Improvised Song

In addition to vernacular polyphony, high and low, the academy's music included unwritten song, the sung (and probably at least partly improvisatory) recitations of poetry that formed a continuous part of the indigenous Italian culture so eloquently described by Nino Pirrotta.[56] Castiglione's Cortegiano provides evidence that both solo song and written part-song were favored by aristocratic amateurs, and Willaert's transcriptions of Verdelot's madrigals for lute and voice could well have been done by Polissena Pecorina or less virtuosic counterparts.[57] Accordingly,

[55] Varoter continues: "I have made so bold to sing Your Excellency's virtues in new melodies and to send them with other canzoni of mine to Your Excellency" (si come quella, che havendo il petto e le sue orecchie piene di gravi e delicate armonie, satia con altrimenti che di regie vivande, voglia descender a grossi e naturali cibi: Liquali io di fiori e frutti rusticani gli ho preparati . . . ho havuto ardimento cantar per modi novi le vostre virtuti, e quelle insieme con altre mie Canzoni mandare alla E.V.). The author's real name was Alvise Castellino. The passage is quoted and translated in Einstein, The Italian Madrigal 1:379.

[56] See various essays in Music and Culture in Italy from the Middle Ages to the Baroque: A Collection of Essays (Cambridge, Mass., 1984), especially "The Oral and Written Traditions of Music," pp. 72-79, and "Ricercare and Variations on O rosa bella," pp. 145-58. See also James Haar's essay "Improvvisatori and Their Relationship to Sixteenth-Century Music," in Essays on Italian Poetry and Music in the Renaissance, 1350-1600 (Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1986), pp. 76-99, and William F. Prizer's "The Frottola and the Unwritten Tradition," Studi musicali 15 (1986): 3-37.

[57] On types of music making in Castiglione's milieu see Baldassarre Castiglione, Il libro del cortegiano, ed. Ettore Bonora, 2d ed. (Milan, 1976), Book 2, Chap. 13, and James Haar "The Courtier as Musician: Castiglione's View of the Science and Art of Music," in Castiglione: The Ideal and the Real in Renaissance Culture, ed. Robert W. Hanning and David Rosand (New Haven, 1983), pp. 171-76. Willaert's transcriptions of Verdelot appeared in Intavolatura de li madrigali di Verdelotto de cantare et sonare nel lauto, 1536, Renaissance Music Prints, vol. 3, ed. Bernard Thomas (London, 1980), facs. ed. Archivum Musicum, Collana di testi rari, no. 36 (Florence, 1980). See Haar's comments on the latter in "Notes on the Dialogo della musica," p. 206, and evidence in Doni, Dialogo della musica, p. 315.

references to solo singing recur often in the Venier literature — always in conjunction with women, who, until later in the century, had no other apparent place within the academy's ranks.[58]

Several female singers who come to us through encomiastic literature had connections with Venier. In later years a series of letters by the renowned courtesanpoet Veronica Franco, printed in her Lettere familiari of 1580, establish Venier as her mentor, and two of them contain suggestive references to music making at home. The ninth one, addressed anonymously like nearly all her letters, invites friends to visit for an occasion in which she will make music at home (an "occasione in ch'io faccio la musica"). She asks to borrow a "stromento da penna," either a kind of harpsichord — probably the more portable spinet — or possibly a lute or guitar.[59] Another (no. 45) tells a friend that on the following day there will be "musica per tempo" at her house and that before the start of this "suono musicale" she hopes to take delight in his "dolcissima armonia de' soavi ragionamenti."[60] Since music was not at the top of Franco's accomplishments, these letters may have provided little more than formulas for epistolary exchange that could be adapted for use by others. Yet her allusions nonetheless point to situations in which music served as social adornment. At issue is not whether Franco herself could really sing and play, or do so well enough for Venier's salon, but rather how her claims match the more generalized expectations of courtly ladies and well-graced cortigiane oneste.[61]

Other women praised by Venier were accomplished singers who provided their own accompaniments. To one of them he wrote:

Con varie voci or questa, or quella corda With various words, now this, now that string

Tocca da bella man sul cavo legno Does the lovely hand touch on the hollow wood,

Mirabilmente il canto si al suon accorda. Miraculously tuning her song to its sound.

