2—

The Cultic Roots of Culture

Eugene Halton

. . . man, proud man,

Drest in a little brief authority,

Most ignorant of what he's most assur'd,

His glassy essence, like an angry ape,

Plays such fantastic tricks before high heaven

As makes the angels weep.

—Shakespeare, Measure for Measure, act 2, scene 2

"Sleep-pictures"

—New word coined in sign language by an ape to describe what it did at night.

A little knowledge is indeed a dangerous thing. No age proves it more than ours. Monkey chatter is at last the most disastrous of all things.

—D. H. Lawrence, Etruscan Places

What is culture? The usual way of answering this question is to trace the modern history of the "culture concept" from E. B. Tylor to the present. Such a history can be quite revealing, because the culture concept itself is a cultural indicator of the major intellectual tendencies and battles over the past century. The joint statement in 1958 by A. L. Kroeber and Talcott Parsons on culture formalized a kind of a truce between structural functionalism and cultural anthropology,

ratified by the two leading proponents of each camp (some may have regarded it as what in business is called a "hostile takeover attempt" of the culture concept by Parsons, although "corporate merger" might be a more apt expression).

The culture concept, now a hotly contested topic for sociologists (as perhaps signified by the theme of this book), remains a profound indicator of contemporary intellectual culture. Although academic sociology has finally seemed to acknowledge the importance of culture, as seen in the recent creation of cultural sociology sections of the German and American sociological associations in the past few years, this does not at all ensure that the concern with culture will animate new directions for theory. The very term culture is so indeterminate that it can easily be filled in with whatever preconceptions a theorist brings to it.

Indeed, the sociology of the new culture section in the American association suggests that the objectivist and positivist prejudices of mainstream American sociology are appropriating the "soft" concept of culture by making it "hard." A peculiar irony of this development is that the objectivists share a tendency with relativists to view culture in purely conventional terms. Hence the inner social aspects of culture—subjective meanings, aesthetic qualities of works of art or common experience, the "spontaneous combustion" of new ways of feeling, doing, and conceiving—are either proclaimed to be not sociological, reduced to external considerations, or are virtually ignored. The outer aspects, the externals of culture, such as reputations, "tool kit" strategies of action, social networks, and production standards, although admittedly social, are enlarged to cover the whole meaning of culture (for example, Becker 1982; Swidler 1986; Griswold 1987; Wuthnow 1987). The result is that culture legitimates new topics of study while simultaneously being tamed to meet the expectations of actually existing sociology: old wine comes out of new bottles, and we remain, to paraphrase Shakespeare, most ignorant of what we're most assur'd, our glassy social essence.

By beginning with a brief tour of the contemporary landscape of culture theory, I hope to show how current conceptions of meaning and culture tend toward extreme forms of abstraction and disembodiment, indicating an alienation from the original, earthy meaning of the word culture , I will then turn to the earlier meanings of the word and why the "cultic," the living impulse to meaning, was and remains essential to a conception of culture as semiosis or sign-action. Putting the "cult" back in culture requires a reconception of the relations between human biol-

ogy and meaning, and I touch on this by looking at dreaming as a borderland between biology and culture, a thoroughly social, yet private, experience. Dreaming not only highlights the cultic roots of culture—the spontaneous impulse to meaning—but also illustrates one way in which the technics of the biosocial human body forms the primary source of culture. Sociologists have seldom considered dreaming itself, perhaps because it seems nonsocial. Yet I will attempt to show why dreaming, although private, is a thoroughly cultural, biological, communicative activity. The deepest implications of this chapter are that contemporary modern culture in general, and intellectual culture in particular, have unnecessarily narrowed our conceptions of meaning and culture and that by undertaking a broad historical reconstruction of human consciousness and communication—known in the German context as philosophical anthropology —we can see why culture seeps into our very biological constitution: cultus , the impulse to meaning.

A Report to the Academy

In Franz Kafka's "A Report to an Academy," an ape gives a lecture on his acquisition of symbolic consciousness. He describes his long months in a tiny iron cage on board the ship that brought him to occidental civilization and the unbearable loneliness that tortured him into a state of cultivation. Becoming communicative, as he put it, was his "only way out." He learned to become rational, to communicate, to drink schnapps and wine. He became socialized into a "cultural system," and, in ways quite consistent with what most contemporary theorists of culture believe, he became utterly estranged from his animal nature. Thus, when presented with a female ape mate, he could only see "the insane look of the bewildered half-broken animal in her eye," a dimwitted unconscious creature of nature, uncivilized, incapable of drinking wine, let alone schnapps.

I would like to propose Kafka's ape, this hairy biped virtually reduced to talking, as the ideal type of ethereal creature proposed by most contemporary theories of culture. This creature, regardless of whether one reads of him in structuralist, poststructuralist, or critical accounts, or in structural-functionalist and neofunctionalist ones, is a product of unfeeling systems; his or her actions thoroughly stamped with the impress of an inorganic, rational system.

The proponents of Kafka's ape usually assume that meaning is a systemic property, that signification forms a logical system, and that culture is a code for order. Even the antirationalist opposite proposed by some "postmodern" theorists, such as Jean Baudrillard, Jean-Francois Lyotard, and Jacques Derrida, remains tethered to the structuralist logic it acts out against and infected with the old Cartesian "ghost in the machine" dichotomy: the ethereal ape of deep structural code and poststructural fission, without presence; his or her body reduced to a text. When Lyotard proclaims his pseudorevolutionary postmodernism, "Let us wage a war on totality; let us be witnesses to the unpresentable; let us activate the differences and save the honor of the name," we see merely another avatar of what painter Ernst Fuchs has called the invisible dictator , a servant of the ghost in the machine mentality of modernity who happens to reside on the ethereal side of the dichotomy. If modernity is characterized as cultural nominalism (Rochberg-Halton 1986)—a dichotomous worldview that falsely divides thoughts from things, producing an ethereal conception of mind and a materialized conception of nature—then we can well understand why Lyotard suddenly waxes nostalgic to "save the honor," not of a flesh and blood creature but of "the name" itself in its abstract generality.

The same etherealizing and mechanizing tendencies reside on the other half of the great divide of cultural nominalism, for humanity incarnate is also the unacknowledged enemy of many current biologically based theories of culture, such as those of human ethology or sociobiology. The seeming antithesis to the ethereal ape of structuralism and poststructuralism, the so-called natural man of ethology and sociobiology, likewise shares a domination by the calculating character of modern rationality. Like Caliban of The Tempest , that nasty and brutish subhuman, the creature of ethology and sociobiology is all appetite and impulsive greed. Yet these Hobbesian "state of nature" emotions are themselves façades for a cunning, underlying, rational genetic choice theory. Indeed structuralism, poststructuralism, rational-choice theory, and the rational calculation imputed to the genes by sociobiology are only apparently opposed; inwardly they speak the same disembodied language. The incarnate human body, with its stored capacities of memory and tempered abilities to suffer experience and engender meaning, is epiphenomenal in the sociobiologists' accounts; all that truly matters is the ethereal rational self-interest and its total willy-nilly maximalization (Rochberg-Halton 1989a).

We see the same ethereal language, albeit in a different dialect, in

those theories that view culture as "a system of symbols and meanings," as though system were the be-all and end-all of culture and human action. Such theories claim to do justice to the systematic nature of human signification, but in reality they grossly exaggerate those aspects of signification concerning conceptual systems—as though culture were a domain of knowledge instead of a way of living—while ignoring or distorting those aspects of signification that reside outside the boundaries of rationality and systems. These latter forms of significatory experience include dreaming, imaginative projection, lived and suffered experience and its contingencies—what Charles Peirce termed iconic (or qualitative ) signs and indexical signs (signs of physicality or existence)—as well as symbolic signs that are conceived within a living context and a larger purport beyond the narrow confines of system and rationality.

