Chapter V—

The Extent of Disentail

It is relatively easy to follow the legislation on disentail in these years. The decrees, cédulas, and circulars can be found in various collections in the Archivo Histórico Nacional in Madrid. It proved much more difficult to study the sales themselves and the other transactions that resulted from the legislation. I was unable to locate the records of the Amortization Fund and Consolidation Fund (Caja de Amortización and Caja de Consolidación).[1] At the local level, the provincial historical archives are assembling the past records of the notaries. The volumes from these years contain copies of the original notarized deeds of sale of the disentailed properties. Here one can find samples of the sales, like the one described in the first pages of this book, but it is impossible to study the process throughout the monarchy, because many volumes of notarial records have been lost. Even if they had not been, the task would be forbidding. The deeds of sale are bound along with the other notarized documents of the time and can be located only by a search through the entire notarial collections for these years. Each deed of sale is lengthy, at times having as many as fifty folios. Anyone who has worked with notarial archives is aware of how long it takes to review them for one province, let alone fifty. Another possible source is the records of the former

[1] Some of the records of the Caja de Consolidación are in the archive of the Dirección General del Tesoro, Deuda Pública y Clases Pasivas, in Alcalá de Henares (see Cuartas Rivero, "Documentos"). When I checked with this archive in the 1960s, its catalogue did not yet list these records (except for a volume of 1824), and I have not used them.

contadurías de hipotecas (property record offices), which are also being collected in the provincial historical archives. Carlos III founded these offices in 1768 in the cabezas de partido to record liens and exchanges of property.[2] The instructions on desamortización of January 1799 ordered the contadurías de hipotecas to record the sales.[3] It is easier to follow the transactions here than in the notarial documents, because the offices recorded the essential details in brief, and they contain very few other entries in these years. They are, in fact, one of the basic sources for the study of disentail in individual towns in Part 2 of this book. Nevertheless, in the provincial historical archives of Jaén and Salamanca, which I used, a number of registers of the contadurías de hipotecas are missing, and one suspects that the same is the case in other provinces.

Fortunately, I located a source that is relatively complete for the entire monarchy. From the outset the Amortization Fund and later the Consolidation Fund issued notarized acknowledgments or deeds of deposit (escrituras de imposición ) that recognized the royal debt to the former owners of the properties or redeemed censos (the obras pías and other ecclesiastical institutions and the entailed family estates). These deeds of deposit tell us the amount of the royal debt resulting from each transaction as well as other pertinent information and calculate how much the fund would pay the former owner annually in interest. According to the accepted practice, the notary kept a copy of each deed. At first, the deeds of deposit were delivered by provincial notaries, but the funds rapidly centralized the activity in Madrid, using the notary Juan Manuel López Fando and after 1807 Feliciano del Corral. Their records (protocolos ) are now in the Archivo Histórico de Protocolos of Madrid, a total of 147 bound volumes and 17 unbound bundles with 78,428 deeds of deposit dated from 1798 to 1808.[4]

The number of deeds is enough in itself to suggest that Soler's appeal to the avarice of the king's subjects was indeed successful. The deeds consist of printed forms of three pages, recognizing the royal debt to the former owner, with blanks in which to record by hand the details of each deposit. With time, in order to reduce the paper work, the notary's office adopted the practice of including in one deed the proceeds of the sales of various properties when they had belonged to the same institution or estate. Thus there were more sales made than the number of deeds.

[2] Pragmática sanción, 21 Jan. 1768, AHN Hac., libro 8025, no. 2167.

[3] RC, 29 Jan. 1799, AHN, CCR, no. 1240, art. 26.

[4] See Appendix F.

| ||||||||||||||

The amount of the royal debt is recorded prominently at the head of each deed and listed in the index of the volume. It is not usually the same as the sale price. After 16 August 1801, we may recall, when a purchase was paid for in hard currency at less than the assessed value, the crown recognized a debt equal to the assessed value, and for fifteen months it recognized a debt 25 percent above the price received for sales made above the assessed value in hard currency.[5] On the other hand, the legislation required that all censos and other liens on the properties be paid off out of the sale price before the proceeds were deposited in the funds. In these cases, the deeds of deposit represent lower amounts than the sale price. (In this way, we saw, the disentail served to liquidate a larger number of ancient forms of indebtedness and leave the new owners with properties free of encumbrances.) Since some deeds were for more than was paid and others for less, on balance they furnish a first approximation of the value of disentail under Carlos IV. It would require a careful reading of all the deeds to determine the sale price and type of currency used in each case.

