1—

Corrozet, Serlio, Androuet du Cerceau and de l'Orme

In 1550 Gilles Corrozet in his Antiquitez et Singularitez de Paris, ville capitale du Royaume de France wrote: 'There are a large number of houses [in Paris] which have declined as the times have changed and are now in the hands of others: for once there was not a Prince, Lord nor Prelat in France including the twelve Peers of the Realm who did not have a town house, because it was here as a rule that the King held Court. There are in our day some remarkable buildings in the Romanesque, Greek and Modern styles and I shall let you have the names of these for there are too many important houses to count: and every day the building of new houses goes on, which makes me believe that the City of Paris will never be completed.'[1] Around 1608 Malherbe in a letter to Peiresc wrote: 'If you come back to Paris in two years' time you will not recognize it.' Natives and foreigners wrote much in praise of the city during the sixteenth century but never go into any detail on the style and function of the buildings which in their eyes were contributing so much to the prestige and embellishment of the city. The earliest and most intriguing description of the style and function of an ideal gentleman's house came from Corrozet in 1539; a house which faced east to enjoy the sunrise, built of at least two types of good quality dressed stone including marble, with an imposing door either as an entrance gateway or on the body of the house itself, and numerous other features of note such as a forecourt paved in marble and a garden court.[2] The physiognomy of the house described by Corrozet might be imagined in a number of ways by the reader, but his house may well correspond to an early 'classic' Parisian town house on a rectangular site with the main block set between forecourt and garden and hidden from the street by an entrance screen. Corrozet does not describe the architecture of the elevations of his 'Invention Joyeuse', whether it is Gothic or Classical, Romanesque, Greek or Modern, but in one line he describes it as a 'Maison de pris, bien paincte à l'antiquaille', and later when he talks of the beauties of the garden front he lists medallions and statues both ancient and modern. The irony of Corrozet's long description is that it contains little or nothing for the architectural historian interested in plans and elevations, but it is a rare view in detail of a prestigious house through the eyes of a sixteenth-century Parisian. Apart from the quality of the materials and noting the

developed artistic tastes of the owner, Corrozet was more at pains to describe the fittings of each room from the master bedroom to the kitchen. The first published guide to the City of Paris and its monuments was Corrozet's Fleur des Antiquitez . . . de Paris of 1539 which gives the reader an agreeable historical and topographical account of the various 'quartiers' and some of their buildings, in which Corrozet shows no more interest or awareness of the changes from the Gothic to the 'classic' and classical in the town houses of his times. Contemporary printed texts are of limited value in the history of the Parisian hôtel , and so another class of book needs to be exploited, the architectural pattern books of Sebastiano Serlio (1475–1553) and of Jacques Androuet du Cerceau (c . 1510–1585) and the architectural treatises of Philibert de l'Orme (1505/1510–1570).