In founding modern semiotics toward the end of the nineteenth century, Peirce proposed that signification occurs through three modalities of being. He demonstrated logically not only why signs can represent their objects qualitatively, existentially, and conventionally but also why all three modalities are inherently social (Rochberg-Halton 1986). His existential signs, or indexical signs, are therefore fundamentally unlike the positivist notion of semantic reference, with which they are sometimes confused. Similarly, iconic signs, in being wholly within semiosis, or sign-action, convey essences , or the qualities of their objects, within the social process of interpretation. Iconic signs may exist within social conventions, yet are not reducible to conventional signification. Both advocates and critics of essentialism tend to view essences as outside of the realm of signs, yet Peirce's concept of iconic signs undercuts both positions. Such nonconventional modalities of signification are fundamental to a vital culture and civilization, I claim, though they may fall outside the pale of conventionalist theories.

In the etherealized language of contemporary theory, the "natural" human of sociobiology and the "cultural" one of individualistic or systematic conceptualism are equally divested of organic nature and personhood. Even an ape can see that these creatures are simply lackeys of rationalism, ignorant of their "glassy essence."

Culture theory is facing the problem portrayed in the 1950s American science fiction movie, The Invasion of the Body Snatchers . In this movie the citizens of a small American city are secretly replaced gradually by alien replicas grown from pods that have fallen from outer space. When placed near a sleeping human body, the pods assume control by appropriating memory, personality characteristics, and a perfect physi-

cal resemblance; all they lack is human emotions. As the pod creature blooms in the night, the human creature withers, so that the next morning—presto!—a real vegetable substitute walks and talks in embodied form and the "system of symbols and meanings" is virtually unchanged: people still drink coffee and read the newspapers in the modern manner criticized by Camus, though fornication has become obsolete. But of course there is one major change in the culture of this town, for the system of symbols and meanings has taken on a distinctly alien life of its own, and the one passion left to the quasi-carnivorous vegetarians—if I may so describe creatures who absorb human flesh while remaining vegetables—is to transform all human life to their system of perfect, dispassionate being, to their rational system of symbols and meanings.

Now many valid interpretations of The Invasion of the Body Snatchers can be given. It could signify the paranoia of the McCarthy era in the 1950s. Or, in its remade version from the 1980s, it might signify the neo-1950s paranoia of the neo-McCarthyite neoconservatives. It could also be taken to signify the deadliness of "organization man," as a sort of collective synonym for Willy Loman of Arthur Miller's Death of a Salesman . We could also interpret this movie as a prophecy of the evisceration of the American city by the "alien" automobile and shopping mall, a process that began in earnest in the 1950s and continues unabated today, leaving in its wake "urbanoid tissue." For my purposes the movie is a popular narrative of mythic rationality: the progressive loss of natural human capacities resulting from the dictatorship of the megamachine of modernity. The cultural processes that effuse from the movie in phobic form are expressed in recent culture theories in intellectual form.

Culture theory, in its dominant contemporary manifestations, is to my poor ape eyes an old science fiction movie, practiced by would-be body snatchers: some claim to transform the body into a text or into communicative "talking heads"; still others seek to appropriate the human capacity to body forth meaning to the depersonalized system, for example, Niklas Luhmann's concept of autopoeisis . A considerable number of feminists have as their goal, not the reform of gender relations, but the eradication of gender: they take a neutered androgeny as an ideal instead of as a form of deprivation. Camus regretted modern man, reduced to a life of coffee drinking, newspaper reading, and fornicating. What would he say of our genderless, eviscerated, postmodern person, reduced to the status of a text? At least Camus's modern man could have a little coffee and sex now and then. Whether one regards gender as

limited to conventional social roles or, as I believe, an aspect of one's identity with deep biosemiotic roots in the human body, femininity and masculinity ought to be celebrated as part of what it means to be human. The attempt to eradicate gender differences is based on the mistaken assumption that genderlessness is requisite for social equality. Those who would devalue gender are unwitting accomplices of the invisible dictator of modernity, the neutered ghost in the machine.

The body has recently emerged as a major theme in intellectual life, but it is for the most part a conceptualized and etherealized body modeled on the text: the gospel of postmodernism seems to proclaim that "the flesh was made word and dwells among us!" In other words, it is not so much "body language" that is now fashionable as the body as language. The rhetoric of the body, the conventionalization of the body, and the symbolism of gender differences can all be significant topics. But when we note how little is said about the organic, biological body in these discussions, we begin to suspect that the academic megamachine is continuing its work of rational etherealization. Such is perhaps more clearly the case in Paul Ricouer's and Jacques Derrida's calls to view human action and social life as texts or in Jürgen Habermas's theory of communicative action, which says much about rational talkers talking, but very little about actors acting: felt, perceptive, imaginative, bodily experience does not fit these theories (Rochberg-Halton 1989b).

Or consider the systems theorist Niklas Luhmann, who introduced the idea of autopoeisis to account for self-generating systems. Here we see another contemporary avatar of the megamachine. The abstract, lifeless "systems" theory, because it excludes the living humans who comprise the social "system" as significant, ignores those natural capacities of life for self-making and self-generation. Autopoeisis must ignore poeisis , the human ability to create meaning in uniquely realized acts and works that transcend mere system per se. Therefore Luhmann's theory can be seen as part of the age-old dream to give life to the machine, in this case the machinelike system. His concept of autopoeisis is like the robot, android, or other automation fetishes of contemporary popular culture and movies, many of which involve (and even celebrate) a transformation of humans into automatons. Such sociological theories are not too distant from materialist artificial intelligence and "neural network" theories, which view human beings, to quote computer scientist Marvin Minsky, as highly systematic "meat machines." I take these intellectual and cultural phenomena as further signs of the capitulation of autonomous life to the automaton.

Hence the current interest in the body may have the further undoing of the body as its unacknowledged goal. Whether disembodied as conceptualism or reified as mechanistic system, we are still left with the ghost in the machine.

Contemporary culture theory is, for the most part, a form of sensory deprivation. Those who proclaim culture to be a "system of symbols and meanings" make an uncritical assumption that culture, symbols, and meanings neither touch nor are deeply touched by organic life. Indeed the ideologues of culture theory tend to regard any concern with the relations between culture and organic nature or evolution as a threat to the hegemony of the cultural system over meaning.

There are significant exceptions to this outlook, notably in the work of Clifford Geertz, Victor Turner, and Lewis Mumford (Rochberg-Halton 1989c, 1990). Geertz has written on the interaction of culture and biology in the emergence of human culture. As he says in his essay "The Growth of Culture and the Evolution of Mind": "Man's nervous system does not merely enable him to acquire culture, it positively demands that he do so if it is going to function at all. Rather than culture acting only to supplement, develop, and extend organically based capacities logically and genetically prior to it, it would seem to be ingredient to those capacities themselves. A cultureless human being would probably turn out to be not an intrinsically talented though unfulfilled ape, but a wholly mindless and consequently unworkable monstrosity" (1973:68). By implication one can also say that a natureless human being could not be considered "civilized," but a similarly unworkable monstrosity.

As the neurological disorder of autism reveals, it is possible to perform and remember complicated human tasks that are yet devoid of meaning. As cases of individuals who have suffered damage to the hippocampus reveal, it is possible to retain the heights of human consciousness, speech, and passion while trapped in a continual present, utterly devoid of the ability to remember anything since the time of the damage, to encode new information, or to project a course of action beyond the immediate situation. This misfortune tragically gives the lie to the avant-garde dream of erasing the past to achieve a "live" present: such a culture would truly be posthuman in the sense of being deprived of the means of human experience. Clearly human biology, as seen in the human brain and its meaning and memory capacities or in the vocal organs, is involved in a reciprocal relationship with culture.

