PART TWO

MARRIAGE

Six

Family Strategies and Structures in Rural North China

Mark Selden

Many of the ideas explored here are the product of collaborative research with Edward Friedman, Paul Pickowicz, and Kay Johnson. For background on Wugong and rural Hebei, see Friedman, Pickowicz, and Selden (1991). I am indebted to Richard Ratcliff, who introduced me to computer design and helped conceptualize computer elements of the survey, as well as to Zhu Hong and especially Shih Miin-wen for research assistance in the design and implementation of computer manipulation of the data. Cheng Tiejun, a sociologist, and a native of Raoyang county, who lived and worked in Wugong for several years in the 1970s, has been a source of knowledge, sources, and insight into the issues explored here. Deborah Davis and Stevan Harrell provided insightful critique of successive drafts, as did Edward Friedman, Gail Arrigo, Joan Smith, and an anonymous reader of the penultimate draft.

This chapter explores familial strategies and structures in response to socioeconomic and political changes over two generations in a peripheral region of rural North China. The primary data are household surveys conducted in Wugong village, Hebei, in 1978, at the end of the era of mobilizational collectivism; in 1984, two years after the reform agenda began to transform the village collective structure; and in 1987, when the household contract system had taken root. The surveys, which shed light on familial, demographic, and marital patterns from the 1920s to the 1980s, are supplemented by interviews conducted in the course of more than a decade of fieldwork in this and other villages in Raoyang county and throughout central Hebei. The focus of the study is on familial responses to macro political and economic change over the last half century, notably to the antimarket collectivism and the hukou population control system implemented by a powerful party-state from the 1950s forward, and the contractual and market-oriented reforms and birth control measures of the 1980s.

This study advances and assesses three hypotheses concerning changing familial strategies and structures in rural China in the era of mobilizational

collectivism (the 1950s through the 1970s) and contractual and market-oriented reforms (since the 1980s):[1]

1. Collectivization, by weakening the household as a productive unit, undermined the economic rationale for the extended family. The result was a sharp reduction in average household size and in the number of stem and joint families as smaller nuclear families became the norm in the years 1955-1980.

2. Collectivization, the suppression of private markets, and restrictions on population mobility from the early 1950s through the 1970s, reinforced village involution in two distinct but intertwined senses. First, the ensemble of policies associated with mobilizational collectivism reversed the historical tendency of progressive expansion of the economic and social world of the peasant from the village to the standard marketing community and beyond. Beginning in the 1950s, the world of rural residents contracted back toward the natural village (see Skinner 1964-65). Second, with extravillage income-earning opportunities reduced or eliminated, with rapid population growth continuing through the 1970s, with expansion in the number of labor days per capita, and with collectives absorbing virtually unlimited supplies of labor, labor input increased substantially while marginal productivity of labor declined (see Geertz 1963; Huang 1985, 7-14; Huang 1990, 11-18; Chayanov 1986). This chapter explores some of the manifestations of village involution at the level of the family, particularly the pronounced tendency toward intravillage marriage, shrinking familial size, and simplification of structure associated with mobilizational collectivism in the years 1955-1980.

3. The resurgence of the household economy and the market in the 1980s reversed a number of trends of the collective era, giving rise to a bimodal pattern in household structures. On the one hand, rural household division accelerated as contracts took effect and the central economic role of households was restored. On the other hand, we observe signs of a resurgence of extended families, notably among entrepreneurial households emphasizing nonagricultural activities, capital accumulation, and expanded access to labor power, in ways that invite comparison with pre-land-reform patterns including the relationship between social class and family size and structure. Both cases suggest the growing autonomy and economic role of the household. At the same time, however, the continued strength and penetration of the state is revealed in the enforcement of the one-child (later the tacit two-child) family planning policy.

These theses are examined in relation to Wugong village, with comparisons to patterns observed in other rural regions and communities.

[1] My approach to mobilizational collectivism and the political economy of reform is spelled out in Selden 1992.

Wugong Village

Wugong, a village founded more than thirteen hundred years ago during the Sui dynasty, is located in Raoyang county in south central Hebei, one of the poorest areas of the North China Plain. Although the village is just 120 miles south of Beijing and Tianjin, throughout the twentieth century Raoyang has remained a poor and peripheral region, whose saline and alkaline soil and dearth of above-ground water sources together with periodic eruptions of drought and flood have proved inhospitable to agriculture. Equally important, its primitive transportation and communications—no railroad, poor highways, and lack of waterways[2] —left the region beyond the pale of dynamic metropolitan centers of industry, commerce, and modern thought as they experienced capitalist development and incorporation in the global economy in the first half of the twentieth century.

In the 1940s the region was incorporated in the networks of power that eventually brought the Communist Party to power. Its very peripheral character proved advantageous in insulating the locality from Japanese control and forging bonds of nation and community that linked Wugong and Raoyang to the Party and the army. Raoyang was located in the Central Hebei base area, one of the few plains regions to sustain organized resistance throughout the anti-Japanese war. Beginning in 1943 with a four-household land-pooling group, Wugong villagers embarked on a path of cooperative transformation that would eventually transform a marginal and poor community into a thriving provincial and even a national model of cooperation, before receding into anonymity with the resurgence of the household economy and market forces in the 1980s (Friedman, Pickowicz, and Selden 1991).

In 1978, when research began, Wugong was a large and relatively prosperous wheat- and cotton-growing village with a registered population of 2,552. With per capita distributed collective income of 190 yuan, it was more than 50 percent richer than the second most prosperous of the ten villages that constituted the Wugong Commune, and three times richer than the poorest village. It was also approximately 50 percent higher than China's average 1978 rural per capita income of 133 yuan (Changes and Development in China , 242). Team Three, the largest and most prosperous of three teams and the focus of our household surveys, had a 1978 population

[2] Until 1954 the Hutuo River was Raoyang's lifeline to Tianjin for several months each year. Damming the river eliminated this connection to the major commercial and industrial center in the region. The state's attack on the market and its controls on population movement reinforced the county's isolation. Raoyang was a major casualty of the general prioritizing of irrigation over transportation and of self-reliant production over market ties that characterized national development from the 1950s through the 1970s. A new Beijing-Guangzhou railroad, in the initial stages of construction, is scheduled to pass through Wugong.

of 232 households and 996 people: 514 females, 480 males, and 2 whose gender was not recorded. This was comparable in size to many brigades in rural China, the size being emblematic of the high levels of collectivization ("advanced socialist production relations") maintained since the 1950s. In 1984, as household- and market-oriented reforms were beginning to take root in a region and a village whose leaders long resisted reform, the registered population of the team was 244 households with 939 people: 480 females and 459 males.[3] In 1987 its population had dropped to 845 people in 250 households.

As the village that boasted the oldest continuous cooperative in Hebei, the home of national model peasant Geng Changsuo, and, beginning in 1953, the site of a provincial tractor station, Wugong attained national prominence as a large-scale mechanized cooperative. It sustained its status and special access to state resources through the twists and turns of national policy until the early 1980s. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, as national policies changed, Hebei province remained a bastion of opposition to contractual and market-oriented reforms. Wugong too stood in the forefront of defenders of the collective road that had brought fame and fortune to a once peripheral community. Thus it was not until 1982, following the ouster of its provincial patrons, that Wugong adopted the contract system, and even then the collective continued to play a prominent role in both agricultural and sideline production. Like many other model villages, such as Dazhai and Long Bow, just across the border in Shanxi, Wugong was the last village in its commune to ratify fundamental changes in the collective regimen (Hinton 1990, 31-47; 124-39). Our data capture familial dynamics spanning the decades prior to land reform, the collective era, and the early years of the contractual reforms of the 1980s.

