’ reports. These texts were not produced in identical circumstances, however. The priests produced two kinds of documentation, the Annual Reports of their order, published by the Mother House in Algeria and the daily diary of each mission station. The Annual Reports are straightforward, if somewhat anguished, records of African affairs—labor recruitment or religious revivals—while the diaries provide a remarkable chronicle of the daily life of the mission. Like many diaries, these record everyday events, and they do not always elaborate on what was well known to the priests themselves. The diarists were more concerned about official support for Protestant missionaries than they were, for example, about the anti-Catholicism of Watchtower after 1920, of which the priests were fairly tolerant.[17] I do not claim to ferret African voices out of these texts, however. I simply use European sources about vampiric priests to reveal African ideas about blood and the issues for which blood was a potent metaphor in the Northern Province of Northern Rhodesia.

| • | • | • |

Evidence: Vampire Accusations

Between the mid 1920s and the mid 1950s, charges that Africans working for Europeans captured other Africans for their blood were commonplace in Northern Rhodesia’s Northern Province. In almost all the accusations, these African vampires went by the generic name banyama. But in almost every outbreak of these accusations that came to the attention of colonial officials, one order of Catholic priests—the Société des Missionnaires d’Afrique, known in Africa and among themselves as the White Fathers, because of their robes— were identified as some of the Europeans behind the banyama.

Between 1928 and 1931, there were periodic panics over banyama in the Kasama District of Northern Province. In some areas it is said, probably with great exaggeration, that no African would go out alone. It was frequently said that the provincial commissioner had met with the Chitimukulu, paramount of the Bemba, to pay him to allow banyama into his country. The White Fathers claimed that “the natives believe that there are two Banyama at Chilubula [their station in Kasama District] whose names are unknown, and that anyone from the mission is accordingly treated with suspicion.” White Fathers both at Chilubula and Ipusukilo, in Luwingu, advocated “strong repressive measures.” [18] In 1932, the monsignor of Chilubula received a handwritten letter in poor English—the White Fathers were a French-speaking order, whose priests spoke Bemba well—which “made gross insults not to be repeated” and called the monsignor “a prince of demons, a serpent, and a sorcerer.” Apparently the work of an African Protestant, it demanded that the White Fathers return to Europe, where God would punish them. It was signed “your good roast mutton captivity, imprisonment, and bandages.” [19] Although it is difficult to surmise very much from the recipient’s summary of such a letter, the transformation of captured Africans into animals or, sometimes, cooked meat is a common feature of Central African vampire stories, and bandages figure prominently in vampire accusations in East and Central Africa.[20]