PART SIX—

HISTORICAL REVISIONS

The five articles and one interview in this section have to do with historical revisions in quite different senses. The Hans Barkhausen and Gösta Werner pieces employ archival research to cast doubt on claims made by two filmmakers concerning their roles in history. Barkhausen's short article on Leni Riefenstahl was based on extensive research that he did in the then newly available "voluminous documentary material of the former Ministry of Propaganda and Public Enlightenment [headed by Joseph Goebbels] and . . . the former Reich Ministry of Finances." The evidence that he found overwhelmingly refuted, and exposed as a lie, Riefenstahl's longtime claim that, although her earlier film Triumph of the Will (1936) had been commissioned by the Nazi Party, Olympia (1938) was financed by her own company with no support by the Third Reich. When the same Goebbels earlier offered Fritz Lang the directorship of the film industry for the Third Reich, Lang left Berlin for Paris that night—he didn't even have time to withdraw his money from the bank. This Lang anecdote—it's the one to tell if you're telling only one—has been passed on by several generations of film teachers and film textbooks. Doing some archive work of his own, as well as consulting secondary sources, Swedish scholar Werner has come up with a more complex story.

Lincoln Perry, who took his stage name, Stepin Fetchit, from a racehorse, may well have been the most important black performer in the first forty years of American film history and was, up to that time, by far the most successful, critically and financially. Among the high points of his career were two films he made with Will Rogers: Judge Priest (1934), also featuring Hattie McDaniel, and Steamboat Round the Bend (1935), both directed by John Ford. As early as 1946, black groups objected specifically to the Stepin Fetchit screen persona, which they regarded as degrading to blacks. Hence he made only one other film—Ford's The Sun Shines Bright (1953). In an interview with Joseph McBride in 1971, Perry argued persuasively that in the course of his

event-crowded life, he had broken barrier after barrier not only for black film actors, but also for black people generally. This view was confirmed when Perry was among the first group of inductees into the Black Filmmakers Hall of Fame in 1974.

The Beverle Houston, Leonard J. Leff, and David Ehrenstein articles pursue historical revisions in the realm of the criticism of films and filmmakers. Houston develops an alternative approach to and interpretation of the films of Orson Welles. Leff examines less the narrative events and visual perspectives of Citizen Kane than a number of interpretations of that film. Ehrenstein's essay on Desert Fury most certainly rereads a forgotten film and thereby restores it to public discourse, but this is only the beginning.

In her influential study of Welles, Houston notes that Charles Foster Kane is forced to leave his family too early, but that George Minafer in The Magnificent Ambersons (1942) leaves his family too late. At the center of these two films and a third—The Stranger (1946)—are family-centered narratives that focus on what Houston calls the Power Baby,

the eating, sucking, foetus-like creature who, as the lawyer at the center of The Trial [1963], can be found baby-faced, lying swaddled in his bed and tended by his nurse; who in Touch of Evil [1958] sucks candy and cigars in a face smoothed into featurelessness by fat as he redefines murder and justice according to desire; . . . and who, to my great delight, is figured forth explicitly in Macbeth [1948] where, in a Wellesian addition to Shakespeare, the weird sisters at the beginning of the film reach into the cauldron, scoop out a handful of their primordial woman's muck, shape it into a baby, and crown it with the pointy golden crown of fairy tales.

Returning to the moment of Mrs. Kane's decision to send her son away—and her blaming it on her husband—Houston notes the son's running to his father until his mother stops his progress with a sharp "Charles!" She speaks of the camera's dwelling on the mother's enigmatic look at this moment as "one of the film's most powerful and puzzling images." Of the scene generally, she concludes that we "must accept the overdetermination [i.e., undecidability] of this genuinely ambiguous moment." When Isabel Amberson marries dull Wilbur Minafer rather than dashing, amusing Eugene Morgan, she lavishes her love on young George, creating for him a "state of uncontested love with the mother, secure inside a warm, dark house. . . . No reason to get a job or a profession. No reason ever to leave this nest of complete dependence and desire." When George finally ventures forth, a car hits him and both his legs are broken. This

reminds us of Kane's final years in a wheelchair and prefigures maimed legs in other Welles films: Arthur Bannister's limp and double canes in Lady from Shanghai (1948), Mr. Clay's immobility in The Immortal Story (1968), and the bullet in the leg that Hank Quinlan took for Pete in Touch of Evil —Hank later leaves his cane at the hotel where he murders Joe Grande.

Houston's discussion of women in Welles's films develops striking new perspectives. After she leaves Kane, "Susan's real return has been to her position within another social class." Lucy Morgan in Ambersons is forced into a more regressive return: life with her father, and celibacy. Especially interesting is Houston's account of The Stranger : Mary Longstreet has married a man who turns out to be a Nazi; how could a nice girl have make this bizarre choice? Nazi hunter Wilson wants Mary to be shown the kind of man she married, and he is willing to put her in danger, by using her as bait, to accomplish this. Her father and her brother agree and keep her under surveillance. This makes the control of the woman complete: "The dangers of active female sexuality and choice-making take on the resonance of a national and cultural disaster." The husband dies and deserves to do so "at the rational plot level," but the point is that "the aroused woman, the sign of difference as danger," is subject to "a struggle to force her into passivity and return, and often a lethal one."

Despite what the title "Reading Kane " might suggest, Leonard J. Leff does not provide yet another interpretation of Citizen Kane . On the contrary, his purpose is to question the assumptions and practices that scholars and critics have pursued for decades. In this bracing enterprise, he draws upon reader-response criticism, particularly the work of Stanley Fish, including his call to "slow down the reading experience so that 'events' one does not notice in normal time, but which do occur, are brought before our analytical attentions." Leff looks especially at Kane 's narrators—Thatcher, Bernstein, Leland, Susan, and Raymond—in order to see if other commentators, such as Bruce Kawin in Mindscreen , are correct in treating the sections of the film associated with each as a unified presentation of that character's perception. Leff argues that the Thatcher section does not remain within the banker's mindscreen, but deviates frequently and rapidly—sometimes within a time span of sixty seconds—to the mindscreens of others—now Mrs. Kane, now Charles, now a "supra-narrator." Reviewing various critical theories as to why Mrs. Kane sends her son away, Leff concludes, "These and other interpretations, though not unreasonable, miss the point. At this moment, the text has slipped out of our control: we may not say with any certainty why Mrs. Kane sends away her son."

"Desert Fury , Mon Amour": David Ehrenstein is the author of the article that bears this title, but the remarkable voice that we hear in it is a creation of the text itself. "A Film of No Importance : In the end it all comes down to Desert

Fury. Desert Fury ? You haven't heard of it? Of course you haven't. Why should you? . . . [T]his turgid melodrama . . . figures in no known pantheon or cult. Its director, Lewis Allen, is devoid of auteur status. [Desert Fury: ] Not good. Not bad. Mediocre. In fact, one might even go so far as to call it quintessentially mediocre."

The voice of the text is often furious, or Fury ous. Furious at theoretical critics whose bad faith deflects the auteur status of the films they choose to analyze. Furious that it is devoting so much time and attention to this resplendently blah film; but furious also at pretentious art films that critics still claim to admire, such as Hiroshima, Mon Amour , a film that, for all its merits, is devoid of humor. And while we're on the subject, humor is something in which this reading abounds: dry wit, belly laughs, and more than the seven types of irony that William Empson distinguished. All that said, the text's voice is genuinely interested in Desert Fury , at least fitfully—the strange plot, Lizabeth Scott's displacements of affect from straight Tom (Lancaster) to the dangerous and implicitly bisexual Hodiak, and the most charged relationship of all: the daughter-mother (Mary Astor) conflict that runs straight and crooked through all but the film's final pairing. Along the way, the voice also analyzes the film's running "fashion-show" of everyday sportswear; the pre-film build-up of the Scott-Lancaster romance; why a film of this kind is in color; and the character of Johnny (Wendell Corey), explicitly a homosexual, who warns Scott away from Hodiak for reasons that the text does not even try to hide.

It is possible to argue, or to recognize, that the kind of close textual reading of an individual film that began with Cahiers du Cinéma 's Young Mr. Lincoln , and includes quite a few stops along the way, comes to an end, or at least to a serious cessation, with Ehrenstein's article.

