Chapter Five—

Health and Social Revolution

Of the multiple forces that dictated the nature of producing and marketing oil in Mexico — markets, technology, foreign capital, diplomats, politicians, and military chiefs — the one most often neglected is the worker. What better case exists to ascertain how labor fared before the juggernaut of capitalism if not Tampico and the Golden Lane during the Great Mexican Oil Boom? Contemporaries contended that approximately 90 percent of the work force at Tampico was employed by foreigners, 70 percent by the Americans alone.[1] If capitalism molded the workers into a gray mass of dependent wage-earning proletarians anywhere in Mexico, it would be in Tampico. Here the owners controlled the labor market. Few protective laws enabled local politicos to inspect and regulate the employers. In addition, local government was weakened considerably by the continued political and military turmoil of the Revolution. A long line of military chieftains governed Tampico, most of the time with an eye toward their own survival. Was it not possible for these captains of industry, therefore, to shape the laborers in their own image: hardworking, frugal, dependent, servile, grateful, and obsequious? In short, did not the Tampico workers become a proletarianized class of semiskilled industrial workers, so dependent upon wage work for subsistence that they willingly sacrificed their labor power, at ever decreasing wages, to the owners' profits? If this could have happened anywhere in Mexico, it should have happened in Tampico.

Labor also figures in the outcome of the Revolution. Of late, some historians have tended to reduce the Mexican Revolution to a mere

rebellion, because the foreign interests, in alliance with political elites, effectively subverted and "co-opted" demands for land and labor reforms. The word co-optation is crucial. Co-optation has come to mean the active deflation of popular demands by the adoption of token reforms and the absorption of popular leaders into the patronage system.[2] Elemental to this view of the Revolution is the assumption that the demands of Mexican peasants and workers between 1910 and 1920 were indeed revolutionary. That is, the popular classes had demanded not only the destruction of the old order, the creation of a revolutionary state, and a redistribution of property (all of which did occur) but also the conversion of the economy from capitalism to socialism. This is a large assumption, indeed.

An analysis of the oil workers at Tampico will indicate several problems with the above interpretations. First of all, to summarize what has already been demonstrated, there was little basis for an alliance between foreign capitalists and Mexican politicians. Their interests diverged more than they converged. The politicians were interested in containing social chaos and the oilmen hated tax hikes and losses of property rights. Did capital and the state disagree over taxes but still cooperate on labor matters? Did the revolutionary armies crush strikes, for example? Occasionally, yes. Most of the time, no. In Tampico, as this chapter will demonstrate, the attitude of the authorities toward workers had more to do with the state's traditional role as mediator of patron-client relationships than with preserving the capitalists' control of the labor market. Indeed, the Constitution of 1917, which reestablished the legitimacy of state mediation, worked against the companies' labor policies.

Those who worked for the oil companies were not hapless. The American workers conspired to resist the inclusion of the Mexicans into the better-paying jobs, it is true. Yet, this did not benefit the companies, which were forced to pay the foreigners higher wages. Anyway, foreign workers were not able to forestall the Mexican takeover of their jobs. Revolutionary turmoil, dangers in the countryside, and the war-time military drafts back in the States hastened the departure of American oil workers from the oil fields in Mexico. Besides, Mexican laborers had had a long tradition of resistance to proletarianization. Indian peasants and mestizo wage earners had preserved their independence and dignity by developing alternating stratagems. They moved from job to job, acquiesced to paternalism, resisted perversely, and even rebelled.[3] Both urbanization and the Revolution enabled the workers to practice old behaviors in new settings. They used traditional forms of social hierarchy to organize and to petition the state. Skilled workers formed

trade unions. They assumed leadership of the unskilled in order to reinforce seniority and rank in the workplace. (On the other hand, the companies wanted to promote employees on the basis of efficient work habits, rather than seniority.) When economic conditions threatened to reduce their standard of living, Mexican workers waited for propitious moments of full employment to strike for greater security. Even though the anarchist philosophy of their leaders may have cautioned against political alliances, the workers were politically adept. They knew how to petition — even coerce — the state into taking up their cause.

Finally, were the workers of Tampico revolutionary? Even though they may not have believed entirely in socialism, they did subscribe to ancient traditions of cooperation and order among themselves. Even though few actually fought in revolutionary armies, they did take advantage of the promised social reforms. They supported those politicians who listened to their demands. Even though they may not have actively supported a massive redistribution of property, Tampico workers did demand a more equitable distribution of income. In many ways, they became more nationalistic than socialistic. Their contribution to the ideology of the Revolution had always been "Mexico for the Mexicans," not so much to take property from wealthy Mexicans and foreign owners but to take jobs from American workers. Strikes occasionally had anti-American, though seldom anti-imperialist, overtones. Nevertheless, Mexican workers seized the opportunity of revolutionary turmoil to organize, to strike, and to resist the full implications of proletarianization. Scholars may look askance on their reformism and materialism, but Mexican workers did prevent the companies from converting them into working nonentities, mere sellers of labor power, and wage slaves.[4] Perhaps this was not the revolution that some observers wish they had had, but it was a world that the tampiqueños worked tirelessly — and remarkably successfully — to shape. These Mexicans constructed that world, insofar as modernity made it possible, according to their ancient customs.

Refreshing Breezes and Vilest Threats

The Great Mexican Oil Boom accelerated many of those social trends that the exploration and first discoveries had set in motion during the last decade of the Porfiriato. Tampico boomed as the new center of the oil-refining business. Foreigners arrived in large numbers

to lay claim to the skilled positions in an industry whose operations were conducted in the English language. Cultural and racial differences exacerbated the relationship between skilled foreigners and less-skilled Mexicans. Among the Mexicans themselves, differences existed. First-generation industrial workers, most of whom were itinerant peasants from the villages of the central plateau, did most of the unskilled lifting and hauling. They were not entirely proletarianized, because most retained some rights to subsistence in their villages. Still, the ravages of revolution, reducing peasant subsistence and mobilizing the rural population, rendered the high wages and work opportunities in the oil zone an attractive alternative. The population of this port and refining town burgeoned in an unprecedented fashion. Before the discovery of the Potrero del Llano well, Tampico was a port and rail terminal of some twenty-five thousand persons. The growth of refining and exporting swelled the population to more than seventy thousand persons by 1918.[5] The size of the city had nearly tripled in less than a decade. The largest contingent of foreigner newcomers were not, in fact, Americans but their Chinese auxiliaries. They had accompanied the new American conquistadores, like the sixteenth-century naboríos (Indian servants) who attended the Spaniards, as houseboys, cooks, and personal servants. Others became independent traders, shopkeepers, and laundry operators. The breakdown of foreigners in 1915 was as follows:[6]

|

These foreigners owned the choice residential properties, too. Tampico hill was transformed into "neighborhoods of elegant residences where the foreign population lived, enjoying a climate refreshed by the breezes from land and sea."[7]

Migrant workers crowded into makeshift housing along the lowlands and the banks of the lagoons skirting the city of Tampico. In Arbol Grande, site of the Pierce refinery, and Doña Cecilia, site of El Aguila's refinery, workers erected shanties (casuchas ) elevated on posts over the mud holes. Across the river, alongside the Huasteca refinery at

Mata Redonda, a sizable town of workers developed. It had its own church, market, plaza with gardens and musical kiosk, and sports fields. Closer to the refinery, the supervisory employees, most of whom were foreign, lived in "excellent homes made of wood, forming well-aligned streets and each house having a small garden."[8] The native itinerants suffered the most unhealthful conditions. In one rooming house, 57 persons lived in sixteen rooms. In another, 2,100 persons lived in thirty rooms. Those who decided to stay, allowing themselves to become proletarianized, undertook land invasions. Under their own leaders, they seized public and unused lands, divided up the lots among themselves, set aside land for schools, built homes with fences, and petitioned the government for private ownership. Rent was high, space scarce. Migrants raised chickens in the city to supplement their diets. The mortality rate also rose with the population. In 1910, it was 41 deaths per 1,000 persons, and in 1917, it was 66 per 1,000.[9] Little except the high wages and the expectation someday to move on made up for the unhealthful conditions of living in Tampico's slums.