Several collaborators carefully totaled the amounts of royal debt listed in the indexes to the volumes, with the results shown in Table 5.1. The difficulty of the task and the state of some of the records means that these totals are not absolutely accurate.[6] Fortunately, there is available a global statement of the deposits in the two funds. When Napoleon forced Fernando VII to renounce the crown of Spain in his favor at Bayonne in May 1808, he commissioned Spanish officials to furnish him

[5] See above, Chapter 4, section 2.

[6] See Appendix F for the method used.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

with detailed information on the finances of Spain. These reports, made from the best information available in Madrid, are now in the Archives Nationales in Paris. Among them are reports on the receipts of the Amortization and Consolidation Funds. They record total deposits, shown in Table 5.2, but do not specify the sources of the deposits.

The total reported to Napoleon for the two funds is 1,653 million, well above the 1,238 million covered by the Madrid deeds studied. To proceed with an analysis of the extent of the disentail of Carlos IV, it is important to know if the difference between the two figures represents missing deeds of deposit or if other moneys are also involved in the figures given Napoleon, such as proceeds from the different taxes assigned to the funds. A detailed analysis of the question, which I have described elsewhere, concludes that the deposits at 3 percent in the Amortization Fund and all those in the Consolidation Fund reported to Napoleon were obligations incurred for sales of disentailed properties and redemptions of censos carried out under various decrees of Carlos IV.[7]

[7] Herr, "Hacia el derrumbe del Antiguo Régimen," 59–65. On the basis of Yun Casalilla, "Venta de los bienes," Appendix 1, which appeared after my article, the table on p. 65 of my article of the amounts of desamortización carried out under the Consolidation Fund should include an additional 4.6 million reales for sales of former Jesuit properties, ordered by one of the decrees of September 1798. No one has yet studied the disposition of the properties of the colegios mayores, which should also appear in this table.

The total of the two is 1,632.8 million reales. The difference between this figure and the total of the Madrid deeds studied is made up by deeds issued in the early years by provincial notaries and late sales for which the Madrid notaries, who fell months behind in their task, had not issued deeds before the end of 1807, the cutoff date of my investigation.

2

Knowing the correct amount collected from the sales tells us nothing about their location. To determine this essential piece of information, we resorted to the deeds of deposit recorded by López Fando and Corral that we have studied. In most instances my collaborators and I were able to establish the location of the properties covered by them. They represent about 80 percent of all the sales, and the total deposits for each province can be projected from them. These provincial totals can then be broken down into the part owed to ecclesiastical foundations and the part owed to lay entails. Table 5.3, Columns A and C, shows the results.[8]

These sums include both money received by the crown for the sale of real properties and money received as redemption of censos. The indexes of the notarial volumes of López Fando and Corral do not distinguish between the two, and it was impractical to review all the deeds to identify the redeemed censos. From a detailed review of the deeds of Salamanca and Jaén provinces, which forms the basis of Part 3 of this study, I estimate that 4.5 percent of the total ecclesiastical deposits came from redeemed censos. By deducting this proportion from the total of each province, Column B of the table gives the estimated provincial totals of deposits resulting from the sale of ecclesiastical properties.

This correction is not applied to Catalonia, however, because a tally of more than half the deeds of this province showed that 61.5 percent of them represented redeemed censos. One can suggest that the reason why there were more redeemed censos in Catalonia than sales of ecclesiastical property is that the redeemed censos included emphyteutic quitrents (cánones emnfitéuticos), which existed widely in that province.[9] If this is the case, the disentail of Carlos IV enabled a number of permanent tenants in Catalonia to establish full ownership of their properties by paying off the capitalized value of their emphyteutic leases with de-

[8] A number of unknowns are involved in calculating this table. The method is described in detail in Herr, "Hacia el derrumbe del Antiguo Régimen," 66–71. The figures in Table 5.3 differ slightly from those in Table 1 of this article due to later corrections.

