John Michael Hayes: Qué Sera, Sera

Interview by Susan Green

* François Truffaut: "To my mind, Rear Window is

probably your very best screenplay in all respects.

The construction, the unity of inspiration, the wealth

of details."

Alfred Hitchcock: "I was feeling very creative at

the time, the batteries were well-charged. John

Michael Hayes is a radio writer and he wrote the

dialogue."

—François Truffaut, Hitchcock

In a quintessentially quaint house with a white picket fence in rural West Lebanon, New Hampshire, seventy-five-year-old John Michael Hayes recounted the many vicissitudes of his personal and professional life, both in and out of Hollywood.

Fortune has alternately smiled and scowled upon him. When it came to his career, Hayes experienced the heaven and hell of Alfred Hitchcock. The four films they made together in a remarkably short period of time during the mid-1950s—Rear Window, To Catch a Thief, The Trouble with Harry, and The Man Who Knew Too Much (1956 version)—would seem to provide the defining moments of Hayes's résumé. But an initially harmonious working relationship turned sour. According to Hayes, Hitchock nurtured the fledgling screenwriter only to betray him ultimately.

Throughout a hardscrabble working-class childhood, during which he endured temporary disability, Hayes worked his way through the system on the strength of his writing skills. The first in his family to enter college, he spent summers as a newspaperman, at one point covering a police beat. A

promising entry into radio broadcasting was forestalled by the army, which drafted him during World War II. Later, calamity struck again in the form of a crippling illness.

After fully recovering, Hayes went west in the late 1940s. A job writing radio mysteries led to an offer to try his hand at screenplays for the motion picture industry. It also led to an association with Alfred Hitchcock, who had heard his radio whodunits and recognized a kindred talent.

In 1954, the first Hayes-Hitchcock collaboration was the elegant and witty Rear Window, replete with sexual double entendres that were bold for their time. It ranks as Hayes's masterpiece and one of Hitchcock's finest.

The Trouble with Harry, while sweetly improbable, is also full of funny, frenetic wordplay. The even more suggestive To Catch a Thief has that je ne sais quoi. (Remember the repartee from the picnic sequence that begins, "Do you want a leg or a breast?"). And although Doris Day lacks the blithe charm of Grace Kelly, the clever writing of The Man Who Knew Too Much, a remake of Hitchcock's 1934 film and the last picture that Hayes did with the director, manages to draw the viewer into a suffocating web of intrigue.

By the time the last of the Hitchcock-Hayes films was released in 1956, the partnership had crumbled. Apparently, Hitchcock had no desire to be known as a co-master of suspense. While the great director did not exactly stumble on alone—his carefully picked screenwriters were always crucial to his success—some critics think he never succeeded as sublimely as when Hayes was by his side. "In the quartet of films scripted by John Michael Hayes," Donald Spoto writes in The Dark Side of Genius: The Life of Alfred Hitchcock, "There is a credibility and emotional wholeness, a heart and humor to the characters that other Hitchcock films—like Strangers on a Train and I Confess before, and others after—conspicuously lack."

Qué sera, sera. Hayes went on to adapt Grace Metalious's small-town soap opera Peyton Place (New York: Messner, 1956). It was a prestigious and daring film in its day, with Hayes earning his second Oscar nomination for Best Adapted Screenplay. (The first was for Rear Window. ) And the film holds up fairly well, although it does not have the cachet of a Hitchcock production.

Hayes had a productive decade in the 1960s. Among the top directors he worked with, not always happily, were Henry Hathaway and William Wyler. Butterfield Eight, The Children's Hour, The Carpetbaggers, Harlow, and Nevada Smith were all distinctly high-profile adaptations. Hayes seemed to specialize in films about people with delusions of grandeur. At their best, some of those 1960s credits maximized his strengths, showing off resourceful characters, offbeat dialogue, superb plotting.

Then fate frowned on him once again. After a series of near misses—scripts commissioned but not produced—Hayes unwittingly secured a financial stability that would keep him from writing and limit his creative output in the latter half of the 1970s. And then, genuine tragedy—his wife's terminal

cancer and Hayes's own partial blindness from macular degeneration of the retina—transformed his life in the late 1980s.

Even so, in 1994, a new John Michael Hayes film—only his second original screenplay—emerged. Iron Will, a Disney adventure about a determined boy in a dogsled race, was a victim of rewrite mania. Yet perhaps its iron-willed hero could be seen as an alter ego for the writer who had battled his way back from an almost twenty-eight-year dry spell between screen credits.