Changing Patterns in Family Size and Structure

Land reform, collectivization, and market closure led to village involution and to important changes in household size and structure. The most important of these changes were the reduction in average household size and

[3] The 1978 officially registered Team Three population was 232 households with 1,053 people. This number included, however, 53 women who had left the team, in most cases by marriage, and in many instances 30-40 years earlier. Our data indicate that they neither contributed financially nor had husbands or children residing in Team Three. We have excluded such individuals from our sample, while retaining others who lived and worked or studied outside the village. These include spouses who work outside and provide financial support to family members in the village, and youth who were studying or serving in the military. All of these maintain important local ties and most are expected to return to the village. In 1978 there were 49 individuals working outside the village, 32 holding jobs in factories, as teachers or cadres, 11 in the army, and 6 studying in universities or technical schools. All of these are included in our Team Three sample.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

number of generations, and the rise to dominance of smaller nuclear families. Data on other communities and regions suggest that many of the demographic changes described below for Wugong reflect broad tendencies found in villages across North China. Our discussion differentiates outcomes specific to a model village from more representative patterns.

Rural surveys of four Hebei villages in the vicinity of Beijing compiled by Sidney Gamble, a large North China sample of 17,581 households studied by John Buck, and Chi-ming Chiao's North China sample of 28,738 households, provide baseline data on household size and structure in rural North China (table 6.1). Gamble found average household size to be 5.1 members, Buck 5.3 members, and Chiao 5.5 members in the 1930s. In Gamble's 1933 sample, 26 percent of households had 7 or more members and 9 percent had 10 or more members (Gamble 1954, 26-27). Twenty-

seven percent of Buck's North China households had 7 or more members, including 8 percent with more than 10 members (Buck 1937, 368). Chiao found that 29 percent of households had 7 or more members, including 10 percent with 10 or more members (Chiao 1933, 17).

In the 1930s, household size correlated closely with landownership and wealth. The large household was economically advantaged, and it was only the prosperous that could sustain large households. Greater size facilitated division of labor, diversification, and accumulation. In his 1927 survey of 400 Dingxian farm families, Sidney Gamble found that those with farms of less than 10 mu had an average of 3.8 members, those with 21-30 mu averaged 6.2, and families with over 100 mu averaged 13.5 members. Per capita landownership and wealth increased with size of farm. For example, there was 1.8 mu of land per person in farms of less than 10 mu, 4.1 mu per person in farms of 21-30 mu, and 9.1 mu per person in farms of over 100 mu (Gamble 1954, 84). In his 1929-33 national survey of 16,786 farms, Buck found that in the winter-wheat gaoliang areas that included Hebei province, the small farm had an average of 4.7 household members, whereas medium-sized farms had 6.0 members, large farms 8.5 members, and very large farms 10.7 members (Buck 1937, 278).

Comparing Wugong's Team Three in 1978 (table 6.2) with North China in the 1930s, we note the much smaller average household size, just 4.3 members, compared with approximately 5.3 members in the earlier period. By 1978 the number of large households with 7 or more members was small despite the fact that a prosperous village like Wugong could sustain relatively large households compared with poorer communities. In 1978, 11 percent of Team Three households had 7 or more members, the largest being 9 members. By contrast, 26-29 percent of North China households in the 1930s samples had 7 or more members, including nearly 10 percent with 10 or more members. By 1978 household size no longer correlated with wealth measured by per capita household income. Size was above all the product of life-cycle timing. Neither labor power, land, capital, nor special skills were any longer decisive factors in determining household opportunity and income. This meant that there was a close relationship between the ratio of labor power to dependency and per capita household income, but virtually no correlation between household size and per capita income. Households with large numbers of young children had low per capita incomes, but as these children moved into the labor force per capita incomes rose. With marriage and household division, the cycle repeated. We hypothesize that this pattern was widespread throughout rural China in the era of mobilizational collectivism.

In 1978, 25 of Team Three's 232 households boasted three generations, and 2 others had four generations. The 5 largest households had nine members, and just 6 others had eight. The four-generation households were

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

those of the deputy Party secretary of the commune and the leader of Team Three. These four-generation households reveal leading Party families living out a contemporary version of the big-family Confucian ideal.

The dominant trend from the 1950s forward, consistent with the logic of collectivization, was from larger to smaller and from complex to nuclear families. The social and economic logic favoring stem and joint families was weakened in a collective milieu. Collectivization reduced the power of the family head over sons once control over land and labor passed from the family to the collective. Stated differently, after 1955 the fortunes of adult males no longer rested as heavily on the goodwill of a father who could assure their incomes and their future. Moreover, the advantages of the large household for achieving prosperity, by facilitating both accumulation and a complex household division of labor, were irrelevant in the collective era. Young men working in the collective earned as much as their fathers through work-point allocations from their teenage years, and there were few outlets for household investment. In short, the economic logic of household accumulation and the extended family was irrelevant in the era of collective agriculture.

To be sure, the collective paid income earned by all members in a lump sum directly to the household head, not to individual earners, perpetuating certain forms of intrahousehold dependency on the family head.[4] The household also remained the primary consumption unit. But sons no longer depended on fathers to provide a share of household land and other property or to organize the household division of labor. Dependence on parents to assure a marriage and provide a home was also reduced if not eliminated in the collective era. In addition, a portion of welfare for the elderly and ill passed from household to collective responsibility, thereby further weakening intergenerational bonds. All these factors strengthened tendencies toward smaller and less complex households, toward reduced intergenerational dependence, and toward earlier household division. This was particularly true in a model village where household production for the market was tightly restricted and the range of collective economic and cultural activities was broad. The fact that model Wugong achieved notable success in birth control by the early 1970s, a decade before most rural communities, strengthened this tendency to reduce household size and complexity.[5]

How widespread was the tendency toward smaller and less complex household structures in rural China in the collective era? Fruitful comparisons in the changing patterns of household size and structure can be made between Wugong in the 1970s and Parish and Whyte's 1973 findings for Guangdong. First, no significant change in household size occurred in Guangdong as a result of collectivization or other factors. Average household size in South China in 1930 was 5.0 members compared with 4.8 members in Guangdong in 1973. By comparison, we have hypothesized that significant reduction in household size in Wugong by the 1970s was a product both of collectivization and of unusual rigor in implementing birth control guidelines in the model village. Why the difference? One important reason is that birth control was not widely propagated or practiced in Guangdong and in much of rural China at the time of Parish and Whyte's 1973 investigation. This situation would change dramatically across the countryside from the late 1970s, bringing north and south into close alignment with respect to fertility. What had changed in Guangdong by 1973 was the fact that both the nuclear family (50%) and the single-person family (12%) had increased sharply in number, improved health care and nutrition reduced mortality, and the number of stem and joint families

[4] A fruitful area for future research is control of the family purse along both gender and generational lines, including savings to assure proper marriages and funerals.

[5] The population of Wugong village increased from 1,700 in 1955 to 2,413 in 1969, a 42 percent increase, or 2.8 percent per year. Between 1970 and 1975 population increased at a rate slightly less than 1 percent per year, from 2,426 to a peak of 2,567, before declining slowly but steadily to 2,533 in 1979. Wugong's 1984 population of 2,552 remained below the 1975 peak level, and population has subsequently remained stable.

plummeted. Compared with 63 percent in the 1930 South China sample, in 1973 in Guangdong only 39 percent were stem and joint families (Parish and Whyte 1978, 132-36).[6] As in Wugong, we hypothesize that the shift to collective agriculture and the declining role of the family as an economic unit was the primary reason for the change in family structure leading to earlier division and reduction in the number of stem and joint families. At the same time, household size did not change significantly, because of continued high birth rates together with mortality rates substantially lower than those prevailing in the 1930s.

