Machiavelli (1469–1527) and the Court as Artifice

We have begun to see better the complexity and ambiguity of social allegiances in Renaissance Italy. I shall now turn to the telling case of Machiavelli in order to show that this so consistently Florentine observer of human behavior is no exception to the fact that even in the most bourgeois environments the aristocratic ideologies that had dominated medieval literature and thought continued to affect perspectives and judgments.

Castiglione's perception of moral values in the world of politics has often been contrasted with Machiavelli's. Patently, Machiavelli's “realism” clashes with his contemporary's idealizing will to form a “perfect courtier” who embodied all that was most admirable and morally respectable in a member of the governing élite. For Machiavelli, we all know, the ordinary moral virtues are more a hindrance than a help to effective political action. Although the well-endowed statesman is conscious of the need to appear virtuous, he is able and ready to depart from moral rules when it is expedient to do so, since he aims not at the good but at the useful. Castiglione was not prepared to see how the good and the useful could be separated. But more relevant for us is how, beyond personal attitudes, both writers mirror the reality of a shattering crisis, involving the agonizing realization that the fragmented individualism of Italian political behavior had been a high price to pay for the splendors of the Renaissance. When foreign armies supported by socially unified national states appeared on the scene, the impossibility of a common policy among the Italian states spelled general ruin. The spectacle of men in unstable governments scrambling for improvised means to save their skins and privileges in the wars of 1494–1559 revealed not only the weaknesses of social and political structures but also the decisive nature of the basic moral imperative: the fateful choice between “good” government in the interest of all subjects and expediency in preserving personal or group privileges.

Both Castiglione and Machiavelli had to face the alternative of justice or power, deep honesty or hypocritical preservation of form, virtue as moral value or “virtue” as, in Machiavelli's peculiar acceptation,

efficient inner energy. Along with the traditional virtues of private morality, the “curial” ethic was now revealing more clearly than ever both its relevance and its profound ambiguity. The questions and the choices were: leading or seeming to lead, governing or oppressing and exploiting.

The “Florentine secretary” was particularly disinclined to appreciate the role of the social layer that made up the courts. As a true citizen of bourgeois and republican Florence, he did not hesitate to define the gentiluomo as one who lives abundantly off revenues without work, “senza fatica”; hence he is inherently outside that true “vivere in civilitá” that Machiavelli identified with the free cities, and is particularly dangerous when he possesses castles and dominates working people who have to obey and serve (Discorsi 1.55).[69] That “vivere senza fatica” that irked Machiavelli as parasitism unwittingly echoes Castiglione's image of the gentleman whose most impressive behavioral feature is grace in concealing his artfulness, so that he seems to do whatever he does without effort and almost without thinking: “senza fatica e quasi senza pensarvi.” Besides being a supreme mark of elegance, that easy manner was also a correlative of “living without effort” on the economic level. The very abstractness and unproductiveness of knightly games in the literature of the romances was a necessary sign of the knights' “nobility”—not quite without effort, to be sure, but without “use.” Even in the epics there were as many tournaments and games as real battles.

To Machiavelli, military exercises were justifiable neither as elegant games nor as a form of superior service to God, but only as necessary means to political ends—a shift that even the Church was compelled to accept. Hence his little regard for the usefulness of the knightly class extended to the military sphere, where he held infantry more valuable than cavalry. Compare, besides his Arte della guerra, Discorsi 2.18, “come si debba stimare più la fanteria che i cavagli,” where he blames the condottieri for a special interest in keeping armies of horsemen and, typically, appeals to the Roman model, where infantry had the major role. He cites the modern example of the battle of July 5, 1422 at Arbedo near Bellinzona, where Carmagnola, acting for Filippo Visconti, managed to prevail against the Swiss infantry only after dismounting all his horsemen.

