IV

Lust

Lust was written in Bangkok in 1990.

The Calypso. It's the biggest theater on Thanon Sukumvit, Bangkok's Fifth Avenue. It has seats for two thousand; expensive seats for the well-heeled and upwardly mobile: Germans and Japanese and Americans and French and Saudis and Kuwaitis and Chinese from Hong Kong and Singapore. There is a cast of a hundred, a different show each night. Palaces, skyscrapers, desert oases drop upon the huge stage in outbursts of electric lightning. The Empress of China appears, seated on the uplifted hands of muscular men whose naked bodies have been metallized in gold greasepaint. Gongs and the shakuhashi propel the advance of the traditionally transvestite dancer of Japanese Kabuki theater. Now the stage fills with ballerinas spinning out adagios and minuets from Swan Lake. Mahalia Jackson with rapturous voice sees the sweet chariot comin' to take me home. Mae West comes sashaying in with a chorus line of nuns. Marilyn Monroe resurrects with puckered lips to coo for diamonds; your incredulous fingers want to feel for the wound to be sure. Divas, grande dames, vamps, pop superstars, they are all, of course, men in their early twenties. Now there is the stripper. With rose-blushed complexion, under a sunny cascade of Farrah Fawcett hair, clad in a silver-sequined gown, she uncoils in the cone of a spotlight. She slinks toward you on spike heels, her lips tremble and part, her sultry eyes fix you, her silvered fingernails clutch

at her sides, grip her breasts, slide down between her thighs. She unbuckles her waist-sheath with convulsive movements, flings off her skirt. You slide into the movement: props and plumage being shed to reveal flesh and nature. But at each stage of the strip the more is exposed of her body the more female she gets! Your mind is getting twisted behind your eyes by the contradiction between the ample thighs, soft belly, full breasts your prurient eyes see and what you know. Her eyes are pulling at you with torrid magnetism. Finally she snaps off the cache-sexe: you see pubic hair, mons veneris. How the hell could she gyrate like that with her cock somehow pulled between her thighs? Then abruptly, for just a second, the cock flips out and the spotlight goes off and she is gone.

This now must be the last number. A big iron cage is wheeled out by an stout matron in safari garb and wielding a whip. Inside the cage, a dozen extravagantly beautiful women. There is a Thai in Siamese courtesan costume, an Indian in a sari, an Indonesian in a sarong, a Filipina in a terno , a Vietnamese in an ao dai , a Cambodian in a sampot. They are clinging to the bars of the cage, shivering with fear and weeping. On the right side of the stage there is a gathering of men, German and Japanese and American and French and Saudi and Kuwaiti and Chinese from Hong Kong and Singapore. The matron in the safari drag unlocks the cage and brings out the women one by one for inspection. One by one, each man makes his selection and leaves, until the cage and the stage are empty.

After some moments the audience applauds briefly. Then they file out, looking at the floor, past the performers who are lined up in the lobby, their hands folded in the traditional wai greeting.

Antifeminist theater: transvestites are more sensual, more charming, more tantalizing, more seductive than one has ever seen debutantes, fashion models, starlets, or British princesses. They are the ones who have cut through all the inhibitions to realize the consummate feminine look, that—Baudelaire said—blasé look, that bored look, that vaporous look, that impudent look, that cold look, that look of looking inward, that dominating look, that voluptuous look, that wicked look, that sick look, that catlike look, infantilism, nonchalance, and malice compounded.[1]

They always let you know. Something shows through—the lean flanks, the curves only drawn in by posturing, the unmuscled but overset shoulders: the body underneath not female though not masculine, virile, either. They lip-synch to perfection songs of a dozen languages they do not know, but you do see that it is not these Adam's-appled throats that are trilling these soprano songs. If the performer has finally had so much plastic surgery done and is so artfully costumed that you no longer see the squarish shoulders or the pelvis too narrow for maternity, then the magic is gone and there is just an ordinary female singer imitating an act another woman created. These are not males pathetically trying to look and act like women; they try harder than women, dare more, outdo women. These twenty-year-old guys emanating, delighting in, flaunting one-night-stand sexual identities which we in the audience have known as destinies and obligations.

You, who came dressed up or dressed down for the show, feel your femaleness being discredited in this gala of divas and superstars. You, her husband or her date, or just there with the guys, feel something aggressive against you in all this glamour and gaiety,

which you, after showering and shaving, would never try to concoct.

One hardly ever notices transvestism in the streets in Bangkok; the cabaret is its space. Space not for the discontent of nature, but for the specific pleasure of theater. We foreigners, gaping at the female voluptuousness affected by these male performers, don't get a lot of what is going on, especially when the numbers are Indochinese female impersonations with Indochinese songs. The cabarets of Bangkok compete in sumptuous costuming and dazzling stage effects; the performers, superlative dancers and poseurs, virtuosos of an enormous range of moods and expressions, queens in realms of colored floodlights and canned music, affect more glorious and hilarious female wiles than one had realized Thai culture had created and foreign cultures exported. When I left Bangkok for Paris, I went to see the shows in the Alcazar and the Madame Arthur and found them really uninventive by comparison.

There is the specific pleasure of transvestite theater. There is no script for which a director seeks actors who are naturals for the part. They don't do plays, stories; they just do the femme fatale, the czarina, the college cheerleader, the Brooklyn Jewish mother, each the matrix of an indefinite number of plots and intrigues. They have no director, no one is a natural for a role, each one inverts and transposes his nature entirely into a representation. Each is a parthenogenesis in his own laser-beam placenta.

Primal theater that recommences today in Harlem discos and rock concerts rediscovers transvestism. It is only bourgeois theater, which the Balinese think is not theater and Artaud dismissed as recited novels and pop psychagogy, that is not transvestite. The female roles of Elizabethan theater were played by

boys. In this theater of the greatest and most single-minded age of English imperialism, these boys were parodies of imperial males. The Queen found much of Shakespeare to her distaste. In Japanese Nô theater, the high theater of the samurai caste which glorifies their Zen ideals, all the roles are played by mature men. Kabuki, the low theater of the merchant class, originated in the red-light district of Kyoto and its plots parody the plots of Nô theater. Female prostitutes played all the roles; Kabuki was performed as an entertainment for male merchants. But it happened that Kabuki was so rich in theatrical innovations that it attracted clandestine visits from the samurai, who soon appropriated it, upgraded it, composed music and text for it, and it too came to be performed entirely by male actors. The T'ai people are profoundly matriarchal, and rural Thailand, Laos, and parts of Myanmar are to this day. Patriarchal culture entered Siam late, through the royal family, which, though to this day Buddhist, in the late Sukhothai period—as Angkor long before it—imported brahminical priests and, with them, Vedic patriarchal culture. Under King Chulalongkorn's program of modernization, large numbers of Chinese coolies were imported to build the land transportation system across this river kingdom; these were to stay on and settle into the traditional commercial activities of Chinese everywhere in the cities of South Asia; today a third of Bangkok is Chinese. They are the second entry of patriarchal culture into Siam. Since the Sukhothai period, in the now patriarchal court of the king, all the roles in the high court theater of Siam have been performed by women; it was conceived as an entertainment for the king. Village culture centered in the temple compounds, the wats , which are regularly the scene of

religious feasts and fairs. There popular theater developed—entertainment featuring rogues and outlaws, burlesquing, as low theater everywhere, the manners and heroic legends of the court. And working in, under cover of comedy, ridicule of state policy and even of the monks. Low theater inverts and parodies high theater. The popular theater of matriarchal plebeian Siam put males in and out of all the roles.

In the cabarets of Bangkok today this theater has been reoriented for an international audience. Even in the cheap cabarets full of Thais, the farang tourist has the impression that the show is being performed for him. Although every show contains some acts from Siamese popular theater, in the sound systems, the disco music, the media superstars being impersonated, the cabaret is very Western and Hong Kong-Singapore-Tokyo. This occurred recently, when the military junta put in by the Americans during the Vietnam War realized that the planeloads of dollars that came into the country with the tens of thousands of GIs on R'n'R in Bangkok and Pattaya could be kept coming by maintaining Thailand as the R'n'R place for businessmen and professionals; today 82 percent of the tourists are unaccompanied males. After the Vietcong victory, the junta in Thailand liquidated the socialist and separatist guerrillas in its territory by itself, by decreeing economic enticements to foreign industrial investors, deemphasizing agriculture, and guaranteeing a cheap labor pool (the bases for the Asian Tiger economy that Thailand became in one generation), but also by conscripting the young men in its own army and the young women from the undeveloped provinces into the Bangkok and Pattaya sex resorts.