Stepin Fetchit Talks Back

Joseph McBride

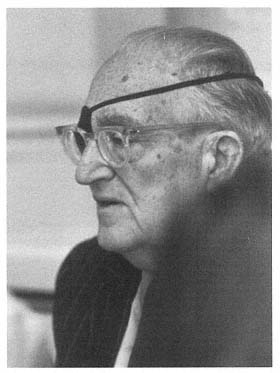

Stepin Fetchit (sometime in the 1930s).

Courtesy of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

Vol. 24, no. 4 (Summer 1971): 20–26.

To militant first sight, Stepin Fetchit's routines—all cringe and excessive devotion—seem racially self-destructive in the rankest way, and his very name can be a term of abuse. And yet, in looking at his performances (for instance as the white judge's sidekick and looking-glass in Ford's The Sun Shines Bright) cooler second sight must admit that Stepin Fetchit was an artist, and that his art consisted precisely in mocking and caricaturing the white man's vision of the black: his sly contortions, his surly and exaggerated subservience, can now be seen as a secret weapon in the long racial struggle. But whatever one makes of Stepin Fetchit's work, he was one of the few nonwhites to achieve status in American films, and he deserves to be remembered .

Like all American institutions, Stepin Fetchit is having a hard time these days. The legendary black comedian, now 79 years old but looking decades younger, has found himself a target of ridicule from the very people he once represented, almost alone, on the movie screen. A revolution has erupted around him, and he has been cast not in the role of liberator (as he sees himself), but as a guard in the palace of racism. The man behind the vacant-eyed, foot-shuffling image is Lincoln Perry, a proud man embittered by scorn and condescension.

Once a millionaire five times over, he now lives modestly in Chicago and takes an occasional night club gig. He hasn't acted in a movie since John Ford's The Sun Shines Bright in 1953, though he appeared in William Klein's documentary about heavyweight champion Muhammad Ali, Cassius le Grand , while acting as Ali's "secret strategist" during the Liston fights. Perry once served in a similar capacity for Jack Johnson, and Ali's gesture of kinship has given a massive boost to the comedian's self-esteem.

I encountered him in a garish bottomless joint in Madison, Wisconsin, on the night of Ali's fight with Oscar Bonavena. Before we talked, I sat down to watch his 20-minute routine, which was sandwiched on the program between Miss Heaven Lee and Miss Akiko O'Toole. Audiences at these Midwestern

nudie revues behave like hyenas in heat, but there is one very beautiful thing about a place like this, and I mean it: nowhere else in America today will you find such a truly democratic atmosphere. Class distinctions vanish as hippie and businessman, hard-hat and professor, white and black and Indian and Oriental unite in a common impulse of animal lust. Women's liberationists would object, of course, but not if they could observe the audience at close range—Heaven Lee had us enslaved.

When Step appeared, in skimmer and coonskin coat, there was a wave of uneasy tittering, and his first number, an incomprehensible boogie-woogie, stunned the audience into silence. What's this museum piece doing out there? Better he should be stored away where we can't think about him. But as he launched into his routine, a strange thing happened. Slowly, gradually, people began to dig him. Stepin Fetchit is, first and last, a funny, funky man. It isn't that his jokes are so great (a lot of them were tired-out gags about LBJ, of all people), it's the hip way he plays them. What made Step and Hattie McDaniel outclass all the other black character actors of bygone Hollywood was their subtle communication of superiority to the whole rotten game of racism. They played the game—it was the only game in town—but they were, somehow, above it: Step with his otherworldly eccentricities and Hattie McDaniel with her air of bossy hauteur . A tableful of young blacks began to parry back and forth with Step as he talked about the South. "You know how we travel in the South?" "No, how we travel in the South?" "Keep quiet an' I tell you." "That's cool. That's cool." And Step drawled: "Fast. At night. Through the woods . On top of the trees ." The irony may have been a shade too complex for the rest of the audience, but everybody understood when he laconically gave his Vietnam position—"Flat on the ground"—and explained the situation of the black voter: "Negroes vote 20 or 25 times in Chicago. They don't try to cheat or nothin' like that. They just tryin' to make up for the time they couldn't vote down in Mississippi. When you in Mississippi you have to pass a test. Nuclear physics. In Russian. And if you pass it, they say, 'Boy, you speak Russian. You must be a Communist. You can't vote.'"

Out flounced Akiko, and we went downstairs to a dusty storage area which had been hurriedly transformed into a dressing room. Stepin Fetchit may be funny, but Lincoln Perry isn't. "Strip shows are taking over everything," he lamented. "You're either at the top or you're nothing." The stage he was using, a rectangular runway, forced him to turn his back on half of the audience, and he was trying to improvise a new means of attack. (It was sad and strangely appropriate that the lighting was so bad he had to carry his own spotlight around with him.) His heart, moreover, was with Ali. "That's where I should be, with that boy," he said. Jabbing his finger and circling me like a bantamweight boxer, Perry quickly turned the interview into a monologue.

Under a single swaying light bulb, the sequins on his purple tuxedo flashing, he moved in and out of the shadows like a restless ghost. I began to get the eerie feeling that I was serving as judge and jury, hearing the self-defense of a man accused of a cultural crime. This is what the man said:

I was the first Negro militant. But I was a militant for God and country, and not controlled by foreign interests. I was the first black man to have a universal audience. When people saw me and Will Rogers together like brothers, that said something to them. I elevated the Negro. I was the first Negro to gain full American citizenship. Abraham Lincoln said that all men are created equal, but Jack Johnson and myself proved it. You understand me? I defied white supremacy and proved in defying it that I could be associated with. There was no white man's ideas of making a Negro Hollywood motion picture star, a millionaire Negro entertainer. Savvy? I was a 100% black accomplishment. Now get this—when all the Negroes was goin' around straightening their hair and bleaching theirself trying to be white, and thought improvement was white, in them days I was provin' to the world that black was beautiful. Me . I opened so many things for Negroes—I'm so proud today of the things that the Negroes is enjoying because I personally did 'em myself.

People don't understand any more what I was doing then, least of all the young generation of Negroes. They've made the character part of Stepin Fetchit stand for being lazy and stupid and being a white man's fool. I never did that, but they're all so prejudiced now that they just can't understand. Maybe because they don't really know what it was like then. Hollywood was more segregated than Georgia under the skin. A Negro couldn't do anything straight, only comedy. I did more acting as a comedian than Sidney Poitier does as an actor. I made the Negro as innocent and acceptable as the most innocent white child, but this acting had to come from the soul . They brought Willie Best out there to make him an understudy for me. And he wasn't an actor, he wasn't an entertainer or nothin' like that. I didn't need no understudy, because I had a thing going that I had built my own. And the worst thing you'll hear about Stepin Fetchit is when somebody tries to imitate what I do, the first thing they're gonna say is "Yassuh, yassuh, boss." I was way away from that.

Do I sound like an ignorant man to you? You made an image in your mind that I was lazy, good-for-nothing, from a character that you seen me doin' when I was doin' a high-class job of entertainment. Man, what I was doin' was hard work! Do you think I made a fool of myself? Maybe you might want me to. Like I can't be confined to use the word black. For a comedian, that takes the rhythm out of a lot of jokes and things. So when I use the words colored and Negro I'm not trying to be obstinate. That's what I'm going around for—to show the kids there are a lot of people that's doin' things to confuse them.

I'm just trying to get the kids today to have the diplomacy that I had to when I was doing it, and I think they'll come out first in everything. I didn't fight my way in—I eased in.

Humor is only my alibi for bein' here. Show business is a mission for me. All my breaks came from God. You see, I made God my agent. Like it's a coincidence that I'm here talking to you now. They bring a lot of people here, they pay 'em to talk to these students. They teachin' these students to go against law and order, they teachin' 'em to go against God, against their country, and they're payin ' 'em. They wouldn't pay me to come to town to talk to the students. Are you one of these college boys? No? That's good. All these college boys, the first word they think of when they write about me is Uncle Tom. I was lookin' for the word to come up but it didn't. Uncle Tom! Now there's a word that the Negro should try to wipe out and not use. Uncle Tom was a fictional character in a story that was wrote by Harriet Beecher Stowe. And Abraham Lincoln said that this thing was one of the propaganda that put one American brother against his other.

