Chapter I—

Style and Topography

1—

Corrozet, Serlio, Androuet du Cerceau and de l'Orme

In 1550 Gilles Corrozet in his Antiquitez et Singularitez de Paris, ville capitale du Royaume de France wrote: 'There are a large number of houses [in Paris] which have declined as the times have changed and are now in the hands of others: for once there was not a Prince, Lord nor Prelat in France including the twelve Peers of the Realm who did not have a town house, because it was here as a rule that the King held Court. There are in our day some remarkable buildings in the Romanesque, Greek and Modern styles and I shall let you have the names of these for there are too many important houses to count: and every day the building of new houses goes on, which makes me believe that the City of Paris will never be completed.'[1] Around 1608 Malherbe in a letter to Peiresc wrote: 'If you come back to Paris in two years' time you will not recognize it.' Natives and foreigners wrote much in praise of the city during the sixteenth century but never go into any detail on the style and function of the buildings which in their eyes were contributing so much to the prestige and embellishment of the city. The earliest and most intriguing description of the style and function of an ideal gentleman's house came from Corrozet in 1539; a house which faced east to enjoy the sunrise, built of at least two types of good quality dressed stone including marble, with an imposing door either as an entrance gateway or on the body of the house itself, and numerous other features of note such as a forecourt paved in marble and a garden court.[2] The physiognomy of the house described by Corrozet might be imagined in a number of ways by the reader, but his house may well correspond to an early 'classic' Parisian town house on a rectangular site with the main block set between forecourt and garden and hidden from the street by an entrance screen. Corrozet does not describe the architecture of the elevations of his 'Invention Joyeuse', whether it is Gothic or Classical, Romanesque, Greek or Modern, but in one line he describes it as a 'Maison de pris, bien paincte à l'antiquaille', and later when he talks of the beauties of the garden front he lists medallions and statues both ancient and modern. The irony of Corrozet's long description is that it contains little or nothing for the architectural historian interested in plans and elevations, but it is a rare view in detail of a prestigious house through the eyes of a sixteenth-century Parisian. Apart from the quality of the materials and noting the

developed artistic tastes of the owner, Corrozet was more at pains to describe the fittings of each room from the master bedroom to the kitchen. The first published guide to the City of Paris and its monuments was Corrozet's Fleur des Antiquitez . . . de Paris of 1539 which gives the reader an agreeable historical and topographical account of the various 'quartiers' and some of their buildings, in which Corrozet shows no more interest or awareness of the changes from the Gothic to the 'classic' and classical in the town houses of his times. Contemporary printed texts are of limited value in the history of the Parisian hôtel , and so another class of book needs to be exploited, the architectural pattern books of Sebastiano Serlio (1475–1553) and of Jacques Androuet du Cerceau (c . 1510–1585) and the architectural treatises of Philibert de l'Orme (1505/1510–1570).

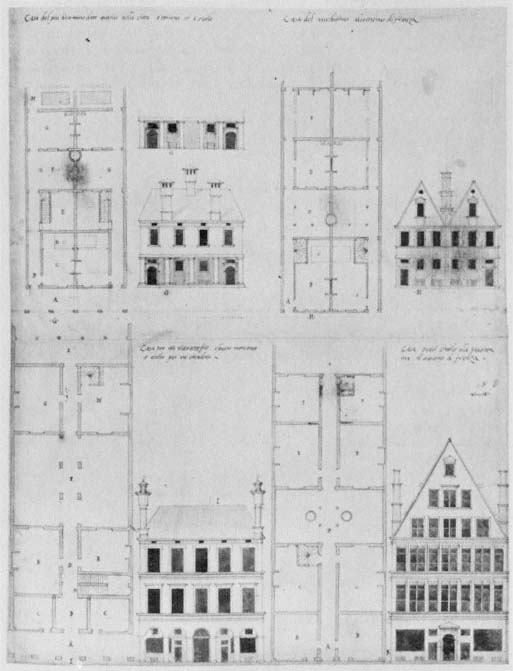

Serlio's life, career and 'literary remains' have been amply described elsewhere and there is more to come,[3] but for our purposes it is the last decade of his life spent in France preparing his pattern book On Domestic Architecture which is our first graphic and systematic evidence of the forms and styles of town houses interpreted by an Italian 'in modo di Francia' (Figs 1–5). Serlio's drawings of the plans and elevations of town houses in the Italian and French idioms are rightly said to be ideal rather than actual schemes, but his houses in the French idiom are based on unidentified and lost houses which he had studied at Paris and Fontainebleau from 1541 to 1546. The perfect regularity of the sites seen in Serlio's plans precludes any possibility that they are records of houses seen by Serlio, for regular sites were almost unknown in the built up areas within the city walls, and his drawings predate the development of the large lotissements of the later 1540s and 1550s which will be described below. The town houses drawn by Serlio range from houses for the poor artisan on to or up to houses for rich merchants, but Serlio cannot have been focusing on Paris when he wrote that the dwellings of the poorest men are located in the suburbs close to the city near the gates and therefore near to the markets and fairs. In the Paris of the early sixteenth century, with the exception of the streets nearest to the Louvre, the affluent and rich were distinguished only by the number of plots and of houses which they had acquired in comparison to their poorer neighbours. Serlio's syntheses of the artisans' and the merchants' houses summarize and rationalize some planning and building traditions known to have existed in Paris before he came to France, but the greater part of his book On Domestic Architecture deals with town and country houses for noble gentlemen, Princes and Kings. It is in these drawings of noble and princely houses that we find ideas and ideals of plan and of elevation which set revised standards for Parisian master masons and architects and created new ambitions and fashions amongst patrons. The remarkable feature of this class of designs by Serlio is how well they anticipated the new architectural opportunities of the lotissements of the mid and late 1540s.

