Five

The Aspirations and the Hopes

The Greek Revival of Yoknapatawpha

To his grandest characters, as to Faulkner himself, the most favored architecture was the neoclassical, especially the local variants of the international Greek Revival, the symbol, even in decay, of what Faulkner believed were the better impulses of Southern civilization. The Greek Revival was a romantic, mid-nineteenth-century phenomenon, the latest in a long series of neoclassical movements that had begun with the Italian Renaissance in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. The evolution had become more florid in the Baroque and Rococo styles as they moved northward through France, Austria, and the German states in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Britain, and later America, were less touched by the Baroque and Rococo than by the earlier, less encumbered Renaissance modes. The greatest influence on British and American building was, in fact, the work of a single, late Renaissance architect, Andrea Palladio (1508-1580). In his penchant for orthogonal, domed structures, Palladio's models were arcuated Roman variations on trabeated Greek forms, an emphasis that would likewise permeate high-style British and American architecture into the early nineteenth century.

Constitutional government, argues historian Leland Roth, "was an experiment in applied Enlightenment philosophy which rejected monarchical absolutism and attempted to recreate the natural society in which it was believed men were meant to live. Thus architects correspondingly rejected Baroque-Rococo complication of form in search of a simpler architecture suggestive of the first civilized state of primal man." Since the founders of the American Republic, moreover, had "borrowed so heavily

from the form and terminology of the Roman republican government, it was natural that Roman architectural forms should be among the first used by American architects." Particularly in the work of Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Latrobe, and especially in the planning of the new national capital at Washington, an abstract version of Roman forms predominated. [1]

The revival in the mid-nineteenth century of simpler, purer, pre-Roman, Greek architecture was, on the one hand, a logical extension of the Roman Revival and, on the other, a reactive retreat from the Roman leanings of previous generations. It thus brought into sharper relief the affinities and differences between the Greek and Roman architectures of antiquity. In addition to the formal, geometric differences between Greek trabeation and the Roman amalgamation of trabeated and arcuated forms, there were cultural and contextual differences that further contributed to regional preferences for Greek architecture in mid-nineteenth-century America, especially in the rural South. While the general image of Roman building suggested urban juxtapositions, annexations, and collisions of forms, as in the Roman Forum, the chief image of Greek architecture was of serenely discrete structures, related to but interstitially separated from each other, as on the Acropolis in Athens. [2]

Further stimulated by the early-nineteenth-century Greek war of independence from the Turks, the Greek Revival was an international movement that permeated the western world, including all portions of the United States. Indeed, most Americans, north and south, who built or used neoclassical buildings were unbothered by archaeological distinctions between "Greek" and "Roman." Yet, to philosophically inclined Southerners, the appeal of Greek architecture was more than that of just a new aesthetic fashion. The predominantly rural social structure of the American South, the penchant for placing important buildings in relatively serene isolation, helped to contribute to the region's affinity for things Greek. Even in the twentieth century, Faulkner himself would tell a friend that he would love to go to Greece. All that we learned that's good comes from there .[3]

Aided by James Stuart and Nicholas Revett's seminal study, The Antiquities of Athens (1763), American pattern books, such as Asher Benjamin's illustrated Practical Home Carpenter (1830) recorded proportions and details of Greek orders and provided models and instructions that local artisans could develop. [4]

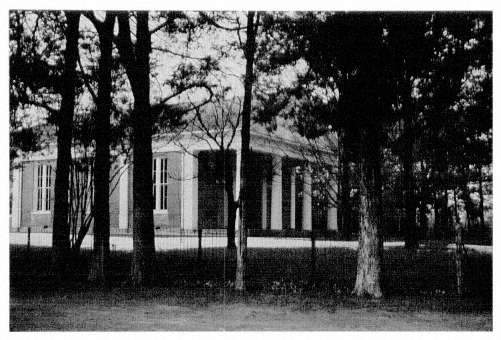

The finest Greek Revival building in Faulkner's Lafayette County was the Lyceum Building (1844-48) on the University of Mississippi campus, with its grandly over-

Figure 34

College Church, College Hill, Mississippi (ca. 1844).

scaled portico faced with six huge Ionic columns (Fig. 2). It was designed by the nationally renowned neoclassicist William Nichols (1777-1854), architect of the Mississippi State Capitol (1833-40) and the Mississippi Governor's Mansion (1836-42), both of which Faulkner would use and analyze in Requiem for a Nun . Faulkner admired but never mentioned the Lyceum in his work, probably because, significantly, in the parallel world of Yoknapatawpha the University was placed not in Jefferson but in the nearby town of "Oxford," where in reality it actually resides. This is one of several arguments for the often stated, though still underappreciated, contention that the "prototype" for Jefferson is a composite of several places and is at least partially based on Ripley, located some fifty miles northeast of Oxford, the same distance, approximately, between "Jefferson" and "Oxford."

A small but important Greek Revival building in Faulkner's personal life was the College (Presbyterian) Church (1846), in College Hill, Mississippi, four miles northwest of Oxford, an elegantly simple brick structure with a strong, Doric-columned portico (Fig. 34). After the slave gallery at the rear of the sanctuary was removed, two small, white outside doors remained as traces high up toward the ceiling of the portico facade, hanging as though suspended in space, the outside stairs accessing them having

Figure 35

First Lafayette County Courthouse, Oxford, Mississippi (1840; photograph, 1862).

been removed. Though Faulkner never used the church directly in his work, it was the scene in 1929 of his marriage to Estelle Oldham Franklin.

