One of Makibuse's Poor Peasants: 1719-1744

Ken was a native of Makibuse, the daughter of a peasant named Rihei, whom we shall refer to as Rihei II since her grandfather bore the same name (hence we will call the grandfather Rihei I). Born in 1719, she was forty-four at the time of the registration incident. Her mother was from Yawata village, a station on the Nakasendo[*] two and a half kilometers east of Makibuse (the last station in the Kita-Saku plateau before the highway winds its way westward into the mountains to the next station, Mochizuki, where Ken's husband had come from); Makibuse's northern border also touched the Nakasendo[*] . In 1694, at the age of sixteen, slightly earlier, perhaps, than was usual for girls, Ken's mother had married Rihei II.[17] She bore him a son, Shinzo[*] , in 1700; a daughter, Ine, twelve years later; and finally Ken, her last child, seven years after that, in 1719.

Ken's father died the year she was born. By then Shinzo[*] was nineteen, old enough to work the fields, and Ine, seven, could help care for her baby sister. At age fifteen, rather young, Ine married out to Yawata, where her mother (and paternal grandmother)[18] were from, perhaps to reduce the number of mouths to be fed in the family.[19] Ken's first

[16] See the discussion of this issue in chapter 3.

[17] Ichikawa Yuichiro[*] (Saku chiho[*] , 113) found that the average marriage age in the area was twenty-three to twenty-four for men and sixteen to seventeen for women. These are a couple of years lower than Hayami's findings for another district in Nagano or Smith's findings in his study of Nakahara (Hayami Akira and Nobuko Uchida, "Size of Household in a Japanese County throughout the Tokugawa Era," in Household and Family m Past Time , ed. Peter Laslett [Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1972], 502; Thomas C. Smith, Nakahara: Family Farming and Population in a Japanese Village, 1717-1830 [Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1977], 94-96).

[18] See the sixth entry in the 1671 population register of Makibuse, in NAK-KS2 (1): 771.

[19] Smith (Nakahara , 93-95) found that daughters of wealthier families married considerably younger than those of poor families. He suggests that this may have to do with the fact that the poor spent time as servants to supplement family income. In other circumstances, however, early marriage of daughters may have been a solution to the problem of too many mouths to feed.

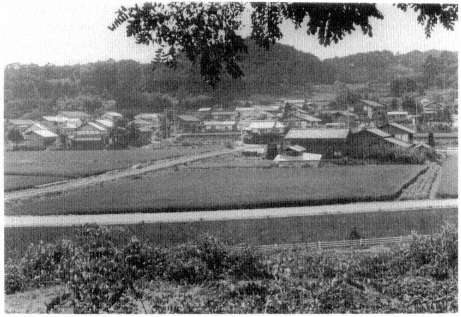

Plate 1.

Makibuse Village. Facing west toward Mochizuki, some three hundred

meters south of the Nakasendo[*] . Photograph by author.

marriage, in 1737 at age eighteen, brought her to Mimayose, two kilometers beyond Yawata on the Nakasendo[*] , leaving her mother and unmarried brother in Makibuse.

Shinzo's[*] bachelor status at age thirty-seven needs some comment, although a specific psychological or other personal explanation is not available. Perhaps he had been married and was divorced; we do not know. The thought that he might have been an unattractive prospect seems culturally incongruent. Males must have had the strategic advantage in a society like that of Tokugawa Japan. It is possible that Shinzo[*] could not afford a wife, that the reason of his bachelorhood was sociostructural rather than personal. In 1671, at least, the only bachelors of marriageable age in the village were indentured ser-

vants.[20] A socioeconomic explanation would thus point to the near-poverty situation of the family, although even "landless," that is, tenant, peasants did marry, as did Ken.[21]

Outmarriage was quite common in Kita-Saku district from fairly early in the Tokugawa period, contrary to Smith's assumption of a "village rule of endogamy except for high-placed families who had to go outside the village to find marriage partners of comparable family rank."[22] The 1671 population register of Makibuse recorded thirty-two peasant households (including fourteen titled peasants), all but two headed by couples (see table 1). In addition, there were seven married sons, brothers, and nephews of titled peasants co-residing with their main families in an extended-family pattern, which makes a total of thirty-seven couples. Only seven of the thirty-seven wives were from Makibuse; all the others had inmarried from villages in the same district or, in one case, from another district. Yawata tops the list of villages as sources for wives, with five. As for outmarriage, fourteen daughters or sisters of current household heads married out. Only two Makibuse women married out to the Kita-Saku plain; the rest settled in the mountain area. On the other hand, ten wives came from the plain. All twenty-three bond servants (genin and fudai ) came from the mountain area, from within a radius of eight kilometers.

Thus, the number of women marrying within the village (seven) was

[20] According to the population register of 1671, none of the bond servants (genin and fudai) were married. There were nineteen indentured servants (genin) in Makibuse—twelve males ranging in age from thirteen to thirty-four and seven females between fourteen and twenty-three—and four lifetime servants (fudai) between the ages of nine and twenty-two (see NAK-KS2 [1]: 771-80).

