Agencies of Broad Areal Scope

The remainder of this chapter will analyze the capabilities for shaping development of existing official agencies whose activities encompass substantial portions of the region. As noted at the outset, included in this category are state governments and their components, authorities and other agencies created by the states, and federal agencies. After this general appraisal, the next two chapters turn to a more detailed analysis of the regional agencies that have shaped the area's transportation network.

For this discussion, we divide regional institutions into two general groups. Most of the organizations, whether independent public authorities or line agencies of the state and federal governments, have their attention focused on particular functional problems. A few, however, such as the governors' offices and the Tri-State Regional Planning Commission, are concerned with a broad range of functional areas, and with the combined impact on urban development of various public policies. In dividing regional public agencies into two groups functional and coordinating institutions—we make a somewhat arbitrary distinction. In practice, government organizations range along a continuum from those with fairly narrow functional responsibilities (for housing, highways, parks, or sewerage) through those with increasingly wide obligations. Consequently, some organizations labeled as functional, such as the state transportation departments and the Port Authority, also provide some coordination across functional lines. And the Tri-State Regional Planning Commission, whose primary role is coordination, began as a transportation agency and has retained a heavy emphasis on transport planning and development.

Functional Agencies and the Advantages of a Focused Mission

Great diversity characterizes the region's major functional institutions. They vary widely in programmatic and areal scope, and in their ability to concentrate resources effectively on development goals. In terms of functional scope, some are highly limited—being concerned, for example, only with a particular toll road, or with parkland in a few counties. Others combine responsibilities in closely related areas, such as rail and highway transportation, or housing and commercial development. The Metropolitan Transportation Authority operates commuter railroads in New York state, as well as New York City subways and buses, the strategic river crossings built by the Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority, and airport facilities.[52] New York's Urban Development Corporation is authorized to engage in housing, commercial, industrial, recreational, and civic development. Even broader is the Port Authority's functional scope, encompassing road, rail, airport, harbor, terminal, office, industrial development, and trade responsibilities.

[52] The Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority was an independent public authority operating within New York City from its founding in 1933 (as the Triborough Bridge Authority) to its merger in 1967 into the Metropolitan Transportation Authority. The MTA now includes the following constituent units in addition to the TBTA: the Long Island Rail Road Company, the New York City Transit Authority, Stewart Airport Land Authority, Staten Island Rapid Transit Operating Authority, and two bus units, the Manhattan and Bronx Surface Transit Operating Authority, and the Metropolitan Suburban Bus Authority.

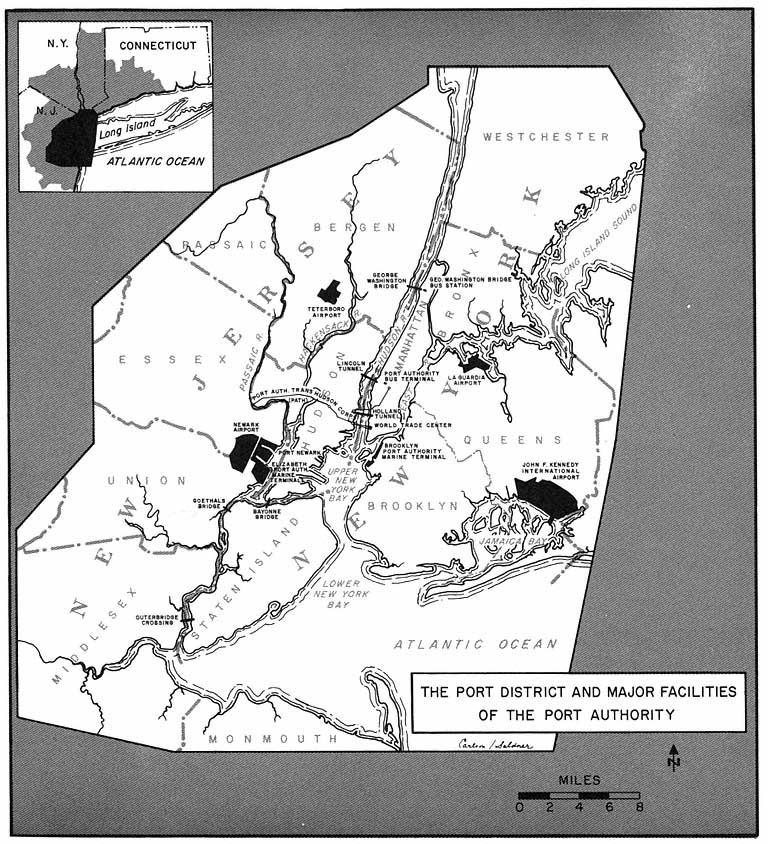

Map 7

As to areal scope, most functional agencies in the region are limited to a single state or an area within a state. The state transportation departments and housing finance agencies operate throughout each state. Among functional agencies with more limited territorial jurisdictions are the Metropolitan Transportation Authority, the state toll road authorities, the Urban Development Corporation, the Connecticut Public Transportation Authority, and the Hackensack Meadowlands Development Commission, the latter agency being restricted to 19,600 acres of strategically located marshland in Hudson and Bergen counties. The bistate Port Authority has broader areal scope, operating facilities in a port district that extends in a radius of approximately twenty-five miles from the Statue of Liberty (as shown in Map 7), and the Tri-State Regional Planning Commission extends still further, with a planning area that includes 24 of the region's 31 counties. Even broader, of course, is the territorial scope of the federal functional agencies—the Federal Highway Administration, the Urban Mass Transportation Administration, the Federal Aviation

Administration, the Corps of Engineers, and the specialized programs administered by the Department of Housing and Urban Development.

