Jay Presson Allen: Writer by Default

Interview by Pat McGilligan

The "Jay" is actually Jacqueline. "Never particularly fond of her given name, she decided to use her first initial when writing (the more elaborate form. Jay, is the work of a Social Security Clerk, she says)," according to the Dictionary of Literary Biography.

Presson is her maiden name, mostly for byline purposes and long ago abandoned in routine introductions and everyday conversation. (More than once I have answered the phone and been surprised to hear her announce herself, "This is Jay Allen.")

Allen is the surname she took from her husband, the stage and screen producer Lewis Maitland Allen. For film, he has sponsored such unusual and rewarding fare as as The Balcony (1963), Lord of the Flies (1963), Farenheit 451 (1967), Fortune and Men's Eyes (1971), Never Cry Wolf (1983), and Swimming to Cambodia (1987); on Broadway, his eclectic résumé includes productions of Ballad of the Sad Café, Annie, I'm Not Rappaport,A Few Good Men, Tru, Vita & Virginia, and Master Class. The Allens have been married since 1955.

Born in San Angelo, Texas, she moved to New York in the mid-1940s with the goal of becoming an actress. She married, lived for a while in Los Angeles, wrote a first novel, Spring Riot, divorced. Moving back to New York, she realized she preferred a career on the other side of the footlights. Partly "by default," as she modestly puts it, because she was a good talker, devoted reader, and facile writer, Jay Presson Allen became a working scenarist, starting out in live television and graduating by degrees to Broadway, before being summoned to Hollywood by Alfred Hitchcock, in 1963, to toil on Marnie.

Since then, her career, divided between Broadway and Hollywood (mixing in a little television of the best sort), has been stellar. Any list of preeminent screenwriters who got started in the 1960s would have to include her. It helped that she usually worked with outstanding directors—Hitchcock, Cukor, Bob Fosse, Sidney Lumet. She earned Writers Guild nominations for Best Screenplay for her adaptation of The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie (based on her play), Travels with My Aunt (although in this interview she blithely discounts her contribution), and Prince of the City, for which she was also nominated for an Academy Award for Best Screenplay. She won the Writers Guild top adaptation award for Cabaret in 1971. She also won the Donatello Award (Italy's equivalent of the Oscar) for the screenplay of her novel Just Tell Me What You Want.

She is one of a handful of first-rank screenwriters of the post-1960s who also happens to be female. This has figured into her trademark of flamboyant female characters, stories that often focus on divorce and marriage or explosive relationships, family matters (including the pilot episode of the prestigious television series Family ), or occasional subjects with the interests of children at heart. But she hates being typed, can't be typed, and reminds you that she writes compelling male characters too; after all, she wrote and produced Prince of the City, one of the quintessential, New York true-life street stories about police and corruption, with nary a female character worth mentioning.

In general, her characters, male or female, are like herself—smart, tough, funny, slippery, resilient in life situations. I first met Jay Presson Allen several years ago when I talked to her about the director George Cukor for my biography of Cukor; and some of that material is incorporated into this interview. In that conversation, she surprised me by stating unequivocally that she had decided to quit writing motion pictures, that all the grief of coping with "development" and present-day studio procedures was not worth it. When I came back to see her some time later for Backstory 3, she had kept her vow, and therefore, all of her movie work since the mid-1980s has been invisible, rewriting scripts at the last minute for high pay and no credit. This is a lamentable trend among screenwriters of her generation.

She continues to write under her name for the stage. After years of independence from each other, she and her husband began to work together occasionally in recent years—he served as producer of her 1989, one-person hit play about Truman Capote, Tru, which she also directed.

Even though she is an easy talker, Jay Presson Allen does not enjoy giving extended interviews, and there are not many on the record. Like some of the other writers in Backstory 3, she wanted to polish her words before committing them to posterity. As part of our agreement, I let her read and hone the transcript. She took out nothing juicy. Her penciled touches, all in the direction of accuracy or crispness, only improved the text.

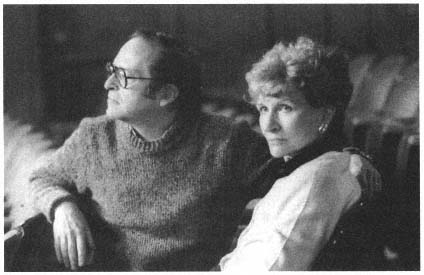

Jay Presson Allen in New York City, 1994.

(Photo by William B. Winburn.)

| ||||||||||||||

|

Television credits include contributions to Philco Playhouse, Playhouse 90, Hallmark Hall of Fame, The Borrowers (1973 telefilm, script), and Family (1976–1980, creator and story consultant).

Plays include The First Wife, The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, Forty Carats, The Big Love, and Tru.

Novels include Spring Riot and Just Tell Me What You Want.

Academy Award honors include Oscar nominations for Best Adapted Screenplays for Cabaret and Prince of the City.

Writers Guild honors include nominations for Best Script for The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, Travels with My Aunt, and Prince of the City; and the award for Best-Written Comedy Adapted from Another Medium for Cabaret.

I was surprised, reading a thumbnail sketch of your career, to be confronted by the information that you were born and raised in Texas. I had never paid that much attention to that interesting fact before.

Well, why should you?

Is there a Texas strain in your work?

Nothing—except maybe a kind of insouciance. I grew up in a little town called San Angelo, ranching country, later oil. A prosperous little town, not very far from the Mexican border. My father was a merchant, not very prosperous, coming out of the depression.

In those days there was still a kind of frontier mentality—a belief that you not only could do anything but that you had to. I don't mean literally, but it was certainly part of the psychological makeup of the people I knew. At the same time, I was an only child and was given a great deal of self-confidence by my parents—a lot of approval—and a lot of responsibility for an only child.

What was the nature of your education, growing up?

No education to speak of. Texas public schools and a couple of years in a place called, in those days, Miss Hockaday's School for Young Ladies.

Were your parents readers or writers?

Nah. Not at all.

What sort of interest did you have in theater and movies? Did you ever go to New York to see a play?

Oh no! (Laughs. ) We did go to Dallas to see whatever came on tour. The Metropolitan came every year, so I saw opera too. The Lunts toured every-

where, so we saw the Lunts in Dallas every two or three years. That was enormously exciting.

The movies were every Saturday and Sunday from one o'clock until somebody dragged you out at seven. That was literally how one's winter weekends were spent—in the moviehouse. Movies were very, very important. I remember seeing—I must have been eight to nine years old—one movie, and realizing how green other places were and how many trees there were elsewhere. I knew from that time that I would not be staying in Texas.

Did you travel as a child?

No. People from West Texas didn't travel. A wonderful friend of mine, Popsie Whittaker, one of the original editors of the New Yorker, went to Texas for the first time in his later years. This must have been in the 1950s. It was in the worst part of summer, and Dallas is a hellhole in the summer. He used to tell this story: He was being entertained by rich people, and sitting at a dinner table between two bejeweled women, he turned to one of these obviously rich, rich women, and said, "What I cannot understand about you people is that you could go anywhere to get out of this heat . . . why do you stay in Dallas?" And the woman said, "Well, Mr. Whittaker, it's hot all over Texas!" (Laughs. ) I only knew two people, growing up, who had ever been to Europe.

