PART TWO—

NUMINOUS MATES

Social hierarchy was being redefined in America when Nathaniel and Sophia were growing up: middle-class hegemony displaced the seaboard landholding gentry that had provided leadership in the Revolution and in the writing of the Constitution, and this shift brought about a transformation in the status system of American society. A new elite emerged as the old elite declined; what changed, however, was not merely the membership of a fixed upper class but the terms on which elite status could be claimed. Individual achievement supplanted family heritage as the keynote of social worth.[1]

In "The American Scholar" (1837) Ralph Waldo Emerson noted "the new importance given to the single person" (Whicher, 79) as a pre-eminent sign of the times and sought to provide a spiritual underpinning for the emerging ideal of individual autonomy. The story of self-reliant struggle from humble origins to high position became the ruling narrative of manly worth, supplanting that of the well-born lad demonstrating his superior breeding in the exercise of responsibilities that were his birthright. The ideal of the youthful aristocrat enacted by Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson gave way to that of the self-made man. This new model of manly worth was a creation of a bourgeois culture that sought to reconcile the egalitarianism of Revolutionary ideology with continuing social stratification, holding that men are equal at birth and that just inequalities develop as differences of talent and virtue reveal themselves in democratic competition.

Families, especially prominent, powerful families, have been considered sacred from the origins of Western civilization. In early nineteenth-century America, however, the family became a focal point of religious reality in a new way. Social faith in the differential sacredness of bloodlines gave way to a numinous authority newly invested in the domestic circle, with the nurturing presence of the middle-class wife and mother at the center of the sacred tableau.

Lineage through the male line certainly did not cease to count as a marker of identity and an indicator of status in nineteenth-century America, and marriages continued to be made so as to strengthen and perpetuate family wealth and position. Yet it became proverbial by mid-century that a young man could be crippled by distinguished origins, what Nathaniel Hawthorne called inheriting "a great misfortune" (CE 2:20).[2] As the culture of commercial capitalism became established, social arrangements arose to accommodate the "perennial gale of creative destruction" that Joseph Schumpeter marked as its central quality (84). With all fortunes now apparently at risk, the men who emerged winners in the competitive new society gave credit to

wives who had assisted them by providing a space of retreat from the struggle and the vision of a loftier humanity that ennobled their financial success. The self-made man had his cultural counterpart in the domestic angel, the woman with whom he had formed a marriage based not on inherited property but on mutual affection and moral fitness.

These social issues are easily recognizable in the broad thematic structure of The House of the Seven Gables: the family as lineage is desacralized in the fall of the Pyncheons, and the emerging ideal of domesticity is celebrated in the relation of Holgrave and Phoebe. But the imaginative design of Hawthorne's novel is composed of elements through which Nathaniel and Sophia sought to make sense of themselves. If they had never met one another, they would nonetheless have formed narratives of their personal experience that deployed the emerging conceptions of family and gender and would have spelled out in their lives the warfare of meanings that characterized the social transformation then taking place. The middle-class home did not smoothly replace the dynastic household as a cultural ideal. As typical figures of the "new" arrangement, Nathaniel and Sophia were caught in the struggle to distinguish it from an "old" pattern that still entered strongly into their self-understanding.

Nathaniel and Sophia had already imagined one another before they met; on meeting, they found that their two narratives were already one. They lived out an ideal that asserted not merely "natural" manhood and "natural" womanhood coming into accord, but the perfection of an "individual" accord: their two stories appeared to be written for each other, the marriage made in heaven. This myth of a uniquely preordained interlocking of individual selves lay at the heart of the claim to elite status that such marriages embodied.

As their lives articulated social circumstance, so the Hawthornes became its local exemplars; and for a much larger public The House of the Seven Gables enacts a comparable drama, in which a cultural order is fashioned that both nourishes and consumes its offspring. The story of the Hawthornes as numinous mates does not offer a "source" of The House of the Seven Gables, as though it were raw material that was submitted to the transforming alembic of Hawthorne's creative imagination. Like the selfhoods that Nathaniel and Sophia brought to it, the relationship between them was an imaginative achievement in an especially strong sense.

When Sophia's older sister referred to their marriage as "the coming together of two self-sufficing worlds" (Pearson, 276), she meant more than a late marriage between persons who had become accustomed to living

single. Both Nathaniel and Sophia projected a distinctive aura; neither was an easygoing person, smoothly accommodating the peculiarities of others. Julian Hawthorne frequently refers to the "enchanted circle" (NHW 1:48) his mother cast about her; and evidences are plentiful that Hawthorne projected a momentous "presence."

What is the relation between the spell cast by a work of literature and such personal charisma? How is the collective life of art related to the psychic energy that radiates from a man or woman so strongly as to compel the imagination? Is so urgent an aura the sign of social conflict within the self? Does an individual become a "self-sufficing world" because he or she has internalized unstable and shifting identities, so that the working coherence necessary to sanity becomes precarious? How do two such coherencies become one, as the imaginations of Nathaniel and Sophia postulate and then discover one another? And how do we ourselves, with our workaday selfhoods, find not only that we have imagined Hawthorne's writings before we read them but also that the shamanistic force contemporaries encountered when they dealt with him, or with Sophia, still reaches us?

Chapter Three—

The Queen of All She Surveys

Sophia Hawthorne is the most vilified wife in American literary history, after having been in her own time the most admired. Elizabeth Shaw Melville has been blamed for not having measured up to Fayaway, and although Lidian Emerson was eminently presentable, like her short-lived predecessor, Ellen Louisa Tucker, neither woman is credited with having a vital relation to her husband's imagination. Thoreau, Whitman, and James did not marry, and Henry Adams's wife, Clover Hooper, is omitted—a gasping silence—from the story of his education. Sophia Hawthorne, by contrast, was hailed as indispensable to the flowering of her husband's genius, a role that Hawthorne himself fervently celebrated and impressed upon his friends and his children. "Nothing seems less likely," Julian affirmed, "than that he would have accomplished his work in literature independently of her sympathy and companionship" (NHW 1:39).

Scholars in our own time have found Sophia a force to be reckoned with. When Randall Stewart discovered how extensively she had edited the English Notebooks, he noted "the Victorian ideal of decorum" that guided her and concluded that her interferences cannot fairly be judged against twentieth-century standards of editorial scholarship (English, xxi). Yet compared with Nathaniel's genius for undermining the decorums of Victorian life, Sophia's temperament seems an epitome of moralistic hypocrisy. Frederick Crews has noted the zealous minute care with which her revisions purify

Hawthorne's language, observing that many of her alterations draw attention to indecent meanings that would pass unnoticed if she had not marked them. Crews condemns this as "the work of a dirty mind" (12–14). Not only is Sophia peculiarly alert to what she considers nasty, but the whole course of her censoring impulse runs counter to the openness of Hawthorne's imagination. It has become hard to understand how the man who wrote Hawthorne's works could have married Sophia at all, to say nothing of pronouncing her an indispensable source of spiritual sympathy and support.

The commonly accepted picture of Sophia conceals her playful warmth, her intellectual fervor, and the fierce independence of her spirit. Sophia was a maker of manners; and she continues to stir involuntary loathing because she remains a powerful avatar of a perishing god. (It is not hard to show disinterested curiosity in a divinity one has never worshiped, by whose adherents one has never been injured or aided.) The domestic angel had a primal religious force in the nineteenth century that she no longer enjoys, yet something of the awesome old energy still haunts us.

The growing sadness of Sophia's life, like the growing shrillness of her moralism, results in good measure from a paradox at the heart of her achievement. She pioneered a convention of womanhood that obliged her to deploy her creative powers vicariously, through Nathaniel. Among women who have sought to fulfill themselves through the achievements of a man, few have succeeded better than Sophia. She chose a man bound for greatness, in whom her own ambitions could be realized and to whom she was truly indispensable. The ironies of that triumph and its fearful price will occupy us to the end of her story; and they are already evident at the outset, where the inner meanings of her illness took form.

