I. Historic, Political-Economic, and Social Levels of Experience

2. The Political Economy of the Sambirano

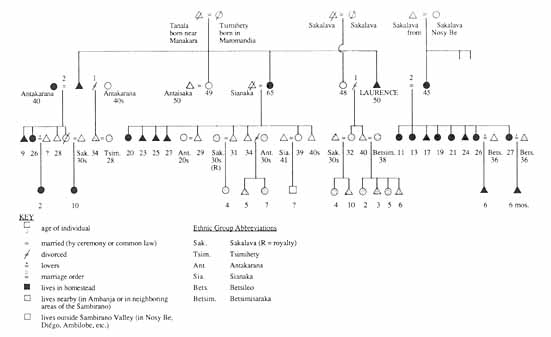

The Sambirano Valley is one of the few regions of Madagascar where one finds evidence of prosperity. Malagasy often refer to this region as one of the most fertile and productive areas of the island, providing a sharp contrast to the rest of the nation. The town of Ambanja lies in the heart of this river valley and is the commercial, political (including royal), religious, educational, and entertainment center for the region. Even though national trends exhibit a downward movement of the economy, the Sambirano has become well-known as a region where “there is work” and “money” (misy asa,misy vola), so that many people have come here from other regions of the island to “seek their fortunes” (hidaty harena). On the whole this nation is plagued by fierce shortages of such essentials as foodstuffs, medicines, and construction materials, but in Ambanja one is struck by the relative beauty of the area and plentitude of goods—though overpriced—that are available. In comparison to other regions of Madagascar, the development that has occurred in Ambanja and the Sambirano Valley is striking. This chapter will explore the factors that account for this over time.

| • | • | • |

Ambanja, A Plantation Community

The greatest economic force existing in the Sambirano Valley is that exerted by the enterprises, the large companies that own much of the land in the valley. Originally these were private plantations, established by foreign planters around the turn of the century. Following the Socialist Revolution of the 1970s, many foreign nationals fled the country, their lands confiscated by the state. By the late 1970s nearly all of these plantations became fully or semi-nationalized, and today they are managed by Malagasy rather than foreign staff. The shift from private holdings to state capitalism has had an effect on land tenure and work relations; it is also important for understanding Malagasy notions of historical experience. For this reason, throughout this study I will use the term plantation when referring to these farms during the colonial (1896–1960) and early postcolonial (1960–1972) eras, and enterprise when speaking of the period since the Socialist Revolution (1972 to the present).

The plantations (and, more recently, the enterprises) have transformed the geography of the region and shaped, directly and indirectly, the economic, political, social, and cultural orders of the region. Their activities have been characterized by intensive development, the landscape transformed within a few decades into large estates of manioc and sugar cane and, more recently, cocoa, coffee, and perfume plants such as ylang-ylang. During the colonial period, Sakalava living throughout the valley were relocated to make room for plantation lands. Sanctioned by French colonial policies, the activities of the plantations led to the introduction of foreign capital and the proletarianization of local and migrant labor. Colonial efforts to undermine the authority of local royalty also caused the breakdown of local, indigenous power structures and, ultimately, Sakalava cultural identity. As a result of plantation activities, by the 1920s Ambanja had also become a major religious center for the Catholic Church and the district headquarters for the colonial administration. The presence of these forces in the Sambirano has contributed, to a large extent, to the establishment and growth of Ambanja as a major northern urban center.

The Town and its Environs

Regardless of the direction that one takes out of town, the view is the same: shady, damp forests of cocoa and coffee. Almost all of these lands belong to the enterprises. Occasional breaks in the fields of cocoa and coffee reveal independent villages, a handful of small company worker settlements, and rice fields, fruit trees, or stumpy and gnarled trunks of ylang-ylang. There are also the administrative and production centers of the enterprises. Here one finds warehouses where produce is collected, dried, and sorted by hand in preparation for export and concrete colonial-style villas with wide tin roofs and large verandas, which serve as the offices and housing for the management staff. The borders of the enterprises may be drawn where the terrain changes—at the steep ridge of the Tsaratanana mountains to the east; at the semi-arid terrain to the north and south, which is more suitable for wild cashews and for grazing hardy hump-backed zebu cattle; and at the mangrove swamps that flank the seacoast. In contrast to these bordering areas, the land throughout much of the valley is verdant and lush.

1. Main Street, Ambanja. Houses of the more prosperous families line this street, as do the offices and dwellings of the managers of the major enterprises in the Sambirano Valley. The shade trees on either side of the avenue are the same as those found in the fields to protect coffee and cocoa from the tropical sun.

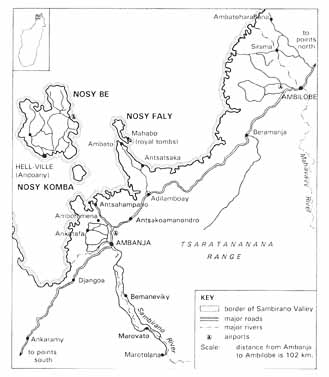

The town of Ambanja lies at a major commercial crossroads for the north (see figures 1.1, 2.1; plate 1). One may approach it from the port of Antsahampano (approximately fifteen kilometers to the northwest), from the national capital, Antananarivo, which lies to the south in the central high plateaux, and from Diégo, the provincial capital, which is a day’s drive (240 kilometers) to the north. Until a decade ago the only practical way to reach Ambanja from other parts of the island was to fly or travel by boat to the neighboring island of Nosy Be, take a ferry to the small port of Antsahampano on the main island, and then catch ground transport to town.

For a long time this road between the port and the town was by far the best in the area. It was originally constructed for the early plantations and it is still maintained by the enterprises, which use the port to export their produce. The significance of the role played by the enterprises in terms of road maintenance and construction was particularly evident in 1987 when telephone poles and electric wires were installed, stretching from Ambanja all the way to the port on the coast. This ensured that electricity eventually would be available for the inhabitants of the villages along the road. Nevertheless, such progress had its price, since the poles were mounted on the south side of the road, making it necessary to cut down fruit trees in private yards, while the northern side, where there are groves belonging to the enterprises, remained untouched. This road to the port is also used by many people wishing to travel by ferry to the nearby island of Nosy Be, which is both a tourist resort and a site for other large-scale enterprises that grow sugar cane. The ferry provides inexpensive and convenient transportation for passengers wishing to visit their kin or the shops on Nosy Be, while young people may make the journey to enjoy the nightlife of discos and organized parties (bals). Since land on this smaller island is at a premium, zebu cattle, bound for slaughter, are carried from the Sambirano on the boat’s lower decks to supply meat for local inhabitants and for the lucrative tourist industry.

Today the conditions of the roads of this region are exceptionally good, since Madagascar is a nation that relies heavily on air and sea travel and invests little in road development and repair. Only in the past few years have these been all-weather roads. For a long time they were little more than footpaths, and until very recently only cars equipped with four-wheel drive were able to traverse them with ease. Within the last decade these roads have been improved considerably, so that now they are graded and large portions are paved. Local Sakalava dislike this new development, fearing that good roads will only make it easier for migrants or vahiny from other parts of an otherwise extremely economically depressed nation to come here to settle.

The south-north road that runs through Ambanja is a major national route, and it is by means of this road that the majority of vahiny arrive in the valley from points south. In the past, the trip from the south was long and difficult: many traveled more than one thousand kilometers by foot in an effort to find work. Today most migrants come to this region by bush taxi (taxi-brusse) by way of the national capital of Antananarivo in the central highlands or from the southern coastal city of Mahajanga. There are also airports in Nosy Be and Diégo with runways equipped for landings by Boeing jets, and Ambanja has a small airport where propeller-driven Twin Otters land twice each week. The northern part of this route is used frequently by those who travel to the provincial capital of Diégo either for business or pleasure. This road is paved as far as the town of Ambilobe (102 kilometers). This town, like Ambanja, is a county seat, a slightly smaller commercial center, and the residence of the king of the Antakarana who inhabit the neighboring Mahavavy region. Near Ambilobe is another large sugar cane enterprise called Sirama.