While he, too, copes with cancer, Hayes has been teaching screenwriting at Dartmouth College. He worries that he has turned his frequent lectures on Hitch into a cottage industry. Thanks to Iron Will, he is once again fielding offers from Hollywood. Strange as it seems, one of them is for a sequel to Rear Window. One thing is sure: if this film is ever made, at least Alfred Hitchcock won't be around to claim credit for the screenplay.

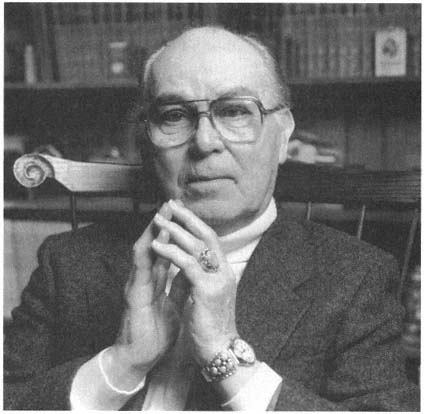

John Michael Hayes at Dartmouth, 1994.

(Photo by Joseph Mehling, Dartmouth College.)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Television script credits include the telefilms Winter Kill (1974), Nevada Smith (also coproduced, 1975), and Pancho Barnes (1988).

Academy Award honors include Oscar Nominations for Best Adapted Screenplay for Rear Window and Peyton Place.

Tell me how you got into journalism.

I was eight when I started writing. At fourteen, I started writing for money. I was born cross-eyed and had many operations. I lost two and a half years of

school, between second and fifth grades. I had ear infections that came as a result of my eye problems, so I had nothing to do but read. I went door-to-door, asking neighbors for books. I read Shakespeare, religious philosophy, history. I became word conscious, which led to a fascination with the process of writing. I knew this was the world that I wanted to be in.

I later worked on school newspapers and began sending items to local newspapers when I was twelve, thirteen, fourteen. I turned the money over to my father. Anything I could bring in helped. My father was a song-and-dance man in vaudeville, who went to work in a factory as a tool-and-die maker but lost his job during the depression. He ended up on the WPA [Works Progress Administration]. My grandfather had the oral tradition of Irish storytellers.

We lived in State Line, New Hampshire—population fifty-two. When we moved to Massachusetts, I was editor of a Boy Scout newspaper. Then, during high school, I wrote for the local paper, the Worcester Telegram, for ten cents a column inch. But I wrote so much I was making more than the regular reporters, so they put me on salary. At sixteen, I was hired by the head of the Associated Press and went to Washington, D.C. My column was "A Young Man Looks at His Government." I got ten dollars a day. Then the Boston Globe called . . .

I was able to fulfill my dream of going to college. No one in my family ever had. I had scholarships and I worked. I attended the University of Massachusetts, then called Massachusetts State College. In the summer, I would go back to the newspaper business. I had a police beat and saw the arrest process, went out on ambulance calls, covered homicides and suicides. Later, that gave my writing a frame of reference, because I'd seen a lot of the criminal side of life. I was on firm ground. It wasn't an alien world.

How and why did you make the transition to film?

After college, I could have gone on with academic work at Duke University, gone back to the Worcester Telegram or to the AP. I chose a scholarship from the Crosley Corporation in Cincinnati to learn broadcasting at a radio station. That led to writing daytime serials for Proctor and Gamble. Then I was drafted into the army for four years during World War II. I never went overseas or into battle, because I only had one good eye. They assigned me to special services, putting on entertainment for the troops at camps in California, Oregon, Missouri. Then, I ended up as a medic in the infantry.

After being discharged, I developed rheumatoid arthritis and was in bed for a year. It took me ten months to walk again. I had to use two canes.

I had little money, but I hitched to California in 1948 and found a job at CBS Radio the day I arrived. I wrote for Lucille Ball's My Favorite Husband and some suspense shows. Then, in 1951, I started writing B pictures for Universal.

The first of those was Red Ball Express. Didn't the director, Budd Boetticher, become a matador or something?

(Laughs. ) He was a roommate of John Kennedy at Choate. He came, I gather, from a social, rich family. He went to Spain and became a bullfighter. On the set, he used to bring his bullfighting cape and do veronicas and other things that bullfighters do. He was a very pleasant, easygoing guy. He was a lot of fun.

At this time, when you were starting out in the early 1950s, were there people who showed you the ropes?

There was a writer named Borden Chase, who did Red River [1948] and other action pictures.[*] He helped me out a bit, but the rest of it, really becoming cinematic, I had to learn myself. I just learned as I went along. I used to haunt sets at the studios and watch everything I could. I took notes. And I made a lot of mistakes. Also Charles Schnee—actually, he and Chase wrote Red River together—gave me a lot of tips. He was at Metro [MGM]. He had a B-unit there.