Between 1978 and 1987 significant changes occurred in Team Three household size and composition as household division accelerated following the implementation of household contracts. The 1984 survey gives years of household division for 83 of 244 Team Three households. Forty-four households divided in the five years 1979-83. By comparison, just 10 of the surveyed households indicated that they had divided in the decade 1966-75. The high rate of household division in the years 1979-83 constituted a response at the household level to the preparations for, and then the actual implementation of, contractual and market-oriented reforms.

Changes in household size and composition in the wake of partial decollectivization were particularly visible and significant among the elderly. Between 1978 and 1984, the average Team Three household size fell from 4.3 to 3.8 persons, and the number of two-person households increased from 9 to 32. Among two-person households, couples aged sixty-two and older increased from four to nineteen. By the mid-1980s, it was common for both spouses to remain alive, active, and self-sufficient long after their fifties, the time when most households customarily divided.

In 1978 fifteen people over age sixty-five lived alone, often in close proximity to sons or other family support networks. These included three women, ages seventy-nine, eighty, and eighty-three, two of whom continued to earn significant work-points permitting self-support with dignity. Their living alone was nevertheless a sensitive issue. Questionnaires repeatedly recorded the unsolicited information that sons performed household tasks and otherwise supported aged parents who lived alone. Responsibility for the aged remained a family affair. But whatever the assistance rendered, if we look at the utterly bare hovels in which some elderly people resided alone, and observe that such people frequently lacked even tea leaves to add to boiling water when serving a guest, it is difficult to escape the conclusion that in rural China as elsewhere the transition to the nuclear family imposes a heavy price on the rural elderly. By 1984 the number of single-person

[6] Sulamith Potter and Jack Potter, China's Peasants: The Anthropology of a Revolution , 217, found a smaller percentage of Zengbu brigade (Guangdong) households living in stem families in 1980, 25 percent. The joint family form did not exist in this community.

households of those sixty-two or older had dropped to nine, including one seventy-nine-year-old woman and an eighty-four-year-old man.

Between 1978 and 1984 the number of three-person households virtually doubled while the number of five- and six-person households was halved and those with seven to ten members dropped from 26 to 19. The great majority of household divisions in these years took place within two years of marriage, most often at the time of birth of the first (and in these years only) child. Earlier and more frequent household division, together with effective birth control, gave rise in the 1980s to the new archetypal three-person household composed of parents and one child.[7]

These tendencies toward small, simpler, and more homogeneous households were carried further in the years 1984-87. By 1987 there were only two single-person households, and the largest household in the team had only seven members. Between 1984 and 1987 the number of households with seven to ten members dropped from seventeen to just one, and the size of the largest household fell from ten to seven. Household division occurred throughout the 1980s more frequently and earlier than in the 1930s or in the collective era. We see this clearly in a pattern that had no earlier twentieth-century precedent in Wugong or, to my knowledge, in most of rural China. Of the sixty-eight two-person households in 1987, twenty-three consisted of childless couples who married in the years 1980-86. This constitutes a break in two important ways. First, prior to the 1980s, it was extremely rare to establish one's own household before the birth of the first child, and frequently it was only after the birth of a second child, if at all, that the household divided. Our 1978 survey indicated no household composed of a recently married childless couple. Two such households existed by 1984. By 1987, twenty-three childless couples who had married within the previous five years had established independent households.

Prior to land reform, the economic logic of the household economy prevented early household division. At the heart of the family compact was the exchange between the care of aged parents by male offspring and the eventual transfer of land.[8] Collectivization eliminated both the element of land transfer and the household as the organizer of productive activity. The

[7] A return visit in 1991 revealed that Wugong remained a leader in birth control, but with the new relaxed guidelines, more households took the opportunity to have a second child following the birth of a daughter. A second child was permitted four years after the birth of a daughter (or the death of a first child) on condition that one parent accept sterilization. In all but one known case, it was the wife who accepted sterilization.

[8] This formulation of a compact excludes daughters. I tentatively suggest that a weaker and more ephemeral but not insignificant compact rested on parental obligations to nurture and to arrange a suitable marriage for a daughter in exchange for services rendered prior to marriage, after which the allegiance and obligation of a daughter was expected to be to her husband and his family.

household contract system of the 1980s offered young men and women equal and immediate access to their own land—if they established independent households. Moreover, with the village providing land for home construction, growing numbers of young people chose to free themselves from the constraints of parental and mother-in-law authority as quickly as possible following marriage.[9]

A second significant departure from earlier norms of both the republican era and the collective years is that by the late 1980s many young couples were not producing offspring in the first several years of marriage. By contrast, prior to the 1980s, virtually every couple produced a child within the first year or two of marriage. The changes noted here with respect to small nuclear families, autonomous households, and delayed reproduction bring the family in Wugong in the late 1980s closer to prevailing urban patterns in China, and indeed to norms prevailing in industrial societies elsewhere.

Important dimensions of the 1980s economic and social reforms impinge heavily on household size and structure: The household contract system weakened the former collective structure and strengthened the role of households as productive units both in agriculture and in sideline production and market activity. Between 1978 and 1984 the total number of those listed as working or studying outside the village or serving in the military dropped by nearly half to twenty-seven. Outside employees declined by one-fourth from thirty-two to twenty-four. The largest changes centered on outside study and the army. In 1984 no Team Three member was studying outside the village, and the number of those in the army had fallen from eleven to just three. The changes primarily reflect Wugong's loss of status as a model village coinciding with the opening of alternative channels of mobility associated with the private sector and the market, changes that Wugong people were relatively slow to act upon. The drop in the number of youth joining the army may also be a function of the declining prestige and shrinking size of the military in the 1980s.

The 1984 figures do not, however, suggest a trend toward village isolation, involution, and subsistence farming. Quite the opposite. In 1984, 107 households, nearly half of the households in Team Three, listed one or more members who were engaged in nonagricultural economic pursuits, including teachers, factory workers, and contractors in diverse industrial, craft, commercial, and handicraft activities. In 1978, when the collective

[9] Did accompanying policy changes in, for example, access to land and housing for young newlyweds occur at the village level that facilitated the greater autonomy of young people in the 1980s? This is a subject for future research. Here I wish to observe the limits of the present research, which moves between national policy and household behavior but is unable to clarify the important intermediate range of local-level policies, particularly those at the village and county levels, affecting family decisions. Joan Smith drew my attention to these issues.

still held sway, 50 households, just over one-fifth, listed such activities exclusive of unpaid team and brigade political positions. Compared with 1978, many more people engaged in craft and industrial production, provided services, and produced for and sold in the market. While many of these were listed as living and working in the village, in 1984 their work regularly took them outside for commercial and other economic activities. As in the first half of the twentieth century, the Wugong economy was more fully embedded in a wider economic world extending from the standard marketing community to other parts of North China, including Beijing, Tianjin, and beyond to Inner Mongolia and the Northwest.

By 1984, two years after the implementation of household contracts, we observe a bimodal pattern in household strategies. On the one hand, there was continued reduction in household size from 4.3 people in 1978 to 3.8 in 1984. This was the product of large numbers of household divisions in the early 1980s and the continued effects of birth control. Most people lived in nuclear families, and by 1984 the number of four-generation households had further declined from two to none. In 1978, four- and five-person households predominated, accounting for 48 percent of the 232 households; approximately equal numbers of three- and six-person households made up an additional 31 percent. By 1984 three- and four-person households had become the norm, accounting for 134 (55 percent) of the 244 households. The number of households with six or more members plummeted from 64 (28 percent) in 1978 to 32 (13 percent) in 1984. Likewise, the percentage of households with zero or one registered child increased from 45 to 77 percent while the percentage of households with three or more children dropped from 43 to just 16 percent. The number of single-person households fell from 15 (7 percent) to 12 (5 percent) while the number of twoperson households tripled from 9 (4 percent) to 32 (13 percent).

