17—

CULTURAL, ECOLOGICAL, RECREATIONAL, AND AESTHETIC VALUES

TOWARD A NEW COALITION IN RIPARIAN SYSTEM MANAGEMENT

Recreation Planning As a Tool to Restore and Protect Riparian Systems[1]

Kenneth E. Martin[2]

Abstract.—This paper examines planning strategies which assure the protection of riparian systems while providing for recreation use. A riparian forest adjacent to a densely populated area and subject to intensive recreation use is investigated. The popular recreation activities that occur in connection with a riparian system are identified and methods for controlling recreation use are discussed.

Introduction

Recreation suppliers at all levels of government can successfully provide facilities and opportunities while minimizing adverse impacts on especially susceptible resource elements such as riparian forests and wildlife populations. These protections can only be provided when planners and managers are sensitive to the fragility of natural systems and use proven or innovative visitor control techniques.

Jurisdictions and agencies must remain committed to protecting riparian areas while also providing for recreation opportunities. Agency commitment will occur when there is public support (Smith 1977). Such public support will only be gained if the public has an opportunity to experience and enjoy riparian areas. An example of this was recently described in an article by Marjie Lambert on the South Fork of the American River (SOFAR) project. "A half dozen groups including the American River Recreation Association and the State Department of Boating and Waterways filed protests [over the proposed project] with the [State] Water Resources Control Board because of the impact reduced flows [on the South Fork of the American River] could have on recreation and aesthetics".[3] This example demonstrates that as more people have a greater awareness of riparian areas and their values, the greater will be their indignation at the destruction of our remnant riparian forests.

Riparian Systems Are Attractive Recreation Sites

California riparian systems provide a variety of recreation opportunities, are physically attractive, have a diverse set of plants and animals, have convenient access, and in summer these areas are generally cooler and more pleasant than the adjacent uplands (Roberts etal 1977). Because of this, large numbers of people are attracted to these areas to participate in many of California's most popular recreation activities. Riparian systems are found in many different settings; those most accessible to urban areas receive the greatest recreation use (Geidel and Moore 1981). Therefore, a portion of the American River Parkway that is highly accessible to people in the Sacramento area was chosen as a case study. Observations were made by the author over a period of three months, from June through August 1981.

Intensive Recreation Use

There are two major recreation access points to the American River in the vicinity of Howe and Watt avenues. The areas adjacent to these access points contain sections of riparian forest that are in easy reach of over 1,020,000 people.[4] Of these, 84,000 live within a two-mile radius of these two sites. The popularity of these areas is revealed in an on-site use survey conducted by the County of Sacramento. Together, both access points accommodated in excess of 300,000 visitor days from March 1978 to March 1979 (table 1). Interviews with park personnel and my personal observations reveal that the greatest amount of this use takes place within 46–91 m. (50–100 yd.)

[1] Paper presented at the California Riparian Systems Conference. [University of California, Davis, September 17–19, 1981].

[2] Kenneth E. Martin is Supervisor, Statewide Comprehensive Outdoor Recreation Planning Unit, California Department of Parks and Recreation, Sacramento.

[3] Sacramento Bee. August 18, 1981. River project sponsors seek accord with foes.

[4] California Department of Finance, Population Research Unit. Population estimates for Counties, Report 80 E-2.

of the access points and parking areas.[5] This, of course, does not consider instream uses such as rafting, canoeing, and kayaking or the use of the bicycle trail; it describes the land-based recreation use generated by a typical occupant entering the area by vehicle. Even though there is heavy recreation use, the adjacent riparian forest remains attractive.

Riparian Vegetation and Wildlife

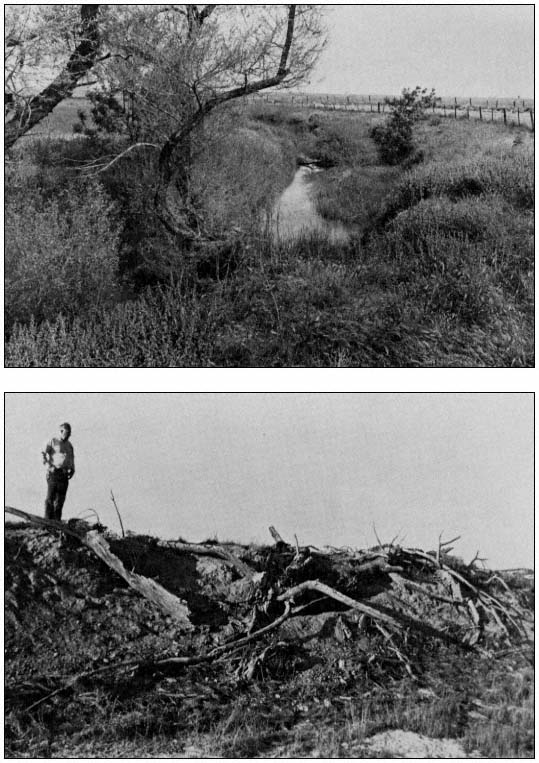

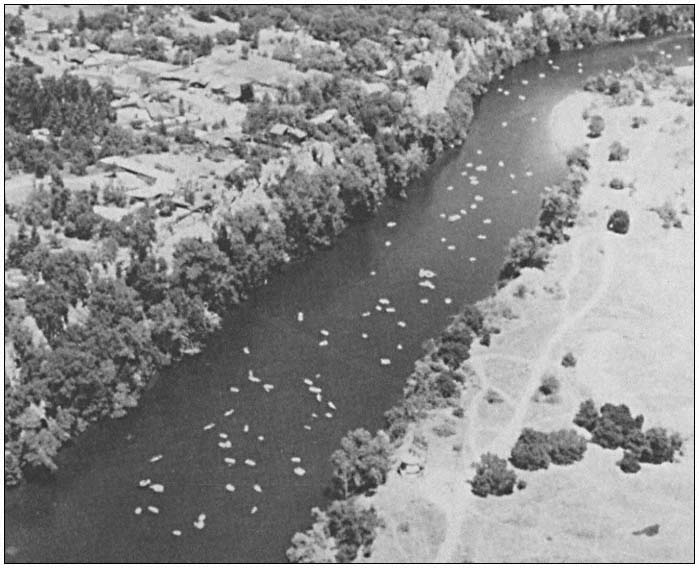

Beyond 46–91 m. of the Howe and Watt Avenue access points, the full diversity of riparian plant and animal associations can be found. Cottonwood, ash, and willows in combination with wild grape, blackberry, wild rose, and other vegetation are essentially in an undisturbed condition. Wildlife is abundant. Beaver, muskrat, and waterfowl can be observed throughout the Howe and Watt Avenue portion of the American River Parkway[6] (fig. 1).

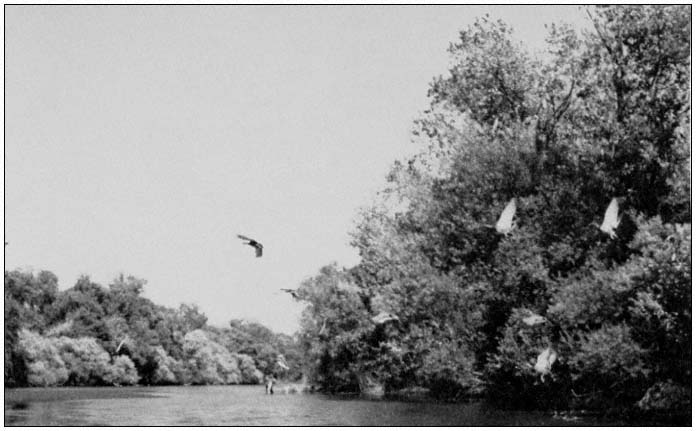

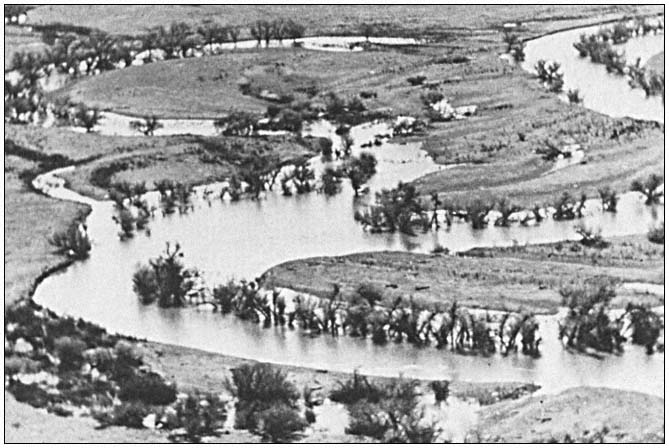

Some access points along the river do show impacts resulting from recreation use. Obvious erosion is in evidence at the popular put-in and take-out sites for boaters particiating in rafting, canoeing, and kayaking. Because these are essentially instream uses, the impact on the shoreside terrestrial areas is minimal and limited to launching and retrieval areas (fig. 2). Popular trails have exposed soil, but this is a localized condition and frequently involves no more than a narrow footpath through a portion of the riverside vegetation.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

[5] Rominger, Gary, 1981. Personal conversation. Chief Ranger, American River Parkway, Sacramento County Park Department, Sacramento, California.

[6] Ingles, Steve, 1981. Personal conversation. Manager, Effie Yeaw Interpretive Center, American River Parkway, Sacramento County Park Department, Sacramento, California.

