Five—

Work and Leisure in the Formation of Identity:

Muslim Weavers in a Hindu City

Nita Kumar

The most renowned and commercially important product of Banaras is the "Banarsi" sari, with a history of many millennia behind it and a working force that includes almost 25 percent of the city's population. These weavers are proud craftsmen who trace their presence in the city to anywhere between three hundred and a thousand years. They are Sunni Muslims, articulate about their beliefs, rituals, and religiosity. They refer to themselves as "Ansari" rather than by their old "caste" name, Julaha[*] , and consider the new name replete with suggestions about their character and behavior. They have no economic or social ties in the countryside or other cities, and call themselves unequivocally "Banarsi" ("of Banaras").

The characterization of their identity is not a simple task. If we begin with a consideration of them as an occupational group, that is what they primarily seem to be. If we discuss them first as "Muslims," we will find ample data to support a case for their religious or "communal" identity. They may further be labeled "urban," "lower class," the "poor," and perhaps a "closed social community." This chapter looks at different manifestations of identity, using the methods of both history and anthropology. The routine of work reveals the common elements of poverty, insecurity, and illiteracy, as well as the more positive aspects of a high level of skill and a lack of regimen in the workday, which are common to all artisans. The patterns of leisure demonstrate the common attachment to place and tradition, the practical demonstration of freedom, and the priority given to individual preference, taste, mood, and occasion in deciding the use of time. A consideration of the two—work and leisure activities—together, enables us to construct a suitably complex picture of what it means to be a Muslim weaver in the Hindu pilgrimage center of Banaras.

The Weaver as Artisan

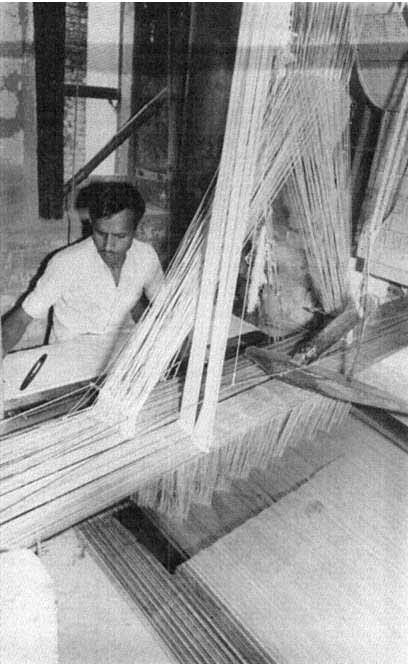

The first thing that defines a weaver is his work. The technological dimensions of the work consist of the difficulty of operating the pit loom, of weaving jacquard designs, and of maintaining unfaltering originality in every piece woven (see fig. 12). The stories and legends about the incomparability of the Banarsi sari and its attractiveness for all people in all times are part of the weaver's way of conceptualizing himself. The first reaction of the weaver to a question about his place in society is to bring down the three-by-one-foot cardboard boxes that house the Banarsi sari, if he is a prosperous or master weaver, or to open up the weaving side of the loom to reveal the precious product being created there, if he is too poor to have anything in store.

The weaving technology of Banarsi silk has not undergone major changes over the last century; in fact, in contrast to the fate of many other craftsmen and domestic industries, the lack of mechanization has been a powerful aid in its survival. The two simplifications introduced were the use of the jacquard machine in place of the intricate cotton-thread designs strung over the loom, and the adoption of the Hattersley domestic loom, both in about 1928 (for the technology, see DuBois 1986). While traders consider these changes to indicate a decline in traditional skill, weavers themselves consider them only labor-saving devices that leave the skill untouched.

Ironically, the corollary to their skill and excellence is poverty and insecurity. All artisans are poor, their lives characterized by the seemingly essential features of cottage industries: low capital investment, the control of the market by middlemen, the uncertain supply of raw materials, and the impossibility of achieving economies of scale beyond a point. All artisans are accustomed to insecurity as well, insecurity at the daily and weekly level attendant on earning by the piece, implying earning exactly as much as health and "mood" permits; and to largerscale periodic slumps dictated by the market, any of which may signal long-term decline. Their products are culturally valued ones, dependent on the vagaries of "fashion," and alternative products may outmatch them in dazzle at any time.

There have been two major periods of decline in the silk industry over the last hundred years, in the 1880s and the 1950s. In 1884 ten to twelve thousand Muslims of Banaras were reported to have gathered for special prayers, as their work was at a standstill (Bharat Jiwan , 15 Dec. 1884, 3). In December 1891 one thousand to twelve thousand weavers went to the house of the District Magistrate, Banaras, with a petition asking for lower grain prices and complaining of no work. The industry was so depressed that the government considered diverting all

Fig. 12

Brocade weaver in Banaras working at pit loom with jala[*] and jacquard attachments.

Photograph by Carley Fonville; thanks to Emily DuBois.

the weavers to a new industry of weaving carpets (GAD 155B 1891, Ind 110 1910, Ind 253 1911). Weavers in this period were supposed to be full of discontent: "The Julahas are a disaffected class of people as the weaving industry has given place to the piece-goods of British manufacture" (GAD 255B 1891 no. 30). In April 1891 they successfully persuaded Hindus not to hold their "river carnival," the Burhwa Mangal, in sympathy with their problems. Later in the year they were suspects in the riots related to the destruction of the Rama temple: they were supposed to have joined the Hindu "rascals" to create trouble for the government (GAD 255B 1891 no. 30 and see chapter 7). At this time, too, the leading weekly of the city and province made its only passing allusion to the decline in exports of silk from the U.P. (Bharat Jiwan , 26 Dec. 1892, 5). By 1900 there is no more mention of any trouble in the silk industry (Ali 1900). Banaras weavers were preparing to demonstrate their techniques and display their brocades at the Delhi Exhibition, and were referred to as "a prosperous community" (Bharat Jiwan , 5 May 1902, 7; Adampura TR 8-IV).