2.1. Detail Map of Northwest Madagascar. Source: After Madagascar-FTM (1986).

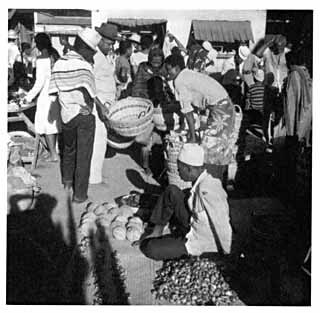

Approaching Ambanja from the south, one passes through fields of cocoa and coffee, crosses over the bridge that spans the Sambirano River, and then enters the oldest quarter of town. Here one finds the bazarbe, a wide and circular-shaped daily market. Ambanja is a major urban center of the northwest, serving as a county seat for the region, and offers many goods, services, and sources of entertainment that are unavailable in other regions of the island. This is immediately evident in the bazarbe. This market is surrounded on all sides by the concrete structures that house the shops and residences for Indian, Arab, Chinese, and Comorean merchants who first came to Ambanja after hearing of the development of the area by foreign planters. Behind the merchants’ shops, just to the west and beyond the bazarbe, the top of the Indian mosque can be seen. To the east is the petrol station, a soccer field, and the town cemetery, where a wall separates Christian and Muslim graves. On a Sunday afternoon in the dry season, the music at a morengy or boxing match can be heard playing in the distance. On most evenings a crowd will gather before City Hall to gaze at the color television suspended above the front door, while lovers and groups of teenagers stroll by or pause momentarily on their way to a disco or to the cinema. The bazarbe is also one of two stations for the bush taxis, the small Peugeot pickups that serve as the main form of ground transportation in Madagascar. Here in Ambanja they dart madly between the bazarbe and the Tsaramandroso, the site of the Thursday market at the other end of town (see plate 2).

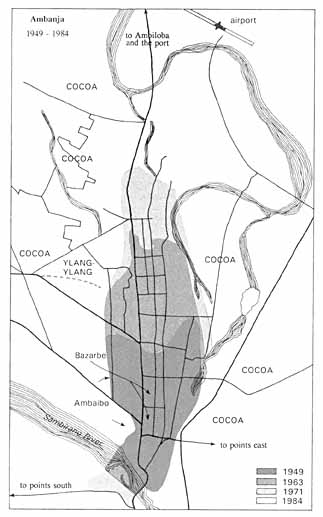

2.2. Map of the Town of Ambanja. Source: After Andriamihamina et al. (1987: 6).

The enterprises are a dominant force in the daily lives of all people living in the Sambirano, whether or not they are employees. The town itself is flanked on the east and west by enterprise lands that, in some places, border streets (see figure 2.2). As a result, urban growth has pushed south along the banks of the river and north following the main road out of town. There is some order to this development, for as neighborhoods expand they continue to form a rough grid of wide, unpaved, and generally very dusty streets. Nevertheless, for the most part, settlement patterns have been sporadic, haphazard, and random. Apart from the old quarter by the bazarbe, it is difficult to categorize any one neighborhood as rich or poor or populated by a majority of any one ethnic group. The structures of the town reflect this diversity. There are a few impressive and imposing two-story villas plopped down among neat two- or four-room houses—made either of corrugated tin or fiber from the traveler’s palm (Ravenala madagascariensis)—which rest on concrete foundations or on stiltlike wooden legs. Children, chickens, goats, geese, and ducks wander in and out of houses or root about in the grass beneath the shade of mango, banana, coconut, and jackfruit trees.

Since the Sambirano lies in northern Madagascar near the equator (just north of 14°S parallel), it is always hot in Ambanja. There are only two seasons here: the dry season from May to October, and the wet, hot season from November to April, which is accompanied by the threat of cyclones from December to February. Everyday greetings often include a commentary on the weather: in the dry season, “Ah, the heat, the dust!” (mafana é! misy poussière!), or, in the wet season, “Ah, the heat, the mud!” (mafana é! misy goda!). Most people prefer to walk along the main street, beneath straight, tall shade trees. These trees were planted earlier in the century, and are the same varieties which are used on enterprise lands to shade cocoa from the heat of the sun (again, see plate 1).[1]

2. Tsaramandroso, the site of the Thursday and smaller daily market. Here the multiethnic makeup of this community is evident, where Sakalava and migrants from other areas of the island come to buy and sell wares as well as to socialize.

It takes about twenty to thirty minutes to walk, at a leisurely pace (mitsangantsangana), from one end of town to the other by way of the main street. Lining this street are small shops that sell colorful fabrics and household necessities; hotely, or the small bars and restaurants; the colonial style, wooden homes that belong to select royal families; the impressive and freshly painted structures of the Peasant’s Bank and the county seat; a variety of mosques and Protestant churches; and the courthouse, gendarmerie, and prison. All of the enterprises have an office centrally located in Ambanja, since the directors prefer to live in town. These offices are generally placed on the ground level of an imposing villa. Here on the main street there are also offices and agricultural experimental stations of a variety of government ministries, so that as you follow the main street you can see cocoa growing and can smell the pungent blossoms of ylang-ylang.[2]

All along this main street women and young girls sell snacks to passersby, and there is usually a considerable gathering of their stands placed strategically so as to draw clients from the local schools and the municipal hospital. Near the latter is the private occupational health clinic established for the workers and their families and funded by member enterprises and local businesses. Across the street are the grounds of the Catholic Mission school and printery and the tallest building in town, the cathedral. Behind it is the Catholic hospital, which, when completed, will provide the first operating room facilities in the area.[3] Near the other end of town is the Thursday market, (again, see plate 2) where one finds a cluster of oxcarts, yet another bar, the office of Air Madagascar, and many houses of all sizes extending to the town border and beyond. If one visits this second market early in the morning or at dusk, bright red flatbed trucks from the enterprises will have stopped there and men and women—some with small children—will be climbing in or out on their way to or from work.

| • | • | • |

An Economic and Political History of the region

Precolonial History: The Bemazava-Sakalava[4]

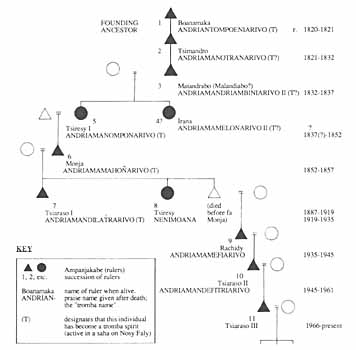

When French military troops arrived in the Sambirano in 1896, this valley was indisputably the territory of the Bemazava, the northernmost dynastic branch of Sakalava speakers, who today form the fifth largest of the eighteen officially recognized ethnic groups of Madagascar (Covell 1987: 12).[5] The Sakalava as a whole are organized as a collection of kingdoms occupying the island’s west coast, having been formed as a result of disputes over succession and the subsequent movement north by new founding dynasties.[6] The Bemazava-Sakalava trace their origins to Boina, the royal and sacred capital that lies near Mahajanga on the central part of the western coast. The Bemazava dynasty was established by Andriantompoeniarivo (see figures 2.3, 2.4).[7] According to oral tradition, he left Boina following a dispute over royal succession. Andriantompoeniarivo was accompanied by his followers and by a powerful moasy (HP: ombiasy) or herbalist named Andriamsara. As they traveled they carried with them royal relics, and among these was a container of sacred water. When the party reached the river valley, however, they discovered that the container had run dry. While trying to decide whether or not to turn back or to use the local river water to replenish their supply, Andriantompoeniarivo is said to have remarked, “it makes no difference, they are each/both water” (samy ny rano). Thus the Sambirano River was named, and it is here where they chose to settle.[8]

In the nineteenth century, just prior to French conquest, the Bemazava lived in small villages that were scattered throughout the Sambirano. They farmed plots of dry rice and manioc, banana, and other fruits, but the majority of the land of this fertile alluvial plain was used to graze herds of zebu cattle (see Dury 1897). The Bemazava of the Sambirano appear to have been united into a loose confederation under a common ruler (ampanjakabe) who was the living successor of the tromba or spirits of the royal ancestral dead. An important royal duty involved the ruler serving as the representative for his or her living subjects in ritual contexts. It was the ruler, with the help of assistants (male assistant: ngahy; female assistant: marovavy or ambiman̂angy) and tromba mediums (saha), who invoked the royal spirits. The ruler also served as a mediator and judge in secular disputes. The Bemazava ruler lived in the coastal village of Ankify, while the island of Nosy Faly served as the sacred ground where royal dead were entombed and where the mediums for the greatest of the royal tromba spirits resided. On Nosy Faly the first Bemazava king, Andriantompoeniarivo, was laid to rest, along with his successors and other members of the royal family (ampanjaka). Today both Andriantompoeniarivo and Andriamsara are regarded by the Bemazava as their founding ancestors. They are the most important of the local Bemazava tromba spirits, and their mediums live on the sacred island of Nosy Faly. As will become clear in Part 2, these spirits and their mediums wield much power in the Sambirano.

2.3. Sakalava Dynasties of Madagascar. Sources: De Foort (1907: 130); Feeley-Harnik (1991: 80) after Guillain (1845); Ramamonjisoa (1986: 101).

Prior to 1896, the Bemazava were well aware of the existence of the French, who had been active in the north for approximately sixty years. The queen of another branch of Sakalava—the Bemihisatra of Nosy Be—had previously invited the French to her island. In so doing, she sought to gain a powerful ally against her enemy, the Merina of the central high plateaux (see Mutibwa 1974 for a discussion of Merina expansion in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries). She extended this invitation to the French only after she had failed to acquire firearms from the Sultan of Muscat: giving way to his conditions, she and other Bemihisatra royalty agreed to convert to Islam, but the Sultan only sent velvet hats, not arms (Dalmond 1840). In 1840 the French established their first permanent settlement on Nosy Be, and the members of this party included Jesuit missionaries and planters. The latter started sugar cane plantations that still exist today (they are administered from the town of Djamanjary). Although the Sambirano was not far from Nosy Be, contact between Bemazava and Europeans remained fairly limited due to the relative difficulty of traveling to the interior, and to the reputation of the fierceness of Bemazava warriors.