Just as he distrusted courtiers, noblemen, and knights, Machiavelli appreciated the potential virtues of “the people” (la moltitudine, he says, indiscriminately) in terms as explicit as were ever heard before or

long after. One of his most rewarding essays, Discorsi 1.58, is titled “La moltitudine è più savia e più costante che uno principe.” There he takes a firm stand against public opinion, “contro alla commune opinione,” including, mind you, the hallowed authority of his Livy, by protesting that the people are more prudent, more stable, and of better judgment than the prince: “dico che un popolo è più prudente, più stabile, e di migliore giudizio che un principe.” They are also more reliable in their choice of elected public officials, usually worthier men than the choices of absolute rulers: “Vedesi ancora nelle sue elezioni ai magistrati fare di lunga migliore elezione che un principe.” The people will never be persuaded to put in office a corrupt and infamous person, something princes do easily. In sum, popular governments are better than despotic ones: “sono migliori governi quegli de' popoli che quegli de' principi.” If, as was the thesis of Il Principe, princes are better at organizing new states, popular governments are superior at maintaining a state once organized: “se i principi sono superiori a' popoli nello ordinare leggi, formare vite civili, ordinare statuti ed ordini nuovi, i popoli sono tanto superiori nel mantenere le cose ordinate.” The superior wisdom of the popolo is reaffirmed in Discorsi 3.34. We have come a long way from the hateful distrust of the vilain: even if Machiavelli's close paradigm was bourgeois Florence, which did not include peasants as citizens, his universal model was republican Rome, with plebeians a majority among the voting population.

All this notwithstanding, it is particularly interesting in our context, and it may come somewhat as a surprise, that in a literal sense Machiavelli's ethical framework owed more to the courtly tradition than to the classical and Christian canons. Analyzing the virtues that are profitable to the prince in the ethical section of Il Principe (chaps. 15–24), he criticizes above all the notions of liberalità (all of chap. 16), generosità, and lealtà. The choice and sequence of qualities should have a familiar ring to us. When Machiavelli advises the prince to be a “gran simulatore e dissimulatore” (chap. 18), we are reminded once again of the familiar courtly environment, including the literary one of Tristan.

Machiavelli's review of the prince's moral traits begins with this listing (chap. 15):

alcuno è tenuto liberale, alcuno misero . . . ; alcuno è tenuto donatore, alcuno rapace; alcuno crudele, alcuno pietoso; I'uno fedifrago, I'altro fedele; I'uno effeminate e pusillanime, I'altro feroce et animoso; I'uno umano, I'altro superbo; l'uno lascivo, l'altro casto; l'uno intero, l'altro astuto; l'uno duro, l'altro facile; l'uno grave, l'altro leggieri; l'uno relligioso, l'altro incredulo, e simili.

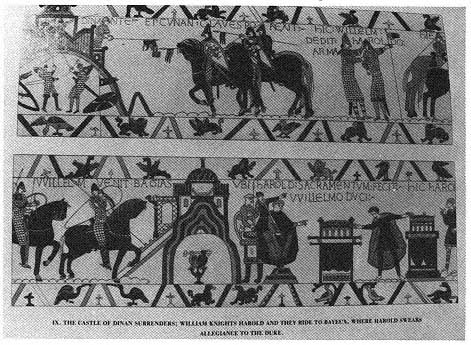

1–2.

William of Normandy Knights Harold of England; The Battle of Hastings: details

(sections 21 and 58, last) of the Bayeux tapestry (ca. 1073–1083).

Courtesy of the Town of Bayeux.

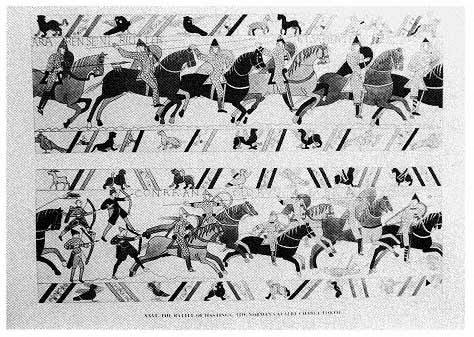

3.

Ruins of Castle Aggstein on the Danube, Austria. A point of encounter for many

troubadours.

Courtesy of Austrian Tourist Office, New York.

