The Managerial Revolution

In discussions of the relationship between the corporate form and the stock exchange, probably no book has had the impact of Berle and Means's The Modern Corporation and Private Property (1932). Berle and Means argued that the rise of the large, diffusely held, professionally managed corporation fundamentally altered the nature of the relationship between ownership and control over the firm. They worried that in separating these two functions, organizational behemoths were created that were largely unaccountable to traditional property holders and would pursue their own interests at society's expense. Much of the work in organizational economics and business history over the past two decades has, implicitly or explicitly, been an attempt to address the Berle and Means thesis by providing an efficiency rationale for the managerial bureaucracy (e.g., Chandler, 1962, 1977; Williamson, 1975, 1985; Fama and Jensen, 1983). The reality of the management-ownership separation in the United States, however, is not itself in dispute among these writers.

And in Japan? On the one hand, there are far fewer publicly traded companies in Japan than in the United States and far more privately held firms. These private companies are very often smaller and owner-managed (Patrick and Rohlen, 1987), suggesting the kind of traditional capitalist enterprise that Berle and Means admired. As of 1987, there were more than 24,000 public corporations in the United States, in comparison with less than 2,000 in Japan. Since the number of firms listed on the New York and Tokyo stock exchanges was nearly identical (at 1,647 and 1,634, respectively), the big difference is in the prevalence of smaller, public U.S. firms traded over-the-counter and on smaller exchanges, and their near absence in Japan. Public listing in Japan is limited almost entirely to the oldest, most prestigious corporations. According to one study, nearly half of all public corporations in the United States went public within the first ten years of establishment, in comparison with under 1 percent in Japan.[12]

Among its largest corporations, on the other hand, Japan, like the United States, has progressed far down the road toward managerial capitalism. As of at least the mid-1970s, the ownership of shares in large corporations by their officers in both countries was negligible. Herman

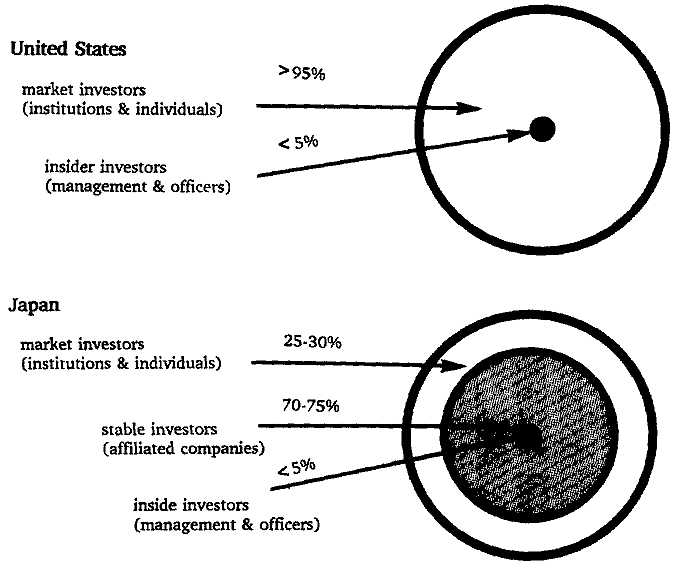

Fig. 2.1. Investor Composition in Large U.S. and Japanese Companies.

(1981) finds that in nearly two-thirds of the two hundred largest non-financial firms in the United States, directors owned less than 1 percent of the voting stock. Similarly, Okumura (1983) presents statistics showing that the holdings of corporate officials (directors and auditors) in Japanese firms of over ¥ 10 billion in assets (around $400 million at 1983 rates) averaged under 1 percent in 1976. In the United States, nearly all the remainder is controlled by independent individual and institutional investors, most often in small, fractional holdings. In Japan, in contrast, a substantial portion of the remainder is controlled by alliance partners, existing in a gray area somewhere between the polarities of Berle and Means's management-shareholder dichotomy. The differences between these two systems of corporate control are depicted schematically in Figure 2.1.

What does the existence of these distinctive capital relations mean for the interaction between ownership and management in Japan? One perspective that has been taken in financial monitoring models is that it improves the capability of shareholders to learn about and to discipline

management in otherwise diffusely held corporations (Jensen, 1989). As relatively coherent shareholder bodies, this argument goes, corporate alliances are able to mobilize collectively in cases of severe managerial malfeasance in order to protect shareholder interests. This is more difficult when shareholders are poorly organized, as in the United States. It should be pointed out, however, that shareholders in diffusely held U.S. corporations enjoy control mechanisms never anticipated by Berle and Means-and largely unused in Japan-including hostile takeovers and proxy contests.[13]

Two other implications are less obvious, but at least as significant. The improved managerial discipline function of corporate alliances noted in the previous paragraph continues to view the interests of affiliate-share-holders as identical to those of other shareholders-albeit, perhaps, with greater means of enforcement and better information. But affiliate-share-holders actually have plural interests. As companies' bank lenders and business partners, these investors are interested in a more complex set of goals than capital market returns. As two observers have pointed out:

Unlike Western institutional shareholders, which invest largely for dividends and capital appreciation, Japanese institutional shareholders tend to be the company's business partners and associates; shareholding is the mere expression of their relationship, not the relationship itself. [Clark, 1979, p. 86.]

In most listed companies in Japan, a sizable portion of the stock remains permanently in "safe" hands, thus assuring continued control by management. Shareholdings are fragmented between "insiders" and "outsiders." Insiders are small circles of executives and financiers often connected with the issuer's enterprise group. . .. The insiders are in charge, not by virtue of their positions, but as a product of the multiplicity of their roles in the firm; they are creditors, shareholders, lifetime employees, management and business partners. [Heftel, 1983, p. 165.]

Moreover, they often have their own shares held reciprocally and in complex networks of shareholding among other affiliated enterprises. Companies whose shareholding bodies are dominated by affiliate-shareholders will, quite rationally, consider the interests of alliance partners first before those of independent shareholders when making investment decisions.

In addition to redefining the constraints placed on the Japanese firm, the predominance of affiliate-shareholders also shapes the character of Japanese stock markets. This is not so much through modifications in the basic regulations and rules of operation, for these are similar in most formal respects to those in the United States and elsewhere (although

actual functioning differs in several important respects, discussed later). Rather, it is through changes in the dominant players in the market. In both the United States and Japan, an "investor revolution" marked by the rise of large-scale investors has taken place that in many ways is as important to the understanding of twentieth-century capitalist enterprise as the managerial revolution identified by Befit and Means. But whereas the managerial revolution has followed relatively similar trajectories across all advanced economies in the broad sense that corporate decision making moved into the hands of nonowning managers, the investor revolution has not.