Not only was the population growing by leaps and bounds throughout the course of the second decade of the twentieth century, but the commercial composition of the city was also being transformed. Petroleum and American trade gained ascendancy over general and multinational commerce. In 1911, mineral and agricultural exports dominated the ships' cargoes. But revolutionary disruption of mining and especially railway connections to the interior forced a decline in mineral shipments by 50 percent. "The roadways leading north and west from Tampico are in disrepair, the rolling stock worn out and grossly inadequate to the small present day needs," reported the American consul at Tampico, "and the service pitifully bad, unreliable and expensive."[10] Plans to construct rail lines from Tampico north to Matamoros and southwest to Mexico City were abandoned. Banditry and troop depredations, in the meantime, disrupted local agriculture. Also, American oil tankers came into prominence in Tampico's shipping. The ore carriers and general cargo vessels from England, Germany, and Norway arrived less frequently than before.

Meanwhile, the petroleum workers as a group rose to dominate the working class at Tampico. Of course, the oil proletarians did become quite militant. It was not because of their new positions in the export structure but because of the strong heritage of resistance, deriving from the colonial period and from previous worker action at Tampico.[11] The skilled workers, as much as anyone, delivered Mexican

working-class traditions to Tampico. Mechanics, carpenters, and boiler workers gained their skills in the railway shops and on the trains. These skilled and semiskilled Mexicans brought with them a certain cosmopolitan outlook. They considered themselves the natural leaders of the unskilled Mexicans. The work processes of modern industry, which gave the skilled workers positions of importance in production — running the engines or commanding the valves — reinforced this preindustrial differentiation but did not originate it.

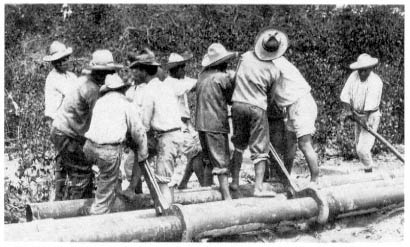

At first, the greatest demand for Mexican laborers existed in the construction trades. Clearing the brush, hauling materials and equipment, swinging machetes and shovels, and driving draft animals used many nonindustrial skills of laborers. As on the hacienda, construction peons worked day-to-day, laying off when the job was completed or when it rained.[12] They built roads, pipelines, pump stations, wharves, terminals, refineries, offices, and houses. Many oil companies secured their unskilled workers through the traditional Mexican contractor, the enganchador, much as the hacendados might. Eventually, foreign and national capital established contracting companies in Tampico that specialized in construction work for many oil companies. They were the Petroleum Iron Works Company of Pennsylvania, Jones and Gillegan, and House and Armstrong.

Initially, construction workers existed in Tampico in short supply. In 1913, when Huasteca, El Aguila, and Jersey Standard were constructing refineries at Mata Redonda and Villa Cecilia, wages for unskilled workers soared to 2 and 2.25 pesos per day.[13] As in harvesting wheat or shearing sheep, the peons worked in groups of ten to fifteen under the guidance of a capataz (foreman). Also like agricultural work, this kind of toil in Tampico was seasonal, interrupted by the rainy period. El Aguila's department of construction had a payroll that varied between 45 and 1,226 workers, with larger numbers during the dry season. Its regular work force in 1917 was 698 persons, and they worked under the tarea (piecework) system as did the first mining workers of the 1880s.[14] Since most of these construction workers were itinerant peasants, there was no loss of skill here. Artisans and skilled workers did not have to take up the unskilled positions. The demand for skilled workers elsewhere in the industry was great enough to prevent veterans of railway and mine work, the real proletarians of Mexico, from having to do the unskilled work. The construction industry hired carpenters and mechanics, as did the marine transport companies and port works. Brickmakers and masons found work in the construction of pump

houses and refineries. The wages of the mechanic rose from 2.50 pesos in 1907 to 7 pesos per day in 1914, because the demand was strong.[15]

These skilled workers were the first to organize trade unions. By 1910, the intrepid Mexican railway workers and office workers had established a Tampico branch of the Gran Liga Mexicana de Empleados de los Ferrocarriles. Skilled laborers organized into small groupings among the stevedores in 1911, marine workers in 1913, the laminated iron workers and bank and commercial employees in 1914. As they organized in 1911 and 1912 into a 720-member union, the Gremio Unido de Alijadores harbored great bitterness toward foreigners. Their communiqués "contained vilest threats expressed in the vilest language and stated that if the Americans did not leave this port within twelve hours they would be attacked on March 16 at 4 P.M."[16] The first unions were organized around the trades, cutting across the industries. There were sindicatos of carpenters (with 460 members), bricklayers (370), pilots (paileros ) (320), journeymen (jornaleros ) (533), and various occupations like clerk (542). Together, these early groups scored some nationalistic victories for themselves. When Casa Rowley, the monopoly freight contractor at the port, brought in West Indian workers to break the Mexican longshoremen's strike in 1911, the latter used nationalism to garner support from fellow power-and-light workers employed by another North American company. Together they won a victory over foreign workers.[17] West Indians, if not Chinese workers, disappeared from the Tampico environment.

In time, these first trade unions federated within their industries to form industrial unions. This was not the idea of the workers in the export industries themselves. It was suggested to them by representatives of the Mexico City labor confederation known as the Casa del Obrero Mundial. These capitalino labor organizers had arrived in Tampico in 1915 as elements of the famous Red Battalions, the armed labor contingents that had joined the Constitutionalist cause in 1914, shortly before the peasant armies of Zapata and Villa occupied the capital. As the political influence of the Constitutionalists spread, so did that of the Casa. Urban workers evidently felt little kinship with the peasant revolutionaries. However, their leaders did appreciate their own mission, like that of the Constitutionalist government, to spread their hegemonic influence over the peripheral industrial areas.[18] In the process of Mexican labor organization, the urban skilled workers of Mexico City, the traditional seat of Mexican artisanship and labor hierarchy, spread their influence over the outlying industrial areas.

Workers of Excitable Temperaments

What were the attitude and policies of the foreign employers toward the workers? They were not, after all, like traditional landowning patrones. For the most part, company managers treated their workers as any other factor of production: they attempted to control expenses and increase and decrease employment according to demand. Two factors prevented the companies from totally mercenary actions in this regard. They had to take care of their best workers and pay relatively high wages; the growth of the industry made good steady workers a scarce commodity. American managers appreciated the abilities and loyalty of some of the longest-employed Mexican workers. The former manager of the Huasteca topping plant at Tampico admired those who had worked for the company for twenty years. "They [still] need the steadying hand of the American to direct them," he said, "but otherwise there was little to be said against them before the revolution."[19]

But others did not trust the Mexicans. At the El Aguila refinery in Tampico, which employed approximately six hundred men in 1918, the managers regarded the Mexican workmen as dishonest. Only Englishmen and Americans were in charge. "On the whole the management felt no particular obligation toward the workmen," reported an American observer. "[The managers'] main purpose was to make the company pay."[20] The first companies in Mexico had used local authorities to instill labor discipline at their installations. During the Porfiriato, it was common for the companies to acquire the services of the rural police or company policemen appointed by the local jefe politico. The objective was to prevent the men from drinking on the job; the managers claimed that Mexicans who drank on the job became unruly, surly, and unproductive.[21] Once the Revolution began, however, the use of company police, aside from the watchmen, was not possible. The new governments disapproved.

Oil companies paid high wages during the full employment era of the Great Mexican Oil Boom. But once committed to wages at certain levels, employers were reluctant to increase the pay at the demand of their workers. During the First World War, as we shall see, the workers suffered from the rising cost of living. Were the companies willing to raise wages to offset these price raises? Not at all. Lord Cowdray was probably typical of the other owners. He did not want to raise wages,

despite labor's increased suffering, because giving in to demands for higher wages, he said, would only encourage further demands. Cowdray did not believe that he could increase wages, "for the simple reason that wages once increased cannot, in all probability, be lowered."[22] Instead, he preferred to provide a kind of social assistance, in the form of a company store that provided food and clothing below cost. Huasteca was doing the same.[23] In this way, wages would not have to be readjusted later, costing the companies some of their absolute control of the terms of employment.