The Establishment of French Control

The end of the nineteenth century marks the beginning of the colonial era in Madagascar. In 1895 Madagascar was declared a protectorate and, in the following year, a colony of France. Under the direction of the military strategist Général J. S. Galliéni, the Merina monarchy was abolished and the queen, Ranovalona III, exiled to Réunion. French troops marched from one end of Madagascar to the other as part of Galliéni’s pacification program. Galliéni sent military expeditions to comb the entire island, collecting enormous quantities of data of strategic import, making note of relevant social and cultural institutions, and eventually setting up a network of military posts. From records made by commanding officers, it appears that the Sambirano was visited twice, one battalion moving west from the Tsaratanana ridge to Nosy Be, the other moving up from the ancient northern Sakalava capital of Boina (Boucabeille 1897; Brown 1978: 236ff; Dury 1897; Galliéni 1900, 1908; Raolison 1966; see also David-Bernard 1943). Lieutenant S. V. Dury, who led the battalion from the east, described the Sambirano as follows:

Dans ces plains [Sambirano and neighboring ones] l’herbe est abondante en toute saisons, ce sont des pâturages magnifiques, qui nourrissent les troupeaux les plus beaux et les plus nombreaux qui existent de la Mahajomba [Mahajanga] au Sambirano. Les boeufs y sont superbes et donnent de 100–150 kilos de viande; on les vends sur place 20 Francs du maximum.…Cette region du Sambirano est donc aussi très riche. Le débouché vers la mer, qui donne dans la large baie de Passandava, est commode et la construction d’une route simplement. (Dury 1897: 443, 445)

It was in 1896 that the first military post, under the command of Captain Verdure, was established in the Sambirano area in the village of Ambato. Ambato lay near the coast en route to the sacred island of Nosy Faly, the location of the Bemazava-Sakalava royal tombs. Within a few years, military men—some with families—had started to farm in the area, and by the turn of the century the Sambirano had become attractive to planters from the neighboring islands of Nosy Be, Réunion, and the Seychelles. In 1903 the French moved the military post to a more advantageous location inland and upstream and situated on a high hill that provided a spectacular view not only of the river but of the entire valley. Placed strategically at a major crossroads, it is around this post that the town of Ambanja eventually grew. From the buildings constructed by the French one may now look down upon the oldest quarter of town which encircles the bazarbe. Throughout the colonial era the post’s buildings served as the residence for French colonial officers; since Independence they have been used to house local Malagasy civil authorities.

By the late 1890s, the government of France began to grant land titles to foreign-born planters, titles that were authorized by Galliéni and issued from the national capital of Antananarivo. Within a few years the majority of the land that previously had been used and occupied by Bemazava had been transformed into large private plantations. Much of this land was acquired through purchases of communal grazing lands, transactions the Bemazava misunderstood. Many Bemazava were forced out of the choicest areas of the valley and onto indigenous reserves (FR: reserves indigènes), often pushed up against steep hillsides that were difficult to farm and unsuitable for grazing cattle. This policy of designating territory as indigenous reserves was unique to the northern and western provinces of Antsiranana (in which Ambanja is located), Mahajanga, and only a few areas of the high plateaux. Furthermore, Nosy Be and the Sambirano each had over twenty reserves, while Mahajanga had only two (Service Topographique, Nosy Be, n.d.). This period is also marked by a large exodus of Bemazava to the drier Mahavavy area that lies one hundred kilometers to the north in Antakarana territory. By the 1920s the Sambirano Valley had developed into one of the most prosperous areas of Madagascar. Merchants with origins as diverse as southern China, southern India, and Yemen came and settled permanently in the town, establishing a large market (the bazarbe) beside the river and just below the military post.

The Development of the Sambirano

It is important to realize that the development of Ambanja into a town and commercial center occurred as a result of, first, French occupation of the region and, second, the subsequent activities of the early plantations. Although it is possible that there was a Bemazava village at this location prior to the arrival of the French, a surveyor’s map drawn at the turn of the century depicts simply a military post with a flagpole to mark it. As the town has grown, it has developed along a clear axis, sandwiched between the fields of the large plantation fields of the enterprises that flank it to the east and west (figure 2.2).

The activities of a number of other foreigners reveal that Ambanja was growing rapidly into an important cosmopolitan center. The Catholic Holy Ghost Fathers from France were soon active here: in 1921 they performed their first Catholic marriage, and in 1936 they completed the construction of the cathedral. By 1927, surveyors were employed to measure property systematically and lay down landmarks for both private individuals and the owners of plantations, who thus acquired official deeds to their lands. An early road map of Madagascar, published in 1938, categorizes Ambanja as a commercial center, complete with a post office and lodging for weary travelers.

The development of the Sambirano into a plantation area was shaped primarily by two men, Louis Millot and Guy de la Motte St. Pierre. By 1905, each had acquired land grants from France which together covered nearly all of the Sambirano Valley. In the next few years Millot and de la Motte St. Pierre also bought out other smaller planters when their efforts to farm failed.[9] By the 1920s a third plantation had become active in the Sambirano, one that is now known as the Compagnie Nosybéenne d’Industries Agricoles (CNIA). This was an extension of Djamanjary Sugar in Nosy Be.

Both Millot and de la Motte St. Pierre began by planting what was locally available. Millot chose his fields carefully, and it is said that he sent soil samples back to Europe for analysis before making large investments in his lands. He began by planting coconut palms, rice, and manioc for the production of tapioca. By the the 1930s, he had imported cocoa plants from the Ivory Coast, and today cocoa remains the dominant crop on Millot lands. In more recent years, this enterprise has also planted some pepper, as well as fields of perfume plants. De la Motte St. Pierre also started with coconuts, but soon switched to sugar. With the arrival of CNIA in the 1920s, sugar remained the dominant crop of the Sambirano until the 1940s.

After World War II, when the price of sugar fell on the world market, it was decided that the sugar companies on Nosy Be, near Ambilobe, and in other regions of Madagascar were sufficient to satisfy the exports needed from Madagascar. As a result, plantations in the Sambirano cut back on sugar production, cocoa production was expanded, and coffee was introduced as a new crop. Eventually cocoa and coffee replaced sugar altogether as the major export crops of this region. Although French planters maintained a monopoly over cocoa production, by the 1950s the government was also encouraging private farmers who had small plots to grow coffee as a cash crop. Tapioca production continued to be a major industry in the Sambirano until the 1970s, when the last factory shut down in response to a diminishing market. Meanwhile, within the last two decades, cashews—which grow wild in the drier areas to the north and west—have joined coffee and cocoa as one of the region’s three major export crops. As will become clear, coffee and cashews are important in Bemazava-Sakalava constructions of their local history. The meanings associated with common historical experience are played out through tromba possession, where coffee and cashews figure as prominent symbols (see Part 2).

Following the Socialist Revolution in 1972, all of the large plantations except E. Millot were seminationalized.[10] Millot and the now combined businesses of CNIA/SOMIA (Sociéte Malgache d’Industrie et d’Agriculture) are the largest and most impressive enterprises in the Valley.[11] These have grown out of the original farms of the two men, Millot and de la Motte St. Pierre. The plantation E. Millot had more than seven thousand hectares at its height in the 1940s, although it is now down to two thousand. CNIA/SOMIA, which possesses much of de la Motte St. Pierre’s original lands, at one time boasted close to a million hectares.[12] In the Sambirano there are also a number of smaller enterprises, small private farms, and companies (referred to as concessions) which buy agricultural produce and prepare them for export.

The labor requirements of the cash crops grown in this region demanded a large and reliable workforce, since each had specific needs for both seasonal and general year-round upkeep and care. The plantations in other regions nearby—such as Djamanjary Sugar of Nosy Be—recruited prison labor from the south in the early 1920s.[13] In contrast, the Sambirano quickly became well known throughout the island for the availability of wage labor, and so the plantations of the Sambirano did not find it necessary to engage in an aggressive recruitment of workers from other areas of the island.[14] Unlike the Bemazava, who had (and still have) a reputation for being a fixed population, peoples from the high plateaux and the arid south left their homelands and settled in the Sambirano. For example, Betsileo—who are famous in Madagascar for their skills as rice farmers—came and settled on CNIA property as land tenants, developing the area around Antsakoamanondro, just north of Ambanja, into fertile irrigated paddy land. Antandroy, Antaimoro, and other peoples of the economically depressed south and southeast also came to work as manual laborers in the fields.