When did you first know you wanted to be a writer?

I don't think I ever wanted to be a writer. I became a writer by default. I was a show-off kid who got a lot of encouragement. I wanted to be an actress, from the earliest age, and I never presumed to be anything else. I came to New York at the first opportunity and discovered rather quickly that I only liked rehearsal. I discovered I didn't like to perform. It was a shock.

So I married the first grown man who asked me.[*] Then I lived in southern California during the Second World War, in a small academic town called Claremont. I had two friends who were in the movie business, but it never occurred to me to aspire to that world. It was exotic. It was not a business as far as I knew. My innocence was profound and sublime.

When I chose to leave that marriage, I felt guilty because my husband's big fault was marrying someone too young. I'd always read an enormous amount of trash, and I couldn't imagine not being able to write as well as a great deal of the stuff I was reading. I'd always written facilely, in school and letters. So I decided to write my way out of that marriage, and I did.

You mean you realized that writing would give you a necessary financial foothold? You consciously set about becoming a writer, so you could break free and become independent of your husband?

Yes.

* Allen declined to name her first husband.

What did you write?

I wrote a novel. It was published by a well-known house in '46 to '47. The name of it was Spring Riot.[*] Don't ask me what the title means. I haven't a clue.

Was it any good?

I certainly wouldn't think so! (Laughs. )

Was it hard to get published for the first time?

No. Easy. I was so ignorant—I thought if you wrote a book, it got published. It never occured to me that you could write a book which nobody would pay you for. The ignorance was breathtaking.

Was it a genre novel, coming-of-age? . . .

It was smart-ass: what I'd seen of Hollywood—and what I'd seen I didn't understand. There's nothing as dumb as a smart girl.

My agent was Marsha Powers, who had been Sinclair Lewis's teenage mistress, and whom he had set up in an agency. She was clever and active. I can't remember who sent me to her, but she took the book and sold it instantly.

What was the critical reaction?

Oh, I got mixed notices, which astonished me. I didn't really know much about notices. I was dumbfounded by all of it. Everything was a surprise.

Did it sell?

Some.

You didn't write another novel for thirty years. Did that experience temporarily quash your literary ambitions?

I don't believe I ever thought about literary ambitions. I just wanted to make some money and have some fun.

How did you progress?

I came back to New York, marginally divorced, and performed on radio and in cabaret. For my sins. Agony! It never occurred to me when I woke up most mornings, that some great grisly thing wouldn't happen—like my parents would be killed in an automobile accident—and that I wouldn't have to perform that night. Around four o'clock every day, it would become clear that I was going to perform. Then I'd go through the whole show, weeping. I hated it. But they wouldn't fire me.

You started writing again, little by little . . .

By that time, television existed, and once again, I didn't see how I couldn't do that well. My sights were never set very high. (Laughs. ) So I did—sold some stuff to television, Philco Playhouse, etcetera. About four shows, and they all sold to good programs. I knew I could make a living at it. I hoped I wouldn't have to.

Why? What did you hope would happen?

Something lovely—with chiffon and feathers.

* Spring Riot (New York: Rinehart, 1948).

Was the work of writing too hard?

No. But it wasn't wonderful. It always seemed like an exercise—like you were doing homework. Writing wasn't terrible, but you'd rather be out shopping, or playing tennis or poker, or something.

Did you feel you were falling short of what you were trying to do?

No. I don't think there was ever any question of setting my sights above what I was able to do facilely.

Don't you think there was something in your personality or character, in your personal circumstances, that helped make you a writer?

Well, I am a chronic reader. Compulsive, chronic reader. I could never get enough of books. I was and am a bookworm. And I've always been interested in the why of human behavior. I think most dramatic writers are natural psychologists.

What about inside of you—something that drew you, inevitably, to the act of writing?

Who knows? My God, that's an imponderable, isn't it? Do people ever know that?

Sometimes people have an inkling. Like: "I was a failure as an actress—an extrovert—therefore, I became a writer . . . "

I wasn't a failure. I could have been an actress. I obviously was going to be able to work. But the profession was alarming. I found the life so unsatisfactory so quickly that I backed off. Maybe I was frightened. I didn't think I was, but maybe I was.

Had you gotten as far as Broadway?

I was getting there. I did some road shows.

Then you wrote a play . . .

Then I wrote a play, which was optioned by producer Bob Whitehead. I was ambitious for that play. I think that was the first real ambition I ever experienced. I liked that play and was proud of it. I picked out this particular producer because he had produced Member of the Wedding, which I loved, and my play was also about a child. I thought he would like my play, so I sent it to his office. Ere long, I got it back, rejected, and was astonished.

I didn't send it anywhere else for a couple of months. Finally, I came to this conclusion; "I bet some reader rejected my play. I bet Mr. Whitehead never read it." So I sent it back. And I had guessed right. The reader who had read the play and rejected it had now gone off to Mexico with a beautiful actress. This time Bob read the play himself and instantly optioned it. The reader who had rejected my play came back in a couple of years, and I married him. (Laughs. ) That was Lewis Allen, my husband.

Was the play produced?

It was never produced. We had a very difficult time casting it. Mostly, the problem was with the child, but sometimes, it was with the lead actress. Bob was a fairly young producer, and he wouldn't go near anybody whose work he

didn't know. Among the people he didn't know—who I thought was absolutely wonderful, but she gave a bad reading, and he wouldn't even talk about her afterwards—was Geraldine Page. If we got an actress, he wouldn't go with the child; if we got a child, he wouldn't go with the actress.

Finally, Bob let it go, and I gave it to [producer] Fred Coe, whom I had worked for in television.&astric;It was optioned again—and again—but never done. By the time it would have been done, that kind of play—very small, very domestic—had become a television genre. It no longer had the size for Broadway. I lost that play.

How were you able to make a living while all this was going on?

One way or another. It wasn't so hard to make a living in those days. It didn't cost much to live. And don't forget unemployment insurnce. It was certainly important to me. I was young, I was healthy. If worst came to absolute worst, I could always take a real job. But I never did.

How long was it before you wrote your second play?

Well, I wrote Prime of Miss Jean Brodie when my daughter was . . . I think, six? She was born in '56—so about '63.

What had happened in the meantime?

I grew up a little. I got married and had a child and entered a very different world. When Lewis and I first got married, we both decided we wouldn't work anymore. Lewis had a pittance of income. We decided we would go to the country and live—he wanted to write, and I didn't want to do anything. So that's what we did. I had a baby and spent two and a half absolutely wonderful years in the country.

Lewis is a natural scholar. He's never had to be conventionally employed to be occupied. He is extremely creative . . . much more creative than I am. He always has extraordinary ideas for stories. He would do a wonderful draft, and then he wouldn't do the donkey's work. But he's gifted.

Anyway, one day Lewis came to me and said, "Let's go back to the city. I want to go back to work." So that was that.

What made you start writing again, specifically on Miss Brodie?