On the other hand, we observe apparently contradictory tendencies at work. Specifically, there was a resurgence of stem, joint, and multigenerational structures as a significant group of households reasserted themselves economically and socially and the reforms stimulated new and diverse individual and family strategies (table 6.3). The striking fact is that in a very brief time, and simultaneous with a sharp drop in numbers of births and in household size in response to the birth control program, the number of stem and joint families nearly doubled from 31 in 1978 to 53 in 1984. Among stem and joint families, the somewhat higher concentration of nonagricultural contracts and members in state-sector jobs as workers, cadres, or teachers underlines a degree of congruence between diversified cashearning economic activity and extended family arrangements. Twenty-seven out of 53 stem and joint families (51 percent) recorded the existence of nonagricultural contracts, extravillage income, or members earning state

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

salaries. The comparable figure for nuclear and one-person households was 80 out of 191 (42 percent).

Our findings concerning the resurgence of extended families in the early 1980s, consistent with the Davis-Harrell hypothesis in the introduction to this volume, run directly counter to the modernization hypothesis that leads one to anticipate that the growth of the market, commodification, and growing cash income would all contribute to strengthening the nuclear family (Goode 1982).[10] Rather, with the opening of the household sector and the market, significant numbers of Wugong people, particularly those with an entrepreneurial bent, chose to reconstitute joint and stem families, reversing the pattern of their sharp decline following collectivization. In just six years, from 1978 to 1984, the number of stem and joint families increased from 31 to 53, even as the average size of family dropped from 4.3 to 3.8 persons. Team Three demographic experience in this respect lends weight to the suggestion by Davis and Harrell in this volume that for the 1980s and 1990s we replace the urban-rural dichotomy with a tripartite division between subsistence farmers, urban collective and state employees, and entrepreneurs in both city and countryside.

One interesting example of the trend toward extended families is provided by the sole Team Three family classified as "landlord." Li Maoxiu, the youngest son of a small landlord, was a resistance activist who rose to head the district children's organization in wartime while his brother joined

[10] William Parish and Martin Whyte, in Village and Family in Contemporary China , 137, observe that, contrary to another modernization hypothesis, in Guangdong in the 1970s, no correlation existed between higher education and incidence of nuclear families.

the Party and the army en route to a government career in Shandong. With his father dead and his brother away, Li Maoxiu was branded a landlord in the 1947 land reform. Isolated, stigmatized, and barred from joining a cooperative, in 1952 Li Maoxiu committed the crime of flight, seeking, with the aid of a seal carved out of a turnip, to begin a new life as a teacher in the Northeast. He was caught and jailed for five years, and following his return to the village lived the life of a pariah. The Lis' only child, a son, married in 1964 at age nineteen. During the Cultural Revolution, to insulate the younger generation from the harassment heaped upon "class enemies," the family divided. Fifteen years later, in the early 1980s, the landlord cap having been officially removed, not only did Li Maoxiu initiate several family enterprises, including long distance trade and the opening of a bakery and a plastic workshop, but he also reconstituted a three-generation stem family. In 1984 the family included his wife, his son and daughter-in-law, and their teenage daughter and two sons. In 1990 the family redivided. Li Maoxiu and his wife lived alone in their original, dilapidated home, a grim reminder of their days of opprobrium. Their son and his wife and children moved into a new home at the other end of Team Three.

The 1987 data indicate that some trends already evident in 1984 have gone further. Average size of household continued to drop from 3.8 members in 1984 to 3.4 in 1987. The drop was particularly precipitous among households with 6 or more members. By 1984 such households had already declined to just 13 percent of the total. By 1987 they had dropped further to just 5 percent, and the number of households with 7 or more members fell from nineteen to one.

At the same time, the hypothesized bifurcating pattern in which the majority form small nuclear households while an entrepreneurial minority favors stem and joint households, appears less pronounced in 1987 than in 1984. While the number of stem and joint families increased significantly between 1978 and 1984, the trend reversed between 1984 and 1987 as the number of extended households dropped from 53 to 46 and their size was reduced. Unfortunately, our 1987 data do not permit clear differentiation between entrepreneurial and nonentrepreneurial households. In any event, the hypothesis concerning correlation between multigenerational extended families and entrepreneurship will require testing against the performance of other and larger samples.

Intravillage Marriage

In the decades following collectivization, the shrinking of the world of the villager from the standard marketing community and beyond to the natural village was manifested in the closing off of extravillage economic, social, cultural, and marital ties. Most rural people found their world restricted to

the confines of the natural village. According to the 1978 survey, of the 985 Team Three residents whose birthplace is known, 771 were born in Wugong and 214 were born outside the village, nearly all of the latter being brides who married in. Famine, political turmoil, war, population pressures, and the hope for better opportunities had led millions of Chinese to flee ancestral villages in search of land, food, and work in the century prior to the founding of the People's Republic. Beginning in 1955, and with particular force after 1960, however, powerful institutional mechanisms associated with collectivization, market controls, and rigorous state enforcement of the hukou system of population control kept rural residents in place in the village of their birth or marriage. Village communities attained extraordinary levels of stability. Only a handful of households settled in Wugong after 1945, all of them prior to collectivization, and in every known case they had familial connections. Of 480 males registered in Team Three in 1978, only 11 were born outside the village, including 3 sons born in the Northeast where both parents were factory workers prior to their forced repatriation to Wugong. The repatriates were among the twenty million industrial workers and family members sent back to their villages of origin in 1962 following the failure of the Great Leap Forward. The combination of collectivization, market curbs, and household registration controls put a brake on the dynamic movement of the Chinese population both within China, where millions had migrated to the Northeast and other areas during the late Qing and the Republic, and abroad. This involutionary pattern too was a facet of the growing isolation of village communities associated with collectivization and population controls. In this respect Wugong's experience was representative of that of rural China.

One important change in marital practice in Wugong concerns intravillage marriage. There were deep structural reasons for the trend toward intravillage marriage following collectivization and market closure. Prior to the 1950s, the standard marketing community not only was the primary locus of trade and cultural activities but also defined the terrain within which most marriage contracts were negotiated. Team Three brides of the previous half century who are listed in the 1984 survey came from some forty villages in Raoyang county and sixteen villages in neighboring counties, nearly all within a ten-mile radius of the village. The combination of collectivization and market suppression substantially changed these patterns. With villagers prevented from buying and selling in the few remaining markets, with the closure of rural fairs and traditional cultural events after 1957, with the penetration of party-state networks deep into village life, and with attacks on old culture, customs, and ideas, including the purchase of brides, most people found their world restricted to the natural village. At the same time that extravillage social and economic ties were severed, with activities largely restricted within the team and brigade, the most valuable

alliances for families struggling to survive shifted to within the village. From work assignments to income, from opportunity for higher education, to a place in the army or the right to build a house, villagers depended heavily on the goodwill of team and brigade cadres who ruled the village. This was the socioeconomic and political basis for the rise in intravillage marriage in rural communities during the collective era, a pattern that spread throughout much of rural China in the 1970s. Village involution was reflected in marital patterns as more and more brides were from Wugong.