Culture may be an objectified organ of meaning, but it remains

potentially connected to the organic proclivities and limitations of human bodies through the tempering effects of experience. The plasticity of culture does not signify the poverty of underlying human instincts, as Arnold Gehlen thought, but the positive plasticity or vagueness of human instincts: culture does not free us (or deprive us) of biology but has coevolved as an intrinsic aspect of human biology.

To anyone who seriously considers how human culture came to be, Geertz's statement that culture is ingredient to organically based capacities challenges the so-called nature-culture dichotomy. Ironically though, Geertz's ideas on the interaction of culture and biology are rarely cited, whereas his more conceptualistic "cultural system" works are cited. Though Geertz is generally appreciative of the significance of organic human nature for culture, even he retains the reductionistic tendencies of the "cultural systematizers" to view meaning as limited to the mode of conventional signification.

Conventionalism, the view that all human meaning is based upon non-natural social conventions, holds a pervasive sway over contemporary life. The leading French schools of thought associated with structuralism and poststructuralism retain strong influences of Ferdinand de Saussure's conventionalist semiology, and even Pierre Bourdieu's attempt to develop a more experiential category of the habitus remains thoroughly conventionalist, viewing the habitus as a "system of dispositions."

This view is particularly clear in Bourdieu's discussions of aesthetic judgment in his book Distinction, in which he assumes the standard dichotomy between "essentialist" and conventionalist analysis and claims that essentialist analysis "must fail" because it ignores the fact that all intentions and judgments are products of social conventions. The term essentialism carries with it highly negative meanings in cultural studies today, and Bourdieu's criticism of essentialism represents the tendency to regard aesthetic qualities—the essential—as nonsocial. The producer's intention

is itself the product of the social norms and conventions which combine to define the always uncertain and historically changing frontier between simple technical objects and objects d'art. . . . But the apprehension and appreciation of the work also depend on the beholder's intention, which is itself a function of the conventional norms governing the relation to the work of art in a certain historical and social situation and also of the beholder's capacity to conform to those norms, i.e., his artistic training. To break out of this circle one only has to observe that the ideal of "pure" perception of a work of art qua work of art is

the product of the enunciation and systematization of the principles of specifically aesthetic legitimacy which accompany the constituting of a relatively autonomous artistic field. The aesthetic mode of perception in the "pure" form which it has now assumed corresponds to a particular state of the mode of artistic production (Bourdieu 1984:29–30).

By claiming that all aesthetic experience is purely conventional and therefore social, Bourdieu is attacking the view that aesthetic judgment consists in an unmediated act of perception and that the work of art possesses inherent qualities unmediated by social signification. In the conventional view that Bourdieu takes, to be human is to be the enclosed product of those specific social norms in which one finds oneself. It is the same old world in which the social is limited to the conventional and modalities of nonconventional signification, such as iconic and indexical signs, are thereby falsely assumed to be nonsocial. It is a world in which the human creature, who, above all others both is open to meaning and needs meaning, is denied the social capacity to body forth genuinely new meaning not reducible to, though growing out of, prior social norms. Another route, which Bourdieu's conventionalism forbids him to take, is to view aesthetic experience as fully social, yet not necessarily conventional, so that conventions themselves are live processes of sign interpretation open to experience, growth, and cultivation or "minding." In such a view every sign can possess its own qualitative significance or essence qua communicative sign, as well as reflect social structures. Hence, from my perspective, aesthetic experience may be truly formative in giving birth to new "social norms." The ability to body forth new meaning, not reducible to prior conventions, has the added advantage of being able to explain how conventions developed in the first place, a question that conventionalism usually avoids.

Anthony Giddens and Jürgen Habermas have sought to reconstruct the basis of social theory, but both remain stalwarts of unreconstructed conventionalism at the heart of their theories of meaning. Giddens has sought to broaden the base of contemporary theory by using a French structuralist conception of structure and linking it with a theory of "agency" influenced by language analysis, ethnomethodology, and symbolic interactionism. His "structuration theory" can be seen as an attempt to deal with the old sociological problem (itself part of the older nominalist problem) of the relation of the individual with society, or "action" with "order," or subject with object. Yet even a reconstructed structuralism remains too narrow to encompass structure; while agency, even in a broad sense, remains too narrow to encompass subjectivity,

and both are inadequate for the creation of a broader theory of meaning. French structuralism reifies structure, treating it as a deep code of "logical" differences divorced from human practices, habits, and memory. "Agency" does not go deeply enough into the personal or individual side of meaning, which includes the being acted upon or suffering of experience, the "patient" side of the agent-patient dialectic, let alone the inner dimensions of experience that do not fall under the rubric of agency.

Richard Rorty, who would seem to take a very different perspective, mistakenly called neopragmatism, remains within the conventionalist fold he seems to reject, viewing meaning as limited to arbitrary language games. Unlike the pragmatists, he denies that there are qualitative and existential modalities of signification not reducible to conventional signs alone (Rochberg-Halton 1992). Surely human languages involve conventions, but the full range of meaning or human communication—not to mention human social life—is simply not exhausted by conventional signification. As the neurologist Oliver Sacks put it:

Speech—natural speech—does not consist of words alone, nor . . . "propositions" alone. It consists of utterance —an uttering-forth of one's whole meaning with one's whole being—the understanding of which involves infinitely more than mere word-recognition. . . . For though the words, the verbal constructions per se, might convey nothing [to aphasics], spoken language is normally suffused with "tone," embedded in an expressiveness which transcends the verbal—and it is precisely this expressiveness, so deep, so various, so complex, so subtle, which is perfectly preserved in aphasia, though understanding is destroyed (Sacks 1987:81).

Given the undeniable facts of communication practices in humans and other species in which signification occurs through nonconventional modalities, why then does conventionalism hold such a power over the contemporary mind?

One way to answer this question is to view these theories as emanating from cultural nominalism, a term I use to characterize the modern epoch. Cultural nominalism denotes modernity as a culture rooted in the dichotomous principles of philosophical nominalism. I do not suggest that modernity was caused by nominalism, but that the philosophy that arose in opposition to scholastic realism was itself a symptom of the shift of epochs, one that put into philosophical form the underlying antipathies of the emergent ethos. Yet it should also not be forgotten that philosophy and theology had significant influences on the development of Western civilization in the Middle Ages.

Max Weber's patently false idea that modern capitalism should be viewed as a sixteenth-century product of the Protestant ethos ignores the clear emergence of capitalism out of medieval Catholic culture and the rising nominalism that gave birth to Protestant theology. Early nominalists, following the via moderna of William of Ockham, claimed that reality could be found only in knowledge of particulars, that general laws are fictions or conventions, and that conventions are simply names for particulars, hence nominal. Nominalism in effect created two worlds by driving a wedge between thought and things and then faced the problem of how to put them together, the problem of modern philosophy. What the scholastics might have accepted on faith or revelation becomes increasingly inexplicable in the nominalist ethos. Descartes, for example, assumed a dichotomy between thinking substance and extended substance, the ghost in the machine, and faced the problem of how we can have valid knowledge of objects if the only basis for knowledge is intuitive individual self-consciousness.