Because Bob Whitehead had become a good friend, and he was very encouraging. He pushed me: "Do a play, do a play, do a play." One day I picked up this little book [The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, by Muriel Spark (London: Macmillan, 1961)] and read it and thought it was wonderful. I could see a play, instantly, in that book. I called Bob and said I had found this book which I wanted to adapt into a play. He read it and said, "Do you really want to do this?" I said yes. He really did not think it would make a play. However,

* The producer-director Fred Coe is remembered warmly by several writers in Backstory 3. He produced more than five hundred television shows, including NBC's Philco-Goodyear Playhouse, the Mary Martin Peter Pan, and Playhouse 90 shows for CBS. On Broadway, he produced The Miracle Worker, and A Trip to Bountiful, A Thousand Clowns, and other noteworthy plays.

he was very generous, and insisted that I go to Scotland and do some research, which never would have occurred to me. I did; then I wrote the play.

That seems a great leap of faith.

When I wanted to do Brodie, nobody I spoke to about it thought it would make a play—except Lillian Hellman. Lillian said, "God, yes." But I always thought I was a very good judge of what worked in theater. We used to put a little bit of money into plays, here and there. I took a little flyer whenever there was something around I liked, with not much money. My batting average was very high, even before my husband.

You weren't deterred by people s skepticism?

You clearly want validation and approbation, but if you don't get it, it's not the end of the world. Nobody's writing it but you, so nobody can make the judgment but you.

During this period of time, leading up to Brodie, were you paying any attention to the possibilities of writing for movies?

No. It never entered my mind. I never heard of a screenwriter. That was the most esoteric thing I could imagine.

What is the first you heard of Hollywood or the first Hollywood heard of you?

People like [Alfred] Hitchcock have always had their finger in the agencies. Stuff is sent to them early. Preproduction. Hitch read Brodie, called me, and asked me to do Marnie.

"A very flawed movie": Tippi Hedren and Sean Connery in Alfred Hitchcock's Marnie .

You went out to Hollywood . . .

I don't think I would have gone if it had been anybody but him. I didn't know how to write a movie. I wasn't ambitious to do a movie. I certainly didn't want to spend any time in California. I had a child. I was going to have a play produced. There was every reason in the world not to go. I went out of curiosity as much as anything else.

Hitchcock guided you through the experience?

He was a great teacher. He did it naturally, easily, and unself-consciously. In that little bit of time that I worked for him, he taught me more about screenwriting than I learned in all the rest of my career. There was one scene in Marnie, for example, where this girl is forced into marriage with this guy. I only knew how to write absolutely linear scenes. So I wrote the wedding and the reception and leaving the reception and going to the boat and getting on the boat and the boat leaving . . . I mean, you know, I kept plodding, plodding, plodding. Hitch said, "Why don't we cut some of that out, Jay? Why don't we shoot the church and hear the bells ring and see them begin to leave the church. Then why don't we cut to a large vase of flowers, and there is a note pinned to the flowers that says, 'Congratulations.' And the water in the vase is sloshing, sloshing, sloshing."

Lovely shorthand. I often think of that. When I get verbose, I suddenly stop and say to myself, "The vase of water."

How literate was Hitchcock in terms of the script and his general education?

Hitch was certainly literate. He had no education but had read a lot. People like that are sponges and learn a lot from educated conversations.

What stopped him, then, from writing his own scripts?

I think a sense of being uneducated. He was very defensive about that. He was extremely defensive about class.

He was wonderful to me. So was his wife, Alma. She was very influential in everything Hitch did. She had been a successful editor before they were married, and she contributed a lot to his films. She was around a lot, though not for script sessions. But it was all very easy and open. Alma was knowledgeable, more sophisticated than Hitch. We were together all the time and got along well.

I should say they tried to teach me to write a script. I couldn't learn fast enough to make a first-rate movie, although Marnie did have some good scenes in it.

If you were getting along so wonderfully, what went wrong?

It is a very flawed movie, for which I have to take a lot of the responsibility—it was my first script. Hitch certainly didn't breathe on me. He loved the script I did, so that he did not make as good a movie as he should have made. I think one of the reasons that Hitch was fond of me and filmed a lot of the stuff I wrote was that I am frequently almost crippled by making everything rational. There always has to be a reason for everything. And he loved that.

Another reason is that Hitch was very concerned with characterization when he could get it, and basically, that's what I do.

That's scarcely what people think of when they think of Hitchcock . . .

I know, but that's what he loved. Maybe because his stuff was usually so plotty and convoluted, characterization escaped him more than he would have wished it to. He loved to talk about the characters. We talked endlessly. In fact, he wouldn't let me begin to write for almost two months. We just played and chatted, day after day after day. He got very involved in trying to get some reality in the relationship between the two people in the story, and he kind of got bogged down in that relationship. God knows, I did.

Maybe his interest in characterization was something relatively recent in his career—having something to do with growing older and maturing as a director.

Maybe. Hitch was enormously permissive with me. He fell in love with my endless linear scenes and shot them. In point of fact, he loved what I wrote, he shot what I wrote, and he shouldn't have.

People say he loved script sessions and the preproduction of a film, but that he hated the actual job of filming. I visited the set of his last production, The Family Plot, and it certainly appeared that he was bored.

I think he was totally bored during the filmmaking. He storyboarded every single, solitary thing. There was a drawing of every shot. By the time he got to the set, the work was done. He was no longer interested. He had done it all. What he responded to, the visual and creative work, was all finished in his head.

Was it at all odd or uncomfortable, in the 1960s being the rare female screenwriter in Hollywood?

No. I never knew the difference.

Did Hitchcock ever say anything to you—like, he had come to you because Marnie was a female character, and it was a female-oriented story?

Nope. Nope. Looking back in light of the sixties, women's lib, and all the historical things one reads, I know there were women writers at the beginning in Hollywood, but then there was a long period of time when there weren't any. Yet I never ever felt discriminated against. If anything, I felt that I waspromoted. Almost all of the men I worked with were supportive. If I was getting a bum rap somewhere, I didn't know it.

Why do you think it is that there were so few women screenwriters?

Well, there was that period after World War II and coming out of the fifties where women were supposed to be in the kitchen or doing their nails. There was a sense of psychological and even physical weakness about women—and therefore executives and directors maybe felt it would not be suitable to grind a woman writer down the way they would another man.

It's not a business for sensitive souls. I think the minute they figured you weren't going to cry, you were on track.

I had a very powerful man [in Hollywood] tell me shocking stories of criminal behavior, and I know it was because: one, the writer is a lowly thing, and two, a woman writer is a doubly lowly thing, perceived as being so unthreatening that they can say anything in front of you.

What was your impression of Hollywood this time around? Now that you were much closer to the business . . .

I still wasn't in the business. I was with Hitchcock, and he wasn't in the business either.

You were around soundstages, stars . . .

It didn't seem any different from what you'd expect. A star is a star is a star. They have stars in small towns, you know.

Well, does the Hollywood of today seem different from the Hollywood of those days?