With reference to the third development variable—the ability to concentrate resources to achieve specific developmental goals—the variations are particularly complex. As outlined in Chapter One, seven factors are especially important in assessing developmental influence. Differences in the first two factors—formal independence of other governments in policy-making and in obtaining and allocating funds, and the variety and intensity of constituency demands upon an agency—are especially important in understanding the impact of functional agencies on urban development.

In the case of formal independence, one could distinguish between the semi-independent public authority and the typical line agency of a state or the federal government. The following four-way division, however, is more useful. First, some functional organizations are highly autonomous. Their governing boards are composed mainly of "independent citizens" rather than persons holding other governmental positions and serving ex officio. Also, their funds are largely derived from their own facilities, through tolls and rents, rather than being allocated from tax revenues by legislatures and political executives. In the New York region, the New Jersey Turnpike Authority and the Port Authority illustrate this category of relatively independent functional agencies.

Other agencies are moderately independent. Their funds are largely self-generated, but their governing boards are composed at least partly of persons holding other full-time government posts. The New Jersey Housing Finance Agency is an example. The agency's chairman is the commissioner of the Department of Community Affairs, and two of the other four members also head major state departments. In this situation, the organization will probably be responsive to the policy concerns represented through overlapping membership on the governing board.

A third group of organizations reverses these constraints. While their governing boards are largely independent, they rely substantially on external funding, which requires them to compete with other demands on the resources of general units of governments. The Metropolitan Transportation Authority illustrates this situation in its operation of the deficit-ridden Long Island Rail Road and New York City subway system. New York's Urban Development Corporation also has been unable to generate sufficient revenue from its projects to provide an independent financial base. As a result, the corporation had to depend heavily on state funds and federal housing subsidies. This dependence crippled the UDC when federal housing funds were severely restricted during the last years of the Nixon Administration. Declining federal support combined with inadequate project revenues and other fiscal problems to prevent the UDC from selling bonds needed to finance its program, leading to the agency's financial collapse in 1975, and a severe contraction of its programs before a firmer financial footing was achieved in 1977.[53]

[53] The UDC's financial problems are examined in Restoring Credit and Confidence: A Reform Program for New York State and Its Public Authorities, A Report to the Governor by the New York State Moreland Act Commission on the Urban Development Corporation and Other State Financing Agencies (New York: March 1976).

Finally, some functional agencies are formally dependent. As operating subdivisions of the state or national government, they are under direct authority of an elected official and his appointed agency head, and also must compete for funds in the general budgetary and appropriations processes. An example is the New Jersey Department of Transportation. Somewhat more independent financially, at least with respect to road building, are the transportation departments in the other two states, since Connecticut and New York dedicate gasoline taxes to highway construction. The Federal Highway Administration and its predecessor, the Bureau of Public Roads, also have enjoyed greater financial independence than most federal functional agencies, because gasoline and other taxes dedicated to road building supply a significant share of its funds.

Functional agencies rarely confront constituency demands that are as varied and intense as those which form the standard fare for mayors, governors, and legislators. Even so, the behavior and roles in urban development of these organizations are affected by differing patterns of public pressure. For some agencies, external pressure is focused on a narrow set of issues, and is of low intensity. For example, some turnpike authorities deal mostly with demands for good traffic conditions (and at times for expansion in the number of lanes) over routes determined long ago, as well as intermittent conflict over proposed toll increases. Other agencies, with more varied functions, must be more sensitive to competing interests in setting policy and investing resources. For example, the Port Authority has constituencies that seek additional investment in harbor terminals or rail service, from funds that might otherwise be used to expand the World Trade Center or add to airport facilities. Still other functional agencies, such as the highway departments, must balance directly conflicting demands—for new highways, and for avoiding local disruption where those highways would be constructed—while at the same time competing for funds in the legislative arena with other public agencies.

When constituency demands are intense and involve conflicting goals, the development activities of even the most powerful functional agencies can be checked. This is especially true when pressures are brought to bear on general governments having authority over the functional organization. An example is the Port Authority's inability to build a fourth airport, in the face of a broad coalition of grass-roots interests supported by key state and federal officials. Also, as seen in Chapter Four, the ability of the region's highway agencies to implement their plans has been sharply reduced as environmental restraints have enchanced the influence of those who oppose particular highway facilities and alignments.

Even when a functional agency has a high degree of formal independence, it will sometimes find that the few remaining strings of broader public control can be tightened abruptly. In the case of the fourth jetport, for example, the need for legislative action to expand the port district provided a crucial route for constituency action to prevent the Port Authority from constructing its airport in the Great Swamp. Similarly, the need for formal approval by the state legislature before the New Jersey Turnpike could be extended into Monmouth and Ocean Counties allowed opponents to contest the proposed road in the state's general political arenas, rather than within the unpromising decision-making confines of the New Jersey Turnpike Authority.