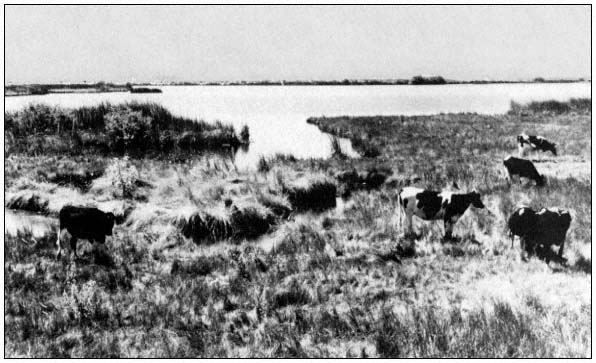

Figure l.

Resident and migratory waterfowl along with other wildlife on the American

River can be found within easy access of over 1 million people.

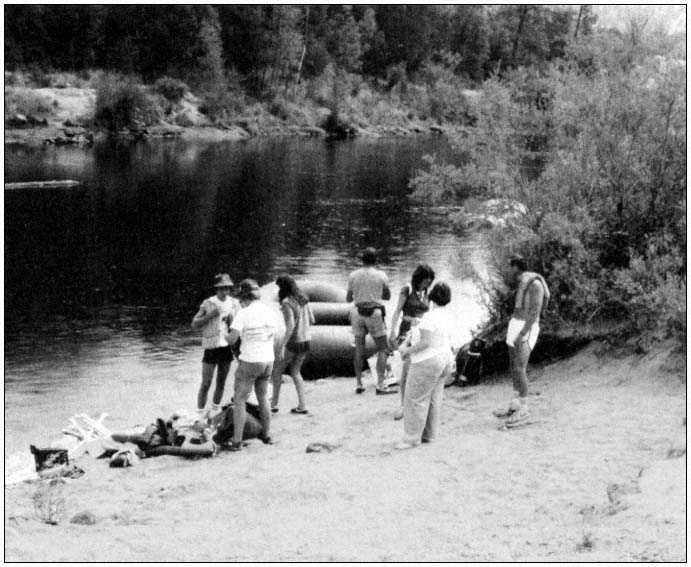

Visitor Control Through Design

Sensitivity to the need for protection of the riparian resource along with the application of good design techniques can be effective in reducing the impact of recreation facilities and use (fig. 3). A key element in the development of that sensitivity comes from interest exhibited by elected officials; and their interest will be stimulated when there is public support.

Before protecting of resource, however, planners should consider it essential to complete a comprehensive resource inventory. Such inventories are presently compiled by the California Department of Parks and Recreation (DPR). Areas extremely sensitive to recreation use should be mapped and recommended for protection; areas more tolerant to recreation use should also be identified. The intensity of recreation use that can be accommodated should be established. The level of demand that exists for certain activities should also be determined, and an assessment of facilities to accommodate those activities should be made. If deficiencies exist, then a planner should develop alternative ways of providing for the projected use. Techniques are available to the site planner for minimizing the impact of use on a sensitive resource (Geidel and Moore 1981). Some subtle and direct controls are discussed below.

Subtle Controls

Among the subtle controls available to the planner to minimize use impact on a sensitive site are the following.

1. Route trails away from sensitive resources.

2. Place vehicle parking lots and access points away from environmentally sensitive areas which are to be preserved.

3. Establish natural barriers between sensitive resources and areas planned for intensive use.

4. Determine carrying capacity of an area and control use by collecting fees, issuing permits, use permits, and limiting the size of visitor facilities.

Direct Controls

Among the direct controls available to the planner are the following.

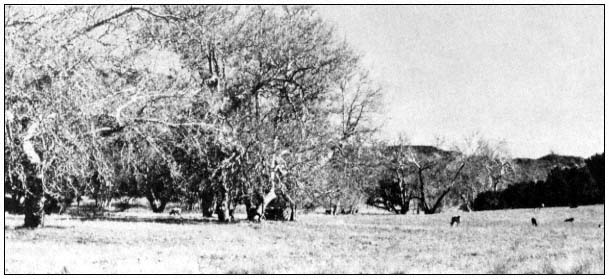

Figure 2.

Intensive use at popular access points prevents natural restoration of riparian vegetation.

1. Encourage desired behavior through interpretive facilities and signs that describe acceptable limits of use, e.g., "Boats 5 MPH," "No Motor Vehicles Beyond This Point."

2. Place physical barriers such as gates and fencing which can be effective and in some cases unobtrusive, in controlling those who ignore signs.

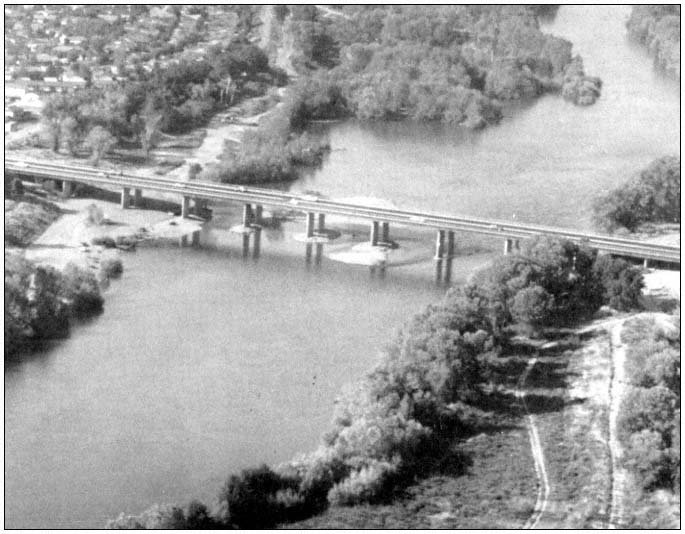

Future Recreation Demand

California's population will continue to grow. Increased pressure from recreationists will affect recreation areas statewide, and riparian systems will not escape that additional pressure (ibid .) (fig. 4).

Those responsible for managing the recreational use of riparian systems must remain aware of those activities that have the least impact on the riparian zone. These include such water-dependent uses as rafting, kayaking, and canoeing which occur most frequently on weekends and holidays during the summer. Other than at access and take-out points, these uses do little or no damage to the riparian vegetation.

Passive recreation activities that are considered water-enhanced, such as nature study, sightseeing, fishing, hiking, sunbathing, and swimming, often have little or no permanent impact on the riparian forest. Speedboating, jet skiing, and off-road vehicle use are more intensive uses and have caused some erosive damage to shoreline and other riparian forest areas.

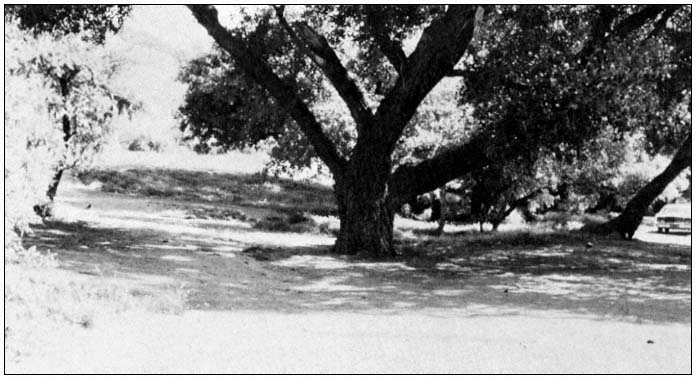

Figure 3.

The proper location of access points and parking lots can restrict the related intensive use without adversely

affecting the riparian vegetation. (Photo courtesy of Sacramento County Park Department.)

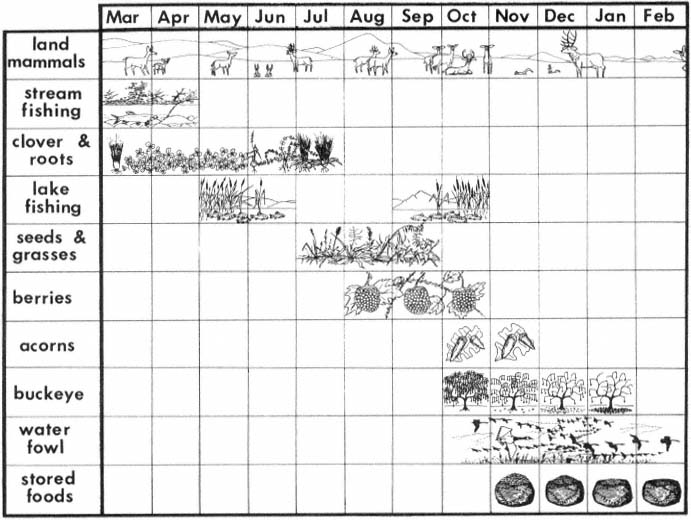

The initial findings of the recently completed Statewide Needs Analysis conducted by DPR reveal that participation in the recreation activities described above and considered water-dependent will increase by 17% by 1990. Participation in those activities considered water-enhanced will increase by 21% (fig. 5, table 2).

Richard Warner has pointed out that the ". . . needs of riparian systems have been seriously 'neglected' by federal, state, and local agencies in the past. . . . Indeed, some agency programs are so designed that riparian system destruction is inevitable, either a) deliberately (e.g., the socalled 'phreatophyte control' schemes), or b) incidentally (dams, diversion schemes, structural bank protection, channelization, 'clean' farming" (Warner 1979).