Those who go to the performances of Siamese classical dance the Ministry of Tourism puts on at the

National Theater don't want to be tourists on the make, more ugly Americans in post-Vietnam War Southeast Asia. You're on R'n'R, but you're not a GI. What you want, here in Bangkok, is not some meat to get off on, you want Miss Thailand. In the sex resorts, they do not just line the street with naked young women and men; they put on the beauty contests, in which Miss Thailand wins the international one year. To tell the truth, the lay will not be very good; the bodies are too mismatched, and in the end you will do a kind of pathetic reciprocal masturbation in the dark. So they provide the cabarets with the real women, the Onassis and Donald Trump kind of gal, performing for the credit-card troops, who frankly can't relate too well to those little Siamese dolls swarming around the barstools. Mae West, Tina Turner, Margaux Hemingway, or Margaret Thatcher come join you at your table between acts.

You are sitting there, digging the show they are putting on for you, a little abashed at how far they are willing to go to be sex objects for you, to the point of changing their sex, to the point of themselves glorying in being the latest kind of corporate-produced media siren. Yet the cheaper places full of Thais who have paid to get in have the same kind of shows. They all seem to be honored to stand in the dark and watch the high theater created for the entertainment of the white kings. A high theater they have inverted: the voluptuous entertainers are men. Might it not be for the Thais around you low theater, travesty of the manners and intrigues and even of the state policy of the white court? In old Siam the kings used to go in disguise to the fairs in the village wats; the players had to learn to cover well their ridicule with entertainment. In Bangkok the white kings are

welcomed by the ruling junta—they pay. The ambiguity of low theater has to be yet more elusive.

You do feel uneasy in those places. They make it look so easy, to be a white superstar, these twenty-year-old farm boys from the rocky Himalayan foothills of the Isaan who just got to Bangkok last year. The added gender confusion they put into the creations that Michael Jackson, Madonna, and Grace Jones have made of themselves. And that number where a Thai man turns into a very female, pansy, body, to do a Thai woman doing impersonations, for your AC-DC excitement, of Rock Hudson, Tom Cruise, or John Travolta.

"You there, from Cincinnati, you from Frankfurt, you haven't seen half these your women back home; here in Bangkok you can see them all in a single night. Oh come on, we're all bisexual; you really would dig a blow job from a Thai boy wouldn't you, only 500 baht? What's that? You say, frankly you would from a Greek sailor, but Thai men, well, are just not your type? Okay, just give me a half-hour. . . . Now how do I look to you? Madonna! We're men, of course, but you did not come here to watch the conscripts on parade, did you?"

"Oh love, how beautiful you are, how I wish I could trade noses with you, is your handbag a real Gucci? Sister love is the real thing—are you staying at the Oriental?"

They do try to put you at your ease, these charmers chatting with you so ingratiatingly at intermission, greeting you by name, like your friends already, in the lobby after the show. Yet you leave without one of them. They have made you feel inferior, sexually inferior, not as daring, not as attractive. The next night you and your sisters head for a singles bar, advertised in the Tourism Ministry brochure, featuring

a go-go show of men. Thailand is a matriarchal Garden of Eden. The owner, welcoming you at the door, is an aged queen. The show consists of youths dancing desultorily to Western pop music who occasionally strip of their G-strings. They, you discover, hardly speak any English—selected for their looks from among laborers trucked in from the provinces to work in construction gangs in Bangkok. Men without the apparatus of virility. You notice that most of the other clients are gay men.

The next night you go to one of the massage parlors, where there are a hundred straightforward country girls, seated in banked rows behind a one-way plate-glass window with numbers on their bosoms; you can pick one and she will massage, blow, and spread for you. But they have spoiled it for you, on the stage at the Calypso, with their last number with the cage and the matron with the safari suit. The one you picked stroking the baby oil now on your thighs is just a farm girl from the Isaan in Bangkok to put her kid brothers and sisters through school. You think of the glamorous ones, of the Calypso stage; you toy with the idea of going back and taking one of them to your room, taking up the challenge. Taking one of these guys that dares everything back to your room, and seeing what would happen, between two more or less bisexual guys stripping for one another.

Back in the company lounge, when you are asked about your trip to the notorious Bangkok, what you will tell is not about the clumsy peasant girls lined up by the hundreds waiting for somebody to fuck them for a few bucks. You will tell about having Miss Thailand in your room for a night; you will tell about the Calypso—in the classicalized genre of the narrative: "There she was, at the bar, the most gorgeous

thing you ever saw, huge boobs, et cetera . . . and then when we got back to the room at the Oriental and I got her dress off, I couldn't believe my eyes, imagine my disgust!"

It's the show in the world's biggest sex resort, but you are not sitting there with a newspaper over your lap. The libido in this libertine theater is not a matter of nerves going soft, postures caving in, lungs heaving, sweat pouring, vaginal and penile discharges. The theater of sex is a theater of representation. A woman in Port Arthur, Texas, with her voice, her movements, her own concupiscence, had the spunk to create a number; it is transported whole to the other side of the planet; she factors out; her very physical nature of being a female factors out. It is the representation of the self that carries the erotic charge. But the performer—this male Thai—is there, and shows through, and is now blended into the act to heighten its brazen glamour. What makes the number the more wanton and suggestive is that he is there as a representative male (his own masculine personality all covered over, his specific maleness factored out), and also as a Thai doing an American woman. It is not just the physiognomy, the swagger, the enfante terrible of the Vietnam-War-torn sixties Janis Joplin that is being represented; it is a Thai representing her that is being represented, representing inevitably with himself the position of low theater with respect to the ruling icons and effigies, representing economic and cultural subordination, representing a certain moment of geopolitical history—smelted into an erotic trope. You went for the charge, but to those who hold themselves to be serious cultural travelers and not gross tourists and who go to the performances of Siamese classical dance you now say:

if you really want to know about Thailand go to the cabarets!

It is the specifically erotic figure, and not the classical dancers, that has this representational power, because it implicates you. Not only because the cabaret show is also the presentation of the charms of the escorts all of whom are available to you to take back to your hotel, but because even while you are sitting there just watching the show you feel yourself being challenged to an intercontinental sexual duel. The decent theater is spectator theater; on the stage of the National Theater or in the restaurant of the Oriental Hotel, jeweled and masked courtesans pursue their dangerous liaisons, from which the decorous hands of time have disentangled the foreign voyeurs—as well as the ushers, the maitre d', the waitresses, and the performers themselves.

When you splash cologne over the greasy pores of your carnivorous body, take out the more rakish of your shirts from the suitcase, go and pay for the ticket, speaking English to the teller, your credit card, your shirt and your boutique-bought dress, and your suave and unflappable manners are so many props in the theater of libido. All your words are phallic or lambda symbols; if you mention the plane to Hong Kong you have to catch tomorrow, speak of the comfort of the Oriental Hotel, if you answer, when they ask, what company you work for, or what university, all this is so many tropes in the rhetoric of seduction.

The farm boys from the Isaan whose libido can be contained within the confines of village possibilities and constraints are in Bangkok for a few years working on construction gangs or in the sweatshops; it is those with excess sensuality who are working out in

gyms, in dance classes, grooming themselves, cultivating suggestive gestures, learning English, learning the rhetoric of seduction. This cabaret superstar is a representative of a backward Isaan economy whose only productive resources are bodies, the unreproductive bodies of the Bangkok sex theater; you are a representative of a productive economy that produces professionally qualified bodies, assets with which you acquire productive wealth. It could be that you are challenged by his provocations and feel a lascivious urge to take him up on it: After the show, in my hotel room Mr. Cincinnati and Miss Bangcock! Frau Frankfurt und Kuhn Butterfly!

The libido makes the self a representative. Libido is not nostalgia for, and pleasure in, carnal contact. One was a part of another body, one got born, weaned, castrated. The libido does not adhere to the present, but bounds toward the absent, the future; it extends an indefinite dimension of time. What makes this craving insatiable is the way back blocked: the way back to symbiotic immediate gratification. Libidinal impulses are not wants and hungers but insatiable compulsions, sallies of desire, which is desire for infinity, for Jacques Lacan's l'objet a. It is libidinous desire that stations the self in the Oedipal theater, in the polis, on the field of objectives which is the objective universe and which is the universe of objectives of desire, in the world market, in le symbolique.

