9

Death and the End of Time

Final Exchanges

This is the day that the hands separate

And the feet step apart

One of us going off to dig the gardens and weed the grass

The other to rest in the tombs in a row, the graves in a line

—From a Kodi death song

Death represents the end of one strand of time, the time that an individual spends on this earth, and the adjustment of several other strands, which have become entangled in the time span of personal biography. A funeral provides a final accounting of temporal relationships and a reckoning of exchange obligations. It is the occasion on which the different temporal values of affinal and agnatic ties are made visible. Affinal ties stretch horizontally through Kodi society, binding a man to his wife-givers and his mother's village of birth. The affines are the "givers of life" and remain able to bestow health, fertility, and descendants on their wife-takers. At death, conflicts with them must be resolved so the pollution of the corpse can be removed from the village and the soul can be reclaimed by the patriline. Agnatic ties, in contrast, are traced vertically, up and down the time line of descent. They endure even after the dissolution of the physical body and may be expressed as promises or infractions from the past carried forward onto future generations.

Death rites require a final separation of affinal and agnatic ties, as the deceased is separated from the living and incorporated into the community of the marapu . At the funeral, the authority of the dead person is reclaimed and redistributed by his or her descendants. Silent exchanges with affines and extended verbal negotiations with agnates mark the contrast in temporal modes: the ties of affinity are vital but perishable, while those of agnation are frozen but enduring. A married woman's funeral is held

in her husband's village, the final act in the exchange drama that brought her there. A man's funeral is held in his own ancestral home and can reach far into his past. As the dead man takes leave of his family and their affairs are put in order, his descendants must journey back through the generations to understand the reasons for his death. The mystery is probed, suspects are interrogated, and when the angry spirits are found they are placated with gifts and promises. The living bargain with their own ancestors for a bit more time to fulfill their obligations, asking for the blessings of health and long life to hold the promised rituals. Their solutions are personal, not philosophical, but they reveal the private strategies that unravel around predetermined sequences. The predetermined sequence of a funeral must encompass the idiosyncrasies of an individual biography. In studying a single funeral, we see how at times these sequences may themselves be changed, or reabsorbed, into longer-term phases of the life cycles of houses, villages, and clans.

The process begins with the separation of death and the efforts to interpret its meaning for the living.

Mortality as a Break in Time

The news of Ra Honggoro's death broke just as the mounted ritualized combat of the pasola finished. Throngs of elaborately costumed riders, their heads bound with red and orange cloth, their horses decorated with bells and streamers, rode back from the grassy field near the beach along the line of ancestral villages. As they passed in front of Malandi, the taunts of greeting and shouted replies mixed with wails of mourning, and even casual passersby realized what the news must be.

Ra Honggoro was a wealthy and prominent man, who had already dragged a large megalith for his own grave and placed it along the path that the riders and spectators would follow as they returned from the pasola . Three years before, he had sponsored a large feast to consecrate the stone, and hundreds of pigs and several dozen buffalo were sacrificed. In recent months, realizing his illness was serious, he had left behind his garden hamlet and the wide pasturelands where his herd of over a hundred animals grazed to return to Malandi. Moving into the lineage house he had built at another feast some eight years before, he lived close to the graves of his own father and grandfather with his second wife and the three youngest of eleven children. When relatives came to scatter betel on the tombs of their ancestors, he was already too weak to get up to receive them, and the chickens roasted in the morning to read the portents of the new year bore red flecks of danger on their entrails.

He had been a vigorous, powerfully built man who did not surrender easily to fatigue or adversity. When he sponsored his first major feast in the gardens, he had chosen a name for his horse and dog that epitomized the destiny he wanted to fulfill:[1] His horse was Ndara Njamagha'a, "the horse that is never satisified," and his dog Bangga Njamanukona, "the dog that shows no reluctance." He saw himself as a fighter, a man who had built up his own fortune and pursued his goals with energy and persistence. The tenacity with which he amassed his wealth had lasted through several major illnesses. But finally, at the age of about fifty, he succumbed to gout and kidney failure, just as others were celebrating the rite of regional renewal.

His widow and daughters were the first to shed tears over his body and stroke it with their hands. The dirges they sang were full of bitter accusations, for Ra Honggoro's death betrayed the very qualities he had identified as his own. "How could you leave us like this, father," wailed his oldest daughter, "you as proud as a noble parrot, you as strong as the lordly cockatoo? How could you go off on your own journey when we are left alone without you ?" "What made you slip this time, what caused you to fall into the trap?" his widow wailed, "when so many times you came back to us, when so often your strength returned?"

Women monopolized the early stages of mourning, clustering around the corpse as it lay on the front veranda, at the point marked for transitions inside and outside the house. They reproached the dead man, accusing him of callousness, of a selfish separation from those who loved him, of disregarding their needs and their dependency on him. Through "the flowing of mucus and the shedding of tears" the living exorcise their feelings of loneliness and betrayal, performing a public drama of hysterical grief and sorrow.

The elaborate display of emotion was directed more to the human audience of funeral guests than to the invisible one of the spirits. The dead man himself never hears these reproaches; his soul sits with the family on the veranda and shares its meals, but remains unconscious until four days after he has been buried. Only then are the lines of communication between the dead and the living reopened, but on different terms, for now the unconscious ghost wakes to discover he has been remade as an ancestor.

[1] All prominent Kodi men (as well as some women) have horse and dog names, which can be used in polite speech to signify their renown. Some of these names are inherited, usually from a famous grandfather. Others can be chosen by the individual in question to stress a part of his own biography—his achievements or hardships encountered. Hoskins 1989a discusses the horse and dog names of one prominent Sumbanese man and several of his wives.

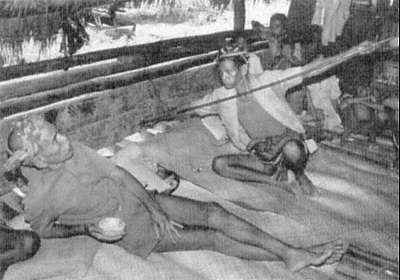

Ra Honggoro's body is attended by his mother, seated in the upper left of

the picture, with her hair loosened in mourning, while his widow and

daughters, to the right, caress the shroud and sing of their anger and

despair. 1988. Photograph by Laura Whitney.