Were you inspired or influenced by other writers?

Definitely. Preston Sturges and Dudley Nichols. I used to study their work. And I liked Philip Barry's plays, the swing of his style.

About two years into your B-movie career, you met Hitchcock?

Yes. I had worked on a radio show called Suspense, which was a half-hour drama. Then I worked on The Adventures of Sam Spade and a number of other radio detective shows. He used to listen to them. He heard my name all the time. That's really what got him interested in me, because I doubt if he had gone to see War Arrow or Red Ball Express or anything else. So he inquired about me. It turned out we had the same agency, MCA, but we were in different departments. He gave me a tryout, and it stuck. He needed a writer for Rear Window, so I went from B movies to A movies overnight.

How did that all come about, the decision to make Rear Window?

Paramount found Rear Window. Hitch had left Warner Brothers and was looking for a home. And Paramount said if he could get a screenplay out of a Cornell Woolrich story, they would make a deal with him. They gave him a collection called After-Dinner Story, by William Irish [Philadelphia and New York: J.B. Lippincott, 1936], a pen name of Cornell Woolrich. Out of about five or six stories, he liked "Rear Window" and brought me in on it.

I understand the Grace Kelly character was your own idea.

* Borden Chase, born Frank Fowler in Brooklyn in 1900, was a novelist and scriptwriter best known for rugged adventure and western stories for directors such as Raoul Walsh, William Wellman, Anthony Mann, and Howard Hawks. His credits include Winchester '73, The Far Country, and Man without a Star. Chase's novel The Blazing Guns on the Chisholm Trail provided the story basis for Red River; he cowrote the screenplay with Charles Schnee. His television work included pilot episodes for the Daniel Boone and Laredo series. See Jim Kitses's interview with Borden Chase in The Hollywood Screenwriters, ed. Richard Corliss (New York: Avon, 1972).

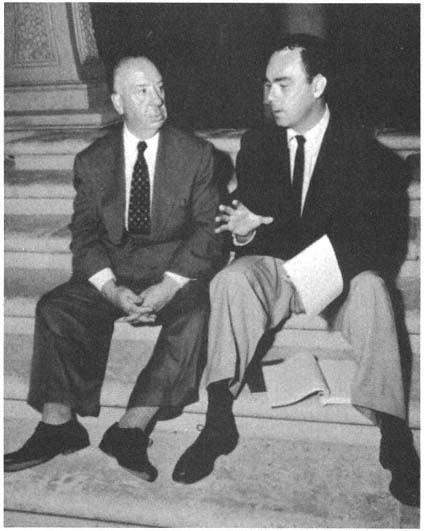

"From B to A movies overnight": Alfred Hitchcock conferring with John Michael Hayes.

There was no girl in the original. I created the part. Hitch had done Dial M for Murder [1954] with Grace Kelly, and she was beautiful in that film; but there was no life, no sparkle there. He asked me what we should do with her for Rear Window, so I spent time with her for about a week. My wife, Mel, was a successful fashion model, so I gave Grace my wife's occupation in the film. The way the character posed, the dialogue—it reflected actual incidents in our life.

Were there tricks or techniques that Hitchcock taught you? Things you weren't doing in radio or in B movies?

I like to write dialogue. It's one of my skills, character and dialogue. Hitchcock, of course, grew up in silent films, and all those directors who did silent films have a tendency to rely on the camera as much as they can. And I caught some of that spirit. Hitchcock taught me about how to tell a story with the camera and tell it silently.

We used a long camera movement to open Rear Window. In The Man Who Knew Too Much, in the scene at Albert Hall with Doris Day and Jimmy Stewart, we had written some dialogue in case we needed it, but we didn't intend to use it if we didn't have to. Hitch, with his mastery, felt that without dialogue this whole final sequence where the assassination is about to take place—of a central figure from some nameless country—would be stronger. We discovered we didn't need the dialogue at all. But we wrote it protectively.

You incorporated so much clever, risqué banter in your scripts for Hitchcock, particularly Rear Window and To Catch a Thief. Was there a method to your madness?

Oh, sure. We had censorship in those days. So, if I could do it and make it amusing enough, I could get away with it. I used to do that on radio, on shows like The Adventures of Sam Spade. By the time they figured out what I was really saying, it was too late to censor it. I think suggestion is better. I'd rather say things through a literary device that's interesting than just say it out flat. So much of my dialogue is indirect, with layers of meaning, sub-rosa meanings. It's more challenging to write that way, and people remember the lines. Frequently, people came up to me for autographs, and they quote some of those lines from my Hitchcock movies.