A significant portion of California's remaining riparian systems exist today because they have been designated and managed as a recreation resource.

Policy Considerations

No single agency or level of government is responsible for protecting riparian systems. Integrated programs that reinforce sound policies must be encouraged among all agencies having landmanaging responsibilities. Some policies successful in the past or recently enacted are discussed below.

Figure 4.

Instream recreation use is becoming increasingly popular on the lower American

River. (Photo courtesy of Sacramento County Park Department.)

Figure 5.

Projected increases in water-dependent

and water-enhanced recreation activities.

(Source: Recreation patterns study, Statewide

Recreation Needs Analysis, DPR.)

Federal Policies

At the federal level, the USDI National Park Service (NPS), USDI Bureau of Land Management (BLM), USDA Forest Service (FS), USDI Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), and others with responsibility for providing recreation opportunities all have policies supporting the preservation and rehabilitation of unique environments while utilizing them for recreation.

The NPS policy for preserving natural zones states that "natural resources and processes remain largely unaltered by human activity except for approved developments essential for management, use and appreciation of the park" (USDI National Park Service 1975). The NPS is guided in the rehabilitation of natural zones by the following policies:

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Removal of man-made features, restoration of natural gradients, and revegetation with native park species on acquired inholdings and sites from which park development is to be removed.

Rehabilitation and maintenance of areas impacted by visitor use including, if necessary, the redesign, relocation, removal—or the provision—of facilities to avoid or to ameliorate adverse visitor impacts.

Restoration to a natural appearance of areas disturbed by fire control activities.

Restoration of landscapes, altered by human activities before park establishment, to a natural appearing state (ibid .).

Further, in developed areas of the National Park System, landscape and vegetation are planned and managed to "the greatest extent possible with the purpose of a given park. The landscape and vegetation should be managed to effect the transition between park development and the terrain, biota, and physical appearance of surrounding management zones commensurate with the requirements and impacts of visitor use" (ibid .).

The NPS strategy for river use, including riparian shorelines, is to be in accordance with the following:

In order to enhance visitor enjoyment and safety, and to preserve environmental quality, the National Park Service will regulate the use of rivers, as necessary, within units of the National Park System.

Using scientific research, the Service will establish the level of boating and related use that each river system can sustain without causing unacceptable changes in the ecosystem or degradation of the environment or the park experience.

A river management plan will be developed for each appropriate unit of the National Park System as an integral part of the resources management plan . . . (ibid .)

Federal policy support for the protection of natural systems and their use for recreation and other purposes is also found in the FS draft Regional Land and Resource Management Plan (USDA Forest Service 1981), individual FS land-use plans, specific resource area plans, and published proceedings; US Army Corps of Engineers (CE) resource development guidelines, rules and regulations, and site-specific plans; and several BLM plans and guidelines such as the California Desert Area Conservation Plan (USDI Bureau of Land Management 1980), and Recreational Carrying Capacity in the California Desert (USDI Bureau of Land Management 1978).

State Policies

Although California has developed a basic wetlands protection policy, there is currently no comprehensive state policy for riparian area rehabilitation and preservation. However, there are numerous state policies guiding the recreation use of natural areas (riparian systems and other unique or sensitive environments).

Among the state policies for recreation are:

Policy No. 3—It is state policy that, in meeting the recreation needs of people, their experience shall be enhanced through the appropriate and sensitive use of natural, historic, and human resources and environments that serve as the source or backdrop for recreation activity. Such resources shall be enhanced, conserved, and protected for the enjoyment and appreciation of present and future generations.

Policy No. 6—It is state policy that lands in public ownership that have recreation potential be considered for availability and accessibility to the people for their recreation, use, and enjoyment, when such activities do not unduly impair the quality of the natural and cultural resources.

Policy No. 9—It is state policy that the interpretation of natural, historic, and archeological resources as recreation resources shall be given high priority in all appropriate state-operated and state-influenced programs (California Department of Parks and Recreation 1982).

More specific natural systems protection policy is found in the Resources Management Direc-

tives for the DPR (California Department of Parks and Recreation 1979) [Appendix A], and the 1980 State Park System Plan (California Department of Parks and Recreation 1980) [Appendix B]. Additional policies and guidelines have been made by the California State Park and Recreation Commission, the DPR, California Department of Boating and Waterways, California Department of Fish and Game, and the California Department of Water Resources.

Local Policies

Many local governments also protect riparian zones for recreation and other values with policies established through zoning ordinances such as the Napa County's Watercourse Obstruction-Riparian Cover Ordinance.

The General Plan for the City of Davis contains many policies that enhance protection of natural systems while permitting appropriate recreation uses. For example, to achieve the preservation and conservation of natural features, the following two policies are listed in the Open Space Element:

1. Preservation of open lands in their natural state in order to ensure their maintenance as wildlife and fish habitats, natural drainage areas, and areas of passive recreation and outdoor education.

2. Preservation and enhancement of the community's natural resources in acquiring and planning parks and other open spaces (City of Davis 1977).

The Biological Resources Conservation portion of the city's Conservation Element has similar objectives such as:

Objective no. 1: Protection and preservation of the habitats and ecosystems of existing natural areas.

Objective no. 2: Restoration and enhancement of natural areas (ibid .).

Each of these objectives contains policies that form a solid base from which a land-use planner can develop concepts for the protection as well as the use of riparian systems.

The examples of riparian protection through recreation development and management policies given here are but a small sample. Literally hundreds of policy statements at all levels of government may be interpreted to accomplish such protection.

Conclusions

Land-managing agencies should approach the protection and preservation of riparian systems with a sensitivity to the provision of recreation opportunities.

Recreation development and use of riparian systems can help in the protection of the systems. Careful development located in already disturbed areas will cause minimal impact, and managed public recreation use can enlighten people to the value of protecting these important resources. The impact from providing acceptable recreation activities is a small sacrifice when the end result can be the development of a constituency that will support the protection of the larger system. Careful planning is essential, with a sensitivity to existing and future recreation impacts along with a sensitivity to the protection and preservation of the riparian systems. Before recreation planning is started, a comprehensive resource inventory should be completed. Based on the inventory, decisions can be made on the areas which have the highest and lowest tolerance for use. These designations aid in determining the types of development, types of recreation use, and carrying capacity of each area.

Recreation demand information should be used in conjunction with resource information to develop a general or master plan. The plan should follow policy guidelines which incorporate the need to protect the riparian system and provide for recreation use. The interest and support of recreationists is an excellent tool to protect riparian systems as an alternative to their destruction from industrial, governmental, residential, and agricultural sources.

Literature Cited

California Department of Parks and Recreation. 1982. Recreation in California issues and actions: 1981–1985. 95 p. California Department of Parks and Recreation, Sacramento.

California Department of Parks and Recreation. 1979. Resource management directives for the California Department of Parks and Recreation, Section 1801–1832.4, Operations Manual, Department of Parks and Recreation, Sacramento.

California Department of Parks and Recreation. 1980. California state park system plan 1980. Department of Parks and Recreation, Sacramento. 239 p.

City of Davis. 1977. City of Davis General Plan (as updated 1978 and 1981). City of Davis, Davis, Calif. 79 p. plus addendum.

Geidel, Marcia, A., and Susan F. Moore. 1981. Delta recreation concept plan. 296 p. California Department of Water Resources, Sacramento, California.

Roberts, W.J., G. Howe, and J. Major. 1977. A survey of riparian forest flora and fauna in California. p. 3–19. In : A. Sands (ed.). Riparian forests in California: their ecology and conservation. Institute of Ecology Pub. 15, University of California, Davis. 122 p.

Smith, Felix. 1977. A short review of the status of riparian forests in California. p. 1–2. In : A. Sands (ed.). Riparian forests in California: their ecology and conservation. Institute of Ecology Pub. 15, University of California, Davis. 122 p.

USDA Forest Service. 1981. Draft regional plan. USDA Forest Service, Pacific Southwest Region, San Francisco, Calif. 108 p.

USDI Bureau of Land Management. 1978. Recreational carrying capacity in the California desert. 115 p. USDI Bureau of Land Management, Sacramento, Calif.

USDI Bureau of Land Management. 1980. The California desert conservation area plan, 1980. 173 p. US Government Printing Office, San Francisco, Calif.

USDI National Park Service. 1975. Management policies 1975. Washington, D.C.

Warner, Richard E. 1979. California riparian study program: background information and proposed study design. 177 p. California Department of Fish and Game, Planning Branch, Sacramento, California.

Appendix A

The following are specific policies selected by the author from the resource management directives of the California Department of Parks and Recreation to illustrate points made in the foregoing discussion (California Department of Parks and Recreation 1979).

(5) Development in State Parks is to be located and designed to protect and enhance enjoyment of the primary resources. In State Parks, the primary purpose for development is to place visitors in an optimal relationship with the resources, for recreational enjoyment and understanding of those resources. In State Parks, resources may not be managed or manipulated to enhance recreational experiences.

(6) Development in State Reserves is limited to facilities required to enable visitors to see, enjoy, and understand the resources. These generally consist of perimeter access, interpretive facilities, trails, and overlooks. In State Reserves, resources may not be manipulated or managed to enhance recreational experiences. Facilities not required for daytime public use and enjoyment of the primary resources are not appropriate.

