10—

From Hard Money to Branch Banking:

California Banking in the Gold-Rush Economy

Larry Schweikart and Lynne Pierson Doti

If Americans associate any event with the early history of California, it is the Gold Rush. While the impressions of most people are that the Gold Rush "came and went," more or less, with little lasting legacy other than to alert outsiders to the vast wealth to be found in California, the economic development of the state actually took on much of its early form based on the experiences of the Forty-niners. Banking and the financial sector, in particular, evolved in often distinctive ways because of the gold-rush economy. More important, the abundance of gold on the West Coast provided an interesting test case for some of the critical economic arguments of the day, especially for those deriving from the descending—but still powerful— positions of the "hard money" Jacksonians.[1]

By the time banks appeared in California, commercial banking was well established east of the Mississippi, and had made inroads in Missouri.[2] The process by which banks came into existence was common, but not uniform: usually a merchant or freight agent would accept deposits from local entrepreneurs who wanted a safe storage for their money or gold, exchange drafts written from out-of-town companies and pay out gold, and often extend credit to valued customers. The combination of accepting deposits, exchanging drafts, and making loans endowed those merchants with the essential functions of banks. When their business reached such a level that it equaled or surpassed their mercantile or freight activities, they often sought a banking charter from the state legislature, although not all "bankers" had charters. The charter usually empowered the banker to issue paper money, called "banknotes" or simply "notes." Money thus circulated, and competed, against other privately issued money by relying on gold as a standard of measurement, since all notes had to be convertible into gold at some point. More often than not, however, the real determinant of a note's value rested on its reputation—or, more precisely,

A row of solid brick banks lines the west side of Montgomery Street in a charming

watercolor executed in the early spring of 1851 by an unidentified French artist. Visible,

left to right , are the offices of the San Francisco Savings Bank, E. Delessert & Cordier,

James King of William, and, across Commercial Street, the bank of B. Davidson, agent

for Messrs. Rothschild. The concentration of so many financial institutions had, the

previous year, led a newspaper to declare that "this beautiful street may well be called

the Wall Street of San Francisco." California Historical Society .

that of the issuer—and many banks reflected the apparently paradoxical condition of having low reserves of gold and yet high levels of soundness and solvency. Of course, that paradox was understood if it was kept in mind that instability was related to a weak reputation more than to low reserves of gold.[3]

When banking appeared in California, the debate over whether banks should be prohibited from issuing notes at all was decided in favor of the private note. The Panic of 1837 had made several states hostile to banks, with Arkansas and Wisconsin actually prohibiting banks (as Texas later would do). Of course, note-issuing banks still appeared, generally under the inventive title of "Marine and Fire Insurance and Banking Company," or "Railroad and Banking Company." Governments found they could not eliminate the demand for banks—or paper money—and of-

ten, "bankless" states, such as Iowa in the 1850s, found that the business they lost to neighboring states caused them to rethink their inflexible positions.[4] California, therefore, by 1849, had plenty of evidence about what worked and what did not work when it came to bank structure. Yet none of the experiences of banks in other states had the key ingredient that California possessed: abundant gold, capable of sustaining a metallic currency.

The discovery of gold on January 24, 1848, at a mill owned by John A. Sutter sparked a stampede to the mines of northern California. Likened to a "hysteria" or to a dam bursting, the Gold Rush brought in thousands of people from everywhere in the world, and with them came a new outlook on life: Mark Twain facetiously reported haircuts going for $1,000, and yet people "happily paid it, knowing that we would make it up tomorrow."[5] Gold poured out of the mines and streams in large enough amounts to run any economy, and indeed, "if a metallic-based economy could survive anywhere, if metallism, as the Jacksonians preached, was a desirable alternative to banks and paper money, then it should have taken root . . . in California."[6] According to the Jacksonian principles of banking, there should have been little need for bankers, the much disparaged "middlemen." Instead, the California experience demonstrated the critical role that financial intermediaries play in evolving market systems, even when a suitable "money" was widely available.

Prior to the Mexican-American War in 1846, California lacked banks altogether and had a chronic shortage of paper currency and minted coin. Indians had devised the earliest common currency of the state, meticulously carved round pieces of shell with holes in the center so the "coins" could be strung on long leather thongs to create an early wallet. When the Spaniards arrived and began trade, the strings of coin traded at the rate of a yard to a Spanish dollar. Still, from the founding of the first mission in San Diego in 1769 until Mexican independence in 1821, most trading was by barter. As the missions were closed by the Mexican government after 1833, the economy focused on a few hundred large cattle ranches. These ranchos were basically self-sufficient empires with little need for banks or money. Cowhides, dry, flat, and stiff enough to sail like Frisbees off a cliff, were known as "California dollars."[7] Tallow, hides and furs, classed under the general moniker "fur money," had been a constant in the frontier fur trading areas from the Mississippi to the Rockies, and the Bank of St. Louis, on the main route east from the trapping grounds, accepted pelts and issued money on that security.[8] California cattle hides, also called "California Bank Notes," circulated as a popular form of early money.[9] As an example, Captain William Davis of the USS Eagle recorded a transaction in which he sold some goods to Friar Mercado of the Santa Clara Mission in 1844 and received two hundred hides.[10] Despite the obvious fact that a skin-based currency demanded little in the way of safes or vaults, Davis claimed himself as the one to have brought the first safe to California in 1846.[11]

After the state was abruptly wrested from the control of Mexico by the war in 1846, the American population slowly increased. Settlers following the Oregon Trail to the Northwest veered south to find the fabled lush and massive Central Valley between the mountains and the coast. Soldiers passing through Monterey, San Diego, and inland long after remembered the ideal climate and the vast amount of empty land. Some returned, and some influenced others to settle in California. The economy began to develop markets as many of the ranchos were subdivided and the smaller landholders were less self-sufficient, and these markets created a need for money. American dollars brought by settlers became the most common, though still rare, money.