The "female malady" that harassed and interrupted the lives of other Victorian women became for Sophia an embracing idiom of selfhood.[1] Her primary symptom was a disabling headache typically tripped off by unexpected noises, at times so slight as the clinking of silverware. Sophia found a spiritual portent in these agonizing experiences and persistently sought their meaning.

All day yesterday my head raged, and I sat a passive subject for the various corkscrews, borers, pincers, daggers, squibs and bombs to effect their will upon it. Always I occupy myself with trying to penetrate the mystery of pain. Sceptics surely cannot disbelieve in one thing invisible, and that is Pain . Towards night my head was relieved, and I seemed let down from a weary height full of points into a quiet green valley, upon velvet turf. It was as if I had fought a fight all day and got through.[2]

A mythological haziness surrounds accounts of the onset of Sophia's problem, in which one nonetheless finds clear assertions of her having been remarkably vigorous and healthy in girlhood (Cuba, xxx; Tharp, 24). At the age of twenty-four Sophia spent a year in Cuba, hoping that relaxation and the warm climate would cure her; she wrote home that "it would be utter folly to expect a rooted pain of fifteen years or more to be expelled in 'one little month'" (Cuba, 25). Taken as a key to chronology, this remark would indicate that the illness began when Sophia was nine years old or younger; but we are not dealing here with chronological time. This "rooted pain" was deep in the self and thus is felt to be deep in the past. Julian traces the trouble even closer to the sources of Sophia's identity; his version of the family story blames her dentist father, who "incontinently" dosed her with allopathic drugs when she was teething (NHW 1:47).

Louise Tharp's Peabody Sisters of Salem sketches a still earlier myth of origins that suggests why it seemed plausible to blame her father's ineptitude. At the heart of Sophia's illness was an anti-patriarchal impulse that is visible in the tradition of womanly character from which she sprang.

The Peabody family was among the most distinguished in New England during Sophia's girlhood; but the Palmers—her mother's family—figured largest in the claim to high status that the women of the family asserted. Sophia's mother—Elizabeth Palmer Peabody—retained worshipful memories of a grandfather, General Palmer, who was a pre-Revolutionary aristocrat. He made his home at Friendship Hall, a splendid mansion set in the midst of extensive landholdings, where Elizabeth in childhood stretched out on the floor of the library to read Shakespeare and Spenser from leather-bound volumes.

Sophia's crisis of health at her entry into adulthood replays that of General Palmer's daughter Mary.[3] She too possessed unusual physical vigor and was a crack shot and a fearless rider. So intrepid was she, in fact, that her father consented to a test of nerve proposed by her fiancé, who crept up on her while she was reading in the garden and fired a pistol close by her head. Mary Palmer forthwith went into hysterics, broke the engagement, and secluded herself in her bedroom as a nervous invalid unable to endure sudden noises.

Alexis de Tocqueville observed that the transition from girlhood to womanhood in democratic America was a drastic change, and while he tried to put an attractive face on it, his description makes clear it was a change for the worse. "The independence of woman is irrecoverably lost in the bonds

of matrimony." She leaves her father's house, an "abode of freedom and of pleasure," to live "in the home of her husband as if it were a cloister" (2:201). This typical crisis may have become more pronounced in the 1830s, when Tocqueville came to America, than it was when young Miss Palmer took to her bed fifty years earlier. Yet the plight of a strong-minded young woman facing the limitations of marriage is a time-honored theme of family relations. It is a staple of Shakespeare's plays—as with Hermia, Portia, Juliet, and Cordelia—where the father's tyrannical command brings on the conflict.

The "joke" played on General Palmer's spirited daughter was a joint enterprise, carried out together by the two men, and it seems evident that her nervous ailment was a protest against the servitude that the gunshot announced, matrimony as a state of subjection to her husband, fully authorized by her father. General Palmer, it seems, yielded to his daughter's protest: he was stricken with remorse and gave orders that members of the household observe silence within earshot of her bedroom.

The rebellious spirit that goes into such a protest strongly characterized Sophia Peabody's foremothers. Her grandmother Betsey Hunt—also brought up in luxury—secretly taught herself to read because her father forbade instruction; and she eloped with young Joseph Palmer, the general's son, who had been willing to supply her with books.

Elizabeth Palmer Peabody, Sophia's mother, inherited a full share of this womanly valor; she struggled all her life to retain some purchase on the social prominence that was jeopardized following the loss of General Palmer's fortune. Having an "earnest wish to gain for herself a decent independence," Elizabeth accepted menial employments in her early twenties, but she also published poems in vigorous heroic couplets on political topics, prominently including the rights of women (Marshall, 45). For a time she set her hopes on her husband, Nathaniel Peabody, but his medical practice yielded only fitful success, and the family's circumstances did not markedly improve when he decided to try his hand as a dentist. Elizabeth developed a significant career of her own as a writer and an educator; her children grew up amid the bustle of the household schools that she established, for which she wrote class materials that were subsequently published as Sabbath Lessons; or, an Abstract of Sacred History and Holiness; or, the Legend of St. George . But this career did not bring financial security, so that her oldest daughter, Elizabeth, was encouraged to begin work as a schoolteacher at the earliest possible date, as was Mary, the next oldest.

Mrs. Peabody pursued these high-minded undertakings in a social situation that riddled them with contradictions. The vision of social eminence she

derived from her memories of Friendship Hall was unrealizable in the turbulent economy of the early nineteenth century. The "unbought grace of life" that the colonial gentry transferred to America from the traditional aristocracy of Great Britain became impossible to sustain as the boom-and-bust cycles of an unregulated capitalism recurrently discomposed the status hierarchy. The New England gentry, responding to this threat by attempting to close ranks, asserted a new form of solidarity, centered on the possession and conservation of wealth as opposed to the maintenance of kin connections cutting across lines of economic difference. The separation of social groupings by levels of affluence meant that the prestige earlier attaching to names like Peabody and Palmer began to drain away (A. Rose, 5–12, 19–22).

For men, the freedom from mercenary struggle that earlier had marked social prominence was now replaced by the claim of having succeeded in that very struggle. Dramas of leisured cultivation were increasingly enacted by the wives of wealthy men, not by the men themselves. Instead of a manorial Friendship Hall presided over by a venerable old gentleman, the new emblems of status were the great McIntire mansions on the residential streets of Salem that were paid for by the profits of shipping ventures and managed by ladies of refinement.

Struggling to keep a school going and prodding her husband to greater efforts was unlike any such life. Because Mrs. Peabody was a married woman (unable to sign a contract, own property, or vote) there was no possibility that the life she led would one day be seen as a temporary encampment on the hard road to a splendid demesne. One of the lessons of Mrs. Peabody's adulthood was that a woman's self-reliant efforts, no matter how intelligent or vigorous, could not be rewarded with economic success.[4] Yet in her fierce commitment to education as a path to moral and cultural attainment, Mrs. Peabody explored alternative avenues to womanly triumph available in the rising middle-class order.

Sophia Peabody was proud to believe that the Peabodys were descended from Boudicca, the queen of the Britons, who led a bloody revolt against Roman overlordship (Tharp, 19). All three of Elizabeth Peabody's daughters—Elizabeth, Mary, and Sophia—were indomitable warriors; Sophia's distinctive armor was the identification of womanhood itself with an aristocratic spirituality, to be kept defiantly aloof from the squalor of mercenary preoccupations.

It seems that Mrs. Peabody assigned to Sophia the task of embodying what she herself had glimpsed in girlhood, the otium cum dignitate that was incompatible with the relentless striving of her adult years. On numerous

occasions Mrs. Peabody declared that Sophia, because of her "delicate" nature, was unable to make a journey, or pay a visit, or take a job that Sophia herself was quite eager to accept. When Sophia was fourteen, her sisters were teaching in wealthy households in Maine, and Elizabeth wrote home in great excitement over meeting a woman who was personally acquainted with Madame de Staël. "Madame de Stael made no distinction between the sexes," she wrote to Sophia. "She treated men in the same manner as women. She knew that genius has no sex" (Tharp, 33). Mrs. Peabody would not allow Sophia to visit her sisters in Maine.