Kids is eccentric. They think they want to hear all these eccentric things. Like I see beautiful kids—I went to a place near where I'm working called the Shuffle and the reason they're using all this long hair and these whiskers, looking like apostles, that's because they're leanin' towards God, instinctively. Good kids, and a lot of old men is foolin' 'em. I want to let 'em know how I as a kid, a small Negro kid that was a Catholic too—so I had eleven strikes against me in them days—became a millionaire entertainer. Now these kids, they think that I'm unskilled and I'm uneducated, you know, and I don't have no diplomas or anything like that. But they must remember that they're listening to 79 years of experience.

I was an artist. A technician. I went in and competed among the greatest artists in the country. When I was about to make a movie with Will Rogers, Lionel Barrymore went to him and said, "This Stepin Fetchit will steal every scene from you. He'll steal a scene from anything—animal, bird, or human being." That was Lionel Barrymore , of the Barrymore family!

John Ford, the director, is one of the greatest men who ever lived. We was at the U.S. Naval Academy in 1929 making a picture called Salute , using the University of Southern California football team to do us a football sequence between the Army and the Navy. John Wayne was one of their football players. And in order to be seen by the director at all times, because Ford wanted to make him an actor, John Wayne taken the part of a prop man. That director made him a star. And on that picture, John Wayne was my dresser! John Ford, he was staying in the commandant's house during that picture, and he had me stay in the guest house. At Annapolis!

I was in Judge Priest , that Ford did with Will Rogers in 1934. Did you see that? Well, remember that line Will Rogers says to me, "I saved you from one

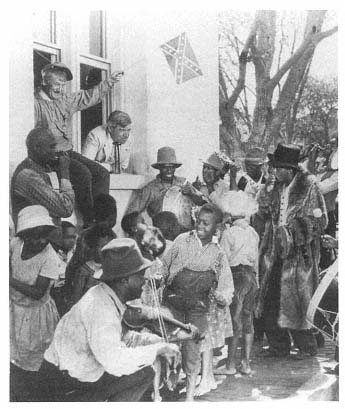

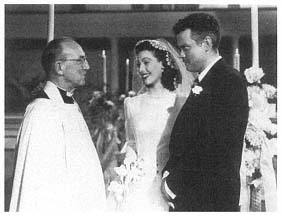

Stepin Fetchit (on right, with coonskin coat) as Jeff Poindexter in

John Ford's Judge Priest (1934).

Courtesy of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

lynching already"? We had a lynching scene in there, where I, as an innocent Negro, got saved by Will Rogers. They cut it out because we were ahead of the time. In 1953 we did a remake of that picture, called The Sun Shines Bright . And John Ford, he did the lynching scene again. This time the Negro that gets saved was played by a young boy—I was older then. But they kept it in. That was my last picture.

I filed a $3 million lawsuit against something that Bill Cosby said about me in a show called Of Black Americans . But I didn't make Cosby a defendant. Know the reason why? Because that's not the source of where the wrong come. It's CBS, Twentieth Century–Fox, and the Xerox Corporation, the men that sponsored it, that's responsible for distortin' my image. Cosby was just a soldier. He was not a general. I know all the black comedians. Bill was the onliest one I hadn't met. I met him for the first time in Atlanta at the Cassius Clay–Jerry Quarry fight. Cassius called me and say, "Hey, Step, I want you to meet Bill." I just said hello, because I was busy, and then he said, "Bill Cosby! " I went back and I say, "Well, Cosby, I hope that you help to put a happy ending to my damages that has been

done." He says to me, "Yeah, I told my wife, I hope that you win this suit, because it was taken out of context." Cosby's a great comedian, but for the educated classes. Savvy? A few years ago he wouldn't have been able to be where he is—I was the one who made it possible for him. The worst thing in America today is not racism. It's the way the skilled classes is against the unskilled classes. You understand me?

Now, if we don't get this country straight, your next president is going to be George Wallace. They figure everybody is being turned idiot and they gonna all agree it's gonna be a man like George Wallace to help our problems if we don't straighten them out ourselves.

Ain't but two things in the world today. That's good and bad, right and wrong. Now if we follow everything down to them two things, and we are either on one of them sides, it ain't no white, no colored, no Black Panthers, no Ku Klux . . . we either for good or for bad! We ought to have a National Association for the Advancement of Cre ated People and not think about each nationality that represents 50 percent of America. When God made Adam, he didn't make all these different nationalities. Man did it. There is no mules in heaven. Now let me explain this to you. Mules are man-made, made from crossing a jackass with a horse. So when man got mixed up, it wasn't the work of God, it was the work of man. Racism? Remember when there wasn't but four people on earth, Cain killed his brother Abel and started unbrotherly love. God didn't have nothin' to do with unbrotherly love.

To show you how fate works—Cassius Clay, none of these great liberals would touch him and give him a chance to fight again. And who do you think give him a chance to fight again? Senator Leroy Johnson of Georgia, a man that is associated with Lester Maddox . Without Lester Maddox, Cassius Clay wouldn't have fought today, although the image they gave to you was that Lester Maddox was against it. You get the idea? You understand me? The greatest example of Americanism was shown to Cassius Clay by a proxy, through Lester Maddox! That's the way the world is running. So let's face these things right, not like we pitchin' things, or like we want it to go. God's gonna work in a mysterious way! We have had men supposed to be great all down the line—Alexander, Moses—and we still found the world all messed up. Ain't nobody in good shape. Ain't nobody got no sense or nothin'.

It was Satchel Paige that opened the major leagues to the Negro ball players. Not Jackie Robinson. No suh! Satchel Paige did the dirty work. He used to go and play in counties where they didn't allow a Negro in the county. He did the good work—what I did—made good will and good relations. Jackie Robinson was the politician, you understand me, the skilled one that walked in and got the benefits. Satchel Paige broke down the whole deal and hasn't got credit for it yet, just because he was unskilled labor. He was 100 years ahead of his time, like I am, like Johnson was.

The reason why Cassius sent for me was because he found out that I was the last close intimate of Jack Johnson. Jack told me a lot of things. Cassius always said they wasn't but one fighter that was greater than him, and that was Jack Johnson. And so he wanted to know everything about him. He got me in and he would ask me all the different things that Jack would tell me about. I taught him the Anchor Punch that he beat Liston with—that was a punch that Jack improvised. Cassius dug up some pictures of Johnson and I told him about this out-of-sight punch that Jack Johnson said he had. He said he could use it any time he wanted on Willard. See, Willard did not knock Johnson out. Johnson sold the heavyweight champion of the world for $50,000. Johnson accepted $15,000 in Europe and told them to give his wife $35,000 at ringside. He wanted the heavyweight champion title to belong to America. They had ran Jack into a lot of things, you get the idea . . . be too long to talk about.

They promised him with the $15,000 they would wipe off this year that he's supposed to serve. But they didn't do that, so he came back and served the year himself. You get the idea? I saw that play, The Great White Hope . I think it's terrible as far as telling the truth about Jack Johnson. It's not about Jack. Jack Johnson had noble ideas. They had him beating this girl—Jack never did a thing like that. And they showed where he was defeated and knocked out, but they didn't show that he sold out the heavyweight champion and that he wanted the championship to belong to America.

We were going to do this picture of his life story, called The Fighting Stevedore . You know—from Galveston, Texas, where he used to be a stevedore. While we was waiting to write the story—we was making it just for colored theaters, in them days things weren't integrated and the big companies wouldn't want to buy it because everything had thumbs down on Jack Johnson like things tried to be with Cassius, although I'm sure Cassius is coming out of it—while we was waiting to write this thing, we sent Jack down to lead the grand parade of Negro rodeos in Texas. That was the trip he got killed on. I booked him on it.

I always call Cassius "Champ" because I used to call Jack Johnson "Champ." The way Jack and me met, we was both celebrities, and I used to sit in his corner when we was fighting. We became friends especially when he found out that the same priest had taught both of us. His name was Father J. A. St. Laurent. He taught also the Negro student that became the first Negro Catholic priest in America. Here's a picture of me preachin' to Martin Luther King. I was telling him that I was in Montgomery, Alabama, before he was born playing with white women. This priest was the head of the school I went to, St. Joseph's College. It was a Catholic boys' school. And this priest used to have the nurses come from St. Margaret's Hospital to play with us—that's where Mrs. George Wallace was a patient before she died. They had picnics, spent a

whole day on our campus with these colored boys, playing ball with us, eating in our dining room, and things like that. This priest he taught us a technical education—Tuskegee used to teach manual labor—and so he left those boys with something. We had no inferiority complex. Jack always wanted to show that all men were created equal, so he goes into Newport News society and married a white woman out of the social register, a blue-blood!

