Tapping and Defining New Power: The Press and Local Leaders

The atmosphere of rural Gipuzkoa and Navarra in June 1931 was like a cloud chamber with air so saturated that even slight radioactive emissions become visible to the naked eye. Two children whose own father did not believe them when they said they had seen the Virgin immediately attracted two to three hundred observers. In the following days, weeks, and months, in this atmosphere, other visions by other children and by adults, visions we would not normally hear about, left their marks. The impressions on these seers' minds held immense potential importance for the Catholics of the Basque Country, Spain, and Western Europe of 1931. These strong impressions are still available sixty years later in the form of memories and printed accounts.

The visions offered Catholics a source of new power or energy—power to know the future and to know the other world of heaven, hell, and purgatory, power that could heal, convert, and mobilize the faithful. The crowds that converged on Ezkioga even before the news came out in newspapers showed how much people wanted this knowledge and this intervention. Calling this power new implicitly accepts the local definition of what was happening, the

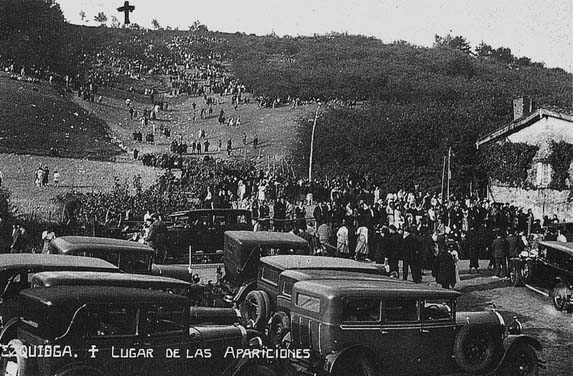

"The site of the apparitions." Crowd gathers on hillside, July 1931. Postcard sold by Vidal Castillo

truth of the divine appearances. But even believers would probably quality the idea that the power was new, because for them it would be a new version of a power very old indeed, the everyday power of God among them.

At Ezkioga this power was manifest in an unusual but hardly unique way. The Ezkioga parish church had bas-reliefs of Saint Michael appearing at Monte Gargano. Many Basque shrines had legends of apparitions. Lourdes was nearby, and well over a hundred thousand Basques had gone there and experienced firsthand the spiritual fruits of Bernadette's visions. The vision sites of Limpias (about a hundred kilometers northwest) and Piedramillera (about fifty kilometers south) were even closer. And Basque children knew about the apparitions of Fatima. The Ezkioga visions occurred during a period of enthusiasm within Catholicism in which the devout, in the face of rationalism, had come to believe that the old power was closer at hand, certifiable miracles were fully possible, and the supernaturals were easier to see.[15]

For apparition legends see Lizarralde, Andra Mari de Guipúzcoa and Andra Mari Vizcaya; Arregi, Ermitas de Bizkaia; López de Guereñu, Andra Mari en Alava; Peña Santiago, Fiestas; and Facultad de Teología, Santuarios. For Lourdes see Christian, Moving Crucifixes, 150, factoring in those who did not go on organized pilgrimages.

This kind of power came from the conversion of potential to kinetic energy. The potential energy lay in the Basques daily devotions, their normal attention

