3—

Circling the Scene

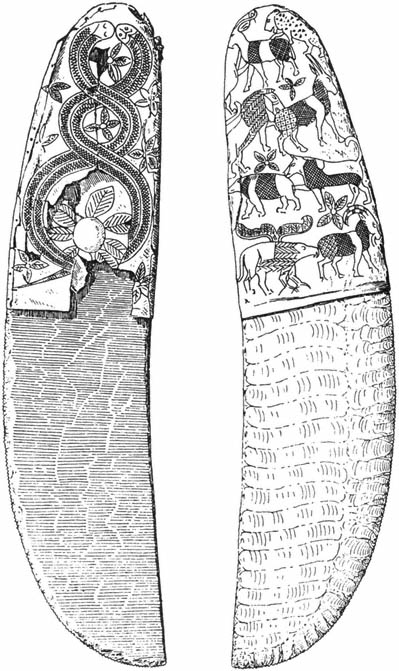

The carnivores and noncarnivores—potentially antagonistic species—are depicted in alternating rows on the knife handles and combs being examined here. They confront one another directly only in anomalous passages; for example, the artist of the Brooklyn handle (Fig. 8) closed a row of cattle with an attacking dog. What appears as an anomaly on the Brooklyn handle, however—a subsidiary intervention, literally on the edge of representation—can become the entire representation in full-scale depictions of the hunt. Presented on three decorated ivory knife handles (the Gebel el-Tarif, University College, and Berlin handles; Figs. 20–22), the carnivores and their prey are not associated with any elements except a plant-leaf rosette and, on the other side of the handle, intertwined serpents. With each beast and its prey alternating along a single baseline,[1] the plaiting together of the separate rows of the formula is analogous to the two intertwined serpents appearing on the side opposite the hunt scene, filling a long row along one edge of the handle; the intertwined serpents could even be said to indicate how the composition on the other side should be interpreted (see also the serpents below the elephant in the animal-row designs of Figs. 8, 9, 23, and 24). The most extensive of these three images, the Gebel el-Tarif knife handle (Fig. 20), depicts a lioness or spotted leopard attacking an antelope or deer, a lion attacking an oryx, a wild dog(?) attacking a wild boar(?), and a winged griffin attacking an ibex or goat(?) (Vandier 1952: 548–49) in alternating left-facing and right-facing bands.

The Carnarvon knife handle (Fig. 23), more sophisticated and also more innovative than these works, follows the same process of arriving at the order they exhibit but simultaneously revises it. In this respect it is the corollary—at the "beginning" of the chain of replications of late prehistoric representa-

tion—of the Narmer Palette (Fig. 38) at the "end." Both the Carnarvon handle and the Narmer Palette refashion a symbolic image by substantially revising, combining, and suppressing elements of an earlier metaphorics—in the case of the Carnarvon handle, the animal-row and the animal-hunt designs on works like the Brooklyn and Gebel el-Tarif handles, and in the case of the Narmer Palette, the very narrative image the Carnarvon handle begins to develop. Both the Carnarvon handle and the Narmer Palette exhibit the discomposure, the greater or lesser illegibility in terms of established pictorial textuality, that attends radical revision.

On the Carnarvon handle it is not clear whether the animal-rows pattern (from the Brooklyn and Pitt-Rivers or similar knife handles) derives from the carnivores-and-prey motif (from the Gebel el-Tarif or similar knife handles) or vice versa, or whether, more likely, both formulas subsist together as related, dependent terms embedded in a larger scene.[2] We can easily follow the maker plotting the image. He first laid out the row of storks at the top of the flat side, beginning with the well-established giraffe-and-stork motif from the animal-rows formula. That side of the image finishes, in the bottom row, with the lion following a group of bull oxen. Since the lion is not as bulky as the bull oxen, and since its tail follows the curving edge of the handle, it fits into the row as an anomaly, precisely to preserve the uninterrupted continuousness of the depiction of plenitude on this side of the image. The lion is dropped down a row from its "natural" place in the row of lions, where a lion is "pushed out" of its expected row by the elephant-and-snakes motif used to open it.