Effects on Land Tenure

Although many of the Bemazava had been alienated from their original territory through relocation, this same policy enabled them to maintain access to arable land throughout the twentieth century. In addition, numerous small villages and private family plots remained scattered throughout the Sambirano, interspersed with plantation lands. A perusal of colonial property records reveals that subsequent transactions of land involving Malagasy were uncommon during the colonial period, so that migrants were unable to acquire land when sales did occur. Instead, priority was given to members of the Bemazava royal family. This was an important trend during the colonial period, whereby the French granted royalty special privileges, assuming that if they could control the Bemazava rulers they could control their subjects. For example, the father of one of my informants was a member of the royal family and was among those royalty (ampanjaka) who were in the direct line of succession; in addition, he was a favorite among a number of French colonial officers. As a result, he was able to purchase several large plots throughout the Sambirano during his lifetime, including one in the 1930s which was nearly fifty hectares in size. Throughout the colonial period, pieces of land of this magnitude generally only went to Bemazava royalty and foreign-born planters.

To some extent, French colonial law favored all local Bemazava, and this enabled commoners as well to maintain control over valuable parcels of land in the valley, albeit smaller in size than those owned by royalty. Among those Bemazava commoners who remained landed, a bilateral rule of inheritance prevailed. Land was generally divided fairly equally among the spouse and male and female offspring when the parent (biological or classificatory) was either too old to farm or had died. For example, two of my informants (one male, the other female) owned two and four hectares of land each, where they grew primarily dry rice. Each had inherited their land from their mothers. The man was an only child whose father had died when he was very young, and previously his mother had inherited land, along with her mother and siblings, when her own father had died. My female informant could trace land inheritance among her kin through six generations. Each time someone died their land was divided fairly equally among their children (sometimes including favorite classificatory offspring) and their surviving spouse. In her kin group land was also acquired in four other ways: as gifts from royalty for performing royal service (fanompoan̂a), as previous residents of indigenous reserves, by periodically purchasing plots of two to three hectares each, or as a result of Napoleonic law, which honors the land rights of squatters who make productive use of land. These methods of land acquisition helped to offset the common trend whereby the size of inherited plots grows smaller with each generation.

Today, tera-tany continue to be favored over vahiny as a result of government reforms following Independence in 1960 and, to a lesser extent, from the sales or confiscation of large private holdings through the nationalization of large private estates that followed the 1972 Socialist Revolution. In the Sambirano, those who own land are truly at an advantage, for even plots rejected by foreign planters give high yields. Land, however, continues to become increasingly scarce, and, as the story below illustrates, it is a source of much contention among kin.

Zaloky’s Homestead

Zaloky estimates her age to be about fifty years old, although she looks as though she could be another twenty. She is Sakalava tera-tany, born and raised in an area which, in her childhood, lay on the outskirts of town; within the past twenty years, however, it has become a thriving neighborhood. She lives on a small patch of land (approximately one quarter of a hectare) which she inherited from her widowed mother. In the past she had a garden on an adjacent plot of land but now she is boxed in on all sides by new houses, several of which are concrete. She now farms a small field in her mother’s native village, which lies eighteen kilometers from town. Zaloky was married at age sixteen and she had four children. At age thirty-five her husband died; five years later she remarried (by common law) a Tsimihety vahiny named Marcel who would come each year to the Sambirano for the harvest season. He now works off and on at the enterprises. Because he is old and suffers from a bad back, however, it is difficult for him to find steady work. In 1987 he also worked as a night watchman.

The homestead on which Zaloky and Marcel live is dusty and in disarray; rather than having a neatly swept yard bordered by flowers, like most Sakalava homes, it is littered with metal scrap and old papers that get swept up by the wind and caught in the fence. Marcel sells these items when he can as a way to supplement their income; Zaloky also has two scrawny chickens that she keeps so she can sell the eggs. Their income is meager at best, and nearly every day they beg for food from their neighbors and the Lutheran church that is behind their house.

Her homestead is one that is a source of much conflict: ever since her first husband’s death her children have fought to have rights over this land. Since she married Marcel, two of her children (a son and a daughter) have filed a case in court to take it away from her. As Zaloky explains, her children believe that Marcel only married her for her land, and she states flatly that she certainly would rather give it to him than to them! Within the last year a disco has also been built next door, and the proprietor threatens them several times a week, saying he wants them to die so he can expand into their yard. He has already tried to tear down the fence, and so each day Zaloky and Marcel check to make sure it is in its proper place.

Zaloky’s problems are extreme: a tale such as this, involving children seeking to evict their mother from her land, is one most Sakalava in Ambanja would listen to in disbelief. Nevertheless, it is instructive, since it reveals the severity of tensions underlying the scarcity of land in the Sambirano. The fact that her second spouse was not tera-tany, but a migrant, brought familial conflicts to the fore. Zaloky’s story is one that threads its way invisibly through the following chapters, for she had at one time been a medium for a prestigious tromba spirit, and it was through this work that she met Marcel, who had often consulted her in times of personal crisis. The continuation of her story will appear in chapter 10, for ten years ago she converted to Lutheranism, a choice that (as the next chapter will illustrate) is an unusual one for Sakalava. As tensions with her children, and now her neighbor, have worsened, Zaloky has recently decided to give her land to the church, and the pastor has solicited the national center for funds to pay the surveyor’s and lawyer’s fees that will enable them to make a formal and legitimate claim.

| • | • | • |

Local Power and Reactions to Colonialism

Local Authority and Power

Today the power structure of the town of Ambanja is multifaceted and complex, the town serving as a center for both secular and sacred power. There are a number of institutions that operate here. First, officially recognized power lies with the state, a structure that originated during the colonial era and which continues today under the independent government of Madagascar. It is composed of a hierarchy of national, provincial, county, town, and neighborhood authorities. There are also other, more informal, power structures at work in Ambanja. The state-owned enterprises wield much control in the Sambirano, since they play an extremely important role economically, one that affects the everyday lives of local people in many ways. Even though directors are state employees, they exercise great freedom in making decisions that affect the local economic and social order of the Sambirano. For example, much of the town’s funding for celebrations, transportation, roadwork, and so forth comes from the enterprises, with donations made by the directors themselves. The patron-client relationship between the enterprises and the townspeople is so strong that a common response to an important family or personal problem is to turn to one of the directors for assistance, whose responses can be either rewarding or devastating. Likewise, religious groups—be they Islamic, Protestant, or Catholic—provide support through divine injunction and financial assistance. The Catholic church is by far the wealthiest (as is reflected by the extent of its landholdings in town), and it is also the most influential. The Catholic church also provides access to rare opportunities beyond Ambanja and outside of Madagascar, particularly through education.

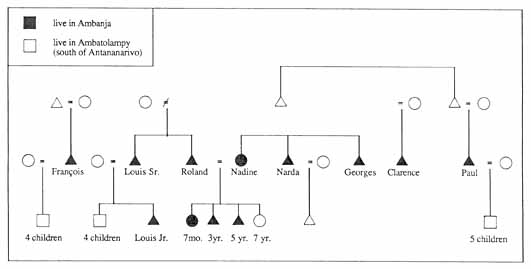

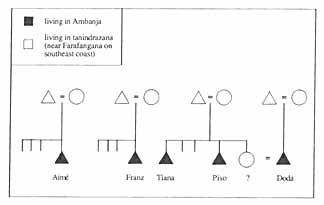

Prior to French occupation of Bemazava territory, political power and authority lay almost exclusively with the local royalty, that is, with the ruler and his or her advisers—be they living or dead. As will become clear in Part 2, by far the most important role was played by the tromba spirits and their mediums on Nosy Faly. With the arrival of the French, however, control shifted to colonial administrators and planters. This shift in the power base led to the relocation of the Bemazava ruler from the ancestral village of Ankify to the commercial center, Ambanja. This occurred during the reign of Tsiaraso II (Andriamandefitriarivo), who was the father of the present ruler, Tsiaraso III. Tsiaraso II reigned from 1945 to 1966, and from conversations with informants I assume that the move occurred early in his career (figure 2.4). Furthermore, French policies were designed deliberately to undermine the royal family’s power. The most effective effort involved recruiting royal children to be schooled at the local Catholic Mission. These children were trained to be civil servants for the colonial administration, whose loyalties and interests lay with the French and not their own people (cf. Feeley-Harnik 1991b: 137).

2.4. Rulers (Ampanjakabe) of the Bemazava-Sakalava Dynasty. Sources: Informants accounts; written Bemazava historical records; and De Foort (1907: 130).

Although royal power has diminished considerably (again, cf. Feeley-Harnik, 1991b), the present ruler (ampanjakabe) remains an important figure in the lives of the Bemazava. He is often preferred over the local court as a mediator in private disputes, and as the official living guardian of the local tanindrazan̂afa, he is the first authority one must consult prior to any further development of local land (see chapter 6). Spirit mediums also seek his blessing as well as his guidance in matters involving royal ancestors. The extent to which royalty more generally may become involved in the reassertion of royal power is exemplified in the actions of an Antakarana ruler to the north, who has become heavily involved in the revival and reinvention (Hobsbaum 1983) of royal rituals, which may draw a crowd of thousands of participants.