(7) The Department shall analyze the major resources of each State Park and State Reserve, both existing and proposed, and will recommend boundaries that preserve the integrity of and provide full protection to the natural and scenic resources involved, while assuring the safety of existing or potential developments beyond the boundaries. Every effort will be made to secure funds for acquisition of lands or waters to establish such boundaries.

(15) When important natural, or cultural values are recognized in a State Recreation Unit, procedures to identify and protect such values will be the same as those in State Parks or State Historical Units.

(26) It is an objective of the Department to identify the total framework of environmental and ecological factors influencing the lands of the State Park System, including those arising from human activities, and to promulgate and apply resource management techniques required to negate deleterious human influences, and to achieve the environmental objectives established for the system.

(27) Wherever natural elements are recognized in the State Park System as being of special significance requiring protection and preservation, and regardless of the classification of the units in which they occur, the Department shall recommend the establishment of natural preserves (PRC Section No. 5019.71), to embrace these elements, and to emphasize their recognition and protection.

(29) In the State Park System, perpetuation of values in today's environment may require purposeful guiding of dynamic ecological factors that are constantly undergoing a successional trend through the interaction of natural and extraneous forces. This guidance may not always involve simply the static protection of the features or elements that happen to be a part of the existing environment in any particular period of time.

(32) In order to assure a continuity of effort in management and preservation of resources, it shall be an objective of the Department to prepare for each unit of the State Park System a resource management program or programs, identifying the field management actions required to achieve unit purpose(s) in relation to resources. When approved by the Director, the resource management program or programs for each unit will form the basis for resource management activities at that unit.

(46) In each State Park System unit, environmental quality shall be such that visitors are aware of being in a place of special quality because of their surroundings. Manmade features and their maintenance will have special qualities which, in total, express a feeling of environmental quality that differs from areas where degrad-

ing and undesirable features and intrusions are commonplace.

Appendix B

The following are specific operations policies selected by the author from the State Park System Plan (California Department of Parks and Recreation 1980) to illustrate points made in the foregoing discussion.

Goal 14: Ensure the adequate and proper management and protection of resources within all units of the State Park System.

Policy A—Clearly state the resource management objectives for each unit in the resource element of the General Plan.

Policy B—Monitor and evaluate the ability of unit resources to withstand the impact of visitor use; when necessary, take corrective measure to reduce the intensity of use.

Policy C—Implement appropriate educational and control mechanisms to protect the unit's resource values.

Policy D—Maintain natural habitats where possible and regulate wildlife populations in accordance with the resource management objectives of each unit.

Policy E—Prevent the destruction, deterioration, loss, or other misuses of the geologic, vegetative, or other resources in the natural areas of the State Park System.

Policy F—Protect significant cultural resources (including archeological and historic resources) and their environs from damaging or degrading influences.

Policy G—Minimize environmental degradation of intensively used recreation resources.

Policy H—Permit the use of unit resources by private enterprises for commercial activities, such as films and fairs, only if such uses do not disturb the integrity, and are in accordance with, resource management objectives.

Management and Protection of Riparian Ecosystems in the State Park System[1]

W. James Barry[2]

Abstract.—Preserving California's natural heritage is one of the California Department of Parks and Recreation's three primary missions. As part of the planning process of the department, California's natural ecosystems are systematically identified, classified, and evaluated for statewide significance. Riparian and wetland ecosystems are given a high priority when a parcel of land is being considered for inclusion into the State Park System.

After a project is formulated and the land acquired, an "inventory of features" is prepared. The project is classified as "state reserve", "state park", "state recreation area", etc., depending upon the values identified.

A unit carrying capacity is determined prior to planning or developing recreational facilities. A resource management policy document, the "resource element" of the unit's "general plan", is approved by the Director before substantial recreational facilities planning is done. The general objectives of policies formulated for riparian ecosystems are to restore, protect, and maintain riparian ecosystems in as near a natural state as possible. On- and off-site impacts are discussed with specific examples of resource management problems, policies, and programs.

Introduction

Although managing and protecting riparian ecosystems is not a specific mandate of the California Department of Parks and Recreation (DPR), it is inferred from various legislation incorporated into the California Public Resources Code (PRC) and the California Administrative Code (AC). The three primary missions of DPR are: 1) to preserve California's natural heritage; 2) to preserve California's cultural heritage; and 3) to provide Californians with significant recreational opportunities (Troy etal . 1980). The first two missions often conflict with the third.

Conflicts that cannot be resolved at the staff level are resolved at the administrative level, that is by the Director of DPR or the State Park and Recreation Commission.

The DPR planning process, policies, rules, and regulations pertaining to the management and protection of riparian ecosystems within the State Park System are outlined below. Specific examples of protection efforts and management problems and programs are then given for the State Park System, which comprises more than 250 units totaling around 404,900 ha. (1,000,000 ac.).

Resource Protection and the Planning Process

The planning process begins with an analysis of recreation and preservation deficiencies within the state. In the case of natural values, areas considered to be outstanding or representative examples of natural "landscapes" are considered for acquisition. The state was divided up into nine landscape provinces (Mason 1970). These areas were identified in landscape province studies conducted by DPR over the last 10 years. Unfortunately, in these studies, scenic landscape features were lumped with geologic and biotic features. Recreation potential was a heavily weighted factor in choosing "natural landscape areas" for acquisition. In this planning scheme, one riparian forest biotic community within the Great Valley Landscape Province and one in the Sierra Landscape Province, etc. would be considered adequate to preserve the "riparian landscape," whether it be a riparian community domina-

[1] Paper presented at the California Riparian Systems Conference. [University of California, Davis, September 17–19, 1981].

[2] W. James Barry is State Park Plant Ecologist, California Department of Parks and Recreation, Sacramento.

ted by Fremont cottonwood (Populusfremontii ) or one dominated by California sycamore (Platanus racemosa ).

Since this broad-brush approach eliminated many natural plant and animal communities from consideration, I began devising a multi-hierarchical classification system for California ecosystems, for use in choosing 1980 bond act projects, as well as for the inventory and management of ecosystems in the State Park System (Barry 1979 and in preparation). Using this system, California's natural ecosystems are being systematically identified, classified, and evaluated for statewide significance and preservation status.

Regrettably, the project selection process becomes quite diluted during project evaluation, due to political factors, funding limitations and allocations, etc. Project size is also important. A few larger units are more economical to operate than numerous small, scattered units.

Once a project is selected for acquisitions by DPR, it must be approved by the State Park and Recreation Commission and plans are submitted to the Legislature for approval.[3] The Department of General Services (DGS) appraises the land. Funding of projects and, if necessary, condemnation4 must then be approved by the Public Works Board. Condemnation proceedings often take years; most acquisitions are settled out of court and usually for more than the fair market value of the parcel(s) (fig. 1). This of course, puts willing sellers at a disadvantage. During condemnation proceedings, more than one unwilling seller has clear-cut riparian forests, leveled vernal pools, etc., to spite the State. With the primary natural values of the land in question gone, the State likely will abandon the project.

During negotiations, DGS, generally not being environmentally sensitive, may establish long-term agricultural leases, life estates, etc. with landowners. These leases are often detrimental to the very values the project was meant to protect. When the land is acquired, years may pass before the DGS turns the land over to DPR.

Figure l.

San Louis Island Project, Merced County, contains significant valley oak riparian forests, native

grasslands, and vernal pools. Condemnation proceedings were necessary on some parcels.

[3] Sections 5017, 5018 PRC.

[4] Section 5074.3 PRC.

During this interim period many resource values may be exploited. For example, in the riparian zone of Burton Creek State Park, Placer County, the trees were cut for firewood while the state park rangers stood by, helplessly, with no jurisdiction over state-owned land that was to become a natural preserve!

Once land is turned over to DPR, an "inventory of features" is required for classification of the new unit.[5] DPR staff submits an inventory of features report and recommendations for classification and naming the unit to the State Park and Recreation Commission.[6] The four basic categories of classification are state reserves, state parks, state recreation units, and state historical units.[7] Riparian ecosystems can occur in all of these classifications; more important examples are set aside in subunits such as natural preserves or state wildernesses.[8] State reserves, state wildernesses, and natural preserves are the most restrictive use classifications. Examples of units designated especially for protection of riparian ecosystems include Burton Creek and Woodson Bridge (Tehama County) natural preserves. Other areas are currently being considered (fig. 2).

Figure 2.

The Miller Creek watershed in Salt Point State Park (Sonoma

County) has been recommended for natural preserve status

(Michaely et al .1976). This watershed contains Oregon alder

(Alnus oregona ), riparian forests and the southernmost

population of pygmy cypress (Cupressus pygmaea ).

Classification establishes, in broad terms, the kind and intensity of recreational use and development allowed within a unit. Attendance is to be held within limits established by a carrying capacity survey, established prior to any developmental plan.[9] The survey shall include such factors as soil, moisture, and natural cover.[10] Unfortunately, these mandates have been largely ignored, or carrying capacity has been determined by the size of the land area available for potential recreation development (the size of the parking lot rather than ecologic sensitivity has often determined unit carrying capacity).

