The Board's Rival: the University of California

Wetmore's most prominent enemy in his years at the board was the university itself. The act that created the board also created a department of viticulture in the University of California's College of Agriculture, to be supported out of the same budget that paid for the board's work. Such an arrangement was obviously headed for trouble, and it was not long in coming. The board naturally wished to have a

part in every kind of activity affecting its work; the university, with equal reason, wanted to have full and unobstructed support for its work. In Professor (later Dean) Eugene W. Hilgard, the College of Agriculture had a skilled and bold defender, a worthy antagonist for Wetmore at the board. The two men at first treated each other with guarded respect, then differed, then fell into open controversy. They traded insults and squabbled over almost every point of advice to the industry, and on every occasion of public display. The rivalry came to a head in 1885 over the allocation of a grant of $10,000. This matter was eventually compromised, but the conflict between the two men went on unchanged.[37]

One way or another, Wetmore managed to keep the bulk of the viticultural work and the larger share of the annual appropriation in the hands of the board. The university, handicapped though it was in its rivalry with the board, nevertheless carried out work of great importance at this time. Its contribution to the fight against phylloxera has already been mentioned. Another, and one of its most important and sustained labors was begun almost at once, in fulfillment of plans made by Hilgard. When the university received its money from the state, it immediately constructed a model wine cellar on the campus next to South Hall and began to carry out experimental fermentations with grapes grown around the state. The wines produced thus in small (seven-gallon) experimental batches were carefully analyzed and the results published in a long series of reports covering the years 1881-93. Hilgard's aim was to make what he described as a "systematic investigation of grape-varieties with respect to their composition and general winemaking qualities in the different regions of the state.".[38] The jealousy of the board was not Hilgard's only obstacle in this: he had to convince skeptics that wine made in small test batches could produce representative results—many believed that only wines produced in commercial quantity could do that. Other, more stubborn, doubters held that chemical analysis of any kind was a mere impertinence and that the professor was wasting his time and distracting the industry with his analyses. Hilgard persisted, however, and in the decade of his experiments produced an impressive body of objective information on this vital subject.

Grapes were collected from as many regions of the state as possible. Vineyards at Fresno, Mission San Jose, Cupertino, Paso Robles, and in Amador County were among the most prominent sources: Napa and Sonoma contributed much less.[39] The varieties examined made what was probably a comprehensive inventory of those then growing in the state, and included all of the varieties both red and white now recognized as having commercial value in California—from Aleatico and Cabernet to Tinta Cão and Valdepeñas. When the grapes were received at Berkeley, they were crushed and fermented in the university's experimental cellar under the supervision of F. T. Bioletti, assisted by A. R. Hayne. Bioletti, who ran things under Hilgard's direction, later became the director of the university's wine program and lived to train the first generation of post-Repeal wine scientists in California.[40] Before fermentation the musts were analyzed by Hayne, and after the fermentation the resultant wines were analyzed for sugar, acid, solids, alcohol, and

99

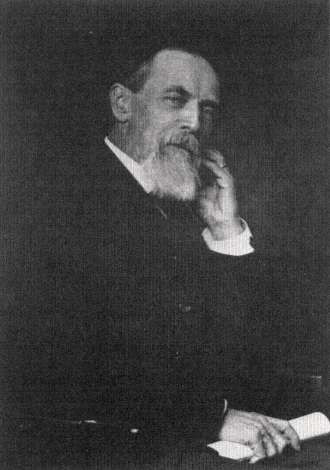

Eugene Hilgard (1833-1916), dean of the College of Agriculture of the

University of California, a leading soil scientist and the head of viticultural

and enological research in California, was the son of an Illinois Lateinische

Bauer who grew a wine called "Hilgardsberger" on his midwestern farm, As

champion of the University of California's work in viticulture and enology,

Hilgard was in frequent conflict with Charles Wetmore, representing the

rival Board of State Viticultural Commissioners. (Bancroft Library, University

of California)

tannin. The reports sometimes went on to add details on the aging of the sample wines and on the results of tastings. On the solid basis of information thus provided, Hilgard and his associates could then make positive recommendations on what to plant and where to plant it. This work, going back to the very earliest days of the university's interest in viticulture, has continued to the present day pretty much along the lines that Hilgard laid down at the beginning.

Of comparable importance to its varietal studies was the university's work on the process of alcoholic fermentation, a subject that biochemists were just then be-

ginning to grasp. Fermentation, of course, had been known and used in a practical way for millennia, but it was known as a mysterious and magical power, more spiritual than material, and all sorts of ritual and superstitious proceedings for directing and controlling it had grown up. During the course of the nineteenth century the problem of discovering the actual mechanisms of fermentation engaged the attention of researchers in many parts of the world; by the end of the century the general understanding of the means whereby the strange transformation of sugar into alcohol and carbon dioxide is achieved had been carried far beyond the limits of the old knowledge. It was, unromantically enough, the demands of the great brewers of beer in Europe that most stimulated research into the subject, but winemakers profited immediately from the results.