(no. 68, vv. 9-11)

[58] Apropos, a passage from Parabosco's Lettere amorose to a woman turns on the conceit that his love and hers issue from a concordant harmony: each of them might play and sing in separate rooms in perfect harmony, their thought in perfect agreement, so perfectly are they tuned to the same (Neoplatonic) music. The air they play is none other than the treble-bass formula called "Ruggiero" after the tradition of reciting stanzas from Ariosto's Orlando furioso in solo song; she is compared to Bradamante, he to Ruggiero (I quattro libri delle lettere amorose, ed. Thomaso Porcacchi [Venice, 1561], fols. 107-8).

[59] The term "stromento da [or'di'] penna" generally means simply plucked keyboard instrument, as, for example, in the description of the Florentine intermedi of 1518, in Lorenzo Strozzi, Le vite degli uomini illustri della casa Strozzi, ed. Pietro Stromboli (Florence, 1892), p. xiii; reported in Howard Mayer Brown, Sixteenth-Century Instrumentation: The Music for the Florentine Intermedi, Musicological Studies and Documents, no. 30 ([Rome], 1973), p. 87. Nino Pirrotta kindly informs me that since penna refers to a plectrum it may also be used synonymously for any instrument played with one — hence guitars and lutes, as well as plucked keyboards (private communication).

[60] I thank Margaret F. Rosenthal for bringing these letters to my attention. See Veronica Franco, Lettere dall'unica edizione del MDLXXX, ed. Benedetto Croce (Naples, 1949), pp. 19-20.

[61] On such questions see Rita Casagrande di Villaviera, Le cortigiane veneziane del cinquecento (Milan, 1968); Georgina Masson, Courtesans of the Italian Renaissance (New York, 1975); and Anthony Newcomb, "Courtesans, Muses, or Musicians? Professional Women Musicians in Sixteenth-Century Italy," in Women Making Music: The Western Art Tradition, 1150-1950, ed. Jane Bowers and Judith Tick (Urbana and Chicago, 1986), pp. 90-115.

The singer vaunted here is Franceschina Bellamano, as confirmed by the sonnet's contemporary editor Dionigi Atanagi.[62] As early as 1545 the music theorist Pietro Aaron's Lucidario in musica listed Bellamano among Italy's renowned "Donne a liuto et a libro."[63] In Ortensio Landi's Sette libri de cathaloghi of 1552 she ranked with Polissena Pecorina and the elusive Polissena Frigera as one of three most noted female musicians of the modern era.[64] Like Venier's sonnet, the Sette libri emphasized her instrumental skill by punning her name as "bella mano."

Several other solo singers appear in encomiastic literature linked to Venier. In one sonnet Venier joined the chorus of praises sung posthumously to the precocious singer-lutenist Irene di Spilimbergo, mythologized after her untimely death by members of his circle (Molino, Fenaruolo, Dolce, Amalteo, Muzio, Pietro Gradenigo, and Bernardo Tasso). In another he praised the singer and gambist Virginia Vagnoli, wife of Alessandro Striggio.[65] But the most lauded solo singer usually associated with the first decade of Venier's academy was the famed poet Gaspara Stampa. Although she was probably not a regular at their meetings, her close ties with intimates of the academy — especially Parabosco and Molino — and the sonnet she addressed to Venier make her presence there very likely.[66] Stampa's

[62] See Rime di Domenico Veniero, p. xv; the sonnet, Ne 'l bianco augel, che 'n grembo a Leda giacque, is no. 68 in Serassi's edition, p. 37. It appears in the anthology De le rime di diversi nobili poeti toscani, raccolte da M. Dionigi Atanagi, libro secondo, con una nuova tavola del medesimo . . . (Venice, 1565), fol. 11, where Atanagi's annotated tavola reads, "Ad una virtuosa donna, che cantava, & sonava eccellentemente di liuto, detta Franceschina Bellamano: al qual cognome allude nel primo Terzetto" (fol. K/2 4). See also Bussi, Umanità e arte, p. 36.

[63] Fol. 32. See also the references to Bellamano in Einstein, The Italian Madrigal 1:447 and 2:843. Einstein considered her — without evidence — to have been a courtesan, as he did virtually all female musicians; see Chap. 2 n. 51 above for a reassessment of the problematics involved.

[64] The full title of the former is Sette libri de cathaloghi a' varie cose appartenenti, non solo antiche, ma anche moderne: opera utile molto alla historia, et da cui prender si po materia di favellare d'ogni proposto che si occorra (Venice, 1552); she is listed as "Franceschina bella mano" on p. 512. I am indebted to Howard Mayer Brown for the reference and for the use of his copy of the book. Parabosco addressed a letter to Polissena Frigera (Frizzera) in his second book of Lettere amorose; see Libro secondo delle lettere amorose di M. Girolamo Parabosco (Venice, 1573), fol. 11'.

