Two

Self-Theatricalization in Victorian Pictorial Dramaturgy: What's His Name

Melodrama as a Middle-Class Sermon

On July 13, 1914, seven months into his first year as director-general of the Lasky Company, DeMille began to film an adaptation of What's His Name , a minor novel that had not previously won acclaim on the legitimate stage.[1] Since his first three features, The Squaw Man, The Call of the North , and The Virginian , were screen versions of well-known plays that could boast the location shooting, action scenes, and frontiersmen typical of Westerns, What's His Name was a significant departure. A domestic melodrama based on an unconventional sex-role reversal, it represented DeMille's first effort to rewrite a genre that his father, Henry, C. DeMille, had formulated in collaboration with David Belasco in the 1880s and 1890s. To put it another way, melodrama translated from stage to screen as an intertext was in some measure a DeMille family enterprise. According to the tradition of well-made plays crafted by his father and by his brother, William, DeMille resolved the personal and family dilemmas signifying the ethical crises of modern urban life by constructing his mise-en-scène as an instructive tableau. That he was unable to do so with the moral clarity so compelling in late-nineteenth-century stage melodrama reveals a great deal not only about the evolution of the genre but about the transformation of middle-class culture in the early twentieth century.

A discourse on gender, What's His Name registers ambiguity about social change during an era when a broadly defined middle class, differentiated between "old" independent farmers and small businessmen and "new" salaried white-collar workers, was undergoing a transition in its composition, ethos, and life-style. Caught between visible extremes of urban wealth and poverty, middle-class families, with annual incomes ranging from $1,200 to

$5,000, sought to define their social identity in terms of a distinctive style of living.[2] The old ingrained habits of self-denial, restraint, and frugality were giving way to an investment in comfort and refinement as signifiers of genteel status. As What's His Name demonstrates, however, such a practice was fraught with danger because it remapped private versus public spheres based on traditional definitions of gender and vitiated the differentiation between home and marketplace.[3]

What's His Name takes place in Blakeville, a small town whose inhabitants engage in simple pleasures such as enjoying refreshments at a soda fountain, but not so small that it is unexposed to touring companies that travel by rail and provide the lure of big city attractions. At the beginning of the narrative, Harvey, unidentified by a surname and destined to become "What's His Name," marries his sweetheart Nellie against the objections of Uncle Peter, a crusty bachelor who resists the tyranny of domestication. DeMille moves his camera in for a medium shot at the wedding as Harvey plunges out of a crowd of guests to search frantically for the ring, a nervous gesture that betrays his uneasiness. An intertitle, "Three Years Later," marks the passage of time. Nellie has become disenchanted with housewifery and mothering a young daughter named Phoebe. Attracted by a musical comedy troupe performing in town, she responds eagerly to an opportunity to join the chorus at a salary of twenty dollars a week. A sign of his diminished status in the role of maternal substitute and lackey, Harvey is carrying Phoebe as well as luggage at the train station when the family departs for New York.

After an auspicious debut, Nellie becomes the "Toast of Broadway" and attracts the attention of a millionaire named Fairfax, who typifies the silk-hatted, paunchy villain signifying greed in Progressive Era cartoons.[4] A scenario representing the moral dilemma of a consumer culture, What's His Name shows a small-town comedienne neglecting her family and succumbing to the lure of upper-class finery. But the morality of self-denial personified by Uncle Peter and characteristic of the propertied "old" middle class ultimately prevails. When her child becomes seriously ill, Nellie relinquishes the excitement of theatrical life and resumes her duties as a wife and mother. As discourse on women and the family, the film thus reconstructs traditional gender roles but not without the ambiguity rendered by lighting effects in the final tableau. A close analysis of this melodrama is intriguing, but it first requires contextualization with respect to the role of women in the formation and social reproduction of the middle-class family; their control over social and theatergoing rituals as these defined the self in relation to others in genteel society is especially relevant for an informed reading.

As historians and sociologists point out, the access of the middle class to education meant that particularly the upper level of this socioeconomic group, albeit subject to the homogenizing forces of the leisure industry, would nevertheless exercise cultural power disproportionate to political

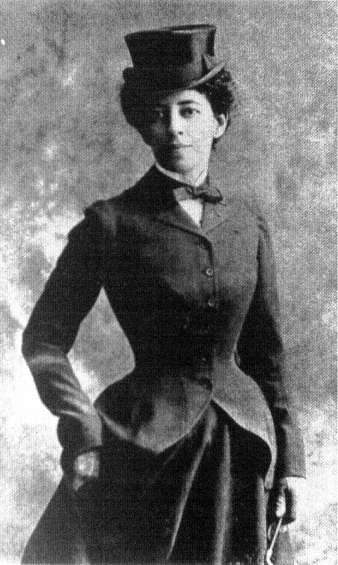

8 and 9. Cecil B. DeMille's parents: playwright Henry

Churchill DeMille, and (opposite) theatrical agent Matilda Beatrice

Samuel DeMille. (Photos courtesy Brigham Young University)

power. The genteel middle class in fact wielded enormous influence through its redefinition of womanhood and the family. As established by the practice of native-born, Protestant households, the privatized family became a refuge from the marketplace, especially in suburban communities built away from downtown business districts after the Civil War. Particularly essential in middle-class formation, as Mary P. Ryan argues, was the role of women who supplemented family income by taking in boarders, shopped with great economy, and saved enough money to educate sons. Given a

pattern of financial investment in the education of sons, matrilineal ties persisted in the lives of young men.[5] A case in point is DeMille's own family. When his mother became a widow with three children in 1893, she resolutely provided for the future. A resourceful woman, Beatrice DeMille founded the Henry C. DeMille School for Girls at the Pompton, New Jersey, estate that

her husband had purchased two years before his untimely death. She also capitalized on the rights to the celebrated DeMille-Belasco plays to establish herself as a theatrical agent for playwrights. Although she never learned to manage finances and heavily mortgaged the family estate, she made certain William was educated at Columbia University and Cecil at the Pennsylvania Military College. When her younger son decided to gamble on filmmaking in 1913, she sold her theatrical agency for twenty-five thousand dollars to provide him with the requisite capital.[6] Years later, he confided to an interviewer, "we have to bring out the tremendous personality that she was and how much I am 'operating' from her, because it's an awful lot."[7]