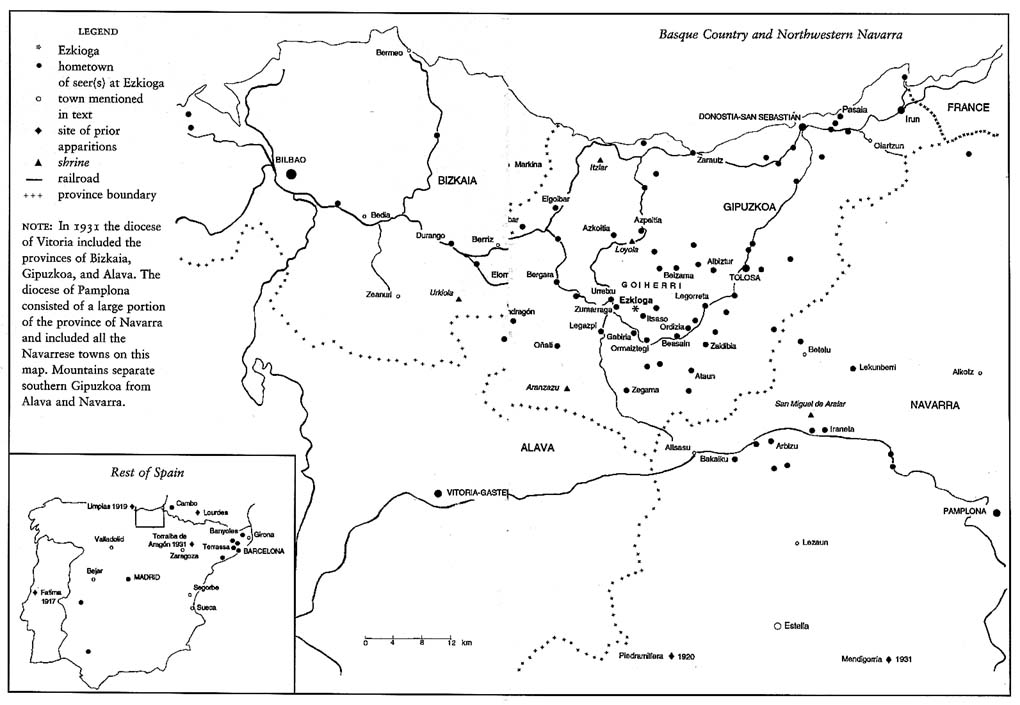

HOMETOWNS OF SEERS OF EZKIOGA AND TOWNS WHERE THERE WERE PUBLIC VISIONS

FROM 1900 UNTIL THE VISION AT EZKIOGA BEGAN ON 29 JUNE 1931

(map is on previous page)

to local, regional, and international saints. They deposited and invested this energy in daily rosaries, novenas, masses, prayers, and promises. They banked it through churches, shrines, monasteries, and convents. The church in its many representatives husbanded and administered it. The threat of the secular republic mobilized this accumulated devotional energy in the people of the north.

Tens of thousands of persons focused this power intensely on the seers. The seers were the protagonists, their stories and photographs in newspapers. Many of them seemed to feel in their bodies a tremendous force. Walter Starkie, an Irish Hispanist who wandered into Ezkioga and became for a few days in late July 1931 its one precious dispassionate witness, described a girl in vision as he held her:

I could feel the strain reacting upon her: every now and then a powerful shock seemed to pass quivering through her and galvanize her into energy, and she would toss in my arms and try to jump forwards. At last she sank back limp and when I looked down at her white face moist with tears I saw that she was unconscious.[16]

S 145.

As we will see, time and again beginning seers described blinding light and fell into apparent unconsciousness. The metaphor of great power was one that they themselves used. When they lost their senses, wept uncontrollably, or were blissful, they demonstrated this energy to observers.

How was this power tapped? Which visions made it into print and which are available only in memories? Who by controlling the distribution of news of the visions helped define their content? How did what the seers saw and heard come to address what their audience wanted to know?

The Basques and the Navarrese were more literate than most Spaniards. In 1931, 85 percent of Basques and Navarrese aged ten or older could read and write; the percentage was about the same for women as for men. The national average was 67 percent. Parents took elementary school seriously and teachers were important members of the community. This high rate of literacy ensured many avid readers for news of the Ezkioga visions.[17]

Ferrer Muñoz, Elecciones y partidos, 55.

For most Spaniards the news came largely from the reporters of the rightist newspapers of San Sebastián and Pamplona. In addition, the small-town stringers of these papers occasionally went to Ezkioga with busloads of pilgrims. Only on two occasions in July did writers for the more skeptical El Liberal of Bilbao go to Ezkioga, and there were no such eyewitness reports in the republican La Voz de Guipúzcoa .