[21] Smith (Nakahara , 92) found that the probability of male celibacy in lower-class peasant families (those with holdings of less than four koku) was from two to ten times as high as that among wealthier peasants (67 percent for the cohort aged thirty to thirty-four and 41 percent for those aged thirty-five to forty-nine). Pierre Bourdieu discusses the structural necessity of bachelorhood of nonsuccessor males for reproducing the social system in the late nineteenth century m the Béarn in southern France in "Célibat et condition paysanne," Études rurales , nos. 5-6 (1962): 32-135.

[22] Thomas C. Smith, The Agrarian Origins of Modern Japan (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1959), 61, 62-63 n. 1. My occasional critique of this excellent study should be understood in light of the vast amount of Japanese scholarship produced in the last thirty years. In Nakahara (133-34, 143) Smith reports only that "nearly all daughters were married our of the family" but gives no figures for out-village marriage. See also the following note.

Table 1. | ||||||||||||

Population | Households | |||||||||||

Male (genin ) | Female (genin ) | Total | Horses | Honbyakusho[*] | Kakae | Mizunomi | Total | [Kokudaka ] | ||||

1671 | 73 (13) | 60 (10) | 133 | — | 14 | 18 | 0 | 32 | [175] | |||

1700 | 93 (18) | 80 (10) | 173 | — | 16 | 24 | 0 | 40 | ||||

1717 | 121 (12) | 104 (10) | 225 | 18 | 13 | 30 | 4 | 47 | [205] | |||

1725 | 129 (14) | 99 (11) | 228 | 16 | 12 | 33 | 3 | 48 | ||||

1737 | 136 (15) | 112 (9) | 248 | 16 | 12 | 38 | 2 | 52 | ||||

1750 | 130 (11) | 112 (9) | 242 | 12 | 11 | 35 | 2 | 48 | [205] | |||

1764 | 129 (11) | 115 (9) | 244 | 10 | 11 | 43 | 3 | 57 | ||||

SOURCES : Adapted from Ozaki, "Kenjo oboegaki," table 9 (p. 97); the population for 1671 is from NAK-KS2 (1): 771-81, and the kokudaka is from NAK-KS2 (2), appendix p. 53. | ||||||||||||

NOTE : Land development seems to have reached its capacity in the late seventeenth century. The kokudaka of 205 was first recorded in 1704 (NAK-KS2 [1]: 613); between 1704 and 1834 another 16 koku were added. | ||||||||||||

only half of that marrying out, and this in a community where thirty-seven wives were needed for households to reproduce. If one adds all marital liaisons in and out of the village, the total is fifty-one, out of which only seven, or 14 percent, were endogamous to the village.[23] This contrasts sharply with 50 percent and 75 percent for other villages in the area (Komiyayama in 1669 and Wada in 1713, respectively), as Ichikawa Yuichiro[*] relates.[24] He also concludes that the average marriage age in the district was twenty-three to twenty-four for men and sixteen to seventeen for women, and he notes that almost all of the indentured servants (genin) and lifetime servants (fudai) were unmarried.[25] In 1671 none of Makibuse's nineteen genin or four fudai were married.[26]

Let us return to the narrative. In 1742, five years after her first marriage, Ken's name reappears on Makibuse's family register, which means that she had left Mimayose and her husband, although it is unknown whether this was a divorce. The household she returned to, however,

[23] Finding a wife appropriate to one's economic status, which might necessitate liaisons outside the village, does not seem to have been a motive either. After the 1670s the overwhelming majority of the peasants in Makibuse were very small landholders. The seven marriages within Makibuse that were recorded on the 1671 population register were as follows (honbyakusho[*] means "tired peasant"; kakae refers to a branch house in a lineage):

1. Headman (29 koku) and daughter of honbyakusho[*] (5 koku; 21 koku before partition)

2. Honbyakusho's[*] son (6) and kakae (4) daughter

3. Kakae (2) and kakae (5) daughter

4. Kakae (2) and kakae (5) daughter

5. Honbyakusho[*] (5; 23 before partition) and kakae (5) daughter

6. Kakae (5) and honbyakusho[*] (7) daughter

7. Honbyakusho[*] (7) and kakae (10) daughter

[24] Ichikawa Yuichiro[*] , Saku chiho[*] , 83. On the other hand, Makibuse's geographic distribution of spousal provenance is very similar to that of Kodaira (a village studied in more detail in chapter 3), some four kilometers to the east. The latter's population register of 1694 lists fifty-four couples, in only six of which both partners had been born in Kodaira; in the other forty-eight, one spouse, usually the wife, came from within a radius of twelve kilometers, thirty-six from within a radius of four kilometers (see Komonjo kenkyukai[*] dai ni han, "Genroku-ki no shumon[*] aratamecho[*] o miru," Mochizuki no chomin[*]no rekishi 12 [1988]: 64-65).

[25] Ichikawa Yuichiro[*] , Saku chiho[*] , 110, 113.