Constituency pressures may also become so intense that the functional agency suffers a significant loss of formal independence. A case in point is the authority of the Urban Development Corporation to override local zoning and building codes in order to develop its projects. When the UDC tried to use these powers to build low- and moderate-income housing in the affluent suburbs of northern Westchester County, intense pressures were brought to bear on state legislators to strip the public corporation of its override power. The UDC was particularly vulnerable at the time (1973) because of its deepening financial problems, and legislative authorization for $500 million in bonds was desperately needed. To get the money UDC had to relinquish its power over local land-use controls in suburbs, and in the process its ability to have any significant impact on suburban housing patterns.[54]

Despite these great variations in scope, formal independence, and constituency demands, the region's functional agencies share several characteristics that greatly enhance their ability to significantly affect urban development. Most important is the narrow functional perspective these agencies bring to bear on every problem. This perspective, shaped by statute and reinforced by the background and experience of the agency's officials, tends to ensure that the organization will be insensitive to many of the values that are affected by its actions. There is nothing like a wide perspective and concern with the multiplicity of human problems in a metropolis to render a participant immobile. In contrast, there are few characteristics more valuable in "getting the job done" than a vigorous, single-minded concentration on, for example, placing a highway where land costs are lowest.[55]

This limited focus is strengthened by the pattern of organizational relationships which has evolved in important areas that affect urban development. Commonly, the most active constituencies of functional agencies are the trucking and automobile associations, real estate entrepreneurs, and other private interests that expect to benefit from agency activities. Moreover, alliances have been created among federal, state, and local agencies in various functional areas, and through these alliances, substantial amounts of funds—especially from the federal government—have been made available to finance particular functional programs. Access to these funds reduces a functional agency's dependence on funds controlled by state and local elected officials, and thus decreases the responsiveness of these organizations to broader policy concerns felt in the offices of the governors and mayors. Insulation from such concerns also occurs, of course, when agency funds are largely derived from its own revenue-producing projects.

As a result of these circumstances, policy decisions in important program areas often do not evolve from public discussion of alternatives and their implications. Instead, they frequently are determined by informal, low-

[54] The state legislature permitted the UDC to retain its power to override local codes in older cities. For a general discussion of the UDC, local zoning, and the state legislature, see Danielson, The Politics of Exclusion, pp. 306–322.

[55] These observations, are not, of course, intended as an endorsement of a narrow approach to urban development. Some of the "accomplishments" that result from the tunnel vision of functional agencies are projects that should never have been undertaken at all, or that would have been more useful (at least by some criteria) if they had been modified with regard to a broader perspective on the urban development process.

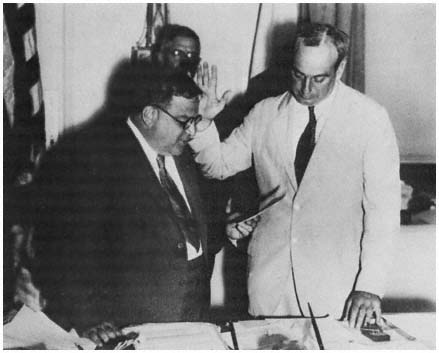

Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia swears in Robert Moses

as a member of the Triborough Bridge Authority in 1935.

Credit: Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority

visibility negotiations among government agencies in a particular functional area, joined or supported by prospective beneficiaries in the private sector. These constituency relationships stand in sharp contrast to the variety of conflicting public demands that confront, for example, the mayors of the region's older cities.

Another key advantage of many functional agencies is their ability to attract skillful leadership. The organizational and financial autonomy of these enterprises provides opportunities for their leaders to exercise significant influence. Consequently, individuals who like to wield power—especially when visible and dramatic achievements can result—and who are skilled in the use of power are attracted to these organizations. Robert Moses was the archetype of the political leader whose influence derived from personal chemistry joined with the organizational and financial independence available to leaders of the public authority. With great energy, vision, and ruthlessness, Moses welded the Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority, the Long Island Park Commission, and other functional agencies into a formidable power base, and in the process exercised substantial influence on the region's development.[56] Other major public corporations in the region have also at-

[56] Moses's career is examined in exhaustive detail in Robert A. Caro, The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1974). For a different version of his accomplishments, see Robert Moses, Public Works: A Dangerous Trade (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1970).

tracted highly skilled leaders, such as Austin Tobin at the Port Authority, William Ronan of the Metropolitan Transportation Authority, and Edward Logue of the Urban Development Corporation.

In addition to strong leadership, these agencies can draw on large and able staffs, and on a host of specialized consultants. Public authorities are in a better position than line functional agencies (e.g., state highway departments) with respect to staff and consultant resources, since the authorities are generally less constrained by civil service regulations and formalized bidding procedures. Formally autonomous agencies also are less vulnerable to outside political pressures to hire particular individuals or consulting firms. Of all the region's functional agencies, the most impressive staff resources have been developed by the Port Authority, which is run by a corps of well-paid officials, many of whom have spent much of their careers with the authority and are strongly committed to the agency's relatively narrow organizational and developmental goals. Over the years, this group usually has provided the Port Authority with skillful financial management, effective long-range and project planning, efficient project development and management, and imaginative public relations.

Finally, functional agencies frequently demonstrate strong planning capabilities, compared with other organizations in the metropolis. As defined in Chapter One, planning is the "application of foresight to achieve certain preestablished goals in the growth and development of urban areas." For general urban planning agencies, and for many program agencies, this activity is fraught with difficulties. Long-range goals are frequently unclear, and the extent to which particular programs aid in achieving broader goals (when such goals can be specified) is very difficult to measure. These problems are more tractable in functional agencies concerned with highways, bridges, urban development projects, and other programs where direct output can be assessed in quantitative terms, such as miles of highways built, or traffic flow improved, or land cleared. Consequently, these organizations often develop skilled and aggressive planning staffs, whose members are of great value to the agency's leaders in providing guidance regarding specific strategies that will maximize the organization's ability to achieve its long-run goals.[57]

[57] See, for example, Harold Kaplan, Urban Renewal Politics: Slum Clearance in Newark (New York: Columbia University Press, 1963). This discussion touches on a broader set of issues regarding an organization's "goals." Analytically, three distinct kinds of goals are pursued by officials of functional agencies (and all other organizations as well). First, there are external goals, those purposes the organization was created to accomplish. In the case of urban development, these include goals like improved transportation, better housing, or a more prosperous economy. Such goals provide the public rationale for government action in various policy areas, and they are usually stated in the statutes that establish the agency.