[65] For the verses to Spilimbergo see Rime di diversi nobilissimi, et eccellentissimi autori, in morte della Signora Irene delle Signore di Spilimbergo. Alle quali si sono aggiunti versi Latini di diversi egregij Poeti, in morte della medesima Signora, ed. Dionigi Atanagi (Venice, 1561), with Venier's poem on p. 33. Like Venier's sonnet to Franceschina Bellamano, this one plays with the words bella man. This might seem to suggest that the former could also have been intended for Irene or another female singer-lutenist other than Franceschina Bellamano, but Atanagi's authority as editor of both volumes (cf. n. 62 above) makes this unlikely. On the volume dedicated to Irene see Marcellino, Il diamerone, p. 5; Elvira Favretti, "Una raccolta di rime del cinquecento," Giornale storico della letteratura italiana 158 (1981): 543-72; and Anne Jacobson Schutte, "Irene di Spilimbergo: The Image of a Creative Woman in Late Renaissance Italy," RQ 44 (1991): 42-61. For a reprint of the table of contents see idem, "Commemorators of Irene di Spilimbergo," RQ 45 (1992): 524-36.

The information about Vagnoli was kindly related to me by David Butchart. It appears in a sonnet of Venier's (not included in Serassi's ed.) cited by Alfredo Saviotti, "Un'artista del cinquecento: Virginia Vagnoli," Bulletino senese di storia patria 26 (1919): 116-18.

[66] The sonnet to Venier is no. 252 in her Rime varie; mod. ed., Rime, ed. Bellonci and Ceriello, p. 247. On the question of Stampa's involvement in ca'Venier see Abdelkader Salza, "Madonna Gasparina Stampa, secondo nuove indagini," Giornale storico della letteratura italiana 62 (1913): 1-101, who delivers a negative opinion while adducing much evidence that can be interpreted to the contrary (pp. 22-23).

singing was continually exalted with the topos of weeping stones; Parabosco's letter in his Lettere amorose of 1545 is only one of many such references: "What shall I say of that angelic voice, which sometimes strikes the air with its divine accents, making such a sweet harmony that it not only seems to everyone who is worthy of hearing it as if a Siren's . . . but infuses spirit and life into the coldest stones and makes them weep with sweetness?"[67]

We know little of how these soloists' unpreserved music sounded. I imagine Stampa singing fairly stock melodic formulas for poetic recitation not unlike the ones printed in Petrucci's Fourth Book of Frottolas of 1505 as "modi" or "aeri," which matched different melodies to different poetic forms — sonnets, capitoli, and so forth.[68] Such melodies were entirely apt for the poet-reciter, for whom display of original verse was the main point. They could be invented or borrowed, and reapplied stanza after stanza with creative variations and ornamentation, the patterns reshaped according to the poem's thematic development and the performer's inspiration.

The process is simple enough to try by applying Petrucci's melodies to Stampa's own verse. What emerges from such an exercise is how very singable her lyrics are — not only in the musicality of their scansion and sound groups, but in their thematizing of the very process of reciting in song.[69] Frequently Stampa's verse begins by summoning a friend, lover, or muse with a vocative rhetorical device in a way that might invite some kind of musical intonation. In the opening of Stampa's capitolo no. 256 we hear an apostrophic call to a muse that suggests this kind of intonation, replete with allusions to singing, melodic qualities, and the emotions they engender.[70]

Musa mia, che sì pronta e sì cortese My muse, you who were so quick and so kind

A pianger fosti meco ed a cantare To weep with me and to sing

Le mie gioie d'amor tutte, e l'offese Of all my joys of love, and the hurts

In tempre oltra l'usato aspre ed In modes beyond the usual harsh and bitter

amare ones,[71]

Movi meco dolente e sbigottita You move with me dolefully and dismayed,

Con le sorelle a pianger e a gridare . . . With your sisters weeping and crying out . . .

[67] "Che dirò io di quella angelica voce, che qualhora percuota l'aria de' suoi divini accenti, fa tale sì dolce harmonia, che non pura a guisa di Sirena fa d'ognuno, che degno d'ascoltarla . . . ma infonde spirto e vita nelle più fredde pietre, facendole per soverchia dolcezza lacrimare?" (Libro primo delle lettere amorose di M. Girolamo Parabosco [Venice, 1573], fol. 21'). Molino also referred to Stampa as a siren ("Nova Sirena"); see Salza, "Madonna Gasparina Stampa," p. 26, and for Ortensio Landi's praise of her musical prowess, pp. 17-18.

