Summer Fun

Following the solemnity of Uncle Tom's Cabin , most Edison productions taken during the summer months involved elements of play. Both before and behind the camera, the spirit of Coney Island frequently prevailed.[39]Little Lillian, Toe Danseuse brought "the youngest premiere danseuse in the world" before the camera and made skillful use of stop-action photography to combine four separate dances into one continuous "shot," with "her beautiful costume changing mysteriously after each dance."[40]Subbubs Surprises the Burglar , the first of several comedies made in rapid succession, was shot on July 16th. Featuring a popular cartoon character, this single-shot film otherwise imitated Biograph's The Burglar-Proof Bed (shot June 27, 1900). When a burglar enters Subhubs' bedroom, "The man awakes and pulls a lever, closing himself up in the folding bed, the bottom of which is iron-clad, with guns and portholes. The burglar is dumbfounded, and cannot move. Subhubs turns his battery loose, blowing the burglar to pieces. He then raises an American flag on a staff on top of the bed as a signal of victory. The bed opens up again and Subhubs goes to sleep."[41] In Street Car Chivalry , an attractive young lady is offered a seat by every man in the trolley. A stout woman with an arm full of bundles, however, is ignored until she loses her balance and collapses on top of a "dude." The narrow limits of male gentility are spoofed, and the different ways each woman claims a seat provide comic repetition. The film was sufficiently popular for Lubin to remake it that fall.[42]

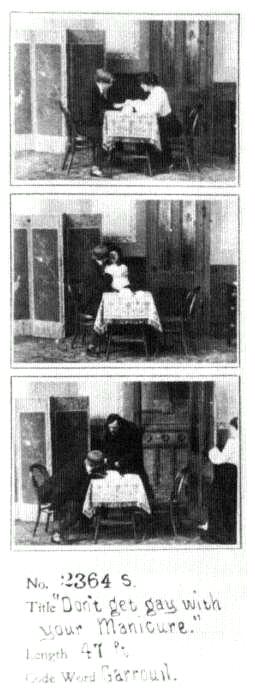

The Gay Shoe Clerk , a brief comedy shot on July 23d, was inspired by at least two films: either Biograph's Don't Get Gay with Your Manicure or No Liberties, Please[43] (shot July 10, 1902) and G. A. Smith's As Seen Through a Telescope , which Edison distributed as The Professor and His Field Glass :

NO LIBERTIES, PLEASE.

A young man in a manicure parlor attempts to kiss the pretty attendant but has his ears soundly boxed for his trouble.[44]

THE PROFESSOR AND HIS FIELD GLASS.

An old gentleman is shown on a village street, looking for something through a field glass. Suddenly, he levels the glass on a young couple coming up the road. The girl's shoe string came loose, and her companion volunteers to tie it. Here the scene changes, showing how it looks through the old man's glass. A very pretty ankle at short range. Scene changes back again and shows the old fellow tickled to death over the sight. The couple, who, by the way, caught "Peeping Tom," come toward him, and as the young man passes behind him, he knocks off his hat and kicks the stool on which he is sitting, from under him, making the old chap present a rather ludicrous appearance, as he sits in the street. Length 65 feet.[45]

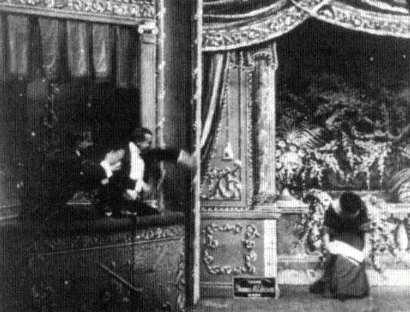

THE GAY SHOE-CLERK.