The Basque newspapers covering the visions were those who had supported the winning coalition of candidates for Gipuzkoa in the Constituent Cortes, the parliament in Madrid that would draw up a constitution. La Constancia was the newspaper of the Carlists and Integrists; its deputy was Julio Urquijo. Two priests had recently founded El Día , the newspaper that reported the visions in greatest

detail. The Catholic press reprinted El Día 's stories throughout Spain. The newspaper was discreetly pro-Nationalist, with emphasis on news of the province of Gipuzkoa, and its deputy was the canon of Vitoria Antonio Pildain. The coalition candidates were selected in its offices. Euzkadi was the official organ of the Basque Nationalist Party, whose deputy was Jesús María de Leizaola. El Pueblo Vasco catered to the more worldly gentry of San Sebastián, and its deputy was its founder and owner, Rafael Picavea. The weekly Argia, which tended toward nationalism, went out to rural, Basque-speaking Gipuzkoa; it carried many reports on Ezkioga in 1931. News of the visions reached the public in these newspapers and their points of view affected the reporting. Even leftist newspapers depended on these sources.

While the newspapers reporting the visions were Catholic and broadly to the right, they did have some differences. The editor of La Constancia, Juan de Olazábal, was the national leader of the Integrists. In 1931 and 1932 this faction was in the process of rejoining the main Carlist party. The Integrists, "few but vociferous," had another organ in San Sebastián, the weekly La Cruz . The two factions were most powerful in Navarra, where they had two newspapers, the Carlist La Tradición Navarra and the Integrist El Pensamiento Navarro . In contrast to the readers of the Carlist and Integrist newspapers, the readers of Euzkadi, El Día , and Argia wanted an autonomous government that responded to the traditions, culture, and "race" of the Basques. For them the form of the Madrid government was immaterial, and they eventually allied themselves with the Republic and fought against the Carlists in the civil war of 1936–1939. But in 1931 the Basque Nationalist Party and the Carlists, the two main forces in the agricultural townships of the Goiherri and among the clergy of the diocese, stood together against the Republic. El Pueblo Vasco, whose Catholicism and Basque nationalism was somewhat more liberal, provided its readers with a more skeptical slant on the Ezkioga visions. While always respectful, its reporter occasionally pointed out inconsistencies and doubts. But in July 1931 its articles, some quite extensive, were largely factual.[18]

For the press see Cillán, Sociología electoral, 147-153, and Saiz, Triunfo; for Carlists and Integrists see Blinkhorn, Carlism and Crisis, 11 (quote), 46-67; for El Día especially interview with Pío Montoya, San Sebastián, 11 September 1983.

In July and early August 1931 the three San Sebastián Catholic daily newspapers each had an average of two articles daily on the visions, usually naming visionaries and describing what they had seen and heard. They also carried background articles on trances, levitation, and stigmata and on the German stigmatic Thérèse Neumann, the Italian stigmatic Padre Pio da Pietrelcina, and the visions at Lourdes, Fatima, and La Salette. Ezkioga was a big story; only the campaign for a Basque statute of autonomy surpassed it in column inches. These newspapers served as a filter. Some news passed, some did not.

Between the reporters and the seers there was another filter, that of an ad hoc commission of the two Ezkioga priests, Sinforoso Ibarguren and Juan Casares; a doctor from adjacent Zumarraga, Sabel Aranzadi; the Ezkioga health aide and the mayor and town secretary. The doctor examined those seers who came

forward, and the priests asked questions that they eventually made into a printed form. By the end of July 1931 the commission had listened to well over a hundred persons, and because many persons had visions on more than one night, the total number of visions they heard about in that month was somewhere between three and five hundred. They sometimes allowed reporters to hear the seers and copy the transcripts. The doctor guided them toward the most convincing cases. The members of the commission encouraged some visionaries to return after future visions but dismissed others. The press and the commission tended to ignore adult women seers and heed adult men, comely adolescents, and those children who expressed themselves well (see questionnaire in appendix).

The seers themselves also participated in the filtering; some of them reserved what they saw for themselves or their families and did not declare their visions. This self-censorship particularly applied to the content of the visions. Seers were especially unlikely to declare unorthodox visions. For instance, one woman told others privately of seeing something like a witch in the sky. And a man from Zumarraga told me he saw a headless figure. He added, "Don't write that down; we all saw things there."[19]

Teresa Michelena, Oiartzun, 29 March 1983, said another woman spoke to her about the witch in the sky.