There were, in addition, special reasons why Wugong, in this as in many other areas, led the way. As Wugong reaped the fruits of its status as a model village, per capita income soared above the levels of neighboring communities. In the process, marital strategies changed and taboos restricting intravillage or same-surname marriage began to erode.[11] Parents became reluctant to send daughters to live in much poorer villages that traditionally exchanged brides with Wugong. Moreover, with women sharing in the rapidly expanding educational opportunities that made primary school education the norm in Wugong in the 1950s, junior high education in the expanded village school the norm in the 1960s, and even enabled many to graduate from high school in the 1970s (in each instance Wugong was approximately a decade ahead of neighboring communities), young people in the model village had numerous opportunities to meet. Other villages shared in the expansion of education and accompanying social practices, but at a slower pace.

Participation in collective labor and group activities organized by the youth league, militia, and the county government provided important venues in which young people could meet and court. These opportunities were especially numerous in a model village whose youth enjoyed disproportionate opportunities to participate in state-sponsored cultural, social, and political activities. Growing numbers of young people took marital choice into their own hands, often enlisting the services of a matchmaker to legitimate and sanctify their choice after the fact.

There were limits to the related trends toward autonomous and intravillage marital arrangements throughout rural China, particularly constraints imposed by poverty. The poor were at times still forced to enter paired marriages. One young woman in a poor Raoyang village in the 1960s, for example, was forced to abandon her lover, an only child, to accept a blind-exchange marriage that simultaneously assured her brother a bride. Such exchange marriages were illegal, and the Women's Federation sporadically sought to eliminate them. Larger multiple marriages sometimes involved

[11] In Wugong and other multilineage Hebei villages, certain kinds of intravillage marriage, including same-surname marriage, had long been acceptable.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

package arrangements for six, eight, or more young people. The attractiveness of paired and multiple marriages lay in the fact that they often eliminated or greatly reduced costly brideprice and dowry, thus making it possible for the poor to wed. While frowned on by the state, this remained a recourse for poor rural households, for some their only hope to arrange a marriage.

Our 1984 survey reveals significant changes in intravillage marriage patterns related not only to collectivization and market closure, but also to Wugong's prosperity and prominence vis-à-vis neighboring communities. The year 1970 marked the divide with respect to intravillage marriage, and this tendency grew more pronounced with the passage of time (table 6.4). While examples of Team Three intravillage marriage are found as early as the 1930s, just 31 (21 percent) of the 151 brides marrying prior to 1970 were born in Wugong. By contrast, 48 (45 percent) of the 88 brides who married between 1970 and 1984 were born in the village, and 26 of 38 brides (68 percent) who married in the years 1984 to 1986 were born in Wugong. The pattern of intravillage marriage grew stronger throughout the 1980s, despite the fact that villagers again participated in a wider regional economy.

Many other Chinese rural communities followed Wugong in the shift toward intravillage marriage in the collective era. The literature abounds with examples from South China. Parish and Whyte (1978, 171) found that intravillage marriage in Guangdong increased from 3 percent prior to 1949 to more than 20 percent in the 1950s through the 1970s. Potter and Potter (1990, 217), in their Zengbu brigade research (Guangdong), noted an increase in intrabrigade marriage from 10 percent of the total in 1964-68 to 21 percent in 1979-81. In this single-lineage community, intrabrigade marriage had to overcome the taboo against same-surname marriage, which was considered incestuous prior to the 1950s.

Chan, Madsen, and Unger describe a "marriage revolution" in Chen village, Guangdong, during the Great Leap, when several youths dared to defy the taboo on intralineage (and intravillage) marriage and took local

brides of the same surname. In the post-Leap famine, intravillage alliances became the marriage of choice, involving 70-80 percent of the total (Chan, Madsen, and Unger 1984, 188-91). Jan Myrdal provides an anecdotal example from the Northwest, noting that in the 1960s intravillage marriage was commonplace in Shaanxi's Liulin village (Myrdal 1965, 21).

In the 1980s, with the rise of the household contract system and the market, Wugong, slow to shift gears in step with the times, lost its model status. Within a few years neighboring communities rapidly overcame the income and productivity advantages that the model village had long enjoyed. The relative attractiveness of marriage into Wugong under these circumstances declined. Young people nevertheless continued their efforts to secure control over marriage and choose partners from their circle of local acquaintances.

New marital patterns in Wugong were not confined to intravillage marriage. Some Team Three marriages even began to take place within the narrow confines of the team. In 1978 a local schoolteacher and women's activist married the deputy battalion leader of the militia. Both were natives of Team Three. Some Wugong people privately worried over possible adverse genetic consequences of close inbreeding. Wugong had no historical taboo against intravillage marriage or same-surname marriage; indeed this multilineage village had a long history of such marriages. But the village was divided into four incest-taboo neighborhoods, and strict codes had long prohibited marriage within the neighborhood. Two of these areas eventually formed teams one and two, while the third and fourth, separated by a lane, combined to form Team Three.

Geneticists and demographers with whom I have consulted indicate that intermarriage within a community of 600 households (Wugong village), or even 300 households (Team Three), poses no serious threat of birth defects provided close relatives do not marry. Yet China has serious problems of birth defects, and a rash of articles in the Chinese media in the years 1988-90 warned darkly that rural inbreeding had reached serious proportions in the countryside. On December 6, 1988, and January 2, 1989, the People's Daily (overseas edition) cited surveys by sociologist Gao Caiqin to warn of the debilitating consequences of intravillage marriage. On the basis of a study of 1,441 peasant families in six provinces, Gao concluded that evercloser consanguinity in single-lineage villages was "causing population degeneration and undermining social development." Gao found that 30 percent were marrying within their native villages and 51 percent in the township. On January 30, 1989, People's Daily (overseas edition) reported the existence of more than thirty million Chinese with congenital defects and warned that an important source of the problem in remote mountain areas lay in inbreeding. The Impartial Daily , a Party organ published in Hong Kong, presented even more alarming figures in its edition of April 12,

1990. It claimed that China had some fifty million people who were mentally or physically handicapped and again pointed to intravillage and intratownship marriage as a cause. What none of these sources mentioned was the fact that China's hukou system of population control, together with the antimarket collectivism that prevailed until the late 1970s, had strengthened the tendency toward intravillage reproduction.

By early 1989 the state began to act on findings like those mentioned above. Chen Muhua, chair of the Women's Association, told a symposium that the cost of raising children with congenital defects, which many attributed to close kin marriage, was seven to eight billion yuan per year. Chen announced the promulgation of a eugenics law, "Regulations to Prevent Mental Defectives (chidai sharen ) from Bearing Children" in Gansu province (People's Daily , overseas edition, January 30, 1989). The method: forced sterilization. The May 21, 1990, Taiwan newspaper World (Shijie) cited a People's Daily report that Gansu had already sterilized 5,500 of the province's 260,000 mental defectives. Officials stated that most of the rest would be sterilized within the year, and it seems likely that the Gansu sterilization program is a pilot project preparatory to national implementation. It is difficult to imagine a state program more susceptible to political manipulation and human tragedy. What criteria for "mental defectives" will be applied, and by whom?

Neither the broad marital policies of the state nor youth initiatives to take control of marriage challenged the patrilineal, patrilocal marital traditions that were particularly entrenched in North China. (Uxorilocal marriage had long been acceptable for families without sons in the southeast, east central, and southwest but not in the north; Wolf and Huang 1980, 11-15; 94-107; Goody 1990, 106-7.) Virtually the sole state initiative calling patrilineal, patrilocal practices into question in the People's Republic was the 1974-75 campaign pressed by Jiang Qing, with Xiaojinzhuang village in suburban Tianjin as its model. The campaign encouraged intravillage marriage and marriage into the family of a daughter who was an only child. One young man from neighboring Shen county did marry into Wugong at that time, enabling an only child to remain at home to care for her aged parents. The husband benefited by the move to a prosperous model village, doubtless a step up the economic ladder, but entailing some loss of face. With the end of the campaign, the issues disappeared from the political agenda.