What is interesting about the nominalistic ethos is how it systematically undercuts cultus —the spontaneous impulse to meaning. The whole ideal of systematic, rational science modeled on the mechanical conception of the universe that one sees in Descartes and Hobbes, who both believed that life, as Hobbes put it, "is but a motion of Limbs," grows directly out of the spirit of nominalism. By the time of Calvin, who was educated in nominalist theology, "the impulse to meaning" becomes an intolerable threat to the great clockwork system of predestination and rational self-control. Hobbes, who also was taught nominalist theology, transformed the impulse to meaning into a mythic projection of individual competitive lust and aggression in the state of nature, which had to be repressed by a social contract—a non-natural artifice or convention. Bentham psychologized and nominalized it yet further into individual sensations of pleasure and pain. Even Freud, who is instrumental in the return of the cultic in twentieth-century culture, based his metapsychology in a Bentham-like underlying "pleasure principle" of the reflex-arc concept.

One cannot deny that much of meaning is conventional, though conventions themselves, it seems to me, are inherently purposive and subject to cultivation. Conventionalism is proposed as an antidote to reductionism, yet it radically reduces the realm of significance, meaning, and the social. That which is outside the system is regarded as meaningless until it is "systematized." The conventional view says that conventions or codes encompass culture. Hence a number of recent sociologi-

cal studies take the position that art can be understood solely as social conventions, thereby denying aesthetic quality (Wolff 1981; Becker 1982; Bürger 1984; Griswold 1987). Similarly, attempts to discuss either the brute factuality or the esthetic or inherent meanings involved in human experience are frequently dismissed by cultural theorists as reductionistic or obsolete because these approaches fail to see that all meaning is conventional, that is, dependent on cultural belief systems or conventions. Hence the expressive outpouring of an artist is meaningful only insofar as it can be related to existing cultural values, beliefs, and constructions. The inner compelling expressiveness of a work of art is reduced to outer considerations.

One can view a late work by the sculptor Ivan Mestrovic[*] , An Old Father in Despair at the Death of His Son (figure 2.1), and, knowing that Mestrovic's own son committed suicide, see the autobiographical source for the agonized figure. Clearly representational conventions are involved in the form of this sculpture. But one is still left finally with the sculpture itself, the powerful father's hands covering most of the face in grief. To say that the sculpture communicates the system of artistic representation or that it is an "aesthetic-practical" form of communication (Habermas) is to miss the point that this physical thing is a bodying forth of human feeling through the hands that shaped it, directly conveying the feeling of human grief through the hands covering the agonized face. It is not a "symbol" standing for something else; it is a living icon and secretion of human experience. It may involve conventions, but these are the vessel, the husk, that contains that actualized experience.

Most sociologies of art and culture do not consider that a work of art might be a spontaneous, meaning-generating gesture or sign not reducible to the conventions from which it grew. The organic, the inherent qualitative possibilities, the imaginative, the spontaneous, the contingent, the serendipitous—in short, the extrarational and nonsystematic—must be devalued or disregarded by the practitioners of conceptual system . The result is a systematic ethereal grid that treats only the externals of culture while denying its vital, extrarational, incarnate sources.

Culture as abstract, depersonalized system denies the living source of culture as cultus . In its reliance on culture as system, it raises system from a means of interpretation to a virtual end of cultural life. Hence culture theory itself is by and large part of a progressive externalization of meaning in cultural life generally: meaning as technique, meaning as prepackaged script, meaning as "the honor of the name."

Figure 2.1.

Ivan Mestrovic[*] , An Old Father in Despair at the Death of

His Son, 1961. Snite Museum of Art, University of Notre Dame.

The Culture and Manurance of Minds

When Francis Bacon in 1605 wrote of "the culture and manurance of minds," the literal sense of culture as tending and cultivating nature was still very much in the foreground, although the metaphoric extension of the term to mind was intended. The term culture traces back to the Latin colere, which meant variously to till, cultivate, dwell or inhabit, and which in turn traces back to the Indo-European

root, *Kwel- , which meant to turn round a place, to wheel, to furrow. As Raymond Williams noted:

Some of these meanings eventually separated, though still with occasional over-lapping, in the derived nouns. Thus "inhabit" developed through colonus , Latin to colony . "Honour with worship" developed through cultus , Latin to cult. Cultura took on the main meaning of cultivation or tending, though with subsidiary medieval meanings of honour and worship. . . . Culture in all its early uses was a noun of process: the tending of something, basically crops or animals. . . . At various points in this development two crucial changes occurred: first, a degree of habituation to the metaphor, which made the sense of human tending direct; second, an extension of particular processes to a general process, which the word could abstractly carry (Williams 1976:77).

The term culture , according to Williams, was not significant as an independent noun before the eighteenth century and was not common before the nineteenth century. But even before the nineteenth century the term was already beset by the etherealizing tendencies of ethnocentric universalism, so that Johann Herder could state that "nothing is more indeterminate than this word, and nothing more deceptive than its application to all nations and periods." Colonize and culture are both derived from the same root, and Herder was well aware of how the Enlightenment dream of "universal reason" could also be used as an expression of European power. He complained of the treatment of human histories and diversities as mere manurance for European culture: "Men of all the quarters of the globe, who have perished over the ages, you have not lived solely to manure the earth with your ashes, so that at the end of time your posterity should be made happy by European culture. The very thought of a superior European culture is a blatant insult to the majesty of Nature" (1784–1791, cited in Williams 1976:79).

Cultural anthropology has in many ways taken Herder's words to heart, admitting—to use the title from one of Clifford Geertz's books—"the interpretation of cultures" in the plural as its central task. Yet in the long history and vicissitudes of the term culture , there has remained a broader sense of culture as meaning in general, which remains a central problematic of social theory even if it has lost its earthy origins. Cosmopolitans do not like the smell of Bacon's conception of "the culture and manurance of minds," preferring the intellectualistic "systems of symbols and meanings." Please do not misunderstand me, honored colleagues of the academy. I am not simply calling for an anti-intellectual, nostalgic return to farmer's wisdom, such as expressed in the following

quotient: Die Quantität der Potate ist indirekt proportional zur Intelligenskapazität ihres Kultivators! (Or, as they say in the south, Der Dümmste Bauer hat die grösste' Kartoffel!).[*] I am simply saying that we must revitalize the concept of culture and free it from the abstractionist grip of our time: we must put the cult back in culture .

We have come a long way from the earthy conception of culture as a living process of furrowing and cultivating nature within and without, of the organic admixture of growth and decay that such a conception implies, of the springing forth of tendrils of belief needing active cultivation for survival. One of the glaring holes in most contemporary conceptions of culture is the lack of attention to the birth of meanings, a lack that applies equally to the term conception . In intellectual discourse, conception connotes, almost without exception, rational beliefs and not the gestation of something new, the birth of meaning. Likewise, culture now connotes systematized meaning for most culture theorists and has lost the fertile, seminal, and gestational meanings it once carried: "the culture and manurance of minds." Both the living source and the final aim of culture, I claim, is cultus . Yet it is precisely the cultic that is so frequently occulted by contemporary culture theory.

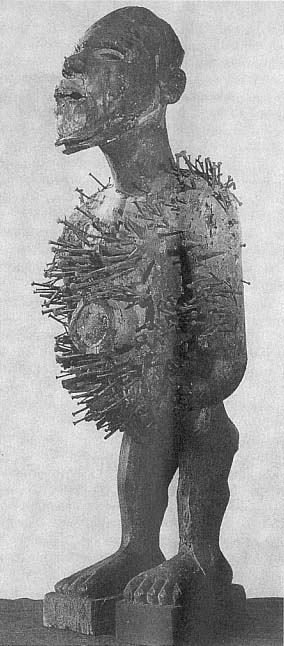

The word cult , despite its obvious relation to culture, seems worlds apart from its meaning in everyday language. Cults are usually associated with pathologically disturbed or ideologically brainwashed groups—satanists, the suicidal followers of Jim Jones at Jonestown, Moonies, and the lunatic fringe in general—but the term also applies to emerging religious sects, such as the early Christian cults. In the anthropological sense the word cult is strongly associated with ritual, as in the "cargo cults" that appeared in the South Pacific after World War II or the various rituals to Afro-Christian "saints" in the Umbanda cults of Brazil. The ethnographic record, Freud, and Durkheim have sensitized us to how certain objects become endowed with sacred or obsessional significance as fetishes—such as a wooden sculpture of a human form studded with nails by the Bakongo people of West Africa (figure 2.2). We see in these examples how deep human needs and desires seek objectified, and often fantastic or perverse, form.