Serlio never categorized or fully described his thoughts on the problems of building in towns, especially French towns, but scattered through his

2

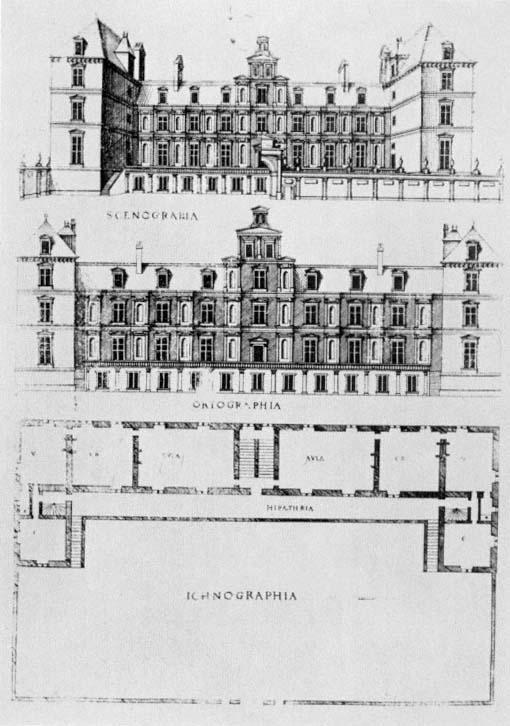

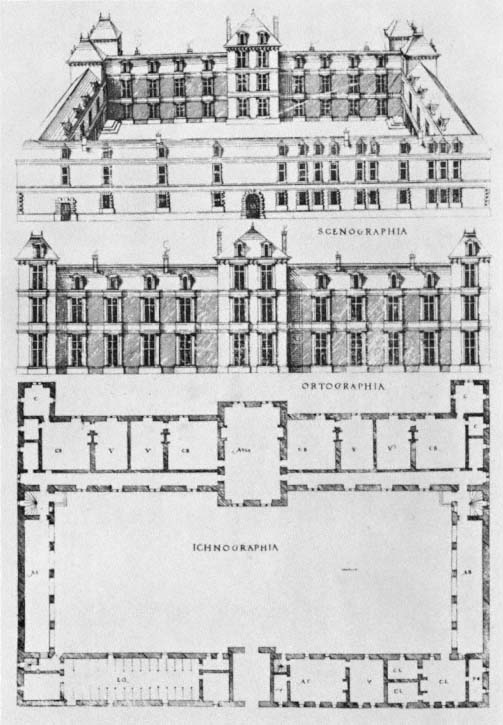

Sebastiano Serlio: Houses for bourgeois in the Italian and French manner. (Avery ms. n° XLIX)

3

Sebastiano Serlio: Houses for wealthy bourgeois in the Italian and French manner. (Avery ms. n° L)

4

Sebastiano Serlio: Houses for rich bourgeois in the Italian and French manner. (Avery ms. n° LI)

5

Sebastiano Serlio: House for a rich citizen or merchant in the French manner. (Avery ms. n° IV)

writings is a series of remarks which when collected give a fascinating insight into the relationship of patron, architect and builder, and of building tradition and styles at Fontainebleau and Paris. He insisted that the architect's first duty was to please his patron, and ' . . . la casa e fatta prima per la commoditta: piu per che pei Decoro . . .' Serlio had a keen sense of stylistic decorum which decisively influenced French writers on architecture up to the eighteenth century and which can be seen in some Parisian hôtels begun before his death. His thoughts on the decoration of the elevations of a building were both hierarchical and empirical; the most elaborate ornament (and by implication the most pretentious) on town houses should be reserved for the very great of the land, with the houses of those of lesser social rank, however wealthy, bearing fewer if any classical and armorial adornments. The empirical side of Serlio's thought is found in his acceptance and appreciation of window spacings which catered to the needs of the rooms inside, before a 'concordant disharmony'[4] , before any requirement for regularity or exact symmetry of both halves of an elevation, and which he noted as a likeable quality in French building, ' . . . where people like licentious things more than regular things.' Tall dormers were a happy French invention in Serlio's eyes, in the way in which they crowned a building, and as we know from other kinds of writing from the period, a building's imposing silhouette contributed to its romantic appeal. The decorative systems on the buildings in Serlio's drawings were no more than proposals in his mind, and were not intended as samples of model applied architecture in a dogmatic neo-classical sense. The design and proportions of decorative details and the size and use of rooms were decisions which would finally lie with the patron whom, he knew from his own experience, was likely to have opinions on such matters.

The number of drawings in the two manuscripts of Serlio's book which can be reliably associated with private houses at Fontainebleau and Paris is small. In the text which accompanies the sixth drawing in the Avery Library manuscript, Serlio summarizes the character of the houses built in and around Fontainebleau during the reign of François I as ' . . . case continuare in longezza . . .' (Fig. 5). Here the site is broad and rectangular with the main block or corps de logis built across the middle. The elevation is simple but not austere with a tall 'piano nobile' over the basement offices and stores. The pitch of the roof starts from a cornice, and the dormers are given alternating triangular and curved pediments. A double ramp central staircase leads into the vestibule from the courtyard and garden sides, and access to the attic floor is by the two spiral staircases in the small angle pavilions in the left- and right-hand corners of the courtyard. In a much quoted phrase, Serlio wrote that an outstanding quality he found in French houses was their comfort, which might be interpreted as their practicality, and we can follow in this plan the arrangements for the service functions, and the partition of the public from the private life of a Bellifontaine or Parisian house to which Serlio alludes. Corrozet spoke of the pleasure of

the sunrise, and this typical hôtel from Serlio shows a well-lit corps de logis only one room deep, an enfilade which had become standard by his day and was to remain in favour up to the late seventeenth century. Compared with Paris during the first three decades of the sixteenth century, building at Fontainebleau during the 1540s took place in more favourable conditions on large green field sites around the château and we shall see how these standards created higher expectations for building in the capital.