It was largely to secure workers and not necessarily to pay them more that the companies also undertook additional paternalistic practices. At the Minatitlán refinery of El Aguila, more isolated than the Tampico works and not serviced by a rail line to Mexico City, pay and material standards may have fallen below the level of Tampico. Nonetheless, the demand for labor was quite high. An El Aguila manager, in May 1920, was still bringing as many as 150 workers at a time down from Mexico City. He paid for their transport from the capital by rail to Veracruz, thence by launch to the isthmus. If the climate at Minatitlán was not agreeable to them, he promised to pay their return fare.[24] Foreign oil companies also provided motion pictures; instituted employee savings plans; and furnished housing, medical facilities, and primary schooling for the children of some Mexican workers. The Huasteca terminal and refinery at Mata Redonda provided two- and three-room cottages to native workers but mostly to the "better class of mechanics" rather than "the common peons." The former were more difficult to secure than the latter.[25] The skilled Mexicans lived better than the peons. Both were separated from each other as well as from the much more privileged foreign workers, whose housing, provided by the companies, was far superior. In 1918, during a time of much labor unrest, Huasteca finally built a schoolhouse for the children of its Mexican workers. It hired and paid for three teachers. "So far the work in this school extends only to the first two years of the ordinary course with a few classes belonging to the third grade," observed an American visitor. "Ultimately [the head teacher] plans to have the four grades of the elementary primary with some work in gardening and manual training."[26]

Most large companies also hired nurses and even doctors, Americans and Mexicans. El Aguila's refinery had an extensive medical facility, yet provided separate care for foreign employees, another facility for Mexican skilled workers (mecánicos, carpinteros, and rayadores de tiempo ), and

a third for unskilled workers. The 328 patients (out of 900 total employees at the refinery) passing through the clinic during July 1919 were treated for these maladies:[27]

|

It is difficult to escape the impression that the companies developed these social amenities not only to increase productivity but also in response to worker unrest.

Yet, the paternalism of the oil employer had its limits. A discharged worker was required to leave company housing and forego company benefits; there was no severance pay. Few men worked on other than short-term, verbal contracts; no collective contract existed at all. Fortunately, high demand for workers meant that jobs were plentiful elsewhere in Tampico and the oil zones. But accidents exposed the worker to insecurity in a labor market controlled by the employers. Jose I. Hernández mutilated his leg installing boilers for Huasteca at Mata Redonda. He received medical treatment and his salary while recuperating in Tampico. But when his leg did not heal properly, Hernández had to seek his own medical treatment in Mexico City. The company did not provide him any financial help there whatsoever.[28] Workers soon realized their vulnerability in the new industrial environment.

A second aspect of the companies' attitude toward its workers — fear of labor radicalism — also stemmed from the employers' jealous defense of their autonomy in the labor market. Oilmen ultimately desired not to give up any control over labor costs, the better to meet volatile international market conditions. Radicals threatened that control. They organized the workers, agitated for higher wages and benefits, and fomented strikes when employers refused. Most of the time, the oilmen considered that the Mexican labor militancy of the war years was attributable to the "very excitable temperament" of the Mexicans or to their susceptibility to be stirred up "by any orator who gets a hearing." As one oil manager said in 1918, "The strikes that have come of recent years have been mostly engineered by men who took advan-

tage of some particular grievance or some local situation in order to gain notoriety."[29] In other words, the employers did not believe the proletarians had any justification for their alienation. Those Mexicans who attempted to gain control over their own conditions of employment were simply victims of emotion.

Such being the case, the oilmen tended to denounce all labor agitation as a plot of the dark, sinister forces of the Industrial Workers of the World, the infamous I.W.W. Or else it was German sabotage. When Tampico workers began a round of strikes in 1917 to offset the rising cost of living, the oilmen cooperated in raising the specter of mindless anarchism. It was nearly pathological. The oilmen's publicists in the American press wrote of I.W.W. agents circulating among the workers at Tampico. The Union of Port Mechanics, which led a port strike in 1917, was called "the I.W.W. in sheep's clothing."[30] When the United States entered the war, these same men advanced the idea that German money financed the strikes. Following the war, the center of international labor agitation shifted from Germany to Soviet Russia. Labor agitators at Tampico in 1919 were now the "Bolsheviks." Foreign employers had only to point out that some Mexican labor leaders published a newspaper called El Bolsheviki or had formed a group called the Hermanos Rojos as proof I.W.W. agents now worked for Moscow. Senator Albert B. Fall was collecting a thick dossier on labor agitation in Tampico. Some of his confidential correspondents made the most unfounded connections between labor radicalism and Mexican politics: Plutarco Elías Calles was a "Sonora Radical"; Adolfo de la Huerta was a "rabid socialist."[31] A right-winger named William M. Hanson exposed the links between the I.W.W. and the Mexican labor confederation, the Casa del Obrero Mundial. Writing for William Buckley's American International Protective Association, Hanson connected the I.W.W. and the Casa to President Carranza and his favorite generals.[32] The attitude of the foreigner toward labor unrest at Tampico was neither enlightened nor fraught with understanding.

Men of Judgment and Determination

The reader may ask: What was there to understand? Did not the foreign employers provide Mexicans with high-paying jobs? Was it not true that the oil proletarians willingly entered employment,

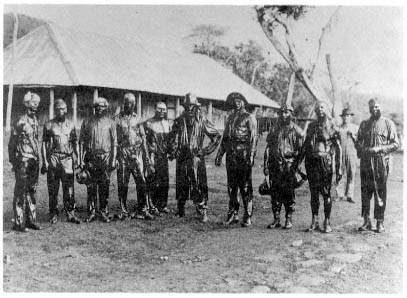

Fig. 14.

Americans who capped an El Ebano well, 1904. Ten oil-coated workers

pose in front of their dormitory after placing a valve over a gusher at El Ebano.

the Mexicans who assisted are not shown and lived in a different billet.

from the Estelle Doheny Collection, courtesy of the Archive of the Archdiocese

of Los Angeles, Mission Hills, California.

thereby gaining social status and avoiding the economic consequences of the Mexican Revolution? Were not the oilmen correct in thinking that they provided valuable employment opportunities Mexicans might not otherwise have had without the foreign investment? To all these queries, the answer is "Yes, but. . . ." Along with the undeniable benefits of industrial employment, especially higher standards of living, the oil companies also introduced the labor by-products of modern capitalism: the insecurity and dependency of proletarianization. Moreover, because of the prominent role of foreign capital and technology, the oil industry reintroduced the old problem of cultural subordination. U.S.-led capitalist change implied that the Mexican workers exchange their cultural heritage for modern social relationships. The tutors of this cultural revolution were skilled American workers. Therein lay the rub.