Second, there is the goal of organizational maintenance. At the most basic level, this refers to keeping the organization in existence. More broadly, it involves protecting the ability of the organization's officials to exercise discretion in making decisions and allocating resources, so that the organization can grow in size and influence.

The third goal is personal maintenance. Individuals often join an organization because they support its external goals. And they may, especially after long service, come to identify with the agency's survival and growth. But most organization members will sacrifice or disregard external goals and organizational-maintenance goals if pursuit of those goals is likely to conflict with personal self-interest. Such conflicts occur if agency policies intended to achieve those broader goalsare viewed as likely to affect adversely a member's personal well-being (e.g., leading to his being fired, demoted, fined, or merely inconvenienced in his regular activities within the organization).

Generally, an organization's policies cannot be understood by reference to only one of these kinds of goals. Decisions that enhance the prestige of agency leaders, for example, often increase the prospects for the agency's continuance and expansion as well. And not infrequently, such decisions do advance at least some of the organization's external goals. But a pattern of action that seems to undermine some of the agency's external goals, while strengthening its survival aims and perhaps some personal-interest values, is common enough to justify making this distinction among different aspects of an organization's goals.

These characteristics of functional agencies do not operate in isolation from one another. As the discussion above suggests, they reinforce and strengthen each other. The narrow path set by statute justifies functionally limited planning and action, and discourages political opponents—who might challenge narrowly focused policy were it not already legitimized by statute and rule. Insulated revenue sources, combined with this legitimacy, encourage leaders to act vigorously and decisively, and attract those who seek public influence unencumbered by the need for wide consultation and compromise.

We are not arguing, however, that these organizations operate without constraints. Compared with general governmental units such as the governor's office, their scope is restricted functionally, although such program areas as highways and housing tend to have a wide collateral influence in shaping development. Some are highly restricted in areal scope as well, being limited to particular sectors of the region. This limitation is mitigated, however, through vertical and horizontal alliances in such areas as road building, which tend to ensure similar policies and results across much of the metropolis. The operation of such an alliance in the case of highway construction is examined in the next chapter. In addition, these agencies often find their lack of control over land to be an important obstacle to action. Examples of the delays and failures that result from this limitation are recorded in Chapter Four, where the highway agencies' struggles to complete major routes and the unsuccessful effort of the Port Authority to locate a site for a fourth jetport are described.

Moreover, like all institutions, functional agencies are faced with the continual necessity to adapt to change. The inability of Robert Moses to adjust to changing development values and political realities, as well as the decline of his personal skills with advancing age, eventually cost the Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority its independence. The failure of road building agencies in the region and the nation to secure additional sources of revenue for new projects greatly constrained their developmental capabilities in recent years. And the sharpened public interest in official misconduct in the post-Watergate era—as well as heightened interest on the part of journalists and their editors in corruption and improper official behavior—made the revelations of expense-account padding on the part of some Port Authority officials far more damaging to the agency's image and credibility in 1977 than it would have been a decade earlier.[58]

[58] A 1960 investigation of the Port Authority by Representative Emanuel Celler of Brooklyn, a longtime critic of the agency, produced some evidence of improper activity on the part of the Port Authority, but these disclosures had little impact at the time on the PNYA's reputation for probity and businesslike efficiency; see Doig, Metropolitan Transportation and the New York Region, pp. 263–264, 299–300; and U.S. House of Representatives, Committee on the Judiciary, Port of New York Authority, Hearings before Subcommittee No. 5, 86th Congress, second session (Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1960). The 1977 investigations are discussed in Chapter Seven.

In summary, the activities of functional agencies tend to be characterized by narrowly focused rationality rather than responsiveness to a broad range of constituency interests. While the general political leadership of the older city, a state, or the nation must be sensitive to a wide variety of demands, the program agency enjoys a substantial degree of isolation from these pressures. Statutory and financial insulation are joined with skilled leadership and specific yardsticks of success to permit the functional organization to calculate its future goals and current strategies more clearly, and with greater likelihood of success, than is true for hard-pressed mayors, governors, or members of Congress. The cumulative result is a set of organizations that operate from narrow perspectives and yet can have a broad impact on urban development in the region.[59]

The Coordinating Agencies: Modest Resources and Multiple Constraints

We now turn to those institutions which have the broadest range of public concerns with urban development: the three states, the federal government, and their coordinating agency in the New York area—the Tri-State Regional Planning Commission. Our concern, however, is not with the states and the federal government as a whole. As pointed out above, most state and federal agencies whose actions have an impact on urban development are limited to narrow functional concerns. Our interest in this section is those regional actors who are responsible for the interrelationship of programs across a wide range of development areas. At the state level, these include the governor's office, the legislature, and the agencies responsible for regional planning and development; at the federal level, the President and his staff, Congress, and the Department of Housing and Urban Development; and within the region, the Tri-State Regional Planning Commission. For some of these actors, such as the gubernatorial office in a state, the coordinating role is an inevitable part of a general responsibility for policy-making and resource allocation. For other coordinating agencies, such as the New Jersey Department of Community Affairs, functional scope is more restricted but still embraces a wide range of state and local policies that affect urban development.