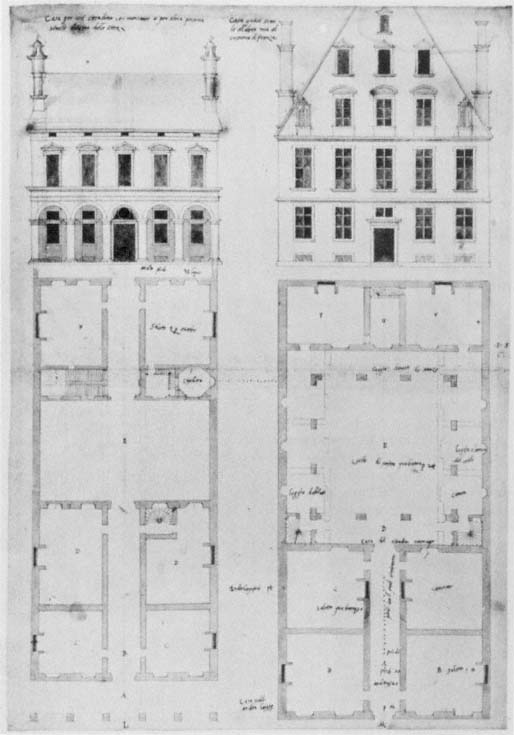

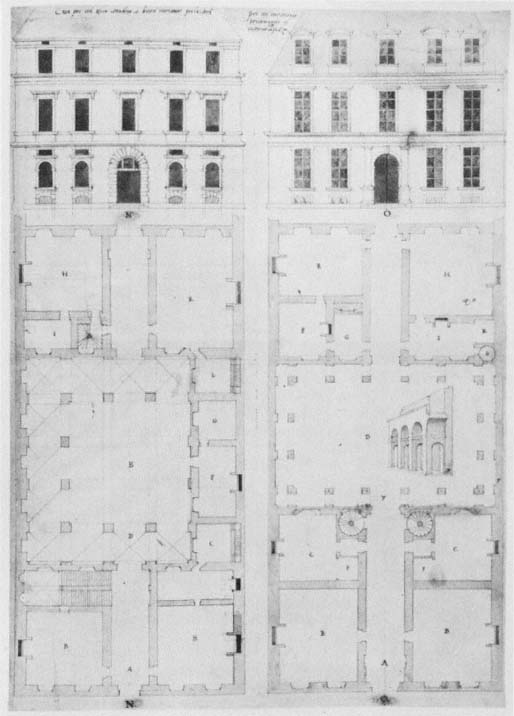

The most prolific popularizer of architectural design of Renaissance France, Jacques Androuet du Cerceau the Elder, owned or borrowed the Avery Library manuscript of Serlio's book. Du Cerceau plagiarized a great deal from Serlio, and his first Livre d'Architecture published in Paris in 1559 owes its format but few of its fifty designs to the Italian. The schemes in du Cerceau's book are all in a distinctively French manner but the book is most remarkable for the variety and fancy of its plans of the large scale buildings with square, rectangular, circular, cruciform and octagonal courtyards. The large ideal schemes may well have impressed Parisian builders and patrons with the systems of the elevations, but it is amongst the smaller projects at the beginning of du Cerceau's suite that we should look for plans which might have been conceived with Paris in mind, or more probably were based on recent Parisian buildings. The first and smallest of du Cerceau's series (Figs 8–9) for a person of 'moyen estat' is a design for a corps de logis , without any subordinate buildings or topographical context, but this is the sort of structure to be expected on a rectangular city site, on a thoroughfare.

The plans of the basement, ground and first floors of this house provide an interesting social insight, with unlit cellars below ground, a ground floor where the whole of the left half is taken up with the kitchen which is evidence of a traditional bourgeois social priority, and the first flight of the main staircase leading to a first floor with from left to right a chambre (Cubiculum), garderobe (Vestiarium), or wardrobe and a salle (Aula) or hall, which would have been the living room cum dining room. The chambre with its wardrobe would have been the owner's apartment with the hall across the landing as the only reception room of the house. The use of the attic floor is not specified by du Cerceau, but it would be used conventionally for children or servants. This scheme is a perfect example of French 'comfort' as understood and interpreted by Serlio. The windows are arranged so as to give each room light in its middle, rather than any effort being made at strict uniform balance in the elevations. The street front has raised lights to keep out the gaze of the curious passerby from the kitchen and the other room on the right of the ground floor, which would have been a convenient place of business for the bourgeois. The small raised cabinets on the back of the house were to become a popular feature for courtyard and garden fronts well into the reign of Louis XIV, and inside they were rarely much larger than the five feet square in du Cerceau's design. Such tiny rooms were to be found in both town and

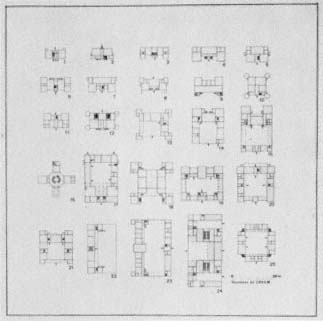

6

Scale plans of projects 1 to 25 of Androuet du

Cerceau's Livre d'Architecture of 1559.

Drawing by Monsieur Jean Blécon of CRHAM, Paris.