The resurgence of the household economy and the market in the 1980s, and the weakening of restrictions on population movement, should reinforce trends toward extravillage marriage as the social and economic world again opens to marketing communities and beyond. Whether these effects will overcome other factors conducive to intravillage marriage, particularly changing patterns of youth courtship, remains to be seen.

Marriage Age

As the place of origin of Wugong brides changed, so too did age of first marriage. The earliest recorded age of marriage in our 1978 survey is that of an eighty-two-year-old poor peasant who married his sixteen-year-old bride when he was fourteen; one woman then in her fifties also married a middle peasant when she was fourteen.

Gamble's study of Dingxian in the 1930s produced numerous examples of much earlier marriages, particularly for boys, than those recorded in Wugong at that time.[12] In a sample of 5,255 rural families, 169 males and 33 females under age fifteen were married, including 21 boys age eleven and under. Girls married as young as age twelve. All but 5 women in Gamble's sample had married by age twenty-one, but as many as 10 percent of males had not married by age thirty-eight. In another study of 515 families, Gamble found the range of ages for first marriage for males to run from seven to fifty-one and for females twelve to thirty-eight (Gamble 1954, 37-41; 58-59). In Buck's 1929-31 North China rural sample of 1,600 married men and 1,760 married women, 58 percent of the men and 86 percent of the women married by age nineteen, including 12 percent of men and 13 percent of women who married prior to age fifteen (Buck 1937, 380). Comparable results were recorded in C. M. Chiao's 1929-31 survey of 12,456 farm families. He found that in North China 62 percent of men and 80 percent of women married before age nineteen (Chiao 1933, 28, 31).

Gamble's 1930 Dingxian sample of 515 families makes clear the high correlation between male marriage age and wealth, using landownership as a gauge for wealth. Among households with less than 50 mu of land, 33 percent of married males wed by age fourteen, and 11 percent first married between the ages of twenty-nine and thirty-five. By contrast, 81 percent of males in households with 100 mu or more of land married by age fourteen and all but five percent married by age seventeen (Gamble 1954, 59).

In another Dingxian sample of 5,225 families, Gamble found that more than 99 percent of females had married by age twenty-one. By contrast, just 60 percent of males married by age twenty-three, and it was not until age thirty-nine that 90 percent of males married (Gamble 1954, 39-40). The great majority of the unmarried 10 percent, virtually all of them males from poverty-stricken families, would never marry. They would face old age without familial support, and their family line would die out, thus violating the filial injunction to maintain the family line.

One measure of the degree of state penetration of village life during the collective era is the success of the campaign to postpone marriage for substantial numbers of rural youth, from the late teens to the early and even,

[12] In the 1930s Wugong was the extreme southwest part of Dingxian prefecture.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

for a period, to the late twenties. By the 1960s, early and child marriages were largely eliminated and very late marriages (over age thirty) as well as the number of men who were never able to wed, were sharply reduced in most of rural China. From the 1950s through the mid-1970s, most Team Three men and women married shortly after age twenty as both earlier and later marriages declined in keeping with state directives and in response to changes associated with land reform and collectivization (table 6.5). The pattern shifted dramatically in the late 1970s. Marriage age for women and men increased on average from twenty-one in the late 1960s to twenty-five in the late 1970s. The explanation for the shifts in marriage age in the 1970s lies in the intense campaign to postpone marriage beyond age twenty-five, one of the pillars of China's birth control strategy at that time.

In the late 1970s campaign to delay marriage, as in so many others, Wugong more scrupulously enforced state goals than did most communities. For model communities, their "capital" was political capital. The advantages models enjoyed in higher income, access to state resources, and prestige were mediated through ties to the state, not the market, although the advantages of model status included higher incomes and privileged access to state resources. We hypothesize that the delay of marriage by five years to the late twenties was unusually pronounced in Wugong and other model villages, although the campaign had an impact far beyond such communities. After 1982 the state relaxed efforts to postpone marriage until the late twenties while continuing to control fertility. With partial decollectivization and the resurgence of the household economy, the state's ability to enforce marital postponement—and much else—generally weakened. The result in Wugong was that the norm shifted back to the early twenties, where it had been since the 1960s.

Older women and men in Team Three experienced a much broader range of ages at first marriage than did younger generations. Of 56 Team

Three women who married between 1920 and 1949 and were alive at the time of our 1984 survey, 20 married between age fifteen and nineteen, 26 between twenty and twenty-four, 9 between twenty-five and twenty-nine, and 1 in her early thirties. Out of 60 Team Three married men whose marriage between 1910 and 1949 is recorded in our 1984 survey, 1 married at age thirteen, 13 between age fifteen and nineteen, and 4 in their thirties. By contrast, every one of the 100 women and 100 men who married between 1970 and 1984 married between age twenty and twenty-nine. The data for the years 1970 to 1984 reveal with particular clarity the effectiveness of state pressures to defer marriage in a model village. In the years 1970-74, 15 men and 14 women married between ages twenty and twenty-four, and just 3 men and 4 women married between twenty-five and twenty-nine. But between 1975 and 1979, as the state called for delayed marriage to age twenty-eight for men and twenty-five for women, the pattern shifted sharply. In the years 1975 to 1979 just 5 men and 8 women married between ages twenty and twenty-four, while 25 men and 22 women married between twenty-five and twenty-nine. In the years 1980-84, state pressures for delaying marriage to the late twenties eased, and the focus of birth control shifted from delayed marriage to contraception and abortion. The pendulum then shifted back toward somewhat earlier marriage. Of the 38 men and 38 women who married between 1984 and 1986, just 4 men and 4 women did so at ages twenty-five to twenty-six while the remaining 34 men and 34 women wed between age twenty and twenty-four.

Our surveys of Team Three contain no examples of destitute males who never married. In Wugong village, from the 1940s, apparently every male could afford to marry, and all, even the physically handicapped, did so. It is not of course the case that following land reform and collectivization all Chinese rural males were able to marry. In the early 1960s, males in poorer households and destitute communities faced continued difficulty in securing a spouse. A vivid example is provided by Duankou village, a poor community a few miles north of Wugong that was devastated during the Great Leap. In the early 1970s just 17 out of 80 men age twenty-five to forty-five had been able to marry. In frustration, unmarried males, led by a former war hero, organized a gang that set out to prevent other village males from achieving the marriages they had been denied. Their method was to launch a rumor war, warning of dire consequences for families of prospective brides who were contemplating marrying into Duankou.

Throughout rural China, land reform and collectivization not only eliminated extremes in inequality of landholding and economic opportunity, but also initiated processes that compressed wide variations in marriage age. This pattern of homogenization in which early and late marriages were virtually eliminated, illustrated with particular clarity in model Wugong, may

be seen, if less sharply etched, throughout much of the countryside during the collective years.

The wide dispersion of marriage age, the inability of significant numbers of poorer men to marry at all, and substantial age differences between spouses, characteristic of rural China in the first half of the twentieth century, gave way in the decades following land reform and collectivization to the homogenization of marriage age in the early twenties. However, the hardcore poor, predominantly those living in chronic deficit areas, remained outside this process.

