Temperate Sea Beaches And Dunes

Mid-Atlantic Barrier Islands, United States

(Dolan et al. 1977, 1980; Leatherman 1979; Martin 1959)

A chain of barrier islands, with salt marshes and lagoons behind them, lies along much of the mid-Atlantic coast of the United States. Beaches are composed mainly of quartz sand, much more easily moved by the wind than the calcareous sand typical of tropical beaches. As a rule, dunes begin not far above the normal high water mark, leaving only a narrow, discontinuous storm beach at the top of the foreshore. This precarious habitat has a small but distinctive native herb flora. Some species are annuals, for example, sea rocket, Cakile edentula ; seaside spurge, Euphorbia polygonifolia ; and a rare beach pigweed, Amaranthus pumilus . Others are perennials, for example, beach pea, Lathyrus japonicus , and beach sandwort, Honkenya peploides . Only the Amaranthus is endemic; most are shared with beaches of the Great Lakes. Lathyrus and Honkenya are circumboreal.

The dunes form primarily under coarse rhizomatous grasses: in the north, beach grass, Ammophila breviligulata , shared with the Great Lakes and the Atlantic coast up to Newfoundland; in the south, sea oats, Uniola paniculata , shared with the Gulf of Mexico coasts as far down as Tabasco. Both are capable of virtually unlimited horizontal and vertical growth. Thriving under sand burial, they build high, steep dunes. These dune grasses grow in irregular clumps and patches, leaving many bare pockets and swales. Toward the dune front, these bare places have scattered individuals of the

same plants that colonize the storm beach. More protected swales and older dunes to the rear have a much richer flora. A few members of this flora are primarily coastal species: salt marsh cordgrass, Spartina patens ; beach plum, Prunus maritima ; bayberry, Myrica pennsylvanica ; beach heather, Hudsonia tomentosa ; and seaside goldenrod, Solidago sempervirens . These have wide coastal ranges outside the mid-Atlantic region and most also occur in scattered inland saline and sandy habitats. The bulk of the species present in the inner dune flora are primarily inland in distribution. Some are pioneers of open habitats, for example, little bluestem, Andropogon scoparius ; red cedar, Juniperus virginiana ; and poison ivy, Rhus radicans . In protected dune hollows, forests develop that have wind-shorn tops but share tree species with inland forests.

Prevailing winds are generally offshore, thus, traumatic events for the beach and dune vegetation are concentrated during storms. Occasional tropical hurricanes, with huge waves superimposed on storm surges, cause washovers and sometimes cut new inlets clear through barrier islands. Each year, 35 to 40 ordinary winter cyclones have onshore winds and waves strong enough to erode beaches. Occasionally one of these causes catastrophic erosion and washovers comparable to hurricane effects.

These barrier islands are believed to be inherently unstable and, in the long run, not under control of the vegetation. Large masses of sediment were moved landward during the great postglacial rise in sea level. About 6,000 years ago, as sea level began to stabilize at nearly its present level, waves, longshore currents, and winds working together formed barrier islands from the surplus sand. As long as the inshore zone contained sufficient sand, the islands built seaward, with the oldest, highest dunes at the rear. This progradation continued until about 2,000 years ago when the islands were much wider than now. Thereafter, net removal of sand offshore began; also blowouts and washovers pushed some sand over the islands into the lagoons. Thus, at present the islands are becoming narrower and migrating landward. As the islands become narrower, washovers are becoming more frequent, causing extensive burial by sand of the salt marsh vegetation along the lagoons. In the southern part of the region, marsh plants, including Spartina patens and Solidago sempervirens , commonly survive in the washover fans by upward regrowth. In the northern part, overwash fans are often colonized by Ammophila breviligulata , initiating a new, inner line of dunes. Remains of former inner dune forests are being exposed on some eroding foreshores.

Air photography is now being used to monitor shoreline changes over a 630-km reach of barrier islands. Transects at 100-m intervals, 6,300 in all, have been plotted spanning 15 years for the whole island chain and 30 years for much of it. Overall retreat averages 1.5 m/year, with more rapid retreat toward the northern ends of most islands and some accretion toward the southern ends. Retreating roughly 1 mile per century, changes are obvious

to residents. Inevitably, attempts to stabilize the islands are being made. A common approach is to develop continuous stands of dune-building grasses by planting, fertilizing, and watering. This commonly produces a higher, steeper foredune. With greater shelter from the foredune, vegetational succession at the rear proceeds toward an inland forest type. However, since the sand budget is not balanced, the steepened foredune is expected eventually to be undercut and washed away by storm waves, with complete washover of the islands following.