[68] This book (RISM 15055) contains untexted melodic formulas for a "Modo de cantar sonetti" (fol. 14) and an "Aer de versi latini" (fol. 36), as well as a texted "Aer de capituli," Un solicito amor (fol. 55'), for which different texts in capitolo form can be supplied. It is reprinted in Ottaviano Petrucci, Frottole, Buch I und IV: Nach dem Erstlingsdrucken von 1504 und 1505 (?), ed. Rudolf Schwartz, Publikationen älterer Musik, vol. 8 (Leipzig, 1935; repr. Hildesheim, 1967).

[69] The latter forms the subject of a study by Janet L. Smarr, "Gaspara Stampa's Poetry for Performance," Journal of the Rocky Mountain Medieval and Renaissance Association 12 (1991): 61-84.

[70] See also sonnet 173, Cantate meco, Progne e Filomena, and Ann Rosalind Jones's analysis of it as "an exchange of sympathy and song," The Currency of Eros: Women's Love Lyric in Europe, 1540-1620 (Indianapolis, 1990), pp. 138-39.

[71] I should emphasize that my use of "modes" for tempre here does not mean to imply the full panoply of technical traits linked with sixteenth-century modal theory. I intend instead the more general sense of melodies or melodic gestures using characteristic intervallic relationships, especially as they might have been conceived within a broad cultural consciousness as evoking affects.

In recitation for terze rime such as these the three poetic lines of the capitolo's stanzas would each be matched with a single musical phrase and the overall poetic prosody of each strophe thus shaped by a larger tripartite architectural scheme. Tunes for reciting such stanzas typically have a simple progressive shape that defines the keynote at the start, migrates above it, and then sinks to a clear return. The anonymous setting of Jacopo Sannazaro's capitolo Se mai per maraveglia alzando 'l viso, as arranged by Franciscus Bossinensis for lute and voice and printed by Petrucci in Tenori e contrabassi intabulati col soprano in canto figurato . . . Libro secundo in 1511, suits Stampa's capitolo especially well (see Ex. 1, where the music is given with Sannazaro's text replaced by Stampa's).[72] The arrangement offers up a preludial series of freely iterated, improvisatory chordal arpeggios that preface the recitative-like opening of the tune. This in turn leads into a more melodious excursion at the tune's center.[73] In Ex. 1 I have underlaid the first stanza of Stampa's capitolo to which she could have applied grace notes, cadential decorations, rhythmic alterations, and other forms of improvisation here and in subsequent stanzas.

Of course, Stampa could also have used newer formulas, or made them up herself. A remarkable discovery by Lynn Hooker concerning Stampa's only two canzoni, nos. 68 and 299, lends supports to the latter alternative.[74] Hooker points out that the two share precisely the same versification scheme and, moreover, that the first of them, Chiaro e famoso mare, bases its content, narrative, and verse structure on Petrarch's Chiare fresche et dolci acque. We know that canzoni were among the least fixed of repetitive forms and therefore the least susceptible to repetitive melodic formulas; they could use stock melodic archetypes traditionally linked with settenari and endecasillabi, respectively, but the method of pairing, separating, concatenating, and varying the melodies has to have been keyed (at minimum) to the particular formal scheme of each individual canzone. The unusual formal identity of the canzoni in this trio (including Stampa's two and Petrarch's Chiare fresche) might alone be grounds to suspect that Stampa performed all three with the same melodic

[72] Knud Jeppesen, La Frottola, 3 vols. (Copenhagen, 1968), 1:118, lists the piece as "Laude?" My attribution of the poem to Sannazaro is based on Iacobo Sannazaro, Opere volgari, ed. Alfredo Mauro (Bari, 1961), pp. 210-11, where it is given with the rubric "Lamentazione sopra il corpo del Redentor del mondo a'mortali."

[73] This example seems to me to suit Stampa's poem for use as a capitolo formula better than the generic "aer de capituli" published by Petrucci in RISM 15055, since the latter is more lyrical than recitational and rather foursquare in its metric-melodic contours. (See fol. v' of Petrucci's Book Four, ed. Kroyer, p. 99.) Kevin Mason shows how unusual the idiomatic, improvisatory style of Bossinensis's ed. of Se mai per maraviglia is among early- to midcentury lute books; see "Per cantare e sonare: Lute Song Arrangements of Italian Vocal Polyphony at the End of the Renaissance," in Playing Lute, Guitar, and Vihuela: Historical Practice and Modern Interpretation, ed. Victor Coelho (Cambridge, forthcoming). See also Howard Mayer Brown, "Bossinensis, Willaert and Verdelot: Pitch and the Conventions of Transcribing Music for Lute and Voice in the Early Sixteenth Century," Revue de musicologie 75 (1989): 25-46, who argues that Bossinensis initiates a tradition for publishing lute books that largely demonstrate how to arrange "apparently vocal polyphony" for solo performance (rather than how to play lute accompaniments in the idiomatic, improvisatory style).