[9] See above, Chapter 4, section 2.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

preciated vales reales. More research is needed, however, to clarify the effect of this disentail on Catalonia.

A review of the deposits credited to family entails showed that they too include a large number of redeemed censos. The owners of mayorazgos and other secular entails were not required to sell their lands, but they did have to accept the capital of a censo in vales and, after April 1801, to deposit the capital received in the redemption of censos with the Consolidation Fund.[10] This rule may explain the high proportion of redeemed censos among the deeds of deposit in favor of secular entails. A sample of the deeds, drawn from all years and all provinces except Zamora, shows that roughly one-third of the amount deposited in favor of secular entails came from redeemed censos. After making this deduction from the total deposits, Column D of the table gives the estimated provincial totals for deposits from disentailed secular properties.

3

The estimated provincial totals for deposits resulting from the disentail of real property shown in Table 5.3, Columns B and D, have little significance as they stand. They must be transformed into some economically meaningful statistic before one can assess the extent of Carlos IV's desamortización. One would like to know what portion of the property of the church was sold and what portion of all the cultivated land in Spain changed hands. One might base such a proportion on various measures: the area the assessed value, or the value of the annual production. Given the information available, the only practical proportion is the last, because this corresponds to the information provided by the catastro of the Marqués de la Ensenada. The makers of the catastro calculated the value of rural properties according to the average annual sale price of their harvests or their product as pastures. Thanks to the work of Antonio Matilla Tascón, we have available the totals of the catastro for property in the twenty-two provinces of Castile.[11] We lack such information for other parts of the monarchy, which are not covered by the catastro.

Even with the information on Castile it is not possible to compare directly the provincial totals of the catastro with the provincial totals of the deeds of deposit. One must first know the relation between the cadastral value of an average property and the amount of the deed of de-

[10] RC, 17 Apr. 1801, AHN, Hac., libro 8053, no. 6168.

[11] Matilla, Única contribución, Appendixes 10 to 30 and 39b.

posit given for it. Such a relationship can be calculated in some cases. Using the notarized deeds of sale, the registers of the property record offices (contadurías de hipotecas), and the individual town surveys of the catastro (libros maestros de eclesiásticos ) for the seven towns studied for Part 2, I found 139 sales in which I could match the properties sold with properties described in the catastro. I could then calculate the relation between the sale price and the cadastral value of these properties.

It became apparent that different types of property (arable, pastures, olive groves, etc.) produced different ratios of sale price to cadastral value. Arable showed the least markup, with olive groves, urban properties, and meadows each higher in that order. The markup also varied with the different ways in which payment was made. Sales paid for in hard currency had a lower ratio of sale price to cadastral value than those paid for in depreciated vales reales. Similarly, there was a different ratio in cases where a purchase was paid for in hard currency but the royal fund raised the amount of the deed of deposit, according to the cédula of 16 August 1801, to compensate the former owner for not receiving as many reales as he would have if the buyer had bid in vales.[12]

The detailed procedure for these calculations is described in Appendix E. The results show that the real estate of the church brought a good price. Buyers were prepared to pay in hard currency 19 times the cadastral value for arable fields and 34 times for olive groves (for payments in vales reales the ratios were 24 : 1 and 44 : 1). According to the tables of Earl Hamilton, the grain prices in Old and New Castile and Andalusia for 1791–95 averaged 1.78 times those for 1746–55, and for 1796–1800 2.05 times the price of the earlier period, during which the catastro was drawn up. Olive oil prices in New Castile (the only region for which he provides these data) were up 2.06 times by 1791–95 and 2.53 times by 1796–1800.[13] On the assumption that grain and olive production had not risen on individual properties, we can conclude that buyers were willing to pay for grain fields roughly 9.3 times the value of their annual harvests after the beginning of the war with Britain in 1796, and for olive groves 13.4 times, all calculated in hard currency. One can imagine that contemporaries considered the wartime inflation a temporary phenomenon and, if so, based their bids on their recollection of prewar prices in the years 1791–95. In this case they were paying 10.7 times the value of harvests for grain fields and 16.5 times for olive groves. (When bidding in vales, they of course paid more on average.)