In the United States, the oil field hands were a notoriously hardliving, mobile, and independent lot, known for moving across the con-

tinent like migratory swallows. They had followed the oil booms from Pennsylvania down through the Mississippi Valley to Texas and Oklahoma. The Great Mexican Oil Boom was like any other. Their peers described the American oil workers as both good men and bad, many of the latter escaping the law in the United States.[33] Their employers in Mexico constantly had to compensate for their often less-than-desirable work habits. They drank, caroused, chased women, and sometimes held up refinery operations while supervisors bailed them out of jail after weekend debaucheries. Other foreign workers spent inordinate amounts of time at sick call. El Aguila had foreign pump station engineers who were always absent from duty for some illness or other. Already, foreigners were receiving the preferential treatment of a week to ten days' worth of paid holiday every three months. If dismissed, the Americans also got one month's severance pay. At any one time, as many as 2,500 Americans and 4,000 other foreigners were working in the oil zone.[34]

Foreign workers retained their penchant to be on the move. A great majority did not stick with any one job for so much as one year. The U.S. consul's record of American workers leaving Mexico because of the revolutionary turmoil of 1913 and 1914 offers a rare statistical glimpse into this mobility. Among the foreign workers choosing to leave the oil zone at this time were rig builders, drillers, tool pushers, electricians, station men, male stenographers, construction engineers, timekeepers, machinists, steam fitters, oil gaugers, pump men, barge men, still men, refining superintendents, auditors, well contractors, pipe men, transmission bosses, stable men, firemen, train engineers, brakemen, and gardeners. Willis Lee, who had his family with him, and A. J. Kelley were long-time well drillers who had been in Mexico since 1903 and 1907, respectively. But most evacuees had been there for less than six months. A survey of the Americans leaving through Tampico in 1913 and the first four months of 1914 indicates the following statistics on the length of stay at their last job:[35]

|

Many of these men indicated they would not be returning and obtained one-way travel tickets out of Mexico. American workers abandoning mining, smelting, and railway jobs had been generally longer-term employees than those from the oil industry. Few American workers, many of whom had supervisory positions over the Mexicans, had been in the country long enough to learn the culture and language — indeed, if any of them had wanted to.

Differential privileges, hardly a new feature in Mexican life, greatly complicated the relationship between the foreigners and the native-born workers. The Americans received higher pay. As everywhere, drillers got the best pay of all, $250 to $350 per month, paid in drafts drawn on the Chase National Bank in New York or other U.S. banks. In addition, there were allowances for food and housing. Most of the time the foreigners ate at company cafeterias — for free. "When I come back to the United States after working for those Britishers," said a former employee of El Aguila, "my teeth was just about worn down to the gums, I'd eaten so much and so good!"[36] Although Mexican peons hired on for one peso or more per day, the American drillers on twelve-hour shifts were getting up to six dollars, including room and board. Competition for American workers, made scarce by revolutionary depredations, tended to reinforce their wage privileges. "With the several other oil companies operating in the district," observed an El Aguila oil field manager, "the wage invariably paid to foreigners, whether they are Mechanics, Engineers, or Pipe Liners, is $10.00 Mex. gold per day, and outside of Tampico in the Fields they are furnished with free quarters and living. This wage is invariably paid to all [foreigners], many of whom are of a very indifferent class and who drift from place to place filling one job after another." The best Mexican laborer never received more than eight Mexican gold pesos per day.

Housing for the Americans and Britons was separate from that of the natives. In the El Aguila camps, the foreigners' housing had been shipped out from England. Single male foreigners lived in bunkhouses with kitchens in the rear. Chinese workers did the cooking and laundry and waited on tables. At Minatitlán, the Chinese also had their own separate dwellings.[37] "Not only does this difference between the foreigner and the Mexican exist at the refinery," reported a Mexican official, "but also they established another, which is more important for the welfare of the worker, and it is that they pay the foreigner in goldbacked money and the worker in paper money, although they have had to raise the latter by a few percentage points because of the high cost of

living."[38] The presence of foreign workers not only created a privileged caste within the oil industry but restricted the upward mobility of the native-born workers. A government petroleum inspector described the consequences of the foreigner's presence at the Minatitlán refinery. He referred to the slow pace of technological transfer:

The administrative personnel of the refinery is foreign; he who deals directly with economic and administrative matters is English; the technical personnel in charge of the refinery are Austrian, with the exception of the civil engineers, who are Englishmen. All the workers are Mexicans, and it is very rare to see them occupying positions of importance in the refinery, except a few in the offices working as stenographers or doing accounting. The foreigners always show much reserve in their knowledge, whether from personal egotism or at the instructions of the company, but the result is that they never have given the Mexican an opportunity to improve nor do they show him more than absolutely necessary to discharge the task they assign to him, without permitting him to learn the connection that his work has to the other functions within the refinery.[39]

Short-term foreigners were not known for their diplomatic courtesies nor did they demonstrate a high regard for their hosts. American drillers, tool pushers, and "boiler farmers" at the derricks were surrounded by groups of three or four Mexican helpers. "Course they never could learn the technical nature of the business," said one American. The Mexicans had "no curiosity." Said another: "Most of [the Mexican peons] didn't know a drill bit from a tamale shuck."[40] El Aguila restricted the management jobs to Englishmen, especially those with the ability to speak Spanish. They found that the Americans showed little inclination to learn Mexican ways or to practice diplomacy.[41]

The war tended further to disrupt the balance within the group of foreign workers. Many employed in the industry had fled to Mexico so they would not have to serve in the U.S. armed forces. Following the war, a sizable number of American veterans found employment with the oil companies. Among them was L. Philo Maier, a graduate of the Colorado School of Mines, who had served in France as an officer in the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. E.J. Sadler had recruited him to work in the expanding operations of the Transcontinental Petroleum Company recently purchased by the Standard Oil Company of New Jersey.[42] Other Americans formed a Tampico chapter of the war veterans group, the American Legion. The Legionnaires were not well liked by the Mexicans. The growing number of federal officials in the oil zone especially resented these war veterans. López Portillo remembered

them as men imbued with ideas of their national and racial superiority. They failed to recognize his social status, for instance, calling the young oil department technocrat a "Mex," as if he were a common laborer. "I learned my lesson," this son of a former cabinet minister wrote.[43]

The companies attempted to staunch the hemorrhaging of their better foreign workers during war and revolution. Naturally, many left to escape the insecurities of the revolutionary turmoil and robbery, particularly in the oil fields. The popular reaction to the American invasion of Tampico had set many Americans to flight. Most did not return and they were not replaced, a situation that was also true for the mines, railways, and even the Tampico Tramway and Power Company. After World War I began, El Aguila could not prevent its British employees from volunteering for military service. But Lord Cowdray and J. B. Body also considered their work as a patriotic service to the homeland, inasmuch as El Aguila provided at least some of the British fuel requirements during the war. They consulted with British diplomats to exempt their employees from Britain's military draft. Beginning in the summer of 1917, many Americans were also leaving El Aguila for military service, and they could not be replaced.[44] Given their considerable hardships during the Revolution, the American workers became quite reactionary. They complained of insufficient support from their own companies and formed a vocal group advocating U.S. military intervention. Huasteca and The Texas Company had great difficulties getting their American workers to stay on the job amidst the comings and goings of constitucionalistas and pelaecistas.[45] At Minatitlán, the revolutionary raids made the American technical staff very nervous. They requested that American gunboats be stationed on the Coatzacoalcos River, but it had been insufficiently dredged. There and at Tampico, the Mexican workers had been taking advantage of the fluid political situation to vent antiforeign sentiments. Native workers resented the jobs held by the foreigners.[46] No doubt they also resented much else about the foreigner's presence.

Gradually, the companies had to train the Mexicans to replace those Americans and Britons who departed. It took time. "Regarding the use of Mexicans as Second Engineers," wrote one El Aguila supervisor in 1916,

our experiences in this locality do not seem to have been encouraging; we have at times had Mexican "Seconds" at both Tanhuijo and Tierra Amarilla [pump] stations, but when the plants were enlarged it was no longer considered safe. In past times it was easier, and we hope it will again become so, to get Mexicans of sufficient stamina for those positions. To carry on the opera-

tion of the plants according to the standards we have set, to keep up the records in an accurate and reliable manner, and to act promptly in case of occasional emergency require men of training, judgment and determination. Of course, under existing conditions, with the country full of bandits, the change would not be possible; at times all the Mexicans have left our stations and the work has been carried on exclusively by the foreign engineers employed.[47]

El Aguila was not confident about the process. Its managers thought the poor education of the Mexican workers did not make them fit substitutes for American drillers.[48] Although the training of Mexican workers permitted the companies eventually to reduce their labor bill, the circumstances of war and revolution motivated the shift more than did any company policy to promote Mexican workers.

