Similarities and Differences between the Two Species

The close relationship between the two species is at once obvious to the casual observer from the similarity in size, appearance, and movements. Behavior of the two species is, on the whole, remarkably similar on land and at sea. For example, the social organization of males competing for access to females during the breeding season is similar. We describe these similarities in more detail in later sections.

Laws (1956a ) described the behavior of a small population of southern elephant seals in the South Orkney Islands, breeding on sea ice in spring and present under fast ice, in which they kept open breathing holes, in early winter. Similar behavior occurs in the South Shetland Islands, and elephant seals have been seen hauled out on pack ice (R. M. Laws, unpubl. observ.). This is in extreme contrast to some subtropical breeding locations of the northern species, for example, desert islands on the west

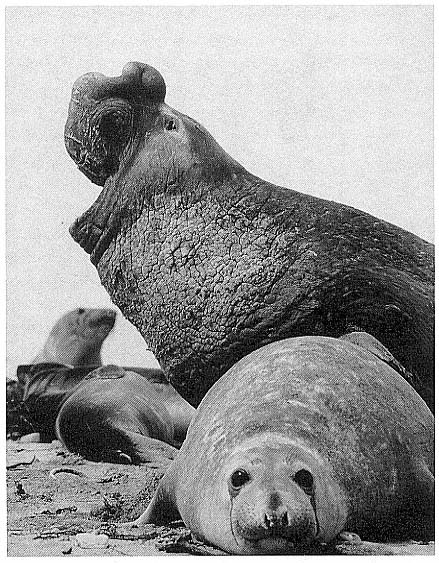

Fig. 1.1

A northern elephant seal bull bellows a threat vocalization to a competitor.

An adult female is in the foreground, and others are in the background.

Photograph by Franz Lanting.

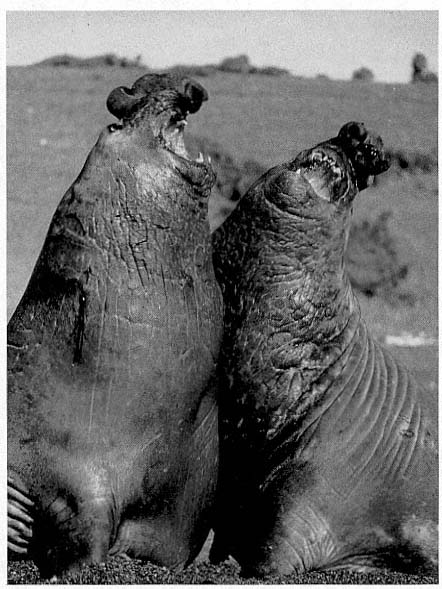

Fig. 1.2

Two southern elephant seal bulls fighting at Península Valdez, Argentina.

Photograph by Burney J. Le Boeuf.

coast of Baja California, Mexico. The dive depths and dive durations during transit and foraging are remarkably similar despite occurring in disparate parts of the ocean (Le Boeuf et al. 1988; Le Boeuf, this volume; Stewart and DeLong 1991; Stewart and DeLong, this volume; Hindell 1990; Fedak et al., this volume).

Differences between the species have not been subjected to special study; we describe the most obvious. The southern male is longer and heavier than its northern counterpart. Southern bulls in harems weigh 1,500 to 3,000 kg, with maximum weights reaching 3,700 kg (Ling and Bryden 1981). The largest northern males weigh 2,300 kg (Deutsch, Haley, and Le Boeuf 1990). Females of the two species do not appear to differ significantly in mass. Southern females range widely in mass from 350 to 800 kg shortly after giving birth, with most of them in the range 400 to 600 kg (Fedak et al., this volume). Northern females have a postpartum mass ranging from 360 to 710 kg (Deutsch et al., this volume). The mean mass of northern pups, however, may exceed that of southern pups at weaning, 131 kg versus 121 kg (Le Boeuf, Condit, and Reiter 1989; Deutsch et al., this volume; Fedak et al., this volume), perhaps owing to a difference in suckling duration (Le Boeuf, Whiting, and Gantt 1972; Laws 1953b ; McCann 1980). However, at South Georgia, mean male weaning mass in four years ranged from 118.7 to 137.2 kg (SCAR 1991), and more southerly populations of M. leonina have higher weaning weights; for example, R. M. Laws (1953b ) found weaning weights of about 200 kg at Signy Island in 1948–1949, and H. Burton (pers. comm.) reports high weaning weights at King George Island.