One other distinctive marital pattern in Hebei counties near Wugong bears mention. A popular local saying went: "A wife three years older is like a brick of gold; a wife five years older looks older than your mother." Sidney Gamble documented the predominant pattern of older wives for Dingxian in the 1930s. In a survey of 766 couples in 515 families, he found that wives were older in 70 percent of cases, husbands in 25 percent. In the case of older wives, the largest number were two to three years older, with a maximum difference of eleven years. Older husbands, however, averaged eight years older, up to a maximum of thirty-one years. Most of these cases involved poor males unable to marry until late in life (Gamble 1954, 45-46).

In Team Three, the greatest age disparity revealed in our 1978 survey was that of a male who took a bride eighteen years his junior in a 1932 union. Six other males, ranging in age from sixty-two to seventy-three, had wives ten to fifteen years younger. An additional thirty-one couples differed in age by five to nine years, with the male being older in twenty-six of these cases. In all but three of the forty-three instances in which the age difference of partners was five or more years, the male was above forty-five years of age, indicating that by the 1950s such marriages had become rare. Since the 1960s, all Team Three marriages have joined partners of roughly equal age; in no case did the difference exceed four years. The trend to marriages among people of comparable age coincided with homogenization in the age of first marriage.

Gamble (1954, 41-43) documented for Dingxian and rural Hebei in the 1930s a class-based pattern of differentiation in which the favored approach for the prosperous was to marry off a son at a very young age, averaging thirteen years for families owning more than 100 mu. Brides in such cases averaged 3.6 years older, to assure that they were ready both to bear children and to care for their in-laws and their child husbands. Wugong data likewise reveal class differentiation in marital patterns, although few men married as young as did Gamble's wealthy scions. The 1978 Team Three survey showed that among surviving couples, twenty-five men who married prior to 1955 had married women five to eighteen years younger. All but

three of these men were classified as poor peasants in land reform (the others were middle peasants). Many of them first married when they were in their thirties or forties, and in one case the groom was sixty years of age. Eleven women married men four to seven years younger. In these marriages, favored by the more prosperous, eight of the husbands' households were middle peasants, and one a landlord. Just two were poor peasants.

Our 1984 survey of Team Three showed that the practice of taking a bride ten or more years younger, which persisted in Team Three into the 1950s, has long since disappeared. On the other hand, forty-three women were two to four years older than their husbands, and thirty-nine men two to four years older than their wives. The pattern of wives two to four years older continued in some relatively recent marriages, including twelve out of twenty-two cases in the years 1974-84. However, in none of the thirty-eight marriages consummated between 1984 and 1986 did the age differential exceed two years. The traditional preference for brides two to four years older appears to have declined. The emerging pattern in the mid- to late 1980s is one of close age parity and a preference for intravillage marriage, with husband and wife of similar age in their early twenties.

Marriage Age and Class

The Team Three survey data provide striking confirmation of class-based differentiation in marital patterns prior to land reform. Wugong was part of the central Hebei base area during the anti-Japanese resistance. Landlord power in this region, with initially very low tenancy rates, was further reduced as a result of wartime reforms prior to the 1947 land reform. Consequently, when class labels (chengfen ) in this village were fixed in 1947, the Party based them on politicized memories of landownership and social relations that purportedly existed in 1936, more than a decade earlier. Only in that way could the Party assure the existence of class enemies to target for struggle and expropriation. The labels nevertheless provide certain clues concerning differential marital patterns among the poorer and more prosperous in the years prior to land reform.

The sample is of twenty-seven males classified as poor peasants, twelve as middle peasants, and one as landlord who were either age sixty by the time of the 1978 survey or had married by 1947. The marital data for the middle peasants and landlords displays the preferred regional pattern of early marriage: eleven of thirteen men married between ages fifteen and twenty to women who were two to five years their senior. By contrast, only four of twenty-seven poor peasants were able to marry by age twenty. Thirteen others were unable to marry until age twenty-five or later, including eight who first married after age thirty. Only four of twenty-seven poor peasant men married an older woman. Sixteen out of twenty-seven of these

poor peasant men married women five or more years younger, including four wrose brides were ten to eighteen years younger.

The 1978 survey data reveal the expected correlation between class designation and marital patterns in Wugong in the years prior to land reform. By contrast, those who married in the 1970s and 1980s display no significant differences based on class designation, for all hewed to state guidelines for marriage in their twenties regardless of class origin or income.

Marriage Age and Party Membership

Marital patterns for male Communist Party members differ significantly from those of non-Party members before and during the era of mobilizational collectivism. The 1978 survey reveals that all fifty-nine male Party members married between ages fifteen and twenty-nine. By contrast, the range of non-Party marriage ages spans the entire spectrum from age fourteen to sixty, with twenty-nine taking place after age thirty. The crux of the issue is the generation that included people who were in their sixties to their eighties at the time of our 1978 survey, since it was among them that later marriage, or no marriage, frequently occurred. Eight of the eleven male Party members age sixty and above had married by age twenty-four, and the remaining three married between twenty-five and twenty-seven. By contrast, the thirty-seven non-Party males for whom marital data is available included ten who married for the first time in their thirties, two in their forties, two in their fifties, and one at sixty. The fact that male Party members who reached marriage age prior to the 1947 land reform all married by age twenty-nine strongly suggests that in Team Three the Party did not recruit extensively from the very poorest strata, that is from marginal households whose sons could only marry very late if at all. Historical research documents the significant role played by prosperous peasants and landlords as well as independent cultivators in the anti-Japanese resistance in Wugong and throughout central Hebei. Such people had the resources to marry at relatively early ages. The Party also recruited among the poor, but rarely from the ranks of the utterly destitute and marginalized.

Party members responded only slightly more loyally than others to the campaign to delay marriage in the years 1975-84. Five of the six Party members who married in the years 1975-80, including two women, waited until ages twenty-five to twenty-eight. The remaining Party member, who was serving in the army, married at twenty-four. Of the eighty-nine non-Party members who married in those years, fifteen men and seventeen women, over one-third of the total, married prior to age twenty-five. Within the context of significant marriage delay for all, Party members tended to hew slightly more closely to state guidelines. But in a model village, nearly everyone conformed to state demands to delay marriage.

Conclusion

This chapter has highlighted changes in family size and structure, marriage age, location of marital partners, and the locus of marital decision in response to powerful state initiatives. Of particular importance are the following: collectivization and population control leading to village involution in the era of mobilizational collectivism, and market-oriented contractual reforms and rigorous birth control measures since the 1980s. The changes associated with the collective era in Wugong and in much of rural China led to homogenization in age of marriage in the range of twenty to twenty-four, a marked shift toward intravillage marriage, shrinking family size, and predominance of nuclear families long before the state succeeded in reducing fertility. Comparative data strongly suggest that these patterns, documented here with respect to Wugong, were widely shared throughout the Chinese countryside. Many trends, particularly delayed marriage and later reduced fertility (the one-child family), constitute direct responses to state policies and priorities. But others reveal the striving of rural inhabitants, and particularly rural youth, to expand opportunities to make autonomous decisions concerning marriage, family, and family division. Certain outcomes, such as the unusually early and high response rate to the state's delayed-marriage campaign, the early and rigorous implementation of birth control, and the trend to intravillage marriage, reflect Wugong's model status, a factor that peaked in the 1950s to 1970s before declining in the early 1980s.

The survey results suggest that the household contract system and expanded opportunity for market and mobility since the 1980s produced significant changes in family and individual marital strategies, including further shrinkage of family size, the existence for the first time of substantial numbers of new couples forming independent households prior to the birth of a child, and the decision to postpone conception for at least several years after marriage. Finally, we note signs of the emergence of a bimodal familial pattern that can best be understood in terms of new class divisions. At one pole we observe small nuclear farm families and at the other a significant number of joint and stem families, many of them engaged in significant entrepreneurial activity.