These periodic slumps are part of a cyclical process and do not detract from the overall expansion experienced by the silk industry in the last century. They do contribute to a feeling of insecurity, however, that is characteristic of all artisans. The consciousness of the weavers is colored moreover by smaller, more frequent ups and downs, and every weaving family uses an idiom of flux and change to describe its fate (see Bismillah 1986). Yet the weaver's world is an expanding one, and the overall progress in the industry—in the number of workers (see table 5.1), the volume of sales, the variety of markets (N. Kumar 1984)—does affect the weaver positively. As contrasted with the metalworker, the woodworker, the potter, and the painter, the weaver continues on top of the swift currents of change and has a positive outlook on the world, based on the recent history of his industry.

A small part of this is also composed of positive expectations from the government. A weaving school was opened in 1915, and agencies such as the All India Handloom Board were set up to tide over the crisis in the 1950s (UP Admin Rpt 1916, Ind 820 1922). Although most of the schemes for rationing of silk yarn, registration of looms, and loans to weavers have remained confined to paper, there is a sense of optimism about the government's role, which contrasts with the sense of other artisans, particularly metalworkers and woodworkers.

The positive outlook of weavers is further compounded by the progressive possibility of mobility in the industry. In about 1900 there were three main silk products in Banaras: kamkhwab[*] (brocade), material for specific apparel purposes, and plain silk yardage. Corresponding to

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

these were three levels of production: the dependent laborer working for the karkhanedar[*] , or firm owner, the dependent laborer working for himself at home, and the independent weaver or master weaver (Ali 1900; UP Admin Rpt 1882). Today there is relative homogenization of products, and almost every weaver is a weaver of Banarsi saris. The three levels of production continue to exist, constituting a hierarchy in relative well-being for the weavers: from the bottom up, laborer working under another's roof, weaver working at home for others, weaver working at home for himself. The difference between the earlier hierarchy and the present one is that now there is more mobility among the different levels, and today a laborer can conceivably move up the ladder in a decade or two to an independent weaver's status.

Poverty is one corollary of the nature of handicraft industry; control over space and time is the other. The home is the workshop, and work time is always time set by the artisan himself. Even when men work in another's place as laborers, the location still remains a domestic one. Even in the largest workplaces the total number of workers is never more than ten or twelve; there is direct interaction between them and the employer, and time remains the worker's, for payment is always by the piece. These conditions have not changed over the last century in that there has been no tendency for larger production units or a new ethic of production relations to emerge. When the Royal Commission on Labour gathered oral evidence on working hours, it found that in the Banaras silk and brocade industry hours were normally seven per day but could be as many as fourteen per day in the wedding season. But there were important features of the work which alleviated this problem. "A good deal of the work is done in the open—in the courtyard of the worker's house or even in the public street or lane . . . there is no discipline to observe. Rest and recreation is taken whenever the need is felt. Contact with the home and familiar surroundings is seldom interrupted. The usual amenities of social life are not disturbed" (Royal Commission of Labour 1931:154). This familiarity with "freedom" has become an integral part of the weaver's identity, as discussed further below.

On all these counts—the perceived level of skill needed for their unique work, the liberties with space and time possible within the dimensions of domestic handicrafts production, and the near guarantee of poverty—the world of the weaver is no different from that of the other artisans of Banaras, including the metalworker, wooden-toy maker, goldsmith, potter, painter, copper-wire drawer, embroiderer, and garland maker. Where he is at all different is in being the best off of the lot, a factor that contributes substantially to his construction of identity.

The Weaver as Ansari

All the different kinds of Muslim weavers—dependent, independent, and master, as also the owners of firms—call themselves Ansari. The exceptions are so few as to be negligible: a Muslim of a Pathan "lineage" or a barber "caste,"[1] who has wandered into the weaving profession through a series of unusual circumstances. The term "Ansari" is used in a number of ways. Trading or manufacturing firms and weavers who are expanding their production use "Ansari" as a "title" in their or their firm's name, such as Swaleh Ansari and Company. Many master weavers treat "Ansari" as part of their full name, such as Matiullah Ansari or Hafizullah Ansari. Poorer master weavers and all ordinary weavers, like all poor and uneducated Hindus, particularly of the lower castes, call themselves simply by their first names, such as Alimuddin or Jameel Ahmad. They may acquire an epithet ("Sahab," "Banarsi") if they achieve any distinction, but if required to give their "last name" for an official purpose such as in a school, bank, or hospital, they use "Ansari." All of them, if asked "what" they are, will reply not "Julaha[*] ," the term used for them by others, but "Ansari." The term is explained by them as referring to a biradari[*] or qaum , comparable to a Hindu endogamous caste in its traditional occupation, with implications of honesty and sincerity, thus infinitely preferable to "Julaha" with its allusions of poverty, stupidity, and backwardness (see Sherring 1872:345–46, Nesfield 1885:26, 131, J. Brij Bhushan 1958:73–74, Naqvi 1968:165, Ansari 1960:44).

This preference was largely responsible for the adoption of the new name as part of a larger movement for social uplift and higher status among both Hindus and Muslims around the turn of the century. The movement was formalized in the 1930s in the All India Jamat-ul-Ansar, a fact unknown to the great majority of Banaras weavers, who consider Ansari to be a broad definition of a lineage or descent group, or at least of an occupational community whose work was first inspired and sanctified by Hazrat Sees Paigambar alah-e-salam.