[12] RC, 16 Aug. 1801, AHN, Hac., libro 8053, no. 6226.

[13] Grain prices, Hamilton, War and Prices, 183, Table 12; oil prices, ibid; Appendix 1 (prices for 1747 and 1751 missing).

In other words, the buyers were expecting arable fields to produce annual grain harvests worth about 9 to 11 percent of their purchase price, and olive harvests about 6 to 7.5 percent. When we study various towns in Part 2, we shall see that rents for grain fields in Salamanca were between 20 and 31 percent of the harvest, in Jaén about 25 percent on both grain fields and olive groves. Buyers of arable fields who planned to rent them to peasants thus expected a net return of about 2.5 percent on their capital, those of olive groves about 1.5 to 2 percent. These rates were well below what they could get for royal notes, which were shaky, and also below the standard 3 percent for censos, which were guaranteed by the possibility of foreclosure. Since the expectation of continued inflation with which we live in the second half of the twentieth century was not yet present in 1800, the buyers did not discount it. The properties of obras pías clearly brought good prices, despite the haste with which the crown placed them on the market. Jovellanos and the other royal advisers had been correct in assessing a great thirst for land among the holders of free capital in Spain.

4

It is now possible to estimate the extent of the disentail in the provinces of Castile. We know from the catastro of la Ensenada the value of properties belonging to ecclesiastical institutions in each province of Castile. This figure appears in Table 5.4, Column A. Table 5.3, Column B, gives us an approximate total amount of the deeds of deposit for ecclesiastical disentail in each province, but for our purpose it must be converted to an equivalent figure in cadastral value. From Appendix E, we have an estimate of the ratio of the face value of the deeds of deposit to cadastral value for the different forms of payment and the different types of property. We must first establish the proportion of the sales paid for under each form of payment (hard currency, vales reales, etc.). For this purpose, the data on the provinces of Jaén and Salamanca is used as representative of all Spain, admittedly a limited and selective sample but the only one available to me.

Next, we must establish the proportion of the sales made up by each of the different types of property, since the ratio of sale price to cadastral value differed among them. Again we start with the information from Salamanca and Jaén, but it would be unreasonable to expect these two provinces to be representative of the distribution of different cultivations throughout Spain. If we assume that the disentailed properties were a cross section of all agricultural property in each province, we can make

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

the necessary adjustment for each province by using a contemporary source, the Censo de frutos y manufacturas de España é Islas Adyacentes, prepared in 1799 by the royal government.[14] Its information has been shown to be wrong in specific respects,[15] but it can serve to establish a rough concept of the provincial structures of agrarian property, for it gives the value of the different agricultural products in each province.

From Appendix E we learn that in most provinces one can estimate that the mean face value of a deed of deposit was approximately thirty times the cadastral value of the same piece of property (a ratio of 30 : 1). In provinces where the proportion of improved land was high, the ratio would have been higher than 30 : 1 because we found that buyers in the disentail offered a higher markup over the cadastral value for improved land than for arable. These provinces, according to the Censo de frutos, were Córdoba, Galicia, Granada, Murcia, and Seville. The proper ratio appears to be 36 : 1 for Granada and 34 : 1 for the other four. Madrid also needs a special ratio because a large amount of urban property was sold here, at a high markup. A ratio of 43 : 1 is applied. We can now divide the total amount of the deeds of deposit for ecclesiastical disentail in each province (Table 5.3, Column B) by 30 (or the larger number for the six provinces noted) to obtain the approximate cadastral value of the property disentailed (Table 5.4, Column B). With this information, we can calculate a preliminary estimate of the percentage disentailed in each province (Table 5.4, Column C).

Except for Madrid, the percentages in Column C vary between 5 and 28. The figure 50 percent for Madrid is not correct. If the buyer of a property did not live in the province where it was located, he could opt to make his payment to the commissioner in his province. The records show that many residents of Madrid adopted this option, buying properties of considerable value in other provinces and having the sales recorded in Madrid. As a result the Madrid total represents more than the amount sold in its province. Let us suppose that 25 percent of the ecclesiastical properties of Madrid were sold, a credible figure since there were many sales. We must distribute the remainder of the amount deposited in Madrid among the other provinces.[16] The distribution can be made proportional to the amount sold in each province, but the three bordering provinces, Guadalajara, Toledo, and Segovia, deserve more. I

[14] Censo de frutos y manufacturas.