Did you often write with specific actors and actresses in mind?

Certainly. I knew Grace Kelly was going to be in Rear Window and that Jimmy Stewart, if he liked the treatment, was going to play in it too, so I was able to write for them specifically. I wrote a part specially for Thelma Ritter if they could get her, and they did.

Later on, I knew Cary Grant was going to be in To Catch a Thief. He used to bring in material all the time, and the idea there was to delay him until it was too late to do it. But he did it in an amiable, enthusiastic way. He was full of ideas, always wanted to improve things; it wasn't because he didn't like what was there. Of course, sometimes the studios made their own [casting] deals for their own reasons. But they would ask my opinion.

You really seemed to specialize in adaptations. Over the years, only two of your screenplays were originals. What were some of the other sources for your Hitchcock films?

After Rear Window, the next one was a book by David Dodge about adventures on the Riviera [To Catch a Thief (New York: Random 1952)]. We did To Catch a Thief out of that. After that, it was a remake of The Man Who Knew

Too Much that Hitchcock did in the early thirties in England. And The Trouble with Harry was a book by an English writer, Jack Trevor, whom he admired. Generally, studios bought properties and looked for a writer.

Was Rear Window a good first experience with Hitchcock?

That was my first A picture with a big director, and I was so keyed up. I didn't enjoy it as much as I should have, because I was worried about everything. Yet it turned out well. We worked beautifully together.

Your next film was The Trouble with Harry. Tell me a little about shooting that on location in Vermont.

We had a lot of trouble with The Trouble with Harry. We wanted autumn foliage, so we did background shots. Then a big storm hit, and the next day, no leaves were left on the trees. We took thousands of Vermont leaves back to Hollywood and plastered them on California trees in the studio. Many exteriors were shot in California and interiors shot in Vermont.

Shirley MacLaine had just gotten married the night before she showed up on the set. I remember Hitch saying, "There goes the picture." He felt that this was going to be her honeymoon, so her mind would not be on the work. It was her first movie and her first marriage.

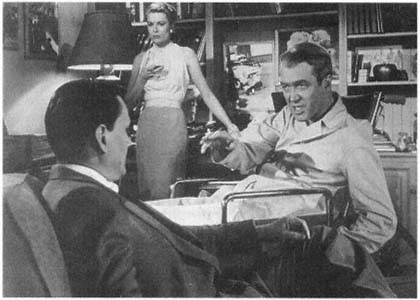

"Everything fit into place like a jigsaw puzzle":Wendell Corey (back to camera), Grace

Kelly, and James Stewart in Rear Window , directed by Alfred Hitchcock.

Rear Window was shot in the studio, but after that, you and Hitchcock seemed to be all over the map.

To Catch a Thief was on the Riviera. I took Grace Kelly to the casino to learn how to play roulette. She ended up not only winning money at the table—no great amount—but she won Monaco! She wanted to see the palace grounds, so I asked for permission; and she went and met Prince Rainier. I told her that I'd heard he was a stuffy fellow.

The Man Who Knew Too Much was made in Morocco and London. Hitch and I talked about doing other screenplays set in South Africa and Brazil. He had ideas of places he wanted to go to. We never made any, of course. He'd consider exotic locations whenever he could. Not only would he make a good film, but he'd also have an adventure.

What was Hitchcock like on a day-to-day basis?

His whole life was motion pictures; there didn't seem to be much else in it. He just loved what he was doing, and he transmitted that feeling to you, rather than hovering over you like a giant genius. He was encouraging. He used to say, "It's only a movie. Don't worry about it, just do your best, and let the public decide." Hitch was humorous and relaxed on the set. We'd go to dinner or lunch, but in no sense was I his personal confidant. He used to go over his early pictures and tell me how he had solved problems.

But then friction began to develop between you and Hitchcock. Did it start while you were in the south of France shooting To Catch a Thief?

I don't recall any real problems then. I think the worst fight we ever had was over the ending of To Catch a Thief. We had different ideas. I wrote twenty-seven different endings and still don't like the one that was used. We had a couple of slam-bang script fights. Still, we got along fine until I got too much press.

When we went to Paris for the premiere of To Catch a Thief, I was getting mentioned everywhere—they value writers in Paris—so I was promptly banned from all public relations events. If I was mentioned in the fourth paragraph of a story, that was okay but not in the first or second. I was becoming known for my dialogue and characterizations. They even talked about "the Hitchcock-Hayes fall schedule" in either Variety or the Hollywood Reporter.