Scene shows interior of shoe-store. Young lady and chaperone enter. While a fresh young clerk is trying a pair of high-heeled slippers on the young lady, the chaperone seats herself and gets interested in a paper. The scene changes to a very close view, showing only the lady's foot and the clerk's hands tying the slipper. As her dress is slightly raised, showing a shapely ankle, the clerk's hands become very nervous, making it difficult for him to tie the slipper. The picture changes back to former scene. The clerk makes rapid progress with his fair customer, and while he is in the act of kissing her the chaperone looks up from her paper, and proceeds to beat the clerk with an umbrella. He falls backward off the stool. Then she takes the young lady by the arm, and leads her from the store. Length 75 feet.[46]

Porter's film inverts one gender position in the Biograph narrative (in which the manicurist's lover-husband boxes the man's ears). Likewise, it dispenses with Smith's matte and explicit point-of-view motivation but keeps the "very close view" of the woman's ankle. It is the man behind the camera (and presumably the male viewer) instead of the man behind the telescope whose attention is focused on the woman's ankle, motivating the cut to a closer view. Such simple shifts and recombinations suggest the variations that frequently characterized "originality" in this period.

The Gay Shoe Clerk valorizes the spectator's position in a manner that recalls What Demoralized the Barbershop (1897). True, the young man not only sees but touches and even kisses the young lady, but his transgression is promptly greeted by a bash on the head from the chaperone. Meanwhile, the male spectator enjoys the woman's ankle and the shoe clerk's chastisement. In fact, both pictures suggest that cinema, by removing the spectator's physical presence from the scene, allows the (male) viewer to take pleasure in what is otherwise forbidden. The close view of the young lady's ankle is shown against a plain background to further focus the viewer's attention, suggesting the subjective nature of the shot and abstracting it from the scene. Not only does this second shot have a different background, but the female customer probably had a stand-in. Her dress, at least, is different: the far shot does not reveal the white petticoats, which are prominently displayed in the closer view. Porter and other

The Gay Shoe Clerk. The cut from a very close view back to establishing shot.

early filmmakers obviously anticipated the editorial principles of the artificial woman articulated by Lev Kuleshov.[47] The ankle is also isolated in an abstracted space. While Porter seems to have been concerned with matching action, the cut did not involve a seamless "move in" through a spatially continuous world but functioned within a syncretic representational system.[48]

Playfulness was plentiful at the Edison studio. Thinking up skits and pulling them off was fun even if work weeks were long. One can imagine Abadie's leg—or that of some other assistant—filling the young lady's stocking in The Gay Shoe Clerk . Tasks were manageable and varied. The integration of work and play was particularly evident during August, when the cameramen chose activities that took them to resort areas and the seashore. Informal supervision and the quotidian nature of many films enabled these employees to sneak away from the hot city and relax.

On several occasions, Edison personnel took their cameras to Coney Island, where they produced actualities such as Shooting the Rapids at Luna Park and Rattan Slide and General View of Luna Park .[49] There, Porter made the "headliner" copyrighted as Rube and Mandy at Coney Island , but listed in Edison's catalog under a slightly different title:

RUBE AND MANDY'S VISIT TO CONEY ISLAND.

The first scene shows this country couple entering Steeplechase Park. They proceed to amuse themselves on the steeplechase, rope bridge, riding the bulls and the "Down and Out." The scene then changes to a panorama of Luna Park, and we find Rube and Mandy doing stunts on the rattan slide, riding on the miniature railway, shooting the chutes, riding the boats in the old mill, and visiting Professor Wormwood's Monkey theatre. They next appear on the Bowery, where we find them with the fortune tellers, striking the punching machine and winding up with the frankfurter man. The climax shows a bust view of Rube and Mandy eating frankfurters. Interesting not only for its humorous features, but also for its excellent views of Coney Island and Luna Park. Length 725 feet.[50]

Rube and Mandy at Coney Island can be compared to exhibitor-constructed programs of the period that combined travel views or scenics with short comedies—a programming idea suggested by William Selig. One can imagine a program on Coney Island consisting of Shooting the Rapids at Luna Park and similar films, but laced with studio comics for variety.[51] Working within such a syncretic framework, Porter integrated comedy and scenery, maintaining a consistent tone from one shot to the next even as he perpetuated this dichotomy within the individual shots.