Local government officials honor the importance of royalty at public (state) occasions. A respect for Malagasy customs (HP/SAK: fomba-gasy; also referred to as fombandrazana/fombandrazan̂a or “customs of the ancestors”) remains strong in Madagascar. As part of malagasization, the national government has encouraged and institutionalized the observance of fomba-gasy at public events. Tromba mediums in particular have become very active, since the permission of the spirits must be sought through them, for example, prior to the naming of a local school after a past ruler or at the beginning of each season before boats of a state-owned fishery enter the waters near Nosy Faly (see chapter 6). Nevertheless, one has a sense of cooptation of living royal authority by the state, ironically illustrated by the fact that the present Bemazava ruler is Catholic and works at the county office as a tax collector.

Resistance and Revolt in the Sambirano

Bemazava reaction to the French occupation and the eventual transformation of the landscape was neither accepting nor passive. As Stoler’s work in Sumatra’s plantation belt illustrates, what may be presumed to be a peaceful occupation, settlement, and development by colonial forces may in fact be marked by acts of violence by the seemingly powerless against the powerful (Stoler 1985). At first glance, for a number of reasons it does not appear that French activities in the Sambirano were greatly hampered. First, it would have been difficult to present a united front against the French, the Bemazava being relatively few in number and scattered throughout the valley. Second, although Bemazava warriors were known to be fierce, their access to firearms was limited. Third, they regarded the French as their allies, since they had conquered an old enemy, the Merina.

Nevertheless, acts of violence against the French did occur. An incident cited frequently by the Bemazava involved a private dispute that quickly became a public—and political—one. Shortly after the French military post in Ambato was established, a group of Bemazava men were captured and imprisoned for having killed a Frenchman. The Frenchman had been living in the royal village of Ankify and was married to a Bemazava woman of royal descent. Jealous of his wife’s interactions with other men, he had confined her to the house. Since she was royalty (ampanjaka), other Bemazava regarded this as offensive and killed the husband. Captain Verdure had the prisoners beheaded in order to discourage future violence against French citizens. This episode is still remembered with great bitterness by the Bemazava. Much of their anger focuses not only on the French but also on Senegalese soldiers who were brought there by the colonial government to help maintain order. These soldiers are said to have tried to eat the prisoners’ bodies until Verdure stepped in to prevent such an outrageous act.[15]

The Sambirano became a politically charged area in 1947, a year that today is commemorated in Madagascar as a time of revolution and early nationalism. The front of resistance was located on the east coast of the island and began in March 1947. Malagasy in other areas of the island subsequently staged their own revolts against the French (see Covell 1987: 26; Rajoelina 1988; Tronchon 1974). Following the lead of revolutionaries elsewhere, inhabitants of the Sambirano behaved disrespectfully to French as they passed in the streets and the workers of some plantations went on strike. By November 1947, a small rebel group had formed in the Sambirano with a camp established in a village southwest of town, where they secretly manufactured knives and guns. Within a few months, however, the leaders were captured and imprisoned, putting an end to a potential uprising.

Resistance may also take more insidious forms, which are culturally more appropriate yet perhaps less effective against foreign invaders (Scott 1985). The Ramanenjana or “dancing mania,” which occurred in the Merina capital of Antananarivo in 1863, is perhaps the most large-scale resistance movement against foreigners involving religious forces. At this time the streets were crowded with hundreds of people possessed by the dead Queen Ranavalona. The possessed often disturbed and even attacked Europeans, many of whom were Protestant missionaries (see Davidson 1889; Sharp 1985).

Without doubt, during the colonial period Malagasy throughout the island appealed to the ancestors and other spiritual forces for assistance. In the Sambirano, it is certain that Sakalava sought to cause harm to or drive these foreigners from their homeland. They appealed to specialists such as herbalists (moasy), diviners (mpisikidy ), and tromba spirit mediums, making use of Malagasy medicine, or what Europeans referred to as magic (fanafody, fanafody-gasy). According to one informant, at the time of the 1947 revolt in the Sambirano, dead and living forces united against the colonial government; Malagasy who sympathized with the French were victims of “occult forces” (forces occultes) including tromba and other spirits, and fanafody. As will become clear in subsequent chapters, the use of fanafody continues to be a powerful way to control events in everyday life. Tromba mediums in particular play a special role in this manipulation of the spiritual realm. In addition, tromba as an institution has been a source of Sakalava pride and identity, as well as a means of Sakalava resistance to foreigners. During this century it has operated as a reminder of things past. It has also provided an idiom through which to critique contemporary experiences.

The Social Construction of Work

Throughout the twentieth century, by far the most significant form of resistance, in terms of its impact on European attitudes and policies, has been the Sakalava’s refusal to work as wage laborers. Although a requirement under the colonial regime was ten days per year of enforced (corvée) labor, ownership of land enabled many local Sakalava to avoid having to work full-time for the plantations (for a discussion of similar policies throughout the island see Thompson and Adloff 1965, chap. 23). Furthermore, many Bemazava were able to pay the mandatory head tax through cash-cropping or by selling their cattle. As a result, early in the century the plantations began to hire laborers who came from other areas of the island. To understand the logic behind Sakalava actions, it is necessary to analyze the meaning of work in their society.

Feeley-Harnik, in her discussion of slavery and royal work among the Sakalava in Analalava, states that Sakalava distinguish between two types of work: asa, or work owed to kin, and fanompoan̂a or “royal work or service that is part of their politico-religious and economic obligation to the monarchy” (Feeley-Harnik 1984: 3). In Ambanja (and elsewhere in Madagascar), asa also has other meanings: as a noun, it can mean “task” or “project,” and the verb miasa, which is often translated “to work,” is used more generally to mean “to be occupied” or “active” or “to be working on a task, a project.” For example, if a woman is doing the laundry, one says “miasaizy” (“she is working”). Beginning in the colonial era, asa took on additional meanings, as a result of the penetration of a capitalist economy and its associated labor relations. The French used asa to mean wage labor, as well as enforced, mandatory work that involved clearing roads, for example (cf. Feeley-Harnik 1991b, especially p. 349).

French concepts of work ran contrary to Sakalava ones. Since, for Sakalava, work was something that one did out of loyalty to kin and local rulers (Feeley-Harnik 1986, 1991b), requirements imposed by the French government and plantations negated local custom. From a Sakalava point of view (and certainly from a French one as well) fulfilling these work requirements was a sign of loyalty to the colonial administration. Feeley-Harnik (1984), in her discussion of slavery and royal work, argues that this action by the French was deliberately designed to undermine local royal authority and to disrupt the local sociocultural order. (For other discussions of Malagasy conceptions of work see Decary 1956; on the implementation of French colonial policy elsewhere in Africa see Crowder 1964 and Gifford and Weiskel 1974.)

In the Sambirano these efforts were only partially successful. Although royal authority has certainly diminished, many people still look to the local Bemazava king as an adviser and mediator in local disputes. It is also acknowledged that his authority is legitimated by the tromba spirits. Those who today turn to royalty (living or dead) for guidance are not only local Bemazava-Sakalava, but also many others who have become involved in tromba possession and serve as mediums for these spirits. The local government often must rely on the support of the king if it wishes to encourage participation by community members in local activities. On International Workers’ Day (May 1), for example, only the blessing of the king ensures that townspeople will help to repair the roads in town—this time as a sign of support for the present socialist state.

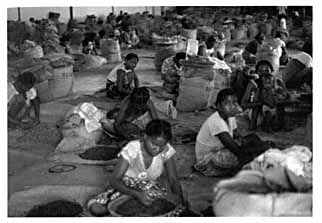

Plate 3. Women at work at a local enterprise. Women are hired to sort cocoa, coffee, and cashews. They are paid by the number of bags they fill in a day.

Sakalava resistance to work—in the form of wage labor—is often cited today by employers, who speak of them as “lazy” (kamo) or as too independent and proud to be willing to work for others. Sakalava youth express a preference for working in fields owned by kin to wage labor, be it manual or more highly trained supervisory positions. As the chapters in Part 2 will show, tromba possession also provides mediums with a means through which they may resist wage labor, particularly at the enterprises. A sentiment that many Sakalava express is that in such work there is no freedom: the hours are long, the pay is too low, and the fruits of their labor belong to someone else (see plate 3). The refusal to work was and still is a strong form of resistance to capitalist discipline. Such relations involve, first, a readjustment to clock time (Thompson 1967),[16] and, second, the displacement of reciprocal relationships by having services paid for with cash, both of which Sakalava despise. Throughout this century Sakalava have resisted engaging in such relations with non-Sakalava. In the past, these were foreigners. More recently they are Merina, who now form the majority of managers at the enterprises. This action, however, has its price: after Sakalava refused to work for foreign planters they witnessed the inundation of their territory by a variety of non-Sakalava migrants.