Such a "creation" of identity is a feature that may be witnessed from approximately the first quarter of this century in other artisan communities in Banaras as well. The metalworkers, Kasera by caste, call themselves Haihayavamshi Chhatri, although no one else calls them that. Goldsmiths, ironsmiths, and woodworkers are called Sonar[*] , Lohar[*] , and Barhai[*] by others, but refer to themselves as Vishvakarmas. Compared

[1] The four high Muslim "lineages" recognized in most of India are the Mughals, Sheikhs, Sayyads, and Pathans; the weavers, as Ansaris, now claim Sheikh lineage. These, and all occupations, such as butcher, sweeper, barber, and of course weaver (whether called Julaha or Ansari), are also regarded as castes.

with other artisans, the weavers have been the most successful in perpetrating their new identity.

The new identity that is put forward is based on occupation in each case, but goes beyond that to make a case for a certain kind of personality. The components of this differ considerably in the versions offered by the outside observer and by the member of the community. Ansaris maintain themselves to be a united people: all feel equal, as members of one family; anyone may marry another, in spite of income differences; and anyone may sit down and eat with another, in spite of status inequalities. These are sentiments voiced frequently by more prosperous Ansaris, although lower-class weavers do not contradict them if pressed to give an opinion. In actuality, marriages are preferably made between families of equal economic standing, and food is shared at festivals, but the occasion of sitting down together rarely occurs. What is in fact common to rich and poor Ansaris is not noted by them: certain aspects of lifestyle, such as house design and clothes.

The houses of all Ansaris have a similar pattern: a dark entrance, with very likely a latrine on one side, leading to an enclosed courtyard, with tap or hand pump. The karkhana[*] (loom or weaving room) is located on one side, or two, depending on prosperity, and stairs go up on the third. Above are the family rooms all around the central opening. The kitchen is on a separate mezzanine off the stairs, or on the roof itself. No furniture is kept except some string cots standing up during the day, and trunks and canisters of stores. There is a total separation of working and living areas, and the karkhana never doubles as sleeping or playing space for the family, though it does as sitting room for the weavers and their guests. Even the newest, most expensive homes of Ansari businessmen have this basic design, which may become elaborated with the multiplication of floors, rooms, and even courtyards, and the addition of rugs, television, and refrigerator.

The houses of metalworkers and other artisans of Banaras have the same design as well, leading to the conclusion that the decisive factors are occupation—the need for a karkhana at home—and culture, such as the understanding of convenience, as in the case of bathroom and kitchen. In other words, there is a Banarsi artisan house design, not a peculiarly Ansari one. When the pattern does not immediately seem obvious, it is always due to fraternal partitions that split the house in the center, resulting in disproportionately tall and narrow houses with only half a courtyard, rooms on only one side, and an even narrower, tunnel-like entrance.

Ansaris almost always wear a lungi, topped with a shirt or vest, and a gamchha[*] strewn over the shoulder. Muslims in other professions often dress this way, but not with any consistency. The choice of dress is an

interesting combination of the practical and the culturally preferred. A lungi suits the postures demanded by the pit loom, which does not explain why prosperous Ansaris who do not themselves weave habitually wear the lungi at home. It is perhaps a carryover from their weaving days, but more, it is closely associated with the Ansari identity. All other artisans dress also in lungi and gamchha[*] , though in knee-length lungis as opposed to the Ansari ankle-length version. The preference for this choice of clothes is articulated not in Ansari but in Banarsi consciousness. Clothes are supposed to emphasize your simplicity, your inner wealth, and the absence of need to make any kind of external show. Material display is vulgar and indicative of little but poverty, weakness, and shallowness of character (see also N. Kumar 1986). Ansaris and all other artisans dress the way they do, not simply because they are poor or because it is convenient, but because it is an idealized way of dressing.

After skill and poverty, what Ansaris cite as the most telling indicator of their community character is their illiteracy. This is mentioned matter-of-factly as a problem that undoubtedly leads to their proverbial "backwardness" in that it makes them easy victims at the hands of the middlemen, but a problem of such dimensions that it is completely outside their ability to tackle. The some thirty madrasa s[*] (Muslim schools) of the city have hardly 10 percent of the Muslim children of school age attending them, and an even smaller percentage attends the public and private secular schools of the city. The sardar s, the social leaders of the Ansaris, do not recognize education as one of the urgent goals before them. The reformist sects of Wahabis and Deobandis are somewhat more concerned,[2] but their numbers are small (5 to 10 percent of the population) and their influence is limited. The largest madrasa of the city, Islamia, as well as a new college, the Salfia Dar-ul-ulum, is Wahabi, but the ordinary weaver identifies with neither. Although the subject needs much further research, my estimate is that the fact of illiteracy, or at least the relative lack of education, contributes strongly toward the particular complexion of weavers' identity that I am describing in this chapter.[3]

The most interesting characteristic claimed to be shared by the Ansaris is their "simplicity" and "tenderheartedness" ("we are narmdil, dilraham "). While simplicity may be understood in terms of lifestyle and lack of material ambition, both of which are easily observed and sup-

[2] An excellent background and discussion of the Wahabis (Ahl-i-Hadith) and Deobandis is given in Metcalf 1982.