As elsewhere in the West, the local residents expressed more of a concern for the scarcity of currency and coin than for the absence of banks. As two historians of the subject concluded, the "cry 'There is no money in Kansas' might well have described the situation in neighboring plains states as well," and also in California, at least before the discovery of gold.[12] Of course, everything changed when James Marshall, on January 24, 1848, presented a sample of ore from the South Fork of the American River to John Sutter, a Swiss-born adventurer who had hired a group of Mormons to construct a sawmill for him. Quickly, the California economy was changed: by summer, reports of gold had drawn hundreds of people from other parts of California to the region, and then, as news of the discovery spread, thousands of prospectors and miners arrived at San Francisco, from which they would take boats up the Sacramento River, then walk uphill to the gold fields some forty miles from Sacramento. There, they found gold in impressive—indeed, absolutely phenomenal— amounts. Between 1848 and 1860, according to one estimate, gold exports from California topped $650 million at $16 an ounce.[13]

San Francisco reflected the boom in its population, which had stood at barely 150 in 1846, only to swell to 50,000 a decade later. Each new immigrant seemed to add to the news traveling back home that anyone could get rich in California, and regular reports by field agents of express companies, such as William Rochester of American Express in 1851, contributed to the excitement. That year, gold production rose from $41 million to $76 million, leading one resident to comment, "Gold never was known so plenty in San Francisco as this season."[14] Yet despite the abundance of gold, the United States did not open a mint in San Francisco until 1854, meaning that the scarcity of coin persisted amidst an ocean of gold. All customs had to be paid in U.S. coin, which led to hoarding of the few pieces of metallic currency that existed.[15]

Using gold ore or dust for daily business transactions proved difficult because the measurement and valuation of gold in such forms constituted an inexact science, even for the experienced. Gold as it came from the mines was rarely pure. Even nuggets could contain spots of other metals or dirt, and the more common "dust" really consisted of several materials mixed together. Dealers usually weighed the dust

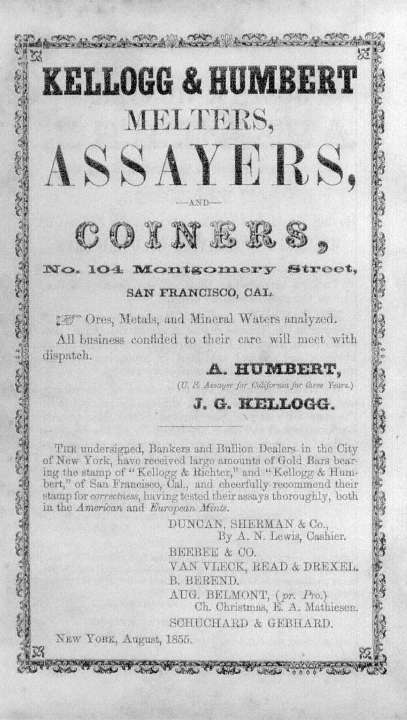

An advertisement from the San Francisco Business Directory of 1856 for

Kellogg & Humbert, located at 104 Montgomery Street. In addition to

providing assaying services, the firm produced gold bars and operated a

private mint. California Historical Society, FN-30964 .

to ascertain value, and an experienced assayer prided himself on his ability to determine by color exactly where a particular batch of gold had been found.

The difficulty of determining the purity of gold as it came from the mines was only the first problem of using gold as money. Since value depended on weight, every party to a transaction wanted scales. Not only did a miner on a shopping trip have concerns about carrying his leather pouch of gold along, but he had to bear a second pouch containing a miniature set of scales and weights. Differences in calibration between buyers' and sellers' scales placed a premium on negotiation skills. No wonder at least two dozen private mints operated in California.[16] Those mints charged customers to refine their gold and exchange it for coins stamped with the mint's verification of weight and purity. Miners worried about protecting their gold, too, after it was mined and especially when they were in town for their nights out after replenishing their supplies.

A dependence on metallic money presented another problem for miners and merchants in California. At first, there were no local sources of mining equipment. Clothing, blankets, flour, and whiskey all had to come from the East Coast or another distant location. To restock the stores, someone had to travel back with the gold to make the purchases. Many miners also wanted to send payments back east or out of the country to families left behind.

Valuing, transporting, and safely storing gold all contributed to stimulating early banking functions in California. But identifying the "first bank" in California involves determining which of several banking functions or services an individual or business provided—not an easy task, considering that many of the early merchants and entrepreneurs performed most banking functions at some time or another, but seldom all functions at the same time. As late as 1847, of the 169 men who provided their occupations for a newspaper article, none listed themselves as bankers. Robert A. Parker, who later established the Parker House Hotel, was possibly San Francisco's first banker, conducting primitive banking operations from his store on Dupont Street in 1848.[17] Other firms, for example, Mellus, Howard & Co. and B. R. Buckalew in San Francisco and Dickson and Hay in Sacramento soon advertised themselves as "gold dealers," but undoubtedly exchanged drafts and took deposits.[18]