Mustang Island, Texas

In 1959, I laid out what were intended to be permanent 1-m-wide belt transects across the dunes of Mustang Island off Corpus Christi Bay. As usual on Texas barrier islands, there was a gently sloping intertidal beach, about 20 m wide. Just above normal high tide mark and at the base of the abruptly rising foredune there were a few widely scattered plants of Cakile geniculata and Amaranthus greggii , annual herbs endemic to Gulf of Mexico beaches on both sides of the tropics. The dunes were dominated by Uniola paniculata (discussed in the preceding section), joined here by the pantropical Ipomoea pes-caprae and the Caribbean Croton punctatus . On the backslope of the foredune were scattered grasses and dicot herbs, such as Spartina patens, Sporobolus virginicus, Oenothera drummondii , and Heterotheca latifolia . About 20 or 30 m behind the foredune, stabilized dunes had dense vegetation in which the outpost species were joined by Physalis viscosa, Rhynchosia americana, Ambrosia psilostachya , and a variety of other species. Nearly the whole assemblage was shared with the tropical Gulf coast. The transects were based on a government triangulation structure and were staked.

In 1961, the eye of Hurricane Carla crossed the coast close to the study site with winds of about 275 km/hr and waves reaching 7 m above ordinary high water mark. In 1962, the triangulation structure and stakes had disappeared and the transects could be only approximately relocated. Instead of being abut 20 m wide, the intertidal bare beach was now 80 to 90 m wide, extending clear through what had been the foredune zone and into the formerly stabilized dunes behind. Above a steep sand bank, freshly cut by the storm waves, the old dune vegetation appeared undamaged. At the top of the new beach and at the base of the cut bank, there were a few isolated seedlings of Sesuvium portulacastrum and Ipomoea pes-caprae and some resprouting rhizomes of Uniola and Spartina . Near the transected area, where washovers of barrier islands had occurred, seedlings of various beach outpost species were colonizing bared areas far back in the wrecked dunes, the seed presumably having ridden in on the storm waves.

Intercontinental Migration of Ammophila

(Cooper 1958; Dicken et al. 1961; Franklin and Dyrness 1973; McLaughlin and Brown 1942; Rosengren 1981; Sweet 1981)

Marram grass, Ammophila arenaria , native to western Europe, is even more vigorous as a dune builder than the eastern North American A. breviligulata (discussed above). Marram grass has been widely planted for dune stabilization. Where it has been introduced, it commonly has naturalized and spread.

On the Atlantic coast of the United States, marram grass is now naturalized locally, but has not generally displaced its native congener. On the Pacific coast, it has widely displaced a native dune grass, the circumboreal Elymus mollis , which is a relatively weak dune builder.

The amount of sand carried down western North American rivers was drastically increased during the nineteenth century by hydraulic mining, grazing, logging, and farming. Beaches near river mouths built out faster than vegetation could follow and surplus sand moved inland in great sheets and moving dunes. Starting in 1869, the active dune field that was to become San Francisco's Golden Gate Park was stabilized by planting marram grass. Soon after, the Coast Guard planted it to stabilize dunes along Humboldt Bay in northern California. Between 1910 and 1934, the Forest Service, other government agencies, and property owners planted marram grass on many dunes along the Oregon coast. Beginning in 1935, a huge dune field on the Clatsop Plains, south of the Columbia River mouth, was planted with marram grass. The eastern North American Ammophila breviligulata has also been planted on Pacific coast dune fields, but to a much lesser extent.

At the present time, Ammophila is thoroughly naturalized on innumerable stretches of the Pacific coast and has become a powerful geomorphic agent by building fairly continuous wall-like foredunes, which were not previously characteristic of this region. Sheltered behind these walls, formerly active sands have become vegetated with a mixture of native and exotic species. Prominent among these is Scotch broom, Cytisus scoparius , native to sands and sea cliffs of western Europe, which was also deliberately introduced in the late nineteenth century for sand stabilization and has now become thoroughly naturalized.