Still, the most significant building in all of Faulkner's work was the county courthouse, the symbol, he argued in Requiem for a Nun , not only of law and justice, but spiritually, psychologically, architecturally, the center around which life revolves: the focus, the hub; sitting looming in the center of the county's circumference like a single cloud in its ring of horizon, laying its vast shadow to the uttermost rim of horizon; musing, brooding, symbolic, and ponderable, tall as cloud, solid as rock, dominating all: protector of the weak; judiciate and curb of the passions and lusts, repository and guardian of the aspirations and the hopes; rising course by course during that first summer (Fig. 35). [5]

Though the name of the original architect has not survived, the Lafayette County Courthouse was built, and possibly designed, by the contractors Gordon and Grayson and was completed on January 12, 1840, at the then-sumptuous cost of $25,100. Faulkner later decided that in Yoknapatawpha, the designer of the building should be the same "French architect" who designed "Sutpen's Hundred," an analogous "grand design" in the private realm. In a crucial passage in Requiem for a Nun , Faulkner emphasized that of all the county's buildings, the courthouse came first, and . . . with stakes and hanks of fishline, the architect laid out in a grove of oaks opposite the tavern and the store, the square and simple foundations, the irrevocable design not only of the courthouse but of the town too, telling them as much: "in fifty years you will be trying to change it in the name of what you will call progress. But you will fail . . . you will never be able to get away from it ."[6]

Faulkner then linked the courthouse to the larger town and county, a strong example of his interest in urban design, an interest perhaps partially engendered by the fact that his maternal great-grandfather, Charles Butler, in the late 1830s surveyed and laid out the town of Oxford. The courthouse was situated in the center of the Square quadrangular around it, the stores, two-storey, the offices of the lawyers and doctors and dentists, the lodge rooms and auditoriums, above them; school and church and tavern and bank and jail each in its ordered place . (Fig. 36). Unlike the actual Oxford Square (Fig. 7), which had six roads leading from it—one each from the center of the north and south sides, one each from the four corners—Faulkner devised for the Jefferson Square the more elegant arrangement of four roads leading to and from the exact centers of the four sides of the courthouse: the four broad diverging avenues straight as plumb-lines in the four directions, becoming the network of roads and by-roads until the whole county would be covered with it . It was a reification, in the public realm of a frontier Mississippi town, of the ancient idea of the "grand design." [7]

In Requiem , in the construction of the fictive building, eight disjointed marble columns were landed from an Italian ship at New Orleans, into a steamboat up the Mississippi to Vicksburg, and into a smaller steamboat up the Yazoo and Sunflower and Tallahatchie, to Ikkemotubbe's old landing which Sutpen now owned, and thence the twelve miles by oxen into Jefferson: the two identical four-column porticoes, one on the north and one on the south, each with its balcony of wrought-iron New Orleans grillwork, on one of which —the south one —in 1861 Sartoris would stand in the first Confederate uniform the town had ever seen, while in the Square below the Richmond mustering officer enrolled and swore in the regiment which Sartoris as its colonel would take to Virginia . . . and when in '63 a United States military force burned the Square and the business district, the courthouse survived. It didn't escape: it simply survived: harder than axes, tougher than fire, more fixed than dynamite; encircled by the tumbled and

Figure 36

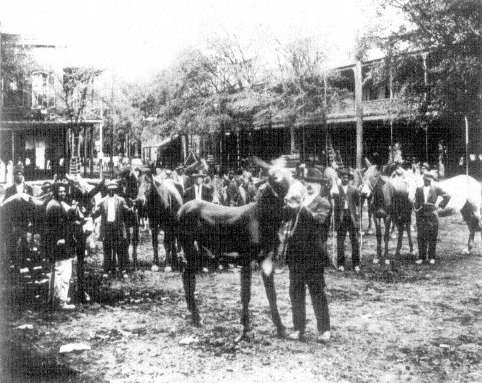

Courthouse Square, Oxford, Mississippi (late nineteenth century).

blackened ruins of lesser walls, it still stood, even the topless smoke-stained columns, gutted of course and roofless, but immune, not one hair even out of the Pans architect's almost forgotten plumb, so that all they had to do . . . was put in new floors for the two storeys and a new roof and this time with a cupola with a four faced clock and a bell to strike the hours and ring alarms; by this time the Square, the banks and the stores and the lawyers' and doctors' and dentists' offices had been restored . The actual postbellum courthouse (Figs. 37 and 94) was designed and built ca. 1870 by the firm of Willis, Sloan, and Trigg, Builders and Architects, who did virtually identical plans for two contemporary courthouses in county seats due north of Oxford: Holly Springs, Mississippi, and Bolivar, Tennessee. [8]

Though Faulkner allowed the Jefferson courthouse to survive the war more intact than did its actual Oxford counterpart, and though Jefferson's Square opened to four streets instead of Oxford's six, the similarity of the two environments, both before and after the war, was an exceptional merger of the actual and the apocryphal.

Figure 37

Second Lafayette County Courthouse, Oxford, Mississippi,

Willis, Sloan, and Trigg, architects (ca. 1870).

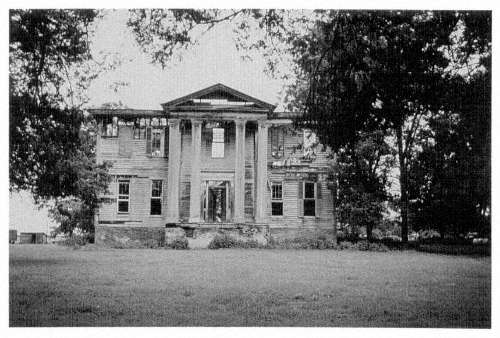

The greatest quantity of neoclassical buildings, and after the courthouse the largest and finest, was the impressive cluster of Greek Revival houses of the Yoknapatawpha gentry, symbols for Faulkner of a quality of life and a quality of people he admired and emulated despite their personal flaws and despite the flaws of the society that reared them—based upon slavery and a black-white caste system. Just as Jefferson and Yoknapatawpha were amalgamations of several actual Mississippi towns and counties, the homes of Faulkner's characters were composites of actual houses on the north Mississippi landscape.