[3] In research conducted recently, I have looked at the differences in popular perceptions that result with school education. This work is being written up, and the conclusions are not yet quite clear.

ported by our data, the idea of "tenderheartedness" is a more puzzling one. It seems to be the absolute counterpoint to the version of those who have a relationship of dominance over them: the government, especially in British days, in its regard of them as "bigoted" (GAD 210B 1892; see also G. Pandey 1983b: 19–28), and the middlemen and master weavers, who complain unceasingly of their love of idleness. The weaver's tenderheartedness is an aspect of his self-image, as someone urbane and cultured, who has perfected an unerring philosophy of contentment. He will work himself to the bone, but will cherish his freedom. "Ansaris are not afraid to work. They will work twelve hours a day, but they cannot do naukri[*] (service) because then we will become slaves."

Curiously, all nonweavers consider that weaving is easy, leisurely work, and that weavers are easygoing people. In the opinion of upper classes, "These weavers are too fond of mauj and masti[*] (carefreeness, fun). Whenever they feel like it, they will close up their karkhana s[*] and go for a stroll." To support this, half a dozen festivals are cited when work is suspended for days at a stretch and the fact that the end of one length of warp marks the appropriate time to take a few days as holiday. Most of these negative judgments are identical to those made of other artisans by their suppliers and buyers. Like other artisans, Ansaris never feel obliged to defend themselves on these counts. Leisure is considered as fundamental as work. What is described derisively as "love of idleness" by outsiders is regarded very positively by Ansaris as part of their identity.

The Weaver as Muslim

Ansaris regard their religiosity as an inalienable part of their identity: the complement to being poor, illiterate, simple, and sincere is a purity and directness of faith. Regarded as fervent, passionate, and bigoted by others, particularly by British administrators in the last century of their rule, they consider themselves very positively as "strong of faith" (dharm ke pakke[*] ) and "firm to their tradition" (usul[*]ke[*] pakke ). Their work itself is considered, as with every Hindu caste in its hereditary occupation, a sanctified task. Nyaz[*] (a food offering to be later distributed to the attending company) is given to the Paigambar with whom the craft originated, at the very beginning of one's career. Other Muslims in other professions similarly have a patron saint to whom they offer up, as it were, their efforts. For instance, zardozi[*] workers (embroiderers in gold and silver thread) consider their craft to have been started by Hazrat Yusuf alah-e-salam, in whose name are offered food and prayers, and whose anniversary is celebrated as a minor festival, Huzur ki miraj.

The religiosity of the Ansaris finds expression in their self-description, in which faith always finds a place. It is equally evident in what they do, that is, in their enthusiastic celebration of religious festivals, their visits to shrines, and their belief in pirs. Their religiosity is problematic, however, for their community leaders. Most of these leaders belong to the reformist sects of Wahabis and Deobandis, known for criticizing the very activities that the Ansaris prize most: their dependence on pirs, their visits to shrines, and the fairs and festivity they enjoy during a dozen celebrations during the year.

The chief festivals of the Muslims are c Id[*] (c Id ul Fitr[*] ) and Baqr c Id (c Id ul Zuha), when special foods and new clothes are ideally required by every member of the family. On both occasions, the namaz[*] (prayers) is mentioned as the main event and as the marker of the specialness of the day. The poorer weavers find it impossible to live up to the ideal image of the festivals in terms of feasting and celebration. For them, these are the major holidays of the year when they may close their karkhana s[*] for a week to ten days. Depending partly on the time of year in which these festivals fall, the holidays are occupied with outings, pleasure trips, visits to relatives, and picnics. The ideal of c Id as the reassertion of solidarity for Muslims is very strong, so that even while households vary drastically in their ability to afford festival food and clothes, the perception of most participants is that of unity and mutual sharing.c Id can also, on occasion, stand for a more pragmatic assertion of solidarity, as at the time of the special namaz at Banaras's Idgahs. Two of these particularly, Lat[*] and Gyan[*] Vapi[*]masjid , are sacred spaces in historical dispute between Hindus and Muslims. While no communal outbreak has actually occurred at c Id in Banaras, the situation has often become a "sensitive" one at these places (Bharat Jiwan , 11 May 1891, 8; UP Admin Rpt, 1924–25; Chauk and Adampura TFR). In everyday life, Hindus and Muslims conduct their respective worship without getting in each other's way, nor is there the memory of any actual violence associated with the places. But at c Id and Baqr c Id, the very presence of scores of armed policemen and elaborate preparations by the administration make the places seem like the settings for familiar, prerehearsed scenarios.

Baqr c Id also includes the ritual of the sacrifice of a goat (in the past a cow or a buffalo) or even a camel, followed by sharing of the meat among family, neighbors, and the poor. The less prosperous weavers can afford neither a goat, nor, as at c Id, new suits of clothes for everyone. Nor do they "feast" unless invited to do so by patrons, employers, and wealthier acquaintances. As at c Id ul Fitr, some presents of food, clothes, and cash pass from rich to poor, but solidarity is more an ideal than a reality. Except at the time of namaz , the festivals do not become

intense as occasions of identity. The absence of public processions and meetings serves further to diffuse the unity of the occasion. While the symbolism of Baqr c Id[*] , with its slaughter, blood, and feasting on meat, remains the most foreign of all Muslim festivals for Hindus, there is again no communal quarrel on record on Baqr c Id in Banaras, a fact that contrasts with the experience of the rest of the province (Bharat Jiwan , 7 Aug. 1893, 6; 19 Dec. 1912; Aj , 10 March 1938, 3; UP Admin Rpt, 1917, 1919, 1924, 1926, 1929; Pandey 1983a; Freitag 1980; Yang 1980). Even the cow, for all its potency as a symbol in a place like Banaras, has never been a political problem in the city. Cow slaughter has been banned since the 1950s, and its memory does not serve to arouse anyone.