If our libido is a part of ourselves, the libidinous gesture or move, reaching for the universe of desire, represents the whole self. Psychoanalytic pansexualism turns into a science of the subject.[2] And the self is a representative of le nom-du-père , the Oedipal theater, the reason and the law, the corporate state, the

cybernetic digital communication chains, the West. The libidinous gesture or move transacts with another, not for discharge into a set of carnal orifices, but for another libidinous gesture which is a representative of another self, a representative of another reason and law, transnational corporation, corporate state, continent. The love one knows is the gift from the other of what the other does not have.

One would have to read the libido, see it in its context, interpret it. Our phenomenology of sex is an interpretation of intentionalities, representatives, a decoding of barred objectives of desire, a transcription of dyadic oppositions, an inscription of différance. Tracking it down we end up, like Plato, finding the whole of culture—including its technology and its relationship with the material, the electromagnetic universe. Lately we have also been doing a machinics of libidinal bodies, a mechanic's analysis of what the parts are, the couplings, how they work, what they produce.[3] We find, with Ballard in Crash ,[4] our landscape of automobiles, high-rises, MIRV missiles, and computer banks very sexy, representative of our own libidinal machinery. We have also been doing, with Lyotard,[5] a microanalysis of freely mobile excitations, inductions and irradiations, and bound excitations, representing our erotogenic surface as an electromagnetic field. The I or the Ça (the Id) that is aroused in the Calypso is a representative of le nom-du-père , of the phallus, of the text of culture, the technological industry, the electromagnetic universe. Intelligent talk about sexual transactions among us is talk about transactions with representatives of the self.

But on stage at the Calypso you caught sight of something else—the body underneath not female and not

virile either, the pelvis too narrow to harbor a fetus, the lean and unmuscled thighs, the still adolescent shoulders: the indeterminate carnality. You remember passing by this young guy in jeans and sneakers heading for the backstage entrance. That body, now slippery with greasepaint and sweat, belly cicatrized from the tight plastic belt, feet raw in the spike heels, troubles you. He came from a rice paddy in the Isaan, you came from a farm in Illinois, a working-class apartment in Cincinnati. If one could somehow join, immerse oneself in the physical substance of that body, one would have a feel for the weight and the buoyancy, the swish and the streaming, the smell and the incandescence of the costumes, masks, castes, classes, cultures, nations, economies, continents that would be very different from understanding the signs, emblems, allusions, references, implications. Something in you would like to know how it feels to be that bare mass of indeterminate carnality being stuck in spike heels, sheathed in metallized dress, strapped to a crackling fiberglass wig, become phosphorescent in a pool of blazing light. Something which is the stirrings of lust.

Lust does not know what it is. The mouth lets go of the chain of its sentences, rambles, giggles, the tongue spreads its wet out over the lips. The hands that caress move in random detours with no idea of what they are looking for, grasping and probing without wanting an end. The body tenses up, hardens, heaves and grapples, pistons and rods of a machine that has no idea of what it is trying to produce. Then it collapses, leaks, melts. There is left the coursing of the trapped blood, the flush of heat, the spirit vaporizing in exhalations.

There is the horrible in lust, and lust in the fascination with the domain of horror. The landscape

of horror is strewn with Hieronymus Bosch and Salvador Dali bodies with faces softening and oozing out of their shapes, limbs going limp and shriveling like detumescent penises, their extremities melting and evaporating, flesh draining off the bones, bones crumbling in the sands. This horror, which does not trouble our minds which compulsively fix substances in their boundaries and in their material states, troubles us in our loins. Lust is the dissolute ecstasy by which the body's glands, entrails, and sluices ossify and fossilize, by which its ligneous, ferric, coral state gelatinizes, curdles, dissolves, and vaporizes.

Muslims say they have to veil their women in public, because when lust stirs it takes over the whole of a woman's body. Arnold Schwarzenegger, to those who objected that most women really don't find these Conan the Barbarian bodies sexy, and anyhow how could anyone get it up spending as much time in the gym hoisting barbells as you do, answered, "Pumping iron is better than humping a woman; I am coming in my whole body!" The orgasm continues in the jacuzzi where the hard wires of the motor nerves dissolve into sweat and the pumped muscles float like masses of jelly.

Lust is flesh becoming bread and wine and bread and wine becoming flesh. It is the posture that no longer holds, the bones turning into gum. It is the sinews and muscles becoming gland—lips blotting out their muscular enervations and becoming loose and wet as labia, chest becoming breast, thighs lying there like more penises, stroked like penises, knees fingered like montes veneris. It is glands stiffening and hardening, becoming bones and rods and then turning into ooze and vapors and heat. Eyes clouding and becoming wet and spongy, hair turning into webs and gleam, fingers becoming tongues, wet glands in orifices.

The supreme pleasure we can know, Freud said, and the model for all pleasure, orgasmic pleasure, comes when an excess tension confined, swollen, compacted is abruptly released; the pleasure consists in a passage into the contentment and quiescence of death. Is not orgasm instead the passage into the uncontainment and unrest of mire, fluid, and fog—pleasure in exudations, secretions, exhalations? Voluptuous pleasure is not the Aristotelian pleasure that accompanies a teleological movement that triumphantly reaches its objective. Voluptuous pleasure engulfs and obliterates purposes and directions and any sense of where it itself is going; it surges and rushes and vaporizes and returns.

To be sure, blond hair represents for Thais as for Nietzsche the master race, candlelight and wine represent grand-bourgeois distinction and raffinement, leather represents hunters and outlaws, diamonds represent security forever. But lust cleaves to them differently. Encrusting one's body with stones and silver or steel, polishing one's skin like alabaster, sinking into marble bathtubs full of champagne or into the soft mud of rice paddies, feeling the ostrich plumes or the algae tingling one's flesh like nerves, dissolving into perfumed air and into flickering twilight, lust surges through a body in transubstantiation.

Libidinous eyes are quick, agile, penetrating, catching onto the undertones, allusions, suggestiveness of the act—responding to the provocation in the Janis Joplin number being done by a male Thai, the looks are parries in the intercontinental sex duel. The eyes of lust idolize and fetishize the representation, metallize the crepe the performer has covered himself with, marbleize the powdered poses of the face and arms, enflame the body strapped in those incandescent belts and boots. About the materialization of these idols

and fetishes, there is radioactive leakage; the castes, classes, cultures, nations, economies collapse in intercontinental meltdown. Wanton hands liquefy the dyadic oppositions, vaporize all the markers of différance into a sodden and electric atmosphere.

Lust does not represent the self to another representative; it makes contact with organic and inorganic substances that function as catalysts for its transubstantiations. Lust does not transact with the other as representative of the male or female gender, a representative of the human species; it seeks contact with the hardness of bones and rods collapsing into glands and secretions, with the belly giggling into jelly, with the smegmic and vaginal swamps, with the musks and the sighs. We fondle animal fur and feathers and both they and we get aroused, we root our penis in the dank humus flaking off into dandelion fluff, we caress fabrics, cum on silk and leather, we hump the seesaw and the horses and a Harley-Davidson. Lust stirs as far as does Heidegger's care which extends to earth and the skies and all mortal and immortal beings in thinking, building, dwelling—muddying the light of thought, vaporizing its constructions, petrifying its ideas into obsessions and idols, sinking all that is erect and erected back into primal slime, decreating all dwelling into the Deluge that rises. It is lust that, in Tournier's novel Friday , embraces Robinson Crusoe in the araucaria tree:

He continued to climb, doing so without difficulty and with a growing sense of being the prisoner, and in some sort a part, of a vast and infinitely ramified structure flowing upward through the trunk with its reddish bark and spreading in countless large and lesser branches, twigs, and

shoots to reach the nerve ends of leaves, triangular, pointed, scaly, and rolled in spirals around the twigs. He was taking part in the tree's most unique accomplishment, which is to embrace the air with its thousand branches, to caress it with its million fingers. . . . 'The leaf is the lung of the tree which is itself a lung, and the wind is its breathing,' Robinson thought. He pictured his own lungs growing outside himself like a blossoming of purple-tinted flesh, living polyparies of coral with pink membranes, sponges of human tissue. . . . He would flaunt that intricate efflorescence, that bouquet of fleshy flowers in the wide air, while a tide of purple ecstasy flowed into his body on a stream of crimson blood.[6]

Lust is not a movement issuing from us and terminating in the other. It is the tree that draws Robinson, holds him, caresses his breath with its million fingers. "The sea that rises with my tears"—obsessive line of a lovesong in Gabriel Garcia Marquez's novel In Evil Hour.[7] Lust of the sea, of the polyps liquefying the coral cliffs, of the rain dissolving the temples of Khajuraho, of the powdery gypsy moths disintegrating the oak forests, of the winter winds crystallizing the air across the windowpanes.