Laws (1953b ) and R. Carrick, S. E. Csordas, and S. E. Ingham (1962) report southern bulls measuring 6.2 m, and others refer to males of 7.62 to 9.14 m; the early records, however, probably included hind flippers and are not comparable (see Scheffer 1958). C. M. Scammon (1874) reports a northern male that measured 6.71 m, but the longest northern bull measured in recent times was 5.03 m long (B. Le Boeuf, unpubl. data). The average lengths of males seem to be less disparate across species; Laws (1960) estimated 4.72 m for southern males, and mean estimates for northern males range from 4.33 m (Deutsch et al., this volume) to 4.48 m (Clinton, this volume).

Some morphological differences between the species beg explanation. For example, the southern elephant seal can bend its body backward into a Ushape over a much greater angle than the northern elephant seal. Perhaps because of this difference, southern males also seem to be able to rear up higher during fighting than northern males. Paradoxically, despite greater sexual dimorphism in skull characteristics in southern elephant seals, the fleshy exterior of the northern species is more sexually dimorphic. The proboscis of the northern male is larger and the integumentary neck and

chest shield are more highly developed than these features in the southern male (Murphy 1914; Laws 1953b ).

Developmental differences in early life deserve further study. Southern pups are weaned at 22 to 23 days of age (Laws 1953b ; McCann 1980; Campagna, Lewis, and Baldi 1993); northern pups are weaned at 24 to 28 days, nursing duration increasing with the age of the mother (Reiter, Panken, and Le Boeuf 1981). Some southern elephant seal pups begin molting while still suckling; a small percentage molt in utero (Laws 1953b , 1956a ; Carrick et al. 1962; Le Boeuf and Petrinovich 1974). For pups at Signy Island, Laws (1953b ) reports that the molt lasts about 24 days and is completed by 30 to 38 days of age. The molt in northern elephant seal pups is equally long but does not begin until after weaning, at about 28 days of age; the process begins slightly later in males than in females (Reiter, Stinson, and Le Boeuf 1978).

In the southern elephant seal, weaned pups fast for an average of 37 days, and the duration of the postweaning fast increases linearly with increasing weight at weaning. Pups continue to fast until they reach a lower weight threshold of about 70% of weaning weight (Wilkinson and Bester 1990). The duration of the fast in the Northern Hemisphere varies with the date of weaning. Pups weaned early fast for a mean of 73.5 ± 7.6 days; pups weaned late in the season fast for a mean of 55.6 ± 13.2 days (Reiter, Stinson, and Le Boeuf 1978). As in the south, the duration of the fast is positively correlated with weaning mass, and at departure from the rookery, pups have lost an average of 25 to 30% of their weaning weight. Some pups of both species remain near the rookery for up to 2 to 2 1/2 months before going to sea for the first time (Reiter, Stinson, and Le Boeuf 1978; Condy 1979).

The threat vocalizations of males are quite distinct, evidently a divergence that has come about with geographic separation (Le Boeuf and Petrinovich 1974). The threat call of northern males is composed of 3 to 20 discrete expulsive, low-frequency bursts that are emitted at a relatively constant rate, with some individuals adding a longer embellishment to the beginning or end of the call. The mean duration of the call is 6.8 ± 2.5 seconds. In contrast, the threat vocalizations of southern males are more than twice as long (mean = 19.1 ± 8.3 seconds) and are composed of long roars that vary in pitch and loudness, the result of a sound being produced during inspiration as well as during expiration.

The near-annihilation of the northern elephant seal population by sealers in the last century, compared to the less destructive sealing efforts in the larger and more widely distributed elephant seal populations in the Southern Hemisphere, has apparently resulted in differences in genetic variation. The extreme population bottleneck experienced by the northern species—a reduction to less than 100 individuals breeding on only one

island in the late 1880s—is interpreted as being responsible for lack of allozyme diversity and reduced DNA sequence diversity in two mtDNA regions, relative to southern elephant seals (Bonnell and Selander 1974; Hoelzel et al. 1993).