The early gold dealers had provided drafts or exchange for gold, giving the prospectors a liquid and divisible medium for a less liquid and less divisible metal or for notes from other regions that were less well known, and therefore, less reliable. Dealers purchased gold at $8 to $16 an ounce and sold it on the East Coast for $18. This operation allowed merchants and miners to pay local dealers in gold, and get drafts that could be more cheaply and easily transported to pay suppliers or family. Gold dealers then shipped gold in large shipments for sale on the East Coast. Bringing money from outside California was more of a problem, since gold or gold-

backed paper was the only locally accepted money. Exchanging local paper for out-of-town notes (called "foreign" notes, even if they originated in another California town) carried a fee—a "discount" based on distance and risk—to redeem the draft or note. An early advertisement for C. V. Gillespie, a San Francisco merchant, read "Wanted: Gold Dust at a high rate of interest for which approved security is offered," and touted loans "negotiated in Gold Dust for both long and short time, interest payable monthly, quarterly, or with the principal at maturity of engagement."[19]

Companies that shipped gold also soon found themselves in the exchange business. Adams & Co., one of the first important express companies in California, became one of the major exchange dealers prior to 1855. Likewise, in Stockton, C. M. Weber, who started the towns first express company, had built a vault and obtained a safe in 1851 for the purpose of accepting packets for storage.[20] Wells Fargo, initially in the express business and eventually also in the stage business, entered banking in California in July 1852, when it first issued certificates of exchange.[21] Familiar with the uncertainties of early transportation, Wells Fargo sent three copies with different carriers between remitters and receivers in the East and West, with the first certificate received recorded as the official transaction and paid, and the others treated as void if and when they arrived. The banking services at Wells Fargo had grown so important by 1852 that an advertisement in the San Francisco Business Directory only mentioned the express business in tiny letters, while below it, a huge headline proclaimed "Bankers and Exchange Dealers."[22] Wells Fargo's banking operations grew so fast that by 1855 the company had expanded its services to Sacramento, Stockton, and Portland, and when Wells Fargo opened its office in Los Angeles, its capital reached $1 million.[23]

A final breeding ground for early banks was the general store or merchant. Most merchants allowed reliable customers to "run a tab"—an early form of credit extension —and many already had safes to protect their own daily cash balances. It did not take long for merchants to offer space in their safes for valuables or cash, giving the depositor a receipt, which still other merchants honored or discounted against. One such merchant, Darius Ogden (D. O.) Mills in 1848 left a budding career as a bank clerk in New York to follow his brothers to California. Abandoning the rigorous life of a miner shortly after he arrived, Mills purchased a stock of goods, which he transported to Sacramento and quickly sold. The profit from this operation was so much greater than in the gold fields that Mills returned to New York, found a financial partner, and bought more goods to take back to Sacramento. After a year as a storekeeper, Mills made another trip to New York to present his business partner with $40,000 in profits from a $5,000 initial investment—in fact, Mills had acquired his first cache of goods with just $40 in cash.[24] When Mills traveled back to Sacramento in the winter of 1849-50, he left orders for a variety of goods to be shipped after him, including a large safe, which became the key feature in the new Bank of D. O. Mills.

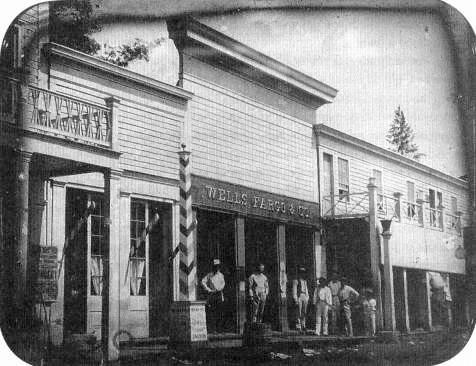

The Wells, Fargo & Co. office at the town of Iowa Hill, located near the North Fork of

the American River in Placer County, August 1855. Prospectors found gold here as

early as 1849, but it was not until five years later that miners struck rich diggings and

the camp boomed. Charles T Blake, the local agent for the famed express and banking

company founded by Henry Wells and William G. Fargo, stands in the center doorway.

California Historical Society, FN-24037 .

Whether as an express agent, a gold dealer, or a merchant, the route by which one became a banker usually involved several essential steps, not necessarily in any particular order. A would-be banker had to establish himself (there were no female gold-rush bankers of record) in a business of some type, demonstrating to customers that he could be trusted to exchange currency and gold honestly and effectively, and also presenting a personal testimony that he was successful. That image has been taken for granted by historians, but for the potential customers of the day, it represented a crucial element in convincing them to deposit hard-earned gold or currency with a merchant.

Another critical step toward becoming a banker was to purchase a safe—the path followed by Mills—which established the individual as a person to whom others could entrust money with assurances of physical safety and security. Once a busi-

nessman had gained a reputation, amassed a measure of personal wealth, and acquired a safe, the final step was to construct a building. The bank building in the Old West, like the safe and the vault, has been largely overlooked. The structure was the physical symbol of safety upon which a banker's business rested. Western bankers had used a number of innovative temporary facilities and strategies to protect money, including hiring full-time guards, placing money in boxes with rattlesnakes, and hiding real gold in waste baskets while substituting gold-painted rocks in the cash drawers.[25] Those, of course, did not satisfy the demands for a building and an iron safe, and therefore an aspiring banker made it a matter of urgency to construct a facility that not only provided physical protection of assets but also suggested to even casual observers that it was an establishment of permanence and strength. The structure itself often contained the most ornate furnishings and finest wood and brass, rivaled in a typical western town by the saloons perhaps, but by few other buildings. The preference for ornate design, rich woods, marble, brass, and other costly materials did not reflect reckless expenditures on meaningless trappings or extravagance. Rather, the building offered physical security, because a bank was inevitably located in the middle of town, "far enough away from the saloon to discourage alcohol-induced midnight pilgrimages by the bar patrons, but close enough that the next morning those same bleary-eyed (and broke) revelers could obtain more cash."[26]

Inside the bank building, an interior wall might be bordered by another business, with a stone or brick vault usually set into the wall or placed in the basement. Even if someone breached the vault, the thief would have to penetrate the safe. Early ball-safe designs utilized a large, hollow iron ball that held cash and valuables, and that rested on a square base, inside which were stored important papers and deeds. The ball was too large and heavy to carry off, and its round surface made it almost impossible to crack using the blasting powder available at that time. Ball safes soon gave way to the larger, rectangular combination safes produced by Hall Safe and Lock in Cincinnati, Ohio. Bankers tended to place the safe inside the vault, which had barred windows and doors. In this manner the artistically embellished iron box was both protected and displayed, presenting the customer a clear view of the banks chief symbol of safety.