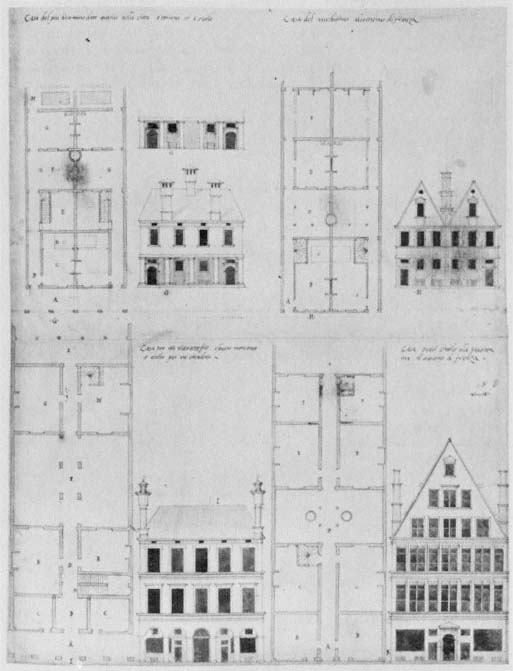

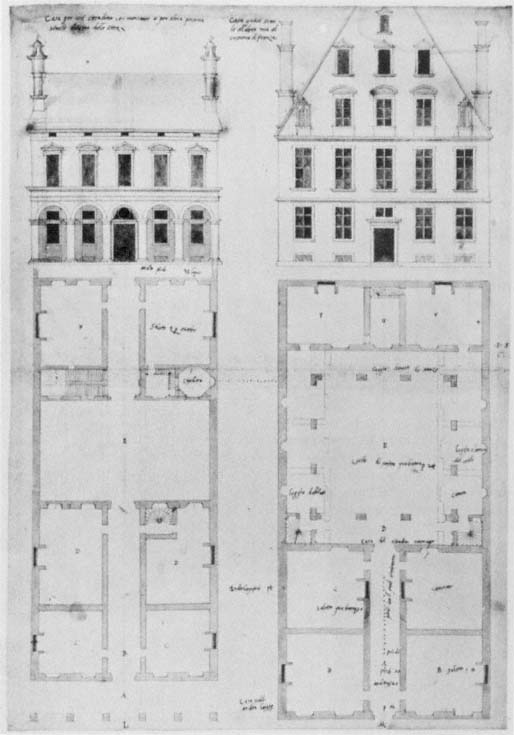

Serlio's life, career and 'literary remains' have been amply described elsewhere and there is more to come,[3] but for our purposes it is the last decade of his life spent in France preparing his pattern book On Domestic Architecture which is our first graphic and systematic evidence of the forms and styles of town houses interpreted by an Italian 'in modo di Francia' (Figs 1–5). Serlio's drawings of the plans and elevations of town houses in the Italian and French idioms are rightly said to be ideal rather than actual schemes, but his houses in the French idiom are based on unidentified and lost houses which he had studied at Paris and Fontainebleau from 1541 to 1546. The perfect regularity of the sites seen in Serlio's plans precludes any possibility that they are records of houses seen by Serlio, for regular sites were almost unknown in the built up areas within the city walls, and his drawings predate the development of the large lotissements of the later 1540s and 1550s which will be described below. The town houses drawn by Serlio range from houses for the poor artisan on to or up to houses for rich merchants, but Serlio cannot have been focusing on Paris when he wrote that the dwellings of the poorest men are located in the suburbs close to the city near the gates and therefore near to the markets and fairs. In the Paris of the early sixteenth century, with the exception of the streets nearest to the Louvre, the affluent and rich were distinguished only by the number of plots and of houses which they had acquired in comparison to their poorer neighbours. Serlio's syntheses of the artisans' and the merchants' houses summarize and rationalize some planning and building traditions known to have existed in Paris before he came to France, but the greater part of his book On Domestic Architecture deals with town and country houses for noble gentlemen, Princes and Kings. It is in these drawings of noble and princely houses that we find ideas and ideals of plan and of elevation which set revised standards for Parisian master masons and architects and created new ambitions and fashions amongst patrons. The remarkable feature of this class of designs by Serlio is how well they anticipated the new architectural opportunities of the lotissements of the mid and late 1540s.

Serlio never categorized or fully described his thoughts on the problems of building in towns, especially French towns, but scattered through his