Visible and Invisible Participants

The movement a person makes from sharing the lives of the living to becoming part of the invisible community of the marapu defines the particular intimacy and ambivalence that characterizes relations with spirits of the dead. Other invisible beings—the marapu who guard the house and village; the spirits of wealth objects, fertility, or garden crops—are addressed and propitiated in Kodi rites, but they have never "crossed over" from the human side and do not have human shapes, personalities, or characteristics. The spirits of the dead, however, retain many human attributes and are nostalgic and jealous of the time when they lived among their descendants. They constantly strive to converse with the living, to reestablish a casual give-and-take in conversation, to return to the reciprocity and equality they enjoyed in their lifetimes. Communications with the dead oscillate between efforts to achieve contact on the basis of common experience and substance, on the one hand, and efforts to keep them at a distance, on the other. The residues of personal memory are plumbed and exhausted in the work of mourning, to achieve a new control over communication with the dead, channeling it away from personal contact

into the formal interchange of blessings and obedience to ancestral law. The envy and resentment the dead feel because of their exile from the world of the living has to be transformed into passive resignation, a willingness to serve as an arbiter of tradition rather than a personal advocate.

The spirits of the dead suffer feelings of estrangement, a yearning for renewed closeness with their families. When they try to move closer, the rituals of death send them away: The dead person is moved from the category of one who speaks as a kinsman, a person with individual attachments and loyalties, to one who acts as an ancestor, the detached voice of collective law, who protects and sustains his descendants with impartial wisdom.

Ra Honggoro's funeral displayed the two processes that operate to turn the conversation mode (appropriate to relations with the living) into a mode of ritual exchange (appropriate to relations between the living and dead). The first process, entrusted to affines (relatives from the dead man's village of origin), concentrated on separating the physical substances of the living and dead, by removing the pollution of death that had settled on the house where the corpse lay in state. The second, entrusted to his agnates, was achieved through sacrifices, oratory, and divination. It brought about the transformation of the dead person into a marapu , by summoning the invisible community of ancestral spirits and discovering the cause of his death.

Both processes are concerned with exorcising dangers associated with death, but whereas the first deals with dangers arising from earlier closeness and identification with the dead man, the second identifies the dead man in a collective, legal sense as a member of a specific lineage and the inheritor of debts and obligations. The pollution removed by the affines is the pollution generated by the conflicting web of affinal relations, which bound Ra Honggoro to Bondo Maliti, the village of his mother's birth and the "source of his own life" in Kodi exchange theory. Death and funeral exchanges are the last act in a long affinal drama begun when his mother first married into Malandi. Livestock and gold were presented to her parents to secure the right to claim children as members of the Malandi ancestral community. The wife-givers communicated their assent at that time with gifts of pigs and cloth. Half a century later, they now come to receive the heads of sacrificial animals, the final gift that marks the end of the cycle. Once this last debt has been paid, they renounce any further claims on the soul of the dead man, and he can be fully integrated into the village of his patrilineal ancestors.

The two parts of the process thus end the obligations of affinity even

as they reassert the enduring ties of agnation, reconstituting the dead person as an ancestor. The living are bound by many complex and ambiguous exchange ties. In the ceremonies of death, some of these binding ties are loosened, while the force of others is made more salient. As the corpse itself decomposes for the three or four days that it lies on the veranda, the person, too, is decomposed into different kinds of constitutive relationships. Some are sloughed off as the flesh separates from the bones; Others are preserved as enduring and permanent parts of his name and reputation.

Affinity and agnation are contrasted as vitality and immortality, perishable and imperishable, silence and speech. Wife-givers present gifts of cooked meat, cloth, and rice in the inarticulate expression of grief, shared substance, and loss. Lineage descendants and wife-takers bring live animals, gold, and money, gifts to help in reconstituting the house and its members. Once the exchanges are completed, the affines return home, but the agnates remain gathered in the house to investigate the causes of the person's death. The divination is framed as an interrogation of the past. Several generations of family history are combed through as the participants search for sources of disagreement or neglect of ceremonial obligations, discovering points of weakness within the lineage. Working at first from ignorance, gradually supplemented by testimony from the audience of family and relatives, the diviner spins elaborate verbal nets of possibility and speculation, hoping to catch the killer in these nets and confirm the result with spear and chicken divination.

Affinal exchanges involving food and the personal effects of the dead disarticulate and dissolve the dead man's earlier unity, his physical body, into separate parts. Agnatic negotiations with the spirits, in contrast, articulate and construct a shared version of collective history. This interpretation, distilled from memories scattered through many individual minds, is then linked to a future plan of action. Death is the end of one kind of time, that of a person's vital involvement in ongoing exchange, but the beginning of another, that embracing the collective traditions of the lineage. The diviner and his audience gradually shift from speaking to a husband, father, or brother and begin a ritually mediated interchange with a marapu . The personal life history is revised to become part of the li marapu , the ancestral invocation that binds the collectivity to its past.

Making Peace with the Wife-Givers

The death of an important man immediately mobilizes his network of affinal relatives as messengers are sent out to announce the event to all those who must bring contributions to the funeral. In the case of Ra

Honggoro, his wife and mother quickly began to bathe the body, binding his knees close against the torso, folding the hands on the chest, and resting him on the right side as a sign that his death was a peaceful one. At the same time, his sons and brothers rode off to summon parties of mourners, who converged on Malandi bearing fine textiles for the many-layered shroud. All those who had given wives to Malandi brought pigs, for a total of twelve; those who had taken wives brought six horses and five buffalo.

Drums and gongs were beaten continuously in front of the house of mourning. Each approaching party was greeted by male and female dancers—the men charging toward them with spears, then retreating after a brief display of anger, the women fluttering their arms gently and beating the ground rhythmically with their feet. The greatest anticipation, mixed somewhat with dread, concerned the arrival of Rangga Raya, Ra Honggoro's brother-in-law, who had also for the last three years been his sworn enemy.

The trouble between the two men stemmed from differences in exchange expectations. Ra Honggoro had twice paid bridewealth to Rangga Raya: some thirty-five years earlier for his first wife, Pati Kyaka, who died after bearing him five children; and again ten years ago for her younger sister, Gheru Winye, the mother of six more. Their brother had insisted on repeating the alliance by replacing one sister with another because he did not want a strange woman to raise his nephews and nieces. As a wife-giver twice over, Rangga Raya was expected to be generous with his sisters' children. Nevertheless, when Ra Honggoro's eldest son, Tonggo Radu, wanted contributions to his own bridewealth, his mother's brother said he had nothing to spare. Angry, the boy went secretly to his corral and took a large buffalo without permission. He called it borrowing; Rangga Raya called it stealing. The case was resolved through traditional litigation, and Ra Honggoro agreed to pay a fine of ten buffalo, only five of which had been presented by the time of his death. The two had not spoken or visited each other since these events.

Funerals are occasions for burying resentments and certain debts as well as collecting on others. After years of furious rhetoric, Rangga Raya came back into Malandi leading not simply the large pig expected of an important wife-giver, but also a buffalo bull. The bull was offered as a wawi njende , something "to stand for a pig,' and, in fact, also for much more, because this disproportionately large gift was presented as the "branch of white millet, the strands of yellow beans" (kalangga langa kaka, kategho kembe rara )—a peace offering extended to end the dispute.