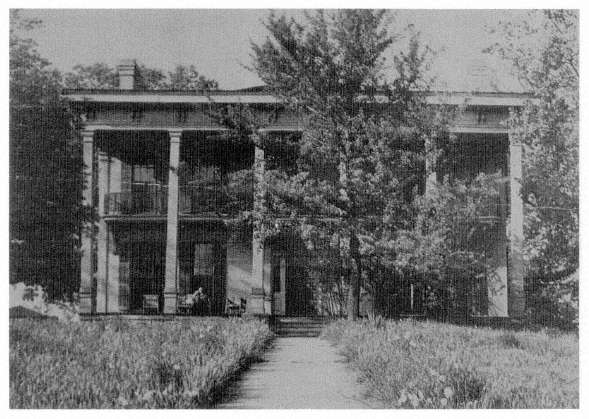

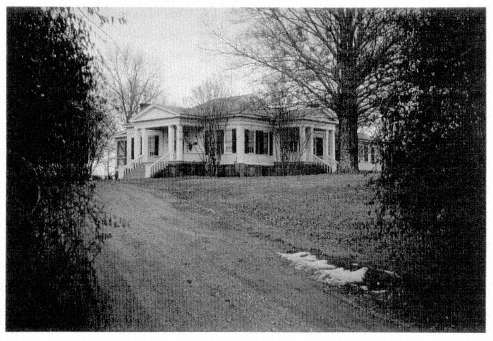

The most typical regional form of the neoclassical house was a nearly square or rectangular one- or two-storey box with a relatively small four-columned porch on one or more sides. Above the front door, and sometimes a side door, there was usually another door in the second storey leading onto a small balcony. Window shutters, usually painted dark green, were functional screens against sun and weather as well as decorative counterpoints to the standard white walls. Other ornament on the generally chaste buildings might include a wrought-iron railing for the second floor balconies (Plate 6 and Fig. 38). On either side of the central hall lay the parlor, library, dining room, and, in one-storey houses, bedrooms. The central stairhall in two-storey houses led to upstairs bedrooms. In the middle third of the nineteenth century, this mode was especially popular in Mississippi, Alabama, and Tennessee. Oxford and Lafayette County, during Faulkner's lifetime, contained over a dozen extant examples of this type of house, as well as several houses of even grander pretensions, marked by a six-or eight-columned portico extending across the entire front.

The architect-builder in antebellum Oxford most associated with the four-column type was William Turner, a talented though untrained designer who had come to Oxford as a young man sometime around 1840 with his parents, Samuel and Elizabeth Turner, from their home in Iredell County, North Carolina. Turner was the documented designer-builder of several such houses and the possible architect of all or most of the others. If he was not the actual designer for every house of this type, his work could have served as a model for structures by other builders which bore a remarkably close family resemblance. Antebellum houses in this mode in Oxford included the homes of the Craig, Eades, Howry, Shegog, Neilson, Carter, and Thompson families, as well as two successive residences William Turner built for himself. Plantation houses in the four-column mode were built in the county for various owners, including the Price, Wiley, Shipp, and Jones families (Plate 5). [9]

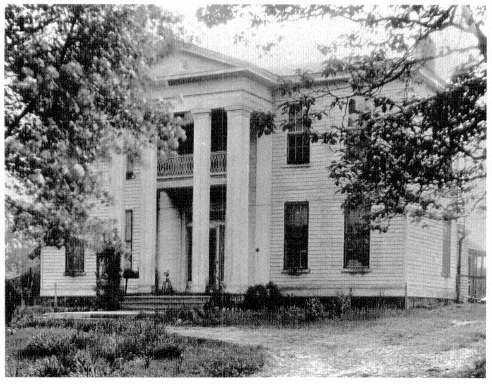

At least five houses, known or believed to have been designed and built by Turner, were imposing edifices on the Oxford townscape. Two of these, the Carter-Tate and

Figure 38

Carter-Tare House, Oxford, Mississippi, attributed to William Turner, architect (1859).

Neilson-Culley homes, were designed in 1859, with two-storey, four-column porticoes on the front and one side (Fig. 38 and Plate 6). The builder of one of these, Dr. Robert Otway Carter, was the great-great-grandson of the legendary Robert "King" Carter, who in the 1740s, as one of the richest men in Virginia, owned one thousand slaves and three thousand acres of land. Faulkner may have known that "King" Carter allegedly aspired in his grandiose plantation house "Corotoman" to "rival or surpass the Governor's Palace" in Williamsburg, just as Faulkner would later have Thomas Sutpen decree in Absalom, Absalom ! that "Sutpen's Hundred" should rival or surpass the Yoknapatawpha courthouse. Like the actual Corotoman, Sutpen's Hundred would ultimately succumb to destruction by fire. [10]

It was also Turner who likely designed, for the merchant William S. Neilson, a virtual twin of the Carter house. While the latter passed into the family of the Oxford merchant Henry L. Tate and fell in the twentieth century into picturesque ruin before it was finally razed, the Neilson house in the twentieth century was acquired by the prominent Oxford physician John C. Culley, who with his wife, Nina Somerville Culley, impeccably restored and maintained it. Though Faulkner and Culley had an occasionally strained personal relationship, the two couples were socially amicable, and Faulkner knew the house well, as he knew other buildings by Turner, for example, the house, later named "Cedar Oaks" (1858), that the architect designed for himself on North Lamar Street, two blocks from the Square. [11]