[15] Fontana Lázaro, " 'Censo de frutos y manufacturas.' "

[16] We must use the ratio 30 : 1, not 43 : 1 of Madrid. The provinces of Castile represent 79 percent of all the sales outside Madrid; we must distribute only this much of the remainder among them.

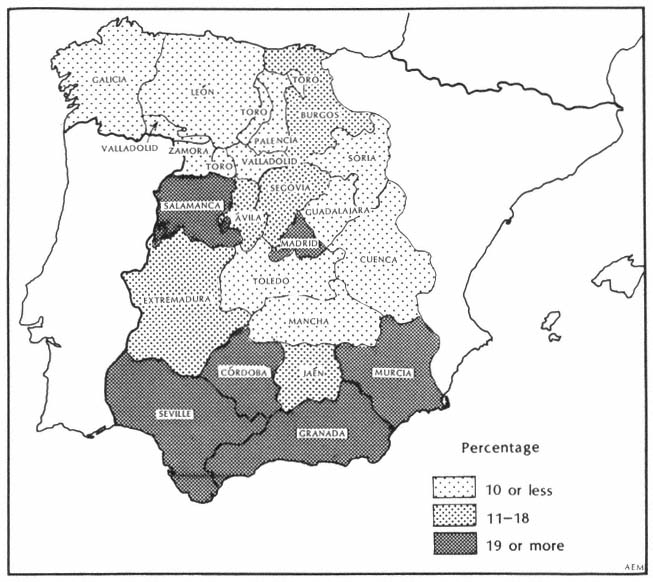

Map 5.1.

Castile, Proportion of Ecclesiastical Property Disentailed, 1798–1808

have assigned them a proportion double that of the other provinces. The result is that one must increase the amount of sales in provinces outside Madrid by 8.06 percent and in Guadalajara, Toledo, and Segovia by 16.12 percent. Raising Table 5.4, Column B, by these percentages, one obtains the results in Column D. The corrected percentages of ecclesiastical property disentailed are in Column E. They run from 6 to 30 percent.[17]

The significance of this table can be better understood by looking at the results in Map 5.1. It becomes clear that the disentail had more effect in the south than elsewhere. There is an impressive block of provinces from Seville to Murcia where 19 percent or more of the properties owned or controlled by the church were sold, and in Jaén the propor-

[17] There have been some recent studies of the desamortización of Carlos IV, but they do not provide provincial totals that can be checked against Tables 5.3 and 5.4: Campoy, Política fiscal; Marcos Martín, "Desamortización"; and Pardo Tomás, "Desamortización."

tion was 16 percent. Other areas of high sales were Salamanca (20 percent) and Madrid (25 percent, although the figure for Madrid is arbitrary, as we saw). At the other extreme are two blocks of provinces where 10 percent or less was sold: the northwest sector of the kingdoms of León and Old Castile, including Galicia, and all New Castile except Madrid and Extremadura, together with Soria, which borders on this block to the north. Between these two blocks runs a belt of provinces from Burgos to Extremadura, including Segovia and Ávila, where between 14 and 17 percent was sold. Because of the number of unknowns in our calculations, one cannot expect the percentages to be exact, but the pattern revealed by the map is hardly likely to be the result of a coincidence of errors.

Probably the most important factor in accounting for the pattern is the proportion of ecclesiastical property that belonged to obras pías, memorias, and other foundations subject to the decree of 1798. It was very likely greater in the areas of higher disentail, but there is no easy way to check this assumption. Human factors also played a part, for much depended on the dedication and efficiency of the royal commissioners in charge of the operation. On the other hand, factors such as regional types of agriculture or local weather did not have much effect. An analysis of the total value of sales in each province in each year produces no regional patterns, as one would expect if the kind or size of harvests had played a role. A large proportion of sales in one province might occur in a year during which there was little activity in neighboring provinces. (There was, however, a decline in sales in most provinces in 1803, 1804, and 1805, years of bad harvests and rural crisis.)[18]

The dedication of the local commissioners was critical, as the royal advisers were aware. Repeatedly in the early years, the king issued circulars to the intendants urging them to put pressure on their subordinates and local justicias to hasten the sales.[19] The archives of the ministry of hacienda include a copy of an order dated November 1799 from the intendant of Seville to the justicias of the province to push the disentail, threatening, if they did not, to send a royal agent at their expense to act for them.[20] In 1804, when sales were notably slow, the king through the president of the Consolidation Fund once more pressed the intendants to use all their energies to hasten the affair. Again the intendant of Seville passed the word on to the justicias of his province, with the warn-

[18] For the annual sales for all Spain, see Appendix F.