4.

Imperial Palace in Goslar, Germany.

Courtesy of German Information Center, New York.

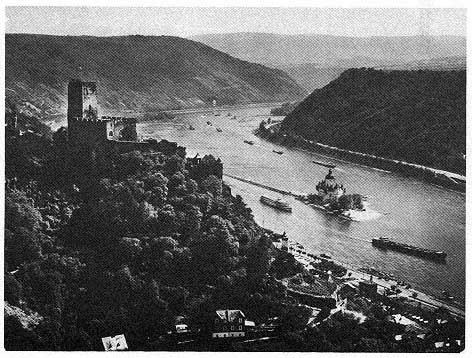

5.

Castle Gutenfels on the Rhine.

Courtesy of German Information Center, New York.

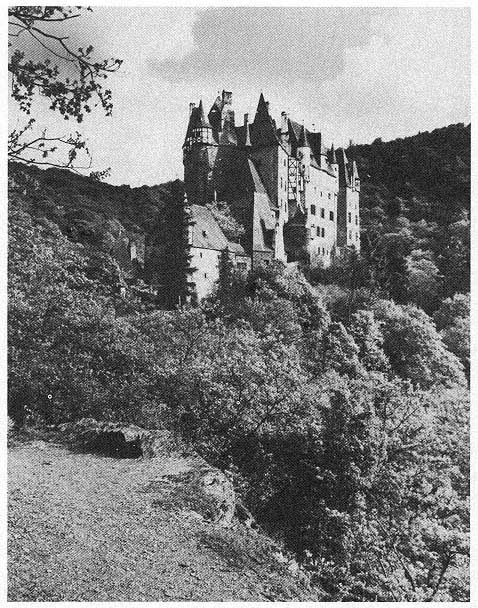

6.

Elz Castle, near the Moselle River.

Courtesy of German Information Center, New York.

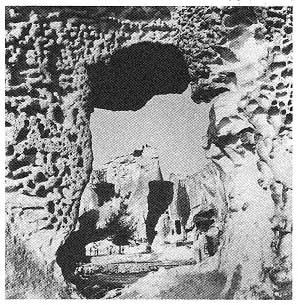

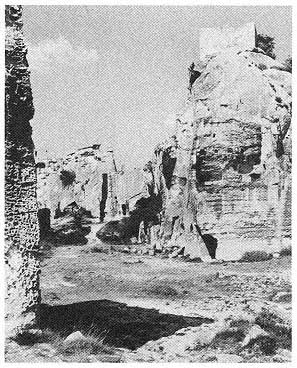

7–8.

Two views of ruins of Les Baux-de-Provence, a leading

Provençal feudal court carved out of the rock in the

thirteenth century, destroyed by order of Richelieu

as a focal point of feudal resistance to the centralized

monarchy.

Courtesy of French Government Tourist Office, New York.

9.

Giant Roland in front of Bremen City Hall. Erected in 1404 by the burghers in defiance of

the archbishops' authority, using chivalric ideology as a symbol of communal freedom.

Courtsey of German Information Center, New York.

10.

Jan van Eyck (fl. 1422–1441),

The Last Judgment. Tempera and

oil on canvas. The angel-judge

appears in the garb of a knight.

Courtesy of the Metropolitan

Museum of Art, New York,

Fletcher Fund, 1933 [33.92b].

11.

Pol de Limbourg, The Fall of the Rebellious Angels

as knights in armor. Les très riches Heures du Duc de

Berry, Musée Condé, Chantilly. Courtesy of Musée

Condé/Art Resource, New York.