Nevertheless, the shift was made, and the demand for large numbers of skilled and experienced American oil workers declined somewhat. By 1919, Huasteca's workshops had Mexicans doing all the wood-working, steel, and machine activities, and copper and brass fittings. Only one American, the supervisor, remained in each department.[49] Foreign women, no matter what their skills, had never received much encouragement from employers, and by 1919, the American consul at Tampico was also discouraging men from coming to Mexico for work. "The Tampico employment situation is becoming an acute one now to those coming here without previously making arrangements," the consul wrote in response to an inquiry. "Living is very high and you might find yourself considerably embarrassed if you come to Tampico looking for a connection."[50] The general manager of Jersey Standard's Transcontinental also discouraged American workers. "We are glad when possible, to give ex-soldiers and sailors employment," E. J. Sadler said, "but find it disadvantageous to bring men from the States, when it is not absolutely necessary on account of their special training or adaptability for our work."[51] The days when even moderately skilled Americans easily found jobs in the Mexican oil industry were gone forever.

Regretting the Caste System

Years later, when the Mexican state was about to take over the entire industry, Mexican economist Jesús Silva Herzog wrote about the two categories of Mexican oil laborers. The first category consisted of the settled refinery and terminal workers. They were

urbanized, skilled or semiskilled, more highly paid, and often had access to company housing. The oil-field workers, on the other hand, were a rather less skilled, more transitory, and poorly housed group.[52] These two groups experienced rather different conditions during the period of oil boom and revolution. Partly based on their place in the production process and partly on the revolutionary turmoil, the oil-field workers suffered insecurities and dangers. Their brethren at the refineries and terminals, however, grew more militant. It may appear a paradox that the most privileged of the Mexican oil proletarians also became the most demanding. But that only highlights the essential ingredient to success in labor organization: militancy begins among those who have the most to lose in the new industrial setting and who are in a position to disrupt production. The skilled refinery worker qualified for the task. The oil-field laborer did not. To a certain degree, this difference was a result of the new industrial setting — or of the production process, as the new labor historians call it.[53] On the other hand, the production process in oil refining that differentiated workers by skill, privilege, and wage also reinforced traditional forms of hierarchy familiar to Mexican workers. Therefore, militant workers too sought to combine old traditions with new opportunities to achieve independence and security in the modern industrial setting.

At the time, few observers doubted the privilege accorded to those Mexicans who worked at the refineries and terminals, at the nexus between the Mexican economy and the international markets. All the pipelines and barge traffic in crude petroleum terminated at the refineries. From these points, the petroleum products and the crude and partially refined oil passed via the on- and off-shore loading facilities to domestic and especially foreign markets. Tampico was the biggest and most important center of refining and shipping. Tampiqueño refinery and terminal workers, therefore, performed their duties at the very hub of oil's production process. The employers likewise recognized the central importance of these urban workplaces. They strove to make the refineries the focus of their paternalistic regard for these important workers. "In all the neighborhoods formed around the Tampico refineries, with homes for employees and workers," recalled the geologist Ordóñez, "one always observed cleanliness, hygiene, and order. They gave the clear impression of how one could live immune to the tropical climate with their continuous campaigns against mosquitos and with hospitals, schools, ice factories, drainage systems, etc., etc."[54]

The Huasteca refinery camp at Mata Redonda, on the southern bank of the Pánuco River across from Tampico, boasted a clean slaughterhouse, two motion pictures per week, an elementary school with five teachers, water- and sanitation works, and plumbed homes. At Doña Cecilia, the El Aguila refinery also had a schoolhouse and even a gymnastic society with a membership of fifty Mexicans. Here one found duplexes for the families of Mexican mechanics and nine peons' dormitories with sloping, corrugated tin roofs, all constructed on terrain high enough to escape the 1913 flood.[55] Many workers lived in Tampico and the surrounding suburbs of Doña Cecilia and Arbol Grande. They traveled to work on the trolley cars of the Ferro-carril Eléctrico that ran along the riverbank from Tampico to La Barra. El Aguila had the industry's largest refinery, employing between six hundred and one thousand men.[56] The housing at the older Pierce refinery at Arbol Grande had not been maintained in as good condition as the newer facilities of Huasteca, El Aguila, Transcontinental, and The Texas Company. In fact, the Pierce compound was dangerous. A fire broke out at the tank farm of the refinery in 1912, burning thirty-five houses in the vicinity and killing a little girl. The Tampico municipality was unprepared to battle the blaze. It was put out only after Herbert Wiley and five hundred men from Huasteca arrived to extinguish the conflagration.[57]

A visit by a labor department bureaucrat early in 1920 revealed the conditions of relative privilege enjoyed by Mexican workers but indicated also their clear subordination to foreign personnel. The company housing was divided into two sections. On the highest ground, an exclusive neighborhood of "homes made of masonry," there lived the foreigners and the few Mexicans of high authority, such as the assistant engineer to Superintendent Coxon. Although the housing for Mexican mechanics and peons was on the lower ground, Colonia Baja was still healthy and sanitary. "I can assure you that the conditions of hygiene and health of the terrain occupied by the habitations for workers and day laborers are good enough. The Manager of the Colonia, Mr. W. N. Collins, takes special care that they maintain the greatest neatness possible in all the habitations of that place."[58]

An American who spoke good Spanish operated the "Peon Restaurant." There the Mexican workers paid up to one peso for meals "of good quality and according to reports from those same workers, the price charged is in accord with the quality of food that is purchased." The American workers and foreign supervisors, however, ate

separately. The cooks for both cafeterias were Chinese. Single men who did not live in town paid fifty pesos per month to obtain room and board at the "Club," as the peons' hotel was called. Cerdán found that the food also was good and the rooms clean and hygienic. He said that the men paid only half of what it would have cost them to have similar accommodations outside the refinery compound. Assuming a beginning peon made sixty pesos per month, he was living close to the margin. The school, inaugurated in 1919 and staffed by three teachers, had only sixty-five boys and fifty-two girls enrolled in grades one through four only. Students wore uniforms, "with the objective that there be no distinctions between children of clerks and those of workers and day laborers." Considering the large number of workers, most Mexicans were not sending their children to the company school.

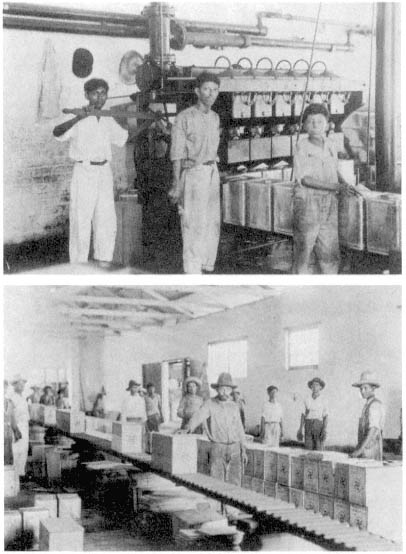

Did all this privilege translate into a quiet, pliable labor force at the refinery? Cerdán observed that of the 950 Mexican men working at the El Aguila refinery, 820 of them belonged to the Obreros Unidos de la Refinería "El Aguila." The high technological level of plant production placed the refinery workers under constant pressure. Every day, the refinery used more than ten thousand kilowatts of electricity from the (American owned and operated) Compañía de Luz, Fuerza y Tracción de Tampico. Electrical pumps drove the crude oil through the elaboration process and moved the product through the bulk loading facilities into the holds of 750-ton steam tankers. The management constantly renovated the machinery in the can and box plant, to increase both productivity and safety, Cerdán noted. The paraffin plant employed the "Carbondale" system, apparently the cutting edge of refinery technology. Workers at the sulfuric plant lived under the incessant danger of accident, explosion, and fire. "During the entire process of the manufacturing of [sulfuric acid]," Cerdán indicated, "the vigilance that is exercised over the operators is very considerable, with the goal of avoiding an accident that imprudence might originate and that would have fatal consequences for all of them." Although the work could be demanding, one did not find much in the way of coercion. The companies later came under attack for having guardias blancas, company police who controlled the labor force. El Aguila's refinery did have special guards, as the labor inspector noted, but "they are limited only to seeing that none of the materials employed there are taken from the place without the express order of some Chief." Mexican workers had not forsworn their tradition of helping themselves to the property of their

employer.[59] The work could be demanding, but there appeared to have been no erosion of skill levels among the Mexican employees. If anything, the rapid expansion of the refinery business at Tampico rapidly outstripped the supply of local artisans and trained mechanics.[60] Why else would the companies need to hire expensive, obstreperous foreign workers, when Mexicans would have been cheaper?