Next the maker flipped the handle over to lay out the top row on the boss side, beginning with the lion(?) (Churcher [1984: 168] incorrectly identifies a bovid) pursued by a dog that is overlapped slightly by a following hartebeest. This array violates both the identical-animal-rows formula and the carnivore-following-prey formula as well as the previously allowable revisions and supplementations to these formulas, the insertion of a single anomaly at an edge or side to preserve the uninterrupted continuousness of the formulas. Thus instead of continuing and extending the formulas and their revisions, the boss side of the Carnarvon handle escapes them altogether. More exactly, the top row on this side is a complete synthesis and revision of the entire flat side.

Fig. 20.

Gebel el-Tarif handle: ivory knife handle (covered in embossed gold leaf) and flint blade,

said to be from Gebel el-Tarif (el-Amra), late predynastic (probably Nagada IIc/d).

Cairo Museum. From Quibell 1905.

Fig. 21.

University College handle: carved ivory knife handle and flint blade, late predynastic (probably Nagada III).

Courtesy Petrie Museum, University College, London.

Fig. 22.

Berlin handle: carved ivory knife handle, late predynastic

(probably Nagada III).

Egyptian Museum, Berlin.

From Asselberghs 1961.

Fig. 23.

Carnarvon handle: carved ivory knife handle, late predynastic (Nagada III).

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (ex-collection Lord Carnarvon).

From Bénédite 1918.

It is not surprising, then, that the remainder of the boss side seems to "degenerate" (Bénédite 1918: 235) from presenting rows of animals to spreading out a complex composition legible only by taking the relative orientations of individual figures to give a "plan" or bird's-eye view of the action. According to this perspective, the image shows a dog pursuing a lion(?); a dog, at the edge, pursuing a hartebeest; and what may be two wild deer (center) and an oryx (bottom left) pursued by felines (leopards?). A rosette adorns the boss itself. (Churcher [1984: 168] identifies the two deer, has the oryx followed by a cow[?], and interprets the degraded bottom figures as antelopes[?], an even more anomalous grouping than the one I propose here.) The last figures to be worked into the image were evidently the leopard(?) at the bottom right edge, shown turning its head back toward the right-hand deer, and the dog, filling up the space on the outside curve of the edge and positioned at a right angle to the neat rows on the flat side of the handle. At least one pursuer, the right-hand leopard(?), does not face or follow but rather turns back to look at its prey, a device replicated and greatly elaborated in later works in the chain of replications; and at least one prey, the left-hand deer, seems not to be pursued at all.[3] Although the scene may depict beasts of prey and their victims, they are not literally shown as hunting. More exactly, the representation of hunting depicts not the attack or blow itself but rather the entire scene of sighting the enemy and masking the agent of the blow, the preconditions of the blow itself.

On the Carnarvon handle the edge is a place of "wildness," where representation enters the scene of nature obliquely and where the artist and the viewer are most directly represented in it. Here the wild dog who disturbed the serene plenitude of the Brooklyn knife handle is the only figure who can be fully seen in the image when the hunter who owns the knife actually picks it up and wraps his hand around the handle. Thus the wild dog stands for the human hunter in relation to the scene of nature to which the hunter is oriented at right angles. When the knife is used to wield the blow, the dog plunges forward just ahead of the hunter's real force. (If we were to accept these objects as having a "magical" status, then the dog could be said to be a magical guide or reinforcement of the hunter's action.) The dog is therefore the mask of the hunter's blow; the hunter stands and his blow takes "outside" the depiction per se. This and

similar if more complex devices in other works constitute the fundamental pictorial mechanics and metaphorics of the late prehistoric Egyptian scene of representation.