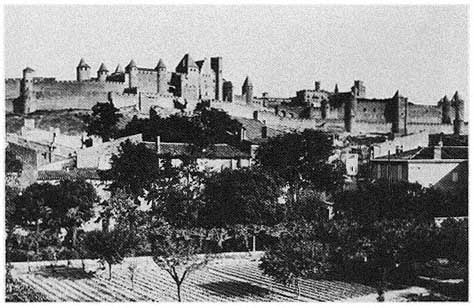

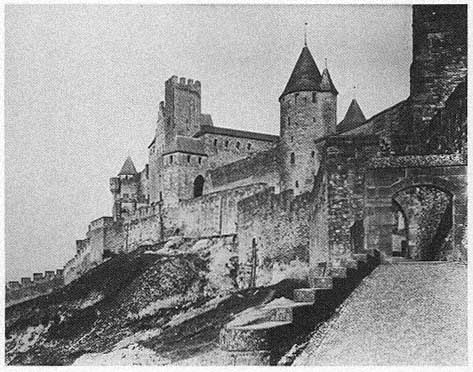

12–13.

Two views of Carcassonne. Outstanding example of medieval military architecture and

planning of a fortified town that coincided with the castle and an extended lordly court.

Courtesy of French Government Tourist Office, New York.

14.

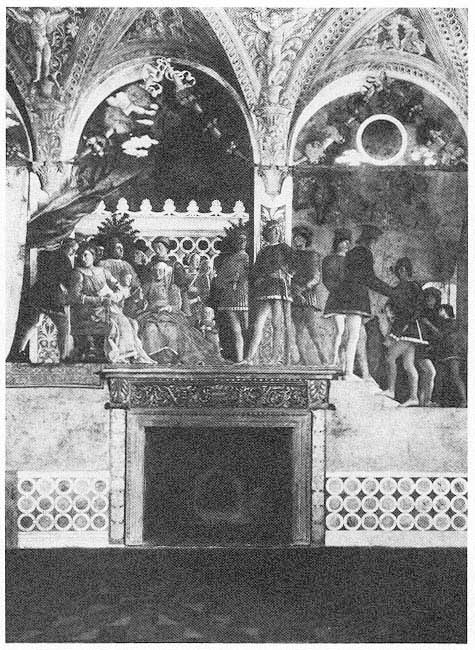

Camera degli Sposi, frescoes by Mantegna, with Ludovico Gonzaga consulting his

secretary Marsilio Andreasi (1465–1474). Ducal Palace, Mantua.

Courtesy of Scala/Art Resource, New York.

15.

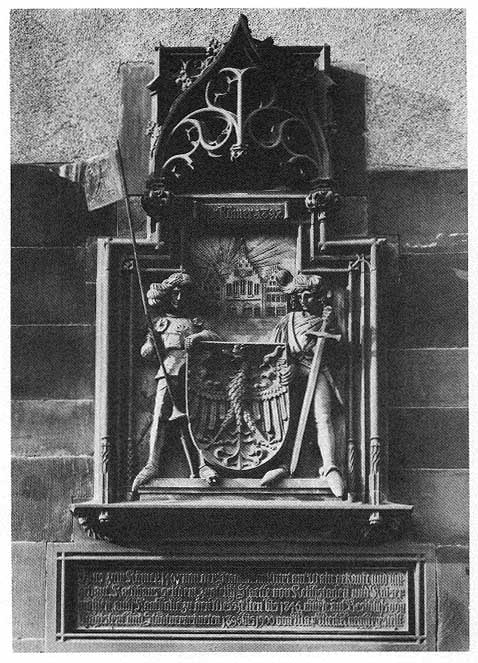

Knights in the shield of the City of Frankfurt on the Römer, 1404.

Courtesy of German Information Center, New York.

16.

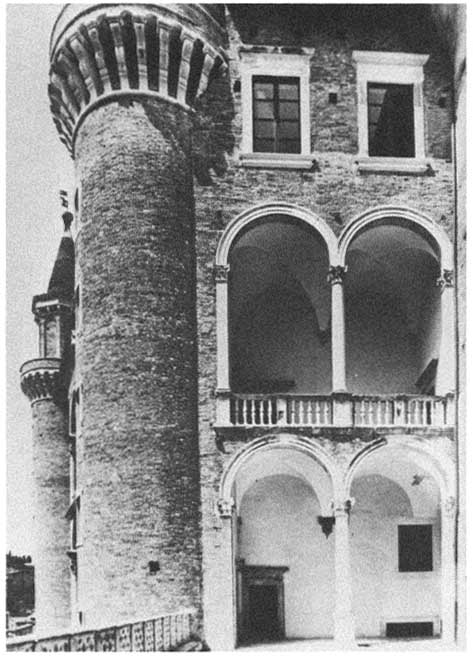

Corner of Urbino Palace, built under Federico da Montefeltro, ca. 1480? Note blending of

medieval and Renaissance features.