A bank building, complete with its vault and safe, represented an investment in the community of substantial proportions, costing between $8,500 and $250,000. The investment in a building could represent as much as 50 percent of its total capital: William Ralston's Bank of California building constituted 12.5 percent of the banks initial capital, while at the Lucas Turner & Co. Bank, managed by William Tecumseh Sherman, the three-story 1854 building that housed the bank and other office space accounted for 27 percent of total capital.[27] Placing so much of a banks precious capital in a building might seem odd to modern, cost-efficient managers until it is understood

that the building constituted the most important source of advertising. In an age when many customers were illiterate or literate but unread, the bank had to transmit the message that it was safe and secure in a clear, public display: the imposing bank building.[28]

It was doubly important that a new bank have physical symbols of safety, because, in the absence of regulation, bankers had to assure customers that they protected the customers' funds. Perhaps in the most unnoticed event of western frontier history, these symbols of safety worked almost to perfection. A thorough search of the records of all states west of the Missouri/Minnesota border (not counting Texas, which was still considered "southern") reveals the total absence of bank robberies in early years. Though they became a staple in the western movie, virtually no bank robberies—or, at least, successful ones—occurred prior to the 1920s in the West. Authors have found few incidents that even come close to qualifying: a raid on a bank in Nogales, Arizona (a border town subject to bandit incursions from Mexico); a failed attempt by the Butch Cassidy gang on a Colorado bank, in which the would-be thieves used nitroglycerin to threaten hostages; and a 1912 shoot-out in Newport Beach. Otherwise, the outstanding reality of banking in the West was that symbols of safety worked exceptionally well, not only as visual reassurances of security but as deterrents to assaults on the physical capital of the banks.

Another reason the banks had to maintain an imposing physical presence in the town stemmed from the fact that while a single individual usually stood out as the banks "founder," in reality many early California banks, reflecting the regions highly transient population, were characterized by a high level of ownership instability, with partners frequently entering and leaving the businesses. Moreover, the names of California banking companies changed as often as did the partners. Consider the banking business of Dr. Stephen A. Wright, who in 1848 established the Miner's Bank out of his exchange operations. In September of the following year, he changed the name to Wright & Company, located at Kearney and Washington in San Francisco. Less than a year later, it was reorganized as Miner's Exchange and Savings Bank. A similar business, Decker and Jewett of Marysville, had started as Cunningham and Brumagin (1850), which became Mark Brumagin & Company (1854), then Decker Brumagin & Company (1858), Decker, Jewett & Paxton (1861), and after 1863, Decker, Jewett & Company. The final name, Decker Jewett Bank, lasted until the bank's closing in 1927.[29]

One exception to the typical career path, through which it was typically merchants, freight agents, or gold dealers who evolved into bankers, was Thomas Wells, a newspaper publisher (and no relation to Henry Wells of Wells Fargo) who moved to California from New England. In August 1849, Wells opened his Specie and Exchange Office, which consisted of a simple room, 15 by 18 feet, with a wooden plank counter. Nevertheless, by the end of that year Wells had emerged as the leading banker in the city, writing to his wife that deposits amounted to $132,000 and

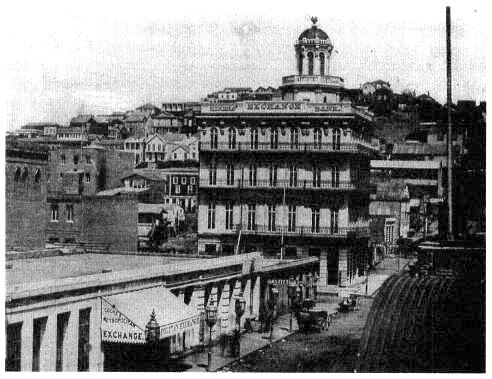

Stephen A. Wright's Miners Exchange Bank, on the northwest corner of Montgomery and

Jackson streets, was built in 1854 from designs by Peter Portois, one of the most notable

European architects to work in California during the nineteenth century. Wright, whose

banking company underwent a series of name changes in the early years, poured $147,000

into the construction of the building, a tasteful exposition of current French fashion, which

immediately became a San Francisco landmark. Above a first floor of heavily rusticated

granite blocks rise three stories of brick, plastered in simulated stonework and topped by a

towering lantern. Courtesy Bancroft Library .

that he was opening two or three new accounts every day.[30] By 1850, he had taken in a partner (who added $50,000 in capital) and started construction on a new "fireproof building," which a year later he discovered not to be fireproof, at great cost to his own health when he stayed in the bank too long during a fire. (In the mistaken assessment that "fireproof" really meant fireproof , several bankers, including James King of William, tried to sit out fires inside their supposedly flame-resistant buildings; King almost died from smoke inhalation.)[31] At any rate, Wells found that the fire at his bank had wiped out his business, for within six months his notes were protested by another company, indicating that they were not sound. Wells could not cover the bills, and placed the bank, or what was left of it, in the hands of trustees who paid off creditors at the rate of thirty-seven cents on the dollar.