[26] See n. 20. For comparative data on lifetime servants and indentured servants in the area, see ibid., 108, 120 ff.

consisted now only of herself and her mother. Shinzo's[*] name had disappeared from the register. The possible reasons for such disappearance are limited to a few: death, outmarriage to another locale (temporary employment elsewhere would be duly recorded and not cause removal of the name), petition by relatives and kumi members for reasons of disinheritance (kando[*] or kyuri[*] ), or abscondence to an unknown destination. The authorities kept a close tab on the whereabouts of all subjects.

The previous year's register offers no clue about Shinzo's[*] fate. Ken's return, however, may have been prompted by the need to take care of her mother, then sixty-four years old (or seventy, according to the entry of that year), and the minuscule plot of land (0.19 koku, the equivalent of 2 ares or 0.04 acres, of medium-quality dry fields) for which her mother was responsible in the village. Or was this a pretext to get out of a marriage that was not working? Ken was left completely alone when her mother died in 1744, two years after her brother's disappearance. She was then twenty-five.

The death of her mother brought a change in Ken's "civic" status, as we know from the next year's entry. Until then the household had been registered as a kakae , or branch family, of her uncle Gendayu[*] , her deceased father's younger brother. Kakae literally means "embrace" or "hold in one's arms" and refers to the client-patron relationship of dependency between branch and main houses; the term will be rendered hereafter as "branch house," "fully established branch house," or simply "client." Now she was legally incorporated into her uncle's household and entered under his name (she was thus chonai[*] , or "on [his] register," that is, co-resident), although it is unclear whether she actually moved into his house, since she had one of her own.

In order to grasp the significance of this change, one needs to understand the highly structured village social and political hierarchy. First, there was the great divide between peasants and nonpeasants, perhaps as great as the divide between rulers and ruled in the society at large. The nonpeasant population increased throughout the Tokugawa period as craftsmen, doctors, and others took up residence in the countryside in increasing numbers.[27] But these nonpeasants were marked in the registers as belonging to an inferior class: all of them were registered as clients or bond servants (genin).[28]

[27] For Saku district, see ibid., I44-46.

[28] Ibid., 128.

The first article in the village laws, including Makibuse's, reveals this hierarchy in the context of certifying that no Christians were present in the village: "Art. 1. Re: Christians. Following the investigations of the past, each and every one, down to the last person, has been thoroughly examined: not only (moshioyobazu[*] ) house owners [but also] men, women, children, servants and semi-independent branch houses (kadoya ), renters, fully established branch houses (kakae), down to (sono ta ... itaru made ) Buddhist monks, Shinto priests, mountain priests (yamabushi ), ascetics, mendicant monks with flutes or bells, out-castes, common beggars and registered beggars (hinin , "nonhumans"), etc...." (see appendix 3). This comprehensive list is clearly hierarchized; none of these undesirables seem to have resided in Makibuse.

Nonpeasants were second-class citizens within the village, yet some peasants also fell into this category. At the bottom were mizunomi-byakusho[*] , literally, "water-drinking peasants," without land of their own, pure tenants whose number increased over time. Next were non-titled landholders, who, although they were autonomous proprietors, were incorporated into a political dependency relationship as real or fictitious fully established branch houses (kakae) to main families, lineage heads, or patrons (kakaeoya ). Thus were constituted lineages and sublineages, crisscrossing or overlapping the kumi (as in Makibuse). All landowning peasants, even immigrants, belonged to a "lineage." Prior to Ken's mother's death, her household was a kakae under her uncle Gendayu[*] .

The titled peasants (honbyakusho[*] ) constituted the village council, and all lineage heads were titled peasants. In the eyes of overlords, they were the official tribute deliverers. The two categories of landowning peasants—fully established branch houses and lineage heads—often had a number of dependents: lifetime (fudai) and indentured (genin) servants, semi-established branch families living in a separate dwelling on the premises (kadoya), renters, and dependent co-resident members, like Ken after her mother's death.

This multilayered class, status, and social hierarchy, which allowed for some controlled mobility (specified later for Makibuse), was thus from the bottom up: nonpeasants, lifetime servants, indentured servants, co-residents, pure tenants, semi-established branch houses, fully established branch houses, titled peasants (who allowed for further power combinations with the suprahousehold authority positions of lineage head, kumi head, and headman).

In 1721 Makibuse counted thirteen titled peasants (the same number as in 1647 but three fewer than in 1700 [see table 4]) and thirty-six others, among whom were four landless peasants who first appear on the rosters around 1710 (see table 1). In 1721, moreover, of the forty-five landholding peasants sixteen had holdings of less than 1 koku, eighteen had between x and 4 koku, and eleven had 5 or more koku. Ken's household was among the poorest in Makibuse. With its 0.19 koku, it was dangerously close to landless status. Ken was not a titled peasant, and her shift in status from fully established branch house (kakae) to co-resident (chonai[*] ) meant the loss of an already very circumscribed control over her own life.