As soon as his party was seen on the road, the drums beat faster and

people thronged near the entrance to watch an emotional scene of reconciliation. Rangga Raya walked up into the house of mourning holding a fine man's cloth, which he placed on his brother-in-law's body, sobbing profusely. Then he turned to embrace the widow, his younger sister, and finally even Tonggo Radu, the accused thief. He stood beside the body on the front veranda and made a tearful plea for forgiveness to all present:

We hadn't yet sheathed the knife | Nja pango mija la maloho oronaka ha |

We hadn't yet cut the rope of our | Nja pango ropo la kalembe oronaka |

So we didn't drink water together | Mono inde pa inundi weiyo |

So we didn't eat rice together | Mono inde pa mundi ngagha |

But now let it all go | Henene tanaka |

Under the cool shady leaves | Laiyo ela ndimu ndaha rouna |

Beside the fruit of the ironwood tree | Laiyo ela komi njaha wuna |

In banishing the reasons for the quarrel, he reopened the path of visits, credits, and loans between affines.

The reconciliation was necessary not only for social reasons but also for a ritual one. Because the grave of Pati Kyaka had to be opened in order to place her husband beside her, an additional sacrifice was required to serve as "hot water" (wei mbyanoho ), a libation poured on her grave to allow it to be opened and refilled. Rangga Raya was the only one who could remove the pollution of death from this opened grave by receiving the head of the sacrificial buffalo. Without his participation, the ghost of his sister could not travel with her husband to the afterworld, but instead would remain restless and likely to trouble both households.

Returning Life to the Origin Village

Ra Honggoro's own life was owed to the village of his mother's birth, Bondo Maliti, which had served as the "steps and doorway" (lete binye ) through which she traveled to come to Malandi to marry his father. While relations with his wife-givers had been intense and conflict-ridden, the ties to Bondo Maliti were "cool"—without struggle, but also without much contact over the past fifty years. Still, those villagers remained the only ones who could reclaim his most personal possessions (his betel pouch, his plate, and his drinking gourd), place his body in the grave, and take the life of his favorite riding horse.

The Bondo Maliti contingent did not arrive until the third day after his

death. They had wanted to delay their entrance until they had been joined by family members who lived in the eastern part of the island, but were finally persuaded to come by Ra Honggoro's sons, who feared the body would not last another day in the intense heat. About fifteen people from Bondo Maliti marched in with a long-tusked pig on a litter covered by a fine cloth, led by Ra Honggoro's cross-cousin and the present headman of the township. Each person brought a fine textile to place on the corpse, along with tears and laments. Another man's cloth was draped over the neck of the Horse That Is Never Satisfied, which was tied under the house just below his master's body so that Ra Honggoro's soul could ride on his own horse in the procession to the tomb.

After they had been seated in the house and served a meal, preparations were made to move the body. Some younger members of the Bondo Maliti contingent were sent to open up the stone tomb and wrap the bones of Pati Kyaka in new sarungs to prepare her to receive her husband. Ra Honggoro's eldest son stepped up to mount his father's horse, leading the procession from the ancestral village to the tomb. His brothers and agnates went into the house to lift up the body and carry it, bound in a shroud of many layers of textiles, to its final resting place.

The moment the corpse was moved from the house provoked a great display of emotion from the women who had been guarding it and singing to it for the past three days. As other arms started to lift it up, they resisted violently, wailing and shrieking, desperately caressing the bundle of cloth one last time before it left. The men at this time were grim and determined, showing little feeling as they lifted the bundle onto their shoulders and walked after the horse out the village gates and toward the stone grave, followed by several hundred distraught mourners.

Members of the origin village received the body at the tomb, placing it inside the chamber along with many other textiles and gold omega-shaped ear pendants (hamoli ryara ). The gold was given as "tears from the house" so that other rnarapu in the land of the dead would know that he was an important person. As Ra Honggoro was arranged in the grave, the Horse That Is Never Satisfied galloped four times around the tomb; the steed was then led to the representative of the deceased's mother's brother's house. Holding on to the bridle, the mother's brother struck at the neck three times with a bush knife, thus displaying his right to take the horse's life, but then choosing to spare it.[2] A younger man in the party mounted

[2] The sacrifice of the dead man's horse is a convention of Sumbanese funerals that is nowadays only rarely observed. In the past, it is said that the horse was always killed to accompany his master on a voyage to the afterworld. At royal funerals in East Sumba, this is still often done, but increasingly the people of Kodi and

other districts in the west may choose to surrender the horse to the mother's brother alive. In the present case, the people of Bondo Maliti who received the horse said they spared its life "so that its master's name would not be forgotten and would be repeated by anyone who saw his horse." Even after its purification, a named horse cannot return to its master's house or village under any circumstances.

the horse and rode it triumphantly up and down the field before the gathered spectators.

As groups of sobbing women headed back to Malandi the horse was ridden to Bondo Maliti where a special ceremony was performed to bring its soul back from the journey into death. Water from a sacred source was placed in a wooden plate and circled over the horse's head four times to the left, then a kambukelo leaf was used to sprinkle several drops on the horse's forehead. This rite was designed to separate Ra Honggoro's soul from the horse and end his attachment to it, so he would not be jealous of its new master and cause the horse to sicken, fall, or be stolen. The circling was then repeated to the right, to fix the hamaghu or life force at the forelock. Members of the mother's brother's contingent now returned to Malandi to receive a ritual payment of a bush knife and spear (kioto bilu, nambu mbani ), presented on a plate with betel and a small amount of money, in payment for serving as the "counterpart to bury the dead" (nggaba pa tanongo ).

The funeral sacrifice (kaparaho ) must be performed in front of the dead man's house by members of his origin village or their representatives. Ra Honggoro's mother's brother from Bondo Maliti struck three times at the neck of the first sacrificial bull, then handed the bush knife over to another wife-giver to finish the slaughter. Government regulation limited the total to five large animals: three bulls and two large cows past reproductive age. The animals' livers were inspected to confirm that Ra Honggoro's soul had left on its journey to the afterworld, and their bodies were cut in half latitudinally, separating the head and front legs from the rear quarters.

This division of sacrificial meat is done only at funerals; it represents the separation of the dead man's body into the maternal contribution (the "life" received from affines), which must be returned to the origin village, and the paternal contribution, which remains in his village and is divided among the guests. The front part of the buffalo's body is strongly tabooed for all agnates of the deceased—not just members of his house, but everyone in his ancestral village. Any agnate who took a bite of this meat would be "eating his own brother;' consuming flesh that was part of his own substance, and certain to die from the poison of self-cannibalism.