2

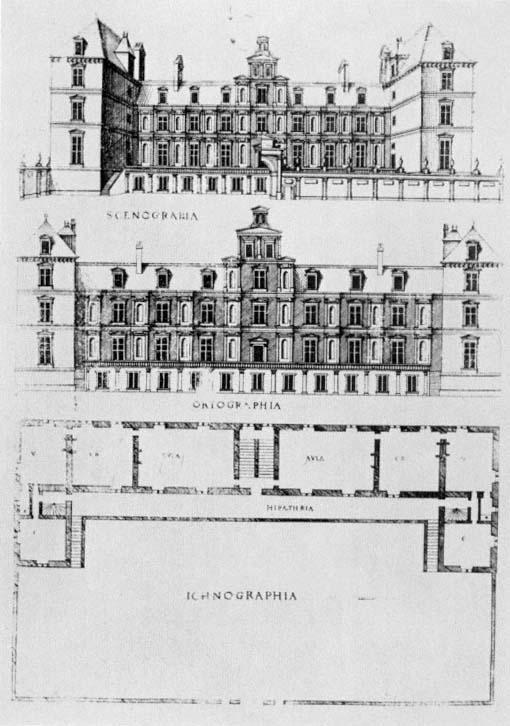

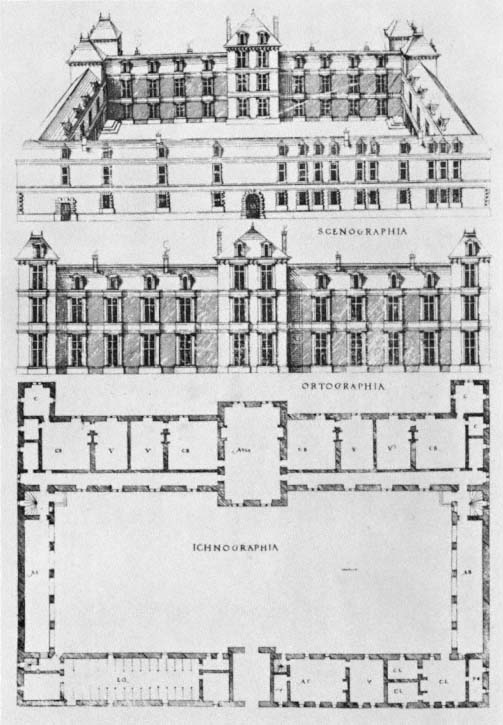

Sebastiano Serlio: Houses for bourgeois in the Italian and French manner. (Avery ms. n° XLIX)

3

Sebastiano Serlio: Houses for wealthy bourgeois in the Italian and French manner. (Avery ms. n° L)

4

Sebastiano Serlio: Houses for rich bourgeois in the Italian and French manner. (Avery ms. n° LI)

5

Sebastiano Serlio: House for a rich citizen or merchant in the French manner. (Avery ms. n° IV)

writings is a series of remarks which when collected give a fascinating insight into the relationship of patron, architect and builder, and of building tradition and styles at Fontainebleau and Paris. He insisted that the architect's first duty was to please his patron, and ' . . . la casa e fatta prima per la commoditta: piu per che pei Decoro . . .' Serlio had a keen sense of stylistic decorum which decisively influenced French writers on architecture up to the eighteenth century and which can be seen in some Parisian hôtels begun before his death. His thoughts on the decoration of the elevations of a building were both hierarchical and empirical; the most elaborate ornament (and by implication the most pretentious) on town houses should be reserved for the very great of the land, with the houses of those of lesser social rank, however wealthy, bearing fewer if any classical and armorial adornments. The empirical side of Serlio's thought is found in his acceptance and appreciation of window spacings which catered to the needs of the rooms inside, before a 'concordant disharmony'[4] , before any requirement for regularity or exact symmetry of both halves of an elevation, and which he noted as a likeable quality in French building, ' . . . where people like licentious things more than regular things.' Tall dormers were a happy French invention in Serlio's eyes, in the way in which they crowned a building, and as we know from other kinds of writing from the period, a building's imposing silhouette contributed to its romantic appeal. The decorative systems on the buildings in Serlio's drawings were no more than proposals in his mind, and were not intended as samples of model applied architecture in a dogmatic neo-classical sense. The design and proportions of decorative details and the size and use of rooms were decisions which would finally lie with the patron whom, he knew from his own experience, was likely to have opinions on such matters.

The number of drawings in the two manuscripts of Serlio's book which can be reliably associated with private houses at Fontainebleau and Paris is small. In the text which accompanies the sixth drawing in the Avery Library manuscript, Serlio summarizes the character of the houses built in and around Fontainebleau during the reign of François I as ' . . . case continuare in longezza . . .' (Fig. 5). Here the site is broad and rectangular with the main block or corps de logis built across the middle. The elevation is simple but not austere with a tall 'piano nobile' over the basement offices and stores. The pitch of the roof starts from a cornice, and the dormers are given alternating triangular and curved pediments. A double ramp central staircase leads into the vestibule from the courtyard and garden sides, and access to the attic floor is by the two spiral staircases in the small angle pavilions in the left- and right-hand corners of the courtyard. In a much quoted phrase, Serlio wrote that an outstanding quality he found in French houses was their comfort, which might be interpreted as their practicality, and we can follow in this plan the arrangements for the service functions, and the partition of the public from the private life of a Bellifontaine or Parisian house to which Serlio alludes. Corrozet spoke of the pleasure of

the sunrise, and this typical hôtel from Serlio shows a well-lit corps de logis only one room deep, an enfilade which had become standard by his day and was to remain in favour up to the late seventeenth century. Compared with Paris during the first three decades of the sixteenth century, building at Fontainebleau during the 1540s took place in more favourable conditions on large green field sites around the château and we shall see how these standards created higher expectations for building in the capital.