Marram grass has had a similar history in temperate Australia. Two native Australian beach grasses, Spinifex longifolius and S. hirsutus , are moderately effective sand binders, but they do not form steep, stabilized dunes as Ammophila does. Ammophila is currently replacing Spinifex hirsutus at latitudes above 33°S on many Australian beaches. Substituting stabilized linear foredunes for active transverse dune fields allows advance of woody inland

vegetation, especially Acacia spp. at the expense of various beach pioneer species.

Naturalization of Chrysanthemoides , Australia

(Gray 1976)

Chrysanthemoides monilifera is a shrubby composite native to the temperate southeastern coast of Africa, where it grows behind the storm beach on dunes and sea cliffs. The seeds are not buoyant and are probably bird dispersed. The species spreads vegetatively with vigor.

The species has been cultivated in the Sydney Botanical Garden and elsewhere in Australia since the late nineteenth century. Early in the present century, it escaped to beaches in New South Wales and on Lord Howe Island offshore. After 1950, it was much planted by the Soil Conservation Service to stabilize dunes and revegetate sand mining areas. This planting was stopped when it was found that Chrysanthemoides was invading and in places eliminating the complex native dune flora. In 1981, I saw several dense pure stands of this exotic on New South Wales beaches between 28° and 36°S latitudes, but none on any Queensland or Victoria beaches.

A reciprocal invasion of native South African coastal vegetation by introduced Australian Acacia cyclops and A. saligna is out of control (Taylor 1978).

Naturalization of Mesembryanthemum , California

(Blake 1969; Ferren et al. 1981; Moran 1950; Vivrette and Muller 1977)

The genus Mesembryanthemum s.l. (sometimes split into more than 100 genera) has thousands of species native to South Africa. Many of these are widely cultivated by fanciers of succulent plants. For example, M. edule (= Carpobrotus edulis ), native to the Cape Province and Natal, has been cultivated in Europe since the seventeenth century and in Australia and California since the nineteenth century. Although now widely naturalized there on sea beaches, it is generally recognized as an exotic that has escaped from cultivation.

Migration of a species very closely related to Mesembryanthemum edule , namely M. aequilaterum (= Carpobrotus aequilaterus ) is problematic. It is not known from South Africa and is generally considered to be native to either Australia, Chile, or California, or all three. The species was described in 1798 by Haworth from plants cultivated in England that were reported to be

"native to the country around Botany Bay." Either by oceanic drift or by transport on a ship, the species reached Chile before 1810, when it was collected at Valparaiso and named M. chilense . The first California record is from Bodega Bay in 1841. There are various plant species that apparently have naturally disjunct ranges between Chile and California, presumably due to dispersal by migratory birds. However, in this particular case, nineteenth-century human introduction appears likely. Mesembryanthemum aequilaterum is still actively spreading on the California coast. For example, at Point Dume in Los Angeles County, local residents have observed its expansion; in what was planned as a natural coastal reserve, it is spreading as a thick blanket that is overwhelming the native dune vegetation. However this species reached Chile and California, it seems that it originated in Australia along with several very closely related species that are Australian endemics. One of these, M. glaucescens (= Carpobrotus glaucescens ), appears in a water color painted at Sydney by Governor Arthur Philip about a year after the arrival of the first British colonists. The progenitor of these endemic Australian species must have come from South Africa long before, perhaps by oceanic drift.

Several other Mesembryanthemum species that are known to have been imported from South Africa have escaped from cultivation and are naturalized along the coasts of California, Baja California, and the offshore islands, for example, M. crystallinum and M. nodiflorum , which have been spreading since 1890, and M. croceum , which has been spreading since 1940.

Naturalization of Cakile , Australia and Western North America

(Barbour and Rodman 1970; Rodman 1974)

Various species of Cakile , the sea rockets, grow as extreme outpost pioneers on storm beaches. As noted in the Introduction, they have a peculiar mechanism for dividing their seeds between in situ reproduction and sea dispersal. Part of the seed is buried with the dead annual parent and part floats away, remaining viable for at least 10 weeks in seawater, but germinates only after being stranded and rained upon.