When you show up in the same sentence—Alfred Hitchcock and John Michael Hayes—that was more than he could bear. He wanted to be the total creator: Alfred Hitchcock Presents. Hitch was so unkind about giving credit.

In an interview he did with Francois Truffaut years later for example, Hitch tried to make it seem as if he had written the screenplay for Rear Window. I heard about that too late; I tried to contact Truffaut, but he had died. I did a sixty-five-page treatment of Rear Window that Jimmy Stewart committed to, that Paramount committed to. I had met with Hitch once or twice. He had nothing to do with the writing.

I was nominated for an Oscar. When I won the Edgar Allen Poe Award [for Rear Window ], the first time it was ever given for a movie, I showed Hitch the ceramic statuette, and he said, "You know, they make toilet bowls out of the same material." Then he almost pushed it off the end of a table.

People believe he did everything. They just don't pay attention to the credits. Hitchcock had some big writers on his films, but you would never know it: Robert Sherwood [Rebecca, 1940], Samson Raphaelson [Suspicion, 1947], Thornton Wilder [Shadow of a Doubt, 1943]—Pulitzer Prize-winning playwrights—Maxwell Anderson [The Wrong Man, 1956]. Starting with Rear Window, I began to get a great deal of attention. Critics focused on it, and pretty soon, I was being linked with him. That was my undoing. Four in a row, and then we parted because I was being too identified with him.

It was during The Man Who Knew Too Much that Hitch turned on me. He insisted we put the name of a friend of his on the picture—Angus MacPhail—who had done none of the writing.[*] Hitchcock was paying me too little to begin with. On top of that, he wanted me to do the next script for free, something he owed Warner Brothers called The Wrong Man. He said, "If you don't do this, I'll never speak to you again." When I refused, he said, in essence, Let's see how far you go without me, kid.

But you did go far.

Yes. On my next project, Peyton Place, I got twice as much money as for all four Hitchcock pictures together.

Did you realize all along that you were being underpaid by Hitchcock?

My agents told me to be quiet and do the work, that it would be worth money in the future. But they were, of course, in Alfred Hitchcock's corner, more than in mine. So they didn't encourage him to raise my salary. When I left, the offers came in, and the money was big. So what I did get was a diploma from Alfred Hitchcock University, which was valuable.

Hitchcock's advisers asked him when his pictures got into trouble—on The Birds [1963] and Marnie [1964] and Torn Curtain [1966] and Topaz [1969]—to bring me back. But he never would, because it was an admission that he needed me, and he'd never do that. Those pictures didn't have the characterizations, the believability. They didn't have the fun. The films we made together, people call it his golden period. It was a tragedy. We were a great team.

* Angus MacPhall received co-credit for the 1956 version of The Man Who Knew Too Much. A British writer who started as a titlist in the silent era, he functioned as a story editor at Gaumont and Ealing studios, and collaborated on scripts including Whisky Galore (aka, Tight Little Island ). Among his other screen credits are two other Alfred Hitchcock films—Spellbound and The Wrong Man.

Apart from making more money, what was life like for you after Hitchcock? You were nominated a second time for an Academy Award with Peyton Place, which got nine nominations altogether.

Fortunately, I had a successful picture in Peyton Place, which showed that I could get along on my own, that it wasn't just Alfred Hitchcock that made me a good writer. I could do other things.

Peyton Place and Rear Window are my favorite films. Rear Window came out so well: everything fit into place like a jigsaw puzzle. Technically, it was more polished. But Peyton Place was emotionally satisfying. The relationship between Mark Robson and myself was marvelous. He was very creative and helpful. I had a small-town New England background of my own, and I understood the setting and the people and the patois and the feelings.

What did that mean in the evolution of the screenplay?

I just felt comfortable with the material. I tried to tell the story of the difficulty adolescents have passing through that invisible pane of glass as they become adults. I examined the turmoil they go through, especially in the town of Peyton Place. I was sympathetic to these young people. The first draft was nearly three hundred pages, and it took eight drafts to finally boil it down. I had little bits of my own philosophy woven in—I always do that. I drew on my

Diane Varsi (left) and Lana Turner in Peyton Place , directed by Mark Robson.

own experience of living in two small New Hampshire towns. It was not an alien land to me. I could see the town in my mind. I could feel it.

The hard part, of course, was to get over the censorship hurdles; we had to imply things. Everybody had read the book, so we couldn't disappoint them—without offending the censors and without offending the other countries in which it would be seen. Getting the Catholic Church's Legion of Decency seal was probably the most difficult thing. People felt it was a book that couldn't be made into a picture. We had to make it acceptable but entertaining and good. And the Legion didn't change a line. The man in charge, Monsignor Biddle, told me, "John Michael, you've done it!" He was a jolly fellow, reminded me of Barry Fitzgerald.