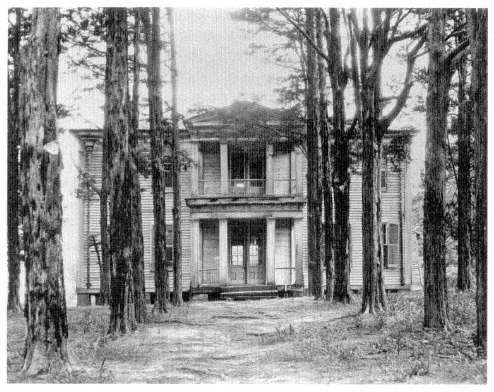

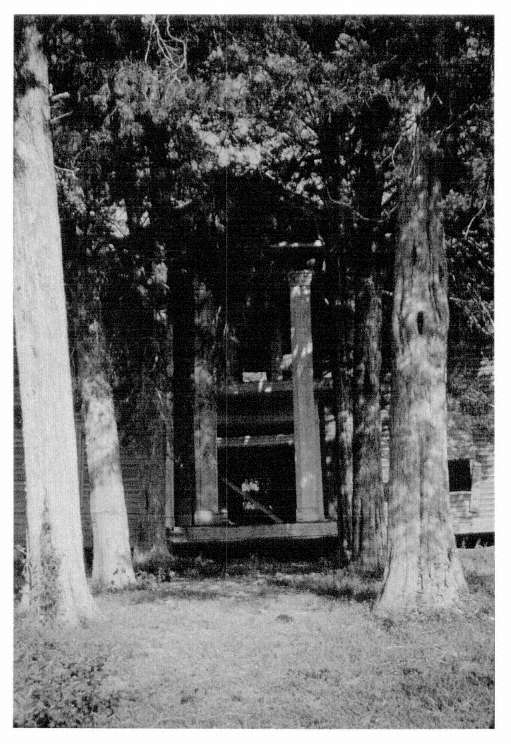

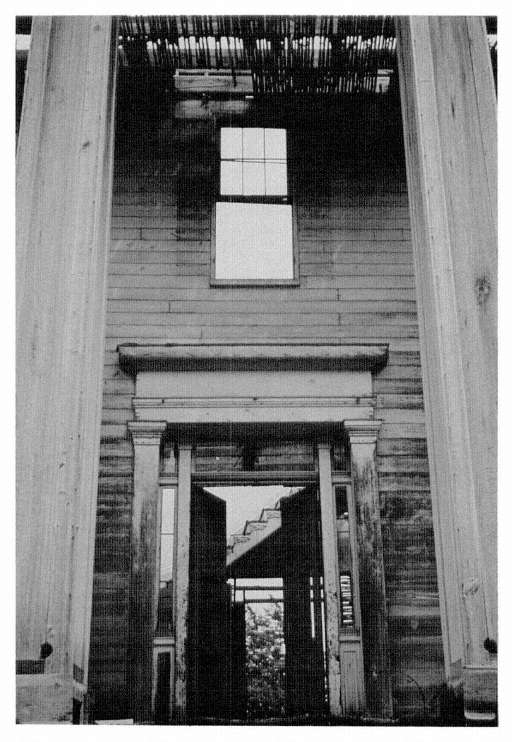

For William Thompson, the brother of the eminent Jacob Thompson, secretary of the interior in President James Buchanan's cabinet, Turner designed his usual two-storey, four-column mansion with the intention that it should replace two smaller, juxtaposed houses, the earliest of which was built ca. 1837 by John D. Martin, one of the founders of Oxford. With the outbreak of war in 1861, only the front half of the new structure had been completed (Figs. 39 and 40). After the war, Thompson's financial condition rendered him incapable of finishing it as planned, and the older, attached structures at the rear were not demolished. Thompson did, however, after United States troops burned the first county courthouse, acquire and surround his house with the wrought-iron fence that had surrounded the courthouse. Faulkner may have known that, like a tree at the Isom Place, north of the Square, the magnolias on the Thompson lawn were brought as seedlings from South Carolina, a symbolic act that Faulkner would later incorporate into his treatment of the Sartoris house. [ 12]

One of Thompson's daughters, Lucretia, called Lula, married Dr. Josiah Chandler and moved with him and their growing family back into the family home to care for her aging father. In 1893, the last of the Chandler children, Edwin Dial Chandler, was

Figure 39

Thompson-Chandler House, Oxford, Mississippi, attributed to William Turner, architect (1860).

Figure 40

Thompson-Chandler House.

Figure 41

Elma Meek House, Oxford, Mississippi (ca. 1879).

born mentally retarded, a condition known to young William Faulkner. In fact, according to Williams's brother John, the Faulkner boys often noticed Edwin behind the iron fence when they walked by the house. William became upset when neighborhood children taunted Edwin cruelly. Indeed, various observers have surmised that Faulkner based the character Benjy Compson, in The Sound and the Fury , on Edwin Chandler. Because of the affinities between the actual and the apocryphal, social and architectural, the Thompson-Chandler house by the mid-twentieth century was often referred to in Oxford as "the Compson house." [13]

The Turner-designed house that Faulkner knew best was one of the architect's earliest Oxford commissions, the Shegog Place (1848), across the Taylor Road from the grand Greek Revival home of Jacob Thompson, which was destroyed by Federal troops in 1864. After their marriage in 1929, the Faulkners lived for two years in an apartment on University Avenue in the handsome postbellum neoclassical home of Elma Meek, the Oxford dowager who suggested the name "Ole Miss" for the university yearbook, a name subsequently applied to the institution itself (Fig. 41). In this house Faulkner wrote Sanctuary and several important stories, including "A Rose for Emily." In 1930, with his first substantial royalties, Faulkner purchased the dilapidated

Figure 42

Sheegog-Faulkner House, Rowan Oak, Oxford, Mississippi, William Turner, architect (1848).