The other major festivals of the Muslims, Muharram and Barawafat, seem to provide a more explicit context for an assertion of a "Muslim" identity. They have both been expanding in recent years and bear strong outward resemblance to Hindu celebrations that are likewise expanding, such as Durga, Saraswati, Govardhan, and Vishvakarma Puja. Muharram is the better known and is celebrated in Banaras with great pomp (shan[*] ) by both Shias (a microscopic minority) and Sunnis (all the weavers). The observation of Muharram may be analyzed in two parts: (1) the establishment of the tazia (the replica of the martyr Husain's tomb) on the chauk (platform) of the muhalla[*] (neighborhood); and (2) the processions on the tenth day of the month, each carrying a tazia for immersion or burial, and all other processions in the next fifty days, featuring battle symbols (calam ), marriage symbols (mehndi[*], dulha[*] ), and symbols of martyrdom (Duldul, the horse of Husain). Each of these two parts may in turn be interpreted as reflecting both Islamic identity and the identity of otherwise defined populations, and it is necessary to sift the different aspects.

The majority of tazias are constructed out of paper, cloth, wood, and other materials by professional atishbaz[*] (manufacturers of fireworks), and financed by the contributions of the muhalla . Thus the muhalla is the taziadar for the most part and not, as elsewhere in India, an individual (see Bayly 1975). The tazias become a focus of inter-muhalla competitiveness, particularly for children and young men. Around the tazia take place wrestling, lathi- and sword-wielding demonstrations, and the singing of the special poetic form called marsiyah[*] (see Sadiq 1984:20). All of these are specimens of the skill, talent, and excellence of the muhalla in implied competition with others. The larger symbolism of the tazia-on-the-chauk is that of Islam, and in Banaras not Shia or Sunni, but nonsectarian Islam. There are two spaces in Banaras each shared by a tazia chauk and a Hindu shrine, and, as with the major mosques, the places become annually vulnerable to violation by one community of the perceived rights of the other.

The processions (julu s[*] ) are similarly complex phenomena. The tazia julu[*] is very old in Banaras, having supposedly been introduced in 1753 (Siddiqi n.d.). In its popular form, it consists of a shoulder-borne tazia surrounded by crowds of mourners who chant, cheer, lament, and simply crowd along. There are one or more anjuman ("clubs"), singing marsiyah[*] ; there are one or more akhara[*] (also "clubs"), demonstrating their skill with the lathi, the sword, and dozens of other lesser-known instruments. Each procession is identified with a muhalla[*] , sometimes with a group of muhalla s[*] called after the dominating one. Together with this taken-for-granted muhalla competitiveness occurs the presentation of Islam to non-Muslims. Many of the tazia processions pass through crowded localities in the center of the city where lanes are only a few yards wide. Common threats to the sacredness of the occasion arise from possible collision between relatively oversized tazias or absolutely oversized calam , and low tree branches or telephone wires. A collision portends Hindu-Muslim conflict: the locality, the surrounding houses and porches, and the public spaces being Hindu, the "victimized" processionists Muslim, and the offending tree probably the sacred pipal. Such potentially explosive situations have occurred throughout the last hundred years (Chauk and Dasashwamedh TFR) but have been saved by the timely intervention of authorities and volunteers. In Adampura, a tazia is taken through Gola Hanuman Phatak, which has a temple to Hanuman at the crossroads in the center (see fig. 13; compare with fig. 15). The main business of the day is to keep the temple and the oversize tazia from touching each other. The task is performed by dozens of policemen, officers, and community leaders, some of whom physically hoist it over a threatening bend of the street. The provocateurs from whom a breach of peace is feared may be Hindus or Muslims (according to which side is reporting), but are clearly professional trouble-makers (budmash, khurafati[*] ), according to both. It does not occur to either side to redefine the boundaries of rights, to make it possible, for example, for the tazia to avoid that lane altogether, or to refashion the temple walls to change their angle slightly. The event has taken on the character of a local drama, and as such, its tension, intensity, and accompanying fun are very localized. Hindus and Muslims in other parts of the city, even in other parts of the same ward, are neither knowledgeable about the excitement nor impressed by it. It was described to me with many dramatic flourishes by the chief officer of the local police station, Adampura, who functions as the master of ceremonies on the occasion, before I had a chance to witness it. As I suspected and was able to confirm later, other police officers in the city were not aware of the proceedings at Gola Hanuman Phatak.

If what makes Muharram interesting is its proliferation in terms of processions, what is fascinating about Barawafat is its very invention:

Fig. 13

Tazia being paraded at Muslim observance of Muharram. Procession took

place in 1987 at Gola Hanuman Phatak (the temple of Hanuman), in Adampura

ward. All the houses are Hindu; the temple's platform is visible on the right,

protected by a row of policemen. Photograph by Nita Kumar. (Compare with

fig. 15.)

the day of both the birth and the death of the Prophet, in Banaras it is celebrated most loudly by the Sunnis as the former, and takes the shape of a rejoicing (jashnc Id[*] Milaud-ul-Nabi[*] ). At the core of it lies competitive performance by anjuman s of the poetical form called nat[*] , around which is constantly growing and becoming elaborated the accompanying paraphernalia of lights, paper decorations, flags, loudspeakers, stages, trophies, and all-night mela activity, including stalls of edibles, balloons, and toys. None of this was known two or three decades ago (Chauk TFR). Barawafat was an important festival, but observed only in the mosques and the home, with the recitation of milaud sharif , without a hint of competition, amplification, mela-like decoration and all-night festivity. The young do not remember a past when Barawafat in its present form was totally unthought of. The festival is also expanding in the equally interesting direction of the multiplication of locales. Dalmandi muhalla[*] in Chauk ward was the only center for Barawafat celebrations until about two decades ago. Now it is Dalmandi on the eleventh day of the month, Alaipura on the twelfth day, Madanpura on the thirteenth, Kotwa and Baribazar on the fifteenth, Ramnagar and Gauriganj on the sixteenth, and Shivala on the seventeenth.