Although the explicit coordinating responsibilities of these organizations imply that they have a major role in shaping urban development, in fact their influence as coordinators is greatly restricted, for a number of reasons. First, the most powerful of these organizations—the executive and legislative units at the state and federal levels—devote much of their time and resources to issues that do not have a primary influence on the pattern of urban development. The White House and Congress are preoccupied with foreign affairs, defense, national economic policy, and general social programs. At the state level, urban development competes for executive and legislative attention with a variety of other matters, such as education, health, welfare, and criminal justice. Moreover, many federal or state issues with important implications for urban development—such as energy policy, interest rates, environ-

[59] The perspectives and behavior of public authorities are analyzed in Annmarie Hauck Walsh, The Public's Business: The Politics and Practices of Government Corporations (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1978). On the nature of authority leadership, see especially Chapters 7–8.

mental constraints, or school-aid distribution formulas— rarely are considered in Washington or the state capitals primarily in terms of their impact on the distribution of residences, jobs, and transportation facilities.

A second limitation is the existence of significant state and federal constituencies that lie beyond the New York region. In 1975, 33 percent of New York State's population lived outside the region, as did 21 percent of New Jersey's inhabitants and 45 percent of the residents of Connecticut. Approximately the same proportion of each state's legislators represent districts wholly or largely outside the metropolis. Moreover, because of the region's size and complexity, most of the state legislators whose districts were within the tri-state area did not perceive the region as a whole as a relevant frame of reference either for themselves or their constituents. City-suburban conflict divides the New York area's representatives in all three state legislatures, and is particularly sharp in New York State—where suburban legislators are far more likely to make common cause with upstaters against New York City than to join forces with the city's representatives in Albany. For their part, governors and their staffs tend to think in statewide rather than regional terms on most issues.

Similar considerations are at work in Washington. Less than 10 percent of the nation's population lives in the region, and the proportion steadily declines as people move south and west. Only thirty-eight members of Congress had districts primarily in the region in the 1970s. And the diversity of their constituencies combines with individual differences within the area's congressional delegation to foreclose cohesive action on most federal issues affecting the New York region. At the White House and in federal coordinating agencies, the primary concern is with general national policies rather than with the problems of individual regions. As a result, urban development programs emanating from Washington often fail to take account of the special problems raised by the nation's largest and most complex metropolitan area.

Another restraint on these coordinating agencies is the absence of a political culture of constituency demands that are favorable to broad-gauged planning and coordination. Most of the demands from the region that are pressed upon governors or Congress come from specific functional or territorial interests. Underlying this structure of demand is a political heritage in the United States that favors public policy outcomes resulting from bargaining among organized interests, and which gives rise to suspicion when "comprehensive planning" by central units of government is advocated.[60]

In confronting this antagonism to planning, central organizations bring varying strengths and limitations. The potential influence of elective institutions—the President and Congress, the governors and state legislatures—is substantial when measured in terms of their high degree of formal independence and financial capacity. The states also possess potential control over land use in every city and town. Yet the ability of these political institutions to shape urban development is heavily constrained, both by the diversity of

[60] See, for example, Alan Altshuler, The City Planning Process (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1965), and Edward Banfield, Political Influence (New York: Free Press of Glencoe, 1961).

constituencies and an "antiplanning" tradition, and by several characteristics that flow out of and reinforce these conditions. Actual control over the use of land has been ceded by the states to municipalities. A variety of public authorities have been given a wide measure of formal autonomy and fiscal independence from central control. Moreover, elected officials rarely have urban planning units attached to their own offices.

In sum, the institutions with the greatest potential influence would face considerable obstacles should they attempt to establish goals for urban areas and shape public policy to achieve these objectives. Moreover, elected officials often share in their personal attitudes the widespread belief in the advantages of local and functional autonomy. And, regardless of personal preferences, they commonly seek to avoid involvement in such conflictladen issues as coordinated planning, where proponents are likely to be denounced for "undermining home rule" or for "playing politics" with independent agencies.

All of these constraints are illustrated by the failure of various efforts to have state governments exercise greater control over land use in the region's suburbs. Legally, the three state governments have complete power over their subdivisions. They can restrict local zoning authority so as to eliminate large-lot zoning or prevent certain types of commercial activity. Or the states could take back the powers to regulate land use which have been delegated to local government, either performing the function themselves or assigning it to the counties or regional agencies. The legal potential of the states is largely neutralized, however, by political realities. All local governments—in older cities, rural areas, and suburbs—perceive a common interest in maximizing local control over local turf. These interests are well-represented in the legislatures of Connecticut, New Jersey, and New York. In addition, all three states have strong home-rule traditions that provide a rationale for those who defend the municipal status quo in zoning.

As a consequence, measures that threaten local control over land in the name of more rational and coordinated development rarely attract much support in the state capitals. In 1967, suburban opposition foreclosed action on a Connecticut bill setting one acre as the maximum lot size in the state. The fight against the bill was led by officials from Darien, New Canaan, and other affluent suburbs in Fairfield County where lots of two to four acres were common. Proponents of the bill argued that zoning laws designed "to keep the peasants out are putting out the flame under America's melting pot." Suburban opponents answered that "the issue is simply whether or not communities can continue to determine their own destinies"; and countered with a proposal that the state constitution be amended to guarantee municipal control over land-use regulation.[61]

Two years later, a furor developed in New Jersey when the administration of Governor Richard J. Hughes sought to take away some of the authority delegated to local governments in the Municipal Zoning Enabling Act of 1928.

[61] Representative Norris L. O'Neill, Democrat of Hartford, and Representative Lowell P. Weicker, Jr., Republican of Greenwich, quoted in William Borders, "Suburban Zoning is Again Attacked," New York Times, March 26, 1967. Weicker at the time was also first selectman (i.e., mayor) of Greenwich.