One of the most insightful accounts of the cultic roots of culture is to be found in the work of Victor Turner. His masterful ethnography reveals the fundamental reality of the subjunctive mood in human affairs: the

[*] The size of the potato is indirectly proportional to the IQ of the farmer; or, the dumbest hick has the biggest spud.

Figure 2.2.

Large wooden figure studded with nails, Bakongo tribe,

Angola, nineteenth century. The University Museum,

University of Pennsylvania.

ritual process. In Turner's analyses of the Isoma and Wubwang'u rituals of the Ndembu of northwestern Zambia, one sees the fantastic interplay between human affliction and symbolic renewal, between human communities and a natural environment teeming with signification. The Ndembu are revealed to be a people with a deep appreciation of the complexity of existence and endowed with a sophisticated technics of meaning, a vast architectonic of felt, expressive forms through which they journey to those borderlands beyond human comprehensibility: death, the dead, the call of the mother-line, fecundity, transformation, the interstices of social structure. Systematizers who seek an airtight scheme with absolute closure will not find it in Turner's work. His theories are open-ended, ever acknowledging the greater richness and potentiality and not-yet-decipherable and perhaps not systematizable richness inherent in experience and culture. He continually directs our gaze instead to those social "openings" through which the ferment of culture erupts. Cultures are not simply inert structures or bloodless "systems," but form a "processual" dialectic between structure and liminality.

In his well-known essay, "Betwixt and Between: The Liminal Period in Rites of Passage" (1967:93–111), Turner attempted to grasp that virtually ungraspable mercurial element in human affairs in which normal social structure and mores of conduct are temporarily eclipsed. Liminality was that which dismembered structure in order to transform, renew, and re-member it. Turner went on to show, in this essay and in other works, how liminality provides a time of visceral or meditative (or both together) reflection, a time of reflective speculation: "Liminality here breaks, as it were, the cake of custom and enfranchises speculation. . . . Liminality is the realm of primitive hypothesis, where there is a certain freedom to juggle with the factors of existence. As in the works of Rabelais, there is a promiscuous intermingling and juxtaposing of the categories of event, experience, and knowledge, with a pedagogic intention" (1967:106). Turner notes, however, that the liberty of liminality is ritually limited in tribal societies and must give way to traditional custom and law.

In Turner's works, one continually confronts the drama and mystery of life itself in its humanly perceivable forms. The live human creture, not the dead abstract system, is the source of what he termed processual anthropology . Throughout The Ritual Process , he engages Claude Lévi-Strauss in a dialectical contrast, posing his processual anthropology against Lévi-Strauss's structuralism, while yet drawing from Lévi-Strauss's analyses that which he finds useful. In Turner, one sees that

meaning is much more than a "logical structure," because it involves powerful emotions not reducible to logic, a purposiveness not reducible to binary oppositions, "a material integument shaped by . . . life experience." In short, a processual approach views structure as a slow process, sometimes very slow indeed. Or as Turner puts it, "Structure is always ancillary to, dependent on, secreted from process" (1985:190).

Turner is very much concerned with systemic or structural questions, but he continually reminds us of the human face behind the social roles, status hierarchies, and social structures. That human face may be painted with the red and white clays of Wubwang'u , or it may be adorned with the phantasms of carnival, or it may be soberly dressed in ritual poverty, but Turner's theories, and the body of his work itself, never let us forget those deep human needs for fantastic symboling to express the fullness of being.

Central to Turner's processual anthropology and comparative symbology is the ritual symbol, which he considered the "core" unit of analysis. The symbol is the "blaze"—the mark or path—that directs us from the unknown to the known, both in the Ndembu sense of kujikijila (to blaze a trail by cutting marks or breaking or bending branches on trees) and in C. G. Jung's sense. Key to the indigenous hermeneutic of the Ndembu is the term ku-solola —"to make visible," or "to reveal"—which is the chief aim of Ndembu ritual, just as its equivalent concept of aletheia is for Hans-Georg Gadamer's hermeneutic. These Ndembu terms derive from the vocabulary of hunting cults and reveal their high ritual value. The idea of making a blaze or path through the forest also draws attention to the significance of trees for the Ndembu, not only as providing the texture of the physical environment, but also as sources of spiritual power. The associations of substances derived from trees with properties of blood and milk, or of toughness with health and fruitfulness with fertility, which Turner discusses in his description of the Isoma ritual, also reveal why he chose Baudelaire's phrase "the forest of symbols," as the title for one of his books. In his ground-breaking discussions of color symbolism in Ndembu ritual, Turner shows how the social system of classification comes into play, but he roots the social meanings of red, white, and black symbols to the experiential level of bodily fluids and substances of blood, milk and sperm, and feces.

At the time of his death Turner was fully engaged in the struggle to achieve a new synthesis—a theoretical rite of passage to a broadened vision of anthropology and social theory. A number of social theorists

have been claiming to be transforming social theory—I am thinking here of Habermas, Luhmann, Giddens, and others—but for the most part they have been replaying tired variations on old themes without ever questioning the premises of modern social theory. But in Turner's synthesis of social dramas, liminality, communitas, Deweyan and Diltheyan understandings of "experience," and neurobiological semiotics, perhaps we see the unexpected outline of a new understanding of the human creature: one which reconnects biological life and meaning, which embraces the "subjunctive" as no less fundamental a reality of human existence than the "indicative," which views the realm of the fantastic as a precious resource for continued human development rather than as a vestige of an archaic and obsolete past.

Turner is regarded as an anthropologist in the Anglo-American sense, but his late work, like that of Lewis Mumford, reveals him to be a philosophical anthropologist in the German sense as well. Turner and Mumford are no throwbacks to biological reductionism. Quite the contrary: both are master interpreters of meaning, both are original contributors to the semiotic turn of the social sciences, both are exponents of a dramaturgical understanding of human action. Yet both felt compelled, in the name of human meaning , to delve into the biological sources of signification. The liminal processes revealed in lucid detail by Turner and the broad historical account of human development and sociocultural transformation given by Mumford complement each other and illustrate how both authors share a deep appreciation of the cultic roots of culture. Their work shows the way toward undoing the etherealizing spectre that haunts the contemporary study of meaning and culture as well as its mechanico-materialist opposite in human ethology and sociobiology. At the heart of Turner's and Mumford's work is ever the incandescent human form.

To those who can no longer live within the frame of mythic rationality and its cultural nominalism, the artificial split between a mechanical nature devoid of generality and a culture reduced to human conventions devoid of tempered experience and organic roots seems a quaint relic from the bifurcated world of cultural nominalism, mythic modernity. This peculiar mindset took the rationalization of culture, the technicalization of society, and the mechanization of the universe to be a troubling, yet logical, development in occidental culture: Disenchantment is the name and cost of freedom.

Is rationalization ultimately the proper term for Weber's project? Or does rational maximization better capture the processes that Weber

thought he saw inherent in religion and in the peculiar developments of the Occident?

Rationalization ought to describe the normal growth and context of rationality in human life, the place of rational capacities as organs of a mind deeper and broader than rationality alone. The human mind, in both its individual and collective manifestations, reveals the extrarational capacities of memory and invention, interpretative "sensing" and organic balancing, rich emotional communication—not at all limited to what words alone can say—and an obsessive need for the semblance of meaning.