Although they afforded the workers a higher standard of living, the refineries nonetheless promoted — or acquiesced to — a hierarchical social structure among their workers. The Texas Company terminal on the south bank of the Pánuco River at Tampico maintained five classes of company housing. At the lower end of the social (and skill) scale, construction workers and part-timers occupied "ordinary thatched huts." No one regulated the sanitary conditions of this community at all. Full-time unskilled peons and their families inhabited two-room wooden cottages with no kitchen. The homes of the families of Mexican mechanics contained three rooms, including a kitchen, and had separate laundry and toilet facilities. Unmarried Americans lived in a clubhouse providing room, board, and recreation, including reading and game areas, billiard tables, tennis courts, and complete bathing facilities. Families of American employees inhabited five-room cottages, "well kept, well cared for and presenting a very attractive appearance," according to one American visitor.[61] The observer had no difficulty at all in understanding why The Texas Company maintained company housing, particularly for the Mexican workers. He said the company acquiesced to laborers' expectations of higher standards of living, "and they can be kept from the worst excesses of the I.W.W." Nonetheless, in the process, a strict hierarchy was established. "The American managers uniformly regret this caste system," the visitor noted, "but find that they have to comply with it."[62] Apparently the skilled Mexicans wished to live separately from the peons, and the Americans, from the Mexicans — a behavior among the working classes having much precedence in Mexico.

In addition, the wage system also reinforced the hierarchy of work traditional to the country. The Americans and Britons were paid in stable foreign currencies, either the U.S. dollar or in Mexican currency according to the exchange rate of what was called the Mexican gold peso. Each Mexican gold peso was worth fifty cents (U.S.). Some Mexican mechanics, the generic term given to skilled and semiskilled native workers, also earned their pay in gold pesos. Most peons and

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

part-timers earned wages paid in Mexican script. The problems of Mexican paper money had to do with the great inflation of the revolutionary period. By 1916, for example, the Mexican paper peso was worth 12.50 gold centavos, or a bit more than 6 cents, which occasioned El Aguila's accountants to maintain double and triple entries in their pay books. The foreign personnel earned up to two to four times as much as the highest paid Mexican. At El Aguila's Tampico refinery, the foreign superintendent earned 700 gold pesos per month and the foreign chief of stills got 355 pesos. While foreign administrators earned from 250 to 520 pesos a month, the Mexican supervisors earned from 60 to 200 pesos. At the stills, the foreign chiefs earned 355 pesos and the foreign still men earned between 180 and 300 pesos per month. But the highest paid Mexicans, three sample men, received just 150 pesos. In the pump houses, on the pipelines, and at the terminals, the foreign supervisors got 240 gold pesos per month, while the Mexican workers earned 135 pesos.[63] Among the Mexican workmen themselves, there remained distinct wage differentials. Mexican mechanics started at 5 pesos per day in 1920, and their assistants got only 1 peso (see table 10).

Income differentials such as these separate the modern class society from the caste society. Where once the differences in race and ethnicity had determined one's position in the working class, now the industrial wage accomplished the same task. Yet, there remained some similarities between the caste and class societies in industrial Mexico. Foreign personnel occupied the ranks of privilege, exactly as had the Spaniards in the colonial period. Native-born mestizos occupied the ranks of the semiskilled. Itinerant campesinos, many of them Indian, entered the work force at the lowest rank as peons. The educated Mexican disdained the whole lot and disapproved of their high pay in the oil industry. "The extravagance of workers and their families came to be exaggerated," noted the urbane engineer, Ordóñez. "[W]ives of simple peons and foremen dressed ostentatiously in silk stockings, expensive footwear, and silk dresses poorly made and inappropriate to their class and conditions."[64] Actually, this new social hierarchy had many similarities to past Mexican models — except that the non-Spanish speaking, non-Catholic foreign workers were not immigrants and could not be absorbed. The transitory status of foreigners rendered their positions susceptible to erosion.

The increased standards of living notwithstanding, the new industrial environment of Tampico produced a certain degree of alienation among the Mexican workers. It was not so much the rationalization of the work process or the hierarchy, which to a certain extent protected the social status of Mexican skilled workers. Part of the alienation had to do with the privilege of foreigners, which at times amounted to a cultural affront to Mexican laborers.[65] On the one hand, the privileged position of foreign workers blocked the upward mobility of skilled Mexicans. On the other hand, the company's absolute control over hiring, training, and promotion also pressured skilled Mexican laborers from below. They could never be sure that they might not be replaced by lower-paid, less-skilled peons. In spite of their status and material well-being, therefore, the skilled natives were the most insecure and unhappiest of all. As long as the employer controlled the workplace, skilled Mexicans never knew when they might be replaced by workers trained by the company. But they were also in a position to do something about their insecurity. The skilled Mexicans could organize; they could strike; they could exert some control over the unskilled; and they could seek the government's assistance. In the oil refineries at Tampico, they would eventually do all of these. Not their brothers in the oil fields, however.

Withdrawing Without Provocation

In general, workers in the oil camps, among the wells and pump stations, were less skilled and less privileged than refinery laborers. More primitive conditions governed their lives in the countryside. Nevertheless, the oil-field workers still enjoyed some of the same opportunities (though restricted by revolutionary depredations) in addition to similar limitations of advancement. Small towns had sprung up throughout the oil zone during the boom. Along the railway lines through Chijol and El Ebano and between the great oil camps of the Faja de Oro, migrants established little population centers quite miserable in their amenities. Geologist Ezequiel Ordóñez, like others of his class, had a somewhat puritanical attitude about workers. He described these small populations as "seedbeds of disorder, abuse, and vice." Ordóñez thought that the prohibition of alcoholic beverages at the numerous cantinas would do wonders to make life respectable. Petty despots there controlled even the necessities of life. Ordóñez described how enterprising persons, without authorization, would tap into the water lines of the companies and sell the water for exorbitant prices to rural inhabitants.[66]

For those workers living inside the compounds of the oil camps, modern technology provided amenities, even if it could not protect them from the shocks of revolution. El Aguila personnel lived in wooden bunkhouses with bathhouses nearby. "These buildings are constructed of rough pine lumber, without any inside boarding, and framed upon hard wooden posts for foundations," as one company official described them:

All exposed woodwork [receives] two coats of good oil paint. Corrugated iron roofs are used with canvassed ceilings. All window and door openings are properly screened throughout with bronzed gauge screening for protection against mosquitos; for the living quarters, verandahs are built on the most suitable sides of the house.[67]

The camps also provided company stores, which often sold supplies and basic foodstuffs like corn and beans at discount prices. Single men ate at the company restaurant. By the end of the oil boom, the biggest camps had modest schoolhouses for the children of Mexican workers and sanitation and water works. Huasteca's property at El

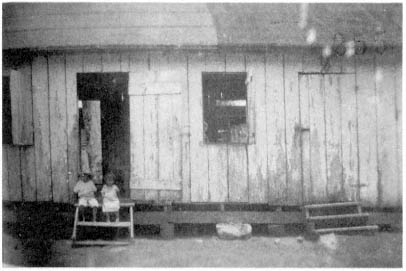

Fig. 15.

Mexican workers' housing, 1920. in the oil field of the Cortez Oil Company,

workers and their families lived in one- and two-room units in the same long

one-story building in which other families resided. Doors and windows on

either side admitted the breezes as well as the insects. from the Ramo

del Trabajo, Archivo General de la Nación, Mexico City.