The heads and front sections of the buffalo were presented to the people of Bondo Maliti, but they asked that a pig also be killed and divided

horizontally to accompany the spear and knife that they used to open up the dead man's tomb. No pig was available, so a young colt was presented to replace the pig and "lighten the burden" of those who had to return home carrying the pollution of death. The mother's brother's contingent came back with five half-carcasses; the meat from the body was divided among all the members of Bondo Maliti, but that of the heads was set aside, dried, and salted for a special rite to be held four days later.

The Final Time of Separation

As the guests returned home with their bloody burdens, the village of Malandi ceased activity for several days. Only close family members remained in the house of mourning, where the soul of the dead man lingered, still unconscious of the fact of his death. The spot where his corpse had lain in state was guarded by an older female mourner (tou kalalu ), in this case his mother, who followed a series of taboos that identified her with the corpse.[3] From the time of his death, she remained confined within the house, her hair loose and disheveled, unable to bathe or go out in the sunlight—in fact, almost completely immobile. She was also forbidden to hold on to burning logs or a knife, or to come in contact with anything hot or sharp. She took the place, in effect, of Ra Honggoro's own consciousness: her release from these restrictions would not come until he became aware of his fate, turning into an ancestor instead of a human being.

For four nights after the burial, Ra Honggoro continued to receive a serving of food at each family meal. His plate and cup remained at their usual places, and family members spoke to him casually, as his ghost was believed to stay among the living until the final rite. On the evening of

[3] The mourner is the most senior person among those women who have married into the house. Thus, the role can be filled by a man's mother, widow, brother's wife, or daughter-in-law, but may in no case be taken by a daughter, sister, or grandchild. A woman may be mourned by her mother, married sisters or daughters, and daughter-in-law, but not by an unmarried daughter, sister, or grandchild. No woman can mourn someone still in the same agnatic group as the one into which she was born. The mourner's main qualification is the previous experience of being transferred: like the dead soul, she has also undergone a transition from one world (the house into which she was born) to another (her husband's house, where she was moved at marriage). Both immersion in death and purification from its pollution are associated with the affinal relationship, a formulation often noted in Eastern Indonesia (Traube 1981; G. Forth 1981). The specific symbolic links that cause the Kodi to argue that "dead souls are like brides" are further explored in Hoskins 1987.

the fourth day, a small bamboo platform was erected in the bush just outside the village, and the "counterparts to bury the dead" from Bondo Maliti came back to Malandi to weave small baskets of coconut leaves and rice (kahumbu ) for the last meal fed to the soul of the dead man. The four first baskets made, marked with a long leaf-stem, were the sacred ones reserved for Ra Honggoro's ghost. They had to be boiled in absolute silence in the wee hours of the night. Others, distributed to kinsmen and affines, were boiled afterward and hung in the right front corner of the house.

At dawn, the widow and her children took the rice baskets, two pouches of rice, four ears of corn, and a bit of mashed banana to the platform outside the village. Two daughters waited to keep watch until a bird came to come nibble at them, a signal that the dead man's soul was ready to be sent away.

Ra Honggoro's soul realized he was dead at that moment. His daughters said they walked quietly back beside his stone tomb and overheard sobs, very faintly, from within the tomb: "We knew that father was singing his own funeral dirge." They bore the news to Malandi, and all the houses in the ancestral village began to bring contributions of rice and other foodstuffs for his final meal. Funeral gifts were redistributed to reciprocate those individuals who had been generous to the house of the dead man: textiles were given to those who brought horses or buffalo, and livestock were given to two of the wife-givers, who brought impressive pigs.

A pig was speared and divided latitudinally to receive the guests: the front part went to the "counterparts to bury the dead," the rear to the other guests and members of Ra Honggoro's own clan. Two plates, one sacred and one profane (tobo hari, tobo kaba ), were brought down to the lower veranda and offered to the mother's brother, along with the dead man's own plate, glass, spoon, and drinking gourd and the cooking vessel used to boil rice baskets for the final meal. A chicken was sacrificed to check that his soul was ready to leave. No food was served to him on the plate this time. Instead, shares of rice, chicken, and pork were placed on a kambukelo leaf (the same kind used for the blessing of the sacrificial horse), the marker of a transaction conducted with him no longer as a member of his house and village but as part of the invisible community of the marapu .

Silently, the mother's brother beckoned to the female mourner to come down out of the house and seat herself before him on the veranda. She came down, first covering her head with a folded textile to shield it from the sun's rays. He dipped the kambukelo leaf in the water used to separate off the dead soul and dabbed a bit of it on her forehead, calling back her

own soul from its long journey into the land of the dead. He pushed the textile off her head and gathered her long, unruly locks in his hands, helping her to bind them again in a knot and prepare for her ritual bath.

Shares of cooked food, raw pork, and cloth were then distributed among the guests, wife-givers, and wife-takers, who returned home with sections of the appropriate half of the sacrificed pig. The "counterparts to bury the dead" brought the dead man's plate, glass, cooking vessel, and spoon back to his origin village, where they were cast off to the west to follow him into the afterworld. Then a special meal was prepared of the tongues and the meat taken from the buffalo heads, which was eaten by those who had removed the pollution of death. From then on, Malandi and Bondo Maliti could continue to "give and take back the life" that was transferred through marriage alliances. This funeral marked the end of one series of affinal obligations, but it also reopened the path for new exchanges; because the proper sequences had been followed, the way was not blocked by the personal resentments of a still-too-human ghost.

The Meaning of Final Exchanges

Affinal exchanges are conducted almost as a pantomime: with few words, a transfer of substances and perishables is carried out to neutralize the dangerous contamination that the living experience in proximity to the dead. Women mediate between the living and the dead; their identification with the dead reveals a "feminization" of the dead soul itself, made passive and compliant for its transfer to the afterworld (Hoskins 1987a). In the words of the funeral dirges, women mourn their dead by recalling the feelings of detachment and separation that they experienced as brides, transferred to another house and village. The funeral is the time when obligations to maternal relatives must be remembered, because only members of the origin village can remove the pollution of death and cleanse the house of the filth that collects around the rotting body.

Ra Honggoro's funeral did, however, reveal many of the tensions and conflicts that can arise among affines as exchange obligations become the subject of disputes and litigation. The dissolution of affinity divides the dead person into that portion which was contributed by his mother's blood and the protective power of her relatives, and the portion that will remain within the patriline, elevated to the status of an ancestor. And after the silent transactions of the initial funeral, this second stage requires an extended verbal interrogation.

The Divination: A Journey into the Past

A funeral divination has much of the suspense of a detective story, as a whole array of spirit "suspects" are summoned down to the mat where rice is scattered, then sequentially interrogated as to their possible motives for withdrawing protection from the dead man. The real killer might be an ancestor, a guardian deity of the village or garden hamlet, or a wild spirit-companion who has been inadequately compensated for her gifts of wealth.