Splitting headaches are not the same thing as aristocratic leisure, and the feminine spirituality Sophia cultivated was a virtue enshrined by the rising American middle class, not by the landed gentry of the late eighteenth century; yet in Sophia's illness these divergent themes were fused, the symbolism of elite status being refashioned in a pattern that ascribed childlike innocence and purity to women while making them exemplars of unworldly cultivation. She lay abed, able to eat no foods except those of the purest white—white bread, white meat, and milk—and, like General Palmer's daughter, suffering dreadfully at the slightest noise. Yet she also deployed her extraordinary energy and ability in the study of literature, geography, science, European and American history, Latin, French (and later Greek, Hebrew, and German), and drawing.

The special treatment accorded Sophia did not set Mrs. Peabody at odds with the two older daughters, at least not overtly. Sophia's care, as well as her education and religious training, was a project in which both sisters cooperated, and in which her sister Elizabeth took a strong hand. The whole family worked together to treat Sophia as having a distinctive quality rightly demanding the utmost solicitude from those who cared about her and appreciated who she was. All her life Sophia expressed heartfelt gratitude for the selfless devotion that had been lavished on her.

The new democratic ethos offered strong incentives to women of gentry origins who carried high abilities and ambitions into the society of post-Revolutionary America. Even as the Constitution was being drafted, Abigail Adams, recognizing that the doctrine of equal rights should apply to herself, wrote the famous letter asking her husband to "remember the ladies." The grounding of human dignity in individual striving, especially where directed toward the public good, inspired women of talent and pride to dream of high achievement; and in the generation of Sophia's mother there was little contradiction between running schools and writing about education while being a wife and mother.

Trained to boldness and independence of mind, Sophia and her sisters

expected to have "careers," lives of significant activity directed by their own choices.[5] Like men who are indoctrinated with this ideal, they faced the problem of making such lives their own, as distinct from obeying the precepts of their indoctrinators. How was Sophia to lead her own life, rather than live out a compensatory feature of her mother's? The Peabody sisters also faced additional dilemmas as the chasm deepened in their early years between a woman's domestic occupations and the world in which public achievement was possible. The undertakings that were united in their mother's life came under divergent pressures, so that the daughters were forced to choose: Elizabeth remained single as she pursued a public career; Sophia and Mary made marriages. But in the early nineteenth century these were not choices between clearly defined alternatives; each possibility was impregnated with the energies of its opposite. Like these rivalrous devoted sisters, the available possibilities were both united and at odds; and the tensions among them were at stake in the interior conflict that devastated and animated Sophia.

Sophia, whose interest in her inner life never waned, typically idealized her descriptions of formative experiences, celebrating the selfless maternal love that trained her in womanly spirituality. But when her own children were approaching maturity, she recalled a childhood experience that was "slightly bitter" and wrote it up for them in circumstances that indicate the attendant status anxieties.[6]

In March 1860, when the Hawthornes were preparing to return from England, the family made an expedition to Bath. On arriving at the railway station, they were directed to a hotel much finer than Sophia thought they could afford. A single night in such a place, Sophia wrote her sister, might consume a whole year's income. The family's sitting room was "hung with crimson," and the dining service featured the "finest cut crystal, and knives and forks with solid silver handles, and spoons too heavy to lift easily." Once they discovered that the expense was not prohibitive, the Hawthornes made the most of the occasion. Nathaniel and Sophia styled themselves "the Duke and Duchess of Maine" while Julian became "Lord Waldo," Una "Lady Raymond," and Rose "Lady Rose" (Hull, Hawthorne, 187), titles recalling the Hawthorne family legend of a vast manorial establishment near Raymond, Maine. Thus fortified with emblems of high place, Sophia drafted her story as told by "the Countess of Raymond" to "the Duchess Anna."

When Sophia was four or five years old, she was playing outdoors on a

visit to her grandmother's house and picked up a fat puppy that squirmed too hard for her to manage, slipped from her grasp and dropped to the pavement with a loud squeal. Sophia's aunt rushed from the house, shook her violently by the arm, and gave her a severe scolding. The aunt was "tall, stately, and handsome," Sophia recalled, "and very terrible in her wrath. I felt like a criminal, and as it had never yet occurred to me that a grown person could do wrong, but that children only were naughty, I took the scolding, and the earthquake my aunt made of my little body, as a proper penalty for some fault which she saw, though I did not."

The victim of an injustice that she could not articulate, Sophia is sent off to her grandmother's upstairs bedroom and there, looking out the window, she beholds her nemesis:

I saw a beggar girl, sitting on a doorstep directly opposite, and when she caught sight of me, she clenched her fist and uttered a sentence, which, though I did not in the least comprehend it, I never forgot. "I'll maul you!" said the beggar girl, with a scowling, spiteful face. I gazed at her in terror, feeling hardly safe, though within stone walls and half-way up to the sky, as it seemed to me. I was convinced she would have me at last, and that no power could prevent it, but I did not even appeal to my Grandmamma for aid, nor utter a word of my awful fate to anyone.

Sophia felt compelled to keep secret this terrifying image of her own fury. The beggar girl's wanton unprovoked rage is a perfect opposite to the speechless submission Sophia herself was then suffering, and a replication in small of the attack on her by her aunt. The threat of being "mauled" by the beggar girl could not be excluded by the bedroom walls, nor could Sophia's grandmother dispel it, and Sophia remained certain that this curse would pursue her until it was fulfilled.

It is possible that young Sophia associated the tyranny of her grandmother and her aunt with the minute supervisory attention lavished on her by her mother and sisters. But it is hardly likely that—in her little-girlhood—she connected the beggary of the urchin with the economic dependence of women and secretly sympathized with the beggar girl's defiant fury (and felt all the more threatened by it) because it symbolized a rebellion against the humiliating necessities that prompted her mother and sisters to treat her as they did. But we are not dealing here with a five-year-old's account. Sophia wrote this story after the years of puberty, in which the restriction of her life became fixed, and after seventeen years of marriage. An elaborate pattern of meaning had crystallized around the original incident, and Sophia describes an earlier encounter with the beggar girl that relates directly to her mother and includes broader themes of psychic and social subjugation.

Sophia reports that the advent of the beggar girl banished all thought of her aunt's anger; and as she gazed on the little hobgoblin, she realized they had met before. This had happened

when I had escaped out of the garden-gate at home, and was taking my first independent stroll. No maid nor footman was near me on that happy day. It was glorious. My steps were winged, and there seemed more room on every side than I had heretofore supposed the world contained. The sense of freedom from all shackles was intoxicating. I had on no hat, no walking dress, no gloves. What exquisite fun! I really think every child that is born ought to have the happiness of running away once in their lives at least,—it is so perfectly delightful. I went up a street that gradually ascended, till, at the summit, I believed I stood on the top of the earth. But alas! at that acme of success my joy ended, for there I confronted suddenly this beggar-girl,—the first ragged, begrimed human being I had ever seen.

The encounter with the urchin again takes place against the background of confinement, not at the hands of her wicked aunt, but in her beloved mother's home. The hat, gloves, and outdoor dress are paraphernalia of the genteel nurture that shackled Sophia, and her escape is an exercise of inner strength, the discovery of a larger space, the prospect of climbing to the top of the world. Yet her jubilant freedom leads straight to the encounter with a much more desperate enslavement.

What happened next was a grotesque parody of her lessons in genteel propriety: "She seized my hand, and said 'Make me a curtsey!' 'No!' I replied, 'I will not!', the noble blood in my veins tingling with indignation. How I got away, and home again, I cannot tell; but as I did not obey the insolent command, I constantly expected revenge in some form, and yet never told mamma anything about it."

The story presents Sophia as having her choice of shackles, and choosing with great energy. Fearlessly defying the "insolent" girl, she retains the dignity of her class position as a young lady. But in fleeing home she is fleeing to a world of curtsies, not enforced with rough commands, but enforced nonetheless.