Women demonstrated resourcefulness in transforming the middle-class family under their own supervision because men were no longer heads of "corporate and patriarchal households" characteristic of an agrarian era.[8] A feminization of American culture thus occurred under the leadership of women allied with clergymen because both, lacking traditional access to power, elevated passivity to a virtue in sentimental discourse. The pervasiveness of sentimentalism in genteel circles understandably provoked a surge of the martial ideal in definitions of masculine selfhood and in pursuit of American foreign policy at the turn of the century. According to T. J. Jackson Lears, middle- and upper-class men who felt suffocated by over-civilization, luxury, and effeminacy endorsed the strenuous life exemplified by Theodore Roosevelt in his frontier, hunting, and military exploits. Distinctions between manual and nonmanual labor as an index of class and ethnicity, in other words, meant that privileged men would ritualize the pursuit of athleticism. After the Census Bureau declared the frontier closed in 1890, for example, the Westerner became a compelling figure in such best-sellers as The Virginian (1902), dedicated to Theodore Roosevelt by a Harvard classmate.[9] DeMille's first three adaptations, including The Virginian , also exemplify the revitalization of men as frontier heroes in Westerns. A domestic melodrama, What's His Name affirms to the contrary that male bravado expressed barely submerged fears of castration. Such a contrast in discursive modes reveals fault lines based on gender within the privileged social strata. To put it another way, sentimentalism with its polite evasiveness about urban conflict, on the one hand, and masculine quest for potency with its emphasis on self-realization, on the other, were expressions of sexual conflict in an age when class hegemony remained intact. As manifestations of Victorian homosocial or sex-segregated culture, however, both sentimentalism and embattled masculinity served to accommodate the growth of consumer capitalism because the rhetoric of spiritual uplift was co-opted to rationalize self-fulfillment.[10]

The influence of genteel women in establishing middle-class culture as a matrix that governed the formation of the self in relation to a consumer

10. Correspondence addressed to DeMille by his mother, Beatrice, who

continued to manage his finances after he became director-general of the

Lasky Company. (Photo courtesy Brigham Young University)

society cannot be underestimated. Particularly relevant were theatrical modes of self-representation in polite forms of social intercourse and in elaborate parlor games that anticipated the reemergence of the elite in fashionable theaters. The publication of numerous etiquette manuals implied that an entrée into society was possible, but rituals such as the "ordeal by fork" at dinner parties required elegant comportment and dress, thus winnowing the field. As families with disposable income began to spend increasingly on comfort and refinement, social practices like ceremonial callings in genteel parlors became preludes to concourse in ostentatious public settings such as theaters, department stores, and museums.[11] A sign of private and public spheres intersecting in the art of self-theatricalization, middle-class women learned how to gesture and pose according to the Delsarte system of acting. A notable foreign import, this French schematic expression of human behavior was introduced in the 1870s by Broadway producer Steele MacKaye at the Lyceum Academy, subsequently renamed the American Academy of Dramatic Arts by Henry C. DeMille.[12]

Anticipating the revival of theater attendance among the upper middle class, dramaturgical modes of self-representation and social interaction flourished in the form of mid-nineteenth-century parlor games and theatricals. As Karen Halttunen has documented, upper-middle-class society engaged in performances of charades, proverbs, burlesques, farces, tableaux vivants, and shadow pantomimes that were quite elaborate in the use of costumes, sets, lighting, sound, and special effects. What accounts for this fascination with artifice in an industrial and urban setting? Why was playacting so integral to middle-class culture, especially in an era of increased consumption? According to Halttunen, the urban environment represented a "world of strangers" that endangered social relations and thus required adherence to a semiotics of performance rituals ensuring gentility. Social intercourse in this guise resembled a charade, however, in which actors engaging in self-theatricalization signified the decline of character based on moral virtue and the rise of personality associated with consumption. Consequently, the private theatrical represented a play-within-a-play because the parlor had become a stage for observances in which proper attire and decorum were but aspects of a performance. Yet these communicative acts, as Erving Goffman argues, were nevertheless morally implicated because they raised questions about the nature of "claims" and "promises" being transmitted.[13] The social transactions of a consumer culture thus resulted in ethical dilemmas such as those involved in performance rituals that the genteel classes by no means succeeded in resolving.

Undeniably, upper-middle-class society was being transformed in drawing room pursuits that placed a premium on self-commodification, a problematic basis for a personal sense of identity as well as for social interaction. Genteel women thus presided over rituals that eroded a legacy of evangelical

Protestantism expressed as moral empowerment in sentimental discourse. But if cultivated women stepped off their pedestals, they succeeded in dictating the terms of access to respectable society and thereby extended their influence into the public sphere. All the world became a stage as the middle class began to engage in ritualistic theatergoing after having earlier abandoned the scene to the boisterous lower orders in the gallery. While congregating in lavish foyers or enjoying a performance on stage, formally attired audiences engaged in a form of playacting scripted according to social conventions. Across the country, a building craze responded to middle-class demand for grandiose theaters as a setting for self-display and social intercourse. The Providence Opera House, for example, was built in record time with a budget exceeding expenditure on all the city's previous theaters combined. Unveiled in 1871, the magnificent new structure showcased a melodrama titled Fashion, or Life in New York because "it gave the ladies an opportunity to show some handsome dresses." Similarly, Pittsburgh's aspiring middle class demanded a "New York" theater without galleries that seated the lower classes to accommodate syndicated shows in the 1890s.[14]

The construction of ornate theaters of" Moorish and rococo designs" not only represented a shift in patterns of genteel middle-class consumption but signified a decline in the Victorian practice of separate spheres for the sexes. As a social agency, the theater became the site of transition between the privatized home and the marketplace as these two institutions began to converge. An important aspect of this transformation in theatergoing, previously dismissed as the object of religious and social opprobrium, was the successful rewriting of melodrama for genteel audiences. Understandably, the reformulating of a genre that was derived from popular forms of entertainment for the urban working class was essential in an age when culture was differentiated between lowbrow and highbrow forms of consumption. Within this context, the success of the society drama associated with the names of Henry C. DeMille and David Belasco proved to be a significant development. A brief but successful collaboration on four domestic melodramas resulted in a legacy that Cecil B. DeMilie would later transmit to the screen as an intertext designed for theatergoers accustomed to social ritual as performance.