Very. Very. Hollywood seemed leisured. Expected. Very organized. Everybody knew what was expected, and they pretty much did it. Now, it seems wild, frenetic. There's a lot of fear now, with good reason: everything costs too much. If some executive says yes to a movie, it's forty million dollars—bang. It's scary, and people are nervous. Scared.

Prime of Miss Jean Brodie really hit the jackpot.

I thoroughly expected it to . . .

Up to that time, however, your career had been relatively modest.

I never thought of myself as having a career. The term career was not all that applicable. I never set out to be a writer. I had no serious ambitions to continue as a writer. It's only in the last seven or eight years, as I've grown older, that I think of this as my career. Writing was just something I could do, with a little bit of talent and considerable skill.

What was the particular challenge of turning your play into a film?

When producers pay a great deal of money for a project, which they did for Brodie, they want what they buy. I thought the play could have been opened up an enormous amount. I was a little disappointed that we couldn't have made it richer. But they wanted what they bought, and the film was very successful. And it is a charming film.

Was there much involved in taking Cabaret from stage to screen?

Initially, I was approached by Cy Feuer, who was the producer, simply saying, "We do not want to do the book of the musical. We want to go back to [Christopher] Isherwood's book [Goodbye to Berlin (London: Hogarth Press, 1939)], and start all over again."

That seems a brave decision.

Onstage, Cabaret was a brilliant production with a wonderful score, but really the book was rather bland. The book of the musical didn't even suggest that he [the English tutor, Brian, played by Michael York in the film] was a

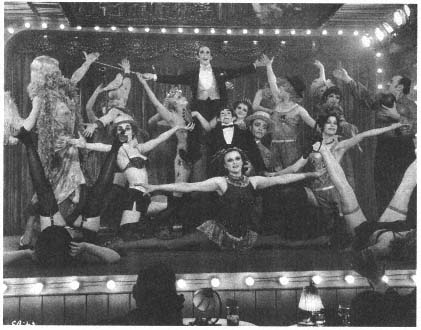

Joel Grey and chorus in the film Cabaret , directed by Bob Fosse.

homosexual, so in the end, the play made no sense. I had read Isherwood, of course, so I said I'd love to try.

Did you ever talk to Isherwood about it?

No. I never met him.

Of course, I had the benefit of starting out with that wonderful score, and I had the great joy of being able to work with [John] Kander and [Fred] Ebb on new stuff.&astric;We worked together on it, I thought and they thought, most happily.

What about [the director] Bob Fosse—was he around much?

He was around to a degree. During the actual writing, he was busy working on something else. I didn't find him the happiest collaborator I ever had. For a man who dealt with women as much as he was obliged to, let's say he had an extremely parochial view of women.

* Kander and Ebb are the composer-lyricist team best known for Cabaret and other Broadway musicals, as well as for the title track for Martin Scorsese's 1977 film New York, New York.

Did he hurt the principal female character? What was lost by his direction?

The film had less humor than the script. It's always very hard for me to see humor go down the drain. It's always an agonizing loss.

What did he bring on the plus side?

Oh, visual brilliance. He brought his enormous visual talent to the project. I just personally didn't like Bobby. We didn't like each other.

At a certain point, didn't you drop out of the writing?

I had another project to do. Then when they went to Germany and had to have some scenes, I suggested they take on a friend of mine, Hugh Wheeler.&astric;Was what Wheeler wrote congenial to your script?

Entirely congenial. The loss of humor was not Hugh, because Hugh was very humorous.

How did you get involved with Travels with My Aunt?

The inception of that particular project, I am almost certain, was Kate [Hepburn] wanting to give [the director] George [Cukor] a job. He was not getting work, he wanted to work, and there was no reason in the world why he shouldn't work. So he and Hepburn had teamed up with Bobby Fryer [who had produced Brodie as a film] to do Travels.

They called me, and I was involved in something else. I suggested Hugh Wheeler. To tell you the truth, I wasn't all that crazy about the material. The characters were wonderful, but I didn't really know how you were going to string all that into a movie. Bobby called me back several months later. They were unhappy with what Hugh had done. I agreed to take a shot at it.

I went and met George, and just adored him. I did a pretty straightforward, quite a competent script. At the beginning, George was very reasonable to deal with. We only locked horns on a couple of things. For one, George wanted to show Kate as a young woman in a flashback, but I thought it was a disservice to her and to the film. I believe in the film they show Maggie [Maggie Smith, who took over the role] as a young woman—which is more reasonable—but I desperately thought they shouldn't with Kate, and George was very, very determined to do that.

I don't think George was great with script. Storytelling was instinctive with Hitch. George was great with feeling and with the mood he wanted, but structurally, he didn't have Hitch's knack. However, George was a creature of the theater, and he was wonderful with actors. Hitch wasn't all that good with

* Hugh Wheeler wrote mystery novels under the names Patrick Quentin, Quentin Patrick, and Jonathan Stagge. The British-born playwright, novelist, and screenwriter contributed the books of the broadway musicals A Little Night Music, Candide, Pacific Overtures, and Sweeney Todd —all in collaboration with the composer Stephen Sondheim and the producer-director Harold Prince. Hugh Wheeler's screenplay credits include several adaptations of his mystery novels, Something for Everyone (directed by Harold Prince), and two co-scripts with Jay Presson Allen (Travels with My Aunt and Cabaret ).

actors, whereas George was wonderful with them. He was a cunning psychologist.

What happened between the cup and the lip is that Kate went into The Madwoman of Challiot [1969], and it was a kind of disaster for her. By the time I came out with my script, she didn't want to do Travels anymore. She didn't want to play another crazy old lady, not an unreasonable position. However, she would never admit it. She was loyal to George and reluctant to let him down.

George wanted desperately to work, and as she began to withdraw or find problems, he became frantic—like a boiling pot. He couldn't afford to deal with Kate, the real problem, because he would lose the project. He was genuinely devoted to Kate. They were bosom buddies; they laughed a lot and comforted one another. As we began to flounder, I think he panicked.

I rewrote and rewrote, trying to satisfy Kate, but I knew it was not going to work out. What she really wanted was to get the hell out of the project, and she was unable to face that. At some point, she had worked on parts of the script herself. I had once, a couple of years before all this, read a screenplay that she had written. It was pretty good. Now, I read what she was trying to do with Travels. It was talented and interesting, and I felt I had run my course; so I spoke to George, then to her: "Kate, you ought to write it yourself." So she did, and I went merrily on my way, happy to escape.

Kate wrote and wrote. My guess is that she was happy enough writing it, but she still didn't want to play it. Everybody was made very nervous. Jim Aubrey, who was running MGM at the time, had a very rough reputation, and he got a bellyful of all the toing and froing. So Aubrey called Kate up and said, in effect, "Miss Hepburn, report to work on script number fourteen on Monday morning." And she said exactly what he knew she would say, "Get yourself another girl." Of course, Bobby [Fryer, the producer] had Maggie Smith, who had done Brodie, standing by, and they were very compatible. So MGM gave George about thirty-seven dollars and sent him to Spain to make the movie.

Did any of it turn out to be your script?