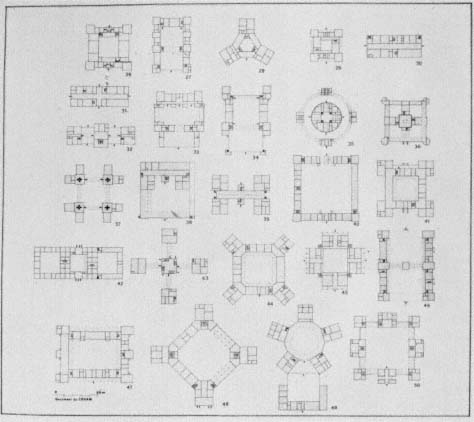

7

Scale plans of projects 26 to 50 of Androuet du Cerceau's Livre d'Architecture of 1559.

Drawing by Monsieur Jean Blécon of CRHAM, Paris.

8

Androuet du Cerceau: Plan of Project I from the Livre d'Architecture of 1559.

Cellars at the bottom, ground floor in the middle and first-floor plan at the top of the engraving.

9

Androuet du Cerceau:

Street and courtyard elevations of Project I from the Livre d'Architecture of 1559.

country houses as the inner sanctum of the owner for work, study, prayer or as a strong room for his valuables.

Du Cerceau's designs XIII, XIIII and XXI show the most common form of house in the Livre d'Architecture (Figs 10–13) where he explores the possibilities and varieties of square and rectangular sites. Whether he thought of them as town or country houses is irrelevant, for with minor alterations such as the removal of the angle pavilions on XIII, their size and concentration of living and service parts made them suitable propositions for either a château or an hôtel . The corps de logis of XIII is of five regular bays and two floors of equal height on the courtyard, with one bay blocked out at the back. This adjustment was made at the back because of the different widths of the lateral wings of the courtyard. The corps de logis is an enfilade one room deep entered on both floors from a ramp staircase in the right-hand corner of the court, which divides the hall and apartments from the kitchen, servants' rooms and the latrines. The truly prestigious features of this house are the battlemented entrance screen with its rusticated arch and statues, and on the left of the courtyard the arcaded gallery at the end of which was the seclusion of a small chapel or oratory. The arcade of the gallery would have been used for stores, horses and carriages, and as shelter from the rain for the attendants of a visiting dignitary. This house has a clearly organized circulation. The division between the owners and the servants is more pronounced in XIIII (Fig. 11) where two small open spaces or areas separate the corps de logis from the kitchen wing on the left and from the stable wing on the right. The windows in the corps de logis facing these small interior courts shows that they were open spaces, but the windows faced a screen to protect the ladies from a view of the kitchen staff and from the sight of the stable's lavatories. The divorce of the main block from the service buildings allows a perfectly symmetrical arrangement of rooms with access from left and right of the courtyard, rather than the one route offered in XIII. XIIII is a scheme for a substantial house, and was most suited to the city with its incorporation of the stables, which at a country house would be farther removed. We know from seventeenth-century opinion of the dislike of cooking smells amongst the nobility,[5] and from these plans the dislike was as pronounced in the sixteenth century with kitchens removed as far as possible from the main house.

The classical trappings of the elevations of houses of this scale in du Cerceau's book are limited to arcading for galleries, friezes and cornices to divide the floors, and pedimented dormers. Only on houses of a very grand aristocratic or Royal scale such as XXII (Fig. 14) do systems of columns or pilasters appear on a corps de logis . The preceding scheme (Fig. 13) which has much in common with XIII and XIIII has an austere architecture on the lateral wings and main block, to contrast with an entrance screen (Fig. 12) which is like a cryptoporticus without the requisite floor above. Its depth would have made it a public utility on a rainy day, instead of the more familiar form of entrance screen wall with its military

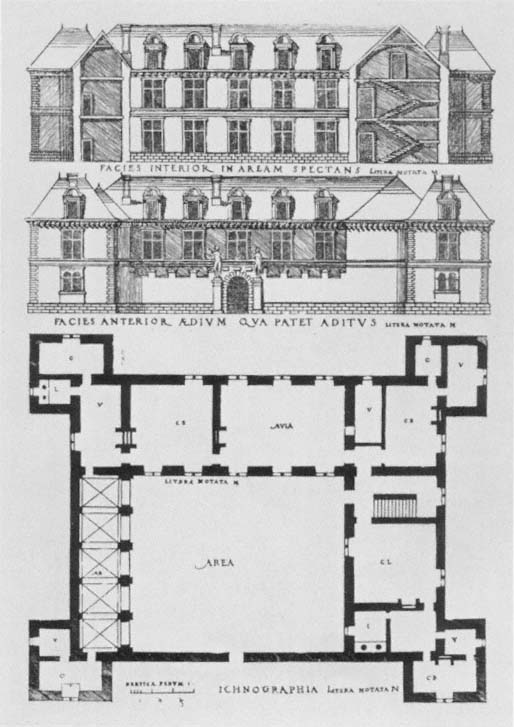

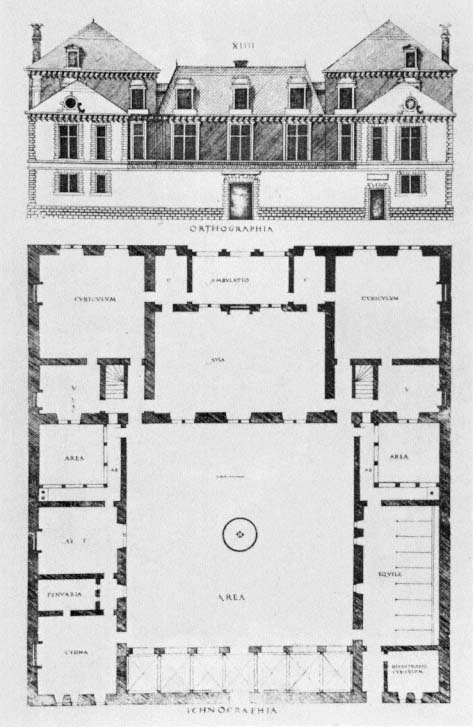

10

Androuet du Cerceau: Project XIII from the Livre d'Architecture of 1559.