A Genteel Audience: Rewriting Domestic Melodrama

Although the relationship between the legitimate stage and early feature film is a subject that needs to be further explored, a brief investigation shows that movie moguls were indebted to the theater not only for intertextual modes of address but also for entrepreneurial practices.[15] Adolph Zukor's vertical integration of the film industry, for example, was similar to organizational patterns established in the theatrical business. Subject to the same

standardized and cost-efficient practices essential to the success of late-nineteenth-century industrial firms, American theater, in contrast to European tradition, depended on box-office revenues rather than state subsidies.[16] When middle-class audiences began to patronize the stage in growing numbers, they represented an increased demand that, together with technological advances, enabled entrepreneurs to establish a monopoly. Upon completion of transcontinental railroad construction, the success of the single-play combination, or road company, featuring Broadway stars in established hits signified the end of local resident companies. Also stimulating the growth of theater as big business was the production of realistic and sensational plays associated with big-name directors and requiring large capital investment for complex machinery, set design, and lighting equipment.[17]

In 1896 Charles Frohman capitalized on these developments by organizing the Syndicate: it monopolized booking agencies serving as middlemen between producers and local playhouses, acquired theater chains in large cities on major railroad stops, and financed productions for the legitimate stage. Programs of theatrical performances show that Frohman anticipated film exhibition practices. Attempting to create a solemn atmosphere in lavish theaters built for cultivated audiences, he provided orchestral performances of works by Rossini, Verdi, and Johann Strauss rather than popular tunes and patriotic airs.[18] So that only the fashionable crowd could attend, ticket prices ranged from $1.50 in the orchestra to 50 cents in the dress circle for reserved seats that had to be secured in advance.[19] At the height of its power in the first decade of the twentieth century, the Syndicate invested in long runs of single plays with type casting and popular stars rather than repertories.[20] When demand shifted from legitimate stage plays to feature film during the 1910s, Frohman joined Adolph Zukor's Famous Players in an attempt to repeat his pattern of marketing mass entertainment.

Since middle-class preoccupation with performance rituals represented a demand that led to the building of fashionable playhouses, melodrama, a popular art staged in "East Side rialtos" as well as in more felicitous venues, was rewritten for genteel consumption.[21] Although the well-made play that came into vogue was still characterized by Dickensian incidents and reversals of fortune, "after 1895 the kidnapped orphans, the ghosts, the papers, the foreclosed mortgages, the providential accidents, the disguises, the rescuing comics, the missing heirs, and even the reconnaissance went into discard; the rhetoric was brought under control; and the sentimentality was tempered." A theatrical form that had largely been abandoned by serious British writers, melodrama was now the province of American playwrights.[22] Consequently, the success of Henry C. DeMilie and David Belasco in formulating society dramas that appealed to the genteel sensibility proved to be a noteworthy achievement. American melodrama arrived on the New York stage in the

1889-1890 season, as Frank Rahill argues, with the success of five native plays, including a DeMille-Belasco collaboration titled The Charity Ball . Unlike three of the productions that were rural in theme and played to less prosperous downtown audiences, The Charity Ball focused on drawing room society.[23] As such, it appealed to the fashionable middle class at the Lyceum, an uptown theater that was also the initial site of the American Academy of Dramatic Arts. Part of a series of four domestic melodramas that DeMille successfully devised with Belasco, the play was based on upper-class characters, drawing room situations, and literate dialogue. In short, it exemplified a more sophisticated melodramatic form crafted for middle-class theatergoers accustomed to social rituals as performance.

Apart from the enactment of social observances related to everyday life, what accounts for the immense appeal of the DeMille-Belasco society dramas? Why were these productions especially relevant to middle-class experience in the late nineteenth century? And what changes were formulated to suit the genre to the sensibility of fashionable theatergoers? As entertainment for the lower orders, melodrama was a mode of expression that dramatized sensational issues such as class conflict in a capitalistic economy. According to Robert Heilman, the "melodramatic form seizes upon the topics that spring up with the turns of history and consciousness—slavery, 'big business,' slums, totalitarianism, mechanization of life, war, the varieties of segregationism. . . . In a more general sense, melodrama is the realm of social action, public action, action within the world."[24] DeMille and Belasco successfully reversed this formula by foregrounding the domestic sphere of courtship, marriage, and the family as a crucible for performance against a related public sphere of societal, financial, or political intrigue. A consequence of the more intimate scale, the consciousness and actions of individual characters acquired more weight in contrast to catastrophic events controlling their fate. Accordingly, the ideological concerns of genteel middle-class audiences who were invested in the privatized family—an institution increasingly threatened by patterns of consumption that nevertheless signified genteel status—were translated into the moral quandaries of the society drama.

Unquestionably, the effectiveness of the society dramas was in large measure the result of Belasco's careful staging and innovative lighting. A producer whose reputation would later enable him to challenge Frohman's Syndicate, Belasco became known for directing ensembles in a naturalistic style that was the result of numerous rehearsals and mise-en-scène integrating actors and sets. As a means of focusing attention on the action of individual characters, he used baby spots and orchestrated subtle changes in mood or atmosphere through "color, intensity, and diffusion of light." Since the box setting, which came into use in the late nineteenth century, consisted of three walls and a ceiling to simulate an actual room, middle-

class audiences could identify with social rituals as performances taking place behind the "fourth wall."[25] For his part, Henry C. DeMilie, acknowledged as a talented dialogue writer, employed the rhetoric of Victorian sentimentalism and religiosity to characterize upper-middle-class relationships.[26] Consider, for example, the exchange of a married couple in The Wife during a moment when their future is in doubt, a scene rendered even more poignant by Belasco's lighting effects:

HEIEN : [Low and tearfully] My husband!

RUTHERFORD : Yes, for by that word, we have the sacred right to know each other's hearts, as they are known by Him, that, knowing, we may help each other. Let us not mistake, as the world so often does, the bond that unites man and wife. [Ring music]

HELEN : Oh! Is it not broken?

RUHERFORD : "Wilt though love her, comfort her, honor and keep her, in sickness and in health, forsaking all others, keep thee only unto her, so long as ye both shall live?" [By this time the moonlight has faded into darkness and the fire has almost died away. He tenderly takes her face between his two hands, reverently kisses her on the forehead, and speaks in a low voice husky with emotion] God—bless—you and give—you—rest. [. . . She slowly turns away from him with bowed head and. . . stops before the door. He goes to the fireplace. She pauses for a moment with the door open, the dim light from the hall falling upon her . . . . Rutherford sinks abstractedly into armchair and gazes into fireplace, where the last flickering spark at that moment disappears][27]

Although theatergoing became part of respectable middle-class culture, the transition from family-centered leisure shaped by maternal guidance to entertainment outside the home, that is, the diminution of separate spheres based on gender, was not accomplished without qualms. A critic who praised The Charity Ball expressed concerns regarding the lower-class morality associated with commercialized amusement:

To demonstrate gently but efficaciously that the human heart still beats responsive to the chivalrous, the gentle, and the wholesomely sentimental, is something that every man and woman who believes in the potency of faith and refinement, and has a spiritual anchorage in a mother and a home will hasten to rejoice discreetly over, for it must be admitted with something like reproach that the theatre of our day oftener reflects the surface discontent and the cheap despair of the saloon and the cafe, than the abiding trust and creative confidence of the home.[28]

Abandoning the pulpit for the stage as a vocation, Henry C. DeMille successfully crafted plays for cultivated audiences by translating Protestant belief in economics as an index of character into the personal terms of domestic melodrama. As a playwright, he facilitated the secularization of evangelical Protestantism, once so essential to middle-class formation, by

employing religious rhetoric to characterize the quotidian. As Peter Brooks argues, "Melodrama represents both the urge toward resacralization and the impossibility of conceiving sacralization other than in personal terms" in a "frightening new world in which the traditional patterns of moral order no longer provide the necessary social glue."[29] Although this generalization was made with respect to revolutionary France, it is also applicable to the urban scene in late-nineteenth-century America. Among the genteel classes, cultural refinement provided the social cement in coded transactions conducted in an increasingly industrialized and secularized milieu. Precisely because social relations in a strange city were fraught with danger and entrapment, as dramatized by the DeMille-Belasco melodramas, the middle class became preoccupied with the semiotics of performance.[30] A critic aware of societal trends noted at the time that DeMilie "was the first to conventionalize to the needs of scenic representation certain phrases and characteristics of American society whose theatric effectiveness . . . had escaped previous writers."[31]

As a sermon, domestic melodrama conveyed the message that middle-class apprehension about the eclipse of the privatized home, itself subject to contradictions, was not unfounded in an age of commercialized leisure. Indeed, the very success of the DeMille-Belasco society dramas attested to the interpenetration of home and marketplace. DeMilie had begun his theatrical career, not coincidentally, as a playreader at the Madison Square Theatre. An establishment situated at the intersection of private and public theatricals, the Madison was associated with famed producer Steele MacKaye, who introduced the Delsarte style of acting, and represented the investment of shrewd businessmen who marketed religious periodicals. Assessing a situation in which a vast middle class found their amusements restricted to "Sabbath-school picnics, strawberry festivals, sociables, and possibly an organ recital," these Broadway investors exploited Victorian sentimentalism to attract a new theater audience. A successful venture meant that "not only did there spring into flourishing existence a new school of dramas, but a new body of theatre patrons."[32] The DeMille-Belasco society dramas thus demonstrated that the feminization of American culture in effect subjected the privatized home to the intrusions of the marketplace. A private theatrical staged in the opening act of the first DeMille-Belasco melodrama, The Wife , provides an apt illustration. Clearly, the nature of commodity exchange or marketplace transactions was not unrelated to modes of self-theatricalization as dramatized in a parlor game wedding:

MRS. A: . . . These private theatricals will be the death of me. I don't remember when I've been so excited. If Nelly had been obliged to act the bride without the wreath, the entire performance would have been ruined. [Enter Silas, L.E.]

SILAS : If ever I permit myself to be cajoled into quitting business again for a holiday, and wheat, choice red, going from 82 1/2 to 83 3/4 and back again!

[Crossing, L.C.] It's bad enough to be roused out of sleep by the boat's arrival at three in the morning, and thrust into the pleasures of Newport half awake—[33]

Although the four DeMille-Belasco productions, The Wife (1887), Lord Chumley (1888), The Charity Ball (1889), and Men and Women (1890), enjoyed lucrative runs on Broadway before going on nationwide tour, critical discourse attests that the success of society dramas, albeit crafted for the educated middle class, raised issues about cultural excellence. As part of the "notable" gathering of the elite described in theater reviews, middle-class audiences participated in a process that simultaneously sacralized and desacralized culture in Arnoldian terms. Cultural refinement, in other words, involved questions of taste that encompassed the intellect as well as appearances maintained by attention to proper deportment, dress, and decor. Yet genteel sensibility became restrained and even tepid as a result of being subjected to rigorous forms of self-representation and social rituals dictated by women. A chorus of male critics thus bemoaned the DeMille-Belasco plays as reasonably entertaining stage fare but trite, vapid, and prosaic. As the New York Sun observed about Daniel Frohman, Charles's brother and manager of the Lyceum Theatre, where three of the four society dramas were staged:

He has induced the more fashionably intelligent people of New York to form fine audiences for his house, and he is aware that they require considerable substance and no offence in their theatrical entertainment . . . . Therefore his pieces must be polite without inanity, humorous without crudity, and strong without coarseness . . . . This is. . . done. . . by having the plays manufactured in his establishment. They are written by Henry G. deMilie, and constructed by David Belasco under Mr. Frohman's own direction. In that way "The Wife" was produced, and last night another result. . . met with a deservedly heartier acceptance . . . . its scenes were laid in the midst of American riches and elegance, and its personages were such men and women as may be found in Fifth avenue homes of opulent refinement.[34]

Similarly, The Illustrated American summed up in an acerbic tone:

For several seasons [DeMille and Belasco] spread upon the boards of theatres of the first fashion and patronage, the mush and milk of mawkish sentiment, sickly humor, and colorless emotion. Silliness, insipidity, and bathos were never before put to such prosperous account. And yet these men addressed themselves to audiences of presumable taste and intelligence. They did not write "for the gallery.". . . Perhaps it is to be regretted . . . . It would have been interesting to note how the quick and pitiless wits of the topmost tier regarded the puerilities and vacuities that delighted the discriminations of box and parquet.[35]

William Winter, the respected New York Daily Tribune critic who later wrote a two-volume biography of Belasco, labeled The Wife "sentimental confec-

tionary and antic farce" and compared it unfavorably with the canonical works of the legitimate stage. Significantly, he referred to photography, construed and dismissed as a mechanistic representation of reality, to criticize the play:

Its scene is laid at Newport, New York and Washington, in the present day; and its dialogue is written mostly in a strain of the commonplace colloquy which is assumed to be characteristic of fashionable society in its superficial mood and general habit. The artistic standard of the authors of "The Wife"—which is the artistic standard of many dramatists—may be inferred from this latter peculiarity. To reflect persons of everyday life and to make them converse in an everyday manner seems generally to be thought sufficient to fill the ambition of the playwright and to satisfy the taste of the public. This was not the limitation of Congreve and Sheridan . . . . That old method of writing comedy . . . appears to have given place to the far inferior and much easier method of literary and theatrical photography.[36]