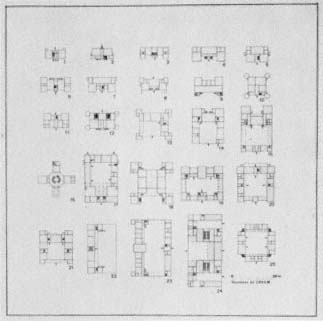

The most prolific popularizer of architectural design of Renaissance France, Jacques Androuet du Cerceau the Elder, owned or borrowed the Avery Library manuscript of Serlio's book. Du Cerceau plagiarized a great deal from Serlio, and his first Livre d'Architecture published in Paris in 1559 owes its format but few of its fifty designs to the Italian. The schemes in du Cerceau's book are all in a distinctively French manner but the book is most remarkable for the variety and fancy of its plans of the large scale buildings with square, rectangular, circular, cruciform and octagonal courtyards. The large ideal schemes may well have impressed Parisian builders and patrons with the systems of the elevations, but it is amongst the smaller projects at the beginning of du Cerceau's suite that we should look for plans which might have been conceived with Paris in mind, or more probably were based on recent Parisian buildings. The first and smallest of du Cerceau's series (Figs 8–9) for a person of 'moyen estat' is a design for a corps de logis , without any subordinate buildings or topographical context, but this is the sort of structure to be expected on a rectangular city site, on a thoroughfare.

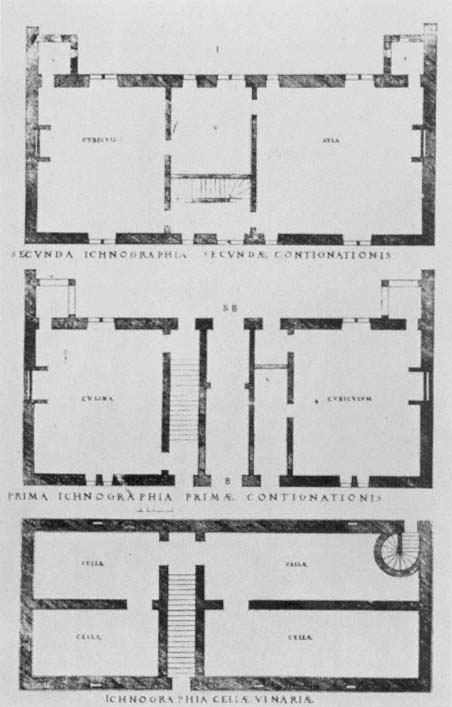

The plans of the basement, ground and first floors of this house provide an interesting social insight, with unlit cellars below ground, a ground floor where the whole of the left half is taken up with the kitchen which is evidence of a traditional bourgeois social priority, and the first flight of the main staircase leading to a first floor with from left to right a chambre (Cubiculum), garderobe (Vestiarium), or wardrobe and a salle (Aula) or hall, which would have been the living room cum dining room. The chambre with its wardrobe would have been the owner's apartment with the hall across the landing as the only reception room of the house. The use of the attic floor is not specified by du Cerceau, but it would be used conventionally for children or servants. This scheme is a perfect example of French 'comfort' as understood and interpreted by Serlio. The windows are arranged so as to give each room light in its middle, rather than any effort being made at strict uniform balance in the elevations. The street front has raised lights to keep out the gaze of the curious passerby from the kitchen and the other room on the right of the ground floor, which would have been a convenient place of business for the bourgeois. The small raised cabinets on the back of the house were to become a popular feature for courtyard and garden fronts well into the reign of Louis XIV, and inside they were rarely much larger than the five feet square in du Cerceau's design. Such tiny rooms were to be found in both town and

6

Scale plans of projects 1 to 25 of Androuet du

Cerceau's Livre d'Architecture of 1559.

Drawing by Monsieur Jean Blécon of CRHAM, Paris.