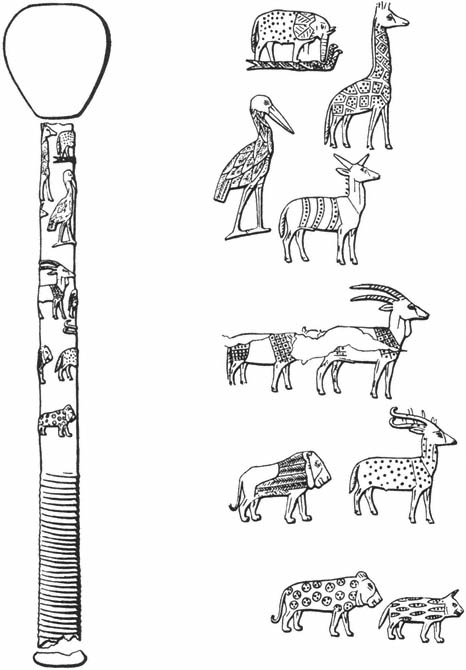

With different compositions on its two sides, the Carnarvon handle suggests that the animal-row images and the animal-hunt images on works like the Brooklyn and Gebel el-Tarif handles were apparently viewed as distinguishable from one another but nonetheless to be juxtaposed—although perhaps only in a revisionary repetition—as related terms. The maker of the Carnarvon handle evidently set out to bring animal-rows and carnivores—pursuing-prey motifs into formal alignment and therefore, presumably, into some kind of metaphorical association. A decorated scepter or mace handle from Seyala in upper Nubia (Fig. 24), probably roughly contemporary with the Carnarvon handle (Kantor 1944: 129–30; Williams 1988a: 4–5), exhibits an identical structure worked out in a somewhat different physical format. Although not presenting two sides of an artifact to be turned over in the hand or flipped, the pictorial text is clearly divided from top to bottom on an object that can be rotated around itself. At the top of the scepter two groups of animals replicate—derive from and present compactly—the animal-rows formula. One element of the formula, the rows of various animals, is the stork and antelope; the other, the specific "groupings" of animals, is the elephant-on-snakes motif plus giraffe. At the bottom of the scepter three groups of animals replicate the carnivores-and-prey or animal-hunt formula, a lioness(?) pursuing an oryx, a lion pursuing a stag, and a leopard(?) pursuing a hyena(?). But as on the Carnarvon handle, the distinction between the two formulas, in its very repetition and reduction to a synthesis, is to some degree broken down. The five groups of animals cannot be divided into two equivalent classes, one for the animal-rows formula and the other for the carnivores-pursuing-prey formula.

In light of what we discover about the metaphorics of the lioness and/or lion in images like the Hunter's and Battlefield Palettes (Figs. 28, 33), it is significant that the figures of this creature, in the middle row and the following fourth row of the Seyala scepter and on the Carnarvon handle at the "end" of the flat side and the "beginning" of the boss side, carry or provoke the elision and revision in the presentation of the two formulas. Later replications of the

Fig. 24.

Embossed gold mace handle from Seyala, Nubia, late predynastic (Nagada III?).

From Kantor 1944 by permission of the author.

lion figure may refer retrospectively to these prospective revisions in which the power and danger of the beast has been increasingly represented in its central, albeit discomposing, place within the scene of nature's plenitude. It will not be surprising if the figure of the lions comes ultimately to represent the person of the human ruler. The dog has a similar general status as a wild figure, an anomaly within the formal order of the formulas that allows them both to be sustained and to be revised and reduced. Later revisions of the representation of the wild dog—as they return retrospectively to these images—will give it an increasingly literal position as the "frame" of the depicted scene, as on the Oxford Palette, where two wild dogs are placed like heraldic emblems at the top and surrounding part of the image (Fig. 26).

The significance of' lion and wild dog in the images on the Brooklyn or Carnarvon handles and the Seyala scepter cannot be the same as in later images, where we discover that the beasts function somewhat differently in each succeeding replication. But it is fair to say that on the Carnarvon handle both animals are nodes on which the pictorial mechanics literally turn as well as sites of strong metaphorical activity. Although such symbolic or metaphorical meanings are probably irretrievable, the beasts of prey might stand for the human hunter, who actually uses the knife in killing, carving, skinning, or sacrificing the hunted animals. The human hunter is not literally in the depicted scene, but he figures at its edges and surrounds or encloses it on all sides and outside the frame. It is he who sees the entire scene, turns the object over on itself in "following" the lion through the image, and then wraps his hand around this folded-over image to see only the wild dog just ahead of him plunging at its prey. The prey hunted by the dog within the depicted scene is not necessarily the same as the prey hunted by the hunter outside the depicted scene, which that depiction represents. As will become clear, the viewer can be the prey. In the same way the hunter is masked from the identities depicted within the scene by the dog who represents him, the entire image masks the hunter from the viewer, for if the viewer is viewing the scene, the knife is not being gripped—that is, the hunter is not hunting. At most the viewer sees the depicted scene only in the moments immediately before or immediately after the hunter strikes his decisive blow. The blow itself is always outside the depiction, if nonetheless the condition of and for the scene of representation.