Joining Thomas Wells in the banking business in San Francisco by late 1849 were at least three other banks: Naglee & Sinton (later Naglee & Company), Wright, Burgoyne & Co., and B. Davidson; and a year later three more, D. J. Tallant, Page, Bacon & Co., and F. Argenti & Co., entered into competition with the original group. Still other competitors were de facto banks that did not adopt the title "bank."

Whether these establishments were banks in name or in fact, the rapid emergence of banking businesses in California in 1849 was especially noteworthy because much of what they did was technically illegal. The delegates to the 1849 state constitutional convention (which included only one person described as a banker) had prohibited anyone from issuing paper notes or otherwise exercising banking privileges. If banking was prohibited, where did all the banks come from? How did one reconcile the presence of so much gold and so many bankers, with such clear antibanking legislation?

The California Constitutional Convention, convened in early September 1849, met concurrently with a group of private citizens who considered the "official" body illegal. In the official body's draft were several provisions related to banking, including sections 31, 33, and 36 (general incorporation and limited liability acts); section 34 (which expressly prohibited the legislature from passing a charter for a banking association, but still holding open the possibility of private "associations . . . formed under general laws for the deposit of gold and silver"); and section 35 (prohibiting the legislature from "sanctioning in any manner . . . the issuing of bank notes").[32] California had, perhaps inadvertently, accepted the then-popular notion of "free banking" without some of the features that made free banking especially effective. Free banking allowed anyone to open a bank without the express approval of the government, but often required bankers to assume liability for the loss of depositors' money. Scotland's earlier period of free banking, for example, featured double liability for stockholders if deposits were lost.[33] Far from anticipating the widespread appearance of free banking, though, the constitutional convention, wanting to spare the state from what it saw as the evils of paper money, thought that the mountain of gold upon which the state rested would by itself suffice to eliminate banknotes. That did not prevent some, such as a member of the drafting committee on banking and incorporation, from arguing in his finest Jacksonian rhetoric for providing "the strongest constitutional safeguards against the vicissitudes . . . of this monster serpent, paper money.[34] One committee member, J. M. Jones, tried to eliminate the general incorporation laws and to expressly prohibit banks, including any "associations" that accepted gold and issued receipts that might circulate as money. But others quickly countered that merchants demanded a circulating medium, and that failing to permit free enterprise in the form of banks could well jeopardize the ratification of the constitution by the public. As a result, the convention gave the legislature the power to grant charters for banking, but prohibited such banks from issuing paper money—and a second, separate passage reiterated the ban on paper

money—and accepted the general incorporation laws with limited liability. Then, as if to confuse completely the conventions intentions, the first legislature established a rate of interest at no more than 10 percent per year on loans, even as it had prohibited any "evidences of debt" (outlawing I.O.U.s). In reality, the constitution and the legislature's stipulations regarding paper money and banks already had been rendered obsolete and irrelevant by the market, which daily saw hundreds of miners exchange gold for drafts—a reality to which the legislatures finally acceded when laws were passed taxing banks on the gold dust brought in or the exchange sold , underscoring the significance of money creation as a central element of early banking.

A threat far more dangerous to California's early banks than contradictory laws was the decline in the mines' gold production after 1852. Miners needed more expensive equipment to reach the gold, as the simple pans and picks of a few years earlier no longer sufficed. From 1854 to 1855, banks in San Francisco experienced several panics, particularly when Page, Bacon & Co. failed, triggering a disastrous run. The main office of Page & Bacon in St. Louis had heavy losses on a midwestern railroad loan, but had raised sufficient gold in California to keep the office open, shipping back to St. Louis by steamer. While the gold was en route, word reached San Francisco that the St. Louis branch of Page & Bacon had folded, and the subsequent run shut down the company, as well as other San Francisco banks, including Adams & Co. and Wright's Miner's Exchange Bank. Eventually, even most offices of Wells Fargo were closed. The Daily Herald reported that "No day so gloomy has been witnessed in San Francisco since that disasterous fire of the 4th of May, 1851. Every bank was said to have suspended, and rumors of mercantile failures—most of them false, we are glad to say—came thick and heavy in the afternoon."[35] Another panic occurred when prominent San Francisco citizen Henry Meiggs, who had supplied much of the city's lumber and built Meiggs Wharf, unexpectedly left town owing $800,000 secured with forged city warrants.[36]

Meiggs's sudden departure could be traced to the constant hounding he received on his debts by William Tecumseh Sherman, later the famous Civil War general. Sherman had first come to California as a lieutenant during the war with Mexico. His nearly three years' experience was deemed adequate to make him a valuable representative of Lucas Turner & Co. of St. Louis, when that company opened a bank in San Francisco in 1853. Henry Turner opened the branch early in 1853 by renting a suitable space for $600 a month and hiring two employees. Sherman arrived to assume control in late April after a two-month trip marked by a pair of shipwrecks on the same day: "Not a good beginning for a new peaceful career," he wrote.[37] Finding the California economy still booming and business prospects good, Sherman returned home, resigned his U.S. Army commission, collected his family, and journeyed back to California to stay, at least until 1860 as he had agreed. As a manager, Sherman proved as relentless as he would later be to the Confederates. A

reading of Dwight Clarke's edited collection of letters from Sherman shows that the future general mercilessly pressured Meiggs for payments in the period prior to the latter's hasty departure.[38]

That weeding out of banks caused by repeated panics merely opened the door for other ambitious and talented men, including William Chapman Ralston, who had abandoned his steamboating career to become a Forty-niner.[39] While crossing the Isthmus of Panama, Ralston met some old steamboating friends, Captain Cornelius Kingston (C. K.) Garrison and Ralph Fretz, who wanted him to handle the Panama branch of a travel and freight business they had in San Francisco. After dealing with malarial climate, unprepared travelers, and even a major shipwreck, Ralston finally settled in San Francisco in 1854 and opened his own steamboat business, earning profits from shipping passengers and goods and amassing enough in January 1856 to open a bank called Garrison, Morgan, Fretz & Ralston. Charles Morgan and Garrison withdrew from the business in 1857. Now renamed Fretz & Ralston, the firm soon merged with dry goods merchants Eugene Kelly and Joseph Donohoe for additional capital.