In Rube and Mandy at Coney Island , two country bumpkins experience the marvels of New York's famous amusement park. While the vaudeville actors did their bits in stage costume with exaggerated gestures, Porter treated Coney Island for its scenic value with a highly mobile camera (five shots contain significant camera movement) still associated with actuality material. In several

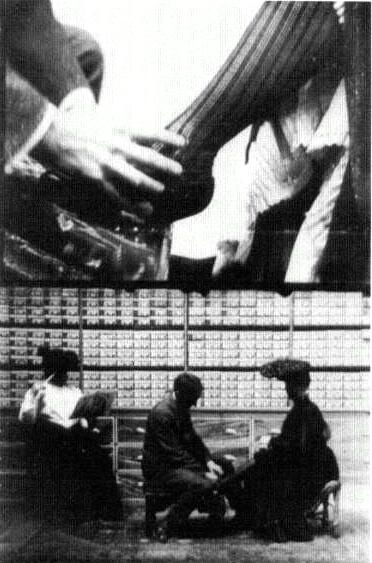

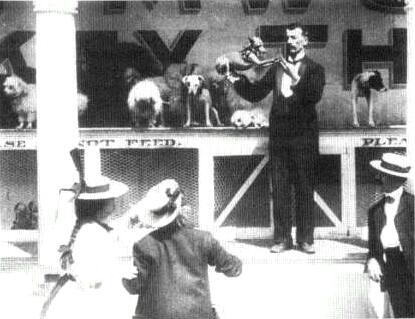

We see Prof. Wormwood and his Dog and Monkey Theater over Rube

and Mandy's shoulders in Rube and Mandy at Coney Island.

scenes the performers' improvisations forced Porter to accommodate the unexpected by following the action with his camera. In another scene, the actors' movements about the amusement park enabled the camera to photograph a "circular panorama." The performers are often subservient to a scenic impulse, not only with the panorama but at Professor Wormwood's Dog and Monkey Theater, where the film viewer looks over the actors' shoulders to see the animals perform. The couple mediates the audience's experience of the amusement park and ties together a series of potentially discrete views as they move from one ride to the next. At other moments, Coney Island serves as a setting for the comedians' business. The scenes are arranged through an association of analogous situations: Rube and Mandy's arrival in an absurd carriage is followed by rides on wooden horses and a cow; "Shooting the Chutes" is followed by a ride in a love boat. Although the film has little narrative development, it achieves a degree of closure, opening with the couple's arrival and ending with an apotheosis-like "bust view" of the two eating a hot dog against a black background. This final scene repeats the preceding one while abstracting it from the Coney Island setting and reducing it to a "facial expression" shot.

Porter spent mid August in the popular seaside resort of Atlantic City, mak-

ing at least one film during his working vacation. Seashore Frolics , staged using cooperative vacationers, ends with a persistent still photographer (Porter's assistant?) being dumped into the ocean by good-natured bathers. The cameraman closed his summer season of filming at the New York Caledonian Club's 47th annual festival of sports on Labor Day.

That August, A. C. Abadie was at Coney Island (Orphans in the Surf and Baby Class at Lunch ), then retreated to Wilmington, where he filmed outdoor scenes for N. Dushane Cloward. Cloward, a traveling exhibitor who played churches and noncommercial venues during the theatrical season, opened a motion picture show in Brandywine Springs Park for the summer of 1903.[52] He arranged with the Edison Company to take local views that would attract patrons to his theater. Cloward had Abadie photograph a baby review and a Maypole dance on August 21st.[53] Together they organized the filming of Turning the Tables and Tub Race at the local swimming hole. In the former, a policeman tries to chase a group of boys out of a forbidden swimming hole, but finds himself pushed into the water instead. The naughty boys break the law; but the law, rather than the boys, has to pay.

Cameraman J. B. Smith, although principally confined to the Orange laboratory, where he remained in charge of print production, spent part of August photographing the America's Cup races between the Reliance and Sir Thomas Lipton's Shamrock III . This news event, however, was not given the amount of attention it had received two years earlier. Only three films were offered for sale: two covered the start and finish of the first race on August 22d. The third film, taken midway through the second race, was not considered worth copyrighting. The films were offered as individual topicals rather than a complete series worthy of headliner status.