[74] Hooker's study was produced in my seminar on Petrarchism at the University of Chicago. In its current form it bears the title "Gaspara Stampa: Venetian, Petrarchist, and Virtuosa" (seminar paper, Winter 1992).

Ex. 1.

Anon. capitolo setting, Se mai per maraveglia alzando 'l viso, with a capitolo text

by Gaspara Stampa substituted for Sannazaro's capitolo; in Tenori e contrabassi

intabulati col sopran in canto figurato per cantar e sonar col lauto: libro secundo.

Francisci Bossinensis (Venice, 1511), fols. vv -vi.

formulas and that the formulas were either her own or adapted by her to suit the special requirements of the three canzoni's shared formal structures. Hooker virtually clinches the argument that this was so by relating the nexus of canzoni to Orazio Brunetti's letter to Stampa in which he begs re-entry into her salon with the plea that he has missed her marvelous singing and especially her rendition of Petrarch's Chiare fresche.

Whether the melodies were Stampa's inventions or adaptations from preexistent formulas, her practice would almost certainly have matched melodic phrases to poetic lines, rather than to syntactic structures (which in any case do not always correspond to line lengths). This approach is far from high-styled Venetian madrigalian practice. It comes closer to madrigalian styles linked in their text-music relationships, harmonic patterns, and free treble-dominated declamatory rhythms to the world of improvvisatori, the most striking manifestations of which are the madrigali ariosi.[75] The music's role in both solo singing and polyphonic imitations thereof — but especially in singing by the poet her- or himself — was to provide the verse with a musical dress. This did not mean that the goal of moving the listener through the efficacious joining of words and voice was any less strong for song than polyphony; indeed the reverse could have been true. It means instead that song did not aim for a sovereign aesthetic equal to the poetry in the same way elaborate polyphonic settings did.

In 1547 the madrigalist Perissone Cambio dedicated to Stampa his Primo libro di madrigali a quatro voci, praising her musical talent, her "sweet harmonies," and recalling her epithet of "divine siren."[76] Perissone's dedication confirms the connection we might infer from Parabosco's letter to her cited earlier — a connection, that is, between Stampa, the cantatrice, and Venetian polyphonists. Yet the volume's contents show even more importantly that their distinct performing traditions — written polyphony and recited song — at times merged. Perissone's four-voice madrigals set two distinct kinds of verse: weighty Petrarchan sonnets and lighter ottave, madrigals, and ballatas, most of which were short. Frequently homophonic, these four-voice settings traded in great melodic charm. They strike a course midway between the tradition of melodious song practiced by Stampa and the thick, motetlike style found in the new five- and six-voice Venetian madrigals. Perissone, in other words, brought to many of his four-voice madrigals that

[75] Madrigali ariosi were issued by the Roman publisher Antonio Barrè in three different editions, first printed in 1555, 1558, and 1562, respectively. See James Haar, "The Madrigale Arioso: A Mid-Century Development in the Cinquecento Madrigal," Studi musicali 12 (1983): 203-19, and (with particular attention to the relations of harmony, melodic phrasing, and verse lines) Howard Mayer Brown, "Verso una definizione dell'armonia nel sedicesimo secolo: sui madrigali ariosi di Antonio Barrè," Rivista italiana di musicologia 25 (1990): 18-60.

[76] The dedication and translation are given in Chap. 9, p. 373. A facsimile of the dedication also appears in my edition of the book, Sixteenth-Century Madrigal, vol. 3 (New York, 1989), p. xvi.

indefinable, memorable, and tuneful quality that Pirrotta linked to the Italians' notion of "aria"[77] — a quality particularly striking in them since they were published after Perissone issued his first book of five-voice madrigals in a style close to the Musica nova.

The more tuneful approach of Perissone's Madrigali a quatro voci resembles Donato's four-voice settings of Venier's three patriotic stanzas for the dual celebration of Ascension Day and the Marriage of Venice to the Sea.[78] I offer the text of one of them below.