A week after Ra Honggoro's funeral, two diviners came to the house of mourning to begin a several-hour-long investigation of the causes of his death. The older one, Rangga Pinja, was a blind orator from a neighboring village who scattered rice and spoke the invocations to each of the spirit suspects. His younger assistant, Rendi Banda Lora, held the divination spear outstretched in his arms—the handle grasped by the left hand, the right arm traveling the length of the spear with the right thumb extended beyond the point. As the diviner presented questions to the marapu , his assistant lunged toward the wall of the sacred right front corner (mata marapu ) where the spirits were believed to come down. When his thumb touched the wall, the spirit's answer was positive, and he murmured his assent; when it fell short, the answer was negative, and he called back "Aree!" to his companion, a signal that the interrogation must continue.

The first spirit summoned was the spirit of the divination spear—mone haghu, mone urato ("the Savunese man, the divining man"), a magical object imported to Sumba from the small island of Savu and used as an intermediary to contact the other marapu . The spear probes the anger of the invisible ones, its sharpened tip cutting through their reluctance to reveal the truth or falsity of the diviner's speculative scenarios. As soon as the spear holder had confirmed that the spear's invisible spirit was present, the diviner began to "bring down the monkeys"—that is, to call on all the marapu who may have had reason to be upset:

From your throats and your livers | Wali kyoko wali y'ate |

From your backs and your bellies | Wali kabendo wali kyambu |

We bring you our language and | Mai dukinggumi paneghe patera |

To ask you about a person | Tana pa kalirongo a toyo |

Who was entered by death | Na tamaka a mate |

Whose disappearance arrived | Na dukingo a heda |

What was the anger and the | Ngge nikya a mbani a mbuha |

Which caused his death? | Na pa orongo a mate? |

Was there something skipped like a | Ba nei jo kingo a katadi hambule la |

Was there something missed like a | Ba nei jo kingo pa letengo la boki |

Metaphors for the vulnerability of the person use the idiom of the vulnerability of the house, which was so weakened by the intrusion of death that the final divination is described as a rite "to mend the walls and close the gap in the bamboo slats" (wolo handa, todi byoki ) where danger first came in.

The diviner's search moved through space, from the house and ancestral village where the funeral was held, to the various smaller settlements where the people of Malandi cultivated their gardens and the pasturelands for Ra Honggoro's extensive herds and unfinished stone house. Early hints suggested that the scene of the crime lay in distant garden lands, where one of Ra Honggoro's direct predecessors had made a promise to the marapu which was not fulfilled. A positive response was obtained for this first, exploratory suggestion of the reasons for his death:

Great was the wrongdoing of Raya | Bokolo pa ngandi Ryaya |

That he didn't heed the speech of the | Nja la tanihyada ha paneghe ndewa |

Short was the life of Raya | Pandako pa deke Raya |

That he didn't set aside the words of | Nja awa ta bandalango liyo ndewa |

The questioning now returned to the genealogical line, since the spirits of Ra Honggoro's father, Tonggo Radu, and grandfather, Maha Rehi, seemed most directly involved. Both, however, refused to come down when summoned. The diviner protested this recalcitrance by reporting it to the higher deities:

Stepping with their feet | Pangga ha witti |

They wouldn't step with their feet | Nja pangga ha witti |

So a dam came to block our speech | Pa kawata kori lyoko a paneghe |

Raising their buttocks | Kede ha kere |

They wouldn't raise their buttocks | Njaha kede ha kere |

The flow of water stopped for our | Pa hanamba nimbia weiyo a patera |

They won't cross their legs on the | Njana mbara mbica witti la nopo |

They won't fold their hands by the | Njana hangga hara limya la wiha |

Exasperated that his spirit intermediaries did not produce the needed witnesses, the diviner himself stepped back and allowed his assistant to begin a new series of questions, insisting again on the distress of the living and their need to establish an answer.

The younger man threw himself into the fray with great speed and vigor, invoking the deities that oversee divination within the house and can constrain reluctant ancestors to appear:

The loincloth must be unfolded, I say | Pa kawakaho kalambo wenggu |

The basket must be opened, I say | Pa bunggero kapepe wenggu |

I speak from the trunk of mother | Yayo wali pola inya da |

No more chasing lost horses | Tana ambu kandaba ndara mbunga |

I speak from the building of father | Yayo wall dari bapa |

No more straining the throat in vain | Tana ambu koko wei kaweda |

Something made the throat close in | Nengyo diyo pa wolo hudu koko |

Something made the liver tight with | Nengyo diyo pa rawi reka ate |

A reason the pig fell in the hunter's | Uru pa nengyo pokato wawi kalola |

A reason the horse tripped on the | Uru pa nengyo ndara nduka nambi |

Finally he succeeded in contacting the spirits of two resentful ancestors who agreed to come down to answer the questions of the older diviner. He then stepped back and allowed his superior to continue the questioning.

Rangga Pinja established that the trouble came from Lolo Peka, Ra Honggoro's pasturelands in the distant region of Balaghar, where he had made a pact with a wild spirit that was not fulfilled. Once he verified the role of the wild spirit (the one "close as the pouches of a betel bag, the folds of the waist cloth" ndepeto kaleku, hanguto kalambo ), he broke out of the ritualized dialogue with the spirits to ask his human audience to supply some of the missing details. "Who was this secret spirit-wife of Ra Honggoro's?" he asked them. "Has anyone seen her? Is she the same as his grandfather's secret consort?"

Relatives from the pasturelands in Balaghar remembered that they had heard stories of a tall beauty from the sea who had formed a pact with one of Ra Honggoro's ancestors. Others said they had seen her from a distance near his buffalo, or wandering off into the forest with him. She could take the form of a megapode, a wild forest hen with long legs who lays very large eggs. The megapode is a prodigal of fertility and productivity, but she is a bad mother: she builds elaborate mud nests for her eggs, regulating the temperature for incubation by means of elaborate tunnels, but then leaves her young to hatch on their own. Megapode fledglings are born as orphans, deserted by their mother, and forced to make their lives on their own.

The megapode bird represents reproduction without nurturance, fertility without feeling, and is associated with the rapid growth of wealth and descendants but improper care. In the same way, a wild spirit-wife may give riches, but in return she saps the life of her human consorts, or demands sacrifices of them and their children. Ra Honggoro had earlier promised to offer a long-tusked pig and a buffalo with elbow-length horns to the wild spirit when he gave a feast in the gardens, a vow he had neglected to carry out. As a consequence, his spirit consort began to weaken him until he agreed to comply with her wishes.

She broke apart the bridge leading | Na mbata nikya a lara lende loko |

She extinguished the flames of the | Na mbada nikya a api hulu mara |

She shortened his life using the same magical power that had earlier increased the fertility of his herds and added to the splendor of his feasts. Through the image of the neglected wild bird-woman, Ra Honggoro was presented as a victim of his own careless pride.