11

Androuet du Cerceau: Project XIIII from the Livre d'Architecture of 1559.

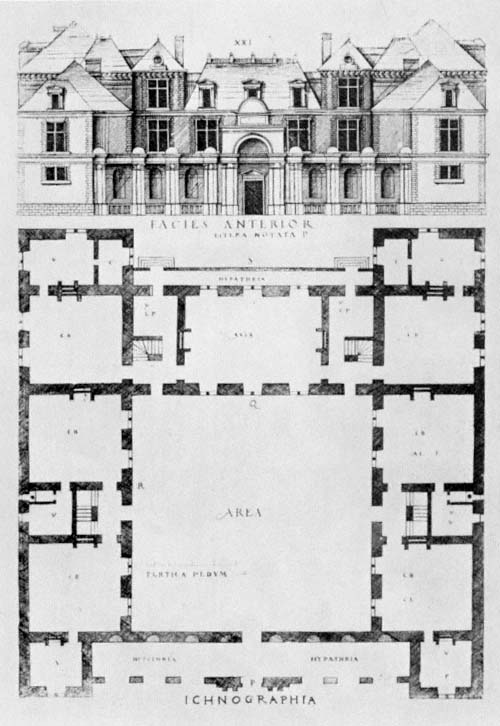

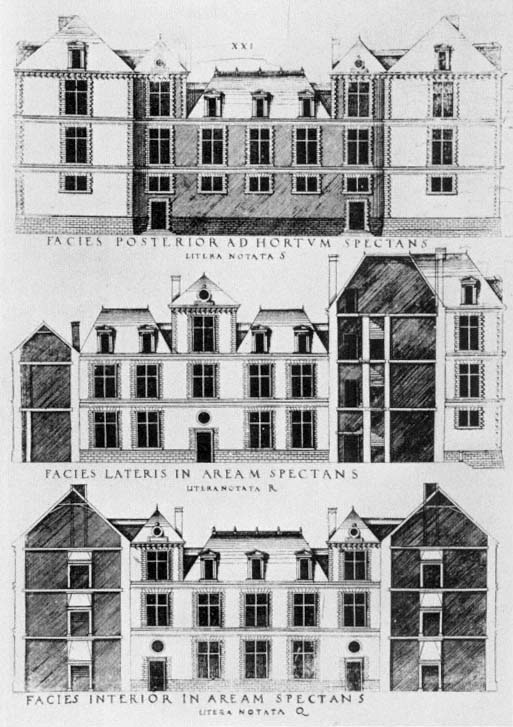

12

Androuet du Cerceau: Project XXI from the Livre d'Architecture of 1559.

13

Androuet du Cerceau: Back elevation, lateral and middle sections of Project XXI from the Livre d'Architecture of 1559 .

crenellation or rustication. As portrayed by du Cerceau, the square courtyarded house is shown as a flexible form of plan, suitable for a strictly hierarchical society, and in which the components could be treated in various contrasting manners.

If Androuet du Cerceau's plates in the 1559 Livre d'Architecture give us a fine repertoire of house planning and style from the 1550s, shorn of the Roman and Venetian style villas, castles and palaces which complete Serlio's offering of domestic design, the Frenchman provides not one word of stylistic theory or advice. His foreword to the notices describing each building is concerned only with describing the toise (1.959 metres), the statutory unit of measurement, and costing for building contracts in Paris with regional variations. The notices on each building of the Livre d'Architecture are dry and to the point, with the total number of toises required given at the end for the reader to calculate the cost at the current prices, the first and cheapest has a total of 539 toises , 16 pieds , XXIII and XXIIII have 2610 and 2750 toises respectively, and the fiftieth and largest scheme at the end of the book has 9110 toises . Reading du Cerceau's text and browsing through the plates the modern reader can see du Cerceau keeping elaborate detail to a minimum even in the larger projects. His sense of the practical led him to publish a Second Livre d'Architecture two years later in 1561, where he illustrates elaborate and costly designs for fireplaces, doorways and dormer windows, presumably for those who have avoided trouble with their masonry contract, and might wish to add some ornate detail.

By an edict of 1557, Henri II sought to standardize Parisian methods of costing a building.[6] The Parisian convention had been to price a wall on its length, height and depth, with any decorative elements such as an architrave counted as double the unit price, and without a reduction being made for voids such as doors and windows. The Royal edict required a new system in which the voids were accounted for and deducted, and applied decorative elements such as simple pilasters, friezes and cornices were included and specified in the price for the wall. The consequence of the new regulation was that a master mason was reluctant to agree to, or to observe the finer decorative points which might be given in an architect's drawing, and a separate agreement on the basis of an agreed and initialled drawing was recommended.