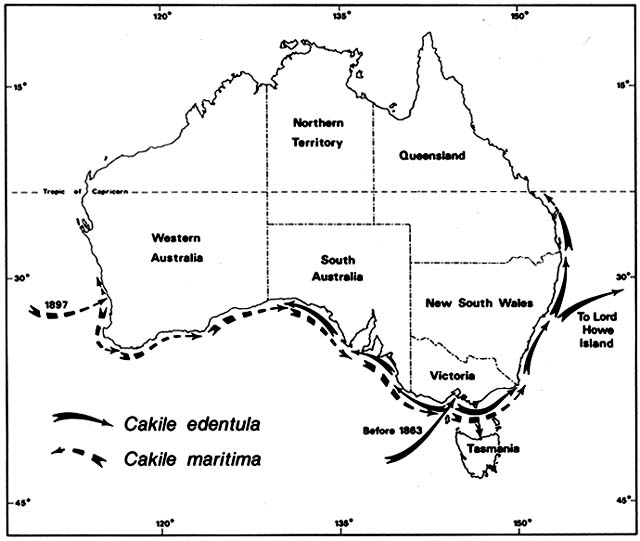

Cakile edentula is native to the Atlantic coast of North American from Labrador to Florida and the shores of the Great Lakes. In Australia, it appeared near Melbourne before 1863 and near Sydney by 1870, supposedly brought in sand ballast by an American sealing ship. It soon spread on its own to all the southeastern Australian states, including Tasmania, and to Lord Howe Island (fig. 3). By 1922 it was moving north along the temperate Queensland coast and by 1960 reached Heron Island on the Tropic of Capricorn. In 1981, I did not find it on any tropical Queensland beaches. Moving

Figure 3. Naturalization of Cakile on Australian Beaches. Temperate beach species have repeatedly found open

niches distant from their native ranges following introduction by human agency. Two species of sea rockets that

arrived in Australia in the late nineteenth century spread by sea dispersal from their entry points along Australian

beaches, often advancing at a rate faster than 50 km/year until reaching their climatic limits. These grow closer to the

sea than native beach plants.

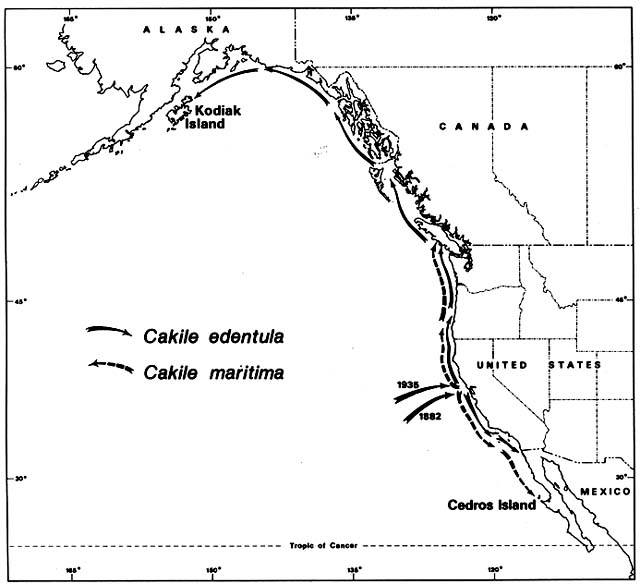

Figure 4. Naturalization of Cakile on Western North American Beaches. The sea rockets that invaded Australian

beaches were also accidentally introduced to the California coast. Cakile edentula from the Atlantic coast of North

America arrived first in San Francisco Bay. It then spread rapidly northward and southward. Before its migrational

history was investigated, some botanists mistook it for a native. Cakile maritima arrived much more recently from

Europe and has always been recognized as introduced.

westward from Melbourne along the south coast, C. edentula met and mixed with another invading sea rocket, C. maritima , which was moving in the opposite direction.

Cakile maritima is native to the Mediterranean and Black seas and to the Atlantic coasts of Europe as far north as southern Scandinavia and Scotland. It arrived at the port of Fremantle, Western Australia, by 1897. By 1963, it was ubiquitous on Western Australia beaches from 31°S southward; I found it on every one of 18 beaches studied in this region. Moving eastward along the south coast, C. maritima had entered South Australia by 1918 and Victoria by 1922. For a while, C. maritima and C. edentula shared the coasts of South Australia and Victoria, but C. martima now has sole possession of these Mediterranean type, dry summer coasts. Cakile edentula remains dominant along the temperate east coasts of New South Wales and Queensland, where summers are wetter.