Weren't there also some funny location problems on Peyton Place?

Yes. We thought Vermont would be easy to film in. We knew a lot of officials in the Vermont Development Commission. However, the book was very scandalous. It shocked the whole world. It had been banned in Boston and every Catholic country. Despite that, it sold ten million copies—at that time, more than Gone with the Wind. A Vermont legislator stood up and pledged to pass a law against having Peyton Place filmed in his state. It was also kept out of Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Connecticut. For a while, we thought we'd have to do it in Oregon or Washington. But we contacted Senator Margaret Chase Smith in Maine. She got word to Governor Edmund Muskie, and he loved the idea. He told us, "Maine is yours!" But when we needed some autumn foliage, 20th Century-Fox borrowed Paramount's Vermont outtakes from The Trouble with Harry!

After Hitchcock, what was it like to work with other legendary directors? I'm thinking of William Wyler and Henry Hathaway.

All famous producers and directors have enormous egos. And it was difficult to work with some of them. Wyler was the most difficult of all.

More so than Hitchcock?

Hitchcock and Mark Robson were the easiest directors. They were amiable and easy to get along with. Wyler and Hathaway were not. They wanted their viewpoint told instead of yours. I don't know why they hired me and paid me all that money and then insisted I do it their way. We had many script fights.

Wyler was the most difficult director ever. He would not let you sit down and really write. Every ten pages, you had to turn them in, discuss, analyze them sentence by sentence, word by word. You could never get into—at least I couldn't—a creative flow. You kept getting interrupted. We did rewriting and rewriting and rewriting, which was ridiculous.

I had a similar problem with Henry Hathaway. He wanted to be part of every page. I prefer to start a screenplay and go through the whole first draft in one fell swoop. To get all the emotion, color, drama, melodrama, purple prose, and everything else that I can put into a story. Because I know that, during subsequent script conferences with the director and the stars, many things

get leeched out of it. So I want to put as much as I can into the first draft. I, therefore, have to be given my head, instead of writing a few pages and then having a conference, and writing a few pages and having another conference. It ends up that you don't write the kind of picture you want to write, and the director never gets a chance to see what you can do, because he's imposing his will on you constantly. When I argued with Henry Hathaway about Nevada Smith, I inevitably lost. But at least you've got to put up a good fight.

In the case of Mark Robson, I did Peyton Place completely before he read it. And, therefore, our conferences were concerned with cutting it down and trimming it and making it workable, rather than have him participate in the creative aspect of writing it.

As for Hitchcock, he let me write on my own, and then we conferred afterwards. We had some conferences, but he didn't go over pages. We'd sit and discuss the thing in general. I'd do a first draft and a second draft; then, we would do a shooting script, and that's when he would break up the story into shots, specific camera angles. He'd draw sketches. If I had a film with two hundred shots in it on my first or second draft, we'd end up with six hundred, because he broke it down into every single camera angle. Hitch did not like to make changes. When we finished setting up the shots before the picture was started, he'd say. "The picture is made now. All we have to do is sit on the set and make sure they follow what we've worked out here."

Hitch would never change the script unless the writer agreed to it. Too many directors think just because they're a director they know how to write, and they don't. On The Carpetbaggers and Where Love Has Gone, Edward Dmytryk was tempted to come in with dialogue and write long speeches. Those directors who write on location and change things are the bane of writers, because you don't see what mistakes they're making until it's too late. You just can't improve off the cuff on the set, because you upset the whole build of the emotions and the texture of the picture. On location, things happen weatherwise or otherwise. But you work hard to get the script tight and right. Tampering with it is very dangerous, especially in a suspense story.

With an important director who has a long track record of hits and awards, it's hard to stand up for your viewpoint. Directors have a tendency to fall back on things that they're used to which are safe. If they hire a talented writer, they should let him write it and then discuss the directorial changes. That's the difficulty of working with extremely successful, older, talented, even brilliant directors.

I remember once telling Willie Wyler that he was wrong about something, and he took me around his office and he showed me every award he'd won—and he had many—and he read all the inscriptions. It must have taken him thirty minutes. Then he said, "Now tell me I'm wrong. What does all this mean?" And I said, "Well, those were things you've done in the past. I think you're wrong now."

Did you sometimes feel, in a strange way, justified to see bad reviews?

Yes. I once had a debate with a producer over a Gable picture, But Not for Me [1959]. After the preview, the producer said, "I wish I'd listened to you. You were right."