The proposed law required local zoning ordinances to consider the housing needs of all economic groups, as well as regional transportation and open space requirements, and state, county, and regional plans. It prohibited the use of zoning to exclude anyone for racial, religious, or ethnic reasons, and shifted the burden of proof in such matters from the challenger to the municipality. Also proposed was a state role in land-use regulation in flood plains and in areas adjacent to airports, highways, and parks. Less than two weeks after the proposals were made public, adverse reaction had become so vehement that Commissioner Paul N. Ylvisaker, whose Department of Community Affairs had developed the new legislation, found it necessary to begin a discussion of the issue by emphasizing what was not in the bill: "There is no state zoning. There is no reduction in local zoning power," Ylvisaker insisted. "There is nothing here that can force a municipality to provide low-income housing. . . . No state planning czar or super-agency is created to oversee local zoning."[62] But Ylvisaker failed to put local fears to rest. Municipal opposition was overwhelming, and legislators responded to their constituencies by killing the bill in committee.

In New York, state legislators gave short shrift in 1971 to proposals to prohibit discriminatory zoning, establish state standards for acreage and floor space in new housing, and require that towns which zoned for industry also zone some areas for housing within the financial means of industrial workers. At the same time, another effort was underway in New Jersey to modify suburban land-use controls in order to ease what Governor William T. Cahill called the state's "crisis in housing."[63] Although Cahill's actual proposals were modest, his tough talk about "statewide zoning" and the need for "harsher measures if nothing else works" alarmed local officials and legislators.[64] Reaction was so vehement that Cahill was abandoned by most fellow Republicans in the legislature, and his program perished in committee. Suburban dissatisfaction with what opponents of the zoning proposals called a "Cahill power grab" also played a part in the governor's defeat in his bid for renomination in the 1973 Republican primary, at the hands of a vigorous defender of local autonomy.[65]

Cahill's successor, Democrat Brendan Byrne, was equally unsuccessful

[62] Quoted in Arthur G. Kent, "The Zoning Issue: A Study of Politics and Public Policy in New Jersey" (Senior Thesis, Princeton University, 1972), p. 44. Kent provides a useful account of the local and legislative reaction to Ylvisaker's proposal.

[63] A Blueprint for Housing in New Jersey, A Special Message to the Legislature by William T. Cahill, Governor of New Jersey (December 7, 1970). Cahill, a Republican, succeeded Governor Richard J. Hughes in January, 1970, following his successful 1969 campaign against former Governor Robert B. Meyner.

[64] Quoted in Earl Josephson, "Cahill Wants Zoning Solutions," Trenton Times, August 13, 1970; and Ronald Sullivan, "U.A.W. Maintains a Jersey Suburb Keeps Out Poor," New York Times, January 28, 1971. Cahill's housing and land-use program called for state-determined quotas for low-income housing with voluntary compliance by municipalities, creation of a Community Development Corporation whose proposed projects would be subject to local veto, a uniform statewide building code, and simplification of the laws governing local zoning. The proposal for state-determined housing quotas was the most controversial element of the package.

[65] John Chappell, president, United Citizens for Home Rule, quoted in Dan Weissman, "Home Rule: Local Forces Line Up Against Statewide Planning Bills," Newark Sunday Star-Ledger, April 24, 1973. Cahill was defeated in the primary by Representative Charles W. Sandman, Jr., who then was beaten in the general election by Brendan T. Byrne.

in persuading the legislature to alter local control over zoning. On the most controversial aspect of the zoning issue—the provision of low-income housing in the suburbs—Byrne sought to bypass the legislature by directing the Department of Community Affairs to prepare a "fair share" plan which would provide low-income housing guidelines for each community in the state. Localities that failed to comply with the plan could face the loss of state aid for education, sewers, and other programs. Suburban legislators attacked Byrne, challenging in state court his authority to alter local control over land by means of an executive order, and proposing an amendment to the state constitution that would safeguard local zoning.[66] In the face of suburban hostility, Byrne soft-pedaled his support for dispersing low-income housing and emphasized the need for rehabilitation in the older cities rather than new subsidized construction in the suburbs.[67]

Appointed officials concerned with urban development and regional planning tend to be more oriented than most elected officials toward the advantages of broader coordination. Career officials of state planning agencies usually have been involved in developing the housing and land-use proposals which legislators have resisted. Despite their location in state agencies with access to the governor, however, state planners and other appointive officials with broad perspectives typically play modest roles. State plans do not govern the actions of local governments or other state agencies. As a result, state planners offer advice and serve as public advocates for a broad-gauge approach to urban development, while—as described in Chapter Three—local governments regulate actual land use using very different criteria. And functional state agencies undertake the highway, sewer, water, and other public projects which strongly influence the pattern of development in the region.

Federal efforts to coordinate urban development are thwarted by similar forces and pressures. Most federal resources reach the metropolitan area through functional programs—for roads, sewers, water supply, mass transportation, mortgage insurance, and a variety of other housing, transport, and community development programs. Functional agencies and their clienteles have strongly resisted efforts that threaten to dilute the specific goals of narrowly focused programs. For example, the attempt by the Department of Housing and Urban Development in 1969 to use water and sewer grants as a lever to force suburbs to accept lower-income housing was successfully resisted by beneficiaries of the grant program and their supporters in Congress. Bergen County's Republican congressman, William B. Widnall, led the attack against HUD's efforts, arguing that local needs for water and sewers rather than regional housing considerations "should be primary" in distributing federal funds under the program.[68]

[66] See Ronald Sullivan, "Housing Goals: List Stirs Debate," New York Times, September 19, 1976; and Martin Waldron, "What Limit Executive Power?" New York Times, July 17, 1977.