The Porter-Abadie-Smith trio continued to be the responsible photographers during the fall. After Labor Day, Porter returned to his New York base, where he filmed Eastside Urchins Bathing in a Fountain and New York City Public Bath as part of his continuing documentation of the city's ghetto life. In a sweeping panorama, the 150-foot Tompkins Square Play Grounds documents a supervised playground with basketball and boys forming a human pyramid for the camera. Porter followed his Lower Eastside shoots with various short com-edies. Two Chappies in a Box is set in a vaudeville theater, where two male spectators respond to a female performer on the stage. For today's viewer, the humor comes from a simple psychoanalytic reading. A phallic wine bottle stands between the two men on the railing of their box, and they become so excited over the woman's singing that they spill the contents and ruin the draperies. For this offense they are quickly expelled. As with many of these short comedies, an obscene joke lurks just below the surface of a film that seems to be teaching a moral lesson—that rowdy behavior will not be tolerated. Between such minor comedies, Porter filmed The Physical Culture Girl , a vaudeville-type turn that

Two Chappies in a Box.

featured the recent winner of the Physical Culture Show at Madison Square Garden. Two months earlier, Biograph had made a similar subject with the same title. Porter's Heavenly Twins at Lunch and Heavenly Twins at Odds , of baby twins, appealed to Americans' love for small children (the New York Journal , for instance, consistently ran pictures of babies, playing to its readers' sentiments).

Smith spent most of the fall working as a foreman at the West Orange film plant, while Abadie traveled along the East coast taking films of floods, fire ruins, parades, and the Princeton-Yale football game. Like Porter, they were expected to perform multiple tasks. Abadie, in particular, functioned as a roving cameraman sent on special assignment (i.e., the cameraman system). Many of these short Edison films, particularly the topicals, were done in a perfunctory fashion, perhaps because similar subject matter had been shot so frequently. After seeing films of the Galveston disaster in 1900, audiences might be expected to find Flood Scene in Paterson, N.J ., photographed by Abadie in mid October, somewhat anticlimactic. The law of diminishing returns seemed to operate and Markgraf, like other American film executives, failed to mobilize his cameramen to mount the elaborate and timely coverage that might have kept alive White's

vision of a visual newspaper. Interest was shifting to the cinema's capacity as a storytelling form. This was particularly apparent at Biograph.

In March 1903, after losing the Keith theaters as an exhibition outlet, the Biograph Company reassessed its business strategies and placed new emphasis on fictional narratives. By June, Biograph had opened an indoor film studio with electric lighting at its newly acquired offices on Fourteenth Street.[54] If the Edison Company's glass-enclosed studio had had advantages over Biograph's old rooftop facility at 841 Broadway, the competitive edge returned to Biograph, since filming was no longer affected by weather and winter hours. In the months immediately following the studio's completion, Biograph cameramen shot many multishot fictional subjects. Most were not offered immediately for sale but used as exclusive headliners for Biograph's revived exhibition service. Biograph's resurgence in production and its commitment to a 35mm format revived the company's fortunes. By August, Biograph had regained its position on the Keith circuit and was again competing seriously with Edison.

The move toward story films had accelerated by the latter half of 1903. Lubin made Ten Nights in a Bar-Room (700 feet) in October.[55] Although fairy-tale films like Méliès' Fairyland and Hepworth's Alice in Wonderland continued to be popular, English story films depicting crimes and violence began to appear and found receptive audiences. Sheffield Photo's A Daring Daylight Burglary , British Gaumont/Walter Haggar's Desperate Poaching Affray and R. W. Paul's Trailed by Bloodhounds were duped and sold by Edison, Biograph, and Lubin between June and October 1903.[56] Such films provided inspiration and competitive pressures that help to explain the production of Porter's most famous subject, The Great Train Robbery .