I've seen bits of some of my pictures when I wanted to run down the aisle and say, "No, no. That's not the way it's supposed to be." But other things that directors did surprised me and delighted me and made things more interesting. So you lose a little, you win a little.

I still remember a line from the review in the Los Angeles Times of War Arrow with Jeff Chandler and Maureen O'Hara, which came out in 1954: "The director struggled valiantly with the material given to him." That was an original story of mine—a true story—about Seminole Indians being moved from Florida to Arizona because they were rebellious. So they used them as scouts to subdue the Kiowa, and you had Indians against Indians. The review was so unfair. The director, George Sherman, took out four action scenes and replaced them with four talk scenes, which talked about the action but didn't show it. The studio heads at Universal later said, "We know what happened: It's not your fault."

Were you pleased with how The Children's Hour and Nevada Smith turned out?

Not at all pleased with The Children's Hour and somewhat disappointed with things that happened in Nevada Smith. Hathaway went on location and made changes in the script himself; then, he called me because he got into trouble. I had to fly down to Biloxi and try to straighten it out. Those pictures weren't as enjoyable as the others were, where at least I got to state my case in my first draft.

Was Lillian Hellman involved behind the scenes in The Children's Hour?

Willie Wyler was in constant contact with Lillian Hellman. Don't forget they had made another version earlier, in the thirties, and Lillian Hellman did the screenplay for that.[*] Wyler was very nervous about pleasing her, and she was a hovering influence over the whole thing. I never talked with her, but she wrote long letters to Wyler. He had another writer working on the film, who left before I came on. I myself would have been happy to leave. I wasn't happy at all with the atmosphere or the final result. At the end, I became ill. There were two scenes left. Hellman did them.

Tell me about Judith. That was a Lawrence Durrell piece . . .

Yes. Durrell was a brilliant English writer. He wrote an original story based on the time when Israel was trying to become a state. They had another writer on the project to begin with, and they were on location for months trying to

* The earlier film version of The Children's Hour was titled These Three (1938). William Wyler also directed this film from Lillian Hellman's adaptation of her play. The cast included Merle Oberon, Miriam Hopkins, and Joel McCrea.

Shirley MacLaine (center), Audrey Hepburn, and James Garner in a tableau from

director William Wyler's 1962 remake of Lillian Hellman's The Children's Hour.

shoot scenes. Danny Mann, for whom I'd done Butterfield Eight, persuaded me to come over and do a rewrite, which I did in eighteen days. They started shooting when I was on page 21, hoping it would come out all right. There was a lot of conflict over the film. It went way over budget. Sophia Loren was getting a million dollars to play the part—which was then remarkable.

A number of pictures I did were emergency rewrites. The pressure is always so great. Cast and crew sitting around, waiting to shoot. The studio has an enormous investment. They start shooting the first few pages. The same thing happened to me on Harlow. They started shooting in sequence and then cut each reel, doing sound and the music behind me. Once a sequence was done, it was set in concrete. We couldn't change anything. Later on, you couldn't balance the picture. The same thing was true on The Man Who Knew Too Much. We went on location when they only had a few pages of the script.

On these emergency rewrites, not only do you have only two to three weeks to do a script that they've worked on for months and months without solving the problems, but they're actually shooting what you're writing. I was able to write rapidly and considering the problems, it's remarkable how well some of these films came out.

Why would Hitchcock, who was always so prepared, begin shooting The Man Who Knew Too Much without a finished script?

Time moved faster than he realized. The things we'd finished, he shot first. Then I had to cable him, send pages to him every day. We did have an outline, and of course, we had the original picture, so he knew what he was going to do.

Did the people you worked with become friends?

Most of the relationships with stars were professional. I did socialize a little with Clark Gable. I visited Grace Kelly in the palace, my wife and I. Very interesting. It was only a year after she married Prince Rainier III, and she hadn't changed much; but the prince was the kind of person I didn't fully appreciate.

There were only a few writers who really entered the social whirl of Hollywood. You're leapfrogging from one picture to another. You don't maintain these friendships. I had a very exciting career, but there was always a lot of pressure, a lot of things had to be done in a hurry. The only exception was Hitchcock where, except for The Man Who Knew Too Much, we took all the time we wanted.

In the 1960s, there was such rapid social change in America. Did that affect your work for Hollywood?

Hollywood really didn't change much until the seventies. The sixties got a little more liberal. I didn't feel any disruption. I must say that I later wished I could have gotten away with things that would have made my films more real and adult. I was a dramatic innocent. I wasn't concerned with shocking people. I wasn't getting any message to do anything wilder in the sixties. Most of those breakthroughs came from independent productions, and later the studios followed along. Nobody said, "Let's get down and dirty." If we redid Butterfield Eight now, it would be a sexier picture. The book wasn't in front of the public's mind at the time the way that Peyton Place had been, so we didn't have any censorship troubles. We had a rape in Peyton Place, and we approached it carefully. I always worked from my own standards and tastes.