Gloriosa, felic'alma, Vineggia, Glorious, happy soul, Venice,

Di giustitia, d'amor, di pace albergo, Shelter of justice, of love, of peace,

Che quant'altre cità più al mondo pregia You who, first in honor, leave behind

Come prima d'honor ti lassi a tergo. All other cities praised in the world: 4

Ben puoi tu sola dir cità d'egregia; Well may you alone be called city of renown;

Stando nell'acqu'in fin al ciel io mergo, I immerse myself up to Heaven in water,

Poichè mi serb'anchor l'eterna cura, Since the eternal cure still serves me,

Vergine, già mill'anni intatt'e pura.[79] Virgin, a thousand years intact and pure. 8

Donato's setting (Ex. 2) avoids the blurred outlines of the new Willaertian madrigal — a style in which the young composer was by then already proficient.[80] Instead it celebrates the poem's association of the Virgin with the Marian virtues of Venice by means of lucid textures and well-defined successions of textual units. The simple F-mollis tonality concentrates its cadences exclusively on F and C and continually emphasizes the unassuming modal degrees of F, C, and A to create pleasing melodic outlines. Its graceful arioso melodies are enhanced by a fairly harmonic bass line, both treble and bass thus recalling characteristics of songlike genres. In this way the words project clearly to suit what was probably an outdoor performance on the occasion for which it was written, with instruments doubling vocal parts. But it may also have been heard with reduced forces in chamber performances at salons like Venier's. In such a venue

[77] See Pirrotta's "Willaert and the Canzone villanesca," in Music and Culture in Italy, p. 195, and Nino Pirrotta and Elena Povoledo, Music and Theatre from Poliziano to Monteverdi, trans. Karen Eales (Cambridge, 1982), pp. 247ff.

[78] They appeared in Baldissara Donato musico e cantor in santo Marco, le napolitane, et alcuni madrigali a quatro voci da lui novamente composte, corrette, & misse in luce (Venice, 1550). See Ellen Rosand, "Music in the Myth of Venice," RQ 30 (1977): 527-30, with particular attention to the modernized reinterpretations of Venetian civic mythology in Venier's poems.

[79] Rime di Domenico Veniero, p. 40. (Here and elsewhere, I give the orthographical variants as they appear in the musical source.) Parabosco seemingly glossed the first line of the poem as the last line of his own Stanze in lode de l'inclita città di Vinegia, first published in his Rime (Venice, 1547), fols. 19-21': "di virtù tante Iddio t'adorna, et fregia, / felice gloriosa alma Vinegia" (15.7-8). Perhaps Venier's stanzas already existed by that time. For a modern edition of Parabosco's Stanze see Bianchini, Gerolamo Parabosco, pp. 461-64.

[80] When only about eighteen years old Donato had already published a highly proficient madrigal in the Willaertian style, a setting of Petrarch's sonnet S'una fed'amorosa, s'un cor non finto (see Chap. 9 n. 70 below). It was included in Cipriano de Rore's Terzo libro di madrigali a cinque voci of 1548 (RISM 15489); for a mod. ed. see my "Venice and the Madrigal in the Mid-Sixteenth Century," 2 vols. (Ph.D. diss., University of Pennsylvania, 1987), 2:656-67.

Ex. 2.

Donato, Gloriosa, felic'alma, Vineggia (Domenico Venier), incl.; Le napolitane,

et alcuni madrigali a 4 (Venice, 1550), p. 20.

(continued on next page)

(continued from previous page)

Ex. 2

(continued)

(continued on next page)

(continued from previous page)

Ex. 2

its text could articulate the academy's alliance with the same civic values that sound less directly in the copious Bembist lyrics its members produced.

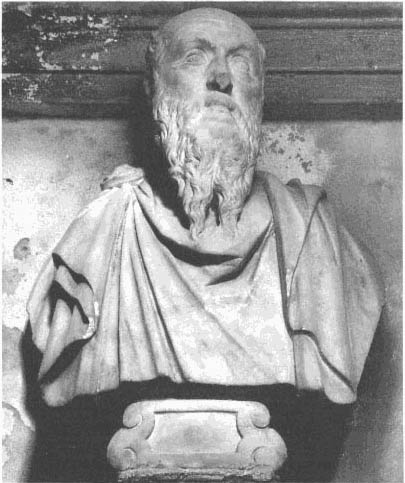

Since musical activity in Venier's salon functioned as a pastime rather than a central activity, and since the academy kept no formal records of its meetings, concrete evidence of links between musicians and men of letters is scarce. Parabosco, as a key figure in both the musical establishment at San Marco and the literary circle of Venier, forms the primary liaison between musicians and writers. Among literati the most intriguing link may be found in the figure of Molino, Venier's aristocratic poet friend and acquaintance of Parabosco (who sent him two books of his Lettere amorose ).[81] Molino's stature in Venetian society was considerable, despite family battles that cost him an extended period of poverty and travails (on which more in Chap. 6).[82] A bust sculpted by Alessandro Vittoria for the tiny Cappella Molin in Santa Maria del Giglio — where a great number of reliquaries owned by the family are still preserved — portrays Molino as the embodiment of gerontocratic wisdom (Plate 18).