My father named me Lincoln Theodore Monroe Andrew Perry. Told me he named me after four presidents—he think I'm gonna be a great man. But I can't see how in the world he named me after Theodore Roos evelt. He wasn't even president yet! I was born in 1892—here's my birth certificate—in Key West, Florida, the last city in the United States. I'm a descendant of the West Indies. My mother was born in Nassau, my father was born in Jamaica. I had talent all my life—my father used to sing. He was a cigar maker. I got in show business in 1913 or '14. The people who had adopted me and sent me off to this school, something happened to them, and so this priest told me I could work my way through school. In summertime he let me go to St. Margaret's Hospital to work. When time to go back to school, there was a carnival that used to winter in Montgomery. Turned out to be the Royal American Shows. So I joined it, joined the "plantation show." The plantation shows started to call themselves minstels, but minstrels was white men made up. Plantation shows was black men made up.

I got my name Stepin Fetchit from a race horse. The plantation show minstrels, we went down in Texas and there was a certain horse we used to go and see at the fair. We knew these races because they went to the same fairs as we did. There was a horse that we knew would never lose, so we would go out and give the field and the odds. Well, people thought we was crazy—he would always win. But one day they entered a big bay horse on us, and he won. We went and grabbed the program, looked, and it was Stepin Fetchit, horse from Baltimore. And so I goes back to show business in Memphis, and hear "Stepin Fetchit! Stepin Fetchit!" from everyone. I wrote a dance song of it called "The Stepin Fetchit, Stepin Fetchit, Turn Around, Stop and Catch It, Chicken Scratch It to the Ground, Etc."

Me and my partner was introducing this new dance. We were Skeeter and Rastus, The Two Dancing Crows from Dixie. Jennifer Jones's father booked us in a white theater in Tulsa, Oklahoma, which was unusual. And in place of putting our names Skeeter and Rastus, he put Step and Fetchit and he made that our names. When my partner, he wouldn't show up, I would tell the manager, "No, it's not two of us, it's just one of us, the Step and Fetchit." And then I'd go out and do just as good as the two of us. I fired him, since I had wrote the song, see, and in place of The Two Dancing Crows from Dixie, I was the Stepin Fetchit. I got the lazy idea from my partner. He was so lazy, he used to call a cab to get across the street.

I was in Ripley's "Believe It or Not" as the onliest man who ever made a million dollars doing nothing. Anything money could buy, I had. I had 14 Chinese servants and all different kinds of cars. This one, a pink Rolls Royce, it had my name on the sides in neon lights. My suits cost $1,000 each. I got some of them from Rudolph Valentino's valet after he died. I showed people that just because I had a million dollars, the world wouldn't come to an end. But then I had to file a $5 million bankruptcy and didn't have but $146 assets. No, I wasn't held up by no robbers, and I wasn't in any swindling gambling games. It was all "honest" business people I trusted who took the money, all good, upstanding people. I was too busy makin' it to think about savin' it. I started with nothin' and I got nothin' left, so I've come full circle. But I'm rich. I'm a millionaire. Know the reason why? Because I go to Mass every morning. I have been a daily communicant for the last 50 years. Everything I've accomplished I've accomplished in believin' that seek ye first the kingdom of heaven and all things will be given to thee. Consider the lilies of the field . . .

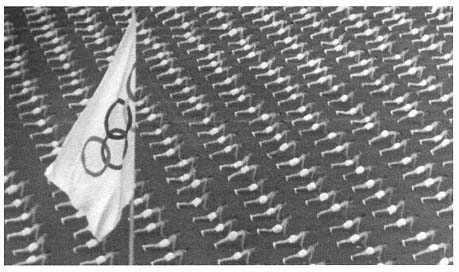

Footnote to the History of Riefenstahl's Olympia

Hans Barkhausen

Vol. 28, no. 1 (Fall 1974): 8–12.

Leni Riefenstahl has maintained that her two 1936 Olympics films, Fest der Völker and Fest der Schönheit , were produced by her own company, commissioned by the organizing committee of the International Olympic Committee, and made over the protest of Nazi Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels. In "Olympia, the Film of the Eleventh Olympic Games in Berlin, 1936," a paper written to defend herself in 1958, she says: "The truth is that neither the Ministry of Propaganda nor other National Socialist party or government bodies had any influence on the Olympic Games or on the production or design of the Olympia films."

The voluminous documentary material of the former Ministry of Propaganda and Public Enlightenment and the materials of the former Reich Ministry of Finances, today deposited in the Federal Archives in Koblenz (the central depository of the Federal Republic of Germany), tell a different story.

These records show that the two Olympia films were financed by the Nazi government, that the Olympia Film Company was founded by that government, that the government made money by distributing the films through the Tobis-Filmkunst Company, and that the government, finally, ordered the liquidation of the Olympia Film Company, in which Leni Riefenstahl and her brother were partners.

The true story of the origin of the two Olympics films of 1936 begins with a short memo written in the Reich Finance Ministry on October 16, 1935, saying: "On the order of Herr Minister Goebbels, Ministerial Counselor Ott, on October 15, proposed the following special appropriations to me: (1) for promotion of the Olympic Games: RM 300–350,000; (2) for the Olympic film: RM 1,500,000."

Ministerial Counselor Ott was the budget expert in the Propaganda Ministry, much respected, and rather liberal by the standards of the times. A carbon of the memo was sent to him by the Finance Ministry, and he initialed it on October

17, 1935. The words "to me" evidently refer to the section chief in charge in the Finance Ministry; his name in the note is recorded only by his initial "M."

The memo continues, with reference to point (2), that is, the Olympic film:

The Ministry of Propaganda submits the draft of a contract for the production of a film of the Olympics, according to which Miss Leni Riefenstahl is commissioned to produce a film of the summer Olympics. The cost is budgeted at RM 1,500,000.

I have pointed out that this film is certain to bring revenue, so that there would be no difficulty in financing the costs by private enterprise, for example by the Film-Kredit-Bank. This method would avoid government financing. But Ministerial Counselor Ott replied that Herr Minister Goebbels requests the prefinancing with government funds.

According to information from Ministerial Counselor Ott, Herr Minister Goebbels will request the proposed funds in the cabinet meeting of October 18, 1935. [Emphasis in the original.]

This is what actually happened.

In the contract mentioned in the memo Leni Riefenstahl is commissioned to produce and direct the film of the Olympics. The contract repeats the costs of RM 1,500,000. This amount was to be disbursed in four installments:

RM 300,000 on November 15, 1935

RM 700,000 on April 1, 1936

RM 200,000 on November 1, 1936

RM 300,000 on January 1, 1937

We shall soon see that these amounts were not enough to produce the film.

Section 3 of the contract with Riefenstahl says:

"From the amount of RM 1,500,000 Miss Riefenstahl is to receive RM 250,000 for her work, which is to cover expenses for travel, automobile, and social affairs." The contract stipulated—and this turned out to be an important provision—that Leni Riefenstahl was "to account to the Reich Ministry for Propaganda and Enlightenment for the disbursement of the RM 1,500,000 by presenting receipts." The contract specifically reconfirms that "she is solely responsible for the general artistic direction and overall organization of the Olympic film."

In her 1958 defense paper she writes: "On higher orders (Dr. Goebbels), the German news cameramen, who were the most important elements in the making of documentary pictures, were removed from Leni Riefenstahl's control."

Section 6 of the contract says:

"The Reich Ministry for Propaganda and Public Enlightenment undertakes (as previously in the production of the Reich Party Day film Triumph des Willens ) to place the German weekly news shows [Wochenschauen ] of the Ufa, Fox, and Tobis at the disposal of Miss Riefenstahl and to obligate them to make accessible the material filmed by them for the Olympia film."

The amounts that Riefenstahl was to pay for this material were spelled out by the Propaganda Ministry.

I presume the Wochenschau companies were not enthusiastic about having their cameramen take orders from Riefenstahl. But Wochenschau material was in fact delivered to her, as shown by the "Itemized List for Herr Minister, April 1937." It states all costs incurred until then for the Olympia film, with a total of RM 1,509,178.09, which includes as item 11: "Raw film and Wochenschau material: RM 220,003.41." Whether Riefenstahl actually used this material in her film is a different question. But in her distribution contract with Tobis this possibility is specifically spelled out for legal reasons.