The script they went with had one big speech of mine. Otherwise, it was all Kate's. It had nothing of Hugh's. One big speech of mine. I got a call from Bobby in the middle of the night from Spain, and he said, "We've run out of money, and we're only on page—something—what the hell do I do?" I said, "Just say, 'Cut.'" (Laughs. )

But when I saw the movie, I thought it was pretty darned good. George's work, considering the circumstances, was pretty darned good. It's a nice picture.

When credit time came up, I got a call from the Guild, asking me what I wished to claim. I said, "Oh, I didn't write anything in that movie. I don't want any credit. That is Miss Hepburn's script." The Guild's attitude was, in effect: So what? She's not a member of the Guild, no credit. Hugh was furious that I

Jay Presson Allen and director Sidney Lumet, her frequent collaborator in the 1970s.

wanted to take my credit off. Hugh was furious anyway. He wanted that credit. Bobby said he'd paid me a lot of money, and he wanted my credit on the picture. Everybody seemed mad at me, so I just shrugged and left my credit on. But I've never made any bones about writing that movie.

Kate got screwed on the credit. And did you see what she wrote in her book [Me: Stories of My Life, by Katharine Hepburn (New York: Knopf, 1991)]?[*] She got to the part about Travels with My Aunt and wrote, "It was not a very good script . . . " But she didn't ascribe the writing to herself! (Laughs. ) So I have taken the rap for it. That's all right. I did get paid a lot of money.

When and where did you meet Sidney Lumet?

New York is a small community, theatrically. I had met Sidney, on and off over the years, and we had once flirted briefly with doing a version of Pal Joey —not a musical version—with Al Pacino. I knew him to that extent.

All these years later, I had terrible trouble getting together a production of Just Tell Me What You Want. The studio had snapped up the book [Just Tell Me What You Want, by Jay Presson Allen (New York: Dutton, 1975)], but it hadn't got done

* Hepburn writes, "George Cukor wanted to quit as director because he felt that it was our property. I persuaded him that that would be senseless—that he should stay on as director. We might need the money. They had fired me because they felt I was holding up the project. That was true—I was holding it up because I thought the script could be improved. Actually, I was right—and the movie was not a success."

for a number of reasons. Finally, although I didn't think that Sidney was the ideal director for Just Tell Me What You Want, we took it to him. We didn't hear for months and months, a very long time; then one night, I got a telephone call from him. He had just read it and wanted to do it. That is how our partnership began.

How do Cukor and Hitchcock compare as directors in their approaches with someone more contemporary, like Sidney Lumet?

Sidney is a wonderful structuralist, great with structure. Sidney has his most difficult time with humorous dialogue. It's not that he doesn't get it—he does; he has got a lovely sense of humor. But he hasn't found a way to shoot humorous dialogue as brilliantly as he shoots everything else. Like dramatic scenes—Sidney goes after drama and gets it by the throat.

That must not always be to your advantage, since one of your strengths is smart-ass comedy.

It is possible that someone else would have served that script better, but I think he served it wonderfully. We lost some humor in Just Tell Me What You Want and also in Deathtrap. Just Tell Me What You Want was partly a terrible circumstance—we lost the voice-over of Myrna Loy. Her voice turned out to be weak, shaky. Instead of letting me restructure the piece—Sidney is always in such a hurry—he gave the voice-over to the girl, and it was wrong.

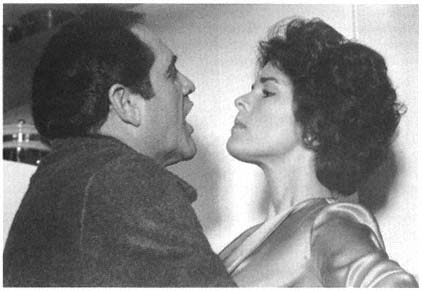

Ali MacGraw and Alan King in Just Tell Me What You Want .

We lost the very first scene, a key scene, at the beginning of Deathtrap, because an actress didn't pan out, and Sidney wouldn't shoot it over with somebody else. He just cut it. Sidney's abiding sin is speed, which I empathize with. We're speeders, both of us. We like to go fast. The speed is thrilling. It's wonderful to work with someone that sure. I adored working with Sidney, and one of the things I loved was his speed. But you pay a little price for it.

Do you have other things in common—do you start to think alike—when you are working together?

With casting, for example, we are always so close together, just on the nose. I went into my first meeting with Sidney for Just Tell Me What You Want with a secret agenda, which was Alan King to play Max—but extremely diffident about the suggestion. We talked for a couple of hours, at which point Sidney said, "I've got an off-the-wall suggestion for Max." I said, "Who is that?" He said, "Alan King?" We just fell on each other.

We cast Prince of the City, all the many parts—a very large cast—hardly discussing the casting. One of us would say a name, and the other would say yes. It was like that throughout our work—all three movies.

Do you have a favorite film, among those you did with Sidney?

Of all my work, Prince of the City is my absolute all-time favorite. I like scenes from everything else. That's the only one that I like in totality.

How did that project get started—with you as producer?

The book [Prince of the City, by Robert Daley (New York: Dutton, 1975)] was reviewed very late in the game. I read the review, and went and bought the book. I thought, "Oh yeah. This is Lumet!" Instantly, I called the publisher to see who the agent was, but the book had already been sold. It had been sold to Orion for David Rabe as screenwriter and Brian De Palma as director. I didn't think that two men who leave their prints so richly on material would be able to do this book, because there wasn't any room for the screenwriter and not all that much room for the director. The material just dictated what was to be there.

I didn't think they would ever come out with the film, so I called John Calley at Warner Brothers—at that time Warner Brothers umbrellaed Orion—and said, "If this falls through, I would like to get this for Sidney, and I want to produce it, not write it." He said, "If it falls through, it's yours." At that point, I showed the book to Sidney, and he just flipped. We had to wait to see what would happen. Well, we waited and waited and waited, and it seemed as if nothing would come of it. And Sidney was within twenty-four hours of signing up for another movie when we got the call.

But I didn't want to write that movie. I was tired. I just wanted to produce it. I thought it seemed like a hair-raising job to find a line, get a skeleton out of the book, which went back and forth . . . all over the place. I thought it was too big a job. I told Sidney there were other writers we could get. But Sidney said he wouldn't do it if I didn't write it. He said, "Would you write it if I do

an outline first?" I said, "Do the outline, and we'll see." So we sat down together and went over the book and the scenes, and agreed on the scenes and characters that we felt we absolutely had to have, as well as a general thrust for the movie.

We were sharing an office, and he would come in every day with a legal pad, and sit at his desk: scribble, scribble, scribble, Mr. Gibbons. I was horrified because I knew he had to be writing scenes. I thought, "Well, this is the end of a beautiful friendship, because he's going to turn this stuff in, I'm going to read it, and I'm going to be forced to reject it." Anyway, two or three weeks pass, and he hands the pages to me. If memory serves, something in the neighborhood of one-hundred handwritten pages. My heart really, really sank. I went home and read the pages, and he had written scenes, and most of them were not right. But the outline was just wonderful. I went back to him and said exactly that. Then I took what he had done, and went to work.