There is a specific tempo of the surges and relapses of lust, there is a specific duration to transubstantiations. For the sugar to melt, il faut la durée. But the turgid time of the wanton contact is not the time extended by society. The associations that form society first establish an extended time in which the carnal pleasure of contact with another can be interrupted and resumed. This time is a line of dashes in which compensations for what is spent in catalyzing

another become possible, an extended time in which the water that is turned into wine and consumed can be turned back into water once again.

In society one associates with another—for portions of the other, for the semen, vaginal fluids, milk of the other.[8] The association first extends an interval of time in which one portion can be poured after the other. Transubstantiations become transactions, become coded, become claims, to be redeemed across time, claims maintained in representations.

One associates with another—for parts of the other, for the tusks set in his nostrils, the fangs implanted in his ears, the plumes arrayed in the hair of this lord of the jungle who has incorporated the organs of the most powerful beasts of prey into his body. The association extends a stretch of time in which the transfer of these detachable body parts of his bionic body into yours can be delayed, a time in which the representation of self and the representation of the other forms.

One associates with another—for prestige objects, for productive commodities; one transacts with representatives of oneself and of the other. The association extends the infinite time of the libido, of desire which is desire for the infinite. A time to transact with the phallic objectives, the transnational corporation, the corporate state, the continent of which one is a representative.

When, in the midst of social transactions, there is contact with the substance of the other, and lust breaks through, it breaks up the extended time of association with its clamorous urgency. But sometimes the extended time of society of itself disintegrates.

Lust throws one convulsively to the other; its surges and relapses break through the time of transactions to

extend the time of transubstantiations. Shall we conceive of the transaction with representatives of self to function to postpone, control, exclude, suppress the surgings of lust?

Theater, which represents transactions with representatives of self, represents society to itself, but also opens up a space of its own outside society. In its absolute form, transvestite theater, does it travesty, parody, undermine, consume all our representatives of self, in an implosion of all our simulacra, leaving, as Baudrillard says,[9] the absolute of death alone on the stage? Or darkening a space for the naked surgings and relapses of lust?

There is something not said in the absolute, transvestite theater, where one dares everything. Is it transposing or releasing, subverting or trumpeting lust? That is its secret. The power to keep its secrets is the secret of its power.

Secrecy can be a force that exalts and sanctifies ritual knowledge. It can function to maintain the identity and solidarity of a group. The secrecy of individuals can determine the division of labor. The power to deny access to knowledge can constitute certain individuals or groups into subordinates. Secrecy can be a force to maintain a friendship on a certain level and in a certain style; I may choose not to reveal what I did last night, not because I did anything that you should or would object to were I to explain the whole context, but because I choose to avoid a confrontational relationship with you, I value the affable and ingenuous tone of our interaction, where each of us spontaneously connects with what the other says. The one who can say and also not say can make intentions and instincts that circulate at large his or her own.

The established practice of reserve makes it hard to confront liars, and thus maintains a social space for different compounds of knowledge, fantasy, and ritual behavior. To lose face for a Thai is not simply to feel embarrassment; it is to feel loss of one's defining membership in overlapping groups and loss of the social attributes of position. The importance of keeping up appearances, and of the presentation of respectfulness, unobtrusiveness, calmness, of avoiding saying things in opposition to what is expected not only organizes social interaction but penetrates even into the psychological attitudes of Thais toward themselves. "This attitude may go so far as his not wanting to engage in a private self-analysis whose result might be inimical to his own self-image."[10]

The walls of secrecy fragment our social identity. One is not the same person in sacred and in profane places, in crowds and behind closed doors, in the day and in the night; one is not the same person before different interlocutors. There are politico-economic motives that enjoin us each to be individuals, enduring integral subjects of attribution and responsibility. The immense field of ephemeral insights, fantasies, impulses, and intentions that link up in disjointed systems are forced to somehow form an individual whole in our bodies.

Our theories continue to conceive this whole either as an isomorphism between strata, a distributive organization of different behaviors for different contexts, or a dialectical sublation of each partial structure and phase in the succeeding one. But these paradigms do not succeed in making intelligible our personal identity. The intrapsychic organization, whether isomorphic, distributive, or dialectical, would be something general. It would give us the identity of a minor, a

father, a person, subject of rights and obligations, a citizen, a chicano or a Wasp. But for each of us, our personal identity is not simply a molecular formula of continual knowledge and skills; it is a singular compound of fragmentary systems of knowledge, incomplete stocks of information and discontinuous paradigms, disjointed fantasy fields, personal repetition cycles, and intermittent rituals.

In what psychoanalysis catalogued as multiple personality disorder, two or more persons inhabit the same body. But when Freud identified the unconscious, an infantile and nocturnal self that does not communicate with the public and avowed self, he generalized the phenomenon of multiple personality disorder, no longer a rare and aberrant case, but the case of each of us. Then one can drop the notion of "disorder"; a division of one's psychic forces, each system dealing with its own preoccupations, noncommunicating with the others, may work quite well. Rather than deal with all her problems with the integral array of her methods and skills, the self-assured office manager closes off the rape victim she also is and will be exclusively when she walks out of the office at night. The wall of sleep falls over our responsibilities of the day, and our infantile self is free to explore again the tunnels on the other side of the mirror.

Freud first explained the split in each of us by the concept of repression; the content of the unconscious would be produced by a censorship that represses representations from consciousness. But repression proves to be a shifty concept. In order to repress a representation, the censorship would have to represent that representation; repression is a contradiction in terms or an infinite regress. The censorship the child installs within himself is an interiorization of the decrees of

the father. But why does the father repress? Because he was repressed as a child. Another infinite regress. Freud saw that he was left with the fact that there is repression in the human species and the enigma of that fact. If we recognize the vacuous nature of the explanation by repression, we are left with these multiple psychic systems in our body, and walls of noncommunication between them. These walls of secrecy function in multiple ways.

It is one of the functions of walls of secrecy to maintain a space where quite discontinuous, noncommunicating, nonreciprocally sublating, noncoordinated systems can coexist. A space where episodic systems can exist, where phases of one's past and of one's future can be still there, untransformed and unsublated. Behind multiple generic identities, each of us builds his or her personal identity with inner walls of secrecy.

It is too simplistic to suppose that the libidinous desire in us—which represents the self and makes the self a representative which transacts with representatives of others who are representatives—functions to suppress, control, or mask the lustful body surging and relapsing in its transubstantiations. The noncommunication between libidinous desire and lustful transubstantiations can function to maintain the identity and solidarity of one's libidinal representation of self, to exalt and consecrate it. It can function to establish a division of labor between libidinous desire and lust, each in its own sphere and time. It can function to maintain an intrapsychic space for different compounds of knowledge, fantasy, and repetition compulsions.

Desire is desire for the absent, for infinity; libidinous eyes are quick, agile, penetrating, catching onto the undertones, allusions, suggestivenesses,

crossindexing. They are also superficial; they see the representation of a self and the self that is a representative. If they do not penetrate the wall without graffiti behind which lust pursues its transubstantiations, this wall may not at all function to exclude and to repress. It may function to maintain a nonconfrontational coexistence of different sectors of oneself. One may value an affable relationship with the beast within oneself. One may not want to penetrate behind that wall, not out of horror and fear of what lies behind, but because one may choose to be astonished at the strange lusts contained within oneself. One may want the enigmas and want the discomfiture within oneself.

After the Sambódromo

After the Sambódromo was written in Rio de Janeiro in 1993.