In her postwar interviews Riefenstahl consistently referred to "her own company" that produced the Olympia film. In her 1958 defense paper she also says: "Goebbels did not want Leni Riefenstahl to show the victorious black athletes in the Olympia film. When L. R. refused to comply with these requests and did not honor them later either, Goebbels ordered the Film-Kredit-Bank, which was answerable to his Ministry, to refuse all further credits to the Olympia-Film Company (a private firm)." The parenthesis is in the original. These statements, however, are products of Leni Riefenstahl's imagination. What are the facts?

When a film company was funded, it was general practice to deposit in a court of law an initial capital of RM 50,000, after entering the firm in the official Trade Register. The funds for the founding of the Olympia Film Company were provided by the Reich government. But the Reich, in this case, was parsimonious. Hence Ministerial Counselor Ott, on January 30, 1936, wrote to the Berlin-Charlottenburg Court: "The Olympia Film Company is being set up at the request of the government and financed by funds supplied by the government. The means needed by the company to produce the film are likewise supplied exclusively by the government. The company has had to be established because the government does not wish to appear publicly as the producer of this film. It is planned to liquidate the company when the production of the film is concluded."

Evidently this was still not spelled out with sufficient clarity for the Court. Therefore the Reich Film Chamber, the body responsible for the founding of film companies, wrote to the Court on February 12, 1936: "We are not talking, then, about a private enterprise, or about an enterprise with ordinary commercial aims, but about a company founded exclusively for the purpose of external organization and production of the said film. It appears unwise [untunlich ] for

the government itself to appear as the producer." Hence Leni Riefenstahl's fictitious company was required to pay no more than RM 20,000 as original capital, from the funds provided by the government. Still, the Examination Board of the Propaganda Ministry complained on October 16, 1936, that "the original capital has not been paid in up to now."

The report of the General Accounting Office which contains these words was an embarrassment for Riefenstahl which she never got over. It was probably one reason why she hated the Propaganda Ministry. Hence I will have to discuss that report further.

The auditors of the GAO, like those of any official agency, even in the Third Reich, were petty bureaucrats. The GAO had tackled audits for other agencies of the government, but presumably it had never dealt with a film production, and certainly never had to deal with such a temperamental and self-assured film artist as Riefenstahl. The auditors, however, chose to treat her strictly as the manager of the Olympia Film Company.

The auditors complain that as early as September 16, 1936, of the government-agreed RM 1,500,000 "RM 1,200,000 were requested by the Company and paid out, although by that time only RM 1,000,000 were due." They complain further that "the use of these funds contradicts the order concerning government economies to administer official funds economically and carefully." They add that there were no economies "in general expenses such as per diem payments, tips, meals, drinks, charges, and special charges." "Rarely," they say, "was there a meeting in which the company did not pay for breakfast, lunch, or dinner." The auditors take issue with the fact that the Geyer Works, where Riefenstahl edited the Olympia film and had it printed, on the occasion of its business anniversary was presented with two flower baskets and a gift, valued together at RM 117; that the firm paid RM 202.40 for a business course attended by Leni Riefenstahl's secretary; that RM 10.17 was paid without specification for the "Reich Race Research Office"; that "Miss Riefenstahl and her business manager Grosskopf were reimbursed RM 18 and 15.75 for lost fountain pens." It goes on in this way for pages—thousands of bills or receipts were examined, and where the auditors saw fit were commented on. A few passages read like comedy: those administering money are chided by the sentence: "The company has no strongbox." Business manager Grosskopf, being responsible for the safety of the cash, "was obliged to take the money home with him" and during the examination on October 3, 1936, "had produced RM 14,000 to 15,000 in various amounts from different pockets of his clothing." The outraged auditors state: "Such practices are verboten."

Incidentally, I happen to know Grosskopf and met him on occasion during the months when the Olympia film was in production. He was a solid, conscientious older businessman, visibly bothered by a situation that was beyond his control.

Goebbels treated this report, presented to him by Ministerial Counselor Hanke, chief of the Ministerial Secretariat (later Gauleiter in Breslau), far more generously than Riefenstahl will allow today. With a green pencil he wrote across the report "Let's not be petty" and ordered Hanke to talk with Riefenstahl. However, when Ministerial Counselor Ott presented Goebbels with an additional request for RM 500,000 because the RM 1,500,000 "presumably will not be sufficient," he wrote: "RM 500,000 are out of the question." But one can sense that this phrasing left the door open. At any rate, he approved an additional RM 300,000.

He refused Ott's suggestion "to include the Film-Kredit-Bank in the future, because it can factually check on the expenditures of the Olympia Film Company," but shrewd Ott has added to his suggestion: "One will have to assume, of course, that Miss Riefenstahl will fight such an order with all means at her disposal." Besides, observes Ott, "it could be undesirable for a private firm, such as the Film-Kredit-Bank, to have intimate information about a company entirely set up by the government." He suggests that perhaps the Reich Film Chamber should do the auditing.

It was undoubtedly disconcerting for Riefenstahl to have to answer the various criticisms of the auditors. Her annoyance was understandable; but there was a second reason to be annoyed. Goebbels ordered the Reich Film Chamber to make available "Judge Pfennig of the Reich Film Chamber as advisor to the Olympia Film Company." He was to ensure the "purposeful and economic use of the means of this company." The Reich Chamber, on its part, was to report to him, Goebbels, "about Judge Pfennig's activities and observations." Goebbels signed this order with his own hand.

Pfennig was the Legal Counsel of the Reich Film Chamber. Earlier he had worked for the major German film producing company, the Ufa. After Hugenberg in 1927 had taken over the Ufa and had appointed the Director General of the Sherl Publishing Company, Ludwig Klitzsch, as Director General of Ufa, economy was demonstrably practiced. As early as April 1927 Klitzsch appointed Pfennig, then a law clerk, as director of his secretariat and informed the Board of Directors accordingly (Ufa, Board of Directors protocol No. 18, April 28, 1927). Klitzsch, however, could economize only as long as Goebbels would let him. But after about 1937 Goebbels increasingly prevented economy. It must have been Leni Riefenstahl's second great grief to have Judge Pfennig appointed to supervise her, even though disguised as observer.

In her paper of 1958 Riefenstahl says that she concluded a distribution contract with Tobis, but this tells little about the ownership of the Olympia Film Company. A government-owned company needed a distribution contract just as much as a privately owned one. The contract, concluded December 4, 1936, between Olympia Film Company, represented by Leni Riefenstahl, and Tobis-

Olympia

Cinema Company, represented by production chief Fritz Mainz, specifically points out that the production costs will be about RM 1,500,000. Tobis agreed to a guarantee for RM 800,000 for the first part and at least RM 200,000 for the second part of the film. What this contract did not mention, however, was the obligation by Tobis to account not only to Olympia Film Company but also to the Ministry of Propaganda. This was duly done, however; one copy of the accounting went to Olympia Film Company and two copies to the Ministry of Propaganda, one of which was routed to Ministerial Counselor Ott.

It took Leni Riefenstahl eighteen months to complete the two films, a period of time envisioned by the contract with Tobis. The première took place on April 20, 1938, Hitler's 49th birthday, at Ufa Palace at the Zoo in Berlin in festive surroundings. There was no indication of a rift between Goebbels and Leni Riefenstahl, such as she has talked and written about.

As early as September 26, 1938, Ministerial Counselor Ott was able to report to the Ministry of finance that "a million Reichsmark of unplanned revenue have flowed into the coffers of the Reich treasury."

At that time the Rechnungshof (General Accounting Office) remembered that the understanding had been to liquidate the Olympia Film Company on the completion of its task. On November 5, 1938, the agency inquired of the Reich Minister for Propaganda and Public Enlightenment "when the liquida-

tion of the Olympia Film Company is to be expected." On November 21 the reply came, saying that "according to present developments the end of business is to be expected in fiscal year 1939."

Barely six months later, on May 17, 1940, that is, after the start of the war, the Propaganda Ministry was able to report to the Reich Finance Ministry that the RM 1,800,000, "needed for the production of the Olympia films and advanced by the government, had been repaid in full to the Reich." The liquidation of the Olympia Film Company, the report added, had been decided in a company meeting on December 6, 1939, to be effective December 31; the liquidation was to be carried out by business manager Grosskopf. Future revenues from the film would "as up to now be paid into a holding account of the Reich Treasury."