Ebano was a veritable community. At any one time, up to five thousand workmen might have had ten thousand additional family members living with them in the oil camp. At Christmas time, the company entertained its employees with a sumptuous barbecue, in which the Americans served the Mexicans — surely a symbolic gesture only. In 1913, there were games, horse races, and an inspirational speech by Judge Jacobo Váldez.[68]

The small companies and the less productive oil fields, however, could not sustain the amenities of the larger camps like El Aguila's at Potrero del Llano, or Huasteca's at Cerro Azul. In the transitory camps, housing was very rudimentary, and sanitary conditions were often lacking. Still, government labor inspectors often found "very good conditions of security and hygiene" in the smaller camps of the Atlantic and the Cortez companies. Foreigners and Mexicans ate the same food, albeit at different tables. Other camps, at Saladero and Puerto Lobos, separated the housing and mess halls for foreign and Mexican

workers, tending to "deepen more the differences," as a government representative reported. At the Atlantic camp, the inspector said, "the treatment of the employees ... is always just and on some occasions even venerable."[69] The workers did complain, however, that the Chinese restaurant concessionaire refused to extend breakfast hours from 8:30 to 9 A.M.

Like the refineries, the oil camps gave in to the demands, particularly of its skilled workers, to provide separate housing and maintain the wage hierarchy. The Americans did not want to live or eat with the Mexicans; the Mexican skilled workers did not wish to live the same as the more transitory peons, and no one cared to mingle with the Chinese cooks and servants. Large camps separated the housing and operated segregated mess halls. Wage disparities also remained, especially between the foreign and the native personnel. On the drilling crews, the American drillers and tool dressers made between ten and fourteen gold pesos per day, while the Mexican firemen and helpers earned two and three pesos. The American rig builder worked for fourteen pesos per day and his three Mexican helpers got two to four pesos.[70] The Mexicans themselves earned higher wages than they could have in other lines of work. They even got 30 percent of their wages while on sick call. As the oilmen were fond of pointing out, other Mexican employers such as landowners and businessmen disliked the foreign employer "for spoiling their cheap labor."[71] There also remained a hierarchy of pay among Mexicans. The foremen (cabos ) of construction crews received up to 3.00 gold pesos per day; the peons received 1.50 pesos. Carpenters earned 4.00 pesos, blacksmiths and teamsters, 3.50 pesos; watchmen 3.00 pesos, and a camp peon 2.00 pesos.[72] There were almost as many peons in the various oil-field crews as skilled workers — but many more in construction. The wage hierarchy among Mexicans differed little from the colonial mining industry or from traditional hacienda work.

Meanwhile, the companies paid the Chinese workers the lowest wages of all. At the Potrero camp of El Aguila, twenty-five Chinese men were employed in the boarding of the foreign and Mexican employees of the construction and pipeline departments. But their monthly wages averaged less than Mexican workers. The Mexican "stable peon" made as much as the Chinese "kitchen chief" (see table 11). To a certain extent, the workers themselves determined what wages they would work for; no American would accept a Mexican's pay and no Mexican a Chinese wage. Therefore, the capitalist had to ac-

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

cept the traditional ethnic divisions of labor produced by the multiracial environment. No doubt cost-cutting employers would have preferred paying everyone the Chinese wage. But they could not.

Oil-field workers, however, endured two opposing stimuli during the period of simultaneous revolution and oil boom. On one hand, foreigners, Mexicans, and the Chinese alike all benefited from full employment. On the other, they all suffered from the insecurity caused by military and bandit activity in the countryside. The Mexicans, in particular, already encountered the customary change in time and work discipline when they entered oil-field employment. But the oil camp peons resisted giving their lives over completely to proletarianization, that is, working exclusively for industrial wages. As a labor inspector said, "The majority are from this region who work only in times in which there are no harvests. When harvests come, they leave their work, because some of them are owners of small plots which they sow for their own benefit."[73] The more skilled refinery workers did not have the same alternatives to proletarianization.

Nonetheless, the oil camps offered the Mexicans no security at all from the depredations of the Constitutionalist troops. To rob them, carrancistas shot the Mexican peons who were building a tank farm at The Texas Company field on the Obando lease. Eighteen carpenters working on a Huasteca pump station fled for their lives after the Constitutionalists took all their clothes. (The company, by the way, refused to reimburse them. Their loss was termed "a burden of Mexican

citizenship.")[74] The managers of company after company complained of the impossibility of keeping men on the job because of the "unsatisfactory and disturbed condition of affairs." Fortunately for the companies, most of the pipelines had already been built when the first outrages began during the Madero revolt. Thereafter, work on tank storage and other facilities had to be delayed from time to time.[75] Both Mexicans and Americans were abandoning the insecurity of the oil camps. "In normal times," reported the manager of the Furbero camp, "the company employes [sic ] about 600 men in the oil business and on its pipelines, railways, etc. Since 1914, however, this number has been reduced to 200, most of whom are Mexicans. All Americans have been withdrawn from the field and their places have been taken by Englishmen."[76]

Given the conditions in the countryside, the employers praised their oil-field workers, more so than refinery workers, for their loyalty. Managers often pointed out those instances where Mexican peons showed great fealty in the face of revolutionary despoliation. During the tense final weeks of the Madero revolution, Herbert Wylie said, the Mexicans patrolled the oil camps at night while American residents slept with their doors unlocked. He recalled asking them if they would be prepared to fight. "Si, señor," came the reply. "We will fight or die if necessary to protect you."[77] (They knew just what Wylie wanted to hear. I have found no evidence that Mexican field workers ever placed themselves in the line of fire to save foreign oilmen.)

The test came in 1914. When word spread that the U.S. Marines had landed at Veracruz, the Americans vacated the oil fields in panic. No sooner had the supervisors and skilled workers left than the owners realized the dangers of abandoning the oil fields: runaway wells, burst storage tanks, broken down pumps, equipment theft, destroyed railway rolling stock, and fire. The Mexican workers missed two payrolls during the month's absence of their foreign managers. Yet they stayed on the job, maintaining the oil wells and storing the excess oil in earthen reservoirs. Concluded the American consul at Veracruz:

The small amount of damage which had been done to vast oil properties which were abandoned thirty days ago is largely due to fidelity of Mexican employees and generally speaking Mexican employees and servants have been very faithful to Americans who left them in charge of property in oil fields and in Tampico without funds for sustenance and in many cases with wages due them. The small losses is [sic ] remarkable under the circumstances and great credit is due such employees and servants.[78]

Occasionally, the foreigners overstepped the bounds of their workers' loyalty. These instances pertained to the individual Mexican's penchant to resist the undesirable aspects of proletarianization and preserve traditional individualism and mobility. The Mexicans in the oil industry, especially in construction, still clung to tarea (piecework) so that they could take off whenever they pleased. When fired with special indignity, the Mexican workman might round up several friends in order to lay an ambush for the offending foreign supervisor.[79] The foreign employers never did understand the Mexicans' ambivalent attitude about the material improvements, social welfare, and educational opportunities that the oil companies provided. Just when the company gave him benefits not to be found elsewhere, the individual might walk away from the job. "In spite of these [benefits], the workers show no particular loyalty to the company," reported one informant, "and are ready to sacrifice its interests both by rendering poor service, and by withdrawing without provocation."[80] Many a manager puzzled over the Mexican worker's propensity to preserve his independence. For the most part, the oil-field worker did not subscribe to labor militancy as a remedy to his problems. After all, he was not as dependent as his urbanized and proletarianized brethren at Tampico. He merely took off for his piece of land.

The refinery workers, however, were different. They depended on factory wages and were more proletarianized. Therefore, they suffered acutely from the greatest problem confronting urban workers during the oil boom: the cost-of-living rise that afflicted the Mexican economy beginning in 1914. In part, this economic condition obtained throughout the Atlantic world during the First World War, when the arming of the European nations, at the same time that the best workers were conscripted to fight the war, drove commodity prices sky-high. Most Western economies, including those in the Latin Americas, remained at full employment. But rises in the price of foodstuffs and consumer items outstripped wages. Workers throughout the Americas, therefore, threatened additional disruption of the economic system. They demanded higher wages and mounted work stoppages in order to gain some relief from the rising cost of living. Strikes broke out in Buenos Aires, Santiago, Lima, São Paulo, and Mexico City.[81]

In Mexico, the Revolution compounded the economic stress. After the most violent phases of the Revolution had subsided, experts surveyed the agricultural destruction. The population of livestock in

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Mexico had been reduced by as much as 60 percent. Veracruz, home of the oil industry, did not escape this disruption (see table 12).