The fullness of the human body also reveals dark, destructive impulses potentially active in all of the human capacities, impulses generated no doubt from our own animal depths but by no means excluded from our rational heights: for every Caliban there is also one of Kafka's devitalized rational apes. The rationalist too frequently places the blame for human evil and folly on the irrational, ignoring the great tendencies of decontextualized rationality toward self-destruction. "The devil made me do it" alibi only works when one fully acknowledges the ever-present devil within: criticism must always invoke self-criticism. There is in pure rationality a profound aptitude for cold-blooded murderousness and its seeming opposite: Weltschmaltz, the self-beautifying lie of sentimentalism. Albert Speer said that Hitler in his more manic moods and rages would discuss plans he did not necessarily mean to carry out. But when he was calm, cool, and collected—"rational"—his inner circle knew he fully intended to carry out his calculations, no matter how extreme. In Speer's account one sees what is perhaps the twentieth century's most notable "achievement": rational madness.

Though mythic rationality saw the many distortions that entered into modern life through capitalism, rationalism, technicalism, and individualism, it never questioned whether the mechanization of nature in the seventeenth century might also be part of this distorting process. Because virtually all of social theory has grown out of the same processes of cultural nominalism, theorists tend to accept uncritically the reified split between thought and things, between culture and nature. Culture can then be assumed to be free from nature or to seek as its goal to escape from nature through the perfection of rationality. In both cases the underlying task is to etherealize the human creature, to divest it of its organic, cultic, biosemiotic roots. Yet all the inner autonomous forms of culture, all the outer technical codes and know-how, and all the rational justifications for progressive, modernized, "communicative"

culture remain insufficient for a truly vital culture when disconnected from the tissues of life, from human bodies and their social relations.

The cultic is the springing forth of the impulse to meaning, which culminates in belief. As such the cultic is no throwback to "vitalism" but involves the deepest emotional, preconscious, and even instinctive capacities of the human body for semiosis. Although most theories of culture tend to view meaning as conventional knowledge or system, I am proposing that the essence of meaning resides in bodies sign-practices that circumscribe mere knowledge. Conventions of language, gesture, image, and artifact should be viewed as the means toward incarnate sign-practices, not as the structural or systemic foundations or ends of meaning. The very attempts to ground meaning in a theory of pure conventionalism are signs of the evisceration of meaning, the hollowing out of living human experience to the external technique or the idolatry of the "code."

By "incarnate sign-practices" I mean that culture is a process of semiosis, or sign-action, intrinsically involving the capacities of the human body for memory, communication, and imaginative projection, and is not completely separable from those capacities. Social structure, in this perspective, cannot be severed from the living inferential metaboly of human experience through systematic or structuralist abstraction, but it needs to be conceived in some relation to lived human experience and its requirements, limitations, and possibilities. Human life, in its organic fullness, remains the yardstick for social theory and cultural meaning, and neither the abstractionist distortions and perversions of the life-concept through biological reductionism nor the equally abstractionist repression of the life-concept through cultural reductionism will suffice any longer.

Dreams As Organs of Meaning

Let us turn to the social fact of dreaming, a nightly experience shared by all human beings, as an unexpected way to explore the cultic roots of culture. To most social theorists, dreams emanate from a twilight zone of questionable value: dreams are "imaginary" and therefore unimportant aspects of modern life. The task of modern social theory, after all, is to wake humanity from its dream and bring it to self-consciousness. Yet dreams, I claim, cannot be wished away from our

evolutionary past, from our sociocultural present, or from our potential futures. There is good reason to suspect that dreaming was a significant component of the experiential world of the protohumans: the fantastic image-making process, autonomously produced by the psyche, a private, though social, self-dialogue of the organism, its "language" fashioned from the forms of experience. Dreaming may very well have helped to "image" us into humanity. And we may yet remain creatures of the dream.

Sociologists might take the view that dreaming is nonsocial and therefore unsuitable for sociological analysis, except perhaps as dreams are somehow recorded and become social "texts." This sociological view remains insufficiently social, however, in not acknowledging how actual dreaming itself, like speaking, is both a social trait of all humans and consists of narrativelike structures and a "language" of images incorporated from cultural experience. Whereas speech communicates publicly shared meanings, dreams can incorporate private meanings that transcend local culture. For this reason it is important to view dreams as private, yet thoroughly social, experiences. Dreams are self-communications, feelings that have already been elaborated into communicative, imagistic signs. Dreams may be indicators not only of individual development but also of formative experiences in the inner growth of the person and the origins of human symbolic activity.

In attempting to fathom the vanished past from visible remains, we tend to ignore the most perfect archaeological artifact of human evolution: the living human body. Although archaeologists have become quite sophisticated in using medical and physical evidence from ancient corpses, they have not been as willing to use the living human body today as evidence for prior likely evolutionary developments. Yet archaeoneurology remains an area of potentially great significance, not only for an understanding of how humans became human, but also for understanding contemporary human nature and signification.

Though I am not familiar with earlier uses of the term archaeoneurology, the idea was familiar to Sigmund Freud, the neurologist and archaeologist of the psyche and amateur archaeologist of ancient civilizations. If anti-Semitism had not barred Freud from an academic career, he might have become a noted archaeologist instead of the founder of psychoanalysis. Yet Freud's investigations of the unconscious show that he remained a psychic archaeologist, attempting to show how the dreams of his turn-of-the-century patients revealed both a personal history and a biological drama as old as the human race. In The Interpreta-

tion of Dreams, Freud uses a stratigraphic method of symbol interpretation in which the contents of dreams are shown to reveal underlying sexual and familial themes, such as the Oedipal myth, and these themes are ultimately rooted in Freud's nineteenth-century neurological understanding of the reflex-arc concept. The layers of the unconscious are like the layers of time embedded in an archaeological site: each level a farther step into the past, until one arrives at the mechanical model of the reflex arc as explanation.

Freud's archaeoneurology is a curious blend of literary interpretation and scientistic mechanism. Freud posits a divided psyche, which is a classic example of cultural nominalism: there is the subject whose question is "How do I know?" and the object whose question is "How does it work?" The first Freud called das Ich, the I or ego, the second he called das Es, the it or id. The id is the realm of mechanical force, the ego is the realm of symbolic purpose. One might also read the id as Thomas Hobbes's "state of nature" and the ego as a kind of "social contract." Symbolic representation is achieved through the successful resolution of the Oedipal conflict, in which the metaphoric Oedipus in us all comes to harness the inner "natural" urges to murder and to commit incest by identifying symbolically with the same sex parent and thereby "having" or relating symbolically, rather than genitally, to the opposite sex parent. One establishes an inner triadic, psychic family representation, which serves to mediate the subject to the object, the unconscious.

One of Freud's positive achievements was to show the power of the human family in the psyche. Just as Feuerbach had unmasked the "holy family" as standing for the earthly family and Marx had unmasked the earthly family to reveal the bourgeois family, Freud attempted to show that the earthly family was itself a surface manifestation of deeper and darker forces of the unconscious. Yet his choice of the Oedipus myth and his own myth of a "primal horde," which had collectively killed the primal father and then banded together to form a social contract against further killings, have come to look much more, with the passage of time and the accumulation of archaeological evidence, like the fin-de-siècle fictions they were, when all of Europe, and Vienna in particular, banded together to kill off the past. Freud's "primal horde," perhaps more than his other images, reveals the workings of a mythic nominalism, of a world of convention banded together for its own protection and set utterly apart from its own ground of development: competitive struggle for individual survival is natural, relationship or mutual aid is not and must therefore be invented.