Notes

1. Two species of shade trees predominate here. The Malagasy names for them are montany and bonara. I have been unable to identify their scientific names.

2. See Gade (1984) for an interesting discussion of ylang-ylang fields creating a “smell-defined space” in Nosy Be.

3. This was still under construction in January 1988.

4. Because of a paucity of literature on the history of the northern Sakalava—and coastal peoples in general—much of the data acquired for this chapter have been drawn from the oral historical accounts of informants. The most valuable written sources for general background information on this region are: Baré (1980, 1982); Boucabeille (1897); Dalmond (1840); De Foort (1907); Dury (1897); and Mellis (1936); see also Feeley-Harnik (1978, 1982, 1991b), Lombard (1988), and Raison-Jourde, ed. (1983).

5. As I noted in chapter 1, throughout this study I will use the general term Sakalava to refer to the indigenous inhabitants of the Sambirano. Since this present chapter addresses their historical origins, I have taken care to refer to them by their exact name, the Bemazava (branch of the) Sakalava. I also use this term here so as to distinguish the Bemazava from the Bemihisatra-Sakalava, their neighbors who live to the south and on Nosy Be.

6. For more detailed accounts of Sakalava royal history, see, for example, Baré (1973), Feeley-Harnik (1978, 1982, 1988, 1991b), Guillain (1845), Lombard (1988), Noël (1843), Raison-Jourde (1983, especially the map on p. 44), Schlemmer (1983), and Valette (1958).

7. All Sakalava royalty will eventually have at least two names: the first is the name they use when they are alive, the second is a posthumous praise name (fitahina [Lombard: 1988]) which commemorates their great deeds. Thus, Andriantompoeniarivo means “the king who was worshiped by the multitudes” (andrian-, royal prefix; tompoeny “to honor, worship”; arivo, “thousand” or “many”). Since many royalty also become tromba spirits after they die, this second name is often referred to as the “tromba name” (ny ianarana ny tromba). Although today very few people honor the rule, in the past it was fady or taboo to utter a royal person’s living name after he or she had died. In general, I will respect this rule, except where it becomes necessary to distinguish the living person from the spirit. The significance of this rule will become clear in Part 2.

8. For analyses of the ritual and other symbolic applications of the Sakalava expression “each/both,” see Feeley-Harnik’s (1991b) ethnography of the Analalava region.

9. In the case of Millot, 80 percent of his lands were acquired through the French government, the other 20 percent from sales by private farmers.

10. The reasons for this are complex and I will not detail them here. Simply put, Millot has remained private as a result of the shrewd understanding on the part of the company’s managers of the laws and restrictions that affect private ownership and international trade in Madagascar.

11. De la Motte St. Pierre’s property has changed names and ownership several times throughout the century. By the 1920s it was referred to as the Société Agricole du Sambirano. In 1929 some lands were sold to the Compagnie Nosybéenne d’Industries Agricoles (CNIA). By the 1930s it went by the name of Compagnie de Cultures Coloniales (CCC) and then in the 1950s became the Compagnie de Cultures Cacayères (CCC). It appears to have eventually merged with CNIA, and then in 1964 all CCC holdings were divided into two farms: CNIA, based in the village of Ambohimena, and SOMIA (Société Malgache d’Industrie et d’Agriculture) in Bejofo. Regardless of these transactions, the present holdings of CNIA and SOMIA are roughly equivalent to what de la Motte St. Pierre had laid claim to at the turn of the century.

12. A hectare is equivalent to ten thousand square meters or approximately 2.47 acres.

13. Similarly, the prison in Analalava provided labor for that region as well (Feeley-Harnik 1991b: 7).

14. As Feeley-Harnik describes in her account of the Analalava region, movement and relocation are very much a part of Sakalava royal history, as each ruler seeks to establish a new residence following the death of his or her predecessor: royal death pollutes the earth, making it too “hot” (mafana) and “filthy” (maloto) for future habitation. In reference to the period of French occupation, however, she reports: “By the early twentieth century, Sakalava…were not known for moving about like Tsimihety, Merina, or Betsileo. On the contrary, French ethnographers since the turn of the century described the Sakalava as dying out in the face of more vigorous competitors for their land” (1991b: 2).

15. This remark also serves as an illustration of Malagasy attitudes toward other African peoples. The word Senegal is Malagasy slang for non-Malagasy peoples of African descent. Also, cannibalism is a theme that is reiterated by Malagasy when they seek to distinguish themselves from other African peoples of the mainland.

16. For a vivid example of the introduction of clocks in southern Africa see Comaroff and Comaroff (1991: xi).

3. National and Local Factions: The Nature of Polyculturalism in Ambanja

As a booming migrant town, Ambanja is a mélange, a mixture of peoples of diverse origins, not only from within the boundaries of this large island, but from abroad. This town is a microcosm of factions that operate on a national scale. Of these factions, ethnicity is the primary category, one that overlaps with a variety of other group orientations and allegiances. These are shaped by historically based geographical, economic, and religious differences. Such groupings or identities, when taken in total, reveal the complexity of the tensions operating in Madagascar and, in turn, in Ambanja. An individual’sability to make sense of and become established as a member of one or more groups determines his or her well-being in this community.

The complexity of categories that exist in Ambanja is extreme when compared to other areas where the population is more homogeneous. As a result, in Ambanja and the surrounding Sambirano Valley, defining what it means to be an insider or an outsider is complex. For this reason, the discussion on migration is divided into two chapters. This chapter will address the nature of social and cultural divisions that exist, first on a national scale and then in Ambanja. Chapter 4 provides case studies drawn from migrants’ lives and analyzes those factors that facilitate or inhibit their integration into local Sakalava tera-tany society.

| • | • | • |

National Factions: Regionalism and Cultural Stereotypes

Ethnic Categories

The Malagasy

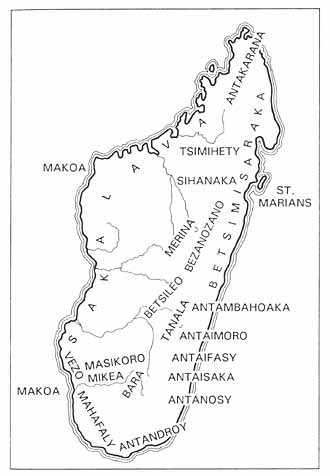

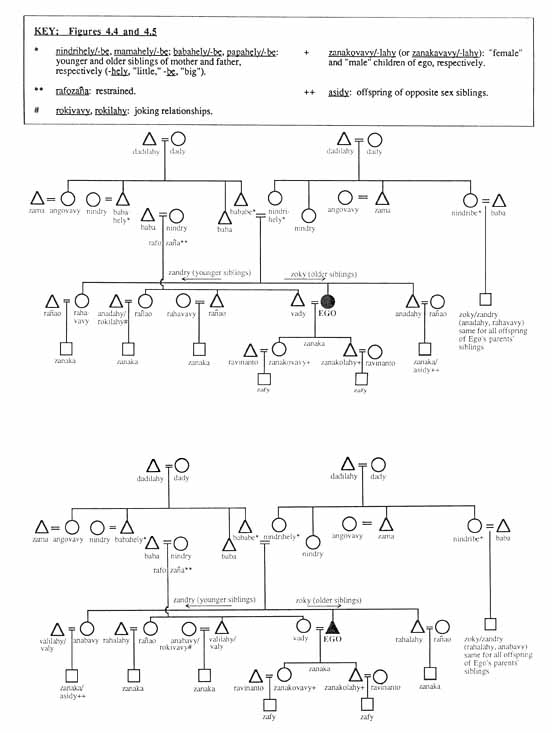

Today in Madagascar there are eighteen[1] (Covell 1987: 12) officially recognized ethnic groups (FR: ethnie,tribu; HP: foko,karazana; SAK: karazan̂a) which are relevant for census purposes (figure 3.1).

| Group Name | Population % | Group Name | Population % |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3.1. Malagasy Ethnic Groups. Sources: Covell (1987: 12), after Nelson et al. (1973), figures from the Institut National de la Statistique in Madagascar, and Thompson (1987). Reproduced by permission of Pinter Publishers, Ltd., London. All rights reserved. | |||

| Merina | 26.1 | Sihanaka | 2.4 |

| Betsimisaraka | 14.9 | Antanosy | 2.3 |

| Betsilio | 12.0 | Mahafaly | 1.6 |

| Tsimihety | 7.2 | Antaifasy | 1.2 |

| Sakalava | 5.8 | Makoa | 1.1 |

| Antandroy | 5.3 | Benzanozano | 0.8 |

| Antaisaka | 5.0 | Antakarana | 0.6 |

| Tanala | 3.8 | Antambahoaka | 0.4 |

| Antaimoro | 3.4 | Others | 1.1 |

| Bara | 3.3 | ||

The use of the term ethnic group is problematic from an anthropological point of view, since all of these groups are actually subgroups of the general category Malagasy, whose members share common cultural elements such as language and religious beliefs. In other words, the concept of ethnicity is one of perspective and scale. Outside Madagascar, Malagasy are viewed as the dominant ethnic group of the country, and Sakalava, Merina, and other peoples are considered subgroups of this larger category. From a Malagasy point of view, however, Merina, for example, are viewed as the dominant ethnic group, and other non-Malagasy peoples (Arabs, Indo-Pakistanis, Chinese, Comoreans, and Europeans) are grouped separately as “strangers” or “foreigners” (étrangers). Since this study is concerned primarily with Malagasy peoples, I will use ethnic group as the Malagasy themselves do. These ethnic divisions are significant in everyday discourse, as Malagasy use them to define themselves in relation to each other. Ethnic groups also overlap with other categories based on geographical, economic, and religious differences.