You did something like eleven pictures after breaking with Hitchcock but then, starting in the mid-1960s, nothing. Why?

I was very fortunate. Careers don't always last a long time. After 1965 and Nevada Smith, I did eight screenplays that, for different reasons, were never made. Two producers died. Two left the studios. One screenplay I did with Mark Robson fell apart for legal reasons. Another script I worked on for a long time with Irwin Allen got dropped because we couldn't get Air Force cooperation. There was another one that Paramount was going to do, but then they decided it was too expensive. I got paid for all of them, but for reasons that had nothing to do with quality of the writing, the projects were all dropped. With all the good luck I had before, I was having bad luck now.

From 1959 through 1969, we lived in Maine. It was a dangerous thing to do, because out of sight, out of mind. Perhaps it was an unwise move. I

wanted more of a rural, outdoor life. Eventually, we moved back, but I never enjoyed California.

Then, I signed a contract with Embassy Pictures, Joseph E. Levine's company, which he up and sold to Avco. Avco went out of the picture-making business and just stayed with distribution. But they had an ironclad contract with me, so I spent six or seven years as a vice president there, although I know nothing about distribution. I actually had a ten-year contract, which we condensed from 1975 until 1981.

They kept saying, "We're going back into making pictures," but they never did. I couldn't work for anybody else because there was so much money involved, and I had a family to support. I wasn't about to throw the job away in times when a whole series of pictures I'd written were being canceled.

When my wife, Mel, became ill with ovarian cancer, I retired because I had to take care of her. We moved to New Hampshire. We knew they had a fine hospital here. Dartmouth offered me a professorship.

I did some television things from New Hampshire. While Mel was in treatment in 1986 and 1987, I wrote a CBS-Orion picture called Pancho Barnes. I also did a four-hour version of the life of Indira Gandhi, but the company I wrote it for went bankrupt, and the political fortunes of India prevented it from ever getting made. I began a life story of Wild Bill Donovan, who worked for the OSS which later became the CIA. I stopped working on that in 1988 when my wife died. She was my muse, my catalyst. I wrote before I met her, but I wrote better when she was here. In 1987, I also began losing my sight. I'm legally blind now. My wife's gone, and my children and grandchildren are scattered all over the country. So there's a long black period in my life.

But suddenly, in 1994, there was another John Michael Hayes credit on the big screen, Iron Will.

I rewrote a story I'd done in 1986 or 1987, before I lost most of my vision. Friends believed in it and submitted it to Disney. It's about a dogsled race from Winnipeg to St. Paul. A boy who wants to go to medical school trains an oddball bunch of house pets and enters the race. McKenzie Astin stars as the young man who uses mutts instead of professional racing dogs, and he doesn't have a sled made by a master cabinetmaker. It's an adventure. Man against the elements, against impossible odds. Truly true grit and determination. Kevin Spacey is a reporter who sees beyond the race itself into the human drama. The idea came from a news clipping. It's an historical piece set in 1917.

With Iron Will, I finally sat down one day to write something for myself again, something that came from my heart. Most of my other films didn't express what I felt. I wrote the story and the screenplay. This one was supposed to be all mine. But then they brought in other writers to Disneyize it.

Are new offers coming your way as a result of the publicity on Iron Will?

Well, Disney inquired about doing another story with me, but we couldn't agree on the premise of it or on the way it was to be told. Warner Brothers

also submitted a story to me that I didn't want to do because it was too depressing. In the past year, with my cancer and chemotherapy, I've had a very low energy level. I've been ill a great deal, and I don't see very well anymore. But if a story came along or I thought of a story I liked. I would work on it.

And there's someone who wants you to do a sequel to Rear Window?

I was offered an absolutely monumental sum of money, half a million dollars, by the man who owns the rights, Sheldon Abenal of the American Play Company in New York. That money would help me in my old age. Hitch only paid me fifteen thousand dollars for the original Rear Window. You would either have to cast new people or set it in modern times, pick it up with their children or something. Tentatively, I was going to keep it in the same time period.

I don't know. Some pictures have a magic that's almost indefinable. Grace is gone. Hitch is gone. Jimmy's too frail. Wendell Corey's gone. Raymond Burr is dead. We couldn't recapture that kind of innocence. What could it possibly be?

But I've done a story, just in case.