One sees in Freud's psychoanalytic theories the deep imprint of Hobbes and other English thinkers admired by Freud, such as John Stuart Mill, transposed to the "innerness" of German/Austrian thought. Freud helped to open up the floodgates of the unconscious in the face of twentieth-century rationalism, yet his view of the workings of the psyche is itself another manifestation of that rationalism: it is tethered to an outmoded mechanical model of biology and to a conception of human communities and communication as epiphenomenal aspects of consciousness, superimposed on the underlying reality of the id.

Freud's junior colleague, C. G. Jung, broke with him because of Freud's rationalism. Jung increasingly appreciated the purposeful role of nonrational symbols and the limited place of rationality in the purposeful activities of the psyche. One might say that whereas Freud's unconscious becomes darker the farther one penetrates into the unconscious, Jung's unconscious becomes increasingly luminous, perhaps too much so. One moves from the darkness of the personal unconscious to the archetypal figures of the collective unconscious. Jung believed that the deepest processes of the unconscious were collective, purposive symbols: literally personalities. The images of the trickster and the hero were not solely the products of legends and myths, but were realities embodied within the psyche. These personalities were related through narrative inner transformations that could be observed in dreams, in artistic activities, and, Jung believed, in the symbolism of myths and religions.

In many ways Jung comes closer to the idea of archaeoneurology, but he remained, as did Freud, bound by an overly inner view of the human psyche and too ready to deprive experience of its own formative influence in the generation and meaning of symbols. Freud and Jung opened new dimensions for the human sciences, but their theories give short shrift to the thoroughly social nature of dreaming and psychic life in general. Freud's metapsychological foundations are rooted in the nominalistic individualism of Hobbes, with symbolic consciousness the inner psychic equivalent of Hobbes's social contract, erected over the "Warre of Each against all" of the state of nature, or, in Freud's term, the id. Jung's concept of the archetypal unconscious is more social than Freud's, but it still is based on a Kantian-like structuralism that does not explain how archetypal structures came about or how human experience and culture may transcend archetypal imperatives both individually and institutionally. Sociologists may see in Durkheim's theory of conscience collective a more socially based understanding of dreams. In his late work Durkheim

attempted to show how the faculties of knowing are social, as opposed to the individual faculty theory of knowledge deriving from Kant. Yet Durkheim, too, remained tethered to the legacy of Kantian structuralism, in believing that: (1) a fundamental duality between individual consciousness and collective consciousness exists; (2) collective representations ultimately represent one fundamental, underlying, unchanging entity: society; and (3) collective representations are essentially conventional. These beliefs reveal why Durkheim remains inadequate to understand the social reality of dreaming. As opposed to Durkheim's claims: (1) individual consciousness is a social precipitate continuous with the collective biosocial heritage rather than dualistically opposed to it; (2) that which collective representations signify may emerge, grow, die, and undergo genuine transformation in time; and, finally, (3) as dream-symbols make abundantly clear, collective representations are not limited to purely conventional signification, but they draw from other modalities of signification, such as iconic and indexical signs.

The evolution of humans is marked by various anatomical changes, such as the development of the upright stance, the radical enlargement of the cranium and specifically the forebrain, and the creation of a vocal cavity with lowered larynx and subtle tongue and lip movements capable of producing an enormous variety of utterances. Speech is clearly one achievement of this process that uniquely identifies us as humans. But so too, for that matter, is artistic expression. Both are sign-practices dependent on the achievement of symbolic representation, and both reveal how to be human is to be a living, feeling, communicative symbol. Now a symbol, in the Peircean view I have adopted, is a social fact: a triadic relation whose meaning "depends either upon a convention, a habit, or a natural disposition of its interpretant or of the field of its interpretant" (Peirce 1958:8.335). In the case of the symbolic sign, as distinguished from iconic or indexical signs, the process of interpretation comes to the foreground, and, from a cultural perspective, this is to say that to be human is to be an interpreter. The very achievement of symbolic signification stands upon the vast capacities for pre- and protosymbolic communication developed by our forerunners and tempered into our physical organisms. And dreams may very well have provided the inner drama necessary to provoke us into interpretation by presenting images of a phantasmagoric "here and now," which break into the habits of everyday life.

The neurophysiology of dreaming suggests that dreaming is the inner life of humanity in a virtually purified state: the inner conversation

of brain and mind. Brain "speaks" its ancient voices of phylogenetic experience through neurotransmitters that either emanate from the old "reptilian" brain and flow upward to the cortex, where visual, associative, and motor areas are excited (Hobson 1987:338–340), or, in the view of other researchers, through a reciprocal activation of the "old" brain centers with the "new," upper ones. In this process ancient neurophysical impulses become transformed into acts and associated meanings expressed in the images—whether visual or not—themselves. Iconic signification, which is to say the inherent presence or the communicative character of the sign itself, is the predominant language of this inner world, the meeting place of brain and mind. Yet, in contemporary humans, those icons of dreams are themselves frequently shaped from the reservoir of cultural experience and symbolic signification. The resources of mind and memory, incorporating both collective cultural experience, such as language, and personal experience play an active role in either consummating or frustrating the neurochemical dance.

Dreaming is the cultic ground of mind, a communicative activity between the most sensitive archive of the enregistered experience of life on the earth, the brain, and the most plastic medium for the discovery and practice of meaning, the mind or culture. Most explanations of dreaming have tended to view it as ultimately passive, as a compensatory mechanism for daytime existence. In the Freudian view dreaming is the way that repressed wishes of the unconscious can be actively disguised through symbolism, thereby "venting" their energies in a way that will not undo consciousness. In many recent neurophysiological views, dreaming allows the recharging of the brain's neurochemical batteries. If human bodies were simply machines, these theories would perhaps be adequate. But it is important to realize that just as the mind is formative, generating new ideas collectively and individually, the brain, as the chief organ of mind, may also be formative or active.

One wonders what the neurophysiologists' answers to other human activities might be: Why do we make music, images, and dance? Why does belief play such a central role in human affairs? Why can dreams wreak such havoc upon habituated experience and memory through fantastic associations or inversions? Why are all humans compelled to participate in these strange cults of the night? Why are such bizarre antics—the nightly Mad Hatter's party of REM sleep to which all are invited whether we remember it or not—absolutely necessary to our ability to function in the day world? When we begin to ask questions such as these, it becomes possible to turn the dream question around. In

other words, only by exploring that strange culture within us in its own terms, taking the "native's" point of view toward our inner life, can we begin to understand the alien within and our glassy essence.

Perhaps dreaming itself is the purpose of dreaming, the end for which the neurophysiology is the means. As Milan Kundera writes in The Unbearable Lightness of Being, "Dreaming is not merely an act of communication (or coded communication, if you like); it is also an aesthetic activity, a game of the imagination, a game that is a value in itself. Our dreams prove that to imagine—to dream about things that have not happened—is among mankind's deepest needs." This interpretation may strike the reductionists among neurophysiologists and social theorists as too fantastic, but perhaps the fantastic is an inbuilt aspect of evolutionary reality, difficult though it may be to understand in our utilitarian age.

Although it is frequently acknowledged that the unconscious is the source of creativity, it may be that dreaming, the night music of the soul, may also help generate new neural pathways. In other words, dream images may function as prospective symbols for mind, just as REM neural activity may function as neural network-making for brain: perhaps the two work in psychophysical relation, as might be indicated by the large proportion of time devoted to REM sleep in fetuses and infants, when the brain itself is rapidly growing.

Lewis Mumford proposes that man's inner world "must often have been far more threatening and far less comprehensible than his outer world, as indeed it still is; and his first task was not to shape tools for controlling the environment, but to shape instruments even more powerful and compelling in order to control himself, above all, his unconscious. The invention and perfection of these instruments—rituals, symbols, words, images, standard modes of behavior (mores)—was, I hope to establish, the principal occupation of early man, more necessary to survival than tool-making, and far more essential to his later development" (Mumford 1967:51).