Ethnic categories have changed over time. As Covell points out, they are flexible constructs, and although they are in part a reflection of changes in the political climate of Madagascar, it would be false to conceive of them solely in these terms:

This form of identification hardly constitutes a key to Malagasy politics. The groups themselves are riddled with internal subdivisions and several are, in fact, political constructions created from small groups in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries: the Merina, Sakalava, and Betsimisaraka are the most important of these. Others, such as the Betsileo and Bara were first grouped together as administrative subdivisions of the nineteenth-century Merina empire. (1987: 12)

The French also made use of these categories. They did not begin systematically to take official censuses, with Malagasy broken down into different ethnic groups, until 1949, following the 1947 revolt. This practice was continued by the government of the Malagasy Republic after Independence (1960) up until the time of the Socialist Revolution in 1972. For approximately a decade afterward, no census information was collected (publications in general came to a halt in Madagascar at this time). In the Sambirano Valley it is only in 1985 that new efforts were made to gather census data in preparation for national elections that occurred in early 1989. On these recent censuses, the ethnic categories no longer appear, although logbooks kept of Ambanja’s neighborhood residents, for example, still make note of ethnic affiliation. In everyday discourse these categories are used by Malagasy to label one another.[2]

Today certain factors unite members of each ethnic group: a shared dialect of Malagasy; similar religious customs, most notably in regard to mortuary rituals and a strong regard for local ancestors; observation of fady or taboos; characteristic regional dress; economic activities; and affiliation with a specific geographical territory (figure 3.2). These categories and their associated characteristics are used by Sakalava as they define themselves in opposition to others. Ultimately, these differences define boundaries between insider and outsider. Among some peoples the boundaries are fluid, while among others they are very rigid.

3.2. Present Distribution of Malagasy Ethnic Groups. Sources: After Brown (1978: 16); Kottak (1986, frontispiece); and Société Malgache (1973).

Non-Malagasy Strangers (Etrangers)

In addition to Malagasy speakers, there are also a number of minority groups (see Vincent 1974: 377) that consist of non-Malagasy peoples who have settled on the island. The largest of these groups are Arabs, Chinese, Comoreans, Europeans (especially French and some Greek), Indo-Pakistanis, and peoples of mixed heritage from the neighboring islands of Réunion and Mauritius. No recent statistics are available for the size of these populations, and so it is very difficult to estimate their numbers. This is in part due to recent political events. The majority of Europeans fled the island following the Socialist Revolution in 1972. Comoreans and Indo-Pakistanis have also fled periodically, since they have been the targets of violence in the last decade or so. Out of a total estimated population of 9.9 million for the entire island (figure for 1984; Covell 1987: xiii), population estimates for each group of étrangers are: 10,000 each of the Indo-Pakistanis and Chinese; 15,000 to 20,000 Comoreans (Covell 1987; 84–85); and 12,000 French (Bunge 1983: 49; for more details see Covell 1987: 84–85; on the Chinese see also Slawecki 1971 and Tche-Hao 1967).

Malagasy Ethnic Groups: How Difference Is Perceived

A variety of factors delineates boundaries between ethnic groups. To illustrate how these operate, I will briefly discuss two such factors: physical differences and the fady or taboos. Sections that follow provide discussions on other distinguishing characteristics, such as territorial affiliation, economic specialization, and religion.

Highland and coastal peoples (and, in turn, specific ethnic groups) are distinguished from one another by dialect and phenotype, reflecting the diverse historical and cultural origins of the Malagasy. As Bloch explains:

In addition, style of dress and specific customs serve as markers of difference. Clothing styles vary as one moves from one area of the island to another. In the central and southern highlands, which have a cool, temperate climate, most Merina and Betsileo wear western-style clothes. A style that is considered to be more traditional among these people is the akanjo, a knee-length shirt made of plaid flannel which is worn by peasant men throughout the highlands. Merina women (regardless of class) are also easily recognized since they often wear a white shawl (lamba) draped over their shoulders for formal occasions. The coastal areas are humid and tropical, and all around the rim of the island men and women wear body wraps made of brightly printed cloth (called a lambahoany). Among the Sakalava this consists of the kitamby for men, which is a waist wrap worn like a sarong, and for women, a salova (salovan̂a), which is wrapped around the waist or chest, and kisaly, draped over the shoulders or head. This style of dress is very similar to that worn by Swahili of the East African coast. The far south, which is occupied by such people as the Bara, Mahafaly, and Antandroy, is an arid region. Here men often dress in shorts, a short-sleeved shirt, plastic sandals, and a straw hat, while women wear western-style dresses or lambahoany. Throughout the island different hats as well as hairstyles also serve as markers for ethnicity. For example, the name Sakalava means “[People of] the long valleys,”[3] while the Tsimihety (“Those who do not cut their hair”) were so named by the Sakalava after they refused to cut their hair in mourning as an assertion of their independence following the death of a Sakalava ruler (Société Malgache 1973: 46, 47).Madagascar has always been considered an anthropological oddity, due to the fact that although geographically it is close to Africa the language spoken throughout the island clearly belongs to the Austronesian group spoken in Southest Asia; more particularly Malagasy is linked to the languages spoken in western Indonesia. These surprising facts are also reflected in the biological and cultural affinity of the people. Although there is much controversy over the relative importance of the African and Indonesian element in the population, there is general agreement that we find the two merged together throughout the island. In some parts one side of this dual inheritance is more important; in other regions it is the other side that seems to dominate. For example, all commentators agree that among the Merina…the Southeast Asian element is particularly strongly marked. (1986: 12)

Fady (taboos) are another important aspect of Malagasy identity. They are widespread yet specific to particular peoples and regions and have been carefully catalogued in books on Malagasy folklore (see Ruud 1960 and Van Gennep 1904; see also Lambek 1992). Fady work at many different levels: all ethnic groups have their own particular ones and smaller groups, such as villages or kin groups, may observe specific fady. Individuals may have personal fady that are determined at birth by the vintana or the Malagasy cosmological zodiac system (see Huntington 1981), or which they have collected over time as a result of sickness or other experiences. Fady may consist of dietary restrictions or clothing requirements, and locations or particular days of the week may have fady associated with them. Complex constellations of fady may surround particular ritual settings or events, such as burials for commoners or royalty. They are also a key aspect of tromba possession.

Among the Sakalava, the following are important examples. Pork is fady for many, requiring that they avoid contact with pigs and their products. Nosy Faly (“Taboo Island,” faly being an older form of the word fady), is Sakalava sacred space that requires respectful behavior from all visitors. One can not enter the village of the royal tombs (mahabo/zomba) on a Tuesday, Thursday, or Saturday, and so visitors who arrive on these days camp out on the beach, waiting for a more auspicious time. In the tomb village (Mahabo) one must go barefoot, and women are prohibited from wearing a kisaly on their heads. Dogs are prohibited and must be killed if they enter. Tortoises, on the other hand, are sacred, and it is fady to harm them. Because of these and other fady associated with the village, visitors must carefully monitor their actions so as not to incur the wrath of the local royal ancestors. Non-Sakalava visitors to Nosy Faly must also conform to local, Sakalava fady. Thus, on this sacred island and elsewhere, when one is among strangers, fady serve as markers of difference. They also operate to control the actions of outsiders. Visitors are expected to respect local fady or risk harming themselves or others. For this reason, Malagasy, when they travel, generally inquire about local fady, and they are usually listed in tourist guidebooks (see, for example, Société Malgache 1973).

Geographical Territory and Ethnicity

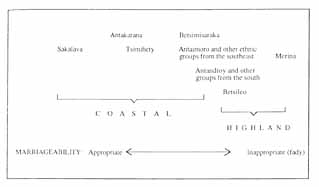

The Highlands versus the Coast

Among Malagasy, distinctions are made in reference to geographical areas and their corresponding ethnic groups, which in turn are relevant to the development of political power in Madagascar. There are, first, the peoples of the high plateaux. The most important group here is the Merina. The Betsileo, who live to the south of the Merina, occupy an ambiguous position in the minds of other Malagasy, since they are of the plateaux but are non-Merina people. I know of no general term in common usage that is applied collectively to Merina and Betsileo. Instead, more specific ethnic labels are used. Contrasted to these two highland groups are the côtiers (“peoples of the coast”), a term coined during the colonial era by the French to label all other Malagasy groups, many of whom Covell (1987: 13) points out live nowhere near the coast. The term côtiers is used most frequently by highland peoples and carries somewhat derogatory connotations.