Figure 43

Avant-Stone House, Oxford, Mississippi (mid-1840s)

Shegog residence and lovingly began to restore it, getting to know the building and the construction process intimately as he worked with the carpenters in its slow resuscitation (Fig. 42). Another nearby structure of the four-column type was the Howry-Wright house on University Avenue, begun ca. 1837, probably as a modest structure that evolved, in the prescribed way, into a neoclassical house. Faulkner may have known, since he would later use the idea in his work, that, as at other houses in the region, Union troops dug up the front lawn in search of silver and other valuables purported to be buried there. [14]

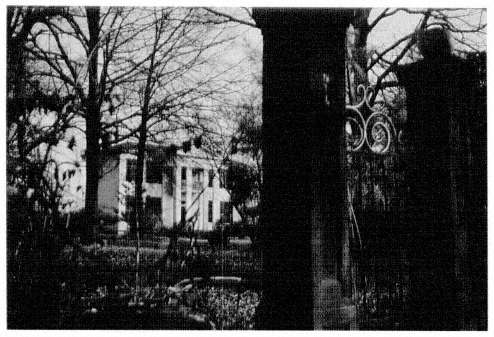

The grandest house in Oxford that Faulkner knew well was the Avant-Stone mansion, built in the early 1840s on the Old College Hill Road near the northwest edge of town by Tomlin Avant, the youngest son of a prosperous Virginia family who had, nonetheless, arrived penniless in Oxford in the late 1830s (Fig. 43). The name of his architect has not survived; if it was William Turner, it was a departure from his usual four-column prototype. Its similarity to several houses in Mississippi and Alabama by the famed William Nichols suggests that the architect of the Lyceum, who spent several years in Oxford in the early and middle 1840s,could have been Avant's architect. By building a great house, on borrowed money, Avant hoped to purchase instant status and ultimately prosperity in his adopted community, and he therefore entertained lavishly in his large, white, two-storey residence with its six-columned portico running the entire front length of the house. The impressive doorway from the upstairs hall duplicated the scale of the main, first-floor entrance as it opened onto a shallow, wrought-iron balcony. After Avant went bankrupt, the house went through several owners, including University of Mississippi Chancellor Edward Mayes and his famous father-in-law, senator, presidential cabinet member, and Supreme Court justice, Lucius Quintus Cincinnatus Lamar. By 1892, the house was vacant and in ill repair when the lawyer, James Stone, purchased and restored it. There, his son Phil, Faulkner's closest hometown friend and mentor, grew up as a child and continued to live as an adult, enjoying, among other things, the remnants of the vast library left behind by Mayes and Lamar. It was a house, and a library, that Faulkner knew intimately before it burned to the ground in 1942. [15]

Similar to the four-column Turner-designed homes in town were "Cedar Hill Farm," built ca. 1852 by Yancy Wiley in the northwest quadrant of Lafayette County (Fig. 44), and the Shipp plantation house, located south of Oxford near the southern border of the county (Plate 5 and Fig. 45). Though no documentation exists, both could easily have been designed by Turner. In 1833, Dr. Felix Grundy Shipp had moved from Hinds County in central Mississippi north into the Chickasaw Cession

Figure 44

Cedar Hill Farm, Lafayette County, Mississippi (ca. 1852).

near the future town of Water Valley In 1839, he bought his Lafayette County land at the Pontotoc land auction and built his first residence—an inn on the stagecoach road. But Shipp was ambitious, and in the late 1850s, began to build his large, imposing mansion. [16]

According to historian Charles B. Cramer, Shipp, with the help of his numerous slaves, built his ten-room house facing the stage road, opposite his first residence: "Bricks used in the construction were made in two brick kilns on the place. The cypress shingles used on the roof of the house were dipped in boiling linseed oil to protect them from the harshness of the weather." The shingles lasted seventy-five years before a tin roof was placed over them. The timber frame was joined with sturdy wooden pegs. [17]

Two large rooms lay on either side of the broad central downstairs hall, which ran the depth of the house from the front portico to a porch at the back. An elegantly curved stairway, with carvings by black slave craftsmen, led to the second floor, which

Figure 45

Shipp House, Lafayette County, Mississippi (ca. 1857).

contained one huge room above the two first-floor parlors, the former of which was specially designed for meetings of the Masonic Lodge and the Methodist Quarterly Conference. Another upstairs space, called the Medicine Room, resembled a drugstore, with its shelves and cabinets filled with jars and bottles of medicine that Dr. Shipp dispensed to his patients. Plaster walls throughout the house were composed of sand, molasses, horsehair, and other ingredients. A stunning plaster medallion in the front parlor was a replica of one in Andrew Jackson's home, The Hermitage, near Nashville.

The family maintained the property until the death of Dr. Shipp's daughter Martha in the 1920s, after which the house was boarded up and abandoned. The family heirlooms left behind fell prey to vandals and antique hunters as the house slowly decayed. The abandoned stage road that once ran past it became choked with undergrowth and no longer passable, leaving the house isolated deep in the woods. It was a romantic ruin by the time Faulkner would likely have known it, in the 1920S, and possibly found it a suggestive model for the "Old Frenchman Place." Faulkner may or may not have known that the family had originally come from Shipp's Bend, Tennessee. When in 1936 he drew the famous map of his imagined Yoknapatawpha for the flyleaf of Absalom, Absalom !, he placed the hamlet of "Frenchman's Bend" and the nearby mansion, the "Old Frenchman Place," in the southeast quadrant of the county, the actual location of the "Old Shipp Place," as it was already coming to be knowm (Fig. 8).

An important literary model for Faulkner in the use of architecture as setting and symbol was the older Mississippi writer Stark Young (1881-1963), born in Como in Panola County and raised both there and in Lafayette County after his father, a physician, moved to Oxford in 1895. Young was a student and later a professor of drama and literature at the University of Mississippi before completing a distinguished academic career at the University of Texas and Amherst College. Although his fiction has been dismissed by later critics as belonging to the "moonlight and magnolias" school, Young established a lasting reputation as a preeminent drama critic, writing masterful columns for the New Republic and the New York Times . He had known young William Faulkner through various Oxford connections, particularly their mutual friend Phil Stone. Young helped Faulkner, despite the latter's weak academic credentials, to gain admission to Ole Miss as a special student. He also made it possible for the aspiring young poet to venture north to New York by allowing him to stay for a time in his own apartment and by finding him work in the bookstore of his friend Elizabeth Prall.

Figure 46

Tait House, Panola County, Mississippi (1848, demolished).