As she amalgamated the two incidents, Sophia became fascinated by the word mauled . "What was that? Something doubtless, unspeakably dreadful. The new, strange word cast an indefinite horror over the process to which I was to be subjected. Where could the creature have got the expression?" Not only does the beggar girl know about curtsies, but she has also acquired somewhere a relatively sophisticated vocabulary. As her years unfolded, Sophia had good reason to dread the prospect of collapsing, with all her education and sensibilities, into poverty. She knew she did not have family

wealth by which to bankroll a life of genteel invalidism, and when the time came for her to scramble for her own living—by way of editing Hawthorne's notebooks after his death—she proved fit for the task. Other New England women of her class and generation did not fare so well and suffered the degradation of carrying their cultural attainments into circumstances of financial ruin and of watching their children grow up in squalor.[7]

The conventional recourse for a woman in Sophia's circumstances was to uphold the standard of womanly refinement whose imperatives were as harsh as those of the beggar girl but which served as the regalia of the emerging middle class. If a growing girl failed to attain the selfless delicacy of a "true woman," she risked falling into the working class, or beneath, where beggars and bullies lived out their desolate lives and sought occasions for taking futile vengeance on their social superiors, or on the working-class women who often served as vicarious targets. For a woman to unsex herself by asserting her aggressive impulses (to say nothing of her erotic impulses) was to invite consignment to this outer darkness, which was the sharpest social terror now assailing the old New England gentry, that of failing to negotiate the transition into the new elite and falling into laboring-class degradation.

Sophia's story is a parable of the cross-pressures inherent in the ideal of womanhood she sought to make her own. The beggar girl polices the genteel "feminine" order by reduplicating its commands with harsh clarity and by reminding the potential rebel of what lies outside. She is thus the object of the policing action she herself executes. The story invests the beggar girl with two opposed impulses, both of structural significance to the emerging gender arrangement as Sophia came to embody it: violence exploding in opposition to the standard of womanhood that was set before her as mandatory, and violence exerted to support the same standard.

The horror Sophia felt at the prospect of being "mauled" by this figure was generated by the psychosocial contradiction grinding away in her own personality. Her life was conditioned permanently by a psychic autoimmune reaction in which, spontaneously and with fierce dedication, she sought to rid herself of the very qualities of fierce spontaneity that were built into the reaction itself. A feedback loop of inner conflict was established that could be set in motion by a slight external irritation and would then, under its own self-driven dynamic, crescendo to a mind-splitting roar. The experience of being ripped apart, of being made into an "earthquake," of being "mauled," of being "destroyed": all these were imposed on her by the inherent contra-

dictions of a social situation that both cultivated and repressed the direct exercise of her native force.

Sophia managed to place her conflicts—and the illness to which they led—in the service of her own initiative, wresting a degree of mastery from the conditions of her victimization. She became a careful student of her own condition, and as one doctor after another proved unable to "cure" her, she emerged as an authority on the treatment she required. "This morning I awoke very tired," she writes in her journal, "& as if I must take some exercise to change the nature of the fatigue—so although it snowed & Molly [her sister Mary] thought it 'absurd'—I took a drive with Mamma for half an hour & as I expected was relieved of the vital weariness, though I acquired physical." Noting that Mary considers her "wilfully & foolishly imprudent," Sophia insists that she is herself the only judge because the knowledge of her pain is incommunicable. "Heaven grant," she piously concludes, "that none may through experience understand the excruciating sensation I perpetually feel."[8]

Sophia found one avenue toward mastering her condition in the conviction that it offered spiritual insight. Having disposed of Mary's claim that the sleigh ride was "absurd," Sophia turns to comment on the opinion of a physician she admired: "Dr. Shattuck was right when he so decidedly declared I never should be relieved 'till I heard the music of the spheres'—in other words—till I had put off corruption." Sophia here is not anticipating her own death but referring to a mystical transaction in which her miseries are sublimated in a communion with the divine. The inner conflicts that threatened her with psychic disintegration also gave her experiences of transcendent harmony.

Sophia cherished throughout her life a girlhood dream that portrayed this process, recounting it to her children and to intimate friends as an emblem of her essential spirituality. The dream—as Julian described it—was "of a dark cloud, which suddenly arose in the west and obscured the celestial tints of a splendid sunset. But while she was deploring this eclipse, and the cloud spread wider and gloomier, all at once it underwent a glorious transformation; for it consisted of countless myriads of birds, which by one movement turned their rainbow-colored breasts to the sun, and burst into a rejoicing chorus of heavenly song" (NHW 1:49).[9]

This is not a dream about a silver lining, or about the sun bursting through a cloud, but of the whole cloud instantly transformed into a heavenly chorus. Sophia would certainly have agreed that the process depicted here is "sublimation," inverting the post-Freudian sense of the term, in which the earthy desires sublimated are considered to be real. Sophia's inward experience attested a central axiom of romantic Neoplatonism, that sublimation gives access to the sublime, the movement from earthly murk into radiant spiritual truth taking place at a single step. As her son declared, the transcendental ontology of Sophia's dream was "among the firmest articles of her faith" (NHW 1:49).

Sophia's experience of redemptive communion with the divine meant that her agonizing sensitivity counted as a moral litmus, unerringly reactive to earthly evils. Since freedom from nervous headaches required "putting off corruption," she acquired a command post within the consciences of all who knew and understood her. Her sister Elizabeth remarked on the voluntary acquiescence Sophia's needs inspired. "All these years mother was her devoted nurse,—watching in the entries that no door should be hard shut, etc. . . . I had a school of 40 scholars, and she became interested in them, and they would go into her room; and the necessity of keeping still in the house so as not to disturb her, was my means of governing my school: for they all spontaneously governed themselves" (Pearson, 272–273).

Elizabeth was one of the most forceful and accomplished American women of the century, accustomed at an early age to managing her own life and to setting plans for others to follow. After opening a school in Brookline in 1825, she became a friend and disciple of William Ellery Channing, with whose endorsement she enlarged her school and took on as partner a prominent teacher of elocution named William Russell. By 1828 the whole family had moved from Salem to Boston, and Elizabeth's long career of educational and cultural leadership in that city commenced. Elizabeth knew a struggle for dominance when she saw one, and she was frankly astonished at Sophia's successes. "I never knew any human creature who had such sovereign power over everybody—grown and child—that came into her sweet and gracious presence. Her brothers reverenced and idolized her" (Pearson, 273).

Sophia found it virtually impossible to act frankly in her own behalf because self-assertion invited a "nervous" attack. At age thirteen she discovered, for example, that she had an exceptional talent for drawing and painting, yet the first dawning of this realization brought on a bout of incapacity. "She was thrown into a sickness," her sister observed, "from which she never rose into the possibility of so much excitation again; and by

a slight accident was disabled in the hand and could not draw" (Pearson, 272). When Sophia returned to drawing and painting several years later, she sought to resolve this dilemma by becoming a copyist instead of creating her own pictures.[10] She soon became so skillful that knowledgeable observers could scarcely distinguish her work from the originals, and her copies of pictures by Washington Allston, Chester Harding, and other leading painters were much in demand.

Sophia was both fascinated and repelled by Elizabeth's public enterprises. Sophia sent letters home from Cuba, which her sister circulated among friends in Boston, and before the year was out, Sophia's "Cuba Journal" had made a name for itself. Word got abroad that Sophia's "effusions" were "ravishing," so that Elizabeth was able to organize readings for invited guests that on some occasions ran as long as seven hours (Cuba, xxxviii). Sophia professed herself "aghast": "I do not like at all that my journal should be made such public property of—I think Betty is VERY naughty. . . . I assure you I am really provoked. I shall be ashamed to shew my face in the places that knew me—for it seems exactly as if I were in print—as if every body had got the key of my private cabinet & without leave of the owner—are appropriating whatever they please" (249, 470–471). Elizabeth in reply urged Sophia to publish in The Atlantic Monthly, which Sophia refused to do. Early in their courtship, however, she offered the journal to Nathaniel Hawthorne, who—doubtless pleased at being handed the key to her private cabinet—copied sections of it into his own notebook. From him she received a recognition suited to the sovereign aloofness she wished to maintain: he called her the "Queen of Journalizers" (xxxix, xli).