A year later, the Spirit of the Times expressed a similar viewpoint while invoking Shakespeare in a review of Lord Chumley : "The critics say what ought to be left out. The public say what they like kept in. The manager works at it, alters, cuts, amends, adds, and at last we have such a success as The Wife . . . . This is not playwriting; but, like Mercutio's wound, 'twill serve."[37] Also attuned to the commercial appeal of The Wife was a Tid Bits reviewer who observed:

It will be liked and enjoyed, if not greatly admired, by the run of theatergoers. For say what we will—and no one is more conscious of it than Mr. [William Dean] Howells, for instance, who protests . . . against sentiment and romance—the people, the great big, dear masses, who pay for seats at the theater, and buy the novels, are in their secret hearts hopelessly enamored of sentiment.[38]

Yet the New York Times and the Herald asserted that The Wife was an important American play and a significant contribution to dramatic literaturer.[39]

Although critics cited Shakespeare, Congreve, and Sheridan as models of excellence to whom DeMille and Belasco could not be compared, realist discourse demonstrates that middle-class sensibility, even as it palled within sentimental confines, required artifice. As theater historians point out with respect to forms of realism dominant in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, two variations existed on stage: "romantic realism, in which dramas with idealized subjects are mounted in extremely detailed and historically accurate settings and costume; and true realism, in which plays based on nonidealized contemporary subjects are presented in settings designed to show significant interaction of environment with character and action." The DeMille-Belasco society dramas exemplified the first as opposed to the second category (which also included naturalism) like most

stage fare at the time. Assessing the development of such conventions in theatrical productions, A. Nicholas Vardac points out, "The more romantic the subject matter, the more realistic must be its presentation upon the boards."[40] The legitimate theater, in other words, constituted a forum in which romantic and realist modes coexisted in melodrama that was authentically staged yet appealed to the Victorian sensibility. After concluding that Lord Chumley did not measure up to Shakespeare, for example, the Spirit of the Times added insult to injury by observing, "The play is located in England; but the furniture and fittings and stove in the second act are American." Belasco's sets did elicit rave reviews, however, when an impressive scene in The Charity Ball was staged in a reproduction of a corridor of the Metropolitan Opera House.[41]

Despite the fact that some critics found the DeMille-Belasco society dramas lacking, either in intellectual stimulus or in authentic set design, they would by no means have embraced Ibsen's form of realism. The Graphic stated quite summarily, "If we want unconventional realism, the Lord knows we can go to the novels these days and be satisfied." Charles Frohman's Syndicate, to be sure, displayed little interest in experimentation and exploited works with broad audience appeal. Dissenting actors like Minnie Maddern Fiske, who was married to Broadway producer and New York Dramatic Mirror publisher, Harrison Grey Fiske, championed Ibsen but did not attract large audiences.[42] A New York World reviewer of The Charity Ball voiced critical as well as popular opinion by asserting:

Messrs. Belasco and DeMille have in a measure accomplished in a sentimental way what it is claimed Ibsen is trying to do in a didactic way . . . . "The Charity Ball" retains enough of the essentials of the better part of our serene and wholesome life of the present to preserve it against all the protests of the morbid, the outworn, the pharisaical.[43]

In sum, the DeMille-Belasco society dramas, patronized by the "best people," posed a dilemma in that these works did not exemplify Arnoldian standards as the "best that has been thought and known in the world." As such, middle-class theatergoing, an extension of social rituals performed in elegant parlors, signified the commodification of culture in an age of commercialized amusement. With respect to considerations of gender (as well as class and ethnicity), however, Arnoldian concepts prove inadequate for conceptualizing about culture. At issue, as Jane Tompkins argues, is sentimentalism as the distinguishing characteristic of Victorian female sensibility. An expression of gender conflict, male discourse on society dramas was part of a larger reaction to culture reorganized to suit the social agenda of women committed to the moral legacy of evangelical Protestantism. As works that were "halfway between sermon and social theory," the DeMille-Belasco domestic melodramas expressed a woman's point of view.[44] Ac-

cording to a reviewer of The Charity Ball in the New York Mirror , theatergoing was in effect a social ritual that appealed to female rather than male audiences: "There is. . .just enough pathos to evoke feminine tears, and just enough humor to keep the masculine portion of the audience from falling asleep."[45] Since critics often devalued sentimental discourse as an exercise in female emotions, more to the point was an astute observation in Once a Week :

"The Charity Ball" is. . . the most daring attempt that has ever been made to introduce religion on the stage. The greater portion of the play occurs in a rectory immediately adjoining a church and the text is full of scriptural quotations, while the dialogue is occasionally interrupted by the pealing of the organ and the chanting of hymns.[46]

Several decades would elapse before film exhibitors courted the patronage of respectable middle-class women as a sign of cultural legitimacy. Cecil B. DeMille's legacy of Victorian pictorial dramaturgy as an intertext related to pious and sentimental literature would then stand him in good stead. As demonstrated in What's His Name , the director successfully rewrote domestic melodrama so that it continued to address the ethical concerns of both the "old" and "new" middle class in an era of transition.

Character Versus Personality: What's His Name

As a means of exploring the ethical dilemma of the "old" middle class in an increasingly secularized and consumer-oriented society, Cecil B. DeMille purposely focuses on small-town or village life rather than drawing room society in What's His Name . Since his credentials as an author had yet to be established, the credits announce that the film is an adaptation based on the novel by George Bart McCutcheon, a lesser light among Indiana Hoosiers such as Booth Tarkington and Theodore Dreiser. An author who sold over five million copies of such novels as Graustark (1901) and Brewster's Millions (1903), adapted on Broadway and in feature film, McCutcheon represented the Victorian sentimental tradition pervasive in genteel culture. What's His Name , published by both Dodd, Mead and Grosset and Dunlap in 1911, was a minor effort with strong autobiographical elements because it was written during an identity crisis in part attributed to failed theatrical ambitions. DeMille successfully translated the novel about a small-town soda jerk and a Broadway comedienne, inspired by Minnie Maddern Fiske, into a Progressive Era discourse on gender, marriage, and the family.[47]

A rewriting of domestic melodrama, What's His Name foregrounds inter-textual references to moral dilemmas in society dramas and in social rituals as performance. Pervading the film adaptation is the quality of a play-within-a-play that characterized parlor games such as the private theatrical

11. Advertisement for What's His Name (1914), a domestic

melodrama based on a minor novel by a best-selling author.

staged in The Charity Ball . DeMille thus constructs the mise-en-scène of an opening night, filmed at a Los Angeles theater, so that a high angle shot shows a conductor in the orchestra pit roped off from the audience in middleground and background. The composition of the shot, with the conductor's head peering out of the pit in extreme foreground, is unbalanced until the camera tilts up to reveal an usher leading a formally attired couple down an aisle and to their seats. Another well-dressed couple subsequently arrives and is also seated. DeMille shows the performance that follows by cutting between the proscenium stage photographed in extreme long shots and audience reaction shown in reverse angle shots. Clearly, the filmgoing audience, identified with theatergoers, was being positioned to engage in a series of moral judgments concerning the nature of performance in a scenario about the sanctity of the family.