It was the first time I had ever written anything about living people—so I interviewed almost everybody in the book. And I had right next to me—the minute I was stuck on anything—all those phone numbers to dial. I could dial the real characters and say, "This doesn't sound right to me . . . " Mr. Daley,

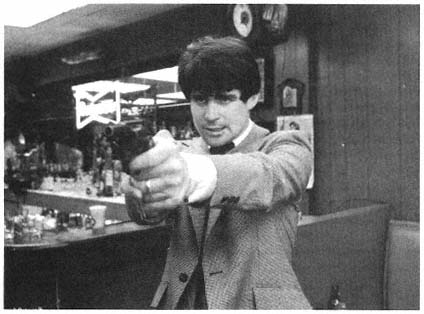

"My absolute all-time favorite": Treat Williams in Prince of the City .

a good Catholic boy, was more a believer than I was. Eventually, I sat down with my interviews, what Sidney had done, the book and the telephone numbers, and turned out a three-hundred-and-some-page script in ten days.

The studio was so generous. A three-hour movie is very, very hard to sell. But we didn't know any other way to do the movie. We said, going in, "We're going to have a three-hour movie. Do you want to do it—if we can make it for ten million dollars?" They let us do it.

Afterwards, you continued to function as your own producer. Why?

It seemed easier than the alternative, dealing with someone new to the projects, somebody else to argue with. Producing is not a job I normally seek. With Sidney, it was easy. Sidney and John Calley made it easy.

You and Sidney seem to have been very fortunate, in general, at Warner Brothers.

Sidney and I never had any trouble. We were always under Calley's wing. John was the head of production at Warner Brothers. He is bloody smart and so funny. And a facilitator. Unlike most studio executives, he personally knows how to produce. He makes your job easy. He's still a very good friend.

It was Calley who gave you and Sidney the green light to do so many films?

Yes, he did, and he would have given me a green light to do more—I think I disappointed him. I have just never been very ambitious.

Why did the partnership between you and Sidney end?

Everything ends. Sidney wanted very much to work with David Mamet, which was right for him, exactly what he should have done. John quit, not long after that. He stopped having fun. And by that time I was exhausted.

How detailed are your scripts?

Very. Maybe overdetailed. I overwrite, so most of my scripts need a lot of cutting. I've been lucky in that I've been in on the cutting of almost all of them. Which I like to do—I've had directors order me to stop cutting.

Do you write much description?

I loathe writing description, but I do a lot of it.

Camera direction?

Oh, good heavens, no. No director wants to be told where to put the camera, unless it's specific to a line of dialogue. I don't dictate to a director. I work for a director. If you don't work very closely with a director, you're not going to see anything you want up on the screen. There's no way. So you had better invite the gentleman to piss a little on the script. Put his mark on it. Make it his.

To what percentage?

To the percentage that is necessary.

What percentage is unacceptable?

I don't have that option, do I?

You have the option of quitting or taking your name off the script.

They don't care if you quit! (Laughs. ) I've worked with a couple of directors I wouldn't work with again for absolutely personal reasons. One

of them had no humor, and that's death for me. Another one was a kind of depressive, and working to get him up to a state where he could contribute took all of my energy. I was in those situations before I could get out. Once in, I saw them through. But those two people I would never want to work with again. Otherwise, I've had very good experiences with directors.

Do you put in any blocking suggestions?

Not much, unless it's necessary physical business.

Do you contribute either in the script or discussions to visual ideas in the film?

Sometimes. I think something turned out wonderfully in Cabaret that was mine, which was when the camera pulls back, from a young boy singing solo to show the chorus of Nazi voices rising around him. That was mine. I suggest something every now and then. It's not something that I normally want to do, because that really is the director's job, and I don't have a great talent for that. If I wanted to do that, I'd try to be a director.

What are the hardest elements of the story for you?

For me? Plot.

The easiest?

Dialogue. Because I'm naturally articulate. Also, I think because of that little bit of theater training I had, all those years of wanting to be an actress, when I was a child and when I was in plays. I did virtually nothing else from the time I was about fourteen.

Do you feel you have a particular strength with female characters?

Yes, but I also think I have a particular strength with male characters. I've written a lot of good male characters. Male characters are easier to write. They're simpler. I think women are generally more psychologically complicated. You have to put a little more effort into writing a woman.

Therefore, women are twice as hard for men to write?

I'll say. Men keep writing themselves. Or else they write fantasies of women.

Do you feel that in your career you have tended at all to specialize in writing female characters, either by chance or otherwise?

I am attracted to a piece if it's exciting, theatrically exciting. Or if it has a marvelous character. I specialize in writing characters that interest me. I don't care whether the character is a man or a woman. I couldn't care less.

Yet quite often they turn out to be women . . .

They send me that stuff. I seldom go after anything. I never go after assignments. I almost never initiate anything. That's not quite true—I did initiate Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, Just Tell Me What You Want, and Prince of the City. But that's about it.

It occurs to me that you are also attracted frequently to stories involving parent-child relationships, or children—child characters.

I love writing children.

Why?

Because they're fun. It's almost impossible to write a dull kid.

Does your interest in writing children have anything to do with being a woman or a mother?

You bet.

The Borrowers is one I wish they'd put out on video—for my children to see.

I myself never saw it. I had totally forgotten The Borrowers until you mentioned it just now. I was out of that project at an early stage. I would love to see it.[*]

Writing children?—that's an only-child syndrome. I'm an only child, I have an only child. Only children think a lot about their childhood, and it maintains interest. In any case, I find itty-bitty babies the most riveting things on earth. They are little learning machines, and there's a kind of violence in their madness to take everything in. Children are fascinating. It's exciting to be around them. Exhausting but exciting.

Tell me a little bit about your writing regimen.

I don't do anything but write.

All day?

I get up and I write and I write, until I have to go to sleep; then, I get up, eat something, then go back to work. I do a script very fast, because I don't stop. All day. All night, until I'm too sleepy.

As a result, you can do a script in ten days?

Sure I can. So could you—if you wrote eighteen hours a day. Of course, I do a lot of rewriting. A tremendous amount of rewriting.

Do you drink coffee, smoke cigarettes while you are writing?

No. I don't have any vices. (Laughs. ) I take a little exercise now and then, a little run. I use an old Underwood 1949 typewriter, which takes a lot of pounding and gets a lot of aerobic stuff going for you.

Do you invite or suffer any distractions—phone calls from friends, dinner parties?

If I have any distractions, the game's up.

What's the hardest part for you?

Getting started. Making up my mind to do it. In effect, it's a sink full of dirty dishes. You know you're going to be sitting at a typewriter for eighteen hours a day for however as long as it takes. That's not an enthralling prospect.

What's the easiest part?

The easiest part is going into some kind of overture. When you come out, you don't know who wrote it. That's kind of wonderful. You start writing at eight

* Based on Mary Norton's children's classic The Borrowers, first published by Harcourt, Brace in 1953, this film is about a miniature family living underneath the floorboards of a Victorian house. Since this interview was conducted. The Borrowers has become available on videocassette.

o'clock in the morning. The first thing you know it's two, and you don't remember that time. That's when all the good stuff happens. If I have to labor and sweat, it's never any good.