While Muharram partially represents Islam to outsiders, we have seen how it also renews and furthers muhalla differences. The very residential patterns of the city work in both an organizational and an ideological way to weaken any potential alignment of "Muslims" as one unit. Weavers are distributed over most of the wards of the city and are concentrated in two, known as Alwipura (or Alaipura, the two wards of Adampura and Jaitpura) and Madanpura (all the muhalla s[*] of Dasashwamedh ward around the muhalla Madanpura). The latter sees itself as extant for almost a millennium, from the first Muslim invaders to the city, and to be the oldest center of the silk-weaving craft. The northern localities of Alaipura, though older in terms of absolute settlement, became important for weaving much later, and were accepted as integral parts of the city only in the eighteenth century (Nomani 1963; Siddiqi, n.d.). The weavers of Madanpura emphasize their absolute superiority over those of all other wards, characterized as "rural" (dehati[*], gawar[*] ), backward, crude, and uncultured. The weavers of these other wards, equally self-sufficient, progressively prosperous, and more numerous than the Madanpura weavers, do not react with actual hostility to the opinion of their backwardness. In reply, they stress their simplicity, honesty, and unspoilt nature, and prefer not to intermarry with Madanpura. Indeed, it is the boast of both parts of the city that one will never find in either part a wife who is from the other part. This ideological distancing is constant, and overcoming it would require a very powerful force that is not provided by any festival: even the c Id na-

mazes are read by the Alwipurites at the Lat[*] and by the Madanpurites at Gyan[*] Vapi[*] . Muharram particularly provides a referent limited to onemuhalla[*] or a group of muhalla s[*] regarded as one. Each procession is one of many, showing off precisely its superior tazia, its skilled celebrants, its akhara[*] competing with all others in talent and training.

Barawafat, even more than Muharram, cannot be understood as reinforcing the social solidarity of the whole Muslim community. The main separation that occurs is between muhalla s. The chief actors at the event are the anjuman s, and each anjuman consists of young enthusiasts whose social base is the muhalla , or proximity of residence, and who buy or learn poems from a poet of their choice. The very expansion of the celebration to new localities is indicative of the identification made by people with their immediate residential area, and states the friendly rivalry of muhalla s in their attainment of cultural refinement and their passion for a lifestyle of well-measured enjoyment.

There are three other kinds of divisions within Muslims which are well exemplified by Barawafat. Unlike the other two c Ids[*] , it is not a festival (tyohar[ *] , cId[*] ) in the strict sense of one established by Muhammad. It falls in the grey zone between classical, ordained celebrations and local, folk ones, being unequivocally condemned by imams and maulanas while passionately favored by ordinary weavers. The process described as "Islamic revitalization" has met with limited success in Banaras, and is in my view neither as simple nor as unopposed and unidirectional as is made out by certain scholars (Robinson 1983; see Veena Das 1984). The Wahabis and Deobandis, constituting hardly 10 percent of the Muslim population of Banaras, are no doubt preoccupied with it. Among their successful ventures in reform over the last century is the simplification of marriage ceremonies, rejection of music at life-cycle rites, and maintenance of strict dowry and divorce rules (Siddiqi, n.d.). But their intolerance for most of the practices that constitute pleasure and entertainment for ordinary weavers, and undoubtedly their small numbers, make their image among the weaving population a sorry one, and they prefer to follow a policy of withdrawal and criticism rather than anything more active. They condemn the trends visible at Barawafat and curs (the anniversaries of Muslim shrines, literally the reunion of the soul with God), characterizing it as the tendency of lower-class, illiterate people to go astray. Such criticism is freely voiced in private conversations, for example, but never publicized in the main Urdu newspaper, Qaumi[*] Morcha[*] , which happens to be Deobandi, because, in the words of a poor weaver, "it needs readers."

At another level, among those who would celebrate Barawafat, there are crucial differences between Sunnis and Shias. In the Sunni version: "The Shias believe it is wrong to be happy. And Sunnis cannot accept

that all you must have is lamenting and self-abnegation." "Victory" for either side lies in a demonstration of their preferred way through a celebratory mode. Sunnis are far more numerous in Banaras than Shias, who are estimated at perhaps five hundred houses, and would have no trouble in having their way, except that Dalmandi, the center of Barawafat celebration, is also the nucleus of Shia residence. So police mediation is required, and according to entries in their Festival Registers, "There should be careful duty at Shias' homes. Anjumans should not be allowed to sing those songs near there which may be considered anti-Shia" (Chauk TFR).

Finally, there is a separation of classes within the Muslims such as has been mentioned in the case of c Id[*] and Baqr c Id, which is very explicit at Barawafat. Wahabis and the reform-minded are not restricted to the upper classes, but most of them do seem to belong to the business and trading families. It is difficult to be precise in the absence of statistics on the subject, especially as those who favor a stricter Islam do not always make their views very public, but the opinion of most ordinary weavers, as well as the educated and politically conscious among them, is that the "bigger" people are also those who are very particular about observing only the canonically correct Islamic occasions. The committees formed for fund collection and decoration at Barawafat are all drawn from the ranks of ordinary weavers, dyers, printers, designers, sari embroiderers, and petty shopkeepers. The needs of a particular muhalla[*] range between Rs. 2,000 and Rs. 20,000, satisfied mainly by individual donations of, usually, two to five rupees each. The bigger people in the muhalla are also obliged to contribute, but they neither participate in the activities nor are expected to. The "diases," consisting of judges, honored guests, trophies, and gifts are produced by yet other committees, which generate funds from donations for prizes and decorations.