Drawing attention to the elusive nature of performance, whether in the public or private sphere, Broadway stars Max Figman and Lolita Robertson come to life during the credits as figures in a billboard poster and astonish the puzzled billsticker. Figman had in fact appeared on stage with Robertson before their marriage and acted in productions associated with such noted theatrical producers as Augustin Daly, Charles Frohman, and Harrison Grey Fiske. Since the husband-and-wife team engaged in performance not only as characters wedded in the film but as Broadway stars married in real life, they added another dimension to the film's narrative structure as a play-within-a-play. Audience reception was undoubtedly influenced by fan magazine and news articles publicizing the fact that Figman managed his wife's career and that the couple made a point of traveling together with their children.[48] Such awareness introduced a note of false suspense into a domestic melodrama in which gender roles are dramatically reversed and then reconstituted during an ambiguous conclusion. Partly the result of his stage persona and of his publicity, Figman's portrayal of Harvey as a good-natured but ineffectual soda jerk is much more resonant than McCutcheon's extremely lackluster protagonist.

As an adaptation, What's His Name foregrounds authorial and intertextual issues to reveal the inscription not only of the director but of the novelist and leading actors. Although the contributions of McCutcheon, Figman, and Robertson should be taken into account in attributing authorship, Moving Picture World rightly noted that "the production must have been difficult on account of the condensation, but it is filled with signs of good direction."[49] DeMille's signature is unmistakable in the use of lighting effects, mise-en-scène, and editing to rewrite domestic melodrama as a film genre. A clever construction of the mise-en-scène, for example, conveys the sex-role reversal essential to the film's representation of a lower-middle-class family. Harvey, Nellie, and their daughter Phoebe eat their meals in a cramped apartment furnished with cheap goods. A plain dining table

occupies much of the foreground in a medium long shot that shows a crude hutch beyond the door in the rear wall. After leaving some money to pay for a bill, Harvey exits through the door to his left, while Nellie, clearing the table, looks out the window to see a poster advertising a musical comedy. DeMille apparently simplified, improvised, and eliminated shots while learning his craft because this scene is more revealing as detailed in the script: "Combination of Dining and Living Room: Nellie leaves the window—starts to carry the dishes out. Door bell rings, Nellie goes out, returns with butcher's boy, starts to pay the bill, glances through window, gives him $2.00, explains that she will pay other later. Butcher boy goes out."[50] Nellie, according to the script, is already engaging in selfish and extravagant behavior detrimental to her family's welfare. An inversion of the breakfast table mise-en-scène in the couple's New York apartment, where they have moved so that Nellie may pursue a stage career, is very telling. Although a door in the rear still leads to an adjoining room and a table is still prominently in middleground, the entry is now to the right and the time of day is evening rather than morning. Nellie returns home after a strenuous and discouraging day of rehearsal, while Harvey has busily been preparing dinner. Hanging on the rear wall is a sign, "GOD BLESS OUR HOME," an aphorism that for many Victorians meant material goods rather than spiritual blessings.[51]

DeMille's mise-en-scène in sequences filmed at the theater reveals that although Nellie has escaped the confines of housewifery in an uneventful small town, she is now in the clutches of venal and unethical men. On opening night, she commits a hilarious blunder that singles her out as a crowd pleaser but compromises her personal integrity. The semiotics of female performance was indeed complex and required an interpretation of a spectrum of behavior. Although Victorian women engaged in self-theatricalization in social engagements, such rituals were highly codified as opposed to self-display violating norms of modesty and decency. Acquiring notoriety, as Nellie did, by committing a comic faux pas that drew attention to herself was distinctly unladylike. A comedienne would in fact have found it more difficult than a dramatic actress to claim the mantle of art for her profession. What then does Nellie's performance signify? Clearly, she has embarked on a treacherous course of self-commodification that exceeds proper bounds and may thus be equated with prostitution. Progressive reformers, it should be noted, waged vigorous campaigns against sexual misconduct as a sign of urban change by advocating social purity and social hygiene.[52]

DeMille's inventive mise-en-scène unmistakably represents the precarious situation in which Nellie has become entrapped. A long shot behind the parted curtains of an aisle shows Fairfax (Fred Montague) and the company manager in the foreground as they frame the stage to negotiate a deal. A

repetition of this mise-en-scène backstage underscores Nellie's predicament. Costumed as a clown, she is squeezed in the background between the figures of the two men in dark formal attire as they dominate the foreground. A dialogue title conveys the manager's blunt proposal as he confronts the inexperienced chorus girl: "You'll get more salary and meet Mr. Fairfax, a millionaire, besides." As a matter of fact, the theme of self-display as prostitution was established earlier in the film when Ruby, a chorus girl, reluctantly introduces the manager, intent on engaging an attractive new recruit, to Nellie, by warning him: "If you're on the level, all right, if not, nothin' doin'." Since Fairfax is coded as a paunchy villain who represents plutocratic corporate greed, Nellie has become the object of class as well as sexual exploitation. She must choose, in other words, between domestic confinement that precludes personal and sexual gratification, and public exposure that transforms her into a commodity. Yet genteel reformers would consider Nellie and Fairfax to be equivalent in a setting of commercialized vice as an underworld analogue of corporate greed.[53] The chorus girl, like the millionaire, craves the power, prestige, and luxury that money buys. Attentive to her manager's rule, "No husbands wanted," she ensconces Harvey and Phoebe in suburban Tarrytown, assumes the stage name Miss Duluth, and flirts openly with Fairfax. Actresses were then commonly billed as "Miss" to enhance their attraction for male spectators, surely an aspect of commodification that implied prostitution.[54]

DeMille, who calculated that he spent 20 percent of his time in the cutting room, uses parallel editing to show the deterioration of family life as Nellie becomes a temperamental star and neglects her domestic duties.[55] On Christmas Day, Harvey's plight becomes painfully clear when gifts arrive for Phoebe and the servants while he is ignored. Sensitive to her father's dilemma, Phoebe attempts to console him with a present in a gesture that suggests she is a stand-in for her mother. A cut to Nellie's boudoir reveals the actress, absent from the family hearth even on Christmas, as she compares a modest pin from Harvey with a jewel-encrusted butterfly symbolizing her metamorphosis. Successive close-ups of each pin from her point of view emphasize the lure of temptation to which she succumbs. A cut back to the Tarrytown living room shows Fairfax arriving a short time later in formal dress with cane and bowler. Arrogant and pugnacious, he aggressively dominates the frame, demands agreement to a divorce, and provokes a scuffle. As the two men exchange blows, the Christmas tree is toppled and lies on the floor. Harvey is so distraught that he retires to his room, turns a portrait of Nellie face down on the table, and attempts to commit suicide by switching on the gas lamp. Fortunately, the serviceman arrives to disconnect the utilities so that the unhappy husband awakens, as if in a dream, in a shot with an earlier and happier Blakeville scene superimposed over the bedroom.