The squeeze on workers' pay also affected the oil industry, but the owners were reluctant to raise wages. They reasoned that once wages were raised, they could not be reduced later when the cost-of-living crisis subsided. Instead, they preferred to increase the nonmonetary benefits like restaurant and company store privileges. Inflation of the Mexican paper peso, nonetheless, threw their pay policies into disarray, forcing employers to combine paper currency, Mexican silver, and American dollars.[82] El Aguila's managers despaired that they could contain worker unrest when the value of the American dollar too began to slip. By the end of 1916, they were finding that the workers would no longer accept their salaries half in silver and half in dollars. The discount on American currency was nearly 15 percent. Mechanics, formerly paid five gold pesos per day, now would not work even for seven pesos. The managers worried about what action the workers might take when the dwindling supply of silver currency dried up completely.[83] What did the workers do? They fought back. Nothing in their labor traditions, neither the outward appearance of servility nor the government's occasional use of repression had taught Mexican workers to accept as final such deteriorating conditions. To the contrary, they had learned that their demands, petitions to the state, and strikes often succeeded in yielding some relief. Oil workers at Tampico were to encounter remarkable successes in this regard, partially because the Mexican Revolution had fostered propitious developments in labor organization and had conditioned the state to be receptive to labor demands.

Just Equilibrium Between Opposing Interests

In November 1911, when a Huasteca paymaster at Tampico was late in distributing the pay, several hundred workers nearly rioted. Four members of the rurales, the rural police force, helped calm the crowd. At the time, sixteen rurales had also been permanently stationed at the refinery of Waters-Pierce since a 1909 strike to prevent disturbances.[84] If there once might have been a cozy relationship between foreign owners and the state concerning the control of the working class, it was to come to an end with the Mexican Revolution. This monumental upheaval in the social and political life of the nation — despite the relatively lukewarm participation of organized labor — represents a critical watershed. Before the Revolution, labor had little juridical existence. President Porfirio Díaz and local politicians dealt with strikes and workers' demands according to custom, which in Mexico had always dictated the state's protection of the downtrodden. When ad hoc state patronage did not restore labor's place in the delicate social order, the Díaz regime applied coercion. Indeed, many of these attitudes toward the working class carried over into the post-Porfirian age.

But the Revolution made possible more significant changes. That is to say, the Revolution itself produced nothing for the workers; it merely offered them the opportunity to act on their own agenda. In Mexico, workers made their own changes.

First and foremost, the incessant competition among the elites over who was to control the state raised labor's political importance. Politicians sought support from the working class in order to outflank competitors. Worker organizations had always been involved in politics; yet much of their participation had been subdued and made unimportant during the long reign of Porfirio Díaz. The Porfirian order of the day was "much administration, little politics," removing opportunities for labor to insert itself into the political process. The Revolution occurred at a moment when the urban, industrial working class was now larger, approximately 16 percent of the economically active population of Mexico.[85] But the clout of the workers was much greater than their number. Although they did not make the Revolution — it had been fought by armies of rancheros and campesinos — the workers did help consolidate it. Holding the cities and collecting taxes in the ports became the paramount task of the new revolutionary government.

The state's need for their assistance, therefore, empowered the urban and industrial workers to advance their own agenda. And the agenda of the Mexican workers of the twentieth century was not unlike the artisan's goals of the late eighteenth: to be incorporated juridically into public life in order to assure the individual's security within the economic system.[86] Such a goal violated the tenets of liberal capitalism, because the incorporation of labor into the body politic greatly infringed upon the exercise of private property rights. But even under Porfirio Díaz, Mexico had been an imperfect adherent to liberalism. The desire to tether capitalism became even stronger during the Revolution. In the first place, it provided the bourgeois politicians with a tool to end the social chaos and rebellion from below. In the second place, collective action and social reforms proffered the working class a sense of security and place in society. Unfettered capitalist growth did not.

No sooner had the old regime fallen than the politicians recognized the central role of labor in the new. In 1911, the Madero government established the Office of Labor in order to mediate disputes and "harmonize" capital and labor. Huerta turned the office into a labor department. Later governments expanded the personnel of this new bureaucracy, in recognition of labor's expanded role in revolutionary Mexico and in an effort to extend political control over the industrial and commercial regions, like Tampico, located far from Mexico City. While Carranza was in power, the labor department acquired Constitutional powers of arbitration and established an office of federal labor inspectors in Tampico.[87] The labor bureaucracy served somewhat the same purpose as the petroleum office technocrats. The state expanded both agencies in an effort to gain command over two elements thought to have contributed to the unraveling of Mexico: the excesses of foreign capital and labor unrest.

For these reasons, politicians who sought control of the state openly attempted to win the hearts and minds of the urban and industrial workers. Inhabitants of Tampico, as an important petroleum export center, became particular targets of competing local, state, and national leaders — whether civilian or military. Huerta's new labor department in 1914 assisted the Gremio Unido de Alijadores to win a contract committing the company to hire its members only.[88] Huerta might have won them over. The workers there responded with passivity when Constitutionalist forces besieged the huertistas at Tampico — but then Tampico workers, except perhaps as individuals, did not fight for or against any revolutionary faction, ever. Nonetheless, when the constitu-

cionalistas took the city, they gained the workers' support by promising land reforms, the eight-hour day, a minimum daily wage of five pesos, and rent reductions.[89] (Urban workers supported land reform because it would presumably keep their country cousins down on the farm.) Carranza himself, however, repudiated some of the more radical promises of his subordinates. The first chief's tepid support of reforms did not prevent his military officers nor the state governors from mediating labor disputes in Tampico. As commander of northeastern Mexico during 1915, Gen. Pablo González involved himself in the negotiations of various labor organizations with El Aguila and the Mexican Light and Power Company in Tampico. González tended to favor Mexican workers in their disputes with foreign-owned enterprises. One of his staff officers even proposed forming "arbitration tribunals," after the Veracruz state model, in which representatives of government, industry, and labor would meet to settle disputes. Only in this way, said González's aide, could the government guarantee stability and gain the support of the majority of its citizens.[90]

General Cándido Aguilar also made initiatives for labor reform in the state of Veracruz. As early as 1914, he proposed state legislation that would have established the nine-hour day and a system of state inspectors and mediators. As governor, he later called for state labor legislation. By 1919, he presented a draft bill to the state legislatures. The state had an obligation to regulate capital and labor, he said, because the strikes that had been occurring since 1915 threatened to "disorganize the active life of the State." The proposed law would "put an end to the anarchy which reigned in the realm of labor." Since conflict between capital and labor was natural, Aguilar stated, this law would provide the "just equilibrium between opposing interest" and would "give to each his share."[91]

Wooing labor became the special objective of those politicians seeking office. Several labor leaders in Minatitlán, in fact, ran for public office. One member of the El Aguila refinery union in 1917 became a local deputy and another the municipal president. In 1919, the young Tamaulipas lawyer Emilio Portes Gil attended the convention of the state's labor organizations in order to help form the Partido Laborista Mexicano, which supported Obregón.[92] The popular general himself came to Tampico in March of 1920. From the balcony of the Hotel Continental, he spoke to a large crowd (fifteen thousand persons, most of them workers, the obregonistas claimed) in the Plaza de la Libertad. But the local commanders, Gen. Francisco Murguía and Col. Carlos S.

Orozco, both supporters of Carranza, took several of Obregón's entourage into custody for insulting the president. Seven pistoleros confronted Obregón in his hotel room.[93] Mexican politics of the time was a high-stakes game.