These two general geographical categories have evolved out of politically defined divisions as a result of Merina expansion and subsequent French occupation of the island. During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the Merina conquered much of the island and established a powerful kingdom. By the early 1900s Merina royalty in Antananarivo established an alliance with the British against the French, but this alliance ended when the French conquered the island. Throughout the twentieth century the distinction between Merina and all other peoples has remained significant. With Independence, President Tsiranana (who himself was from the coast) and his party members “tried to mobilize support by portraying themselves as defenders against ‘Merina domination’ ” (Covell 1987: 13). Today, this tension persists. As Covell states, “The conflict cannot be reduced either to ethnic or class competition, but has elements of both” (1987: 13; she in turn cites Tronchon 1975).

Relations between members of these two major geographical groups are characterized by mistrust and racist attitudes. African versus Austronesian origins are a subject of important debate in Madagascar. Merina and Betsileo claim to be the most “Polynesian” of the Malagasy (see Bloch 1971: 1–5) and look disdainfully on coastal peoples, whom they often refer to as being “more African.” These comments are made most often in reference to skin color and hair texture. For example, the term Makoa (which often appears on censuses as an ethnic category, see figures 3.1, 3.2, 3.3) is used as a descriptive (and somewhat derogatory) term for people who have dark skin and kinky hair. Makoa were originally brought to Madagascar as slaves from an area in the interior of Africa that is now part of Mozambique (see Lombard 1988: 88 and Smith 1963 on the “Makua,” especially pp. 257 and 273). Highlanders in general view côtiers as backward and uneducated. Coastal peoples, in turn, express resentment of Merina who were once favored by the French and who form the majority of the population in the capital city. Merina continue to dominate the national political arena and maintain access to the best education, health care, and other services and facilities, and they fill many of the country’s civil service jobs. (For a discussion of these trends after Independence, especially in reference to education, see LaPierre 1966.) Ideas shared by members of each of these groups toward one another also include notions of uncleanliness; concepts of physical beauty, especially in regard to skin color (“white/black”: HP: fotsy/mainty; SAK: fotsy/joby); and a reluctance to intermarry (cf. Bloch 1971: 1–5, 198–201; J. Ramamonjisoa 1984).

The Tanindrazana or Ancestral Land

The most important concept used to define personal and group identity is that of the ancestral land (HP: tanindrazana; SAK: tanindrazan̂a). This may not necessarily be the locality where one lives or even grew up; it is where one’s ancestors are located and, ultimately, where one will be entombed. For all Malagasy, identity is intrinsically linked to the ancestral land. Although it is considered rude to ask what one’s ethnicity is, asking the question “where is your ancestral land” (HP: “aiza ny tanindrazanao?”) will generally provide the same information (see Bloch 1968 and 1971, especially chapter 4).

Even when Malagasy migrate to other parts of Madagascar, the notion of the ancestral land continues to tie them to a particular locale. It is not simply the geographical space, but the ancestors themselves that serve as the locus of identity and that define an individual’s point of origin. As a result, as one moves about the island, one continues to have a strong sense of ethnic identity that is geographically defined. As Keenan states of the Vakinankaratra (a group that is culturally considered to be Merina), “The worst fear of a villager is to travel far from the tanindrazana and fall sick and, perhaps, die alone” (Keenan 1974). The same may be said for the majority of Malagasy, regardless of origin.[4] Migrants and their children, who are born far from their ancestral land, may continue to invest money in a family tomb that is hundreds of miles away, so that they can be placed there when they are dead.

Economic Specialization

Another system of ranking and categorization is based on forms of economic specialization that, in turn, correspond to ethnic and geographical categories. In a country where, for the majority of peoples, the staple is rice (see Linton 1927), highland peoples pride themselves on their talents as paddy rice farmers. The abilities of Betsileo farmers are a source of great national pride: their paddies are located in the valleys and tiered on the steep hillsides of the temperate regions of the southern plateaux. Coastal peoples of the east, west, and north practice swidden agriculture, where rice is, once again, a major crop (see Le Bourdiec et al. 1969: map no. 51).

The peoples of the arid south (for example the Antandroy, Bara, and Mahafaly) are pastoralists who raise cattle and goats. Although some grow rice, manioc is an important staple. Among many Malagasy—coastal and highland alike—pastoralists are regarded as being “simple,” “primitive,” and “African,” and are said to speak dialects that are unintelligible by the vast majority of Malagasy. Pastoralists are feared by others who say that they are thieves (mpangalatra). This comment is made in reference to (and is a result of a misunderstanding of) the dahalo, or cattle raiders, since among these groups cattle raiding is an important social institution for young men. Antandroy and other pastoralists are taller than many Malagasy and the men often carry long staffs with large blades mounted on one end. As a result, other Malagasy are wary of them.

Conditions are severe in the south, made worse by a drought that has extended throughout the past decade. This has forced a large proportion of men to spend their lives as migrants, working in different parts of the island and sending remittances home (usually by registered mail) to their spouses and other kin, where much of the cash is invested in animals.[5] These migrants are drawn to the major urban centers of other regions where they are hired as night watchmen and as cowherds. They are preferred by employers because they are willing to brave the elements and sleep outdoors, even during the cold, wet winters so characteristic of the highlands (for detailed discussions of southern pastoralists see Decary 1933; Faublée 1954; Frère 1958; Huntington 1973).

Religious Affiliation

Religions of foreign origin—Islam, Catholicism, and Protestantism—provide another means for distinguishing Malagasy from one another. They define divisions that are both ethnic and geographical. Estimates for religious affliation for the entire island in 1982 are as follows: 57 percent adhere to traditional (or what I will refer to as “indigenous”) beliefs (fomba-gasy) and 40 percent are Christian, with equal representation of Roman Catholics and Protestants (Bunge 1983: 62). I assume that the remaining 3 percent is mostly Muslim, but also includes Indian Hindus.

Islam is strongest in the north and west. In contrast to other Malagasy, many Sakalava and Antakarana are faithful to Islam, their conversion having occurred in response to their efforts to find allies against Europeans in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. In addition, Arabs, the majority of Comoreans, and many Indo-Pakistanis are Muslim (see Delval 1967, 1987; Dez 1967; Gueunier and Fanony 1980; Vérin 1967).

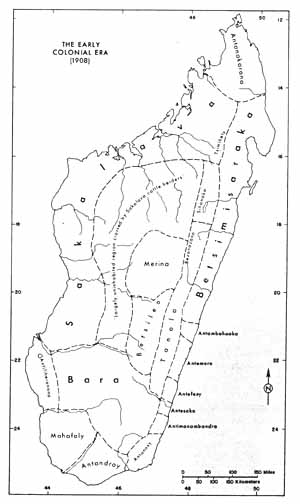

3.3 A and B. Distribution (and Migration) of Malagasy during the Twentieth Century. Source: Originally published in the Department of the Army Publication DA Pam 550-154, Area Handbook for Indian Ocean: Five Island Countries. Frederica M. Bunge, ed., 1983.

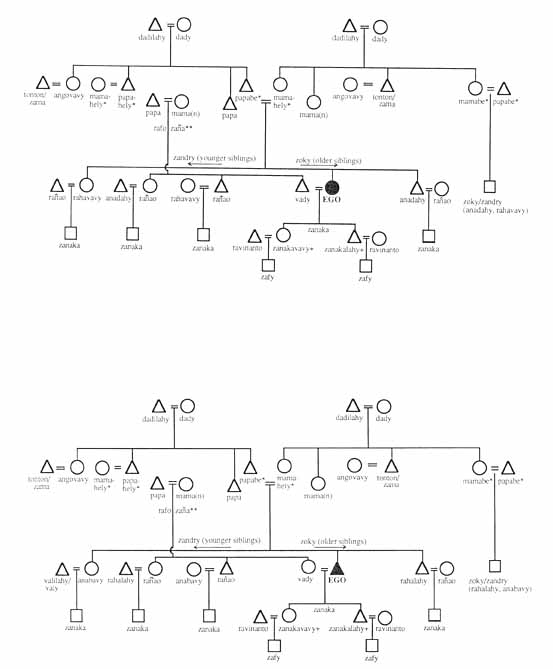

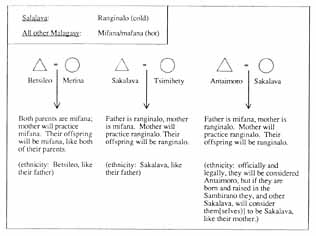

3.3 A and B. (continued)