Undeterred, Fairfax returns with Nellie who demands custody of Phoebe, but, forced to choose between parents, the child turns to her father. Movers subsequently arrive to place the furniture in storage and cart away the Christmas tree as well as the "GOD BLESS OUR HOME" sign. An insert informs the audience that Harvey has notified his cantankerous Uncle Peter (Sydney Deane), who functions as his alter ego, that he and Phoebe are homeward bound. Parallel editing shows father and daughter traveling in extremely straitened circumstances, while Nellie entertains actresses of dubious character and travels to Reno to obtain a divorce. Symbolically, Harvey and Phoebe are abruptly awakened and ejected from a railroad car but find a ride home on a horse-driven wagon during the last phase of their trip. The journey from New York to Blakeville thus represents a move away from the sinful temptations of city life and a reaffirmation of traditional small-town and rural values.

DeMille's use of lighting effects is as significant as mise-en-scène and parallel editing to convey a didactic message that would appeal to sentimental middle-class audiences. Unlike his later adaptations, such as Rose of the Rancho (1914), The Girl of the Golden West (1915), The Warrens of Virginia (1915), Kindling (1915), and Carmen (1915), in which lighting effects are used throughout to advance the narrative, DeMille singles out specific shots representing the family for what he labeled contrasty lighting. Clearly, he had already used Buckland's talent to his advantage in The Virginian , their first collaboration and his first directorial effort, in campfire scenes absent in The Squaw Man , an otherwise superior film.[56] DeMille recalled years later that his lighting setups were not standard practice and that he had to issue specific instructions to cameraman Alvin Wyckoff:

I was trying to get composition and light and shadow, and I would say to him, "You musn't make this part so light, under the table musn't be light—it should be dark and back corner of the room shouldn't be light—it should be dark." So they all said, "He likes it 'contrasty '"—contrasty!—that was the phrase. I was known as the man who—there were some terrific battles because of that, because that meant expose it for contrast. It didn't mean shadow it, it just meant make the whites whiter and the black blacker.[57]

In What's His Name , DeMille began to codify the use of contrasty lighting to represent moral dilemmas such as those engulfing the family in a society, increasingly preoccupied with consumer values.[58]

The director first uses dramatic lighting effects in an intimate scene following a surprise backstage visit that reveals Nellie dining with Fairfax. At bedtime, Harvey and Phoebe are both lit in the foreground against a darkened background as they recite prayers and exchange an affectionate good-night kiss. Lying on the corner of the bed is a very large doll that serves as a substitute for the child. As both father and daughter assume maternal

functions in Nellie's absence, their relationship is endangered by incestuous feeling, a scenario rendered all the more intriguing by the fact that DeMille cast his only child, Cecilia, as Phoebe.[59] A variation of this mise-en-scène occurs later in a boxcar strewn with straw, signifying religious representations of the Holy Family in Bethlehem, as Harvey and Phoebe take shelter during their long journey back to Blakeville. DeMille moves his camera in closer for a medium shot, in contrast to a preponderance of medium long shots, as once again the father joins his daughter in prayer, tucks her under a jacket, and kisses her good night. Phoebe's gigantic doll occupies the space between them as Harvey falls asleep in the space to her right. All three are dramatically lit against the darkness of the boxcar but not from any naturalistic light source. Lastly, DeMille uses contrasty lighting to recuperate Nellie as a maternal figure after she spurns Fairfax in Reno, a sign of sexual restraint suitable for domestic rather than theatrical life, and responds to a telegram regarding Phoebe's illness. The description of the final tableau in the script is rather pedestrian and shows how much DeMille improvised to achieve his results on film:

Photographer's Studio: Harvey and Uncle Peter nursing Phoebe—Nellie on— Picture—Uncle Peter starts to become violent—Harvey stops him, indicates Phoebe. Nellie comes to other side of couch, kneels over Phoebe. Harvey opposite her—Phoebe tosses—Both start to put covers over her—and eyes meet—Nellie's head goes down on bed—Harvey watching her—Uncle Peter standing at head of bed, shows disgust, turns his back and walks away.[60]

As photographed, all four members of the family are lit in a medium long shot against the darkened backdrop of Uncle Peter's studio. Phoebe sleeps in the foreground as Nellie sits by her bedside to the left. Forming an arc, Harvey leans toward his repentant wife in a conciliatory gesture, while Uncle Peter stands rigidly apart in disapproval as a strong vertical in the center of the screen. Ashamed, Nellie lowers her head so that a broad-brimmed hat obliterates her from the family picture during a moment of restoration, reconciliation, and moral resolution.

DeMille's translation of domestic melodrama as an intertext from stage to screen represents the ethical dilemma of middle-class families caught between the values of self-denial signifying moral character, on the one hand, and personality defined by commodities and performance, on the other. A consumer culture, in other words, meant a rearticulation of gender roles or a remapping of private and public spheres that imperiled sentimental ideals about womanhood. Since What's His Name was based on a novel that, according to one critic, was condensed in the adaptation, a comparison of these parallel discourses shows how each author dealt with the issues of gender, marriage, and the family. McCutcheon's version avoids pronouncements about motherhood that could be interpreted as

saccharine and focuses instead on the inability of the title character to assert his manhood. A small-town soda jerk unable to comprehend the exchange value of commodity production in urban life, Harvey exemplifies sentimental traits such as selflessness, charity, and forgiveness. Nellie, on the contrary, gratifies her whims by obtaining a divorce and marrying Fairfax, as well as assuming custody of Phoebe. She is punished, however, by a fatal illness that provides the occasion for a reconciliation with her magnanimous former husband.