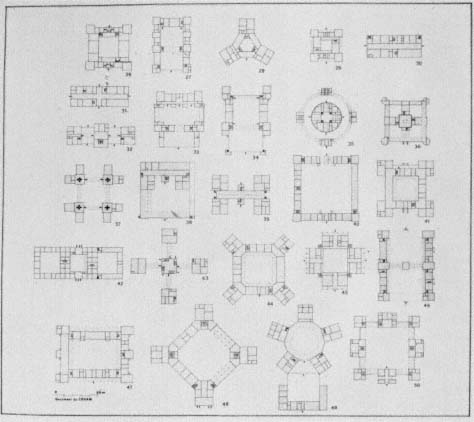

7

Scale plans of projects 26 to 50 of Androuet du Cerceau's Livre d'Architecture of 1559.

Drawing by Monsieur Jean Blécon of CRHAM, Paris.

8

Androuet du Cerceau: Plan of Project I from the Livre d'Architecture of 1559.

Cellars at the bottom, ground floor in the middle and first-floor plan at the top of the engraving.

9

Androuet du Cerceau:

Street and courtyard elevations of Project I from the Livre d'Architecture of 1559.

country houses as the inner sanctum of the owner for work, study, prayer or as a strong room for his valuables.

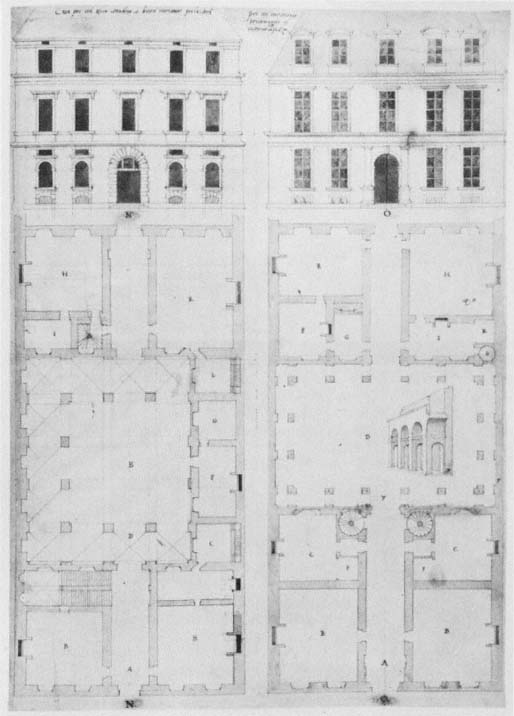

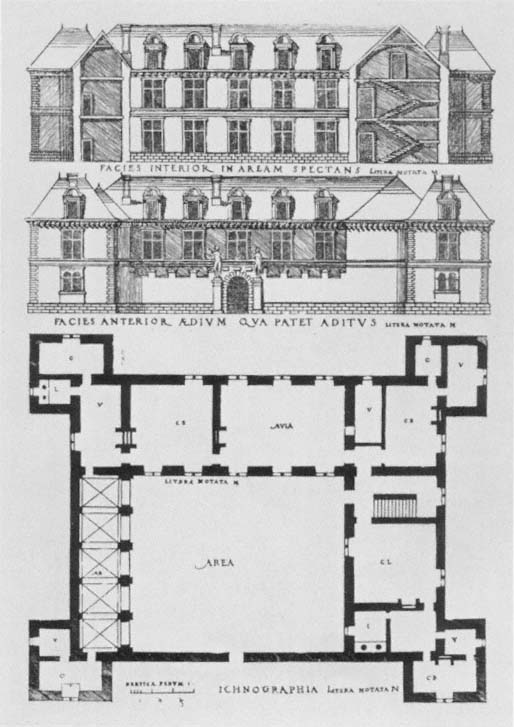

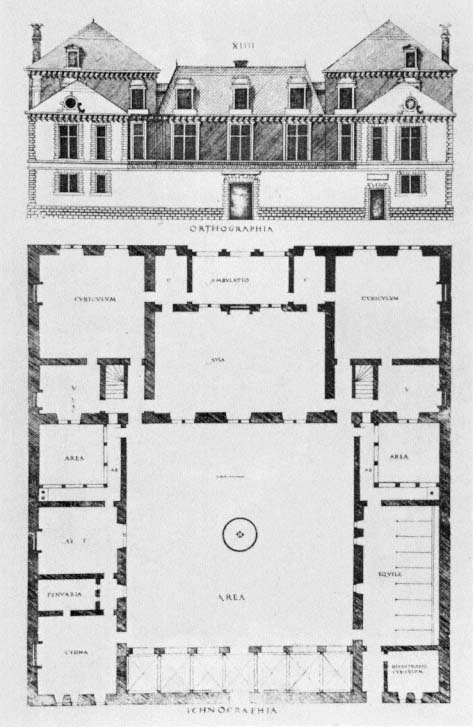

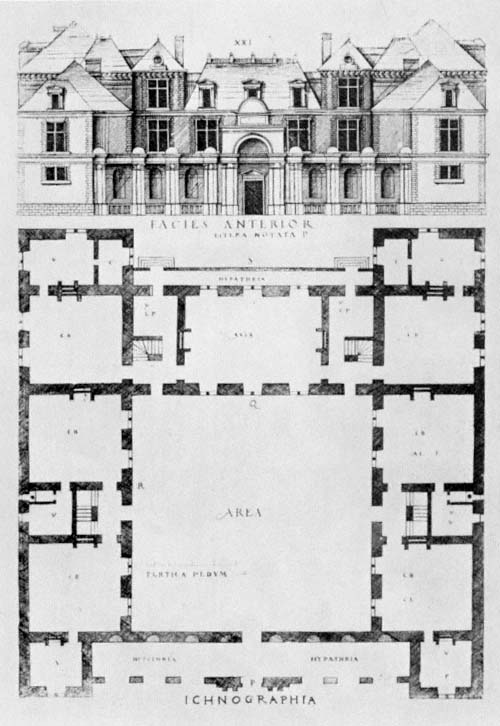

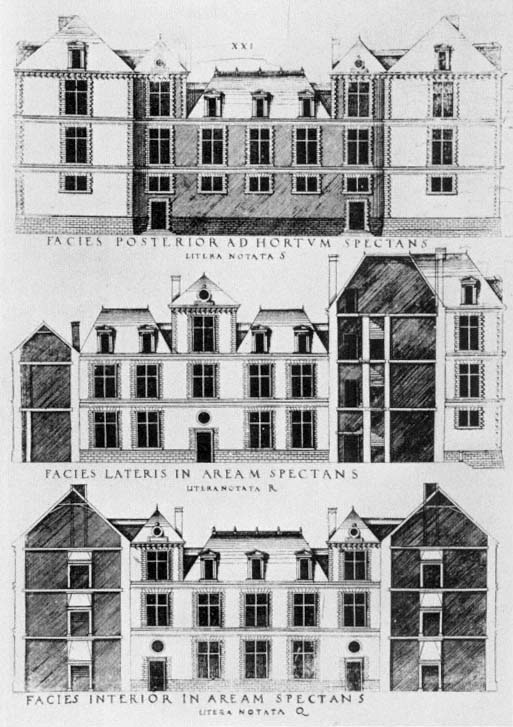

Du Cerceau's designs XIII, XIIII and XXI show the most common form of house in the Livre d'Architecture (Figs 10–13) where he explores the possibilities and varieties of square and rectangular sites. Whether he thought of them as town or country houses is irrelevant, for with minor alterations such as the removal of the angle pavilions on XIII, their size and concentration of living and service parts made them suitable propositions for either a château or an hôtel . The corps de logis of XIII is of five regular bays and two floors of equal height on the courtyard, with one bay blocked out at the back. This adjustment was made at the back because of the different widths of the lateral wings of the courtyard. The corps de logis is an enfilade one room deep entered on both floors from a ramp staircase in the right-hand corner of the court, which divides the hall and apartments from the kitchen, servants' rooms and the latrines. The truly prestigious features of this house are the battlemented entrance screen with its rusticated arch and statues, and on the left of the courtyard the arcaded gallery at the end of which was the seclusion of a small chapel or oratory. The arcade of the gallery would have been used for stores, horses and carriages, and as shelter from the rain for the attendants of a visiting dignitary. This house has a clearly organized circulation. The division between the owners and the servants is more pronounced in XIIII (Fig. 11) where two small open spaces or areas separate the corps de logis from the kitchen wing on the left and from the stable wing on the right. The windows in the corps de logis facing these small interior courts shows that they were open spaces, but the windows faced a screen to protect the ladies from a view of the kitchen staff and from the sight of the stable's lavatories. The divorce of the main block from the service buildings allows a perfectly symmetrical arrangement of rooms with access from left and right of the courtyard, rather than the one route offered in XIII. XIIII is a scheme for a substantial house, and was most suited to the city with its incorporation of the stables, which at a country house would be farther removed. We know from seventeenth-century opinion of the dislike of cooking smells amongst the nobility,[5] and from these plans the dislike was as pronounced in the sixteenth century with kitchens removed as far as possible from the main house.