The divination revealed, however, that the wild spirit did not do her work alone. She had accomplices among the guardian spirits of the hamlet, who also felt that a debt to them had not been repaid. To probe the reasons for this discontent, Rangga Pinja once again opened up the floor to the human audience, who told him stories of illnesses and deaths in the garden hamlets that they suspected were part of the same complex of guilt.

Because no one knew why the spirits wanted them to feel guilty, the diviner asked for two chickens to use in intermediate offerings. The first. was dedicated to the spirit of the divination spear, to confirm that they were still moving in the right direction ("toward the tail of the bay horse, toward the base of the knife's sheath"). The second was dedicated to the

Lord of the Land, the angry garden spirit, who was promised a sacrifice for renewed fertility once the mystery of the death was solved.

The signs in the chickens' entrails were positive, so the questioning continued. The diviner traced the locus of discontent to the settlement at Homba Rica, where the problem seemed to concern rice spirits that had been displaced without ever having been properly restored. "Did rice fields burn in this area? Were there ceremonies to call back their souls?" he asked his audience.

Yes, he was told, paddy had once burned on the stalk—some fifty years ago—and the souls had been called back by Maha Rehi, Ra Honggoro's grandfather. But one old man remembered that once the spirits had been called back, the villagers should have held a singing ceremony (yaigho ) before planting to bring the lost rice souls inside the gates of the hamlet—and that ceremony had never taken place. The burnt rice was left outside, unable to enter the hamlet and growing increasingly impatient.

As soon as this negligence was established, Rangga Pinja called on all those present to commit themselves to holding the long-delayed ceremony. They agreed to try to hold it within a year, a promise the diviner repeated to the angry spirit:

This is why monkeys fell in the dark | Mono a pena ba koki mandi myete |

Cockatoos flew in disarray | Kaka walla nggole |

The trunk of the horse post | Oro kapunge pola ndara |

Traveled on the road of our words | Helu wallu lara a paneghe ma |

The great source of water | Oro mata wei kalada |

Sailed on the current of our speech | Tana tena wallu teko a patera ma |

So 1 say to you now | Mono ba hei wyali ba henene |

When the waters start to flow anew | Ba helu kendu a weiyo |

Go to wait at the edge of the planting | Tana kadanga waingo rema ela tilu |

For the rice of the sea worms | A ngagha nale |

When the rains begin to fall | Ba helu mburu aura |

Be patient by the seed platform | Kamodo waingo mangga ela londo wu |

For the rice of prohibitions | A ngagha padu |

Brought to the garden hamlet | Tana tama waingo witti ela bondo |

At the feet of Mother of the Land | Tane waindi witti a inya mangu tana |

Carried to the corn granary | Tana duki waingo limya ela |

In the hands of Father of the Rivers | Ghughu waingo limya ela bapa |

Once the rainy season began, he affirmed, the proper sacrifices would be carried out to bring the lost rice souls back into the hamlet and formally place them under the guardianship of the Lord of the Land.

Rangga Pinja rested after finally getting to the core of the marapu's distress ("the trunk of the horse post, the great source of water"). His assistant continued the interrogation, asking if there was any other unfinished business in Lolo Peka, Ra Honggoro's pasturelands. The spear indicated that something remained which could threaten the health of the livestock:

There is leftover speech | Nengyo oro paneghe |

Where you built the hen's perch | Ela pandou pa woloni keka manu |

There are traces of words | Nengyo oro patera |

Where you made the pig's trough | Ela pandou pa rawini rabba wawi |

Making the tails entangled | Ba wolongoka kiku na pa tane |

Making the snouts bite | Rawingoka ngora na pa katti |

Slipping into the hunter's net | Pa nobongo waingo a duki rembio |

Struck as they cross the forest | Pa ghena waingo pagheghu la |

The local spirits, it seemed, were upset because when preparations were made to build the stone house, a feast should have been held to announce these intentions to the marapu of the region. In the rush of assembling all the necessary materials, however, this stage had been omitted; those involved did not even sacrifice a chicken in the house to tell their own ancestors. The diviner recommended an immediate apology, with the modest sacrifice of a small pig to persuade the local spirits to wait until the stone house was finished to receive their full share.

The last offense discovered was a minor one: the Elder Spirit of the clan was annoyed because people had planted tobacco beside one of the houses in the ancestral village. This violated the division of space between the productive centers in the gardens and the centers of worship in the ancestral villages, the "land of sea worms and prohibitions" (tana nale, tana padu ). A chicken was offered to ask forgiveness ("stroke the liver, caress the belly," ami y'ate, ghoha kambu ) and assure the Elder Spirit it would not happen again.

Closing Off the Opening Between Past and Present

At last, the investigation of all the causes, great and small, of the discontent of the marapu was finished, and the diviner made his concluding statement. He began by reminding his listeners of the problems he had not found: Ra Honggoro had not been poisoned, there was no sign of witchcraft, and there was no need for a vengeance killing. The neglected feasts that they had learned of could be reasonably carried out in the next few years, as long as the ancestors agreed to accept the terms offered and not pass on resentments to future generations. The human and spirit worlds must remain separate, and these promises would provide occasions for them to reunite briefly. This funeral, though, must conclude with the reestablishment of distance.

The marapu were entreated not to take any more victims from the house, which death had emptied of all valuables. With Ra Honggoro's death, no worthy descendants remained to carry on the tradition:

No one here speaks as a great man | Njaingo na paneghe bei kabani |

Among the fruits of the yellow tree | Ela wu malandi ryara |

No one talks like a great woman | Njaingo na patera bei minye |

With the juice of the malere vine | Ela wai malere lolo |

No roosters are left to crow | Njaingo manu kuku |

No dogs are left to bark | Njaingo bangga oha |

Only snails with no throats | Di pimikya ha buku nja pa koko |

Only spiders with no livers | Di kanehengoka ha nggengge nja pa |

We are all alone and lonely | Kanehengo mono kariyo |

A special plea to the Great Spirit at the house pillar, protector of the inhabitants of the house, raised the threat of total devastation:

Mother at the edge of the corner | Inya na londo ela tundu wu kabihu |

Father at the top of the roofbeam | Bapa na ndende ela tane wu karangga |

If you break the bracelet | Ba na ndelako kalele |

Who will fetch you water | Nggarani na woni weiyo |

If they are all gone and silent? | Na kanagha ka dana? |

If you snap the rope | Ba na nggonggolo kaloro |

Who will serve you rice | Nggarani na woni ngagha |

If they are all wiped out? | Na kanguhu ngoka dana? |

There will be no one left | Njaingo dangu wemu we damu |

To bind the tall enclosures | Ba wolongo kanduru pa madeta |

There will be no one there | Njaingo dangu wemu we damu |

To repair the many corrals | Ba rawingo nggallu pa madanga |

Here on the wide stone platform | Yila kambattu mbeleko |

Here in the ancestral village | Yila parona bokolo |

This pathetic portrait of the family's decimation by death and disease, leaving it so weakened that even the simplest ritual tasks could no longer be carried out, was intended to convince the marapu that they really must leave their living descendants alone. "Now is the time to close the floor-boards, to mend the walls," the diviner repeated in the last verses he spoke. "Let the hands separate, let the feet step apart."