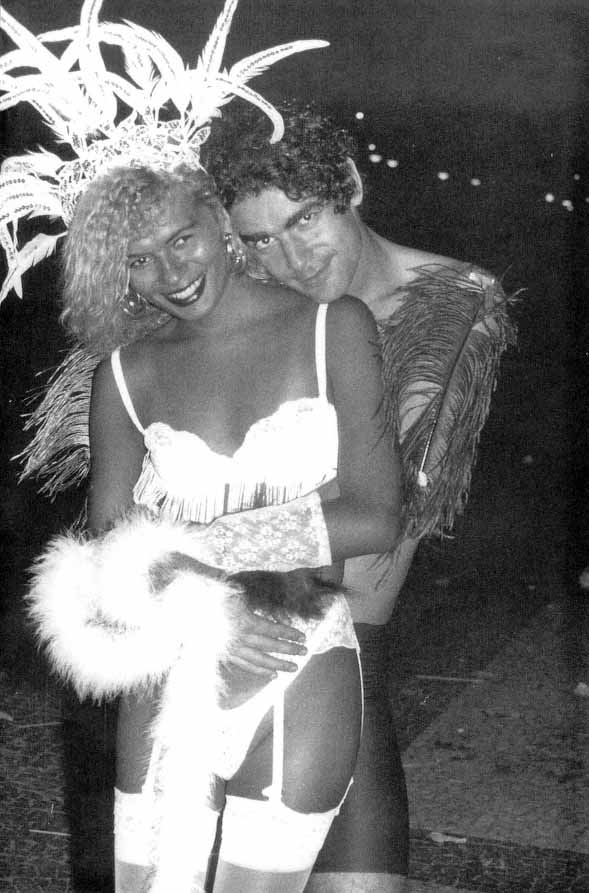

Carnaval in Rio. In the Sambódromo, the great escolas de samba parade, dusk to dawn, for four nights. Each escola announces its arrival at the far end of the Sambódromo by first making the night pound and the stars dance with fireworks. The samba begins, the song is sung a cappella during the whole length of the time of the passage. Each escola consists of from two to five thousand dancers. They dance in massed groups, alas , separated by duos of banner-bearers doing intricate dances at speeds the eye cannot follow, enormous floats called alegorias , and passistas —mulatas on spike heels and men doing gymnastic feats. Massed banks of older women in bouffant hoop skirts twirl, each alternating the direction of the next one, as they dance. They are called baianas , recalling the women who came from Salvador de Bahia in the last century; it was from their macumba-trance processions in the streets of Rio that Camaval evolved. The bateria —percussion band of two to four hundred, with drums, cymbals, tambourines, and instruments of African origin—is in the middle; by the time it has arrived at the bank of the bleachers where you are, it has risen up to overwhelm the samba song and it is impossible to sit; everyone in the bleachers is dancing.

Our idea of a parade is a representation of society; there are the flag-bearers, the veterans of foreign wars, the mayor and police chief, the firemen, the nurses, the football team; there are enormous advertisements

of sponsors. Here, none of that. The escolas are from the slums, the favelas , not from the glittering high-rise districts of Ipanema and Barra da Tijuca. Not even the master of ceremonies, choreographers, or funders are in the parade.

The escola is a whole theater; the theme sung in the samba is developed by the succession of banks of massed dancers and the alegorias. The theme of this year's grand-prize escola was water—the water of the ocean, of the Amazon, of cascades and waterfalls, wells and ponds, showers and storms. The dancers danced the beauty and the joy of water. Carnaval is about nothing but the joy of beauty and the beauty of joy. My dentist told me that he too had danced in the Sambódromo; you have to, it is an exhilaration that nothing else in life on earth can give.

People in the slums will put aside a few cruzeiros a month for years for a costume to be able once in their lives to dance the samba. The splendor of the costumes, used but once, is astonishing; one has seen the like only in the Follies Bergères in Paris or in the Sands at Reno. In the richest cities of the world there are only a few cabarets which can afford to costume a few dozen dancers with such extravagance. I stood there thinking that I was seeing what must represent the total ostrich-plume production of Africa, the total peacock-feather production of India. Some of the costumes are so heavy that the dancers have to be borne on floats, where they samba under enormous head-dresses and splayed sunbursts of metallic fabrics and plumes supported by the scaffolding of the float.

At the same time as the parade in the Sambódromo, an equal multitude of people are parading, for three days and nights, in the Avenida Rio Branco. The neighborhood clubs, the blocos , are parading in

the Avenida 28 de Setembro. Carnaval balls are organized in every building, every hotel and club that has a hall. Every band that exists in Rio is out playing in street corners or along the beaches. People who were not able to costume for an escola dance about these bands, the poorest slum-dwellers at least costumed with some dyed chicken feathers.

I could not but wonder at the sheer expenditure involved, in this Brazil undergoing the worst economic collapse of its history, and reading each day as I was of the coalition of First World countries spending a billion dollars a day to fight Iraq for control of Kuwaiti petroleum.

What is distinctive about the Brazilian Carnaval—say, by contrast with carnival in Venice—is its carnal exuberance. In Venice, the face is masked, the individual is incognito in a statuesque hierophany. Here the costume, a sunburst of collars and capes and a nimbus of arcing plumes, is arrayed as a sort of shrine around the bared body of the dancer. The samba, a virile dance, is not a dance of melodic figures of corresponding dancers, but of the legs and gyrating buttocks, which must be bared. Female nakedness glows in the midst of glorified versions of culturally feminine or masculine garb; male nakedness glories in the midst of culturally masculine or feminine garb. The escola Estácio de Sá, whose theme is "The Dance of the Moon," is gay; 70 percent of its voluptuous women are transvestites or transsexuals. In Venice individuals compete for the most extravagant, original, striking, but also distinctive costume. Here, everything is communal; each escola parades in alas , troupes of three to four hundred, costumed the same. Being extravagantly gorgeous is essential to Carnaval, but so is being part of a collective movement and joy

being danced out by hundreds of others in a banked mass. The rows of dancers joyously singing the samba zigzag from one end of the avenue to the other as they advance, each dancer, when he or she reaches the bleachers on either side, throwing out the samba into the crowds, eyes scanning for people intoxicated to dance and sing with. The virtuoso dancers high on the alegorias are not putting on a show to be applauded; they are casting forth spirals of exuberance into the crowds. The parade is not an exhibition of individuals, but a surge of giving, giving carnavalesque joy to the fireworks-illuminated beauty of the massed people of Rio.

Seeing sambistas whose costumes were inspired by those of ancient Egypt, I thought that the processions of pharaohs, emperors, kings were surely never this resplendent. They paraded down the avenues of their capitals in hieratic costume and with ancient crowns and staffs, to fix their iconic figures in the minds of the people as they built triumphal arches and pyramids to perpetuate their individuality against the erosion of time. Here the art of the most gifted designers of the city who have worked all year on these costumes, drawing inspiration from the arts of all cultures and epochs, is but for this night. The dancers whose bodies are glorified by them in the Sambódromo stream out into the streets of the city, dancing till exhaustion, abandoning their costumes to the street sweepers before going to their homes.

Around the Sambódromo, there were dances that were more than joyously beautiful.

Anyone who has, himself, scrambled down the Olduvai Gorge and tried to make a chipped-stone tool from a pebble found there acquires a personal appreciation

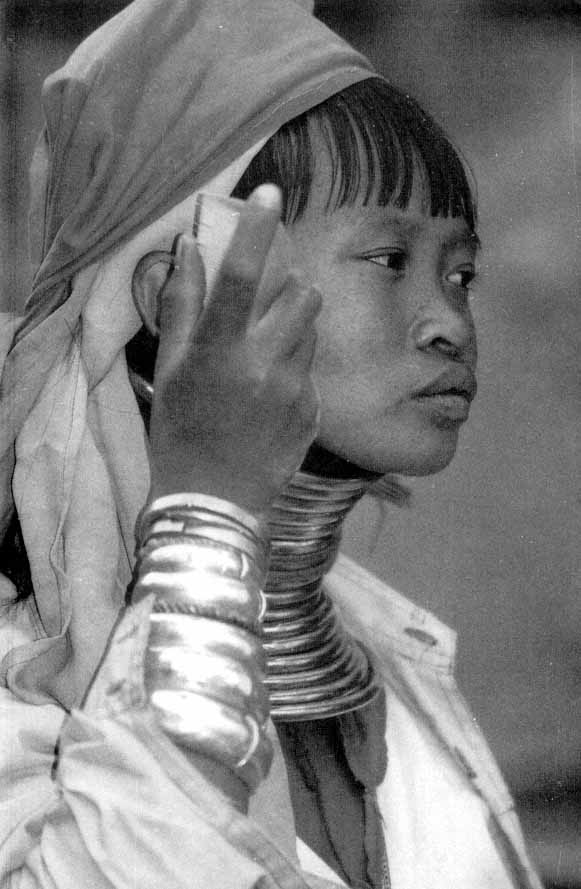

for the skills and perseverance of our "primitive" ancestors. But when he tries to duplicate the hundreds of minute and regular flakings necessary to make one as symmetrical as those they made, a symmetry without any real utilitarian function, he recognizes that a sovereign drive for beauty is as old as humankind. Leopards, jaguars, pumas—splendid in color and form, powerful, graceful, clairvoyant, intelligent—and certainly not human beings, are the most gorgeous forms of life. It is not surprising that humans, evolved or devolved from other animals, derived their sense of beauty from other animals. Animals have evolved veritable organs to be seen:[1] iridescent fins, lizard headcrests, arrays of shimmering plumes, mountain-sheep horns, extravagantly crayoned baboon buttocks—lures for the appreciative eyes. Every culture in humankind, besides being cultivation of the resources of nature, is a cultivation by humans of their own nature. Not only an evolutionary adaption to ecological conditions and social enterprises, but elegance of musculature and contours, colors and garb; choreography of eyes, gestures, and gait; artistry of caresses, intonations, murmurs, laughters.