Elizabeth and Sophia present a contrast of spirits deeply alike. The pressure Elizabeth exerted against the conventions of domesticity in her public undertakings was felt by Sophia as an inner imperative, as was the pressure of those conventions themselves. Sophia's psychic struggle was an internalized version of the conflict Elizabeth waged outwardly, so that the drama and danger of Elizabeth's public career were recapitulated as a subjective experience by her younger sister.

Sophia describes her artistic endeavors in the winter of 1832 in language that indicates the blend of overpowering excitement and overpowering dread that accompanied the effort to put her talent to work. "Yesterday I began copying Mr. Allston's picture," she begins.

It was intense enjoyment—almost intoxicating. It was an emotion altogether too intense for my physicals. A most refined torture did it work & has it worked today

upon my head—accompanied with a deathly sickness. After a ride yesterday the sickness passed away in a degree & left . . . [a] headache which seemed to exalt every faculty of my mind & everything of which I thought was tinged with a burning splendor which was almost terrible & I did not dare to let my imagination excurse.[11]

Observe the fusion of seemingly contradictory emotions. The ecstasy that she expresses in sustaining "a refined torture" is masochistic, yet at the heart of this ravishment is the purposeful exercise of her talent. To "excurse" is to play with fire, a daring and passionate adventure of the mind along the borders of insanity. "What do you think I have actually begun to do?" she writes to Elizabeth on another occasion. "Nothing less than create and do you wonder that I lay awake all last night after sketching my first picture. I actually thought my head would have made its final explosion. When once I began to excurse, I could not stop" (Tharp, 55).

Sophia's effort to comprehend her experience took the path marked out by her Neoplatonic faith. Instead of examining the concrete dilemmas of being a woman, and of being Sophia Peabody, she undertook a meditative exploration of transcendental realities. Here is a journal entry from her twentieth year:

A dubious morning. I felt rather as if a tempest had passed over & crushed my powers when I awoke—for such a violent pain—while it is on me, gives me a supernatural force—combined with an excessive excitement of all my tenderest nerves, which nearly drives me mad. Yesterday whenever a door slammed or a loud voice made me start throughout in my powerless state—I could not keep the tears—burning tears from pouring over my cheeks. . . . Oh how mysterious is this unseen mighty agent. There is evident reason why a murderous instrument should cause anguish—but how is this inward-invisible agony caused? It seems as if a revelation had passed in my head & that I can no more mingle with the noisy world.[12]

Sophia sustains a supernatural revelation that would not have seized her if she were free of her malady. On the journey to Cuba, undertaken in hopes of a cure, she commented on the spiritual loss entailed by getting well: "I believe I understand in a degree the very great blessing of sickness. . . . Coming years of 'Health' never can be so dear to me as the past years of suffering—I shall go back to them as I would enter the inner chamber of the tabernacle where the throne & the ark—were filled with the presence & commands of the Invisible god (Cuba, 250).

Sophia's pain exalts her from the earthly to the divine by making her

preternaturally aware of the intricacy of her psychic and physical organization, and thus of her own miraculous character as a creation of God. If she were merely a "nervous" woman, she affirms, her mind would have collapsed under the pressure; instead, she is a visionary prophet.

We are indeed fearfully & wonderfully made, & no one can know how fearfully till they are sensitive in the nicest parts of this wonderful machinery—If I had been nervous in the common acceptation of the term, I think I should not only have been mad, but afraid to move or feel. . . . In the extremity of my suffering when I was conscious of a floating off of my senses—a resolute fixing of my mind upon immutable, never changing essence . . . has enabled me to regain my balance so entirely that I feel as if I had had direct revelation to my own mind of the existence of such a Being.

(Cuba, 252–253)

This interior experience opened Sophia's mind to the Godhead spiritually immanent in the creation, not merely to the rational order that natural theologians like William Paley found in it. Sophia's romantic ecstasy testified directly to the great soul pervading nature, the local syntax of her ego dissolving into the universal discourse. "When the omnipresent beauty of the universe comes & touches the cells of Memory," she wrote home from Cuba, "& has an answer from all our individual experiences of the beautiful in thought & act during the Past—& blending with the Present—in symphonious oneness—carries us on to the future by the power of that trust or faith which is nobler because more disinterested than any other attitude of the mind, connecting all. . . . There is no need of logic to convince the hearkening spirit that there is a God—Knowledge by intuition is the unerring truth" (Cuba, 585).

If Elizabeth had succeeded in publishing the Cuba Journal in 1833, Sophia Peabody would be numbered among the earliest public exponents of transcendentalist spirituality. Both sisters were caught up in the ferment among young Unitarian clergymen who were inspired by Wordsworth, Coleridge, and Carlyle and who published articles in the Christian Examiner seeking to articulate the new consciousness.

Elizabeth had taken charge of her younger sister's education when Sophia was five years old and had inculcated Unitarian convictions regarding rational virtue and the perfectibility of human nature, scrupulously shielding her from the "terrible doctrines" of Calvinism (Pearson, 270). By the time Elizabeth moved the family to Boston in 1828, she was already attuned to the themes in William Ellery Channing's teaching that encouraged the development of transcendentalism and caused the leaders of the new movement to look on him as a spiritual father. Elizabeth is best known for the practical

support she provided for transcendentalists, for her role in Alcott's Temple School, and for establishing the West Street Bookstore, where The Dial was published and Margaret Fuller held her conversations. But Elizabeth was intellectually active as well; she published a series of articles titled "The Spirit of the Hebrew Scriptures" in the Christian Examiner for 1834—grounded on her own reading of the Hebrew and of German criticism. Her ideas greatly alarmed Professor Andrews Norton of Harvard, a defender of Unitarianism against the new movement, so that he ordered the cancellation of Elizabeth's series after the third of her six articles had been published (A. Rose, 54). When Frederic Henry Hedge formed the Transcendental Club in 1836, Elizabeth Peabody (and Margaret Fuller) were invited to join (Miller, 106).

Sophia quickly accepted the transcendentalist doctrine most alarming to orthodox Unitarians, namely that spontaneous impulses of the soul could serve as a guide to truth, replacing the cold conclusions of reason. Unitarians were especially touchy on this point because their Calvinist opponents had claimed all along that liberal worship of reason would lead in the end to wanton irrationalism, and the transcendentalists appeared to fulfill this prophecy. Because it advanced the claims of religious intuition, an 1833 article on Coleridge by Frederic Henry Hedge was seen by proponents of transcendentalism as the "first word" uttered in public in behalf of the new spirituality (Miller, 67).

Sophia started reading Coleridge in 1830 and attempted a conclusion to the unfinished "Christabel."[13] On the journey to Cuba three years later she was ready to articulate the relationship between Coleridge's romantic ontology and her own aesthetic raptures. "A forest always seems to me to have intelligence—a soul—The trees seem a brotherhood—Especially when they are all motionless—It must be the 'intellectual breeze' of which Coleridge speaks, that wakes that feeling within us, in the presence of nature, or 'the intense Reply of hers to our Intelligence' & we are the 'harps diversely framed'" (Cuba, 480).

In reply, Elizabeth sounded a note of caution that echoes the Unitarian resistance to transcendental teaching and serves as yet another reminder of the way issues of the public controversy were also fought out within the partisans. "Sentiments about Beauty," Elizabeth declared, "do not constitute Religion" (Cuba, xxxiii).