[67] See State of New Jersey, Division of State and Regional Planning, A Statewide Housing Allocation Plan for New Jersey, Preliminary Draft for Public Discussion (Trenton: November 1976); Ramona Smith, "Governor Waffles on Poverty Housing," Trenton Times, December 9, 1976; and Joseph F. Sullivan, "A Softening of Some Issues," New York Times, December 10, 1976.

[68] Quoted in Barbara Gill, "Readington May Seek U.S. Aid Again," Trenton Sunday Times Advertiser, August 8, 1971. Widnall was one of the original sponsors of the water and sewer legislation, as well as the ranking minority member of the Banking and Currency Committee which handled the water and sewer program and other HUD activities.

Efforts by HUD to coordinate and guide urban development are also weakened by its own functional activities. Water and sewer officials in HUD were much more interested in advancing their program than in spreading low-income housing—especially since the housing objectives aroused suburban and congressional hostility, and thus threatened the water and sewer program. Similarly, the broad goals of the Housing and Community Development Act of 1974, which sought to increase housing opportunities in the suburbs, have been subordinated to HUD's desire to maximize suburban participation in the community development grant program. In the program's initial years, HUD made little effort to ensure that participating suburbs were preparing housing plans that complied with the statutory federal requirements.

Because of these constraints, federal officials concerned with urban development have attempted to encourage coordination through institutional development at the metropolitan level. A principal federal goal has been the creation of areawide institutions capable of planning comprehensively and of coordinating the development activities of local, regional, state, and national agencies. Federal grants have been available for comprehensive planning since the late 1950s. Beginning with the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1962, an expanding list of federal functional grants in metropolitan areas has been conditioned on the existence of a comprehensive planning process carried on by state and local governments. Since 1966, Congress has required that all applications for federal grants in a number of key urban programs be reviewed by a regional agency to ensure that the project was "consistent with comprehensive planning developed or in the process of development for the metropolitan area."[69]

In response to these federal requirements, regional agencies sprang up in every metropolitan area in the nation, and they soon were grinding out all sorts of comprehensive plans. Few of these agencies, however, have evolved into influential participants in the development process, Most were organized in order to ensure the continued flow of federal aid, not because of strong commitment to regionalism on the part of local or state officials. A number have been dominated by highway interests because the earliest federal requirements for comprehensive planning dealt with roads and mass transit. Consequently, most of the plans produced by these agencies reflect the particularized interests of existing governments in the area and of major functional groupings. Controversial issues typically are avoided, particularly those arising from social, economic, tax, and service differences in the metropolis. With few exceptions, regional agencies have not obtained control over land use, important operating responsibilities, an independent financial base, or other means of ensuring the implemention of their plans.[70]

Reinforcing the weakness of the regional coordinating agencies has been the ambiguity of the federal government's commitment to its metropolitan offspring. Little real power has been provided to these agencies by Washing-

[69] Section 204, Demonstration Cities and Metropolitan Development Act of 1966, 80 U.S. Statutes at Large (1966), p. 1262. Under this law, programs subject to review were airports, highways, other transportation facilities, sewers, water supply, open space, conservation, hospitals, law enforcement, and libraries. Over the next decade, scores of other federal grants were added to the list, which totalled over 140 grant programs in the mid-1970s.

[70] See, for example, Melvin B. Mogulof, Governing Metropolitan Areas: A Critical Review of Council of Governments and the Federal Role (Washington: Urban Institute, 1971).

ton, largely because of resistance by functional agencies and grass-roots interests to any authoritative role for general-purpose regional bodies. Thus regional agencies evaluate federal grant requests in terms of their compatibility with metropolitan plans, but federal agencies that administer the various aid programs are free to disregard their recommendations. And when general revenue sharing and block grants for community development were initiated in the early 1970s, neither program made any provision for distributing funds to metropolitan agencies. Instead, all federal assistance was allocated to local governments, thus reinforcing their development capabilities and reducing further the relatively weak role of regional planning units in the development process.

In the New York area, federal ambiguity has combined with the region's size and complexity to produce a coordinating agency with almost no independent influence on urban development. The Tri-State Regional Planning Commission was created by the three states to ensure federal funding of highway and transit projects in the metropolis. Organized as the Tri-State Transportation Committee in 1961, the agency initially served as a planning and coordinating body for the major transportation agencies in the region. Its functional scope expanded in 1971, not in response to pressures from within the region for a broad-gauged planning body, but because Washington steadily increased the list of grant programs covered by comprehensive planning and review requirements.[71]

Despite its functional expansion, Tri-State remained heavily skewed in the direction of its original transportation mission. Throughout the 1970s, five of the nine state officials on the commission were from transportation agencies, as were three of the five federal members.[72] The Port Authority has been closely involved with Tri-State from its beginnings. A top Port Authority official was "loaned" to Tri-State at the outset to organize the new agency as its first executive director, and the Port Authority has always been represented on the commission by a nonvoting member. Tri-State's top staff also reflects its transportation origins. Its executive director from its founding to 1978 was a transportation planner, as were many of his deputies. Inevitably, Tri-State's general orientation has reflected its initial tasks, the interests of its dominant commissioners, and the perspectives of its staff. As a result, Tri-State has naturally tended to look at the region through the prism of transportation needs and facilities.

Tri-State's perspective also is strongly influenced by the dominant role of state officials on the agency. The commission was created by the states, and from the beginning it has primarily served state interests—and particularly those of their transportation agencies. Nine of the 15 commissioners are state

[71] The agency was renamed the Tri-State Transportation Commission in 1965 following the passage of enabling legislation in the three states. Six years later its name was changed to the Tri-State Regional Planning Commission to reflect its broadened functional scope over water and sewer grants.