The liquidation process, in fact, took two more years. In the middle of Hitler and Goebbels' "total war," the tireless Ministerial Counselor Ott, still in the same position at the Propaganda Ministry (remarkable in view of the frequent changes in other departments of the agency), on February 1, 1943, reported to the Reich Finance Ministry that "the liquidation of the Olympia Film Company has been completed." According to the accounting submitted "the total net gain transferred to the Reich amounted to RM 114,066.45."

When a king dies another must be immediately proclaimed; hence the final paragraph states: "The further utilization and administration of the two films of the Olympics have been transferred to the Riefenstahl Film Company [my emphasis], which will report quarterly about the financial status." No inkling, indeed, of hostility between Propaganda Ministry and Riefenstahl.

Thanks to Adolf Hitler the German Reich has ceased to exist, but Leni Riefenstahl is still permitted to exploit her two Olympia films of 1936/1938. She does so now on the basis of a thirty-year contract concluded ten years ago between her and the Transit Film Company, which administers the film rights of the German Federal Republic. Of course, from time to time, she has to settle accounts.

Power and Dis-integration in the Films of Orson Welles

Beverle Houston

No movie is made by a complete adult. First of all, I don't know any complete adults.

Orson Welles

I, señor, am not one of anything, but, like you, señor, I am unique.

The Second (Dying) Art Forger, to Picasso, in F for Fake

Vol. 35, no. 4 (Summer 1982): 2–12.

I should like to thank the UCLA film archive for its generous cooperation in providing me access to these films.

In a scene of snowfall before a small house, Charles Foster Kane is cast out of his family by his newly rich mother. As generations of moviewatchers are well aware, it is to this snow scene that he returns upon his death as the text itself returns to the "No Trespassing" sign. In Magnificent Ambersons , on the other hand, family and friends spend years trying unsuccessfully to dislodge Georgie Minafer from the family mansion and the bosom of his mother. When the infant is finally forced out, he breaks both his legs. In the same film, Lucy Morgan is forced by Georgie's refusal to enter the world of men and money to return to her father and a lifetime of celibacy. Mary Longstreet in The Stranger is forced into a similar return.

Both Citizen Kane and Magnificent Ambersons reveal a central male figure who is extremely powerful in certain ways, who can charm, force, or frighten others into doing what he wants. But the desire for control is haunted by everything that evades it. The opening of Citizen Kane , with its decayed golf course and terraces, its moss-covered gothic magnificence, reveals to us two aspects of this pattern: both the overreaching ambition and its failure—a grand life, now in ruins. Even at the height of their powers, these men are revealed to be helpless in certain realms of life, unable finally to live out their desires. Focusing on Citizen Kane, Magnificent Ambersons , and The Stranger as family-centered narratives set in the United States, with substantial reference to Touch of Evil, Immortal Story , and Chimes at Midnight for close parallels of theme and/or narrative strategies, and with passing glances at a number of other Welles films, this essay will examine the ways in which the boundless fear, anger, and desire of these figures power both narrative and image in these films.

In my own years of obsession with the Welles films,[1] I have come to call this central figure of desire and contradiction the Power Baby, the eating, sucking, foetus-like creature who, as the lawyer at the center of The Trial , can be found baby-faced, lying swaddled in his bed and tended by his nurse; who in Touch of Evil sucks candy and cigars in a face smoothed into featurelessness by fat as

he redefines murder and justice according to desire; who in his bland and arrogant innocence brings everybody down in Lady from Shanghai; who, in the framed face of Picasso, slyly signals his power as visual magician and seducer and who is himself tricked in F for Fake; but who must die for the sake of the social order in Chimes at Midnight and who dies again for his last effort of power and control in Immortal Story; and who, to my great delight, is figured forth explicitly in Macbeth where, in a Wellesian addition to Shakespeare, the weird sisters at the beginning of the film reach into the cauldron, scoop out a handful of their primordial woman's muck, shape it into a baby, and crown it with the pointy golden crown of fairy tales.

Who are these infant kings who return to early scenes, whose narratives are deflected, and whose situations are finally reversed? What do they have, and what lack? How are they both more and less than they wish to be, sometimes never reaching, but more often losing their once-great powers in the world of men and money? And what is the pattern of possibilities for their women, who are so often denied or forced into returns, whose fates are so extreme, yet so limited?

The mother of Charles Foster Kane becomes rich and powerful in a moment of transformation. She uses this power to reject Charles utterly. He is ripped untimely from a scene where he could reach whatever combination of love, fear, acceptance, and rejection that might come from the child's living out the drama of sex and power with his parents. The untimeliness of this change is suggested perfectly by the exaggeration of size relations in the Christmas shot where Charles, with his unwanted new sled, gazes up defiantly at a huge Thatcher, the money monster, on that most familial of holidays, the one based on the birth of a perfect son into a perfect family.

In the name of what does Charles's mother commit this horribly wrenching act, for which she is so eager that she has had her son's trunk packed for a week? It is true that the father moves as if to strike Charles when he pushes Thatcher. And it is true that he says: "What that kid needs is a good thrashing," moving Mrs. Kane to reply: "That's what you think, is it; Jim? . . . that's why he's going to be brought up where you can't get at him." Apparently Mrs. Kane thinks he is "the wrong father" for little Charles. Yet we have little evidence that the father has ever harmed or frightened the child. As the four talk outside the cabin, Charles moves eagerly toward his father's arms; the mother must stop him by calling his name sharply. Thus it is one of the film's most powerful and puzzling images when, at the moment of her insistence, Mrs. Kane slowly turns her head to the side as the camera dwells on her enigmatic look. Is it one of confidence for having freed her son from a struggle he couldn't win? Or one of cruel pleasure in having triumphed over father and son for their very maleness? Is she the terrible mother of myth and nightmare? Joseph McBride suggests: "It is simply that the accident which made the Kanes suddenly rich has

its own fateful logic—Charles must 'get ahead.' What gives the brief leave-taking scene its mystery and poignancy is precisely this feeling of pre-determination."[2] It must be emphasized, however, that the logic is not that of fate but of money and social class. Insisting that "this isn't the place for you to grow up in," the newly empowered mother pursues her son's "advantages" by removing him from an impoverished rural environment. She turns her son over to an agency—the bank—that she believes will protect and promote him better than the family. Yet we cannot fully escape the hint of a revenge and must accept the overdetermination of this genuinely ambiguous moment.

The role of the father needs to be understood in a different way as well. It is not his cruelty that is most significant. The fact that Fred Graves, the defaulting boarder who knew both Mr. and Mrs. Kane, left the fortune exclusively to Mrs. Kane, somehow brings Charlie's paternity into question. Did Graves leave it all to Mrs. Kane because he found the father wanting in some way—weak and whining, dependent on his wife, perhaps? Or is it Graves himself, in his unpredictable act of generosity, who is the right ("real") father? Even though we are made sympathetic with Mr. Kane—"I don't hold with signing my boy away. . . . Anyone'd think I hadn't been a good husband. . . ." (Why doesn't he say, "Good father "?)—still other negative qualities are revealed. He first tries to get little Charles to believe that his forced migration from country/family to city/bank is going to be a wonderful adventure: "That's the train with all the lights. . . . You're going to see Chicago and New York. . . ." But when Charles refuses to be fooled, the father threatens to thrash him. Thus even this "wrong father" has two faces: he who promises deceitfully, who promises pleasure where there is abandonment, and he who later threatens violence. For the boy, the father becomes the promise of worldly experience and the threat of danger, both exaggerated. Longing to cling to the beloved but mysteriously rejecting mother, unable to trust the weak and deceitful father, the boy Charles reacts with rage as his life is captured in this frozen moment.