Similarly, two girls about seven years old had visions of an irregular sort in Ormaiztegi in late August and early September 1931. The father of one of the girls, a furniture maker, wrote down what they saw. On August 31 the girls said that they saw a monkey by the stream near the workshop and that two days before in the same place they had seen a very ugly woman. They then saw the monkey turn into the same woman, whom they called a witch; the witch said she understood only Basque. Directed by the father, who saw nothing, they asked the witch in their imperfect Spanish why she had come and from where. She replied, in Basque syntax and Spanish vocabulary, that she had come from the seashore to kill them. Later she supposedly ran up to the workshop and tried to attack the religious images the father was restoring.

On September 1 the two children saw the witch in the stream with a girl in a low-cut dress, short skirt, painted face, and peroxided hair who said she was "Marichu, from San Sebastián, from La Concha [the central beach]." The father made the sign of the cross and the girl disappeared, leaving the old lady, who made a rough cross in response. Later, both appeared again, coming out of the water together. The next day the Virgin appeared to the children together with figures representing the devil and temptation. The girls also saw a procession of coffins of the village dead.

These visions are a mix of Basque folklore and contemporary religious motifs, with a dash of summer sin. "Marichu" was a kind of modern woman counter-image to the Daughters of Mary. The newspapers might never have reported the Ormaiztegi visions if the church had approved the apparitions of Ezkioga. The reporter did not reveal this unorthodox vision sequence until after the tide had turned against the apparitions in general.[20]

Easo, 17 October 1931; PV and LC, 18 October 1931; Rodríguez Ramos, Yo sé, 16-22.

Such journalistic suppression seems to have been common in July, when the visions had great public respectability. Starkie provides an example from the village of Ataun of the kind of vision the newspapers did not report:

I met a visionary of a more sinister kind who assured me with a wealth of detail that he had seen the Devil appear on the hill of Ezquioga … "I saw him appear above the trees—tall he was, with red hair, dressed in black, and he had long teeth like a wolf. I wanted to cry out with terror, but I made the sign of the Cross and the figure faded away slowly."[21]

S 129.

Even mere spectators were aware that what others were seeing might not be holy but instead devilry or witchcraft. The word they used, sorginkeriak , literally "witch-stuff," reflected the ambiguous attitude toward the ancient subject, for it also had a looser meaning of "stuff and nonsense." Many priests preached that women should be retirado (indoors) after 9 P.M. ; thus, the woman who appeared at night on the hill was de mal retiro and going against the priests, something the Virgin would not do. This widespread opinion, more common among men, was also an indirect criticism of the women who stayed out late praying on the hillside. As long as the visions were respectable in the summer of 1931, the press rarely put such criticism into print.[22]

Miguel Zulaika, Itziar, 18 August 1982; J. M. de Barandiarán, Ataun, 9 September 1983; and P. Dositeo Alday, Urretxu, 15 August 1982: all reported the argument in 1931 against the visions. Masmelene, EZ, 15 July 1931, and Larraitz, ED, 28 July 1931, made it in print. Masmelene was a student of Barandiarán, and Larraitz one of the founders of the pro-republican Acción Nacionalista Vasca.

A third kind of distortion or molding affected the orthodox visions when certain messages were emphasized over others. The allocation of attention was the business of every person who when to, talked about, or read about the visions. In a gradual collective selective process, the Catholics of the north focused on the messages they wanted to hear. We can follow this process day-to-day through the press.

The first visions of the first seers were of the Virgin (they had no doubt who it was) dressed as the Sorrowing Mother, the Dolorosa. The image appeared slightly above ground level, and the visions were at night. Sometimes the Virgin was happy, sometimes sad, but her emotions were the "content" of the visions. On July 4 others began having visions, and during the rest of July newspapers described over two hundred of the visions in which the Virgin's wishes became more explicit. Some visionaries told how the Virgin reacted to her surroundings, to the audience, or to the prayers. Some saw the Virgin as part of allegorical tableaux. Others saw her move her lips. And starting on July 7 still others heard her speak. Visions involving acts, such as cures or divine wounds, developed only in later months.[23]

LC, 7 July 1931; PV, 10 July 1931.