ANSA photo from Italian Cultural Institure, New York.

17.

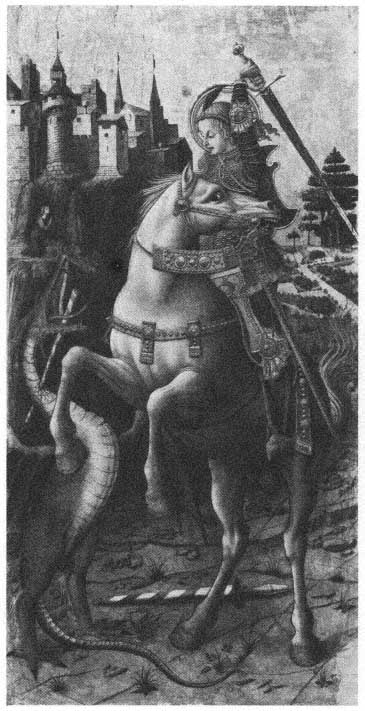

Carlo Crivelli, St. George and the Dragon. A saint i knightly garb,

or a saintly knight: anothr example of the coupling of the religious

and profane.

Courtesy of the Isabella Stewart Gardener Museum, Boston, and

Art Resource, New York.

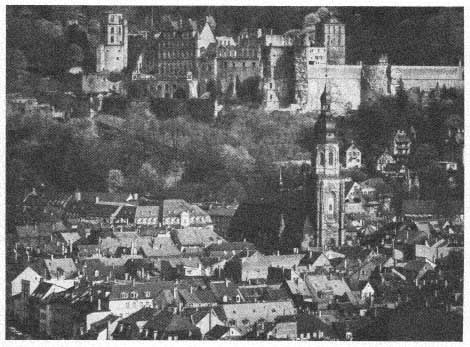

18.

Castle of Heidelberg. Courtesy of German Information Center, New York.

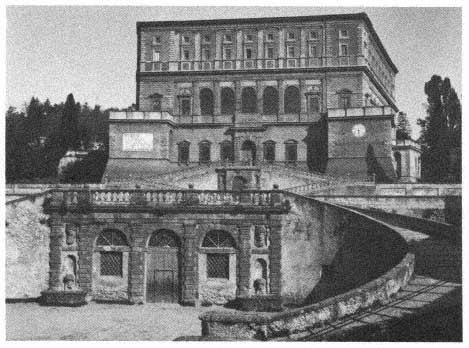

19.

Jacopo Vignola, Palazzo Farnese (1550–1559), Caprarola (Viterbo).

Courtesy of ENIT , Italian Government Travel Office, New York.

20.

Palazzo Farnese, Caprarola, Sala dei Fasti. Pius III and

Charles V in battle against the Lutherans.

Courtesy of ENIT , Italian Government Travel Office, New York.

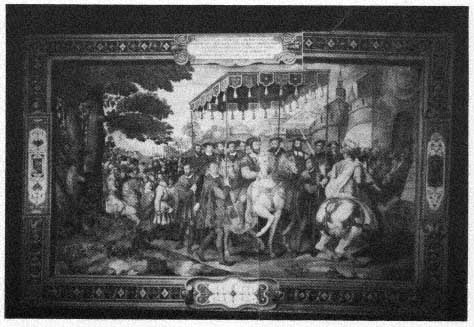

21.

Palazzo Farnese, Caprarola, Sala dei Fasti. Francis I welcoming in Paris the Emperor Charles

V accompaind by Cardinal Allessandro Farnese (Taddeo Zuccari and helpers, 1562–1565).