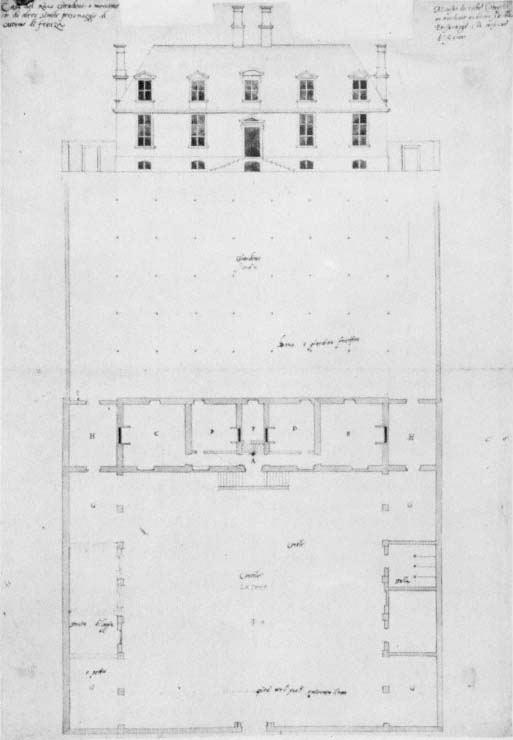

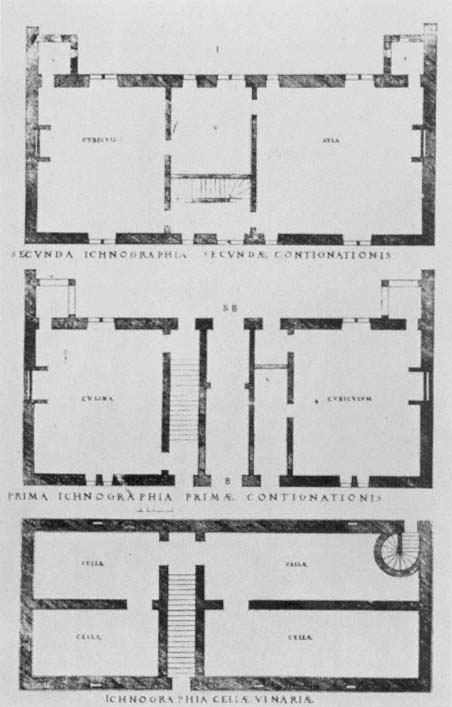

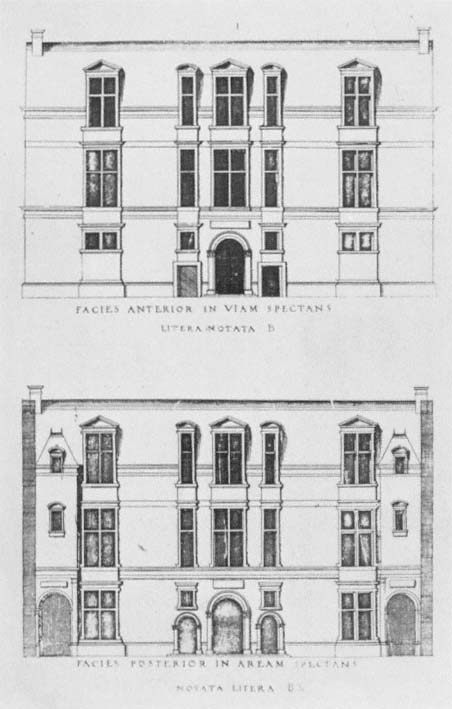

Philibert de l'Orme was the only author on architecture to speak with both theoretical and technical authority in his Premier Tome d'Architecture of 1567 and his Nouvelles Inventions pour bien bastir of 1561. In Paris he was the architect of the Tuileries palace for Catherine de Medici and of a small number of lost and unrecorded 'hôtels'.[7] In his books he had little to say which specifically concerns the topographical conditions of building in Paris, on the styles, types and configurations of town house building of his times. His thoughts on style and his expertise in building techniques and engineering are woven into an account of the châteaux designed by himself

14

Androuet du Cerceau: Project XXII from the Livre d'Architecture of 1559.

15

Androuet du Cerceau: Project XXIII from the Livre d'Architecture of 1559.

during the late 1540s and 1550s, and much of his description of building techniques is useful in an account and description of Parisian houses of the last quarter of the sixteenth century, in particular the complicated masonry of suspended cabinets and his carpentry ideas for economical pitched roofs. This egocentric and violent man only illustrated and described the house he had built for himself in the rue de la Cerisaie as a contribution to the upper middle-class town house which could be built without unnecessary expense (Figs 92–94). For this we can be grateful because here he addressed himself to the limitations and an appropriate architectural style for a house on a typical plot on one of the Royal lotissements at the Hôtel Saint-Pol near the Bastille. The plan of his house on a long-rectangular site is known, and with the three woodcuts of its elevations and with his text, de l'Orme has left both an architect's and an owner's prescription for a good town house of the 1550s, built well and without excessive cost. De l'Orme in the decade when he was building his Parisian hôtel accumulated honours from the Court and a sizeable but not excessive fortune. Despite his rise and prestige de l'Orme built a house which was about 13 metres in width, compared to the first and smallest town house in du Cerceau's Livre d'Architecture which spanned a site about 22 metres in width. The pattern books of Serlio and of Androuet du Cerceau provide abundant information on form and style which accompanies and complements the development of the Parisian town house, but du Cerceau made no attempt to record the hôtels of his native city, which is irritating in a man whose major life's work was a Royal commission to draw and engrave the great country houses of France, Les plus excellents Bastiments de France , two volumes of which were published in 1576 and 1579. De l'Orme's books have a wealth of advice on materials and building procedures which helps with an account of sites and building contracts.

2—

The Lotissements and Building Contracts

Two practical factors conditioned the evolution of the form and style of the sixteenth-century Parisian hôtel . The organization of the lotissements for building development of the 1540s determined the size and shape of new houses, and the terms and system of costing of the notarial Parisian building contract provide a basis for understanding the stylistic choices available and the decisions made by patrons and architects.