These words were accompanied by actions to confirm the divination and commit participants to the promised schedule of ceremonies. A pig was speared to appease the angry spirit-wife who had provided such wealth:

You who hold the buffalo's rope | Yo na ketengo a kaloro karimbyoyo |

Close as pockets of a betel pouch | A ndepeto kaleku |

You who guard the horse corral | Yo na daghango a nggallu ndara |

Tight as the folds of a loincloth | A hangato kalambo |

Who snapped open the yellow fruit | A mai mbiki nggama wuyo rara |

And chewed the green leaves with us | A mai routta nggama rou moro |

Since that meeting at the spring | Ba na mata wei pa toboko |

Since the encounter at the vines | Ba lolo ghai pa rangga |

Soften up your throat | Ropo moka a koko mu |

Stretch out your liver | Mbomo moka a ate mu |

The earlier intimacy of Ra Honggoro's rendezvous with the wild bird-woman of the forest was evoked here to suggest establishing a new sacrificial relationship with his descendants, who hoped that by honoring his earlier commitments they too could enjoy the prodigious reproduction of his herds of buffalo and horses. The capriciousness of wild spirits is notorious, however, so there was no certainty that she "would like the smell of their bodies" and accept the same intimacy with other members of the family.

Two chickens were killed to repeat promises to hold feasts: one for the rice spirits in Homba Rica, the other for the promised ceremony near the buffalo corral. The next three sacrifices were addressed directly to the spirit of Ra Honggoro. The diviner called him to come down as a kinsman and then tried to convince him to leave as a marapu :

Hear this now, cross-cousin! | Rongo baka hena, anguleba! |

This day our hands must separate | Yila lodona limya hilu hegha njandi |

Our feet must step apart | Witti ndimu deke njandi |

Do not come to the garden hamlet | Ambu ngandi ela bondo lihu, |

Do not weed the grass, dig the land | Ambu ndihi ela batu rumba, dari cana |

We are just playing with baubles | Ta mangguna waingo hario |

We amuse ourselves with trifles | Ta manghana waingo lelu |

I must tell you cross-cousin | Yo dougha taki anguleba ba henene |

We separate completely on this day | Tana ta hegha baka yila lodona |

So you can go to the spirit mother, | Tana duki wabinikya ela inya marapu, |

Arriving at the ancestral village, wide | Tana toma wabinikya ela parona |

Here you must leave behind your | Hengyo iyi mandala gha ena ha |

All these—including your daughters | Ngara iyiya, mono ena a nobo vinye |

So the separation will be complete | Tana heka a hambolo |

The chicken will mark the boundary | Hengyo a manu na hiri a lara |

Between the paths of our feet | Na ndiki ha witti |

The mixture of language in this text between casual forms taken from intimate conversation ("I must tell you now, cross-cousin . . .") and formal oratory displays the ambivalence of the ritual moment: the diviner reminds Ra Honggoro of ties of blood and friendship between them, but then asks him to go away, to accept the invisible spirits of his ancestors as substitutes for his living family. The deceased no longer needs to join his family in the fields or share their concerns, which appear as mere "trifles and baubles" of no more. consequence. The prayer began informally, gradually increasing in formality and ritual distance as the listener moved into the category of a marapu.

An egg was offered to cleanse the members of the household, "bathing their bodies and rinsing their hair with coconut" after the rituals of death. The egg was addressed as a bei wyoto, a female beast past reproductive age, whose now-sterile womb could no longer produce new life. The egg offering stood for the end of a process, the mourning and the taboos of the tou kalalu.

The last sacrifice was of a small chick to seal off the house, "closing the gaps in the floorboards, so feet could not fall through, mending the holes in the walls, so hands could not slip out." Ra Honggoro was called down

for the last time as a kinsman, then sent away with a series of lines reflecting on the inevitability of human mortality:

Once again I say to you, cross-cousin | Hena wali baka anguleba nggu |

We all die like Mbyora at the banyan | Ba mate nggama Mbyora la maliti |

There is no stopping the flow of the | Nja pa weinggelango a wete wei |

We all pass away like Pyoke at the | Ba heda nggama Pyoke la kadoki |

There is no damming the current of | Nja pa hundaronka liku loko mbaku |

We only stop to rest as we stand | Ghica piyo li hengahu ndende mema |

Here on this earth | Dani yila panu tana |

We only pause to sit for a while | Ghica piyo li lyondo eringo mema |

Here in the shade of the tree | Dani yila maghu ghaiyo |

The tide goes down at dusk | La lena ndiku myara |

The river sinks to meet the sea | La nggaba kindiki lyoko |

And what are we to do? | Mono a pemuni dana? |

The knife has already cut his death | A kiri kioto ndouka nggaka a mate |

The paddy threshed for his passing | A pare ndouka ndali nggaka a |

The metaphor of a final crossing over the river of death consigns Ra Honggoro to join Mbora Poke, the Kodi ancestor whose death also marked the origin of night and day. His widow then repeated similar verses of fatalistic resignation as she placed an offering of betel nut on his tomb. The ghost of Ra Honggoro accepted this last gift, showing that he accepted the irrevocability of death and released the living, so death would not return to their house.

Silence and Speech, Affines and Agnates

The process by which Ra Honggoro was moved from the category of kinsman into that of ancestor raises several important questions about the temporal relation of the visible and invisible worlds and the possibilities for communication between them.

The divination was not a simple "who done it" but an investigation of social tensions and collective history that encompassed much more than the details of Ra Honggoro's own life. For this reason, the "murder mystery" that began the investigation revealed not only a plethora of suspects but also a plurality of killers. Every death is overdetermined: there are

The divination to determine the reason for Ra Honggoro's death is staged as a

dialogue between an orator, who questions suspect spirits, and a diviner, who

lunges with a sacred spear to indicate positive or negative responses. 1988.

Photograph by Laura Whitney.

many more reasons for the marapu's anger than there are victims. The funeral of an important man is an occasion for reassessing the strengths of the group and reformulating hierarchical relations. During a funeral, implicit and explicit ideas of succession are sorted out in terms of seniority and precedence, and the social relations of affinity and agnation are separated.