Reluctantly, I went back and read Just Tell Me What You Want recently—I hadn't read it since I wrote the screenplay. It was much better than I had thought it was. It's really funny. The good parts of it I have no recollection at all of having written. The doppelgänger effect. Wherever it went inert, that part I remember.

Do you ever experience writer's block?

I got writer's block one time and never again. It's a funny story, do you want to hear it? After I got Bob Whitehead to buy Brodie and he sent me to Scotland, I came home and I never looked at the book or thought about it again, for almost a year. The option was almost up. I didn't do any work. I wasn't worried—I didn't even know I had writer's block. I just thought I wasn't ready to do it. As I am a great procrastinator, this didn't alarm me. Finally, with not much time left, I had to sit down and say to myself, "My God, I'm not going to write this thing." My shame was profound.

I had a friend—Bill Gibson's wife, Margaret Brenman Gibson, who is a therapeutic hypnotist, an analyst[*]—who once gave me some book to read on hypnosis. I decided I would be a marvelous subject—I'm so suggestible. So I went to my doctor in New York and told him I wanted to try hypnotism. My doctor said the best guy on the East Coast was here in New York, and was doing a paper on writer's block. His name was Lewis Wolberg.

So I made an appointment with Dr. Wolberg. Now, I'm always on time—I'm not early or late; it's an inner clock, I don't even have to check my watch—but I got to this appointment about forty minutes early. I had to question that. What I was doing was checking out the pictures on the wall, the magazines, the decor of his office, and finding everything lacking. It was such a comical psychological ploy—trying to put down the doctor before I saw him, while at the same time I really did think I wanted to be helped. So I went in.

Dr. Wolberg was a very unthreatening man. He was very, very smart and I liked him instantly. I told him, "Listen, I think I would be a good subject. I have this problem . . . I come to you with an open mind, but at the same time, this is what I did while I was in your waiting room . . ." He laughed. Then he gave me some tests and asked me what kind of problem, specifically, I was having and what I thought was causing it. I had a fairly good idea and told him. "Well," he said, "that is a highly sophisticated idea of what the problem might be, and you might be right . . ."

What was the specific problem?

* Margaret Brenman-Gibson is also the author of Clifford Odets, American Playwright: The Years from 1906 to 1940 (New York: Atheneum, 1981).

I don't want to tell you. (Laughs. ) He said, "Why don't we do several sessions? Meanwhile, I will teach you to hypnotize yourself, and you can do it at least twice a day at home. I think you're going to be a breeze." He also warned me, "Don't expect a deep trance, because it's not necessary. You'll hear traffic and noise, etcetera . . . "

He told me the name of the trance that he was going to put me into—which was hilarious. He was going to put me into what they called a hypnagogic reverie. So I submitted myself to a hypnagogic reverie. It was very relaxing. Though clearly I wasn't hypnotized, I kind of felt sorry for Dr. Wolberg because he seemed so sure of himself, and I liked him. But the trance obviously wasn't working. So when he told me to raise my hand, I raised my hand—like in the movies. Then he said he was going to count to twenty, and after that time, he wanted me to fantasize for about twenty minutes. I should have known what was happening, because what I had wasn't a fantasy; it was more like a dream.

I was in Mexico in a cathedral where the walls were all covered with beaten gold. Down at the altar, there was a bishop wearing a bishop's miter with a face very like Dr. Wolberg's. I went down to take the wine and the host—mind you, I am not only not a Catholic, I am a stone atheist. I knelt down, and when the bishop with Dr. Wolberg's face came to me with the wine, I spit it out and said, "Don't guess! Bless!" I got up and went to the wall and rolled down a big sheet of gold and hugged it to me. It was very lightweight. I carried the gold outside, sat on the steps in the sunshine, watched the peasants go by, and was very happy. I had to laugh at the dream. Any fool could figure it out. It was so obvious: Help me if you can, but I prefer to help myself.

Afterwards, I told Dr. Wolberg I hadn't been hypnotized. He said, "Oh, it was as good as . . . don't worry about it. Next time it'll work better . . . trust me." Then I walked home. His office was on the upper East Side, and I found myself standing on the corner on Eighty-sixth and Lexington, waiting for the light to change. I became aware of a woman standing next to me, staring very rudely at me. I whipped my head around in a confrontational manner, then suddenly realized I was singing, quite loudly, "I'll Get by, As Long As I Have You!" I went home and called my husband and said, "I think I was hypnotized."

In any event, I did begin to do the exercises at home while continuing to see Dr. Wolberg. He kept insisting I was dreaming about the book, but I never dreamed about the book. I didn't even open the book. I didn't do a speck of work, though I was having obvious success with the hypnosis. So much so that one day Dr. Wolberg said to me, "You're doing so well, is there anything else you'd like to work on?" I said, "Yes, I don't go out very much, I'm not very gregarious, and I think my husband suffers from this. I would like to go out more spontaneously than I do." He said, "Well, we can do that."

A couple of weeks later, my husband was getting ready to go out. By this time, I was getting quite good at hypnotizing myself, and I said, "Where are

you going?" He said, "I promised two guys downtown I'd take a look at their film." Lewis had, by that time, produced The Connection [1961] and The Balcony [1963], and he attracted avant-garde and amateur filmmakers. I said, "Well, I'll go with you." He said, "You're not going to enjoy it." I said, "Sure, I will. I'll go." I got up and got dressed and said, "See, it's working!"

One of the two guys was a poet, the other a filmmaker; and they showed us this appalling film, very sixties stuff, about a naked, three hundred pound woman. I thought to myself, This is a good time for one of my exercises, and I put myself out. The first thing I remember hearing was the film winding down. I came out, smiling and cheerful. Then I realized they were loading up the machine again. I asked one of the guys if they were going to show another film. He said, "Yeah." I said, "Gee, I really hated that one. Is there any place I can go and read?" The guy was cool. "Sure," he said, "go into the library. There's plenty to read." So I went into the library, and there were about twenty-five hundred volumes of poetry. I have no poetry in my soul. But I cheerfully picked up a book and started to read.

After a while, I began to hear some quite alarming sounds from the other room—dozens of people talking and partying. They had really set Lewis up, sandbagged him, invited everybody they knew to come down and see the film. At that point, the star of the first movie came into the library. She was very rowdy. I thought, "Well, I'll journey on." I went up to Lewis and said, "Do you think I could go home?" He said, "Nobody's going to notice if you go . . . " As I sidled up to the door, a heavy hand hit me on the shoulder. This enormous, fat woman accosted me. She said, "What's the matter, aren't we good enough for you?" I said, "Actually, no . . . " I understood how horribly rude I had been, that I had disgraced my husband, and yet I was euphoric, very high.