All this mobilization is the result of shauk , intense love for an activity for its own sake. Shauk itself was not class-bound in Banaras in the past, but as I have shown at length elsewhere (Kumar 1988), it is progressively becoming a quality that characterizes the poor rather than the rich. With change in the cultural role of upper-class patrons, indeed a withdrawal on the part of the elite from the city's traditional cultural life, shauk is not something that the prosperous and educated boast of any longer, with the exception of a few older, clearly old-fashioned, partially eccentric members of the traditional elite. The typically Banarsi pleasures of public organization for poetry, music, inter-muhalla competition, mela decoration, and festivals are significantly characterized as "idleness," "ignorance," and "backwardness" by the rich and sophisticated, and as "shauk" by the poor.

The Weaver as Banarsi

One aspect of Muslim religious practice that I have intentionally excluded from discussion above is the practice of visiting mazar s[*] , the tombs of pir s (saints) and shahid s[*] (martyrs). There are some thirty important mazar s in Banaras which most Muslims would recognize and a few dozen more of local importance to muhalla s[*] . They each have a special day of the week for visits, and an annual curs celebration, the death anniversary of the man entombed (popularly believed to be resident) in the shrine. These shrines are a potent force in the minds of devotees, and also the homes of dear and familiar figures. As sources of power they are not given recognition by Muslim religious leaders, and they have found no avenue of assimilation into orthodoxy. This last fact aside—for in Hinduism the distinction between "classical" and "folk" religion is neither clear-cut nor real—the practice of visiting shrines and the celebration of curs in particular is parallel to the Hindu popular practice of worship at local shrines. The term mazar[ *] is itself etymologically related to ziyarat[*] , "having the vision of," thus making the purpose of shrine visitation comparable to darshan . What especially concerns us here is the development of curs . Like the annual celebrations at Hindu temples, called shringar s[*] , curs have been expanding in recent years in number, multiplicity of locales, sound, dazzle, and effect.

There is an orthodox way of celebrating the curs : the grave is bathed and sprinkled with rose water and perfume, and old covers are replaced by new ones. Halqa[*] (calling out the name of Allah), qurankhani[*] (reading the Quran), tabarrukh (the offering and distribution of food), fatiha[*] (praying), nat[*] and qawwali[*] (verses set to music) are accompanying sanctioned activities. The patron of the curs , as we know from the details in the Festival Registers of each police station (see Kumar 1985), is traditionally one of the devotees willing and able to finance the whole affair. In both shringar s and curs , there is one major pattern of change over the last fifty years: their number seems to be increasing manifold (see chapter 4, this volume, for related discussion). Every deity and shrine must always have its anniversary, thus "increase" means that the annual celebrations are more noticeable now: bigger, brighter, louder, and far more public than before. The new style of celebration that has evolved has taken the following form: a team of professional musicians is invited to perform late at night, usually at midnight. A public stage is set up with lights, frills, flowers, and so on, and the street in front is turned into an auditorium with cotton rugs, tents in some cases, and plenty of loudspeakers. An audience collects for the show, which goes on most of the night. The most popular program consists of qawwali[*] at curs , and at the comparable shringar[*] celebrations, of qawwali and biraha[*] (for the latter see chapter 3, this volume).

This form of celebration dates back no more than twenty-five to thirty years. Its evolution may be documented from oral sources of three kinds: the polemics of maulavi[*] and maulana[*] ; the testimony of older weavers; and, most significant, the accounts of musicians. Sources of accounts are men such as Bismillah Khan, who has performed in every temple and shrine in Banaras; Chand Putli, the most popular qawwal[*] in Banaras today; and Majid Bharati, perhaps the second most popular qawwal , who contrasts his popularity with that of his teacher, Rafiq Anwar, over thirty years ago. These performers can describe in graphic detail how tastes have evolved and the world of popular culture in Banaras has expanded. The religious leaders are critical of shringar s[*] and curs , regarding the latter as imitations of the former, and as evidence of the unfortunate ignorance and backwardness of the weavers and of their tendency toward lower-class behavior. Shringar s[*] and curs , to my mind, are indicative of a "lower class" identity, in that they serve to separate and define their participants. Not only are the funds again collected totally by donation within the neighborhood, the event is considered to be one belonging to the nich[*] qaum , chote[*]log (lower orders, small people) and garib (the poor). There is no educated, well-off person, including those who enjoy ghazal and qawwali[*] otherwise, who would acknowledge enjoying the music and all-night festivity of the shringar[*] or curs , or who would consider the celebration to be his in any way.

The conflict experienced by maulana s[*] and social leaders between an orthodox Islamic practice and local "distortions" is not shared by participants themselves. The weaver of Banaras claims an "Islamic" identity, and considers his veneration of pir s, babas, and shahid s an important part of his faith. There is no experiential problem of "adjustment," as is spoken of in other parts of South Asia, of an Islamic identity with a territorial-cultural one that is heavily oriented toward local Hinduism (Ellickson 1976, Fruzzetti 1981, Madan 1981). The observer's temptation to claim imitation or adjustment of an ideal to a local version is strong, but not necessarily appropriate.