The most important phase of the planning process for a unit is the general plan phase. Following classification or reclassification of a unit and prior to the development of any new facilities, DPR must prepare a general plan or revise any existing plan. The general plan consists of elements that evaluate and define proposed land use, facilities, operation, environmental impact, management of resources, and any other matter deemed appropriate.

With respect to the protection of riparian ecosystems, the resource element of the general plan is the most important document of the planning process since it evaluates the unit:

based upon historical and ecological research of plant-animal and soil-geological relationships, and shall contain a declaration of purpose, setting forth specific long-range management objectives for the unit consistent with the unit's classification . . . and a declaration of resource management policy, setting forth the precise actions and limitations required for the achievement of the objectives established in the declaration of purpose" (Section 5002.2 PRC).

"In order that it shall act as a guide and constraint, the resource element will be prepared, made available for public comment, and approved by the Director before substantial work is done on the other elements of the plan" (Section 4332 AC).

However, substantial work is usually done on the development of units prior to the general plan. Time and budgeting constraints seldom allow adequate research to make wise, indepth resource management policies. Further, the implementation of resource management policies is often costly and difficult, if not impossible. This is especially true where off-site impacts are present. Once the general plan is approved by the State Park and Recreation Commission, resource management policy is implemented through specific resource management programs which must be budgeted for two years in advance. Current funding for the statewide resource management program amounts to between $0.50 and $0.60 per acre per year of State Park System lands. In con-

[5] Section 5002.1 PRC.

[6] Section 5019.50 PRC.

[7] Sections 5019.65, 5019.53, 5019.56, and 5019.59 PRC, respectively.

[8] Sections 5019.7 and 5019.68 PRC.

[9] Section 5001.96 PRC.

[10] Section 5019.5 PRC.

trast, the approximate equivalent $500,000 has been approved for working drawings for the recreational development of a single unit (Salt Point State Park). Working drawings are not done by DPR, rather they are contracted out to the Office of State Architect, which is less sensitive to environmental constraints and cultural or natural preservation.

Management of Riparian Ecosystems

Resource management problems encountered in riparian ecosystems are due to a number of onand off-site impacts. Off-site impacts are generally the more serious and less controllable of the two. Critical off-site impacts include watershed and hydrologic disturbances such as logging, stream or lake modification (dams, channelization and controlled flow), wildfire, urbanization, off-road vehicular activity, and cultivation.

Off-Site Impacts

The most tragic and dramatic example of offsite impacts is the ongoing destruction of the Bull Creek watershed within Humboldt Redwoods State Park, Humboldt County. At the confluence of Bull Creek and the South Fork of the Eel River is one of the most magnificent stands of coast redwoods in the world—the 3,640-ha. (9,000-ac.) Rockefeller Forest. Prior to the recent discovery of a tree slightly taller in the Redwood Creek watershed the world's tallest tree was thought to be in this pristine grove. In the first part of this century the grove was purchased by DPR with funding provided by private sources (John D. Rockefeller). Meanwhile, logging was occurring in the upper watershed. The entire watershed, with the exception of the state park property, was clear-cut and the slash burned.

The winter of 1955–56 brought heavy rains and flooding to northern California; severe erosion and stream channel destruction resulted. The riparian alder and willow thickets along the stream channel were completely washed out, and the magnificent riparian redwood giant forests of the alluvial flats were undercut; numerous ancient trees toppled into the stream, clogging the channel, which caused further undercutting. The stream channel area was completely devastated, quadrupling in size. The 1964 floods further widened the channel (fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Bull Creek "shoofly" in Humboldt Redwoods

State Park, February 1965.

DPR began a massive cleanup, erosion control, and stream channelization project. The channel was riprapped and a long-term resource protection program was initiated which included various types of research (fig. 4). Volunteers replanted trees in the watershed and riprapped banks were revegetated with riparian species (willows and alders stuck or planted between the rocks). To date more than $2.28 million has been spent on the Bull Creek Project.

We are now beginning to look at similar, although less critical, riparian forest losses along the South Fork of the Eel River; however, the upper Bull Creek watershed is still unstable, with massive slides occurring each winter (fig. 5). No feasible solution to these slides has been suggested.

Channelization of the Sacramento River has caused serious bank erosion problems in Woodson Bridge State Recreation Area. The stream channel is undercutting streamside riparian vegetation and has cut through the levee. The channel upstream has been riprapped in such a way that the current is directed into an unriprapped bend within the unit. Further, if this bank is riprapped to protect the valley oak riparian woodland, the current will be deflected to the opposite bank where a fine cottonwood riparian forest is located in Woodson Bridge Natural Preserve. The preserve is a nesting area for the rare Yellow-billed Cuckoo. Various bank protection measures are currently being investigated.

Wildfire has caused numerous types of damage to streamside riparian ecosystems. The combination of an extremely hot wildfire (the Molera Fire of August 1972) and heavy rainfall caused mudflows in the Big Sur River watershed (Cleveland 1973). Between mid-October 1972 and mid-February 1973, mudflows were generated by heavy and occasionally intense winter rains falling on steep, fire-denuded slopes of the Santa Lucia Range. Damage from mudflows and floodwater was predominantly confined to riparian zones along the lower courses of Pheneger, Juan-Higuera, and Pfeiffer-Redwood creeks. Although extensive damage occurred to property and to the coast redwood riparian forests, investigations of coast redwood root systems have shown mudflows to be a recurring natural phenomenon (fig. 6). Thus, from an ecosystem management standpoint no action would be taken; however, burned-over watersheds

Figure 4.

Riprap in Bull Creek, Humboldt Redwoods State Park, October 1971.

Figure 5.

Slide area in the upper Bull Creek watershed,

Humboldt Redwoods State Park, October 1971.

Figure 6.

Mudflow material in Pfeiffer-Redwood Creek,

Pfeiffer Big Sur State Park, January 1973.

were reseeded and gabions installed in the Big Sur River to try to protect the town of Big Sur, where extensive damage occurred.

Wildfire followed by flash flooding has caused obliteration of desert riparian ecosystems (fig. 7).

Among California's coastal dune systems are fine riparian ecosystems located in moist-dune swales and adjacent to dune-formed lakes. These micro-ecosystems are characteristically dominated by willow thickets in dune swales and alder thickets along lake banks.

Figure 7.

Sedimentation and erosion in Hell Hole Canyon,

Anza-Borrego Desert State Park, San Diego County,

following wildfire and flash flood, April 1978.

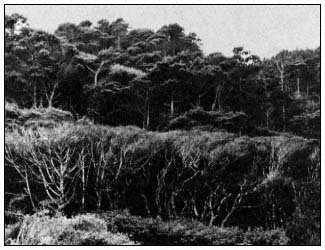

The Ten-Mile River dune system is located in MacKerricher State Park (Mendocino County). Prior to acquisition, the dune system was open to off-road vehicles. Also, by the turn of the century most of the Ten-Mile River had been logged. With the heavy erosion that followed, through the process of littoral drift, sediments from the watershed caused a great increase in sand supply to the dune system. In the 1920s, Highway 1 was inundated with sand and had to be realigned. By the 1950s the dunes were in a relatively stable condition. Off-road vehicles gradually became popular, however, and by the 1970s a great deal of off-road vehicle use and renewed dune movement was evident. Numerous riparian swales were inundated. In some cases the willows were able to grow faster than they were being covered with were being covered with sand, eventually ending up on dune crests and helping halt the inward movement of sand (fig. 8). DPR is currently conducting studies of the impact of off-road vehicles on the dune system and methods to restore the fragile dune vegetation. Of special interest is the unique riparian ecosystem adjacent to Sand Hill Lake. This fen-carr ecosystem is the only one of its kind known in California (Barry and Schlinger 1977).

The most critical off-road vehicular impacts occur at Pismo Dunes State Vehicular Recreation Area, San Luis Obispo County. Here, extremely heavy use has destroyed hundreds of acres of dune vegetation.

Figure 8.

Willow riparian area being inundated by active

dunes, Ten-Mile Dunes, MacKerricher State Park.

As a result, most swale riparian ecosystems have been covered up within the first 1.6 to 2.4 km. (1 to 1.5 mi.) of the beach. Oso Flaco Lake, which is surrounded by riparian vegetation and numerous rare endemic, endangered, or otherwise threatened species, is slowly being inundated with sand. A massive dune revegetation program has just been initiated to the windward side of the lake. Revegetation is to be with native dune vegetation; seed collections and cutting stock are being taken from within the dune system. Remaining examples of dune plant communities are being described, mapped, and analyzed through a series of permanent plots. Fencing will be installed to keep vehicles out of the windward dunes. Although DPR plans to spend $160,000 per year on this restoration project, it may be too late to save this unique dune lakes area, which separates the dune system from the rich agricultural lands to the east.

On-Site Impacts

On-site impacts to riparian ecosystems encountered in the State Park System include livestock grazing, cultivation, exotic species invasion, off-road vehicle damage, equestrian trampling, and human trampling, roughly in that order of importance.

With the recent passage of SB 2469,[11] the otherwise inviolate natural resource of the State Park System[12] now may be leased for agriculture purposes. It has long been known that cultivation, grazing, and the interruption of natural flooding and fire cycles have threatened the existence of the magnificent valley oak savannas, woodlands, and forests of California.

[11] Section 5069 PRC.