During that period, Ralston invested in a variety of local industries: foundries, railroads, and dry goods firms. He also expanded to the north, allying himself with the Ladd and Tilton Bank of Portland, which brought a stern warning from Kelly. To Ralston, the reprimand constituted an opportunity to open his own bank, and he immediately rounded up some of the most prominent local citizens, including D. O. Mills. Ralston wanted his new bank to stand out as the most important in the state, and accordingly he named it "The Bank of California" (with "The" always capitalized in the title).[40] Mills became the new president, bringing to the position his reputation, while Ralston took the daily management job of cashier, deciding the investments and loans that the bank would make. When the bank opened on July 1, 1864, its charter specifically listed its business as banking, the first allowed under an 1862 revision of the state's constitution. The Bank of California thus became the first incorporated bank in California, drawing its customers and investment profits primarily from the increasingly successful Comstock silver mines.[41]

Silver mining offered tantalizing opportunities for wealth. The silver veins dove deep into the mountains, and became accessible only by digging expensive shafts, which required extensive capital. Silver miners might easily discover a vein of the blackened metal near the surface, but the pursuit of silver veins required deep mines with reinforced tunnels, ore cars and rails, and pumps and blowers to keep the miners alive, as well as elaborate mills and separators to process the ore. A lively market for mine stocks developed as people realized that capital invested in a mine might not pay off for years or make one rich in a day. Silver mining launched the Pacific Coast Stock Exchange. It also stimulated the production of timber to reinforce deep mines, and railroads to transport timber from the Sierra Nevada to the desert area

of Virginia City. Of course, mining constituted a volatile business, with the constant threat of cave-ins, floods, or fires.

It did not take Ralston long to appreciate the close relationship his bank had with the fortunes of the mines: when a miner's pick hit a subterranean water vein and flooded the shafts, mining stocks plummeted and Ralston's correspondent bank in Virginia City failed. That episode served to convince Ralston that he needed his bank to have its own branch in Virginia City, prompting him on the recommendation of a friend to hire William Sharon. When Sharon arrived in Virginia City, he dove into the thorny problem of the long-term profitability of the Comstock Lode, visiting chilly caverns and hot, sulfurous shafts. Floods proved the most frequent, and vexing, problem. Yet all that was required was some way to pump out water. After a particularly disastrous flood swamped one mine, stopping production, Ralston, with typical energy and optimism, installed a so-horsepower pump—the biggest yet created. But the pump proved so ineffective against the rising lake inside the mines that within eight months the water engulfed the outmatched machine. It was typical, however, of Ralston to order the Vulcan Foundry, which he helped support with his investments, to construct a 120-horsepower pump.

While Ralston struggled with the water problem in the mines, he grew concerned that his bank had made far too many—and too generous—loans. In the process, though, the bank had helped to start woolen mills, a sugar refinery, an insurance company, a railroad equipment manufacturing company, a winery, lumber mills, gas and water companies, and the Sacramento Valley Railroad, as well as invested in other existing projects, such as the Vulcan Foundry. In these early days, banks not only loaned to businesses but also owned substantial portions of a number of enterprises. Of course, with each new investment, Ralston either became an official or de facto member of the board, or the manager of the business. Ultimately, so many businesses owed at least some part of their existence to Ralston's Bank of California that Ralston biographer George Lyman called him the "Atlas of the Pacific," for upon his shoulders "rested the financial structure of the Pacific Coast."[42]

By establishing a branch for his bank in Virginia City, Ralston had presented California with a gift for posterity. Branch banking existed in many parts of the world, including the antebellum American South.[43] Other California bankers had established small branches, but the practice was certainly not universal, nor were the benefits and efficiencies of branching well publicized outside the South. But Ralston realized that San Francisco's economy differed somewhat from Virginia City's, and that the more flexibility his bank had to shift resources back and forth, the more likely it could withstand crises, which were sure to come given the vicissitudes of mining. In Ralston's first big gamble with mining investments, it looked as though even the more resilient branch structure might not save him: he received constant pleas from Sharon for more cash, to the tune of more than $650,000, to keep the

Comstock drills going. Silver existed in abundance, Sharon reassured Ralston, and "Atlas" went beyond what traditional bankers would have seen as their obligations in financing all of the mining ventures. Ralston's gamble paid off in 1865, when the Kentuck mine produced silver. Within a year it yielded $2 million of the metal, making the Bank of California flush with more than $1 million in profits.

Ralston plowed much of the profit back into the bank, building the most elaborate financial headquarters west of the Mississippi, with tall arched windows and nineteen-foot-high ceilings capped by ornamental vases. The banks interior sported polished dark wood counters, and though it lacked the traditional tellers' cages, the bank advertised its four massive vaults, each formed of a three-inch-thick wall of stone. Enclosed in green glass were inner offices where Ralston and the cashier worked. Contrary to the layout of most banking houses of the day, there was no "ladies banking room." The bolder sort of women who lived in California deposited their funds with the same dark-suited tellers who served the men. To attract Chinese customers, Ralston employed Chinese tellers, whom he exempted from his dress codes by allowing them to wear dark silk robes and their customary long braids.