In 1573 his posthumous biographer, Giovan Mario Verdizzotti, wrote that of all the arts Molino had delighted in understanding music most of all.[83] The remark is supported by earlier evidence. Several composers based in Venice and the Veneto — Jean Gero, Francesco Portinaro, and Antonio Molino (no relation) — set Molino's seemingly little-accessible verse to music before its publication in 1573, four years after the poet's death.[84] As early as 2 April 1535 Molino seems to have tried to obtain a frottola, Se la mia morte brami, by one of the genre's greatest exponents, Bartolomeo Tromboncino. The work had been requested of Tromboncino (then in Vicenza) by the Venetian theorist Giovanni del Lago, who apparently was in such a hurry to procure it that Tromboncino had no time to rewrite the original lute-accompanied version in a more madrigalesque vocal arrangement with the addition of an alto part, as had apparently been asked of him.

You ask me for the draft of Se la mia morte brami, and I send it to you most happily, advising you that I have written it only for singing to the lute, that is, without alto. For this reason, for whoever should want to sing it [a cappella], the [missing] alto would produce a serious wrong. Had you not had so little time, I would have

[81] Cited in Bianchini, Girolamo Parabosco, pp. 420-21 n. 2.

[82] See Chap. 6 nn. 11-14 below. The most extensive modern work on Molino is that of Elisa Greggio, "Girolamo da Molino," 2 pts., Ateneo veneto, ser. 18, vol. 2 (Venice, 1894), pp. 188-202 and 255-323.

[83] "[D]i Musica . . . egli sommamente intendendosene dilettava" (Molino, Rime, p. [6]).

[84] The settings are Amore, quanta dolcezza in Gero's Book 2 a 3, 2d ed. (Venice, 1556), of which the first ed. is lost; and Come vago augellin ch'a poco a poco in Portinaro's Book 1 a 4 (1563), the latter also set in Antonio Molino's I dilettevoli madrigali a quatro voci (1568). The publication of Molino's posthumous canzoniere in 1573 led to many further settings, including three by Andrea Gabrieli, one by Luca Marenzio, five by Massaino, three by Pordenon, and twenty-four by Philippe de Monte, none of them listed in Il nuovo Vogel.

18.

Alessandro Vittorino, Bust of Girolamo Molino, Cappella Molìn,

Chiesa di Santa Maria del Giglio, Venice.

Photo courtesy of Osvaldo Böhm.

arranged it for singing in four parts, with no one part obstructing any of the others, and on my return to Venice, which will be at the beginning of May, if such an occasion arises, I shall fashion one of the sort mentioned above in order to make you understand that I have been and always shall be at your service. But please do me this favor: remember me to the magnificent and kindly Messer Girolamo Molino, that lover of artists ["virtuosi"], whom God by his grace should grant hundreds and hundreds of years of life.[85]

[85] "V.S. mi richiede la minuta de: Se la mia morte brami: et così molto volun tier ve la man do, ad verten dovi ch'io non la feci se non da can tar nel lauto cioè senza con tr'alto. Per che chi can tar la volesse il con tr'alto da lei seria offeso. Ma se presta [sic ] non haveste havuto, gli n'harei fatta una che se can ta ria a 4 senza im pedir lun laltro et alla ritornata mia a Venetia che sera a prin cipio de maggio se accadera gli nefaro una al modo supra dicto facen dovi in terder [sic ] ch'io fui et sempre sero minor vost ro facendomi pero questo piacere racoman darmi al magnifi co et gentilissimo gentilhomo amator de i virtuosi ms Hyeronimo molino che Dio cent'e cent'anni in sua gratia lo conservi." In musical contexts the term virtuosi generally referred to musicians, so here Molino is probably being called specifically a "lover of musicians." Quoted from I-Rvat, MS Vat. lat. 5318, fol. 188; Einstein, The Italian Madrigal 1:48, gives a translation along with a somewhat different version of the text, as does Jeppesen, La frottola 1:150-1. The entire manuscript of Vat. lat. 5318 has been transcribed and published along with glosses of each letter in English by Bonnie J. Blackburn, Edward E. Lowinsky, and Clement A. Miller, eds., A Correspondence of Renaissance Musicians (Oxford, 1991), with Tromboncino's letter on p. 869. I am indebted to Bonnie Blackburn for reminding me of the latter and sharing substantial portions of the Correspondence with me prior to its publication.