[19] Circulares, 18 Nov. 1799, 26 Mar. 1800, 7 May 1800, AHN, Hac., libro 6012.

[20] Circular, 15 Nov. 1799, ibid.

ing, "If as a result of your inactive disposition I do not see all the good effects that ought to be forthcoming, I shall take against you the most serious measure that corresponds to your indolence in a matter so stringently urged by higher authority."[21] Seville was one of the regions where a high percentage of ecclesiastical property was sold, but it is impossible to tell from the evidence here if the intendant's threats overcame the perennial problem of administrative linkage with local officials whose loyalties lay elsewhere or if the province had a greater than average number of eager potential buyers with disposable capital.

A judge of the Cancillería of Granada, who bitterly opposed the disentail, later described in scathing terms the attempts of the government to force its officials to carry out its instructions. All to little avail, the judge recalled: "But despite such efforts the truth triumphed, de jure and de facto, and in accord with it they [the agents of the crown and the prelates of the church] remained remiss in the consummation of the sales, presenting a tacit resistance in this prudent way, in default of open resistance, which they could not and should not oppose to an irresistible force."[22]

As the judge pointed out, the attitude of the church authorities was also a factor. Capellanías and charitable foundations whose properties had been donated by religious institutions could not be sold without their permission.[23] It is easy to imagine that few prelates accepted with alacrity the royal invitation of 1798 to proceed with disentail. One who did was the Jansenist bishop of Salamanca, Antonio Tavira y Almanzán, a friend of Jovellanos,[24] who favored the undertaking. Many properties of capellanías were sold in Salamanca, but few in Jaén.[25] Besides Madrid, Salamanca was the only province outside Andalusia that had more than 19 percent of its church properties sold, Jaén the only province in Andalusia below that figure. The attitude of servants of church and state may explain these peculiarities in provincial responses; nevertheless, the overall pattern observed in Map 5.1 must reflect major regional differences in the nature of ecclesiastical property, that is, conditions produced by previous history.

According to these calculations, 15 percent of all ecclesiastical property in Castile was disentailed. It is true that this proportion is based on

[21] Circular, 5 Nov. 1804, and letter of intendant, 14 Nov. 1804, ibid.

[22] Reguera Valdelomar, Peticiones, 125.

[23] Circular, 18 Nov. 1799, AHN, Hac., libro 6012.

[24] Herr, Eighteenth-Century Revolution, 415–16; Saugnieux, Prélat éclairé, 269–70.

[25] As determined by the study of the towns in Part 2.

the only total figure available for ecclesiastical property derived from the catastro made under Fernando VI, but the holdings of the church would not have increased much by the reign of Carlos IV. This was no longer a time of large grants for religious ends, and the government frowned on any increase in manos muertas. In making these calculations I have been careful not to overestimate the proportion sold, leaning rather in the other direction. Fortunately, there is independent confirmation of its extent. Among the questions that Napoleon posed the Spanish bureaucrats in 1808 were the following: "What is the amount of capital that is the product of the sales of the properties of charitable foundations [obras pías]? Of the clergy? What is the estimate of how much remains to be sold of the properties of charitable foundations and of the clergy, in comparison with the quantity of both kinds of property whose sale has already been ordered?" The Spanish officials did not give an exact answer to the first question because no one had kept a separate tally of disentail of "obras pías" and "clergy." They replied that the sales of obras pías might be 950 million and of the clergy (that is, capellanías) 237 million, a total of 1,187 million. (We know that this figure is low.) To the second question they replied that there remained to be sold 250 million worth of obras pías and 650 million of capellanías. Furthermore, a papal breve of 1806 had approved the sale of one-seventh of all other ecclesiastical property.[26] The officials calculated this seventh to be worth 500 million; that is, they believed the total to be 3,500 million.[27] These figures produce an estimate of the total value of all ecclesiastical property in Spain before the disentail of 1798 of 5,587 million reales. What the Spanish officials estimated had been sold, 1,187 million, was 21 percent of the total.