Beyond the bank, Ralston's influence ran deep. He built the huge, unrivaled Palace Hotel, and, to internalize the costs of construction, he purchased foundries, furniture businesses, and other supporting enterprises. He lent money to the Japanese government to buy railroad engines from California manufacturers. In 1874, he created a new silver coin, called the "trade dollar," to encourage Asian suppliers to hold money earned in trade.

By August 1875, however, Ralston's overextended empire caught up with him. That year, a nationwide financial panic reached California, sparking runs that closed the Bank of California. The day the bank closed, Ralston, perhaps facing the impending bankruptcy of his personal estate, went for his regular swim in San Francisco Bay. He was observed in a brief struggle but died before he could be brought ashore. The "Atlas of the Pacific" had put down the globe for good, but the bank managed to reopen in October of the same year.

Prior to his demise, however, Ralston also demonstrated another characteristic of early California banking, that of domestic capital investment that eventually became capital export. Far from the claims of some contemporaries and historians that eastern interests used the West as a "colony," the California banking experience suggests just the opposite—California's banks, built by men with little imported capital, prospered to the extent that they reinvested their fortunes in the state's economy. The "Irish Four" of John Mackay, James Fair, James Flood, and William O'Brien, who opened the Bank of Nevada in San Francisco in the early 1870s, had started as saloon owners and miners. Although they all became rich from investments in the Comstock Lode, Flood could not hang onto his money, going broke first in the 1850s and having to work as a carpenter to pay his debts. Flood rebuilt his empire, but again

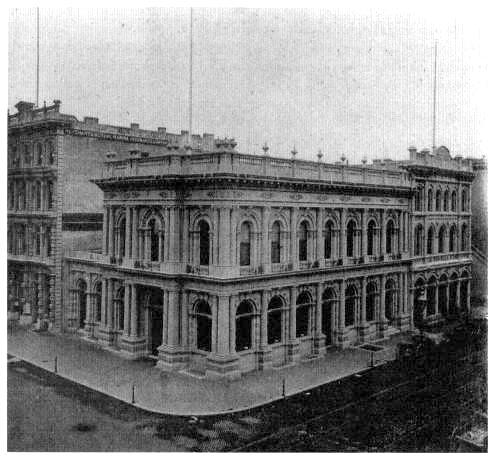

Designed by the Scots Argonaut David Farquharson, the Bank of California was

constructed in 1866 and 1867 of granite quarried on Goat Island in San Francisco

Bay and proved more solid than the fortunes of its founder, William C. Ralston. For

his design of the most powerful banking house in the American West, the architect

drew freely on Jacobo Sansovino's Library of St. Mark, creating an elegant

Renaissance Revival temple of finance. The interior, equally as distinguished as the

faade, was richly finished in black marble and Spanish mahogany. Courtesy Society

of California Pioneers .

lost it all in a wheat speculation with Mackay that cost the partners as much as $12 million. But the mere fact that a pair of California ex-saloon owners could become major investors in the wheat market provides some evidence as to their wealth.

The diminished fortunes of Mackay and Flood after the 1870s paved the way for the arrival in San Francisco of another early California financial legend, Isaias Hell-man, who had come to Los Angeles in 1859 from Bavaria.[44] The dry goods store he started featured a Tilden & McFarland safe, allowing him to diversify into banking activities as early as 1865. His was not the first incorporated bank in Los Angeles, an

honor that belonged to James A. Hayward and John G. Downey, who started their bank in 1868. But Hellman quickly developed a reputation as one of the most solid businessmen in the region, and in 1871 he merged his bank with Downey's, bringing in twenty-three other local business and agricultural leaders to form the Farmers & Merchants Bank of Los Angeles. In 1876, Hellman replaced Downey as president after a panic nearly closed the institution. The Farmers & Merchants Bank prospered, and Hellman's business interests extended throughout the state. When in 1891 directors were looking for a new president to take over San Francisco's Nevada National Bank, which the Mackay-Flood losses had weakened, Hellman left Los Angeles to accept the position. He led the banks return to prominence and its merger with Wells Fargo Bank and Union Trust Company. Like his contemporaries, Hellman invested heavily in California, organizing railroads and becoming a local philanthropist.

In many ways, the ascension of Hellman and the passing of Ralston and the Irish Four marked the end of the frontier period in California's banking history, essentially closing the frenzy begun with the Gold Rush. The early merchant-banker, who relied on safes, vaults, personal reputation, and customer loyalty to maintain business, gave way to a new, professional class of managers. In addition, the regulation of banks—while still largely in the hands of the bankers themselves—came to be viewed as a public policy issue, at least to some degree.

The 1860s and 1870s brought depression and disruption to the California economy. Completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869 had caused unemployed railroad workers to descend on the cities. Speculation increased land prices dramatically, and droughts in southern California thinned the cattle herds. Ranchers who had borrowed against their land to expand when gold and silver had made the state prosperous found themselves overextended and often lost their land to lenders.[45] Sympathy for the economically distressed, combined with the traditional antibanking sentiment, led legislators to further regulate banks. The resulting state Banking Act of 1878 created a Board of Bank Commissioners and required all banks to pay a license fee, to file reports, and to submit to examinations twice a year. Only Indiana, Iowa, and four New England states preceded California in requiring examinations.[46]