Early in 1835 Sophia drafted a meditation in her personal notebook concerning Coleridge and Plato, exploring the union of self-knowledge with knowledge of the transcendent: "To study our own Life is to study all Life—since in this Life of ours are emblems and representations of every

form and power and spirit of life. And this is Life—to apprehend . . . the Ideal that images itself in our Being, wherein by self study & self representation, sustained and purified by the Actual not less than by the Speculative powers, we find the Absolute, All Representing One, and finding Him we know & in Him image ourselves."[14]

The purity of soul required for such knowledge, Sophia explained, was possible only for those unsullied by traffic with this world. Far from lamenting her lengthy postponement of conventional adult responsibilities, she celebrated childlikeness. "In the heart of Infancy do I hope for that Light & Life to spring that shall regenerate the Philosophy and Life of future Time, when Literature shall flourish in the greenness of youth . . . when Language shall become the transcript and representative of the unshadowed Life of Childhood."[15]

Sophia rejected the suspicion that her childlike consciousness was merely naive and that her convulsive recoil from the "earthly" might blind her to realities that deserve to be taken seriously. "My meditations turned upon my habit of viewing things through the 'coleur de rose' medium," she wrote, "when suddenly, like a night-blooming cereus, my mind opened, and I read in letters of paly golden green, words to this effect. The beautiful and good and true are the only real and abiding things, the only proper use of the soul and Nature. Evil and ugliness and falsehood are abuses, monstrous and transient. I do not see what is not, but what is, through the passing clouds."[16]

Sophia thus adopted an understanding of evil as nonbeing that found expression in the romantic religion diversely articulated in Massachusetts by Emerson and Mary Baker Eddy. To Sophia, as to Emerson and Eddy, the perception of evil is a defect of spiritual sight that leads people to mistake the transient clouds of earth for the eternal sunlight passing through them. But the essential quality of Sophia's mind is not in the conclusions she reached, but in the vigor with which she pursued her spiritual excitements. Well before Emerson issued to the Phi Beta Kappa society at Harvard College his dictum that "the one thing in the world, of value, is the active soul" (Whicher, 68), Sophia was living it out.

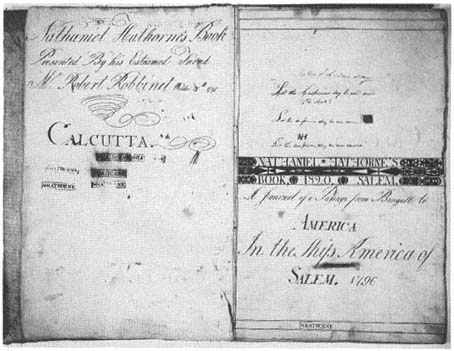

She was Woman Thinking, and she laid claim to the poetic power of vision according to which the ennobled spirit is able to refashion reality itself. Yet the plastic power of her eye and its expression in language were only subordinate modes—romantic doctrine equally affirmed—of her personal presence, which brought this creative force to bear on other souls (Fig. 2). "Natures apparently far sturdier and ruder than hers depended upon her, almost abjectly, for support," Julian declares. "She was a blessing and an

Fig. 2.

Sophia Hawthorne as a young woman

illumination wherever she went; and no one ever knew her without receiving from her far more than could be given in return. Her pure confidence created what it trusted in" (NHW 1:48).

Sophia's piety retained a strongly social meaning. Like those throughout New England who responded to transcendentalist doctrines, Sophia felt a desire to buttress an elite identity that was increasingly threatened in the rising commercial economy. Without inherited wealth to defend, transcendentalists asserted an aristocracy of intellect and virtue against whose lofty standards of taste and moral cultivation the rude multitude could plausibly

be scorned or made targets of "improving" enterprises. In Transcendentalism as a Social Movement Anne Rose discusses the defensive consolidation of wealth that split the old elite class into affluent and penurious sectors, and she ably portrays the radical critique of contemporary social developments that the transcendentalists provided; but Rose does not notice the reactionary and defensive impulses arising from the transcendentalists' own elite identity, which they shared with doctrinal antagonists among the Unitarians and Calvinists, as against vulgarian Methodists, Baptists, and the Roman Catholic Irish.

Sophia was aware that the economic instability of American society was forcing a revision in the way elite status was marked. "In America," she wrote in her commonplace book, "greatness can never be predicated of a man on account of position—but only of character, because from the nature of our institutions, place changes like the figures of a kaleidoscope—and what is a man profitted because he has been a President—a Governor, or what not. This comes near to showing how factitious is all outward rank and show and especially American rank & show. In the old world birth, culture, permanence and habit give more prestige and Quality."[17] Sophia's yearning for the "Quality" conferred by Old World position carries over into the vocabulary she uses to describe the greatness of character that distinguishes superior persons in the New World: they are a nobility whose station is permanent because it is rooted in the eternal.

The transcendental ecstasy in which Sophia gazes out over the Cuban landscape vindicates her claim to aristocratic pre-eminence: "I felt like an eagle & like the Queen of all I surveyed." Sophia was well aware of speaking here for a community of moral sentiment. She articulates what Emerson and Thoreau were to establish as a commonplace of romantic revolt, namely that the true possession of property is enjoyed by those who respond to its inherent poetry, not those who hold the deeds to it. "We who enjoy it, not in proportion to the revenue of gold it yields to our coffers, but in the infinite proportion of unappropriating & immaterial pleasure it pours into our hearts. . . . We it is who possess the earth. It was mine that morning—I was the queen of it all" (Cuba, 566–567).

Sophia was painfully aware that she was not rich: her life of leisure on the Cuban coffee plantation was purchased through the efforts of her sister Mary, who worked in the household as a governess. Sophia realized that cultivated persons may be placed at the mercy of vulgar souls who have the money to hire and fire them. She writes home from Cuba sympathizing with the effort of a Mr. Gardiner to find a teaching job where his "disinterested,

uncalculating, elevated soul" would be properly appreciated, and she lashes out at Salem, where the leaders of society are indifferent to Mr. Gardiner's value, because in Salem "the God Mammon decides all ranks & degrees." Sophia detested the formation of a new moneyed class from which she was excluded: "Oh mean & pitiful Aristocracy! even more despicable than the pride of noble blood & of bought titles!" (Cuba, 305).

Sophia thinks of herself as a queen set apart from the corrupt British aristocracy yet also distinct from the American high priesthood of Mammon. Her response to the troubles of yet another noble-souled teacher—Francis Graeter, who had been her drawing instructor—displays the humiliation and fury at stake in her claim to exalted status:

When you speak of the treatment of our friend Mr. G by the purse-proud mean-souled aristocracy of Salem, my soul is just like a volcano spouting fire & flame. . . . I wonder when the day will come that man will consider money as nothing but a trust for the good of others—instead of making a throne of base metal to sit thereon & look down with disdain upon the far nobler, far more exalted crowd below, who have not the pitiful & dangerous advantage of dollars & cents—but nevertheless are the true & unacknowledged nobility of God's kingdom.

(Cuba, 410)

Sophia envisions a nobility consisting of persons like herself, and she now had a system of religious ideas to account for her own experience and that of her spiritual kindred. The cruel fate of such exalted spirits is to live perforce in a materialistic self-seeking society. Their sufferings appeared to Sophia—like her own sufferings—to be evidence of exceptional stature. "I do not realize how coarse & rough the world is till I see the crushing & bruising of an exquisitely attuned nature under its trampling foot." The victims of this rude world should not give way to despair, she declares, but should remember that vindication is in the hands of God.

Francis Graeter's difficulty in making a living reminds Sophia of her own brother Nathaniel, who seemed unable to find a purpose in life. The idea strikes her "with overwhelming force" that Nathaniel is at heart an artist:

I thought of his contemplative, gentle, uncalculating—solitary disposition—his love of being by himself—his abhorrence of bustle & noise—his fits of abstraction—his purity and singleness of mind—his difficulty in realizing that there could be cheating & falsehood in the world, & it struck me as with a flash of lightning that a great mistake had been made, that God designed him for an artist & that we had been pushing & urging him against his organization & natural gifts.

(Cuba, 411–412)

Sophia imagines here a fit companion for herself, and her imagination races forward to picture their working together. "Nothing must be done rashly," she tells her mother,

but I want to fly home, put the pencil into his hand, & see what he would do at once, giving him the idea that he could do any thing. . . . How delightful to think of having a bona fide brother artist—I could colour & he, with his exquisite truth of eye, could draw & we could be all to one another that each is wanting in. He could illustrate story books—& help me draw my men and women in my landscapes—& we should be as happy as a king and queen in fairy land with creating wands in their hands.