Faulkner clearly knew Young's Mississippi novels, the characters and settings of which were closely based on references from Panola and Lafayette counties. [18]

The title of Young's first novel, Heaven Trees (1926), derived from the name of the plantation house that served as its central venue. "I took the old Tait House for my setting," he recalled of the mansion around which the town of Como would later develop. It was "a fine place that had seven halls and on three sides porches in the Palladian manner with columns" (Fig. 46). Its builder, Young's uncle, Dr. George Tait, "had a diploma from some university to practice medicine, but his plantations had made that unnecessary, and the number of kin and family connections, from whom no fee could be collected, made it futile so that he soon forgot his saddle bags and devoted himself to books and whiskey. The place was haunted with the ghosts of happy elegance and drunken sprees and sorrow, pranks after the school of the frontier, gardens, celebrations, and the whole sarcasm of past time." [19]

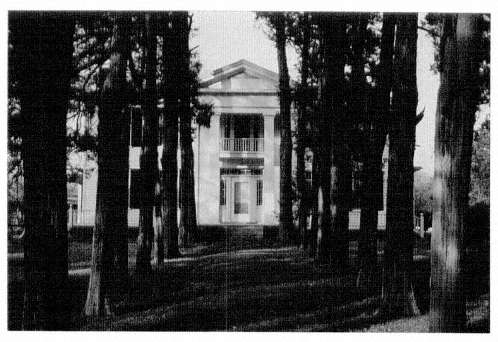

Young's second novel, The Torches Flare (1928), was set in twentieth-century" Clearwater," a north Mississippi town closely modeled upon Oxford. There, the house called "Friendship," the home of Dr. Dandridge, one of the book's central characters, strongly resembled several Lafayette County houses of the type designed by William Turner. It was in relatively good condition, compared to its once proud, now decaying contemporary, "The Cedars," which Young described as "a square house, gray and weathered." Around it "there were a few cedar trees, but no lot, no garden, and no wall or fence; only a gateway with posts remained" (Fig. 44). [20]

Similar evocations of Southern mansions, in both pristine and declining condition, appeared in Young's later novels, River House (1929) and So Red the Rose (1934), the latter of which was partially composed while Young was a guest at Cedar Hill Farm, northwest of Oxford on the College Hill Road. Though Young moved much of the action of his last novel from north Mississippi to the Natchez region in southwest Mississippi, attributes of houses from Lafayette and Panola counties permeate it. For example, he used a famous anecdote from Oxford oral tradition in which, during the Civil War, Union soldiers shot and killed a small Negro boy, while the child was hiding in the limbs of a tree on the lawn of the Neilson House. Faulkner knew Young's novels but left no record of his impressions. Though the older writer significantly anticipated him in his use of architecture as a central and defining element, the genius of Faulkner's achievement surpassed in every way the work of Stark Young, including his use of architecture as metaphor.

As one of the settings for Temple Drake's dark adventures in Sanctuary , where she is raped with a corncob by the impotent hoodlum Popeye, Faulkner used the Old Frenchman Place to symbolize social, cultural, moral, and spiritual decay: The house was a gutted ruin rising gaunt and stark out of a grove of unpruned cedar trees. It was a landmark, known as the Old Frenchman place, built before the Civil War; a plantation house set in the middle of a tract of land; of cotton fields and gardens and lawns long since gone back to jungle, which the people of the neighborhood had been pulling down piecemeal for firewood for fifty years or digging with secret and sporadic optimism for the gold which the builder was reputed to have buried somewhere about the place when Grant came through the county on his Vicksburg campaign. . . . The gaunt ruin of the house rose against the sky, above the massed and matted cedars, lightless, desolate, and profound. The road was an eroded scar too deep to be a road and too straight to be a ditch, gutted by winter freshlets and choked with fern and rotted leaves and branches (Plate 5 and Fig. 45). [ 21]

In The Hamlet , near the turn of the century, Faulkner presented the same abandoned house as being no longer owned or occupied by the descendants of Louis Grenier, the "old Frenchman," but by the backwoods entrepreneur Will Varner, who owned most of the good land in the country and held mortgages on most of the rest. He owned the store and the cotton gin and the combined grist mill and blacksmith shop in the village of Frenchman's Bend and at least once every month during the spring and summer and early fall . . . he would be seen by someone sitting in a home-made chair on the jungle-choked lawn of the Old Frenchman's

homesite . . . chewing his tobacco or smoking his cob pipe, with a brusque word for passers cheerful enough but inviting no company, against his background of fallen baronial splendor . He rationalized this habit only to V.K. Ratliff, the itinerant sewing machine salesman: I like to sit here. I'm trying to find out what it must have flit like to be the fool that would need all this . . . just to eat and sleep in. . . . But after all, I reckon I'll just keep what there is left of it, just to remind me of my one mistake. This is the only thing I ever bought in my lift that I couldn't sell to nobody .[22]

Will Varner's attitude to the Old Frenchman's Place, which he owned but did not live in, was one of bemused alienation from the original owners' values and intentions. By contrast, the view of another outsider to another grand house that he not only did not inhabit but had never seen the likes of, was vividly presented in the story "Barn Burning." There, through the mind of the abused and terrorized child, Sarty Snopes, Faulkner suggested the power of architecture to astonish, ameliorate, comfort, and delight (Fig. 40): Presently he could see the grove of oaks and cedars and the other flowering trees and shrubs where the house would be, though not the house yet. They walked beside a fence massed with honeysuckle and Cherokee roses and came to a gate swinging open between two brick pillars, and now, beyond a sweep of drive, he saw the house for the first time and at that instant he forgot his father and the terror and despair both, and even when he remembered his father again . . . the terror and despair did not return. Because, for all the twelve movings, they had sojourned until now in a poor country, a land of small farms and fields and houses, and he had never seen a house like this before . Hit's big as a courthouse he thought quietly, with a surge of peace and joy whose reason he could not have thought into words, being too young for that .[23]