By contrast, DeMille shifts the focus of the narrative to sex-role reversals as these affect the welfare of the child. Although the lighting in the final shot of What's His Name renders ambiguous Nellie's recuperation as a maternal figure, the film nevertheless emphasizes "the potent effect," to quote a reviewer, "of the mother['s] love for her child." Granted, Nellie's rush to Phoebe's bedside may be interpreted as a narrative rupture, but she finally adheres to the dictum that the well-being of children is the purpose of middle-class family life.[61] As Beatrice DeMille stressed in a pamphlet advertising the Henry C. DeMille School for Girls, "only through home life may a rounded development be attained."[62] Significantly, DeMille's first three adaptations, albeit Westerns, have lengthy and meaningful sequences that emphasize adult commitment to the welfare of children, as do his prewar Lasky Company features such as The Captive (1915), Kindling (1915), and The Heart of Nora Flynn (1916). But his better-known Jazz Age sex comedies and melodramas, including Don't Change Your Husband (1919), WhyChange Your Wife ? (1920), and The Affairs of Anatol (1921), focus on companionate marriage or childless couples involved in marital and extramarital misadventures. The absence of children from these later features in effect underscores threats posed to family commitment in a secularized consumer culture.

Although focused on the disintegration of the family under the impact of a sex-role reversal, DeMille's adaptation addresses the crucial problem of masculine identity in an era when revolt against feminization ranged from silly posturing to fascist glorification of warriors. What was the fate of a young man molded according to sentimental principles espoused by genteel women and clergymen in charge of child rearing practices? What were the costs of genteel culture, in other words, for men who did not have the option of escaping into fantasies such as Orientalism or pursuing energetic adventures at home and abroad? Pathetically, Harvey represents the product of a lower-middle-class upbringing, that is, a lackluster white-collar worker with limited aspirations and mobility in a competitive marketplace. Critical response to this Milquetoast figure varied. According to the New York Dramatic Mirror , "the character presented by Max Figman retains a fund of good, manly qualities notwithstanding the burden of indignities." Certainly, Figman is not nearly as passive, inept, and inconsequential as McCutcheon's

unheroic hero. A Hartford Current reviewer, however, describes Harvey as a "weak husband," a judgment affirmed by the film's superego, Uncle Peter, in his disavowal of marriage as a threat to masculine independence.[63]

Since Uncle Peter is a photographer with privileged access to the nature of reality, his censorious behavior in the last scene, which takes place in his studio, renders the resolution as ambiguous as does the lighting. Although he occupies the center of the screen, he also stands apart from the family reunited in the foreground. Perhaps the curmudgeonly bachelor is too uncompromising in his dedication to the small-town values of self-denial, restraint, and thrift. Yet Harvey discovers that assuming a persona means playing oneself false in the only scene in which he enjoys celebrity status as the result of a performance. Dressed like Fairfax and sporting a cane and bowler, he returns to the drugstore to find that news stories about his divorce have portrayed him as a neglectful husband and a ladies' man, a reputation eliciting bravos from curious and admiring townsfolk, Basking in the limelight is cut short, however, by news of Phoebe's illness as a reminder of family obligations. For all his weaknesses, Harvey still personifies sincerity, a trait compromised in sophisticated parlor games and therefore associated with simple village life.

As opposed to Harvey, Nellie represents personality defined by performance and consumption and thus signifies the danger of the marketplace invading the privatized home. She is an actress who not only performs on stage but also portrays the penitent role of the absent mother in the final tableau. Self-theatricalization thereby compromises sincerity even in the back region of the house or in the inner circle of family relations. Yet the ethical conflict of What's His Name is not between the polarities of wealth and sexuality as symbolized by Fairfax, on the one hand, and selflessness as personified by Harvey, on the other. Rather, DeMille rewrites the moral contest as one between character based on the Protestant values of the "old" middle class versus personality representative of a "new" middle class invested in consumption.[64] Consequently, the film yields no easy solutions in terms of closure. According to the conventions of melodrama as a nostalgic reaffirmation of a golden age, the director resolves the moral dilemma in favor of small-town values. What's His Name reaffirms character as defined by "old" middle-class traits such as "benevolence, self-reliance, humility, sincerity, perseverance, orderliness, frugality, reverence, patience, honesty, purity, punctuality, charity," and so forth.[65] But in the final tableau, DeMille aptly sacrifices the moral clarity of a resolution in favor of an ambiguity more consistent with the uncertain values of a middle class in transition.

Given the context of social change in the Progressive Era, DeMille reformulates domestic melodrama in What's His Name to address the concerns of an evolving middle class. A discourse on the erosion of the Victorian practice of separate spheres, the film foregrounds moral issues regarding

the role of women in the family. Since an accelerated shift from a producer to a consumer economy occurred during a period of sustained inflation, debate grew about the wisdom of increased family spending to achieve a more refined standard of living. Essential to the survival of the middle class was the resourceful and prudent housewife who had negotiated transactions in the marketplace long before the advent of a modern consumer culture. She had been enjoined for decades to avoid extravagance and fashion, a sign of social ambition foreign to the "old" propertied middle class.[66] But women were being seduced by an increasing array of enticing consumer goods. Divorce cases, alarmingly on the rise among native-born Protestants, attested to the unreasonable demands and household neglect of wives who wished to increase expenditures. For middle-class audiences accustomed to discourse on the virtues of self-denial as opposed to comfort and refinement, the character of Nellie in What's His Name must have struck a resonant chord. As she is literally effaced by the low-key lighting in the final scene, a tableau that imparts a moral lesson, the actress represents the dangers confronted by the middle-class family in a secular age of increased consumption and leisure.

DeMille's early filmmaking style aptly conveyed such a message, even though a number of interesting details regarding characterization and plot are unintelligible due to a lack of medium shots and medium close-ups. Ruby is characterized as a questionable chorus girl, for example, because she is shopping for cosmetics and wearing a watch on her ankle, details in the script that escape the audience. What registers on account of the high ratio of medium long shots, however, is the intertextuality of feature film, stage plays, and parlor theatricals in Victorian sentimental culture. The director's visual style, specifically mise-en-scène, low-key lighting, and parallel editing, was thus appropriate for the reformulation of melodrama as a sermon for filmgoers accustomed to patronizing the legitimate theater. An unconventional narrative of a sex-role reversal certain to provoke censure, not to mention hilarity, the adaptation served to underscore the continuing need for social convention in middle-class life. As Moving Picture World concluded, "The story . . . has a philosophy that the average spectator will like."[67] DeMille's rewriting of domestic melodrama as a form of Victorian pictorialism thus succeeded as a cinematic articulation of the ideological concerns of both the "old" and "new" middle class at a historical crossroads.