[12] Section 5001.65 PRC.

More subtle but just as critical is the impact of grazing on the understory of riparian communities. Native grasses and palatable native forbs are eliminated and replaced by thistles and other alien weedy species. A once very widespread riparian native understory grass, blue wildrye (Elymusglaucus ), has all but been eliminated from these ecosystems. Relict stands of blue wildrye occur associated with valley oak and cottonwood communities on the floor of Yosemite Valley (Tuolumne and Mariposa Counties), in Hungry Valley State Vehicular Recreation Area (Ventura County), and Malibu Creek State Park (Los Angeles County). Grazing of riparian ecosystems also affects the water quality of adjacent waterways. Ahjumawi Lava Springs State Park (Shasta County), illustrates this problem. The springs, rivers, ponds, and lakes in and adjacent to this unit show phosphorus and nitrate loading, with algae blooms turning much of the water green. Cattle roam freely in and out of the aquatic wetland and terrestrial ecosystems of the unit (fig. 9).

Figure 9.

Cattle grazing in the riparian zone at Ahjumawi Lava Springs State Park. Domestic

grazing animals have become a serious ecosystem management problem.

The invasion of alien species is almost universal in riparian ecosystems. Alien species from the Mediterranean region are common in the understories of riparian communities throughout the state. Blue gum (Eucalyptusglobulus ) and other Eucalyptus species have displaced native riparian vegetation at Mt. Tamalpais (Marin County), Montana de Oro (San Luis Obispo County), and Annadel (Sonoma County) state parks. When resource management programs are planned or initiated to eliminate these alien, low-diversity communities and replace them with native riparian species, considerable local opposition has usually all but stopped the efforts.

At Point Mugu State Park, a prime example of a California sycamore riparian woodland ecosystem occurs (fig. 10). However, over 100 years of grazing has eliminated of most native herbs in the understory. The understory is made up largely of milk thistle (Silybummarianum ), an alien species which needs disturbance of the soil surface for germination and soil compaction to compete with native species; both factors are provided by the hooves of domestic livestock. To date, a control method for milk thistle has not been found, but biological control methods are being investigated.

In Anza-Borrego Desert State Park many native riparian ecosystems are being invaded by salt cedar (Tamarix gallica ), an alien species of Euroasia which not only is out-competing native riparian species, but is also causing springs which the desert big horn sheep and other wildlife rely on for summer and fall water supply to dry up. The problem concerns the California Department of Fish and Game (DFG) as well as DPR. To date, no method has been found to eradicate salt cedar. The problem has been investigated by the National Park Service (NPS) with no satisfactory results. The answer will likely be found in the natural habitat of salt cedar. Somewhere in Eurasia a biological control may exist.

Figure 10.

California sycamore riparian woodland in Point Mugu State Park being grazed.

Most native understory herbs have been replaced by alien weeds.

The off- and on-site impacts of off-road vehicles at Pismo State Vehicular Recreation area have been covered. Severe on-site impacts due to off-road vehicles are well illustrated at Hungry Valley State Vehicular Recreation Area (fig. 11), Anza-Borrego Desert State Park, and Red Rock Canyon State Park (Kern County).

Figure 11.

Sedimentation in riparian woodland, Canada de Los Alamos,

Hungry Valley State Vehicular Recreation Area. Off-road

vehicle use upstream is causing siltation.

Only Hungry Valley State Vehicular Recreation Area will be covered here. The understory of a Fremont cottonwood riparian forest has been about 90% destroyed in the informal staging and camping area at the northern end of the unit (fig. 12). Unique valley oak woodland and savanna ecosystems are threatened with similar devastation. The understory of the valley oak woodland here contains more native grass species than known from any other area in the state. Here blue wildrye (Elymusglaucus ), deer grass (Muhlenbergiarigins ), purple needle grass (Stipapulchra ), nodding needlegrass (Stipacernua ), and giant squirreltail grass (Sitanionjubatum ) occur along with willows (Salix sp.) and California wild rose (Rosa californica ).

This unique riparian ecosystem, along with the largest and most diverse native grassland ecosystem within the foothills region of the state, was proposed for natural preserve status at the October 1981 State Park and Recreation Commission hearing in Los Angeles. The proposed natural preserve status for the small valley oak woodland has not been opposed by the off-road vehicle special interest group. However, the proposed natural preserve status for a larger, 567-ha. (1,400-ac.) native grassland has met strong opposition; the grassland is likely doomed to offroad vehicular use and ultimate destruction.

Figure 12.

Off-road vehicular staging area has caused destruction of understory and groundcover in

Fremont cottonwood riparian woodland, Hungry Valley State Vehicular Recreation Area.

Conclusions and Recommendations

Resource management objectives in riparian ecosystems of the State Park System are focused around alleviating a number of long-term problems, some of which may have no satisfactory solutions. Others have expensive long-term solutions.

Wise and sensitive planning is necessary to ensure the perpetuation of high-quality riparian ecosystems. A long-term ecological monitoring program with good baseline data (permanent plots, transects, etc.) is needed to adequately manage riparian ecosystems.

Special interest legislation which allows grazing, logging, mining, commercial fishing, hunting, etc., within the State Park System is, and will remain, a serious problem. Such legislation circumvents the objectives of the State Park System. Perhaps a constitutional amendment, to the effect that the State Park System and the DFG Ecological Reserve System are inviolate and must not be commercially exploited, is necessary.

Literature Cited

Barry, W.J. 1979. Proposed natural heritage program for California, partial draft. 113 p. California Department of Parks and Recreation, Sacramento.

Barry, W.J. and E.I. Schlinger (ed.). 1977. Inglenook Fen, a study and plan. 212 p. California Department of Parks and Recreation, Sacramento.

Cleveland, G.B. 1973. Fire + rain = mudflows, Big Sur, 1972. California Geology 26(6):127–135.

Mason, H.L. 1970. The scenic, scientific, and educational values of the natural landscape of California. 36 p. California Department of Parks and Recreation, Sacramento.

Michaely, R.D., J. Cochran, J. Barry, and R. Batha. 1976. Salt Point State Park resource management plan and general development plan. 55 p. California Department of Parks and Recreation, Sacramento.

Troy, R.E., R.D. Treece, and H.F. Hallett, Jr. 1980. California State Park System Plan 1980, an element of the California outdoor recreation plan. 239 p. California Department of Parks and Recreation, Sacramento.

Planning Recreation Development and Wildlife Enhancement in a Riparian Environment at Orestimba Creek[1]

Robert H. Morris[2]

Abstract.—This paper summarizes the proposed project for wildlife enhancement and recreation development at Orestimba Creek (Stanislaus County) and discusses problems involved. Some of the problems are especially important because they are common in other riparian environments where public recreation is proposed. This paper deals more with questions than answers. However, an examination of problems is an important phase of productive management of riparian systems.

Introduction

The proposed recreational development and wildlife enhancement project at Orestimba Creek is a reflection of the concern the California Department of Water Resources (DWR) has for restoration and management of our remaining riparian resources. It is justified by the DWR's legal requirement to include planning for recreation and wildlife habitat enhancement in all appropriate activities involving construction and operation of the State Water Project. The remnant riparian environment at Orestimba Creek, located adjacent to the California Aqueduct, makes it an ideal site for such planning.

This paper is based on a critical examination of some of the problems involved in the project. This does not mean the writer is not in favor of the proposal. On the contrary, the proposed plan could be an effective method of conserving and managing the remaining riparian resources at the creek—if development and operation are carefully implemented. The critical approach is taken to emphasize problems that are pertinent to management of California's riparian systems.

Description of the Site

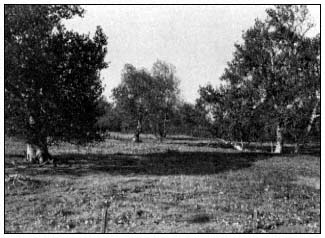

Orestimba Creek is an intermittent stream which flows eastward into the San Joaquin River, draining the Diablo Range of the Coast Ranges. In an average year, flow in the creek occurs only during the winter and spring, mostly from January through April. Except for runoff from adjacent irrigated orchards, the creek is dry for the rest of the year. However, the presence of large sycamores (Platanusracemosa ) (fig. 1) attests to the perennial presence of abundant near-surface water.

The project site is located on a 2.4-km. (1.5-mi.) length of the creek in the western part of the San Joaquin Valley in Stanislaus County. The upstream and downstream limits of the site are defined by the California Aqueduct and the Delta-Mendota Canal, respectively. Both the aqueduct and the canal are siphoned under the bed of the creek to allow the stream to maintain its natural flow. Interstate 5 crosses the creek about 0.8 km. (0.5 mi.) upstream from the Delta-Mendota siphon.

A marshy basin with excellent potential for enhancement as wildlife habitat has formed at the downstream end of the project. Many kinds of wildlife are present throughout the year, both along the creek and in the marsh. Some of these are deer, rabbits, squirrels, ducks, pheasants, herons, quail, doves, and a large variety of smaller birds. Indian Rocks is an additional important amenity. It is a sedimentary outcrop located less than 0.8 km. (0.5 mi.) south of the upstream end of the project area (fig. 2). The site has historical value as a wayside camping area used by early Indian tribes in the valley (Napton 1980).