Courtesy of ENIT , Italian Government Travel Office, New York.

22.

Lorenzo Bregno, St. George and the Dragon, from the facade of Buora's Dormitory, Isola

di San Giorgio Maggiore (Venice).

Courtesy of Giorgio Cini Foundation, Venice.

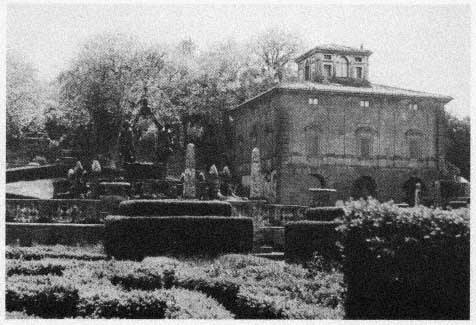

23.

Villa Lante, Bagnaia (Viterbo).

Courtesy of ENIT , Italian Government Travel Office, New York.

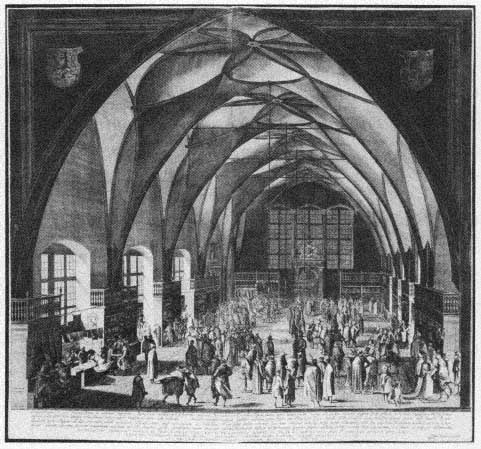

24.

The Great Hall of the Hradshin Imperial Castle, Prague, engraving by Aegidus Sadeler,

1607. The court as a center of wide-ranging socail and even commercial activities, including

trading in art works.

Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Harris Brisbane Dick fund,

1953 [53.601.10(1)].

Is this not a list of chivalrous qualities, positive and negative? It seems clear that Machiavelli did not have in mind some moral treatment of classical or Christian virtues but one of the kind that would be at home ina “mirror of princes” based on the chivalrous ethic.

Let us now take another look, reordering the pairs which Machiavelli inverts five times. He opposes liberality to miserliness, generosity to thievery, pity or mercy to cruelty, loyalty to treachery, manly spiritedness (Fr. franchise ) to duplicity (a courtly though not a courtois virtue), indulgence to hardness, dignity to plainness, and respect for religion to indulgence to hardness, dignity to plainness, and respect for religion to irreverence. The “great soul” that is made to loom large among the valuable strategic qualities (chap. 21) derives from both classical and medieval ethics, as we have observed, and Ferdinand the Catholic is declared to be its most striking example. The reference to greatness of character or soul that was implied in the animoso (contrasted to pusillanime ) is fully developed in chapter 21, where grandezza (grande imprese, rari esempli ) is commended as a way of winning fame (egregius habeatur in the Latin title rubric) and conquering the admiration of subjects and rivals. Once again, Machiavelli had the ancient Romans in mind, but the belligerent policies he regarded as a sign of vitality in the state and an almost biological law of politics had been a trademark of the chivalric ethic. Aristotle's megalopsychia was destined to play a continuous role through the Middle Ages and humanistic education as well, including, in the new context of militant Christianity at the service of the Church, the Jesuit schools. The ideal of magnanimity would remain part and parcel of Jesuit pedagogy, since Ignatius of Loyola (himself a heroic professional soldier before his conversion) characterized the true Christian as a militant soldier of Christ, the new miles Christi.[70] Machiavelli's heroic view of political leadership falls within this continuous tradition.