[72] The five state transportation officials included the heads of the three Departments of Transportation, the chairman of the Connecticut Public Transportation Authority, and the chairman of the Metropolitan Transportation Authority. The three federal transport officials were the regional directors of the Federal Aviation Administration, the Federal Highway Administration, and the Urban Mass Transportation Administration.

officials, and all but one of the local members is a gubernatorial appointee.[73] Tri-State's agenda is set largely by the states, the chairman of the commission has always been a state official, and state representatives dominate the agency's executive committee. Discussions within Tri-State typically are framed in terms of state interests, priorities, and objectives. From the beginning, state officials on Tri-State have functioned almost exclusively as representatives of their agencies and their states. Given the structure of the commission—five members from each state, with voting arrangements requiring that a majority of each state delegation agrees with a proposal—all of the commissioners tend to think of themselves primarily as members of state delegations, whether they are state officials or not. Because of this structure the commission functions essentially as a logrolling body, with almost all decisions made on the basis of an implicit agreement that "you back my plan and I'll back yours."[74] As a result, Tri-State has reinforced the major political divisions of the region rather than mute them with an areawide perspective.

Within this framework, Tri-State's staff has primarily served the states rather than the abstraction called the "region." The commission's work is almost entirely derivative, reflecting the development goals and particularly the transportation-oriented priorities of its dominant members. The staff maintains a low profile, emphasizing its technical role and seeking to avoid controversy and publicity. Staff work is long on data, and short on analysis and recommendations. As the Regional Plan Association notes, "the Tri-State staff performs like a consulting firm, primarily providing data and responding to study requests of state and federal agencies. They seldom take the initiative to raise hard issues for Commission consideration, and little of their research reaches the public."[75] Tri-State's basic regional development guide has been characterized as "a vague mixture of what will happen and what should happen [which] masks rather than illuminates the critical issues."[76] Until the late 1970s, public attention rarely was directed to Tri-State's plans or reports; hearings were not held on its proposals; few reporters or group representatives attended meetings; and many major regional issues—such as the fourth jetport controversy—never came before the commission.

Tri-State also is constrained by the pervasive fear of regionalism discussed earlier in the chapter. An effort by the commission to play the independent planning and development role advocated by the New York Times and the Regional Plan Association would be opposed by suburban officials, local private interests, and their political representatives in Albany, Hartford, and Trenton. A case in point is suburban reaction to Tri-State's cautious efforts in the 1970s to comply with federal requirements that each metropoli-

[73] The exception is the chairman of the New York City Planning Commission, who is an ex-officio member. This official also is the only local representative among New York's five commissioners.

[74] Michael Sterne, "For Planning Purposes, L.I. Wants to Be a Breakaway Province," New York Times, April 9, 1978.

[75] Regional Plan Association, Implementing Regional Planning in the Tri-State New York Region, A Report to the Federal Regional Council and the Tri-State Regional Planning Commission (New York: 1975), p. 4. See also Regional Plan Association, "Report to the Three Governors and Legislatures on Official Regional Planning in the Tri-State Region" (New York: December 7, 1977).

[76] Ibid., p. 24; see also Tri-State Regional Planning Commission, Regional Development Guide (New York: 1968), passim.

tan area develop a comprehensive housing plan that addressed the needs of low-income families. Tri-State's effort was typical of its activities—low key, research oriented, and developed with little publicity.[77] But the suburbs reacted adversely, expressing fear that low-income families would be dispersed from the older cities under some kind of regional housing plan. On Long Island, these fears fueled the demand for separation of Nassau and Suffolk counties from Tri-State, a demand which found a sympathetic audience among the two counties' state legislators and with New York's Governor Hugh Carey, who was eager to please voters in the state's two largest suburban counties. In 1979, Tri-State's critics won a partial victory. The Long Island Regional Planning Board was designated in place of Tri-State to review most federal grant applications for Nassau and Suffolk counties, with only those Long Island projects deemed by the state as having broader regional impact to be reviewed by Tri-State. And in 1980, a strong movement developed in Connecticut to withdraw from Tri-State.

The limited role of the Tri-State Regional Planning Commission in the 1970s underscores the comparative advantage of functional over coordinating agencies in terms of influencing development. Lacking resources, autonomy, and a clearly defined mission, Tri-State has been reduced to monitoring trends and processing paper—once decisions are made by functional agencies in the region—so that federal planning and review requirements can be met.

Tri-State's weaknesses also underscore the importance of the ability to concentrate resources. Tri-State has broad areal and functional scope, yet it cannot bring much influence to bear on development. Important limitations are found in its lack of formal independence, its dependence on federal and state grants, and its complete absence of control over land use. Skillful leadership might have overcome some of these shortcomings by dramatizing the agency's role and proposals. But Tri-State's leadership has been provided by its dominant state commissioners—who have sought to restrict rather than expand the agency's independent role, and who have utilized Tri-State in part to serve the commissioners' own state-agency needs. Consequently, Tri-State is left only with planning skills to go with its broad but shallow functional and areal scope, a combination which generates a great deal of paper but very little independent impact on the pattern of development in the New York region.

[77] The housing plan attracted more public attention than most Tri-State programs, in part because of the sensitivity of the question of dispersing low-income housing, and in part because the Coalition for an Equitable Region (a group of civil rights and fair housing organizations led by Suburban Action Institute) publicly urged Tri-State to play an active role in securing compliance in the region with the Housing and Community Development Act of 1974 and other federal laws.