On the Pacific coast of North America, the same sea rockets have immigrated in a pattern remarkably parallel to that in Australia. Again, Cakile edentula arrived first (fig. 4); the earliest record was on the Berkeley shore of San Francisco Bay in 1882. By 1891 it was common around the Bay, and outside the Golden Gate it had moved 30 km south to Half Moon Bay. By 1906 it had arrived at San Diego, where its southward expansion ended. By 1952 it was on the Channel Islands off the coast of southern California. Meanwhile, moving northward from San Francisco, it arrived in Oregon by 1901, Washington by 1907, British Columbia by 1909, and Kodiak Island off Alaska by 1931. The northward expansion had averaged 65 km/year over a 50-year period.

Local botanists, aware of the rapid spread of Cakile edentula , recognized it as an immigrant. However, the then dominant Harvard taxonomist, M. L. Fernald, temporarily confused the story by suggesting the Pacific coast populations belonged to a native endemic variety, which he named C. edentula var. californica . He postulated a formerly continuous boreal range, which became disjunct during the Pleistocene, a concept closely related to his nunatak hypothesis for other North American disjuncts. This variety is no longer considered distinguishable from the species proper.

The European Cakile maritima arrived in California so recently that no botanists have mistaken it for a native. It was first recorded in 1935 on a popular beach 25 km north of San Francisco. It spread almost as fast as C. edentula , averaging about 50 km/year in both directions. Northward it reached British Columbia by 1951, and southward it reached Cedros Island off the coast of Mexico by 1963. As in Australia, C. maritima almost completely replaced C. edentula in the region of Mediterranean type, dry summer climate. From Oregon northward, in areas with summer rain, C. edentula has remained predominant.

In both Australia and western North America, if only the present, static distributions of the two sea rockets were known, their nearly discrete ranges would appear to be directly controlled by climate. However, the actual history shows that Cakile edentula was quite successful outside its present climatic limits before the arrival of C. maritima . The outpost zone on a storm beach would at first glance seem one of the last places in the world where competitive displacement of one species by another would take place. Only a small part of the area is occupied by plants and for only part of the year. Nevertheless, if we recognize that the beach is not homogeneous, that there may be very limited safe sites for sea rocket establishment, and that the expanse of bare sand may be an uninhabitable wasteland for both species, we can visualize fierce competition in spite of low population density.

Comment

Temperate beach plants, like tropical ones, are relatively indifferent to rainfall gradients provided there is enough rain to maintain a freshwater supply under the sand. The greater seasonality of temperate coasts probably affects beach plants mainly via changing wave energy. Lacking fringing coral reefs, temperate beaches commonly have an annual cycle of strong erosion and accretion. Also, temperate zone beaches are generally composed mainly of quartz sand, which is more restricted in distribution in the tropics. Quartz sand is transported by longshore currents and is easily moved by the wind when dry, unlike calcareous sand, which is of local origin and normally immobile under the wind. Thus, many temperate barrier beach and dune systems are relatively extensive and dynamic. In spite of this, their floras are relatively poor in primarily coastal species except in South Africa and Australia, regions that are also phenomenally rich in primarily inland floras on ancient sand plains.

The primarily coastal, drift-dispersed outpost species have less broad and disjunct ranges in temperate than in tropical regions. A few that now have disjunct circumboreal ranges may be relicts from ancient distributions along former seaways. Similarly, the eastern North American beach species that now have disjunct ranges on the Great Lakes and Atlantic coast may have colonized the interior in early postglacial time when a marine embayment provided a continuous route, subsequently broken by isostatic uplift (Rodman 1974). Clearly, this species group is dependent not on salt water or salt spray but on waves, wind, and moving sand to create its habitat.

Like tropical beach pioneers, temperate outpost species need drift dispersal to occupy a dynamic and discontinuous habitat, but the temperate species have seeds that are buoyant for a shorter time. Perhaps this is because seeds

floating longer distances in temperate latitudes would have less chance of survival because the prevailing currents run north and south along the coasts rather than east and west through island stepping stones. The examples noted above of naturalization and spread following artificial introduction to distant regions demonstrate that the species had been unable to reach parts of their potential areas by natural long-range dispersal. They also demonstrate these species' capacity for rapid stepwise migration along a coastline and to offshore islands. Many similar cases, not discussed above, are known, for example, naturalization of Artemisia stelleriana and Carex kobomugi , native to northeastern Asia, on eastern North American beaches, and naturalization of Rumex frutescens , native to temperate South America, on British and Danish dunes. Some of these naturalized exotics have found an unoccupied niche closer to the sea than the native beach vegetation; others have invaded and displaced native dune species.