Indeed, at opposite poles, as it were, both the secular thinking of a Machiavelli and the planning of educational patterns for the Counter-Reformation disclose the presence of the combined ideologies of chivalry and courtliness. As an eloquent example of the latter I shall mention only the case of the most important college for the nobility in Italy, that of Parma. The Duke of Parma, Ranuccio I Farnese, took pains to ensure the functioning of the Ducal College for the Nobility (1601) as a bulwark of his policies of firm orthodoxy within a program of outspoken loyalty to the Roman Church and to Spain. It is interesting that in so doing he spelled out the guiding principles for his college in terms of the ideologies of chivalry and courtliness. Its pupils were to be in-

structed not only in piety and letters—which was also the explicit program of all Jesuit educational institutions—but also “in those other exercises that are proper to the Nobility and necessary to Knights,” namely dance (a healthy sport and a social grace), mathematics (for military engineering), fencing (for the use of arms in the service of God), and horseback riding.[71] The College was soon entrusted to the Jesuits (1604–1770).

The presence of the courtly ethic in Machiavelli's oeuvre extends beyond the Principe. Besides the image of the virtuous prince using the art of “the fox” (like Caesar Borgia in Il Principe, chaps. 7 f.), the theme of astuzia, analogous to the familiar “cunning” of successful courtiers and such devious courtier/lovers as Tristan, conspicuously invests the whole plot and characterization of the Mandragola, a triumph of unscrupulous pursuit of personal ends.[72] In a properly political context, Discorsi 2.13 and 3.40 treat fraude (fraud) as advisable strategy rather than forza (force) in appropriate circumstances, especially at war, when one deals with an enemy (“parlo di quella fraudechesi usa con quel nimico che non si fida di te,” 3.40): again, the fox rather than the lion. Discorsi 3.30 confronts the problem of avoiding envy (invidia ). Three chapters of the Discorsi (1.28–1.30) deal extensively with the question of loyalty and attendant gratitude that recalls the feudal tenets of mutual service and response to favors. In 1.29 the modern example is again Ferdinand of Aragon, who in 1507, suspicious of the acquired reputation and power of his victorious captain, Gonzalo Fernández de Córdoba (Consalvo di Córdova), confined him to Spain instead of rewarding him for his Neapolitan victories against the French. Machiavelli presents the case in a feudal mode of reasoning, political actors being moved by personal considerations rather than by impersonal ones. The following chapter 30 addresses the question of ingratitude by analyzing what amounts to the change from feudal to absolute government (translated into our code, ingratitudine is lack of proper reward, or withholding of it without good reasons). The prince must prevent a subordinate from gaining glory for himself: he can do so by participating personally in the campaigns. A victorious captain, in turn, must no longer expect grateful reward (as his knightly predecessors did). He must either abandon the army, to avoid suspicion of ambitious aims, or be bold enough to hold onto his conquests for himself. We have gone from feudal decentralization and delegation of power to a radical individualism of private wills and interests, yet the new background is the Roman type of state, with impersonal relationships through law and office, instead of

personal privileges and rights. The chivalric mentality, in other words, still appears in the background of Machiavelli's reasoning on moral issues, but it has been left behind for a new mental environment of calculated realism.

Machiavelli's tenacious republicanism in the face of his deep realization that the days of liberty were numbered stands out even more clearly when we note the readiness of leading citizens to cooperate with the Medici in institutionalizing absolutism. Typically, Ludovico Alamanni authored a cynical discourse of advice to the Medici ruler on how to corrupt republican leaders by turning them into subservient courtiers, so as to cut them off from any community of interests with the governed. It was precisely what Duke Cosimo I formalized by instituting the Order of Santo Stefano (on which more later). After the leaders have been attracted to the new court as servants of the new prince, and thus converted and bound to his destiny, Alamanni suggests that they will not only renounce the ideals of the republic, but will never again aspire to popular favor as champions of the subjects' common interest.[73]

The preceding has shown how, leaning on the virtues of a new courtesy, the ideals of chivalry found a fresh operating ground in both lay and ecclesiastical courts of the Italian Renaissance, while they remained part of the mental processes whereby even a republican-bourgeois observer like Machiavelli could frame his own analysis of the ways to achieve and maintain power.