The classical trappings of the elevations of houses of this scale in du Cerceau's book are limited to arcading for galleries, friezes and cornices to divide the floors, and pedimented dormers. Only on houses of a very grand aristocratic or Royal scale such as XXII (Fig. 14) do systems of columns or pilasters appear on a corps de logis . The preceding scheme (Fig. 13) which has much in common with XIII and XIIII has an austere architecture on the lateral wings and main block, to contrast with an entrance screen (Fig. 12) which is like a cryptoporticus without the requisite floor above. Its depth would have made it a public utility on a rainy day, instead of the more familiar form of entrance screen wall with its military

10

Androuet du Cerceau: Project XIII from the Livre d'Architecture of 1559.

11

Androuet du Cerceau: Project XIIII from the Livre d'Architecture of 1559.

12

Androuet du Cerceau: Project XXI from the Livre d'Architecture of 1559.

13

Androuet du Cerceau: Back elevation, lateral and middle sections of Project XXI from the Livre d'Architecture of 1559 .

crenellation or rustication. As portrayed by du Cerceau, the square courtyarded house is shown as a flexible form of plan, suitable for a strictly hierarchical society, and in which the components could be treated in various contrasting manners.

If Androuet du Cerceau's plates in the 1559 Livre d'Architecture give us a fine repertoire of house planning and style from the 1550s, shorn of the Roman and Venetian style villas, castles and palaces which complete Serlio's offering of domestic design, the Frenchman provides not one word of stylistic theory or advice. His foreword to the notices describing each building is concerned only with describing the toise (1.959 metres), the statutory unit of measurement, and costing for building contracts in Paris with regional variations. The notices on each building of the Livre d'Architecture are dry and to the point, with the total number of toises required given at the end for the reader to calculate the cost at the current prices, the first and cheapest has a total of 539 toises , 16 pieds , XXIII and XXIIII have 2610 and 2750 toises respectively, and the fiftieth and largest scheme at the end of the book has 9110 toises . Reading du Cerceau's text and browsing through the plates the modern reader can see du Cerceau keeping elaborate detail to a minimum even in the larger projects. His sense of the practical led him to publish a Second Livre d'Architecture two years later in 1561, where he illustrates elaborate and costly designs for fireplaces, doorways and dormer windows, presumably for those who have avoided trouble with their masonry contract, and might wish to add some ornate detail.

By an edict of 1557, Henri II sought to standardize Parisian methods of costing a building.[6] The Parisian convention had been to price a wall on its length, height and depth, with any decorative elements such as an architrave counted as double the unit price, and without a reduction being made for voids such as doors and windows. The Royal edict required a new system in which the voids were accounted for and deducted, and applied decorative elements such as simple pilasters, friezes and cornices were included and specified in the price for the wall. The consequence of the new regulation was that a master mason was reluctant to agree to, or to observe the finer decorative points which might be given in an architect's drawing, and a separate agreement on the basis of an agreed and initialled drawing was recommended.