It is one thing to find that the structure of a flower, its stamen and its protective and insect-supporting petals, is fashioned so as to fit perfectly our notion of the function of a flower; it is another to find its form and colors beautiful. We really do not possess a set of concepts that determine our judgment as to what is beautiful; as we go we find that the plastic forms of human bodies, their contours, their surfaces are beautiful like we come to see the beauty of sand dunes and the geometry and sheen of lilies; we find beauty in somber, blotched, or veined skin like we had come to see the beauty of mottled flowers or fallen leaves.

Yet we also have a sense of ideal human beauty. Ideal human beauty, like the melodic movements of a herd of zebras in the savannah, the beauty of dragonflies crystallizing in sunlight, involves a sense of a way of life whose felicity is divined. A face can attract us by the fire in its eyes and the vivacity of its organs, the spiritedness of its substance, the exceptional expressiveness of the movements that form and fade across it; the harmony or vigor of its contours and tones themselves evoke the benevolence or exuberance of the human habitat. This kind of bodily beauty makes us thoughtful while dissolving the fixity of our own ethical notions. Certainly the first impression of one who arrives among the Lani of Irian Jaya or the Ifugao of the Central Luzon Cordillera is one of physical splendor; it irresistibly contains a sense of a people who know how to live in the environment and who know how to live blessedly. The more one contemplates their physical poise and grace in different lights and in different confluences, the more enigmatic but also the more compelling seems to be its ethical force. Reading anthropological literature, however, which derives every trait of their mores from ecological and political reasons, reduces their beauty to anatomical adaptation.

In the crowds and nights of our metropolises and in our wanderings in towns and fields, we are attracted to the beauty of telephone linemen, nurses, inner-city schoolteachers, bikers, rice farmers, miners, street kids in Marrakesh, capoiera fighters in Salvador, women construction workers in Leh. In the beauty of their bodies we divine so many kinds of talent in living magnanimously. What pleasure we find in discovering them! There are so many who do not know! "It was Aharon Markus, the pharmacist, who put forth

the supposition that after thousands of years of existence on this earth man was perhaps the only living creature still imperfectly adapted to his body, of which he is often ashamed."[2] The ethical sense in us is elaborated not by concepts and reasons, but by a sensibility attracted to those who are artists of their lives.

Like stormy seas and sandstorms in deserts, like minute and simple forms of life divined beneath the efforts of vision, and like condors soaring over the High Andes and leopards passing in ferocious rain-forest nights, the human body can give rise to the sense of the sublime. Immanuel Kant would say that would happen when the scale and pattern of a human presence exceeds our power to circumscribe it, when the grandeur of the emperor or the forces of the hero exceeds our powers of perception and give rise to the idea of the superhuman or the divine—and this idea that rises in us radiates in intellectual pleasure.[3] Yet does not the self-satisfaction in the ideas one forms diminish the grandeur of the human body and extinguish the feeling of sublimity before it? Does not the sense of the sublime in the sight of a human body instead empty out the ideas of the superhuman and the divine?

The material things do not lie bare and naked before us; they are there by engendering perspectival deformations, halos, mirages, scattering their colors in the light and their images on surrounding things. Human bodies too move in the world engendering profiles and telescoping images of themselves, casting shadows, sending off murmurings, echoes, rustlings, leaving traces and stains. Their freedom is a material freedom by which they decompose whatever nature they were given and whatever form culture put on

them, leaving in the streets and the fields the lines their fingers or feet dance, leaving their warmth in the hands of others and in the winds, their fluids on tools and chairs, their visions in the night. Bodies do not occupy their spot in space and time, filling it to capacity, such that their beauty would be statuesque. We do not see bodies whose form and colors are held by concepts we recognize or reconstitute. We do not see bodies in their own integrity and inner coherence. We are struck by the cool eyes of the prince of inner-city streets, moved by the hand of the old woman covering the sleep of a child. We are fascinated by the hands of the Balinese priest drawing invisible arabesques over flowers and red pigment and water. Our morning is brightened by a slum-dweller whistling while hauling out garbage. We hear the laughter of Guatemalan campesinos gathered about a juggler, like water cascading in the murmur of the forest. When we are beguiled by the style with which the body leaves its tones, glances, shadows, halos, mirages in the world, we see the human body's own beauty. In the decomposition in our memory, in so many bodies greeted only with passionate kisses of parting, we have divined being disseminated a knowing how to live trajectories of time as moments of grace.

When the scale of a human presence scattered across vast spaces seems unconceptualizable, as also the utter simplicity of certain gestures and movements seems undiagrammable, we have before a human body a sense of the sublime. The sublimity of a body departing into the unmeasurable spaces make the ideas we form of the superhuman and the divine seem like second-rate fictions. The sentiment of the sublime is a disarray in the vision, a turmoil in the

touch that seeks to hold it, a vortex in our sensibility that makes us ecstatically crave to sacrifice all that we have and are to it.

Human warmth in the winds, tears and sweat left in our hands, carnal colors that glow briefly before the day fades, dreams in the night, patterns decomposing in memory, sending our way momentary illuminations: bodies of others that touch us by dismembering. The unconceptualizable forces that break up the pleasing forms of human beauty and break into the pain and exultation of the sublime are also delirium and decomposition. Not sublimity in the midst of abjection: sublime disintegration, sickness, madness. The exultation before the sublime is also contamination. Porous bodies exhaling microbes, spasmodically spreading deliriums, viruses, pollutions, toxins.

Rita Renoir performed in a cabaret in Montparnasse. What to call this performance? Not dance; it did not elaborate an artistry of positions and movements. Not one-woman show; she was not, like Marlene Dietrich or Madonna, creating a legend or myth of herself. A female body dismembering and transmigrating. In a hooded black robe, she emerged; the light glowed about her hands clasped, hands made for blessing. A leonine mane hid her face bent over her body in grotesque and obscene nakedness. The shame and malice of a little girl glowered in a slyly bent torso. Hysteria raged in a convulsed stomach. Her bared vagina threatened between powerful thighs. Blood and milk glistened on breasts and flanks. Laughter hurled painfully against one's ears. Strange garglings and hissings seduced strangers in the dark. Debauchery splayed her limbs. Joy strangled her throat. Terrible loneliness shivered in her. Virility and blood-lust hardened her

legs. The majestic figures of august goddesses mineralized her. Longing and interminable waiting ravaged her strides. Blissful and lethal abandon made her weightless and floating.

After an hour she would climb over the seats into the audience inviting people to get on the stage, disrobe, and interact with her. Handsome men showed foolish and unwieldy meatiness. Old men revealed torsos wonderful as those of scorpions. Young men dressed in jeans and black leather postured their engineered and tedious pumpings over limp penises. Elegantly dressed young women disrobed and showed bodies stilted before hers to the point of ugliness. Stout middle-aged women glowed with carnal tenderness.

I went weekly for a month, brought friends. Then I left Paris for the Easter break. When I came back, the cabaret was closed and I could find out nothing from shopkeepers in the adjacent buildings. The next season I returned to Paris, and could learn nothing of what had become of her. Ten years later, I asked a friend I had taken to see her, and he told me that he has never seen any mention of her in the press. I cannot believe she has secluded herself, like Marlene Dietrich, with her press reviews and her celebrity. In Karachi and in Quelzaltenango, on Swayambhunath and on Komodo island, I looked for her.