The costs of a new war against the Emperor Charles V is the principal reason given by François I in the edict of the 23 September 1543, for the division into lots and sale of the royal Hôtels de Bourgogne, d'Artois, de Flandre, d'Etampes and Saint-Pol, leaving only the Louvre in the west, and the rambling Hôtel des Tournelles in the east on the north side of the rue Saint Antoine.[8] The expenses of a campaign was the traditional motive for a monarch to sell land, titles and offices, but in this case an unusual

16

Plan of the lotissement of the Hôtel de Flandre in 1543, from Dumolin.

rider was included in the text of the edict, that these royal properties were ' . . . vieils, inutiles, inhabités et délaissées en ruyne ou décadance . . .' and do nothing more than ' . . . encombrer, empescher et defformer grandement la ville de Paris . . .', and these holdings as a result of the royal edict could become ' . . . fort propres, utiles, et avesnables a bastir et ediffier plusieurs beaux logis, maisons et demeures'. Not since the Hundred Years War had there been an initiative on the scale and importance of the lotissement of the Hôtel Saint-Pol, with its novel straight streets, and at 10 metres in width they were wide for Paris of the period. Medieval royal palaces in Paris, with the exception of the compact Louvre, covered large areas with numerous corps de logis , halls and service buildings, connected by

17

Plan of the lotissement of the Hôtel Saint-Pol from 1543 to 1556, from Mirot.

galleries and arbours and separated by irregular courtyards and gardens, as was the Hôtel Saint-Pol of Charles V and VI. Parts of these sprawling complexes had been given or leased to royal favourites up to the 1520s, and the resolve of the Crown to generate the maximum revenue from these lotissements is shown in the revocation of all gifts and termination of leases on small and large portions of the properties, so that these new quartiers could be methodically developed with grid pattern streets and regular building plots to attract those with means. As can be seen in the outline plans of the lotissements of the Hôtel de Flandre and the Hôtel Saint-Pol (Figs 16–17) the scale of the plots varies with the smaller lots usually lining those streets which were expected to be the busiest, for houses with shops or offices on the ground floor of a kind seen in du Cerceau's first project (Figs 8–9). The large plots for substantial houses were on the streets which were quieter without direct access between the main thoroughfares.

Encouraged by the example and initiative of the Crown, the prior of the Church of Sainte-Catherine, which stood north-west of the Hôtel Saint-Pol on the north side of the rue Saint-Antoine, resolved to sell for upper-class development the meadows and market gardens north of the church. Saint-

Catherine already drew part of its income from some houses which stood between the church and the rue Saint-Antoine, which from the fourteenth century had been leased for periods of ninety-nine years. By the 1540s the increased number of monks meant that income from existing leases and other sources of revenue was inadequate and they set about exploiting their major asset the Culture Sainte-Catherine. During the first three months of 1545 (new style) the legal formalities of the conditions of sale and lease were decided upon and completed, and the plan of the lotissement was drawn up by the prior, a notary and other unidentified professional men,[9] with a scale of prices for leases (Fig. 18). At the south-east a new area was opened at the west end of the church from which started the Grande rue Sainte-Catherine, one of two long streets running from south to north, the other being the shorter rue Payenne named after Payen the monks' notary, and from west to east across the middle of the area an extended rue des Francs Bourgeois. Of the fifty-nine circled numbered plots shown in the outline plan (Fig. 18), fifty-three were sold between March and June 1545, most of which were between 120 and 150 square toises . As the outline plan shows, the greater number of lots were bought up in multiples of two to five, and the list of the first buyers and later owners on the Culture Sainte-Catherine is full of the names of leading lords, courtiers, diplomats and administrators. Robert Dallington writing in or shortly after 1598, having described the Tuileries noted, 'There be other very many and stately buildings, as that of Mons. Sansuë, Mons. de Monpensier, de Nevers, and infinite others, whereof especially towardes the East (i.e. the Marais and especially the Culture Sainte-Catherine) and this towne is full, in so much as ye may say of the French Noblesse, as is elsewhere said of the Agrigentines, "They build as if they should live ever, and feede, as if they should die tomorrow". But among all these, there is none (sayth this Author) that exceed more than the Lawyers, "Les gens de Justice (et sur tout les Tresoriers) ont augmenté aux seigneurs l'ardeur de bastir": The Lawyers and especially the Officer's of the King's money, have enflamed in the Nobilitie the desire of building: . . .'[10]

On 18 March 1545 (new style), only eight days after two notaries had been instructed to 'dresser les baux à rente des terrains', Jacques des Ligneris, seigneur de Crosne and President of the Parlement de Paris exactly the kind of man referred to by Dallington, bought the five plots 27 to 31, a total of 600 toises . Des Ligneris built a house on this land which is of central importance in the history of French Renaissance architecture and sculpture, and which in company with documented or surviving houses from the reigns of Henri II, Charles IX and Henri III made the lotissement of the Culture Sainte-Catherine the greatest architectural event and opportunity of the period, and a remarkable commercial success for the monks.[11]

The stimulus for the upper classes to build in Paris during the middle and late sixteenth century has been attributed to decisions made by François I. The speed with which the leases on the Culture Sainte-Catherine were

18

Plan of the lotissement of the Culture Sainte-Catherine in 1545, from Dumolin.

snapped up proves the strength of the need and demand for building land within the walls of Charles V. Other royal edicts put further pressure on the available land between the two sets of medieval walls, the inner and earlier set of Philippe Auguste and the outer range from the reign of Charles V. Henri II's ordonnance of 23 November 1548 forbade any new building in the faubourgs just outside the walls on both banks, and the act was to be enforced by demolition at the owner's expense with other penalties. The ordonnance was renewed on a number of occasions during the later sixteenth and seventeenth centuries because of the problems of policing and servicing an uncontrolled expansion of the city. The royal and municipal jurisdiction might have been extended to areas beyond the walls, but this was not considered to be in the interests of the city's privileges, economy or security.