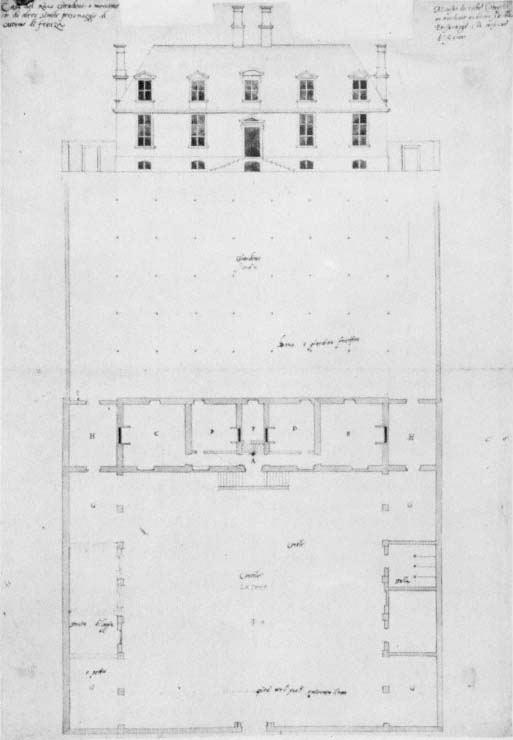

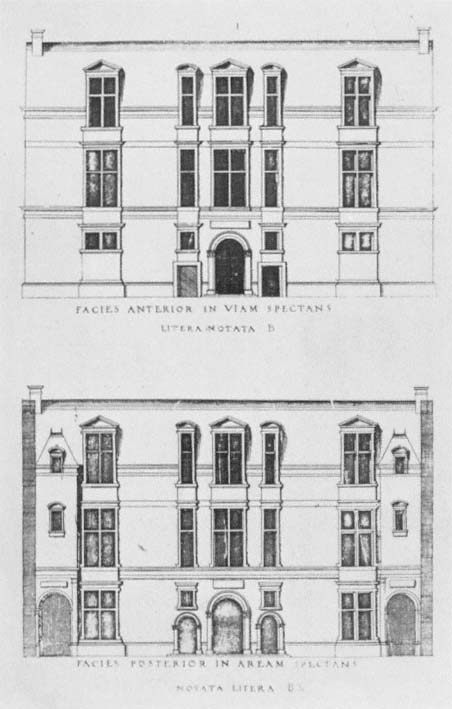

Philibert de l'Orme was the only author on architecture to speak with both theoretical and technical authority in his Premier Tome d'Architecture of 1567 and his Nouvelles Inventions pour bien bastir of 1561. In Paris he was the architect of the Tuileries palace for Catherine de Medici and of a small number of lost and unrecorded 'hôtels'.[7] In his books he had little to say which specifically concerns the topographical conditions of building in Paris, on the styles, types and configurations of town house building of his times. His thoughts on style and his expertise in building techniques and engineering are woven into an account of the châteaux designed by himself

14

Androuet du Cerceau: Project XXII from the Livre d'Architecture of 1559.

15

Androuet du Cerceau: Project XXIII from the Livre d'Architecture of 1559.

during the late 1540s and 1550s, and much of his description of building techniques is useful in an account and description of Parisian houses of the last quarter of the sixteenth century, in particular the complicated masonry of suspended cabinets and his carpentry ideas for economical pitched roofs. This egocentric and violent man only illustrated and described the house he had built for himself in the rue de la Cerisaie as a contribution to the upper middle-class town house which could be built without unnecessary expense (Figs 92–94). For this we can be grateful because here he addressed himself to the limitations and an appropriate architectural style for a house on a typical plot on one of the Royal lotissements at the Hôtel Saint-Pol near the Bastille. The plan of his house on a long-rectangular site is known, and with the three woodcuts of its elevations and with his text, de l'Orme has left both an architect's and an owner's prescription for a good town house of the 1550s, built well and without excessive cost. De l'Orme in the decade when he was building his Parisian hôtel accumulated honours from the Court and a sizeable but not excessive fortune. Despite his rise and prestige de l'Orme built a house which was about 13 metres in width, compared to the first and smallest town house in du Cerceau's Livre d'Architecture which spanned a site about 22 metres in width. The pattern books of Serlio and of Androuet du Cerceau provide abundant information on form and style which accompanies and complements the development of the Parisian town house, but du Cerceau made no attempt to record the hôtels of his native city, which is irritating in a man whose major life's work was a Royal commission to draw and engrave the great country houses of France, Les plus excellents Bastiments de France , two volumes of which were published in 1576 and 1579. De l'Orme's books have a wealth of advice on materials and building procedures which helps with an account of sites and building contracts.