A Noite dos Leopardos: for the past four years in the Teatro Galeria in Botafogo, Eloina dances with her troupe of bodybuilders. Eloina, with abrupt and precise movements and consummate skill, is supremely, vaporously, impudently, voluptuously feminine. Like Nico, who was so beautiful only because her femininity appeared so completely put on, Eloina is able to separate so completely her vamp, diva, grande dame,

courtesan, czarina, and pop superstar femininity from femaleness that the wonderful symmetry and proportions of her contours and features seem completely to obey aesthetic laws. But Eloina also presents the specific beauty of the distinctively female body. Clad, as it were, only in chains of jewels, the satiny substance of her full round breasts glow in the light. On spike heels, her dance does not involve a lot of samba foot-work. With her full thighs, she gyrates her pelvis in floating rhythms, and it is as though all the parts of her gyroscope body—her arms which strike out like rays from it and bend back elegantly upon it, her fingers which echo the circular movements, her long auburn hair reversing its spirals—were assembled to present the beauty of the pelvic movements. A pelvis abstracted from any teleological destination to maternity, a pelvis being created just for its beauty. The idea that Eloina is biologically male floats utterly detached from what the eyes see.

Eloina dances with a troupe of a dozen bodybuilders, who walk blasé and impudent on the wild side, engage coldly and maliciously in knife fights, hurl themselves nonchalantly at one another in capoeira, a sort of voluptuous martial art evolved in the bored black slums of Salvador, prowl, slink, hiss, and leap on all fours in leopard masks. Their musculature is completely generic, devoid of the specificities that individual occupations or sports inevitably inscribe on a body—not miners' bodies, peasants' bodies, swimmers' bodies, power-lifters' bodies, dancers' bodies. Not personal bodies. Bodies upon which are strapped a musculature that obeys no finality of development save that of its own maximum and concordant assertion. Not male-sex bodies, a musculature that like an accoutrement can be vested upon the invisible theater

of knife fights in the night or the hunt of leopards. The pleasure of the eye which contemplates the proportions and symmetry of these bodies is inwardly rent by the spectacle of terrifying feral instincts.

The climactic moment comes when, just before the final apotheosis, these titans appear in full erection, flaunting their hard and massive cocks. They do not gyrate and pump their torsos, and do not dance lewdly, they advance with movements contrived to hold the eyes on the sooty glow of their knot-veined erections. Our eyes are in a state of shock; this position in which they are forced is so contrary to what they wanted that one protects oneself with a whole swarming of defensive ideas, Freudian ideas: would not their wives or girlfriends be completely cheapened and mortified to see them here? Are not these supermales in fact sluts, who are not men enough to get real jobs? What kind of a man would make exhibiting virility his occupation, save those who are in fact impotent? Are they not in fact narcissists, bodies that, more than fascinated with their own images, have projected themselves completely into images of themselves? But it is just through all these questions with which we undermine the reality of those erections that we also disconnect in ourselves any libidinal or emulatory interest in them. No longer male, biological, purposeful whether for copulation or for voluptuous contact, bared of all phallic, political, economic symbolism, here the erection is asserted for itself, dissipates all finalities we may conceive for it, rises in savage power for inconceivable intrigues.

One evening I was accosted by a man in rags I assumed needed a handout, and when I handed him a crumpled bill he gave me a ticket. It was in Manaus;

here, a thousand miles from the sea, the black waters of the Rio Negro coming from Columbia join the yellow waters of the Rio Solimöes, seven degrees colder, coming from Peru, to form the Amazon proper, which is here, at its starting point, eight kilometers wide and three hundred feet deep. Manaus was the port city of the rubber boom, which abruptly came to an end in 1912 when the Malaysian rubber plantations began to flood the world market. I examined the ticket he had given me; it was for the Teatro Amazonas, the legendary opera house built during the rubber boom entirely of stone and marble imported from Italy and decorated by artisans and painters from all over Europe; outside the sidewalks leading to it are of Portuguese marble and the roads of rubber bricks. It had been seventeen years since an opera company had come to perform in it.

"Se o espírito de Deus se move en mim, eu canto commo o Rei David"—"If the spirit of God moves in me, I will sing like King David"—Edson Cordeiro rose from below singing. He is very small, with thick black eyebrows over huge eyes and a great mass of wild hair well below his shoulders. The voice swelled with a body, color, range, and expressivity that one hears and still cannot believe. His second song was something Yma Sumac used to do, as only she could—the Peruvian Inca with the five-octave-range voice. Then he did coloratura arias from Verdi and Puccini. None of the pinched falsetto of the counter-tenor in his soprano, rich and vibrant, it filled the hall with its high-altitude acrobatics. He sang "The Queen of the Night" from Mozart's Magic Flute over the equally amazing Cássia Eller, a young woman, hoarsely bawling out Mick Jagger's "I Can't Get No Satisfaction." He sang flamenco, songs of classical and

contemporary Brazilian composers, blues, religious hymns, Janis Joplin, Prince, and hard rock. There was no intermission. He silenced the applause by immediately beginning to sing again, his voice moving across five octaves, abruptly shifting into another totally different musical universe, each time with purity and gorgeousness of tonal body and passionate interpretation. One would have been enthralled to hear him in any one of these voices the whole evening. The gospel singing brought to the opera house in the midst of this enormous black slum city the fervor of another continent. People dressed in street clothes came through the audience to join him on the stage. The Spirit in the Dark flashed in his eyes and kindled a glossolalia of entranced melodies from him, and jumped across the singers on the stage and sprayed flares across the possessed audience. It turns out, I learned from the paper the next day, that he himself was raised in an Evangelical cult. It was there that he began speaking, and then singing, in tongues. He left home at the age of sixteen and sang in the streets for cruzeiros until two years ago. Now he is twenty-four years old.

His body is very slight, his arms lean, a very adolescent body. He wore soft black leather pants and a soft black leather tank-top, and black boots with high red block heels. Over that he flung on different smock-shirts—a white one, then a transparent one with silver designs, then a red embroidered-silk, Chinese-sleeved one, to finish in a black leather jacket with spiked Kabuki shoulders.

In the flamenco, a duet with Maridol, a professional flamenco singer, his torso arching back to the floor, his arms and fingers were doing even more intricate and sinuous gyrations and arabesques than

hers. In the heavy metal, his body crouched and leapt with heaving crotch, stopping suddenly, his derriére vibrating with the drumheads. Physical panic vocalized the Raul Seixas song "Para Nóia." One thought what a dancer and actor he also is. Except that it is not that separate thing, dancing, or acting. It is that the song sings his whole body, is being sung with his arms, torso, legs, furling, flying, floating in the smoldering or blazing spotlights across the vast spaces and heights of the stage.

In the concert hall, while one hears the marvelous beauty of the vocalization, one's eyes stray over the breasts, the fluid gown, and the thighs of the soprano, or one's eyes wander over the face, shoulders, and torso of the baritone and see how handsome a male body he is. With Edson Cordeiro, so many different kinds of female voices of so many different kinds of women are sung with his body that it loses anything biologically male in it. But it also does not have the ample voluptuous excess of female breasts, thighs, that softness of arms and hands that shows through on singers who look female. There is not a carnal thickness to the pure melody of his kinesics that would solicit touch and invite caresses. Everything that is palpable, opaque tissue, is gone from his body, which is, I thought, like a mobile Japanese calligraphy: an instantaneously made swirl of strokes is so expressive that you no longer see the hair marks of the brush and the opaqueness of the ink.

His mouth wide with gleaming teeth is the radiant organ of the song. His eyes flash under those thick black eyebrows that arc very far back across his brow. The spotlight beams tangle in the black mane of his hair. Yet even when doing the most indulgently kittenish Janis Joplin song, his face does not

become feminine. It is the only part of him that seemed to me androgenous: the coquettish eyes, the wide sensuous lips on a face whose bony leanness and black cast to the upper lip and chin keep it male.

"Se o espírito de Deus se move en mim, eu canto commo o Rei David," he sang once more from the back heights of the stage as the curtain fell. When he came out to the front edge of the stage to receive the wild ovations of the crowd, I saw how very small he is—he must be barely five feet high. A size not now magnified by glory, for in him there was only a total, innocent joy in song which his radiant face now received swelling back to him from the enraptured crowd.