Thus the financial advisers of Fernando VII believed that a greater proportion of property of the church had been sold than we estimate. They were referring to all Spain, not just Castile; nevertheless, I believe our figure to be closer to the truth, although 15 percent may be too low. One can be reasonably sure that a sixth of all ecclesiastical property was disentailed. In most provinces of Andalusia it was a fifth or more, and, if the figures of the catastro are correct, it was almost a third in Murcia. One must conclude that the disentail of Carlos IV was an event of major significance in the history of the Spanish church and church-state relations.

[26] See below, Chapter 6, section 4.

[27] ANP, AF IV, 1608 , 20 : 26.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

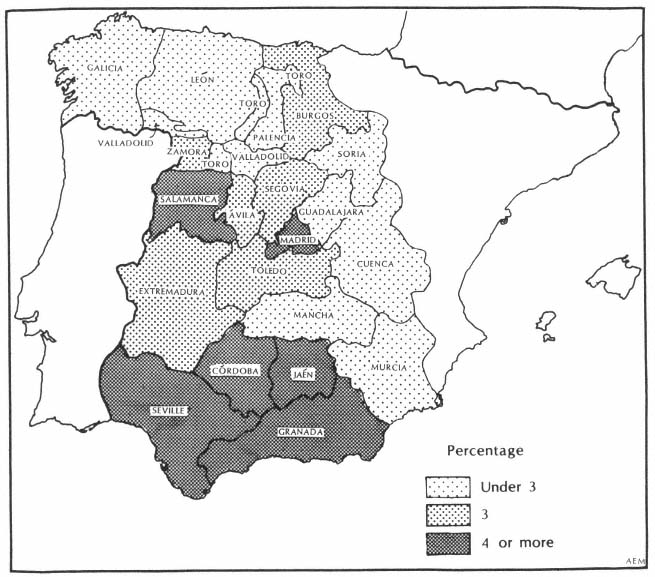

Map 5.2.

Castile, Proportion of All Property Disentailed, 1798–1808

5

Thanks to the catastro it is also possible to calculate the approximate proportion of all the properties in Castile that changed owners in these years as a result of desamortización. The procedure is identical: obtain the total value of the property in each province according to the catastro and compare it with the total of the deeds of deposits (in this case using both ecclesiastical and family entails). To make the comparison, we use the same ratios of deeds of deposit to cadastral value as in Table 5.4. The results are given in Table 5.5 and Map 5.2.

The proportion of all real property that was disentailed in Castile then is estimated to be 3 percent. The highest percentage of land that changed hands was in Andalusia, Salamanca, and Madrid, 4 percent or more. In second rank were Zamora and the belt from Burgos to Extremadura, including this time Toledo, where 3 percent was sold. In other

regions, the northwest of Old Castile and León and the south and east of New Castile, with Soria and Murcia, the figure was below 3 percent.[28] But in Salamanca it reached 7 percent, and in Seville, 6 percent. In the first, approximately one property out of every fourteen—in the towns and the countryside—changed hands, and in the second one out of seventeen, and in the rest of Andalusia one out of twenty or twenty-five. Since these are only provincial averages, there were towns and cities where the transfer was greater, as appears to have been the case in Madrid.

Andalusia and most of the province of Salamanca lay southwest of the Salamanca-Albacete line. The disentail of Carlos IV hit hardest in the region of large properties, the areas that the counselors of Carlos III had singled out as in most need of agricultural reform and that have been marked by great estates to the present day. In due course we shall have to consider whether the desamortización served to improve conditions, as its proponents hoped, or exacerbated an already bad situation, as the critics of desamortización hold.

[28] Although according to our calculations Murcia had the highest proportion of ecclesiastical disentail, the proportion of all property disentailed was low because the province had relatively little ecclesiastical property, according to the catastro. One may question the accuracy of the catastro for Murcia, but there is no easy way to check it.