After the death in 1559 of Henri II from wounds after a jousting accident at the Hôtel des Tournelles, his superstitious widow Catherine de Medici decided to sell the rambling palace. The exact limits of the Tournelles are not easy to follow now, but it was a considerable area on the north side of the rue Saint-Antoine, opposite the Hôtel Saint-Pol, the neighbour of the Culture Sainte-Catherine to the west with the walls of Charles V on the east. Letters patent published on 23 January 1563 describe a programme for the development of the quarter which is the earliest record of a fully coherent royal initiative in town planning.[12] The document starts with the usual preamble on the city daily growing more populous and how the majority of newcomers and natives are obliged to build outside the walls of the city because of the shortage of building space. Philibert de l'Orme's brother Jean was to design a pattern of streets and open spaces; land was to be sold in regular plots on condition that the purchasers built their houses within two years. The novel clause in the text is the proviso on the houses being 'uniformes et semblables'. Jean de l'Orme was to design a comprehensive scheme with architecturally coherent street elevations, but unfortunately the letters patent do not specify whether the intention was to create an haut-bourgeois and aristocratic residential quarter or one which incorporated a mixture of commercial premises with housing for a wide social spectrum. Any drawings made by l'Orme for the transformation of the area have not survived and the project was never started, but something of the 1563 scheme may be echoed in the Place des Vosges built forty years later for Henri IV on part of the site of the derelict Hôtel des Tournelles, which determined the east of the Marais as haut bourgeois and aristocratic.

Estimates of the size of the population of Paris during the sixteenth century vary, and considerable fluctuations are to be expected with the horrors of the Wars of Religion in the second half of the century. Figures of 350,000 to 500,000 have been given for the late 1520s, with one million in 1577, which drops to 200,000 to 300,000 souls in 1596. The guesses of a Venetian ambassador or a modern historian of the city's population do

little to help with the history of the physical development and rate of building expansion of Paris. The periods of pressure of population led to taller tenement building in the older quarters on or near the main arteries, the rue Saint-Denis, the rue Saint-Martin on the Right Bank and the rue Saint-Jacques on the Left Bank. The story of the lotissements illustrates one aspect of the filling in of the area within the walls, but this process should not be related to pressures from a growing population, but to the ambitions of speculators, and of the wealthy for a more salubrious life in the town with gardens and other agreeable features. The first large addition to the limits of Paris on the Right Bank since the fourteenth century was the start made in 1566 on new fortifications for the west of the city, and which moved the Porte Saint-Honoré out by 950 metres.[13] Only with the completion of the fossés jaunes under Louis XIII, which ran from the west end of the Tuileries gardens round to the Porte Poissonière in the north, did a full and rational lotissement of the area take place. The improvement in the city's appearance foreseen by François I in 1543 was not a radical or grandiose proposal to embellish the capital of the kind which preoccupied architects under all of the Bourbon Kings and Napoleon, but it was a practical wish to see accommodated a larger resident professional aristocratic class in new and renewed portions of the Right Bank, and at a profit to the crown.

Once a gentleman or businessman had bought his land on one of the lotissements , he was usually obliged as a condition of the sale to build within a prescribed number of years, and one of the results of such stipulations was numerous cases of sale and resale before any building was started. The design of the house might be entrusted to an architect, but from the evidence of the great majority of surviving building contracts, an architect was consulted or employed on surprisingly few occasions in the second half of the century. Custom and architectural books advised the patron to seek competent advice before any commitment by contract to building, on all matters of form and size, materials and their cost, and of course style. Social connections greatly influenced the appearances of some buildings in sixteenth-century France, where groups of amateurs and craftsmen convened to discuss ideal and practical matters,[14] but records of such collaborations do not survive for any Parisian hôtel although they must have taken place. Amongst the upper classes were men who had travelled and who had read Vitruvius and other architectural literature, but only rarely is there any trace of their taste, and their impact is impossible to judge.[15] Only in the case of Pierre Lescot, the designer of the Louvre, do we have an exceptional and spectacular case of a courtier prevailing in favour over the specialized architect who, in the early history of the new Louvre, was Sebastiano Serlio.[16] The most common and convenient intermediary for a patron was his notary, the man who for all important contracts drew up the terms to be agreed between patron and master mason, and their growing expertise in the economics of building led to the

appointment of notaries to the senior post in the Royal Works under Henri III and Henri IV. The building contract may or may not mention a drawing on which the agreement has been based, and contracts are never good records of the stylistic details of buildings, for they are concerned with type, quality and price of materials, but contracts are invaluable for information about the dispositions of a house, and without them few reconstructions of the plans of lost buildings could be attempted. In such precise and detailed documents as Parisian masonry contracts it is surprising and frustrating to find only the most cursory descriptions of the decorative elements of the projected building, as these would be agreed on the basis of a drawing provided by or on behalf of the patron, and which would be initialled by all the parties to the contract. The loss of the drawings once attached to contracts in the notarial archives is almost total, and so it is from the costings, and the amount of more expensive toises , that a notion of the architectural interest of a building can be extracted. These documents almost never specify the particularities of any classical ornament to be made; whether a column or pilaster was to be Doric, Ionic or Corinthian presumably had little bearing on the amount of money involved in a bargain. The notarial building contract gave the patron assurances on the cost of work and on the date on which work would be started. Many contracts only describe a portion of a full scheme foreseen by patron, architect or master mason. The story of sixteenth-century architecture in Paris is full of curious fragments and never completed hôtels and judgements on the success or failure of a design should be cautious.

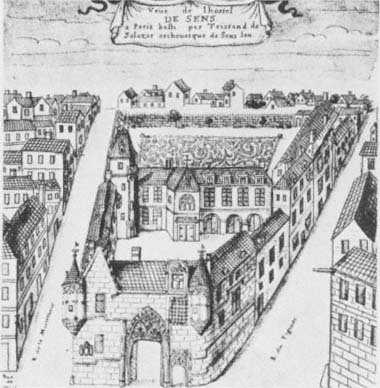

19

Hôtel de Sens. Ground-floor plan with supposed original dispositions.

20

Hôtel de Sens. Bird's-eye view by Gaignières.