The transvestite, by outdoing women, doubles up the number with his residual maleness, making of the glamour also an outrage; here the residual maleness itself was transubstantiated into immateriality of song. The beauty was no longer also a way for sexual marginals or members of racial minorities to gain entry into some kind of social acceptance. It was pure, disinterested, absolute. The performance was entitled "Uma Voz"—A Voice—and indeed the wonder was not that a male could sing coloratura soprano arias, but that one voice could have mastered so many different kinds of resplendent lyricism. It was more than stunningly beautiful; it filled the great Opera House, surged across Manaus, sent tidal waves over the Amazon, departed into the jungle and the skies.

One night during Carnaval, there was a Michael Jackson look-alike. Not in the Sambódromo, just having a drink at one of the balls. The same height, same huge eyes, infantile nose, thin lips and gleaming teeth, same cleft chin, same radiant, wild, vulnerable,

wanton look. He was also dressed and held his drink like Michael Jackson, and when he danced he danced indefatigably spidery Michael Jackson gambols. One couldn't help staring to try to see some details he had kept for himself: no, none. I realized I was in the presence of an individual in a radically new experience. No doubt there have been people, in the past twenty-five years or so that plastic surgery got going, who, having redone their hair, nose, breasts, like their ideal of beauty, decided to go all the way. A woman who would have redone herself after Elizabeth Taylor or Kim Bassinger could hide it sometimes, with a new hairdo and glasses. But Michael Jackson is a face more stamped in the public mind than any actress ever was, and so distinctive that there just is no way this individual can hide this face he now has—certainly not with shades. He could never go into a room anywhere and not be Michael Jackson. Michael Jackson himself is a product of plastic surgery. This Carioca has wiped away forever his own face to wear the face of a gringo who had wiped away forever his own face.

They say that Michael Jackson's nose is now loosening and beginning to sag. It needs periodic work. I imagined Michael Jackson now redoing everything—dying his skin, having the surgeon build a broad-nostrilled nose, thick lips—and down in Rio this Carioca undergoing the same metamorphosis. I imagined them meeting. They would not be mirror images of one another. Michael Jackson could never be at ease with him. It would be black magic, macumba to him. Already, here in this Carnaval ball full of transvestites, nobody talked or danced with him; their looks glanced off him. By himself, here in Brazil, this Michael Jackson exists, has a space. It would be de-

stroyed if the "real" Michael Jackson not only came here for a concert, but stayed six months. Clinging to the beauty he paid for in cruzeiros and pain, this Carioca would have to—would!—create the space for his single-mindedness, determination, and cool.

I thought that Manila was the ugliest of the sprawling cities of Third World countries whose rural and raw-material export economies have not ceased to decline since World War II. Unlike sordid Bangkok sinking into its muck, stinking Jakarta where but a third of the population has even access to potable water, and the black hole of despair that is Calcutta, there are not even, in Manila, the tatters of old Asian religions and cultures to be seen. Its soul, they say wryly, spent four hundred years in a convent and forty years in Hollywood. Four hundred years of Spanish machismo and forty years of U.S. marines. The climate is sticky and hot, and the air is poisonous in the streets choked with jeepneys hacking out black fumes. If you go out you get a headache in a half hour and will have to change your clothes and scrub the oily grime off your skin with soap. It is enough to defeat any quixotic idea of exploring the city one might have.

It was already 11:50 when I woke, the gut bilious with another bout of dysentery. The lobby was dark, the desk clerk asleep on a bench. Outside it was raining listlessly. I walked down streets at random, looking for a bar. Skeletal dogs yapped and howled, picking up from one another, long ahead of me.

Finally I came upon a San Miguel sign; behind the rusty corrugated metal door a dim light still glowed. Inside there were some tables and in the smoky haze a few drunken men bent over them.

A dusty radio coughed out rock'n'roll. On the far wall five women, in dirty dresses, their faces smeared with garish lipstick, looked at me. I sat down in the far corner. A man came to the table. He grinned slyly, showing bad teeth.

"Good evening, sir," he said. "Are you a Yank?"

"A beer," I said.

"Are you alone tonight?" he asked. "Will you have a companion?" He nodded ingratiatingly at the girls at the far wall.

"A beer, just a beer. San Miguel."

"I have very nice girls," he said, "very clean, not like on Del Pilar Street." He leaned over. "No diseases. I have virgin girl for you."

"No," I said as coldly as I could. "I want a beer." He brought the beer. I drank it and signaled for another.

The door pushed open. Outside it was now pouring. I made out in the dark someone dressed in an even more mini miniskirt and even more gaudy lipstick. She was drenched. The bartender yelled in Tagalog at her. She sat at the door. After awhile she came over to my table.

"Do you mind," she said very quietly, "if I sit with you? I don't want anything from you," she said hurriedly, to stop my answer. "I have some money." To prove it, she ordered a beer and paid at once. "I am alone too. It is very late."

I looked at her coarse hands and realized she was a guy. She had a threadbare satin blouse with several buttons missing, and a tangle of costume necklaces over it. On her feet there were muddy sneakers. In her shoulder-length hair she had stuck a now limp red rose. Her nose was bashed in and she had several

front teeth missing. I looked down. Then I looked up to smile.

"It is very hot in Manila," she said to my smile. "Excuse me, may I know your name?" "What country are you from?" "How long are you staying in the Philippines?" "Are you having a good time?" Then she stopped.

I said nothing for a long time. I ordered more beers. The bloated feeling in my gut died away. Some of the women along the wall left. I said, "What is your name?"

"It depends on the sun," she said, grinning wide, unconcerned over her missing teeth. "From sunrise to sunset my name is Mario. From sunset to sunrise my name is Maria." She laughed.

She looked at me and said, "Are you sad? Can I sing you a song?" She stood up, tucked in her blouse, tried to untangle some of her necklaces. She bobbed her head, and began to sing "Sad Movies Make Me Cry." She sang into the sputtering of the radio, pulled its canned racket into her own song, she sang louder and louder. She filled the room. The bartender looked vacantly from his chair; the men bent over the tables were beyond hearing. Her eyes opened wide and were lit with flash-fires as she rocked and danced under the bare bulb. Her fingers became soft and her gestures more and more melodramatic. No opera prima donna, no rock superstar, no tragedienne had ever been more splendid, no epic or theatrical or world-historical emotions more overwhelming. When she stopped, she began laughing, spasmodically, wildly, over her song, over herself, a laughter that swept through her whole body and stumbled and fell into itself and pealed out again and again. I was laughing, not sick or drunk. I was shaking with a hilarity that

swept away the yellow bulb, the tables, the room, that rolled away into the rain.

I looked at the polluted rain muddying my window and thought of the coral seas. I decided to leave Manila for awhile and go diving in Batangas. I checked the tourist office and some agents in the city for information about where to go, where to get diving gear. Her song and her laughter were in the room when I woke up. I broke out in laughter in the middle of lunch at a restaurant. Four days later I tried studiously to retrace my steps of that night, but did not find the San Miguel sign. I tried the next night again. On the third day I searched for it in the afternoon and found it. I asked the bartender where she lived. He sent a boy to look for her. They came back very soon. "Come to Cebu with me!" She looked uncomprehending. "Come let's look at the fish!" I said, and waited. Then she did laugh.

I did not rent a boat, even though the beach cottage owner said all the reefs near the shore were damaged by fishermen dynamiting them to stun the fish. She had put on a bikini and a red rose in her hair. The men at the dive shop looked at me and then down. They asked for my certification card and would rent only snorkeling gear for her. We carried the gear to the place where three palm trees shook their coarse combs over the powdery sand and transparent water. We avoided turning our eyes upward; the sun was blazing a hole in the sheltering sky. I put on the scuba gear and sank through into the bolts of light that flashed across the warm brine toward the cobalt blue abyss. Below there was surge, and after equalizing my ear pressure and adjusting my buoyancy compensator to float over the prongs of the coral banks, I abandoned any effort to direct myself or

swim anywhere. I pulled slices of bread from a plastic bag; damselfish, angelfish, Moorish idols, jackfish, barracudas swarmed about me. I turned over and saw her thrashing above, her laughter cascading through the snorkel in bursts of foam.

I stuck in my bathing suit the corroded half-shell of a pearl oyster and a live decorator crab that had stuck little shells and throbbing anemones all over its legs. I trapped a blowfish in my hands, and knocked it about a few times whenever it started deflating. When my airtank was empty, I swam to the shore. She sat on the sands, surrounded by the sad movies of shells and crabs and jellyfish and laughed and laughed and the waves were laughing against the sands and then turning back to roll their laughter over the Pacific.