Chenchus

During the Palæolithic Age, the vast forests and park-lands of South India were inhabited by bands of nomadic people, who lived by hunting and the gathering of wild fruits, tubers, and edible roots. The only traces left by these early foodgatherers are crude stone implements found on the surface of many parts of the Deccan; so far no skeletal remains of the early races have come to light. Yet, in some isolated parts of the subcontinent, small groups of aboriginals persisted until modern times in a way of life which outwardly had changed very little since the Stone Age.

The Chenchus of Andhra Pradesh are one of these ethnic splinter groups, which were left behind by the material advance of the great majority of the South Indian population. Their present habitat is confined to the rocky hills and forested plateaux of the Nallamalai Range, extending on both sides of the Krishna River. Until 1947 this river formed the border between the princely state of Hyderabad, officially known as His Exalted Highness the Nizam's Dominions, and the Madras Presidency of British India. At that time Chenchus were found both in Hyderabad and in British territories, but today their entire habitat lies within the state of Andhra Pradesh, which contains the overwhelming majority of the speakers of the Dravidian tongue of Telugu, the language spoken also by the Chenchus.

Although in the census of 1971 more than 18,000 Chenchus were enumerated, only a few hundred persist today in their traditional life-style as semi-nomadic forest dwellers, and it is with the latter that we are mainly concerned in the context of this study.

In their physical make-up the Chenchus conform largely to a racial type described by anthropologists as Veddoid, a term derived from the Veddas, a primitive tribe of Sri Lanka (Ceylon). Like the Veddas, the

Chenchus are of short and slender stature with very dark skin, wavy or curly hair, broad faces, flat noses, and a trace of prognathism. Though no longer dressing in leaves like their ancestors, of whom the seventeenth-century Muslim chronicler Ferishta gave a poignant description, they normally wear but the scantiest dress: the men small aprons suspended from a fibre or leather belt, the end drawn in between the legs, and the women cotton bodices and a length of sari-cloth wound round their hips. There is no people in India poorer in material possessions than the Jungle Chenchus; bows and arrows, a knife, an axe, a digging stick, some pots and baskets, and a few tattered rags constitute many a Chenchu's entire belongings. He usually owns a thatched hut in one of the small settlements where he lives during the monsoon rains and in the cold weather. But in the hot season communities split up and individual family groups camp in the open, under overhanging rocks or in temporary leaf-shelters.

The basic unit of Chenchu society is the nuclear family, consisting of a man, his wife, and their children. For all practical purposes husband and wife are partners with equal rights, and this equality of status means that the family may live with either the husband's or the wife's tribal group. Each such group holds hereditary rights to a tract of land, and within its boundaries its members are free to hunt and collect edible roots and tubers. These used to be the Chenchus' staple food, though we shall see that in recent years there has been a change in their diet and ways of subsistence.

The Chenchus are characterized by a strong sense of independence and personal freedom. None of them feels bound to any particular locality, and the ability to move from one group to the other allows men and women to choose the companions with whom they wish to share their daily lives. Marriage rules are based on the exogamy of patrilineal clans. As long as they observe the rules of clan exogamy young people are free to marry whomsoever they wish. Spouses can separate without any formality, but the abduction of a woman still living with her husband is disapproved of as immoral.

In the sphere of religion the Chenchus evince certain characteristic traits which distinguish them from the surrounding Hindu peasantry. Though they worship some of the deities prominent in the cult of Telugu villagers, they accord much greater importance to a powerful goddess who has control over the game and the fruits of the forest. They also revere a sky god who shares some features, including name, with the Hindu supreme divinity Bhagavan and, though not believed to intervene very much in human affairs, is credited with power over life and death. The Chenchus' ideas of man's fate after death are vague, and it would seem that various notions adopted from their Hindu neighbours have not been incorporated into a consistent body