Civil War measures by the Union government had also centralized and nationalized control over American banking far more than ever before. After 1864, notes issued by private, state-chartered banks were taxed nearly out of existence. Money from the newly created national banks circulated, replacing private and state banknotes. While still only connected in the loosest of associations through the federal government and supervised liberally by the Comptroller of the Currency, the national banks nevertheless indicated a new attitude toward bank regulation. With the new national charters, however, came increased examination and supervision by the federal government. A national banker could not merely publish the balance sheets

or income statements, but rather had to submit to routine inspections, after which the government examiner would declare the bank "safe and sound" (assuming, of course, that it passed). When California began examining the state-chartered banks in 1878, of the first five banks examined, examiners closed the first and passed the second. The next three closed before the inspectors arrived.[47]

The growing but gradual changes in the supervision of banks by state and federal agencies often are viewed by historians as reforms resulting from public outcry. In reality, increased regulation often shifted the public's perceptions of a bank's stability from visual and material symbols, such as the building or the banker's personal wealth, to more "professional" and "expert" endorsements that perhaps in the long run were of far less value. Involvement by the federal government, through the national banking system, also began the relentless transfer of local control over financial institutions to the central government.

Control demanded that as many banks as possible be brought into the national bank system, and federal authorities assumed that the privilege of issuing national banknotes—and the corollary taxing of private or state banknotes—would do the trick. California banks, however, had developed a much different commercial emphasis than had many state banks in other regions, where the issuing of notes constituted a major element of the institution's business. In California, with its abundance of gold, the banks had concentrated on loans and investments, not note-issue, and therefore when the national banking system was established, its most valuable prize for a bank joining the system—the authority to issue tax-free and easily recognized national banknotes—enticed very few California banks to join.

Californians demanded coin in almost all daily transactions, and few trusted the Union government's supplemental Civil War paper currency, known as "greenbacks" (which, unlike national banknotes, were issued directly by the government). When the California Supreme Court upheld a law allowing contracts to specify the type of money acceptable in payment, it essentially defied the U.S. government's contention that greenbacks were "legal tender."[48] Most lenders demanded gold in payment, leaving the U.S. customs collectors as almost the only people in the state willing to accept greenbacks. Congress realized that as long as gold circulated as freely as it did, the national banking system could not make any inroads in California. Accordingly, in 1870, Congress amended the National Bank Act to provide for the creation of national gold banks, with new notes payable in gold coin. Congress required that the banks hold a 25-percent reserve in specie—substantially higher than most antebellum private banks would have held—and limited the total amount of outstanding gold notes to $45 million.[49] Ten gold banks were organized in California, and when all national banknotes became redeemable in specie in 1879, all ten switched to standard national charters.[50]

Even though the "gold" period in California's banking history did not end until

the demise of the gold banks, the gold-rush era had closed with the end of the Civil War, if not sooner. California banks passed from the frontier stage, characterized by individual responsibility for bank solvency and safety, to the managerial stage, in which trained professionals directed the activities of the banks under the oversight of state, then later state and federal, authorities. Yet the conditions that had given birth to Ralston, Hellman, the Irish Four, and D. O. Mills still shaped the state's financial institutions. Branch banking was tailor-made for a state as large as California, with its diverse economy.

By the end of the frontier era in California's banking history, several enduring features had been established. First, despite Americans' traditional suspicions of banks, the mere presence of banks from the earliest times led Californians to a certain comfort level with the institutions. Despite concerns by legislators, and in the twentieth century attacks by radical groups or "public interest" spokesmen, most Californians accepted banking as a necessary and useful part of daily economic life. Except for the early constitutional debates, banks generally escaped the harsh criticism or outright ostracism frequented on institutions in Wisconsin, Arkansas, Mississippi, or Iowa, where at various times the practice of banking or the establishment of a bank was prohibited by law or all but eliminated. That acceptance, in turn, meant that Californians—from farmers to millers to shippers to innkeepers—did not hesitate to seek new capital to expand agriculture, commerce, trade, and industry.

Second, the symbols of safety worked as planned, suggesting that consumers were more capable of judging the vitality of their financial institutions than many advocates of regulation have thought. Certainly, many of the early banks eventually failed. But that neither dissuaded consumers from using banks, nor other entrepreneurs from starting new ones. Moreover, of those banks that failed, few collapsed because of the actions of a villain who profited at public expense. In almost all cases, the founder or owner sacrificed everything to keep the institution alive and to meet obligations, even to the point that individual fortunes were exhausted for the sake of the bank.

That point underscores a third characteristic of early California banking, which was the persistent use of coin as currency. While popular for a time, the use of gold dust in daily transactions proved neither practical nor desirable, and coin, and soon paper money, quickly found their way into circulation. Paper money, however, had to be redeemable in gold. Californians hesitated to accept greenbacks, not because they were paper money, but because they were unbacked paper money from the government. Evidence from other sections of the country suggests that the "free bank" era of private note-issue was a success, and a substantially revised interpretation of that period, which has been emerging for over a decade, now appears to be the accepted position among economic historians. Far from demonstrating that paper money, and privately created paper money at that, would not work, experience in California showed that consumers will select a variety of exchange mechanisms as

these suit their needs, and that the least desirable of all money was that issued by the government as "legal tender."

Finally, California's adoption of branch banking, while not prevalent in the early frontier era, proved a critical step in the long-term economic vitality of the state. It was the perfect system for a large, economically diverse state (while, in contrast, branching proved less effective in states with more homogenous economies, such as Nevada or South Carolina in the 1920s).[51] The state, sometimes through deliberate action, occasionally by accident, developed a thriving, diverse, flexible banking structure that by the 1980s saw the temporary ascension of a California bank, Bank of America, as the largest bank in the world. That bank was then only one of many large competitors in the state, suggesting that the attitudes and structures generated by, and during, the Gold Rush proved exceptionally durable and flexible over the subsequent century and a half.