The rosary, a fixture of the gatherings, began on the third day of the visions. During and after the rosary the audience engaged in a kind of collective blind dialogue with the holy figure through the seers: on the one hand, the prayers and Basque hymns; on the other, the seers communicating the Virgin's emotions and attitudes. The Virgin was alternately sad, weeping, sad then happy when she heard the prayers, and happy. She sometimes participated in the prayers and

hymns, said good-bye, and even threw invisible flowers. Mute glances, reproachful looks, sweating, and an occasional smile had been the main—indeed the only—content of the miraculous movements of the crucifixes of Limpias and Piedramillera.

People also deduced Mary's emotions and mission from her dress, which was mainly that of a Dolorosa with a white robe and black cape (the commission took care to establish her apparel and how many stars there were in her crown), but sometimes she came as the Immaculate Conception, Our Lady of Aranzazu, Our Lady of the Rosary, or other avatars. Some seers saw one Mary after another in rapid succession.

The communication between the Virgin and the congregation was the central drama of the Ezkioga visions in the first month, but there were other vision motifs. Visions predicting a divine proof of the apparitions earned particular attention. From July 10 there were reports of an imminent miracle. Seers' predictions overlapped, so when one miracle did not occur, people's hopes shifted to another. A rumor circulated that a very holy nun—some said from Bilbao, others said from Pamplona—had predicted on her deathbed that in a corner of Gipuzkoa prodigious events would take place on July 12. On the day before that date the carpenter Francisco "Patxi" Goicoechea of Ataun had a vision in which the Virgin said that time would be up after seven days. People understood this statement variously to mean that the miracle would take place on the sixteenth or the eighteenth. On July 12 an article appeared in El Día drawing parallels between Ezkioga and Lourdes and raised hopes for a miracle in the form of a spectacular cure. On the fourteenth Patxi again referred to a time span (un turno ) elapsing, and an eleven-year-old boy from Urretxu heard the Virgin say that she would say what she wanted on the eighteenth. On the twelfth and sixteenth of July there were massive audiences of hopeful pilgrims. The newspapers reported hundreds of seers on the twelfth, but on neither day was there a miracle of any kind. On the seventeenth the Zumarraga parish priest told a reporter he would rather talk the next day: "Let us see if tomorrow, Saturday, the Virgin wants to work a miracle; perhaps something startling and supernatural, as at Lourdes, will be a revelation for us all. Maybe a spring will suddenly appear, or a great snowfall."[24]

All 1931: for nuns, La Tarde, ELB, and PV, 11 July; "Ormáiztegui," PV, 17 July; priest in PV, 18 July.

The Zumarraga priest's hopes in print set the stage for a day of record attendance on July 18, which the press estimated at eighty thousand persons. But the day before, Ramona Olazábal, age sixteen, was already setting up new expectations because the Virgin had told her that she would appear on the following days. No miracle occurred on the eighteenth. But Patxi heard the Virgin say she would work them in the future, and a girl heard her say that she would not show herself to everyone because people were bad; so hope for a miracle continued. On July 23 Ramona heard the Virgin affirm that she would work

miracles in the future; on the next day there was a story that another nun, this one living, had announced great events in 1931; and on the following day a servant girl from Ormaiztegi announced that the Virgin "wanted to do miracles."[25]

All 1931: seer, aged 16, ED, 18 July; predictions on the eighteenth, ED and PV, 19 July; Ramona, PV, 24 July; nun, LC, 24 July; servant, ED, 26 July.

When Starkie was in Ezkioga, around July 28, he found local people and outsiders in a kind of suspense, waiting for a sign. On July 30 the Virgin, ratifying what most persons had already concluded, declared through Ramona that "miracles were not appropriate yet."[26]

ED, 31 July 1931.

By then the seers had worn out their audience, which declined to a few thousand persons and on some days to a few hundred, until Ramona herself became the miracle in mid-October.