Smaller, one-storey variants of the same Greek Revival graced Lafayette County in both Oxford and the countryside. Near the hamlet of College Hill, the Buford-Heddleston House (1842; Fig. 47) was characterized by crossing central hallways that opened on two sides onto identical four-columned porticoes, a partial, modestly rural version of Andrea Palladio's grand Villa Rotonda, Vicenza, Italy (ca. 1550). A smaller, but similar house in town, "The Magnolias," was built the same year by an early settler, William Smither (Fig. 48). Such houses, Faulkner wrote in Knight's Gambit , were more spartan even than comfortable even in those days when people wanted, needed comfort in their homes for the reason that they spent some of their time there .[24]

The house that so moved Sarty Snopes in "Barn Burning" was the ancestral seat of the de Spain family, but it could as easily have been the nearby country house "Sartoris," which Faulkner placed in the northwest quadrant of his Yoknapatawpha map, near the actual location of Cedar Hill Farm. It was significant that the Sartoris house

Figure 47

Buford-Heddleston House, College Hill, Mississippi (ca. 1842).

Figure 48

The Magnolias, Oxford, Mississippi (ca. 1842).

had no made-up name like "Longwood" or "Bellevue" but only the name of the family itself, a name Faulkner saw as having both dark and grand connotations: For there is death in the sound of it and a glamorous fatality, like silver pennons downrushing at sunset or a dying fall of horns along the road to Rouncevaux .[25]

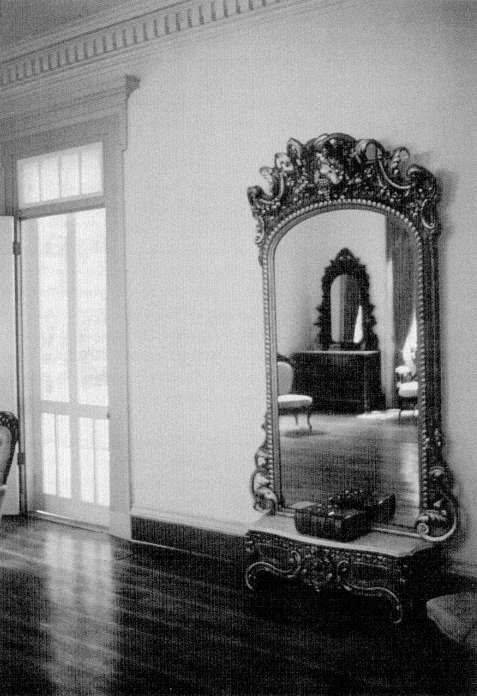

In the 1920s, Bayard Sartoris returned to and pondered the meaning of his ancestral home, burned by Federal troops during the Civil War and rebuilt over the original cellar and foundations afterward. Faulkner used such architectural layering to evoke the even more complex layering of the Sartoris family and indeed of Southern history. Though in most of his later work he would emphasize the exteriors of buildings as sculptural monuments on the natural landscape, in Sartoris he developed a sense of the layering of interior spaces as well (Fig. 49). It was remarkable that here in the first of his Yoknapatawpha novels, he had already developed a sophisticated sense of architectural symbolism: Then the road approached the railroad and crossed it and at last the house John Sartoris had built stood among locusts and oaks and Simon [the driver] swung between iron gates and into a curving drive. . . . Bayard stood for awhile before his house. The white simplicity of it dreamed unbroken among ancient sunshot trees . He then crossed the colonnaded veranda and entered the front hall. The stairway with its white spindles and red carpet mounted in a tall slender curve into upper gloom. From the center of the ceiling hung a chandelier of crystal prisms and shades, fitted originally for candles but since wired for electricity. To the right of the entrance, beside folding doors rolled back upon a dim room emanating an atmosphere of solemn and seldom violated stateliness and known as the parlor, stood a tall mirror filled with grave obscurity like a still pool of evening water .

Bayard then climbed the stairs and stopped again in the upper hall. The western windows were dosed with lattice blinds, through which sunlight seeped m yellow dissolving bars that but served to increase the gloom. At the opposite end a tall door opened upon a shallow grilled balcony which offered the valley and the cradling semicircle of the eastern hills in panorama. On either side of this door was a narrow window set with leaded panes of vari-colored glass which John Sartoris's younger sister had brought from Carolina in a straw-filled hamper in '69 .[26]