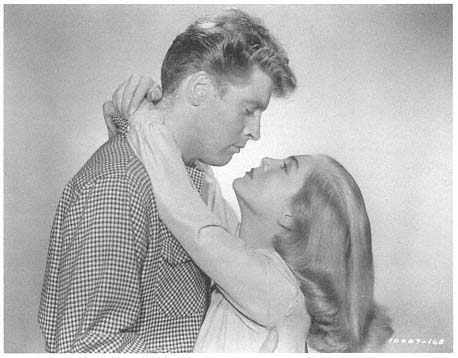

And what of Georgie Minafer, who got out, not too early, but too late? Within the basic reversal, there are a number of similarities, particularly concerning the father. In this film, money also brings about the constitution of the "wrong" family. The agency of business is this time substituted, not for the family as a whole, but for the emotional participation of the father through Isabel Amberson's choice of husband. She marries Wilbur Minafer, a "steady young businessman," instead of Eugene Morgan, "a man who any woman would like a thousand times better." Though the local women opine that Isabel's "pretty sensible for such a showy girl," they prophesy correctly the return of the passions denied by Isabel's choice: "They'll have the worst spoiled lot of children this town will ever see. It'll all go to her children and she'll ruin them." An only child receiving the full adoration of a mother who married for

"This nest of complete dependence and desire": The Magnificent Ambersons

dollars and sense, so puny he nearly dies as an infant, young Georgie also has a father who is virtually absent. Later, when the father dies, the voice-over narrator tells us: "Wilbur Minafer. A quiet man. The town will hardly know he's gone." And Georgie hardly knew he was there. But this time the young man with the wrong father, with no father to love and hate on a regular basis, has not been sent away by the mother. Instead, we find that Georgie lives fully in a mutual state of uncontested love with the mother, secure inside a warm, dark house and a rich and fabled family. No reason to get a job or a profession. No reason ever to leave this nest of complete dependence and desire.

The theme of the wrong or displaced father is explicit in Immortal Story as well, where the primacy of money (over friendship rather than passion this time) once caused old Mr. Clay to drive away his partner, the father of Virginie. When he brings her back to her father's house (which Clay now occupies) to play out her role in his fable of seduction, he functions as a cruel "wrong father" over whom she is able to triumph. Throughout the Welles canon, fathers and mothers are doubled and tripled, offering, through displacement, the multiplications and contradictions of identity and representation. Falstaff (Chimes at Midnight)

offers one of the richest and most fluid exercises in doubling and multiplicity of father/identity. Very early in the film we are presented with Falstaff as an old man who is at the same time an innocent, the one who has been shaped by the "son" he is supposed to have corrupted. As he tells us: "Before I knew thee, Hal, I knew nothing." Later on, Falstaff puts a pot on his head and plays the role of Hal's other father, the king, chastising the boy for his bad friends and wastrel's life. Then they change roles and Hal plays his own father, the king. All the way through the film, Hal's knowledge of his impending power as future king has run concurrent with his boyish playfulness and has made all his jokes and insults to Falstaff painfully cruel, as they now are in this exchange of roles. This cruelty is, of course, prophetic of his final assumption of a fixed identity as king, which entails the rejection of Falstaff after Hal has become his own father in earnest.

The main trajectory of the plot of Citizen Kane, Magnificent Ambersons , and The Stranger turns in on itself in the pattern of a return. The child/man, unable to continue his movement toward social participation and "maturity," falls back into a childhood situation, and the woman in The Stranger is forced into a similar return. In Citizen Kane , Charlie instantly defies his substitute father and the more or less innocent energy of this rebellion carries him well into young manhood. He travels, starts to run a newspaper, behaves like an aggressive young man in the world. This phase reaches a kind of peak in his "Declaration of Principles," where he lays down the law of the sons against the corrupt fathers of the money agencies (as Thatcher had earlier laid down the law of the "Trust" to his mother), his rebellious liberalism creating a link between the youthful and the poor. But he is not content to let the words and actions of the newspaper speak for themselves. He insists on foregrounding the enunciation, as it were, revealing himself as "author" of the newspaper, unmediated by an editorial persona. This authorial gesture is merely one of the ways that young Charles reveals his huge ambition. This boy, thrown out of many elegant schools, sees himself as becoming "champion of the people." His actions reveal the exaggerated picture he has of himself and his powers, which will later be revealed in the huge poster of himself at the rally, as he sets out to win everybody's love.

Love on a personal level reveals both his overarching aspirations and his limitations. The announcement of his engagement is read in a room full of statuary he has been sending to the office—"the loot of the world"—gifts given to no one, and never enough to fill the huge empty spaces that he and the others in his life will occupy as they grow older. In his bride to be, he has acquired another high element of culture—the president's niece. But like Isabel Amberson's, Charlie's attention is only briefly engaged by his new mate. McBride suggests that Charles has a need for affection that Emily "could not gratify," but I suggest that it is Kane who will not "gratify," turning from relations within his family to activities

in which he need function only as a source of verbal or financial power, where he is never called upon to act as husband/lover/personal father. (In Immortal Story , Mr. Clay tells us that he has always avoided all personal relations and human emotions, which can "dissolve your bones.")

One night, his uncharged marriage a boring failure, his vaunting political ambitions uncertain, Charles decides to make a return to the place where his mother's goods, and his own truncated development, lie in storage. But instead, he is splashed by mud and because of this accident, the return is delayed. He comments to Susan on this deflection: "I was on my way to the Western Manhattan Warehouse—in search of my childhood."

Georgie Minafer's dream-like intimacy with his mother (as signalled by the long, slow take and dark depth of field) is suddenly threatened by a second father (the "right father?"), Eugene Morgan, who has made a return of his own. Morgan has come back to the town of his romantic defeat to try again with the soon-to-be-widowed Isabel, bringing with him a daughter (the mother is never mentioned) and a number of transformations that will be devastating for Georgie, who clings to his fixed identity as an Amberson. Trying to resist Eugene in the world of men, Georgie is ineffectual because of such misconceptions. He overestimates the power of his family identity to guarantee his superiority (or, indeed, his survival). He is wrong when he tries to ridicule Gene's invention of the automobile, and wrong again when he tries to enlist his father against the usurper by absurdly accusing him of wanting to borrow money. But he is not wrong with his mother. Oh, no. With Isabel, practically all he has to say is: "You're my mother," and she agrees to call it off with Eugene, despite his plea not to allow their romance to be ruined by "the history of your own perfect motherhood."

As in Citizen Kane , it is a sudden and unexpected change of fortune—this time a loss—that finally breaks up the family. Georgie is faced with an entirely new situation. He is alone and must support himself. His mother has died of a nameless wasting disease, having been devoured by Georgie's ravening orality. (All these Power Babies eat and eat.)[3] Furthermore, his Aunt Fanny, who has been a kind of shadowy mother double, loving instead of being loved, seeking instead of evading, who has lived only to yearn after Eugene and to feed Georgie, is now completely dependent upon him. As he goes out in the world, one prospective employer notes that he has become "the most practical young man," but only very, very briefly. Praying at his mother's empty bed, the new Georgie begs forgiveness from the Father of Fathers, but no fathers hear, for in the next cut, Georgie has an accident. An automobile knocks him down and breaks both his legs.

Let us recall here that Kane's son was killed in an automobile accident (which also claimed his wife) and that maiming of the legs is common in the Welles

canon. Recall the extreme limp and double canes of Arthur Bannister in Lady from Shanghai , the greatly reduced mobility of Mr. Clay in Immortal Story , and perhaps most complex, the bullet in the leg that Quinlan took for his friend Pete Menzies in Touch of Evil . And if the leg wound can be taken as suggesting deflected or impeded sexuality, then we must note the role of Quinlan's cane in bringing about his downfall.

Georgie has always known where the danger lies. The first night he meets Eugene and Lucy, he denigrates the automobile and wishes her father would "forget about it." Later he scorns it as useless and, prophetically in more ways than one, says it should never have been invented. Georgie's insistent and perverse dismissal of this most powerful agent of transformation is, of course, thoughtless and superficial at the rational level; he appears foolish and self-defeating, moving his Uncle Jack to remark on how strange it is to woo a woman by insulting her father. But Georgie is reacting to the car as symbol of Gene's phallic power to take away the mother love on which Georgie sustains himself so voraciously and on which, as an untried emotional infant, he believes his life depends. While others enter into mature speculation about how the automobile will change the world—Eugene himself is most confident that it will: "There are no times but new times," he says—Georgie is terrified for his life. In his identity as a new man of the future, Eugene has benefitted from an exchange of power with the Ambersons; their great fortune is gone, their living space (the home, the woman's place) is taken away, while Eugene's fortunes rise, his factories and power transformers consuming the Amberson space and returning it as a city. To move from rural safety to urban danger, Georgie Minafer need only leave the house. In his own life and in the society at large, Georgie's world of women has given way to a world of men. This shift in economy threatens him at the deepest level. Georgie has begun to fear that he will soon take his "last walk," as the narrator puts it. In the reversal implied by his seeking a "dangerous job," Georgie signals us that his fear is becoming unbearably acute.