Tromboncino's allusion to the rushed nature of the request that prevented him from producing the four-voice version and his warm regards to Molino suggest that the work was wanted for a specific occasion and probably by Molino, rather than del Lago. The work is lost, but we may assume that it was either a traditional frottola or rather akin to one. As a genre, of course, the frottola was related to the tradition of solo singing practiced by Molino's good friend Gaspara Stampa.

Molino himself may have performed solo song, as Stampa seems to hint in a sonnet dedicated to him with the words "Qui convien sol la tua cetra, e 'l tuo canto, / Chiaro Signor" (Here only your lyre is fitting, and your song, / eminent sir).[86] In Petrarchan poetry the idea of singing, and singing to the lyre, is of course a metaphorical adaptation of classical convention to mean simply poetizing, without intent to evoke real singing and playing. But Stampa's poems make unusual and pointed separations between the acts of "scrivere" and "cantare" that suggest she meant real singing here.[87]

Other contemporaries specifically point up Molino's knowledge of theoretical and practical aspects of music. Six years after Tromboncino's letter was written, in 1541, Giovanni del Lago dedicated his extensive collection of musical correspondence to Molino, whom he declared held "the first degree in the art of music" (nell arte di Musica tiene il primo grado). Further, he claimed, "Your Lordship . . . merits . . . the dedication of the present epistles, in which are contained various questions about music. . . . And certainly one sees that few today are found (like you) learned . . . in such a science, but yet adorned with kindness and good morals."[88] Del Lago's correspondence, as will be seen in Chapter 6, was theoretically oriented in church polyphony. One of its most striking aspects is its recognition of connections between music and language that parallel those embodied in the new Venetian madrigal style. Del Lago insisted that vernacular poetry be complemented with suitable musical effects and verbal syntax with musical phrasing. In

[86] No. 261, vv. 12-13, from her Rime varie.

[87] Franco, who may also have done solo singing, does so too; see, for example, capitolo no. 2, v. 169, in Gaspara Stampa — Veronica Franco: Rime, ed. Abdelkader Salza (Bari, 1913), p. 241. I suspect that this is a feature of poetry conceived for an immediate audience — a distinctive aspect of a musician's verse, as both Stampa's and (to a lesser extent) Franco's was. This is a point made by Smarr, "Gaspara Stampa's Poetry for Performance." One should also note Venier's sonnet to Molino (Rime di Domenico Venier, no. 48, p. 26), which refers to the "suon delle tue note" (v. 6) — again, possibly with literal intent.

[88] "Vostra segnoria . . . merita . . . la dedicatione delle presenti epistole, nellequali si contengono diversi dubbij di Musica. . . . Et certo si vede che pochi al di d'hoggi si trovano (come voi) dottata . . . di tale scienza, ma ancora di gentilezza, et costumi ornata." This is the same collection of correspondence that contains Tromboncino's letter cited in n. 85 above — MS Vat. lat. 5318 (fol. [Í]).

discussing these relationships he developed musically the Ciceronian ideals of propriety and varietas.[89] His dedication to Molino therefore presents a fascinating bridge between patronage in Venier's circle and developments in Venetian music. Yet taken in sum these sources show Molino's musical patronage embracing two different traditions, each quite distinct: one, the arioso tradition of improvisors and frottolists; the other, the learned tradition of church polyphonists. Molino's connection with both practices reinforces the impression that Venetian literati prized each of them.

Indeed, informal salons like Venier's, with their easy mixing of diverse personal and artistic styles, were ideally constituted to accommodate different traditions. They were well equipped to nurture the kind of interaction of musical and literary cultures necessary to achieve a profitable exchange and, at times, a fusion of disparate traditions. As we have seen, this was accomplished in a variety of ways: in the appropriation of literary ideals by composers, so evident in the new Venetian madrigal; in the bifurcation of secular genres according to Italian and dialect, high and low; and in the continued commingling of the ideals of song with those of imitative counterpoint, seen both in Perissone's four-voice book of polyphonic madrigals and in Donato's settings of Venier's stanzas.