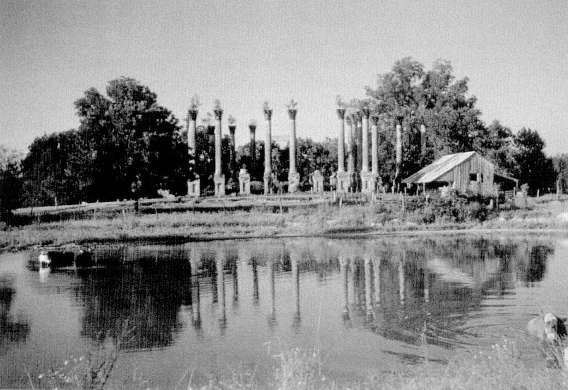

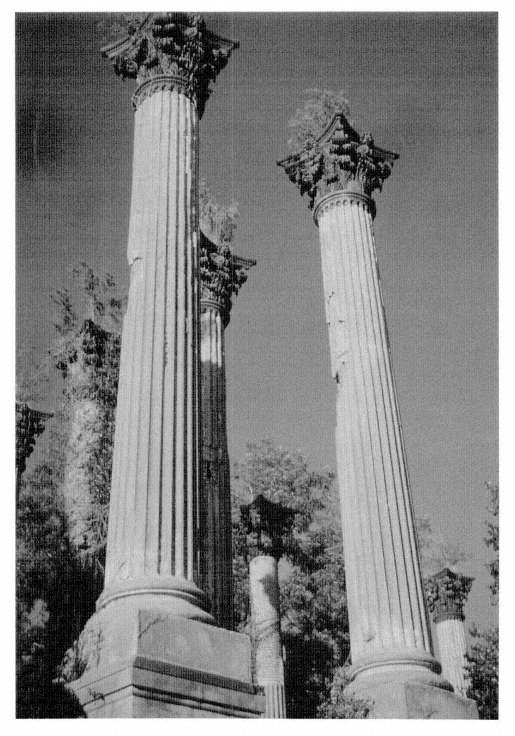

The building, the decay, and sometimes the destruction of such houses were crucial to the plots, the ambience, and the delineation of character in Faulkner's work: from the Old Frenchman Place in Sanctuary and The Hamlet to similar homes in town of the Compson and de Spain families, to the plantation house, Sutpen's Hundred, in Absalom, Absalom ! Though such apocryphal grandiosity had no real equivalent on the actual Mississippi landscape, except perhaps at the Tait House in Panola County (1848; Fig. 46), "Waverly" in Clay County (1850; Fig. 49), or houses in the Natchez district, such as

Figure 49

Reflected Interiors, Waverly, Clay County, Mississippi,

attributed to Charles Pond, architect (ca. 1850).

"Windsor" in Claiborne County (1860; Figs. 50 and 51), Absalom, Absalom ! would have lost much of its power without the prominence and the grandeur Faulkner gave to Sutpen's house, the other Grand Design, the private, monomaniacal counterpart of the public Grand Design of courthouse, square, and town. It was the symbol for Thomas Sutpen of the security he craved and worked for, a status denied him earlier at another grand house when he had been asked by a haughty servant to go around to the back door. In the middle of what the elder Jason Compson called a shadowy miasmic region something like the bitter purlieus of Styx , Sutpen decreed his own house into being as a kind of commandment: Be Sutpen's Hundred, like the oldentime "Be Light ." In Requiem for a Nun , Faulkner represented the mansion as being something like a wing of Versailles glimpsed in a Lilliput's gothic nightmare .[27]

The contrast between the names of the houses on the Sutpen and Sartoris plantations has been noted insightfully by critic William Ruzicka: "Sartoris itself is named, of course, for the family, and the name, in its own way, is an attribute or quality. Sutpen's Hundred is named for the number of square miles it contains—a quantity. The complete name is composed of two words: the possessive form of the owner's name and the quantitative measurement of what is possessed." [ 28]

The size of the house was, in fact, so colossal that the curious Jefferson gentry, eager to observe the phenomenon, would make up parties to meet at the Holston House and go out horseback, often carrying lunch. . . . Without dismounting (usually Sutpen did not even greet them with as much as a nod, apparently as unaware of their presence as f they had been idle shades) they would sit in a curious quiet dump as though for mutual protection and watch his mansion rise, carried plank by plank and brick by brick out of the swamp where the day and timber waited—the bearded white man and the twenty black ones and all stark naked . Like his slaves, Sutpen worked in the nude, they surmised, because he was saving his clothes, since decorum even f not elegance of appearance would be the only weapon (or rather, ladder) with which he could conduct the last assault upon . . . respectability .[29]

Sutpen and his crew of naked slaves worked from sunup to sundown . . . and the architect in his formal coat and his Paris hat and his expression of grim and embittered amazement lurked about the environs of the scene with his air something between a casual and disinterested spectator and a condemned and conscientious ghost—amazement, General Compson said, not at the others and what they were doing so much as at himself, at the inexplicable and incredible fact of his own presence. But he was a good architect . . . And not only an architect, as General Compson said, but an artist since only an artist could have borne those two years in order to build a house which he doubtless not only expected but firmly intended never to see again. Not, General Comp-son said, the hardship to sense and the outrage to sensibility of the two years' sojourn, but Sutpen :

Figure 50

Windsor, Claiborne County, Mississippi (1860, burned 1890).

Figure 51

Windsor, detail.

Figure 52

Estes House, Panola County, Mississippi (ca. 1855, demolished).

that only an artist could have borne Sutpen's ruthlessness and hurry and still manage to curb the dream of grim and castlelike magnificence at which Sutpen obviously aimed, since the place as Sutpen planned it would have been almost as large as Jefferson itself was at the time .[30]

Then, when it became altogether too claustrophobic, too threatening, the "French architect"—as much in thrall to Sutpen as were the African slaves he supervised—attempted to escape from it all through the swamp back to the river and south to New Orleans. And in relating this surreal episode, the great Faulkner wit emerges in a novel that is not usually thought to contain much humor, as he turned the word "architect" from a noun into a verb: It was late afternoon before they caught him . . . and then only because he had hurt his leg trying to architect himself across the river .[31]

When the work was completed, Sutpen's presence alone compelled that house to accept and retain human lift; as though houses actually possess a sentience, a personality and character acquired, not so much flora the people who breathe or have breathed in them inherent in the wood and brick or begotten upon the wood and brick by the man or men who conceived and built them but rather in this house an incontrovertible affirmation for emptiness, desertion; an insurmountable resistance to occupancy save when sanctioned and protected by the ruthless and the strong .[32]

Figure 53

Estes House, stairhall.

After surviving the war but not the collisions of Sutpen and his heirs, Sutpen's Hundred, before its ultimate destruction by fire, suffered a decline more ruinous and symbolic even than that of the Old Frenchman Place: Rotting portico and scaling walls, it stood . . . not invaded, marked by no bullet nor soldier's iron heel, but rather as though reserved for something more: some desolation more profound than ruin . . . that barren hall with its naked stair . . . rising into the dim upper hallway, where an echo spoke which was not mine, but rather that of the lost, irrevocable might-have-been which haunts all houses (Figs. 52 and 53). [33]

The fall of the House of Sutpen was a nineteenth-century Mississippi version of the fall of the House of Atreus in the Greek dramas of Aeschylus in the fifth century B.C . Indeed, the Greek Revival architecture of Yoknapatawpha was the perfect setting for Faulkner's Greek tragedies.