Although humanity has become increasingly conscious of itself, it has never stopped dreaming. Nor have its dreams become any less wondrous and terrifying. Communicative signs, not utilitarian tools, were the first human technics, created out of the human body itself, which was then and remains today the most sophisticated human achievement.

If we consider then the influence of dreaming as creating a movement toward interpretative order, we can see how that process could

lead to an excess of order. When stretched beyond organic limits, such as life-purposes, local habitat, and local social organization, the tendency toward interpretation could take on a life of its own. Archaeological evidence suggests that proto- and early humans lived for the most part in environments that could localize and thereby neutralize the tendency to overreach for order or system. If we think of early cities and emergent civilizations as going beyond the earlier environmental resources and limits, we can suggest that the "megamachine"—reified, centralized order—was a product of that time, as Mumford claims, but that it was also a latent possibility already built into the human creature as a negative consequence of the dream-induced body technics.

Biological evolution and cultural development are not simply a progressive casting off of shackles and a movement toward a greater and ultimately unrestrained freedom, but they involve trade-offs of one kind of limitation for another. The achievement of human symbolic consciousness may have cost us a somewhat diminished perceptual or emotional life: who is to say that the forms of feeling produced by Neanderthal burial rituals, and the dawning significance of death and mortality for Homo erectus and even earlier creatures, may not have more to do with the real essence of human symbolic consciousness than a modern rationalist treatise on culture produced by a human product of that consciousness? On the other hand, the Mozart and the Verdi Requiem provide ample evidence that the achievement of symbolic consciousness also enlarges and enhances perceptive and emotional capacities. There may have been a trade-off of emotive brain power in the overall reduction of brain size from earlier humans, such as Neanderthal, to Homo sapiens sapiens, but the subtilizing of brain through the enlargement of the forebrain may have provided compensation. One is reminded of Herman Melville's dictum: "Why then do you try to 'enlarge' your mind? Subtilize it."

Mumford and only a very few other social theorists point to the unusual fact that our big brains seem possessed of excess energies and that this characteristic may explain a number of peculiar features of human existence. But there is an even more fundamental question that seems to me ignored, even though it goes to the crux of the evolutionary debate dating back to Darwin and Wallace: How did our big brains come about? It is not simply that we had big brains which we then had to control, but also that we evolved big brains, presumably through an evolutionary increase of brain use and adaptiveness. What was it that made big brains adaptive? Increasingly complex social organization?

Increasingly complex dreaming? Or both? Did the human brain evolve in the context of an evolving mind? Did mind, and not simply chance variation or adaptiveness, need more brains? Did the emergent symbolic consciousness need more forebrain and therefore "select" for the growth of this region?

Is it possible that the idea of the megamachine goes back much farther again, back to the emergence of Homo sapiens sapiens? If protohumans evolved the tools of ritual, speech, artistic expression, and mores of conduct as means of controlling the inner anxieties, anxieties related to our big brains, perhaps the tendency to automatonlike order was also embedded in the central nervous system. Hence we would be creatures biologically impelled toward autonomy and meaning, as Mumford says, yet also biologically constructed to take the quest for meaning too far, thereby substituting order for meaning. The acquisition of meaning and autonomy may have been achieved at the cost of repetition compulsions or even the removal of biological inhibitions against overcentralization. Though cultural reductionists claim that human culture helped free us entirely from instincts, this view overlooks the possibility that human instincts continue to operate in vague and suggestive, yet vitally important, ways. Largely liberated from the genius of instinctive determination, we may be creatures neurologically constituted to walk the knife-edge between autonomy and the automaton, our task being, not to escape biology, but to make human autonomy instinctive.

Or let me express this view in another way. Perhaps the symbol itself, as the medium of human consciousness, is so constituted, both in its freedom grounded in human conventions and in its mysterious relations to the central nervous system, that it needs to be connected to perceptive and critical—that is, lived—experience. Contrary to celebrated views of the symbol (or sign in Saussure's terminology) as completely "unmotivated" or arbitrary, I claim the symbol is that sign most dependent on vital and critical experience for its continued development.

We live in signs and they live through us, in a reciprocal process of cultivation that I have elsewhere termed critical animism . If most tribal peoples have traditionally lived in a world of personified forces—or animism—and if this general outlook was evicted by the modern "enlightened" view of critical rationality and its "disenchanted" worldview, then I am proposing a new form of re-enchantment, or marriage, of these opposites. Critical animism suggests that rational sign-practices, though necessary to contemporary complex culture and human free-

dom, do not exhaust the "critical" and that the human impulse to meaning springs from extrarational and acritical sources of bodily social intelligence.

The evolution of protohumans, though marked by the greater reliance on symbolic intelligence, did not necessarily mean the complete loss of instinctive intelligence as some theorists, such as Gehlen, have implied. On the contrary, one key aspect of the emerging symbolic intelligence "in the dreamtime long ago" may very well have been an instinctive, yet highly plastic or generalized, ability to listen to and learn from the rich instinctual intelligence of the surrounding environment. The close observation of birds, not only as prey but also as sources of delight, could also help to inform one of an approaching cold spell or severe winter.

A better example might be the empathic relations to animals and natural phenomena shared by many tribal peoples. One frequently sees an identification with an animal or plant related to the practices of a people, such as the cult of the whale for fishing peoples, and a choice of an object that somehow symbolizes a central belief of a people, such as the white mudyi tree as a symbol of the milk of the matrilineally rooted Ndembu of Africa. There exists then a range from a practical, informing relationship to nature, or a fantastic elaboration of that relationship, to a purely symbolic relationship to the environment that either may be unrelated to the surrounding instinctual intelligence or that might even function as a kind of veil to obscure the informing properties of the environment. These relationships were crucial to the emergence of humankind: the deeply felt relationship to the organic, variegated biosphere, which was manifest in those natural signs or instincts of other species, and the corresponding pull away from the certainties of instinctual intelligence toward belief, toward humanly produced symbols that created a new order of reality, and in doing so, both amplified and layered over the voices of nature.

Through mimesis, emerging humankind could become a plant or bird or reindeer, and thereby attune itself to the cycles of nature through the perceptions of these beings. A mimetic understanding also involves the generalizing of nature into symbolic form. A man dressed as a raven or bear at the head of a Kwakiutl fishing boat and the lionheaded human figurine found in Germany that dates back thirty-two thousand years (a very early find possibly suggesting interaction between Neanderthals and anatomically modern humans) signify the sym-

bolic incorporation of animal qualities into human activities and provoke human reflection, through what William James called the "law of dissociation," on the meaning of human activities.

Dreaming is central to mimesis, and dreaming itself may be seen as an in-built form of "recombinant mimetics"—with all the power and danger of recombinant genetics—in which fantastic juxtapositions of neural pathways and cultural images and associations take place. Dreaming is perhaps the primal "rite of passage," through cult, to culture.

In examining the brain-mind dialogue of dreaming we see a domain that bridges nature and culture, which may have been essential to the emergence of human symbolic culture and may remain essential to its continued development. In that sense dreaming opens an unexpected window onto the cultic roots of culture: the spontaneous springing forth of belief. And if Mumford is correct that dreaming may have impelled us toward a technics of symbolism both to control the anxieties produced by the inner world and to be animated by its imagemaking powers, then perhaps we can better understand the cultic origins of culture through examining the ritual symbol itself and the drama of communication that emerged from it. I cannot undertake that analysis here. But in indicating the line we big-brained apes must have followed in entering and establishing the human world, one conceivable consequence has, I hope, become somewhat clearer. The impulse to meaning is both original to our nature and ineradicable.