(Cuba, 413–414)

It had long been understood that Sophia would never marry, principally because she looked on herself—so her sister Elizabeth remarked—"as a little girl" (Pearson, 267). Sophia's disabilities rendered her incapable of keeping house with her mother, and marriage would surely entail the added burdens of rearing children. The obstacles to marriage, however, were not only practical. What mate could be found for such an extraordinary being, deep within whose character there lay a violent conflict in which "submission" embraced a vehement self-assertive ambition? Her ambition, moreover, reached out to include projects that could be paid for only by a well-to-do husband.

Sophia envied an elderly Mrs. Kirkland in Salem, doubtless one of the aristocracy of Mammon, who had taken an exciting trip to the Near East. "Shall I ever stand upon the Imperial Palace of Persepolis? Who knows but when I am dried to an atomy like Mrs. Kirkland. . . . And when I go, perhaps my husband will not be a paralytic. Oh! I forget. I never intend to have a husband. Rather, I should say, I never intend any one shall have me for a wife" (NHW 1:185–186). Sophia puts her finger exactly where the central problem lay, not in "having a husband" but in being "had." Subordination to the authority of a man seemed inseparable from marriage, especially if the man—unlike her father—were capable of achieving worldly success sufficient to pay for a journey to the East. In erecting a transcendental philosophy on the sublimation of her inner torment, however, Sophia had opened a way to find a suitable kindred spirit.

The tenuousness of Sophia's membership in the "nobility of the Kingdom of God" comes through clearly in the manic excitement with which she claims it. Was it a nobility only of spiritual communion, or could it be perpetuated on this earth through a noble marriage? How many young men were available who had kept themselves in childlike innocence, unspoiled by

the world, and could also manage to support a wife? These were urgent issues of Sophia's experience when she discovered in 1837 that just a few streets away, in her own home town of Salem, there had lived for years in quiet seclusion a man of unearthly beauty writing great works of literature.

Toward such a figure the yearnings of Sophia's royal soul could be directed: her desire for a life of heroic sacrifice, in which her achievements would be selfless because they were the achievements of another, and her wish to exercise her spiritual influence, strengthening the divine spirit in the artist as he struggled to keep his own supernal vision undimmed by earthly distractions. Here was a relation in which the deepest submission, the most reverent obedience, could lead to a spectacular triumph.

As they were just becoming acquainted, Sophia made the following remarks: "Mr. Hawthorne said he wished he could have intercourse with some beautiful children,—beautiful little girls; he did not care for boys. What a beautiful smile he has! . . . He said he had imagined a story, of which the principal incident is my cleaning that picture of Fernandez. To be the means, in any way, of calling forth one of his divine creations, is no small happiness, is it? . . . He has a celestial expression. It is a manifestation of the divine in the human."[18]

As her wedding approached, five years later, Sophia rejoiced that her membership in the nobility of the kingdom of God would soon be sealed for all eternity, by way of marriage to the King. "I marvel how I can be so blessed among mortals—how that the very king & poet of the world should be my eternal companion henceforth. . . . Time is so swallowed up in Eternity now that I have found my being in him, that life seems all one—now & the remotest hereafter are blended together. In the presence of majestic, serene Nature we shall stand transfigured with a noble complete happiness."[19]

Chapter Four—

Portrait of the Artist as a Self-Made Man

Late in life Hawthorne explored his solitary personal anguish in terms that sketch an emerging commonplace of his time:

If you know anything of me, you know how I sprang out of mystery, akin to none, a thing concocted out of the elements, without visible agency—how, all through my boyhood, I was alone; how I grew up without a root, yet continually longing for one—longing to be connected with somebody—and never feeling myself so. . . . I have tried to keep down this yearning, to stifle it, annihilate it, with making a position for myself, with being my own past, but I cannot overcome this natural horror of being a creature floating in the air, attached to nothing; nor this feeling that there is no reality in the life and fortunes, good or bad, of a being so unconnected.

(CE 12:257–258)

This wrenching lament is spectacularly at odds with the story of Hawthorne's boyhood. Far from being alone, Hawthorne grew up in a welter of kinfolk. He was born in his Hathorne grandmother's house on Union Street in Salem, where his mother and older sister crowded in with Ruth and Eunice, his two unmarried Hathorne aunts. Here his father lived during the intervals between ocean voyages, and so did his uncle Daniel Hathorne, who was also a ship-captain.

When young Nathaniel was four years old, after the birth of his younger sister, word arrived in Salem that his father had died of yellow fever in Surinam. Nathaniel's mother then moved with him and his two sisters back

to the Manning family home where she had grown up, and where her parents presided over a household that included her eight brothers and sisters. The Manning house faced on Herbert Street but adjoined the Hathornes' by way of a back lot on which the children played, so that young Nathaniel was immediately surrounded in the early years by over a dozen close relations, apart from his mother and sisters and not including his aunts Sarah Hathorne Crowninshield and Rachel Hathorne Forrester, to whom he refers familiarly in early letters, who had homes of their own where he and his sisters were welcome (CE 15:117–118, 126–127).

Yet in picturing himself as a lad without connections, burdened with "making a position for myself," Hawthorne recapitulates a typical irony in the social construction of the self-made man. Mary Ryan's Cradle of the Middle Class studies the family histories of men in Utica, New York, who embraced the gospel of self-help and were celebrated for having pulled themselves up by their own bootstraps. Ryan describes a pattern to which Hawthorne's early life corresponds, in which a collective family strategy is put in motion to supply funds for advanced education and provide a place for the young man to live inexpensively during the early years of adulthood as he gets his career underway (166–169). To refashion such a story of marked dependency into a myth of self-creation required attributing the work of tangible exterior resources to an inward spiritual potency. The denial of an indispensable support network and its absorption into the self-creating self enacted in the careers of business and professional men were also at the heart of Emerson's vision of the selfhood from which a uniquely American intellectual and poetic achievement would spring.[1]

Sophia had invented Nathaniel before she met him, formulating her ideal of the brother-artist as a nobleman in the kingdom of God. When Nathaniel met Sophia, by contrast, he was struggling to invent himself and loved her for her role in that enterprise. To say that Hawthorne's identity as a writer is rooted in social circumstance is not to deny what was strikingly unusual in his experience. Comparatively few boys lost their fathers in boyhood as Hawthorne and Emerson did; this exceptional experience, however, placed these men (as analogous circumstances placed Melville, Thoreau, and Whitman) in a situation that accentuated conflicts typical of the era: in male relations both with fathers and with patriarchal authority in general. The same is true of Hawthorne's relation to Sophia: it was markedly unusual, but certain of its features make it typical of the social arrangements that gave rise to the domestic ideal. The "cult of domesticity" envisions a self-made man taking to wife an angel, a figure whose religious energies counteract the unreality "of a being so unconnected" as himself.

Like Sophia, young Nathaniel Hawthorne found a "delicate" physical condition useful in managing the internal conflicts that were consolidated into his vocation as an artist. When he was nine years old, he spent more than a year recovering from an injury to his foot that occurred when he was playing with a bat and ball. A procession of local doctors, including Nathaniel Peabody, came through the household to give their opinions. It seemed the boy was unable to walk on the injured foot; then it seemed he simply refused to walk on it. As the months passed by, Nathaniel hopped about the yard or used a crutch to get around; he played with his kittens and read what he wanted to read. A teacher brought in to carry on with his schooling did not find him zealous to follow directions. On the contrary, the boy took the occasion to do just as he pleased. "He amuses himself with playing about the yard, and in Herbert St. nearly all day," his Aunt Priscilla Manning tartly observed.[2] The doctors warned that the foot would not improve without exercise and noted with alarm that it did not seem to be growing properly. Dr. Smith of Hanover, perhaps suspecting a psychic cause, determined that the lame foot would benefit from cold water poured over it every morning. This advice was followed religiously, and in the following January the family rejoiced at young Nathaniel's full recovery. A more severe illness soon after, however, made the family fear he would always be lame, if he survived.[3]

It's almost too perfect, this psychologically loaded incident from the boyhood of a man who had trouble learning to stand on his own two feet, the lad refusing to walk so long as there appeared no path before him that he could call his own. Yet the evidence is compelling. Hawthorne's boyhood illnesses "conspired," his sister Elizabeth recalled, "to unfit him for a life of business," and she noted that Hawthorne's lifelong "habit of constant reading" began during this seeming idleness. The suspension of his formal schooling marked his decisive entry into the world of books, which he would eventually command. Self-direction was essential to the development of Hawthorne's true nature, Elizabeth maintained: "intentional cultivation" would have spoiled his talents. If "his genius had not been thus shielded in childhood," she explained, Hawthorne would never have developed "the qualities that distinguished him in after life."[4] These fourteen months are a harbinger of Hawthorne's "long seclusion" in Salem after college, when he likewise cultivated his genius in his own way.