The problem of the divination is much broader than simply finding a guilty spirit party. The important question is "Who is responsible to fulfill promises to the ancestors?" Death threatens the integrity of the group not only because it has diminished its members, but also because it signals transgressions or obligations that could claim more victims. The problem posed by death is how to turn a negative and fearful reaction into a positive value. All of the weaker connections between individual members and between ancestors and their descendants must be investigated, and these weaknesses must be bared at a conscious level for the group so that they can be resolved together.

There are two dialogues at each divination: one occurs in a parenthesis between the diviner and the human audience (supplying the diviners with clues to pursue); the other is the "official" dialogue in ritual language

between the spirits and human beings. The diviner is an outsider who is able to mediate between both groups: "his spear cuts both ways," as it is said. Confronted with the finality of death, the living are less able to dissimulate real tensions and disagreements; the spirits, then, can be compelled to provoke a true account of their anger.

The transformations attempted by ritual contrast the largely silent exchanges between affines to the intensely verbal investigation of the causes of death by the agnates. The affinal exchanges end a relationship in pantomime fashion, releasing them from all obligations, while the agnatic rites bind descendants through words and sacrifices to new promises.

The division of the funeral sacrifice into two halves, one given to the village of origin and the other to the agnatic descendants, symbolizes the division of the person into two components. Whereas the contribution of "life," given by the mother and lost at death, must be "returned," the contribution of lineage identity, coming from the father, is more enduring. It is reconstituted in the final rite, which frees the deceased of ephemeral ties and transforms him into a marapu .

As a kinsman, each man or woman is tied by contradictory loyalties to a village of birth and one of descent. The maternal line provides the "visible" attributes of physical resemblance, bodily substance, and vulnerability to disease. The ghost may still be torn by desires to respond to these earthly bonds and appetites. To become a marapu , the dead soul must be cleansed of its affinal residues and unambiguously affiliated with the agnatic descent line, with its invisible order based on ritual precedent and obligation. The "problem of responsibility" brought to the forefront at the divination can be answered only by the agnates. Death marks the dissolution of affinity at the same time that it lays the stage for the creation of new exchange relationships.

The argument I present for the dissolution of affinity through sacrifice and exchange may appear a strange one for a part of the world famous for the enduring and even eternal character of its affinal paths. In other parts of the island, where prescriptive marriage with the mother's brother's daughter supports cycles of generalized exchange among affines who remain in the same relation over several generations, things proceed differently (G. Forth 1981). Perhaps because they are aware of their neighbors' customs, the Kodi attitude is somewhat ambivalent. Affinal relations are seen as a source of vitality and blessings, the "cool and refreshing waters" that allow descent groups to reproduce and thrive. They are terminated at funerals so that they can later be revived. To use the botanic metaphor favored for the health and well-being of the lineage, the dead branches are pruned off to make room for fresh growth. If these final payments were

not made, resentments between the two villages would develop because of the unhappy state of the half-processed ghost. Since repeated alliances along an established path are highly valued, though not obligatory, generous gifts to the "counterparts to bury the dead" can influence their willingness to receive new proposals and hence to continue the relationship through time.

Alliance has great strategic value in a society such as Kodi, where there is much room for both parties either to pull out of an earlier relationship or to choose to renew it, though under somewhat different terms. The political dimension of mortuary payments is reflected in their size, timing, and distribution (and the strategic decision to include certain people in the ritual categories of affines and life-givers). Ra Honggoro's funeral became an occasion for mending one alliance tie, that to Rangga Raya, the brother of both his wives, at the same time that it ended another, the bonds to his mother's village of Bondo Maliti. The unity of the agnates was affirmed by their ability to negotiate with both other parties and, finally, to reach an accord among themselves.

Epilogue: Changing the Ties to the Past

The drama of collective guilt and debts has recently been called into question by a competing, more individualistic creed introduced by the Christian church. Ra Honggoro's widow was upset at the results of the divination and attracted to the idea of individual salvation achieved through faith and pious actions. Four months after her husband's funeral, she joined the Sumbanese Protestant church. She explained her decision thus:

The problem with these traditional rituals is that so many people now do not carry them out. My husband would not convert because he owed it to his ancestors and his family to lead them in these rites. He fulfilled his promises to the marapu , but died because others before him did not. After the funeral, I wanted to get off the ladder of these ancestral obligations. Evangelists came to my house and said that the Christian God was merciful. He asks only a small ceremony of prayers, not such large feasts. He is not as demanding as the marapu , or as strict.

Her decision was not unique: four thousand people converted in Kodi during a large Evangelical campaign that ended at Christmas 1987. Shortly after Ra Honggoro was transformed into an ancestor in the traditional way, his own kin defected, leaving behind the ancestral cult. He thus

joined the side of the authorities, those respected and worshipped if kept at a distance from the living, just as they were losing much of their authority—a tragic irony that was not lost on local observers.

Much debate about conversion and obligations to the marapu hinges not on problems of belief but on ideas of debt, responsibility, and the causes of suffering. People contract a series of obligations with invisible spirits at ritual events; for them, conversion is a way of moving into another system of obligations where the rules are easier.

Death ceremonies provide the focus for many of these debates, partly because evangelists have put pressure on many younger converts to bring their parents into the church before they die, and partly because funeral rites fix the dead person within a henceforth irrevocable status—as either ancestor or unprocessed ghost, traditionalist or Christian convert. Sacrifices and the division of buffalo dedicated to the dead person are performed in the same fashion for Christian converts as for pagans. While the church does not accept the interpretation that the liver is a message-bearer from the dead, it does not object to the silent drama of exchanges between affines and agnates, where the "gift of life" is returned to its origins. What they forbid is only the second half of the ceremony: the investigation of the causes of death through divination and the transformation of the personal soul into an ancestor. Native church leaders see the dissolution of bonds of affinity and their replacement by agnatic ones not as a distinctly "pagan" rite, but as a necessary step in the traditional exchange system. Creating new ancestors, by contrast, reproduces marapu beliefs in generations to come and is forbidden. The lines of communication with past generations must also be severed, so the church censors any direct speaking to the ancestors.

The wordlessness of affinal exchanges permits them to be classified as property transactions rather than as ritual acts. Only when the ghost is fed his last meal on the kambukelo leaf does the rite gain the label of "pagan." Christians may remove the pollution of death from their wife-takers by receiving the heads of sacrificial animals, but they may not prepare food for the ghost. The compromises involved in negotiating pagan and Christian participation inflect the temporal values of funerals by asserting that ephemeral affinal exchanges can continue, but the agnatic cult of the ancestors must come to an end. As we shall see in part three, time is one of the main battlefields on which the wars of conversion and its interpretation are fought, and it is as guardians of the past that leaders of the traditional ritual community now struggle to carry their practices into the future.