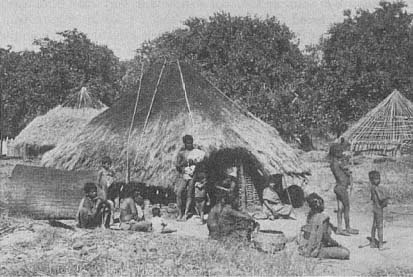

The Chenchu settlement of Pulajelma in 1940; during the dry winter season

the round huts with conical roofs are being rethatched. In the background is

the framework of a hut under construction.

of eschatological beliefs. There is no definite idea that a person's fate in the hereafter depends on his deeds in this life, even though some Chenchu stories contain references to reincarnation. More widespread is the belief that a person's life-force (jiv ) is derived from the supreme god and returns to him after death. The whole concept of a life-force, a belief common to various Indian populations, very likely stems from casual contacts with Hindus, and thus represents a comparatively new element in Chenchu thinking.

Until two or three generations ago, the Jungle Chenchus seem to have persisted in a life-style similar to that of the most archaic Indian tribal populations, and their traditional economy can hardly have been very different from that of forest dwellers of earlier ages. In the following chapters we shall see that, despite recent developments and innovations, the Chenchus still stand out from all the other tribal populations of Andhra Pradesh.

In other parts of India, however, there are still some comparable groups of foodgatherers who have so far resisted the pressure to move out of the forests and change over to a more settled life. Several of these tribes inhabit the forested hills of the Southwest Indian state of Kerala. Anthropologists have studied the Kadars, who form the subject of a book by U. R. von Ehrenfels, and the Malapantaram, also known

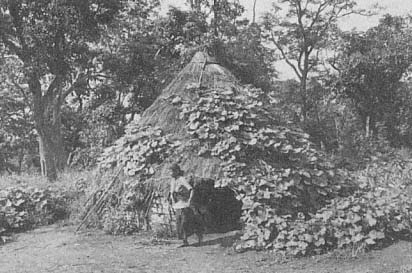

A hut in the Chenchu settlement of Boramacheruvu in 1978. There has been

no change in the structure of huts, but Chenchus have learned to grow

marrows and to train them up the roofs of their huts.

as Hill Pantaram, whom I visited in 1953 and who were subsequently investigated in depth by Brian Morris. Of special interest are the parallels between the Chenchus and the Veddas of Sri Lanka, the first South Asian tribe of hunters and foodgatherers to arouse the interest of western scholars, notably C. G. Seligmann and P. Sarasin. The Veddas have virtually given up their traditional life-style, but during some brief encounters with groups of semi-settled Veddas I was struck by a physical similarity between Veddas and Chenchus so close that it would be exceedingly difficult to distinguish members of the two populations if brought together in one place. Though separated by a distance of hundreds of miles and a stretch of sea, the two groups may well be remnants of the most archaic human stratum of South Asia.

Bibliography

Ehrenfels, U. R. von. The Kadar of Cochin. Madras, 1952.

Fürer-Haimendorf, C. von. The Chenchus--Jungle Folk of the Deccan. London, 1943.

——. "Tribal Populations of Hyderabad: Yesterday and Today." Census of India, 1941. Vol. 21. Hyderabad, 1945.

——. "Notes on the Malapantaram of Travancore." Bulletin of the In-

Chenchu drawing his bow. Hunting used to be an important activity of the men,

and though game has been depleted Chenchus are still in the habit of carrying

bows and iron-tipped arrows.

ternational Committee on Urgent Anthropological and Ethnological Research , no. 3 (1960), pp. 45-51.

Morris, Brian. "Tappers, Trappers and the Hill Pantaram." Anthropos 72 (1977): 225-41.

Seligmann, C. G., and Brenda. The Veddas , Cambridge, 1911.

Sarasin, Paul und Fritz. Die Weddas von Ceylon und die sie umgebenden Völkerschaften. Wiesbaden, 1893.

Scott, Jonathan. Ferishta's History of Dekkan. Shrewsbury, 1794.