Studies of Hawthorne's development as an artist generally agree that he needed independence to provide for an innate imaginative power. Such a view is in keeping with the romantic conception of the artist's imagination as an ontological fountain, pouring forth beauty and truth from its own self-contained energies or by way of its contact with transcendental reality.

Nina Baym affirms that Hawthorne's career is given shape by a struggle between the claims of such an imagination and Hawthorne's effort to make his writing acceptable to a "skeptical, practical-minded audience" (Baym, Career, 8). Yet Baym discovers that this audience celebrated Hawthorne loudest when he took his stand—in The Scarlet Letter —on the artist "as an independent person responsible only to his art and to himself" (112). Hawthorne's ascent to fame, rather than confirming the power of a freestanding imaginative faculty acting in defiance of social expectations, recapitulates the ironical conventions of fulfillment that an "individual" perforce obeyed in a society of self-made men. Like many another aspirant to middle-class success, Hawthorne had misfired when he "dependently courted public approbation" only to be "rewarded for independence" (151).

Hawthorne's stance over against the familial community of his boyhood foreshadows the preference for solitude—and the anguish of solitude—that characterized his adult life. But this stance did not originate in his artistic vocation. On the contrary, his artistic vocation offered him one way of managing the psychosocial conflicts that led him to think of himself as a unique being, uniquely obligated (and uniquely entitled) to follow his own destiny. Young Nathaniel did not choose these generative conflicts, which, though intimate, were not private. The symbolic energies surrounding and penetrating the psychic space he claimed for himself were inherent in the large familial community in which he grew up and were linked in turn to the broad-scale social changes amid which self-making emerged as an ideal of male identity.

Hawthorne did not occupy alone the domain of independence that his foot injury provided; he shared it with his mother and sisters. The complicated community of Hathornes and Mannings in the two neighboring houses takes on a starkly contrastive design very early in Nathaniel's responses to it; both the Hathornes and the Mannings appear as aliens, menacing the fragile quartet of mother, daughters, and son.

Students of Hawthorne's life have given careful attention to the atmosphere of the Manning household—its bustling commercial spirit and the psychosexual crosscurrents running through it—and have demonstrated its lifelong impact on Hawthorne and his work.[5] Yet we would hardly be alerted to the Mannings' existence from what Hawthorne himself said in his volumi-

nous journals and correspondence. His earliest letters express regret at his depending on them and at his mother's depending on them, and then the record goes silent. What little we learn from later years speaks of an icy estrangement and even of vengeance. He pointedly did not attend the funeral of his uncle Robert, who had borne most of his educational expenses. When his own political influence was at its zenith, after Pierce's election to the presidency, Hawthorne wrote a curt letter endorsing his uncle William Manning's effort to get a job as a janitor at the Salem Custom House (CE 16:682). In 1855 he instructed his publisher to make payments "to the extent of $100 (one hundred dollars) for the benefit of W. Manning, an old and poor relation of mine" (CE 17:422). The surviving record gives scant evidence that Hawthorne felt gratitude for the treatment he had received when he was himself the poor relation.

Spurning the Mannings did not mean embracing the available Hathornes. Although the biographical record here is even slimmer, it suggests a corresponding alienation. On a visit to New Haven in his twenties Hawthorne encountered a young man who knew Salem society and who remarked that he didn't "in the least resemble any of the Hawthorne family." To this Hawthorne replied "with considerable force and emphasis. 'I am glad to hear you say that, for I don't wish to look like any Hawthorne.'" (M. Hawthorne, 264–265).

Hawthorne did not make such gestures of repudiation to defend himself as an artist-in-the-making; they began before he entered on that venture and continued long after he had succeeded in it. They arise from a conviction of radical uniqueness that he, his sisters, and their mother cherished in their bereavement. The death of Hawthorne's father sharpened a chronic tension between the Hathorne and Manning households that would have been present even if no marriage had taken place between them, because of the uneasy relation between their social positions.

There were no pre-Revolutionary landed gentry among the Hathorne forebears. Such eminence as the family had enjoyed in Puritan times had declined by the middle of the eighteenth century. Paul Boyer and Stephen Nissenbaum's Salem Possessed demonstrates clearly that the Hathornes were on the wrong side of the witch controversy, economically as well as morally. Hawthorne was right in sensing—as he says in the introduction to The Scarlet Letter —that the deterioration of the family's fortunes was somehow linked with his ancestors' role in those old persecutions. The economic future in Salem lay with the shipping industry, not the farming community where the Hathornes had their stronghold. Hawthorne's great-grandfather was a

farmer of modest means whose sons commanded ships they did not own. Hawthorne's father was a ship-captain, we've seen, who at the time of his death had not managed to move his wife and three children out of his mother's home; no one on the Hathorne side of the family stepped forward to support this small cluster of recent offspring.

Yet as the nineteenth century dawned in Salem, old family connections still counted for social rank, in a restive competition with new wealth. The Hathornes retained an air of social ascendancy, which made the Hathorne daughters attractive to men who had acquired fortunes in the burgeoning commercial economy and wanted to ally themselves with a distinguished name. Hawthorne's aunts Crowninshield and Forrester might be thought to have married "down" socially; they had certainly married "up" financially. Their husbands were among the new rich; and Hawthorne's father turned to them for employment. The Hathorne family experience suggests that among members of the declining pre-Revolutionary elite, women found better prospects through marriage than men did through careers; the social pretensions that disabled men from competitive enterprise made women suitable ornaments of hard-won success. Nathaniel Hathorne's marriage to Elizabeth Manning did not, however, match a woman of position to a man of means.

The most memorable story of the ancestral Mannings was a trial and conviction for incest that took place at Salem in 1680.[6] The Manning forebears were known for sexual misconduct, and the old Hathorne magistrates were famous for punishing it. By the early nineteenth century Elizabeth Manning's family was less wealthy than the Crowninshields and Forresters, but their prosperity considerably exceeded that of the Hathornes; and the Mannings' current affluence had been gained in the expanding commercial economy. Elizabeth's father had begun as a blacksmith and then made his fortune as owner of the Boston and Salem Stage Company.

Elizabeth Manning was two months pregnant when she married Nathaniel Hathorne, which suggests that the match between them arose from a mutual attraction exercised in defiance of family preferences.[7] Elizabeth's marriage stands out against the strong ethos of joint effort that bound together the multi-generational Manning household, aimed at keeping the family businesses thriving: none of Elizabeth's brothers or sisters married until fifteen years after her marriage to Nathaniel Hathorne. Since Hathorne was not capable of setting up a household, the marriage can hardly have

appeared desirable to the Mannings, and it certainly created a financial liability when he died.

Elizabeth countered her family's disparagement with a marked commitment to her Hathorne identity, expressed most tellingly in the bosom of the Manning family after her husband's death.[8] The disputes about her grief for Nathaniel—what Elizabeth Peabody termed "her all but Hindoo self-devotion to the manes of her husband" (Pearson, 267)—began during the lifetimes of those immediately involved and has been continued in twentieth-century scholarship. Although the vision of Elizabeth and her children as paralyzed with sorrow has on occasion been overdrawn, the long-term effects of bereavement may run deep in the lives of people who are not markedly gloomy. Elizabeth's clinging to the memory of her husband redoubled the assertion she had made in marrying him; she formed a pattern of life that insisted on her refinement, at odds with the mercenary scramble of the Manning household.