The next day, I went to see Dr. Wolberg and told him what had happened. He said "My God, what suggestion did you give yourself when you put yourself under?" I said, "I told myself that I would find some way to enjoy the evening." He said, "Jay, that doesn't even begin to be specific enough!" (Laughs. )

In any event, after my sessions with Dr. Wolberg concluded, a friend of mine loaned me his house up the Hudson, and Lewis drove me up. I always have to be by myself to write, and I didn't have a studio in New York at that time. I knew I couldn't write the play. There was no question of writing the play. Not only had I not dreamed about it, I hadn't even thought about it, marked the book, nothing. I thought, "Well, I will sit at the typewriter eight hours a day for the three weeks I have left, and I will be able to tell Bob that I tried."

I went into this house, and before I went to bed that night, I went through my hypnotic exercises again because, apart from everything else, I had been to the dentist recently, and on that level, the hypnosis was wonderful. The next morning I went through my little drill again, then sat down at the typewriter and wrote the only thing I knew to write—which was "Act 1, Scene 1." I came

to eighteen hours later with the play over a third written. I finished writing it in three days. And what I wrote was 95 percent of what went on the stage. It was like pulling the plug out of a tub. I knew I would never, ever experience writer's block again.

I'm struck by how flexible you seem in your approach and the broad range of interests evidenced by the disparate subjects of your scripts.

I may not be the best writer in Hollywood, but I think I have the greatest stretch. I can write about more different things than anybody else I can think of.

You can say that definitively?

I say that without a pinch of modesty.

Does the price tag, or how much somebody invests in your work, affect your attitude towards the work?

Oh yes. Absolutely. You feel terribly guilty if you don't deliver. I took a job, a few years ago, the first time I ever took a job where I was worried about not liking the material enough. It was a very big book, and there was some wonderful stuff in it, certainly enough to make a movie. But there was a world of garbage in it too, and I knew the producers were going to want a lot of that left in. I really shouldn't have taken the job. Somebody told me they overheard one of the producers saying, "Be careful . . . I think she's taken an assignment. " It was the first time I had ever heard that expression, and it absolutely shocked me. Because I can't imagine anything as dreadful as to have to work on something for which you have no sympathy, no feeling.

Now there may have been people who did movies and TV in the past who really did hack work and never tried to rise above it, but I've never known any of them. I always try to do my best. (Laughs. ) And the more it pays, the harder I try. I like to earn my money. At the same time, I don't know anybody who doesn't write except the best they can, almost always—the best they know how to write—no matter what they are paid.

When I talked to you a couple of years ago, you shocked me by saying you thought you weren't going to write a movie from beginning to end ever again.

It really stopped being fun. Movies cost too much. When an executive green-lights a project, he may be risking his own job. So something has been thrown up to protect the executives from the talent. The talent is, almost by definition, persuasive. Consequently, dangerous. The barrier that has been thrown up is called Development. So today, most scripts are developed: which means "writing by committee." No fun. But there's an upside: "developed" scripts tend to need rewrites—from outside the "development circle." A production rewrite means that the project is in production. Big money elements—directors, actors—are pay or play. There is a shooting date. The shit is in the fan.

And that's where writers like me come in. Writers who are fast and reliable. We are nicely paid to do these production rewrites . . . and we love these jobs.

Without credit?

Never with credit. If you go for credit on somebody else's work, you have to completely dismantle the structure. Who wants a job where you have to completely dismantle the structure? I only take things that I think are in reasonable shape. The director and the producer and the studio may not necessarily agree with me, but I think the script is in reasonable shape. Besides, no one but the writer ever knows how much trouble any one piece of work will be. Only the writer knows that. Only the writer. So I take what looks to me like something that is in good enough shape, yet which I can contribute to and make it worth the pay they are going to give me.

Do you ever talk to the original scriptwriter?

No. Well, once. I was once asked to do something on a David Mamet script. Not an original. An adaptation. I thought his script was great. The woman character was weak but easily corrected. It was called The Verdict. I told the producers—David Brown and Dick Zanuck, who had produced Brodie —the script was wonderful. They said, "Yes, but we want certain things from the book he's written out, and he doesn't want to go on with it." So I called David Mamet and said, "Do you really not want to go on with it?" He agreed that was the case. I said, "Then I'm going to take the job." He said, "Be my guest."

I did a draft and did make the woman strong, and the producers were thrilled with it. I said, "Get Paul Newman for the lead and get Robert Redford to direct, and you'll have both of their names up there." Before anything could happen, Bob Redford came to look at our house in Connecticut at a time when we thought we were maybe moving. He saw a copy of the script in the house. He said, "I've heard about that script. Is it for me?" I said, "No, you're too young." He said, "What do you mean, I'm too young?" I said, "You're still radiant, Bob. This guy's really beat up." He asked, "Can I read it?" I said, "Sure, but I'll have to tell David and Dick that you've got it." He said, "No problem," and took it away. The next thing I hear, he's signed to act in it.

For one year, he jerked them around. Redford has a pattern of finding something that he thinks is well written and trying to make it fit for him. He did that with another script of mine, the only script I ever wrote from scratch that was never produced, a western. In any event, he drove Dick and David crazy. Finally, they did a very bold thing: they fired Redford. This was at the peak of his career. Then they hired [Paul] Newman, provided they could get a director.

David [Brown] called me and said, "Do you think Sidney would direct this movie?" I said, "I think he would love this movie." He said, "Will you ask him?" I said, "Sure." I went into his office—we were still partners—and said, "There is a script called The Verdict that I have been working on . . ." He said, "I know that script. That's David Mamet's script . . . I read that script once." I said, "Well, he did the first draft, and I have done the second draft, and David

and Dick want to know if you will direct it." He said, "Yes! I want to direct David Mamet's script!" I said, "Dump my script?" He said, "Jay, do you want to do a rewrite on what you've already done, just to please me? Do you want to go through all that?" I said, "No." He said, "You've got all the money, haven't you? All you're going to get?" I said, "Yes." He said, "Then, what do you care if I do David Mamet's script?" I said, "I don't." (Laughs. )

You didn't?

I didn't. Mamet's script won an Academy Award. But the woman character went back to being weak! (Laughs. )

Aren't people amazed that someone like yourself, with all of your background and career, is willing to do this kind of discreet work?

There are more than one of us out there. These jobs are quick, sometimes they're even fun, and you don't have to take the terrible meetings. They're not breathing on you. They're just desperate to get a script. I've never taken anything that I knew I couldn't help. They pay good money. I need the money. We've built a house in Italy, and you can't imagine how soft the dollar was during construction.

You're willing to do production rewrites because the alternative is so harrowing—seeing a movie through from beginning to end?

Oh, I don't think I would ever want to do that again.

That's definite—you won't do another movie of your own?

Never say never, but that's generally more work than I want to do now. I'm tired of a certain kind of writing. I'm tired of the terrible responsibility of a script from scratch and of the terrible price it costs to make the movies today, so that nobody is having much fun. I used always to have myself joined at the hip of a director who could protect me. That's not going on as much now as it was. It's not as easy a job as it used to be, just on the level of the word Development. I just don't want to do it.

That's so mysterious to me.

Listen, it's more complicated now. Less amusing. I'm ancient, and there are other things I'd rather do.[*]

* At this writing, Jay Presson Allen's play Breaking and Entering is scheduled to creep into Broadway sometime during the 1996–1997 season.