Seven

Reconstituting Dowry and Brideprice in South China

Helen F. Siu

This chapter is based on fieldwork conducted periodically from 1986 to 1990, funded by the Committee on Scholarly Communication with the People's Republic of China and Wenner Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research. I am grateful for the comments from Deborah Davis, Jack Goody, Stevan Harrell, and participants in the conference on Family Strategies in Post-Mao China, June 12-17, 1990, Roche Harbor Resort, San Juan Island.

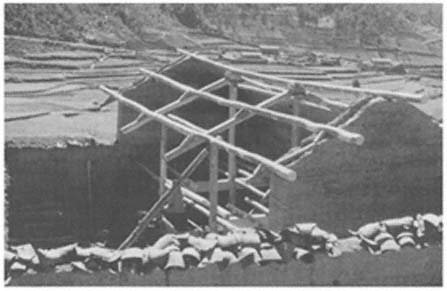

The recent decade of reforms in the 1980s brought drastic changes to Nanxi Zhen, a market town with a rural hinterland.[1] Situated at the heart of the Pearl River delta, connected by easy road and water transport to Guangzhou, Macao, and Hong Kong, it has enjoyed an unprecedented boom.[2] Rows of new houses have mushroomed on the landscape. Some are funded by relatives living in Hong Kong and Macao. Many are built by local entrepreneurs themselves. There is also the ever-growing number of rural enterprises employing young migrant workers on the town's outskirts, accompanied by the bustling businesses on the roads and in shops and restaurants, by the common sight of color television sets, washing machines, hi-fi systems, and videos in private homes, and by the lavish rituals at funerals and weddings.[3]

Family dynamics have taken a sudden turn. Nearly everyone I encoun-

[1] All the local place names in this chapter are pseudonyms. Nanxi Zhen went through a few administrative changes after the revolution. It was an administrative town after 1923, headquarters for the third district of Dagang county. It maintained a market-town status in the 1950s. In 1963 it was made into the Nanxi Zhen Commune. In 1987 it merged with the surrounding Nanxi Rural Commune to become a zhen .

[2] This prosperity has been partly brought about by investments from natives who emigrated to Hong Kong, Macao, and Southeast Asia in the first half of the twentieth century and who have become successful businessmen and industrialists. The particularly successful counties in the delta are Nanhai, Panyu, Shunde, Dongguan, and Zhongshan.

[3] See Helen Siu, "Socialist Peddlers and Princes in a Chinese Market Town," American Ethnologist 16, no. 2 (May 1989), for the economic changes.

tered in town with grown children complained that the young people of today are drunk with the new wealth. They are desperately energetic, but they are also said to be brash, uncaring for their parents, vulgar in their conspicuous life-styles, and lacking moral restraint. Surprisingly, the young people who show little knowledge of the Chinese cultural tradition eagerly participate in lavish funeral and wedding rituals and shoulder most of the expenses themselves.[4]

Town residents also complained that the escalating dowries, some reaching over 10,000 yuan, are ruining those who have daughters to marry off, and that sons and daughters keep most of their wages and bonuses for their own future homes instead of paying for their keep. With an average monthly income of 200-300 yuan, young workers give at the most 40 to 80 yuan per month to their parents. Although the payments from the groom's side averaged 1,000 yuan in cash, the demand on the groom's family to provide a new house for the young couple puts a considerable strain on relationships within the family and leads to intricate maneuvers with town cadres to obtain building sites and materials.[5]

In the villages surrounding the town, which represented an impoverished area in the prerevolutionary and the Maoist period, a similar lavishness is now displayed in the provision of new houses by the groom's side and large banquets.[6] Dowry from the bride's family remains small compared with that of the town, but contributions from the groom's side have increased several times, reaching an average of 2,000 yuan. Poor males are said to have resorted to taking in migrant women from Guangxi province because the amount demanded for marriage to local women has become unaffordable.[7]

Have the terms of marriage gotten out of reach and out of control during

[4] See Helen Siu, "Recycling Rituals: Politics and Popular Culture in Contemporary Rural China," in Unofficial China: Essays in Popular Culture and Thought, ed. Richard Madson, Perry Link, Paul Pickowicz (Boulder: Westview Press, 1989), for the analysis of why young people are actively engaging in ritual activities.

[5] In this area where properties belonging to emigrants had been confiscated in the Maoist era, one strategy today is for the emigrants to claim the properties back for their relatives. Cadres in Nanxi have expressed concern for such a trend because the town government has no resources either to compensate for these properties or to relocate those who are made to vacate.

[6] See also the chapter on marriage practices in a rural community in the eastern part of the Pearl River delta, in Sulamith and Jack Potter, China's Peasants: The Anthropology of a Revolution (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990).

[7] In the 1980s, Nanxi Zhen hired thousands of migrant laborers from other provinces, especially Jiangxi, Guangxi, and Hunan. They filled the lowest level of town factories and also became sharecroppers in the villages. Employment peaked in 1988 with over 15,000. For the pattern of migration, see Helen Siu, "The Politics of Migration in a Market Town," in China on the Eve of Tiananmen , ed. Deborah Davis and Ezra Vogel (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1990).

the recent decade of prosperity? Why do people feel compelled to pursue these ends? What do the marital transfers today tell us about family strategies four decades after the revolution? In addition, the different emphasis on contributions from the bride's and groom's sides in town and village is striking and requires our analytic attention. In pursuing these questions, I aim in this chapter to address theoretical debates in anthropology with regard to marital exchanges, and to use the debates to highlight the complexity of family dynamics and cultural exigencies as several generations of local residents experienced major transformations in the political economy during the last half-century.

Most scholars who work on dowry and brideprice would agree that marital transfers affect and reflect relationships between the generations and between families. Jack Goody starts out arguing that dowry, which establishes a conjugal fund, is a form of "diverging devolution" common to complex stratified societies in Europe and Asia. For purposes of maintaining economic standing, families find it important to advance the status of daughters as well as sons, and so to allocate them a share in the parental estate. He contrasts dowry with bridewealth, a circulating fund common in classless societies. Bridewealth is an exchange among senior men used to establish future marriages, especially for the sibling of the bride. Wealth goes one way, and rights over women another.[8] In Chinese studies (as elsewhere in Europe and Asia), the term "brideprice" applies to that portion of the marital transfers provided by the groom's kin; it is usually part of a wider set of transactions that includes the dowry, the contributions made by the family of the bride and normally destined for the daughter or for the married couple. Goody suggests an alternative phrase, "indirect dowry."[9] Here the term "brideprice" is retained for transfers from the groom's side, whatever their destination. What usually changes is the different weight given to one element as against the other, with higher status groups tending to stress direct dowry and lower ones brideprice, or indirect dowry.[10]

[8] The term "brideprice" has been used to cover two different types of marital transfer. In Africa, it was earlier used for the transaction that passed from the family of the groom to that of the bride, where it was available for the marriage of her brothers or other male kinsfolk; the word was generally abandoned in favor of "bridewealth," since nothing like "price" in the usual sense of the word is involved.

[9] Whether the former gifts are passed on to the daughter or used in the marriage festivities themselves, they constitute even less of a "price" than African bridewealth. However, among some lower-status groups, part or even all of these transfers may be retained by the bride's kin, possibly in compensation for the gift they have provided, possibly as a reserve on which the daughter can draw, possibly for their own use. See Jack Goody and S.J. Tambiah, Bridewealth and Dowry (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1973).