The part of Orestimba Creek involved in this project is an excellent example of one of California's remnant riparian environments. In addition to a lush growth of other riparian plant species, there are over 300 native sycamores clustered within the limits of the site (fig. 1). These

[1] Paper presented at the California Riparian Systems Conference. [University of California, Davis, September 17–19, 1981].

[2] Robert H. Morris is Recreation Planner, California Department of Water Resources, Sacramento.

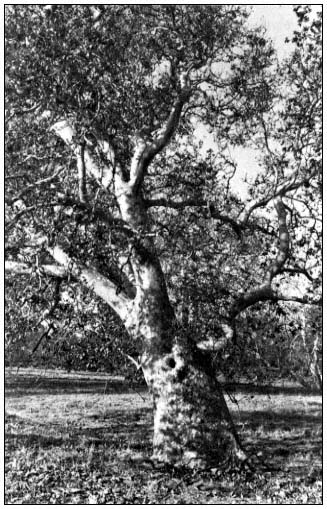

Figure l.

Large California sycamore on the floodplain of

Orestimba Creek. (Photograph by R.E. Warner.)

are among the finest specimens of the species remaining in the San Joaquin Valley. Surrounded by orchards, plowed fields, angular water canals, and concrete traffic lanes, the site stands out like an oasis from the past, a remnant of another time. Although the valley surrounding it has changed, the appearance of this short length of creekbed with its sycamores (many dating back hundreds of years) is quite similar to that when the Miume Yokuts used it as a wayside resting area that provided shade and relief from the scorching summer heat of the valley. The principal difference today is the lack of ground- and shrubcover, and the absence of young trees, because of long-term cattle grazing in the riparian zone (fig. 3).

The riparian site at Orestimba Creek with its magnificent sycamores has excellent potential for recreation development and wildlife enhancement. The 2.4-km length of creek has gently sloping banks that are ideal for installing recreation facilities with minimum disturbance to existing topography. Indian Rocks at the upstream end of the site is within easy hiking distance of the creek. An intensive investigation by the Institute of Archeological Research, California State College, Stanislaus, indicated these attractive geological features have good potential for development as an outdoor museum displaying the important historical and archeological significance of the area. The marshy basin at the downstream end of the project area has fine potential for enhancement as wildlife habitat. This could include a program for public observation and nature study. The adjacent bikeway along the California Aqueduct would provide easy access to and from the creek. No other location along the 113-km. (70-mi.) length of bikeway provides access to a creekside environment like the one at Orestimba Creek. Finally, Interstate 5 and other existing roads provide excellent access for public recreation use.

Project Summary

Proposals for development and enhancement at Orestimba Creek fully utilize the excellent potentials that exist there. Perhaps the most important aspect of the plan is the conversion of the existing intermittent creek into a stream with year-round flow. This would be accomplished by gravity releases of water into the creek from the California Aqueduct at the upstream end of the site. The releases would be made during summer months when the creek is normally dry. They would be carefully planned and controlled to enhance the 2.4-km. downstream site for both recreation and wildlife without causing erosion or other problems. The amount of water released would be determined by the flow required to flush and maintain adequate water quality in a swimming pond to be excavated in the creekbed. The flow would also link a chain of fishing ponds created along the stream by carefully deepening and widening the existing channel at appropriate locations. Excess water would pond in the marshy basin at the downstream end of the site.

On a long-term basis, the summer water releases would modify the existing riparian environment. Some of these changes would be beneficial, but others may be less desirable. Because of this, an important part of the proposed project is a management plan to control and direct changes that would occur. A major concept of operation and management at the site is to limit recreational use to a level that would assure long-term conservation of this remnant riparian environment. Entry control, limitation of parking and other facilities, and appropriate supervision of on-site activities are three important parts of productive management that would assure conservation.

Both the creekbed and the marsh would be modified to improve habitat for a year-round fishery. In addition to deepening and widening exist-

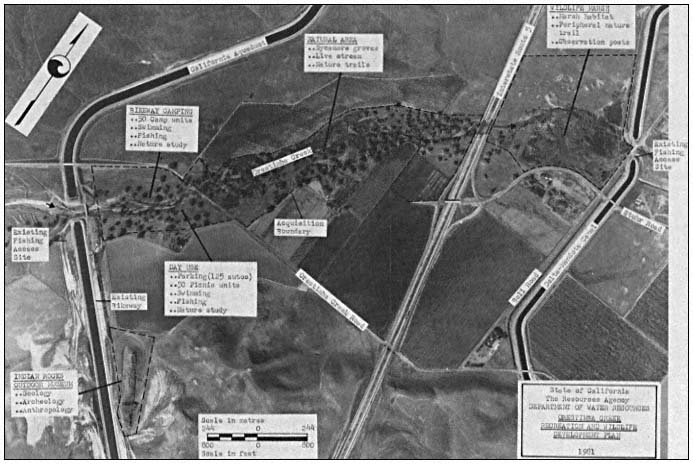

Figure 2.

Orestimba Creek recreation and wildlife development plan.

Figure 3.

California sycamores on Orestimba Creek floodplain. Note

absence of ground-and shrubcover and sycamore reproduction

due to cattle grazing. (Photograph by R.E. Warner.)

ing pools, this modification would include a carefully managed planting program to establish new plant species that would provide shade and escape cover beneficial to fish reproduction. The planting program would also add new species to provide additional food and cover for wildlife. Planners hope this will attract new animals which have a greater tolerance for coexistence with people to the site, to replace those species that leave when initial development and public recreation use begins.

In conjunction with the year-round stream concept, the following facilities are proposed as part of the plan for Orestimba Creek (see fig. 2 for specific locations).

A day-use area would be carefully constructed under the canopy of an existing sycamore grove. The area would provide access to an instream swimming pond, a picnic area, the chain of fishing pools along the creek, and a streamside hiking trail linking the upstream and downstream ends of the site.

A small wayside camping area for cyclists using the California Aqueduct Bikeway would be located adjacent to the day-use area, but on the opposite side of the creek. The two areas would share basic facilities and be linked by a pedestrian bridge across the creek.

An outdoor museum is proposed at the Indian Rocks site to display for public viewing the historical and archeological significance of the area. The museum would emphasize the area's importance as a campsite of early nomadic Indian tribes of San Joaquin Valley. An appropriate access trail would be provided.

A shoreline interpretive trail would be constructed around the periphery of the downstream marsh, with observation posts to point out important natural features. This interpretive trail would be linked to the creekside hiking trail extending the length of the site.

The remainder of the riparian environment within the project area, including most of the existing sycamores, would remain in its present undisturbed condition. The plan would not deplete or infringe upon agricutural production in the surrounding area. The only land taken for recreation development and wildlife enhancement would be the rocky bed of the creek, the marshy downstream basin, and the outcrop at Indian Rocks. The project could result in a net increase in productive land if the State can trade its adjacent landholdings with agricultural potential for some of the property required to implement the plan.

Is Public or Private Ownership Best?

Anyone with a sincere concern for future conservation of the riparian environment at Orestimba Creek must consider the relative merits of public and private ownership. Is it in the best long-term interests of the site to remove it from private ownership? Will government ownership proposing public use and more productive management provide better assurances for future preservation? To answer these questions, the nature of existing private ownership must be considered.

Three landowners are involved. The first is a local family whose ancestors came to the valley as pioneers many years ago. The family has strong ties to the land and a sincere interest in retaining ownership and preserving the site. They have owned their part of the creekbed for as long as anyone can remember, and they maintain a "barbwire" stewardship that has effectively protected the remnant riparian land by excluding all public access. Although there has been no "productive management" to enhance the creekbed, there can be no doubt that many of the sycamores and much of the other riparian vegetation has survived only because of the protection provided by this private ownership. The family is against any proposal to take the land for public use.

The second landowner does not date back to pioneer days, but he also has held his land at the creek for many years. His interests are more commercially oriented. He owns and manages extensive orchard developments along the north and south sides of the creekbed. To protect his orchards, this owner practices the same land stewardship that excludes all public access. Although his motives are different, the results have been the same. The riparian system has survived because of the effective protection provided by the existing private ownership. This landowner is also against the plan to take his holdings at the creek for public use, even though none of his orchard property would be involved.

The third owner is very different. It is a nonresident corporation; the property along the creek is a recent acquisition. The corporation proposes major new commercial developments that include facilities for travelers using Interstate 5. If these plans are implemented, they will attract large numbers of people to the area adjacent to the creek. The corporation is in favor of the plan to open the site for public recreation, primarily because the owners believe it will positively affect their proposed developments. They are willing to sell their part of the creekbed needed by the State if they can benefit by the sale. They do not believe their proposed traveler facilities will have any adverse effects on survival of the adjacent riparian environment of Orestimba Creek.

Approximately 80% of all riparian systems in our country are presently in private ownership and have not been subjected to governmental management (Warner 1979). The remnant site at Orestimba Creek is part of this 80%. Although the land surrounding it has been changed substantially for agricultural uses, the creekbed has remained relatively unchanged. It has survived primarily because of its lack of value for development and the exclusion of the public by private owners. In consideration of this, is it in the long-term interest of the site to substitute governmental management which proposes public use?