As the automobile accident fulfills Georgie's prophetic panic, he is returned to the state of complete dependency that marked his place in the family of origin. But this time, it is a strangely smiling Eugene Morgan upon whom he must depend. Worse than Georgie's worst fears, this outcome brings, not the death that might even be wished for, but a bitter substitute for the ecstatic plenitude of mother love. For Eugene, his rival/double, it constitutes a triumph.

As the new money and usurping father brought terror and helplessness to Georgie Minafer, they bring rage and isolation to Charles Foster Kane. Once a dirty accident has deflected him from his return and brought him together with Susan, their relationship takes a strange turn. Kane almost seems to act out the role of her mother. Susan's youth is established—"Pretty old. I'll be twenty-two

in August"—and we learn that her mother had operatic aspirations for her small, untrue voice. Immediately after this revelation, we see several of the film's few conventional, romantic close-ups as Susan declares sweetly: "You know what mothers are like," and Kane answers dreamily: "Yes, I know." The mention of the mother is linked with the sign values of shallow depth, key and back lighting, and slightly soft focus, signalling Romance even more strongly than the early scene with Emily, and suggesting that Susan has tapped into Kane's deepest desires—perhaps a fantasy of a mother staying with a child, watching over it and nurturing it, causing it to grow and flourish. Susan's reaction to this impossible program is another matter, to be spoken of later.

The meeting with Boss Jim Gettys, the other key encounter of Kane's life, turns upon the role of yet another father in the family and in culture. As his mother and Mr. Thatcher seemed to be in cahoots long ago against the little boy whose weak and unreliable father did nothing to help him, now another Mrs. Kane and another usurping father move to dislodge him once again from a place where he is perhaps living out all the roles of his frozen moment, but according to a new script of his archaic desires.

With inadequate experience of father and family to mediate between his infant rage and the world of signification, Kane has imagined his rival Gettys as a monster and put that monstrous image into the public realm—newspaper pictures of Gettys "in a convict suit with stripes—so his children could see. . . . Or his mother."[4] Now Gettys must wipe out the representational power of these images. To do so, he must discredit Kane completely. Thus Gettys as powerful and successful father and son punishes Kane, not for his transgression with Susan, which stands in for the move against the father and which might have stayed a childish secret forever, but for his unbridled excess in attacking Gettys so viciously in the newspaper. Even so, Gettys is formidable but not cruel, urging Kane to do his duty and avoid family disaster by withdrawing from the race. Finally, when Kane can do nothing but scream his child-like defiance, Gettys's words are those of the elder instructing the younger: "You need more than one lesson, and you're gonna get more than one lesson." Like Georgie's, Kane's comeuppance has swept over him suddenly in a wild moment.

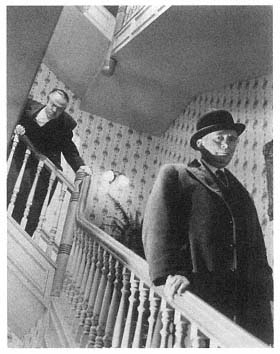

The image of Kane screaming down his impotent rage from the top of the steps suggests an attempt to reverse the size relations of the Christmas shot with Thatcher, and evokes similar images in a number of Welles's other films, most notably where his Macbeth, having destroyed a number of families, including that of the Kingdom itself, finally stands alone on the high wall, seeming to find a perverse ecstasy in his impotent defiance of Macduff, the outraged father (himself "untimely ripped") who has come to bring him down. In The Stranger , Charles Rankin, exposed as the Nazi Franz Kindler, screams down his defiance of Mr. Wilson, the Nazi-hunter/father figure, from the top of a clock tower.

Charlie Kane's impotent defiance of Boss Jim Gettys

Kane's destruction of the bedroom after Susan leaves is perhaps the most famous scene of rage in American film. Kane had tried to insert himself into the culture as a "celebrity" through public office—a space somewhere between that of a commodity and a well-known friend or family member. To the child of banks, being elected is perhaps like being loved. But his excess of anger cost him that public affirmation. Now the saving fantasy with Susan has failed, bringing on the wild rage. As he picks up the glass ball, Kane completes the return begun on that night when he started for the warehouse. We have already seen Kane in the newsreel with useless legs, swaddled in white like an old baby. The narrative will now offer no more events involving Kane before death causes him to release his frozen scene of trauma. After he passes through the hall of mirrors, the camera holds on the empty reflector; his identity is erased by its repetition. As Baudry says: "An infinite mirror would no longer be a mirror."[5] With his smooth head, pouting lips, and single tear, Kane is almost foetus-like, back in a primordial isolation before language, before family, before self.

As Susan walks away from Kane (and from her doll, seen in the extreme foreground as they quarrel, and seen again next to Kane's sled among the final images—he longed for his; she didn't long for hers) she also walks away from the return forced upon her by Kane. As indicated by her attempt at suicide, she

doesn't wish to continue as the child, living out her mother's fantasy or Charles's desire. Perhaps punished by her "alcoholism" for her aggressiveness in leaving Kane, certainly childishly imprudent in having spent all the money, Susan's real return has been to her position within another social class. But she is surviving, capable of working, playing, and feeling deep sympathy. Lucy Morgan in Magnificent Ambersons is also forced into a return, but a far more regressive one, and certainly of a different style. Georgie wouldn't enter the world of men and money, and Lucy certainly couldn't join him in the closed world of mother love. Therefore, as she tells him, "Because we couldn't play together like good children, we shouldn't play at all." In an idyllic out-of-doors scene, paralleling the one in which Morgan tried to convince Isabel to marry him, Lucy describes her situation to her father in the story of Ven Do Nah. This Indian was hated by all his tribe, so they drove him away. But they couldn't find a replacement they liked better. "They couldn't help it." So Lucy declares her intention to stay in the garden with her father for the rest of her life: "I don't want anything but you."

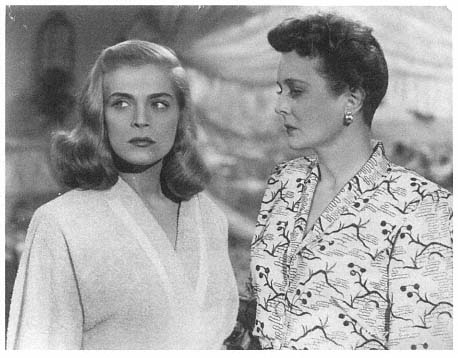

In several of Welles's films, a daughter, having made the wrong sexual choice, must return to the father. Perhaps the success of the fathers represents a displacement of the Power Baby's desired return, a metonymy in which the intensely longed-for power is muted as it moves into the quiet certainty and control of imagined patriarchal authority (yet another move in the representation of the diffuse subject). The most extreme version of the daughter's situation is developed in The Stranger . Mary Longstreet has chosen as her sexual partner not a dependent infant, not a half-baked crook like the daughter (of a white slaver) in Mr. Arkadin , but the worst possible enemy of everyone in the whole world—a NAZI! And how could this perfectly nice girl make this bizarre choice, which even her brother can't believe: "Gee, Mr. Wilson, you must be wrong. Mary wouldn't fall in love with that kind of a man." But Nazi-hunting father doubles like Mr. Wilson are not wrong. "That's the way it is," he later says, because "people can't help who they fall in love with." For "people," of course, read "women." (Remember Lucy and Ven Do Nah?)

This odd choice (and the presence of a Nazi in this New England town in the first place) can perhaps be understood by recognizing Kindler as representing difference, not only because he is a German, but in another way, because he is so closely associated with Mary. She is isolated in her connection with him. Only she has chosen him; only she supports him. In a strange way, he represents her insofar as she is one who makes a sexual choice. He is Mary's difference. For fathers, and for small-town America, this difference must be contained. In this deeply conservative film, Kindler's/Mary's difference must bring about his own downfall and her return. But his difference will also be recuperated. His exotic European hobby of fixing clocks will reinvigorate rural American tradition and law, as represented by the old town clock with its scenes of justice and revenge.

Control of the woman: The Stranger

Wilson neatly describes the trajectory of the film: "Mary must be shown what kind of man she married, even though she'll resist hearing anything bad about Charles." And despite this resistance, they are sure that her "subconscious" is their "ally," that deep inside her she has a strong "will to truth." This resource of unconscious health will, of course, lead her to relinquish her own willful difference and allow herself to be returned to her father. Thus family (again with no mother) and town will return to their original situation. A triumph of personal and social stasis.