The chemical changes produced by fermentation had been well described by Lavoisier in France at the end of the eighteenth century. And the presence of yeasts in fermenting liquids had been known from the late seventeenth century. The unanswered question was, How are yeasts connected with the chemical changes that come about in fermentation? Not until the work of Pasteur in the 1850s and 1860s was this question answered, and then only in a general way. Pasteur was able to show that the chemical changes took place inside the cells of living microorganisms—the yeasts—and that the process was therefore a physiological one rather than, as some had maintained, a mechanical one. Exactly how the yeasts produced the change was far from being explained (it is still a subject of research, though the steps have been worked out in detail); but by the 1890s, when the university began active work in fermentation science, the idea that fermentation depended on the enzymes in the yeast cell was more or less established.[41] Pasteur had also suggested that different yeasts produced different results—some desirable, some highly undesirable—and that it was therefore of the first importance for the winemaker to get the right sort of yeast for his purposes. The yeast of winemaking is, generically, Saccharomyces ellipsoideus , but, just as there are many varieties of the wine grape, Vitis vinifera , so there are many varieties of the wine yeast, ellipsoideus . Fruit brought in from the field is covered with the spores of a multitude of yeasts, and in a fermentation left to itself there is no way to know which strain will prevail. If it is not a sound wine yeast that dominates, the fermentation may not "go through," as the winemakers say, or it may go through to bad results—to vinegar, for example, or to a fluid in which all sorts of undesirable bacteria and molds may develop. Work on isolating and propagating "pure" strains of yeast was first successfully carried out by the Danish scientist E. C. Hansen in the 1880s, with results that allowed a degree of control over the process of fermentation never before possible. By 1891 the French researcher Georges Jacquemin had established a commercial source of pure wine yeasts, and within a few years their use had become a widespread commercial practice in Europe.[42]

The university was quick to take advantage of the achievements of European research by applying them in California. The first experiments with strains of pure yeast began in Berkeley in 1893, with striking results: "In every one of the experi-

ments at Berkeley," Bioletti wrote, "the wines fermented with the addition of yeast were cleaner and fresher-tasting than those allowed to ferment with whatever yeasts happened to exist on the grapes."[43] Samples of pure yeast cultures were sent out to commercial producers in Napa, Sonoma, St. Helena, Asti, San Jose, and Santa Rosa, with equally positive results.

Once the crucial importance of controlling fermentation had been clearly understood, university research was extended into other variables in the process. The role of temperature was investigated, especially the damaging effects of the high temperatures typically encountered in California. Other investigations were made on such topics as the decrease of color in fermentation, the control of temperature through refrigeration, the special problems of high sugar musts (also typical in California), the extraction of color, and the use of pasteurization. The latter process was first made known in 1865 and was quickly adapted in Europe and abroad, but often rather uncritically.[44]

The practical conclusions of all this work were passed on to the industry, and, if the industry was in many cases slow to adopt them (as it was), one could say at least that the California winemaker at the end of the century had, in theory, a mastery of his art that would have astonished the preceding generation. The work of Pasteur and others on the understanding of fermentation had, in one generation, literally transformed the powers of the winemaker to control what he was doing. As the distinguished enologist Maynard Amerine has written, the contributions of biochemistry to wine "have changed winemakng more in the last 100 years than in the previous 2,000," delivering us from a state of things in which "white wines were usually oxidized in flavor and brown in color" and most wines were "high in volatile acidity and often low in alcohol. When some misguided people wish for the good old days of natural wines, this is what they are wishing for."[45]

In retrospect, the work of the university, carried out against the hostility of the board and the skepticism of the state's farmers, had a permanent importance that far outweighed the better-advertised activities of its rival. At the time, however, it may well have been the case that the board's promotional work was more immediately necessary. That both agencies were of the greatest utility in advancing the state of the industry in California is unquestioned; it is a pity only that a better design for their cooperative working could not have been devised.

Though the board was able to keep its university enemies at bay, it had others to face as well. Some winegrowers resented its methods as high-handed and unresponsive; others thought simply that its work was not worth doing, or that, if it was, it was being badly done. The prolonged depression of trade in the wine industry, beginning in 1886, made the board seem clearly ineffective, and the research work of the university appeared all the more valuable by contrast. At the same. time, a reformist campaign against all "useless and expensive" state boards and agencies was under way. The Board of State Viticultural Commissioners could hardly hope to escape indefinitely. Although a bill to abolish the board introduced in 1893 was killed, a comparable bill was passed in 1895.[46] Thus the board came to

an end, and was forced to yield up its assets and properties—including a valuable library of technical literature—to its rival, the university's Department of Viticulture in the College of Agriculture.[47]