New corporate ownership at the creek proposes changes that may threaten the survival of the adjacent riparian system. On the other hand, the limited funds available may not assure appropriate governmental operation to control public uses. We are all familiar with the damage that an unsupervised public can inflict on a fragile riparian environment like the one at Orestimba Creek. Public ownership may be the best way to go, but only if governmental management can assure that this remnant site has at least as much protection in the future as it has had in the past under private stewardship.

Are Public Recreation and Wildlife Preservation Compatible?

Riparian systems are as attractive and useful to people as they are to dependent fish and

wildlife populations (ibid .). This is surely true for the section of Orestimba Creek involved in the proposed plan. As indicated, the site is located adjacent to the California Aqueduct and has excellent potentials for both recreation development and wildlife enhancement. However, the question of compatibility must be considered. Is it logical to assume that these two uses can occur simultaneously at a small, fragile site such as Orestimba Creek?

Remnant riparian environments often constitute the only available roosting, nesting, and escape habitat for many wildlife species (ibid .). This is undoubtedly the case at Orestimba Creek. As the surrounding valley has been modified for agricultural production, the creek and adjacent riparian system have become an escape site for many indigenous species that at one time were present in much greater numbers. Most (if not all) of these remaining animals have definite territorial needs that must be met. In consideration of this, is it good planning to infringe on this remaining sanctuary by trying to combine public recreation use and wildlife enhancement at the same small location?

The summer water releases from the Aqueduct will significantly improve the riparian environment along the creek and in the downstream marsh. This, in conjunction with the planting program to provide additional food and cover resources, should attract new species to the site. However, is it reasonable from a biological point of view to assume most of these animals will be able to adjust their territorial needs to coexist with people in a public recreation setting? At a larger site with adequate room for separation and buffers, the two conflicting uses could probably be managed effectively. Space restrictions at Orestimba Creek may be the limiting factor that will preclude long-term survival for many of the remaining wildlife species in the presence of recreational development.

If the proposed plan, including effective management and operation, is carefully implemented, the creek site can be enhanced for both recreation and wildlife. Limiting public use and maintaining on-site control are two important parts of effective operation. They are necessary if the riparian system is to remain a viable environment for most species. Changes will inevitably occur—to the detriment of some species and the advantage of others—but long-term preservation can be reasonably assured. This preservation will probably involve compromises for recreation and/or wildlife.

Does Existing Environmental Law Provide Adequate Protection?

It is probably safe to assume that most people involved with the issue generally agree that existing environmental laws (National Environmental Policy Act and California Environmental Quality Act) provide important protections for the conservation and management of our remaining riparian systems. The environmental investigation and analysis required under these laws assure consideration of significant impacts and long-term preservation. This is especially important because in America over the last 150 years, between 70% and 90% of indigenous riparian resources have been destroyed (ibid .). Adequate legal protections must be provided if the remaining riparian environment is to survive. However, if we take a closer look at specific ways in which environmental laws are interpreted and applied, some serious doubts arise concerning their adequacy. The project described in this paper provides one example of contradictions that can occur.

The plan to develop recreation and enhance wildlife at Orestimba Creek requires completion of a full environmental impact report (EIR) before any final decision for the project can be made. The EIR must evaluate all significant impacts of the proposal and consider mitigation measures and alternatives to the project to minimize adverse impacts. A draft of the report must be available for review by all interested parties, and comments received from reviewers must be given adequate consideration. These are all requirements under the California Environmental Quality Act, and they provide important protections for the remnant riparian site at the creek. This is an example of an appropriate application of the law.

Another recent activity at the Orestimba Creek site presents a different interpretation of the law. A gravel extraction operation just a few hundred feet upstream from the proposed project has been in process for some time and has already produced significant adverse impacts. A large area of the creekbed has been graded clean to excavate gravel material. This has removed protective vegetative cover important in reducing erosion damage during winter floodflows. In addition, a temporary road was constructed across the creek to provide access for gravel trucks. The loose material used to construct the crossing will produce a substantial increase in downstream siltation during winter flows. If the gravel operation continues, it will create serious erosion and siltation problems for downstream recreation use and wildlife enhancement. Even without the proposed project, gravel removal will adversely affect the existing downstream riparian site.

Considering these obvious impacts that surely could have been predicted, why and by what authority was this type of commercial activity permitted? In apparent compliance with the provisions of the California Environmental Quality Act, Stanislaus County officials reviewed the project and granted it full environmental clearance under a Negative Declaration that states the activity will not have significant effect on the environment at the creek. Mitigation measures were not made a condition of the approval, and apparently the extraction operation will be permitted to continue as long as it is economically feasible.

This contradictory application of environmental law raises doubts about is efficacy for preserving at least some of our remaining riparian resources. Based on individual interpretation, the legal "protection" represents a two-edged sword. Those of us concerned with preserving what we have left must be vigilant in our efforts to assure that the cut is for, not against, our cause.

Who Will Pay for Conserving and Managing Our Remaining Riparian Resources?

The Orestimba Creek project involves another problem pertinent to management of riparian systems. The proposed site has excellent potentials for recreation use and wildlife enhancement. It is equally important that the remaining riparian system be conserved and managed effectively, but who will assume responsibility for doing the work and where will the required funds come from? Despite its excellent potentials, there is significant doubt that a capable operator with adequate funds will be found to develop and operate the proposed creekside site.

Conservation and productive management of our remaining riparian resources must involve a coordinated multi-agency approach that includes federal, state, county, municipal, and private owner stewardship (ibid .). This is the most effective approach to the problem. However, considering the financial bind that governmental and private agencies are facing (with the compounding effects of rising costs and declining revenues), is it reasonable to expect that large sums of money will be available to do the work required? With the recent cutbacks in many vital services, is it logical that governmental agencies at any level will give a riparian resources program high priority when allocating limited funds? If government participation will be difficult to obtain, is it any more reasonable to expect private ownership, faced with the same revenue and inflationary problems, to invest large sums of money in conserving and managing riparian land when there will be no dollar profit obtained from the investment?

Answers to these questions must be realistically considered before we begin to develop a program to preserve our remaining riparian resources. No matter how valid our motivations, our programs will be meaningless if adequate funding is not available for implementation. This is true for the Orestimba Creek project specifically and other proposals to preserve riparian systems in general.

Literature Cited

Napton, L. K. 1980. Cultural investigations of the proposed Orestimba Creek wayside park, Stanislaus County, California. 142 p. California State College, Stanislaus, Institute of Archeological Research, Department of Anthropology, Turlock, Calif.

Warner, R.E. 1979. The California riparian study program. 177 p. Planning Branch, California Department of Fish and Game, Sacramento.

Management of Cultural Resources in Riparian Systems[1]

Patricia Mikkelsen and Greg White[2]

Abstract.—Prehistoric inhabitants of California's North Coast Ranges utilized riparian systems in patterns reflecting cultural and natural environments. Archaeological investigations seek to define these prehistoric cultures and paleo-environments and preserve their remains. The status of archaeology under federal and state legislation can help preserve and protect both cultural and natural resources.

Introduction

Cultural resources are broadly defined as "districts, sites, buildings, structures, and objects, significant in American history, architecture, archaeology, and culture."[3] They are important non-renewable features of scientific, social, and historic value that often occur within riparian systems. Prehistoric archaeological sites are among the cultural resources found there and are the primary concern of this paper.

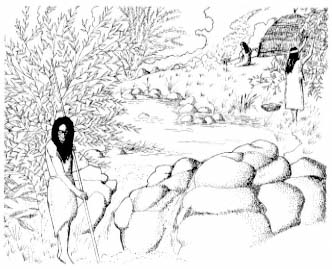

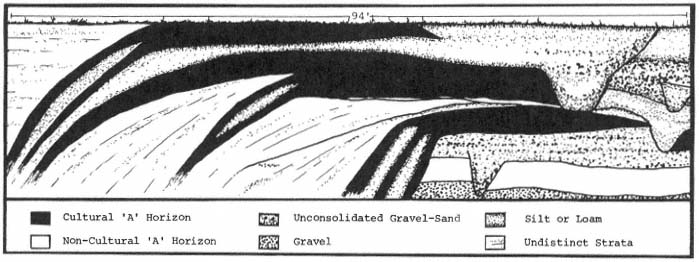

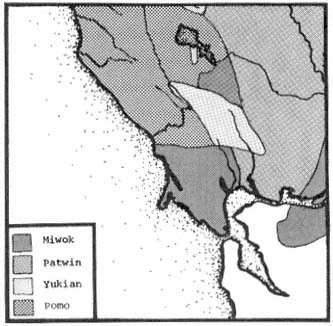

An archaeological site (the location of past cultural activities) contains evidence of adaptation to a local environment. Archaeological data in California, along with ethnographic information (gathered from living people), have revealed complex native American cultures with settlement patterns and land-use practices that gave an integral role to the abundant riparian vegetation, wildlife, and water supplies (fig. 1). From this perspective, studies of the component aquatic and riparian systems comprising these ecosystems are important for archaeological interpretation, as native Americans were an integral part of such systems.

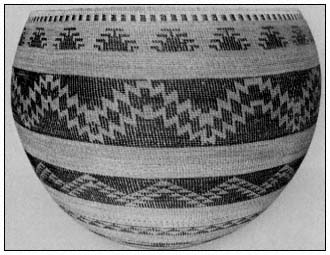

Figure 1.

Native American activities in a riparian system.