As with the style of celebrations, the process of identity formation derives from a cultural fund common to both Hindus and Muslims. In the case of celebratory styles, for instance, there is a common response to certain sensory forms: lights, loud sound, crowds, openness, all-night participation. In the case of identity, there is a way of emphasizing the local, the immediate, and the contextual (the "traditional," the "way of the place") that prompts me to make a case for the weaver as "Banarsi."

The emphasis, that is, should be placed on the elements shared by these artisans. The Muslim weaver of Banaras is as shaukin[*] (characterized by shauk , passion and taste) a man as the Hindu metalworker and milk seller, and central to his lifestyle is the love of the outside, of akhara s[*] for wrestling and body building, for music and poetry, and of

the city itself. He has different occasions and locations around which his activities are structured: he will prefer to go to Chunar and to Rajghat, to the mazar s[*] of Shah Washil and Chandan Shahid, whereas the metalworker will go to the Devi temple in Vindyachal. Both Hindu and Muslim artisans agree that Chaitra (March–April) is the best "season" for going on outdoor trips. While both share an attitude of passion for the freshness and openness that constitutes the outside, a commitment to the freedom to be able to go when they please, and a sensitivity to seasonal and geographical variations, the difference in their attitudes is that in the Hindu case, the popular version of "the good life" has sanction from religion, while for Muslims it explicitly does not. Those at the top of the Hindu hierarchy—pandit, sadhu, raja, rais , politician, businessman, and otherwise important or respected men—will always be thought the better of for being appreciative of bhang, darshan , and the outside (see Kumar 1986). In the Muslim case, the maulana[*], maulvi[*], sardar[*] , social leader, rich businessman, find the pleasures of the ordinary weaver only something to denigrate. Correspondingly, while Hindus feel that entertainment, religion, natural beauty, God's presence, all do and should coincide, a Muslim does not make explicit connection between a religious mela and the beauty of the season. The largest festivals—c Id[*] , Baqr c Id, Holi, and Diwali—are all celebrated with outdoor trips. The ideas of Hindus and Muslims regarding space and time coincide. The ideas of Hindus draw from many different sources, including medical lore and the teaching of the sages. Those of Muslims are thoroughly Banarsi, with no support in Islamic teaching or tradition.

Many other favorite activities may be discussed to support the claim of a common lifestyle and expression of Banarsipan[*] (Banaras-ness) for both Hindus and Muslims. Both are articulate about their love for music and poetry, especially as performed and produced by themselves. Artisans of all castes and communal affiliations meet regularly in informal groups to sing and recite. They organize the shringar s[*] and curs already discussed, and music and verse underlie the attractiveness of major festivals such as Barawafat and Holi. Or one could talk at length of the importance of akhara s[*] , such as Amba Shah ka Taqiya in Madanpura, where local boys work out every morning and evening, and informal wrestling competitions are held every Sunday, attracting members from akhara s all over Banaras. Equally indicative of a common popular culture is the art of sword and lathi wielding, taught in some one hundred Hindu and Muslim akhara s all over the city, distinguishable from each other only on the basis of their expertise, not religion. These akhara s are informal clubs, organized into two "federations," that of "the fifty-two" and that of "the eighty-two" (bavani[*] and bayasi[*] ), both called panchayats and united under an umbrella organization called the Bharatiya[*] Shastra[*] Kala[*] Parishad (Indian Association for the Art of

Weapons). Each akhara[*] has its own flag, ustad, and "office," and the members of these perform under their respective banners at Muharram, Nakkatayya, Durga Puja, and other assorted Hindu and Muslim processions.

A large part of the identification of weavers with Banaras comes from their understanding of the city itself. Both the terms "Banaras" and "Banarsi" have a Hindu ring to them, and in fact the Hindu imagery in the city is quite awesome. Muslims have some techniques to keep themselves from being overawed. While recognizing the centrality of Banaras for Hinduism and the sacredness of the Ganges as an "objective" fact, the Muslims of Banaras treat it as an important Islamic center. The older mosques of Banaras, Arhai[*] Kangura[*] , Ganj-e-Shahida[*] , and Abdul Razzaq[*] Shah[*] , are regarded as evidence of the age of the Muslim presence in the city. The tombs of Lal[*] Khan[*] , Fakrud-din[*] , and Ghazi[*] Mian[*] , among many others, are seen as testimony to the legitimacy of Muslims, having supposedly arrived with the very first waves of conquest and conversion in northern India. Since their craft, in this version, dates from that time, there is no better confirmation of their share in the city's culture than the existence of old mosques and tombs, practically in every muhalla[*] bearing witness to their age and numerical strength. Among later mosques, those that date from Aurangzeb's time, such as the Gyan[*] Vapi[*] , the Lat[*] , and the Dharhara[*] , are regarded with special pride, and are indeed imposing architectural artifacts (Sen 1912:71–80). From the minarets of Gyan Vapi, Razzaq Shah, and Dharhara, the whole city may be swept in one glance, that is, visually controlled. Besides these more formal landscape markers are the myriads of shrines to beloved teachers and respected men, the scenes of weekly visits, seasonal melas, and annual curs , and the centers of everyday life. All these geographical devices create a sense of a "Muslim" history of Banaras, rendering the place no longer "Hindu" or alien, but open, friendly, and benedictory. Most Hindus, of course, are ignorant or indifferent to the Muslim perspective on the history and geography of the city (as are most scholars, including those in this volume; see Kumar 1987) and do not question why Muslims feel so much at home in Banaras. Muslims regard themselves for most purposes as residents of particular wards and muhalla s[*] , but share this overall perspective on the large whole of the city without perhaps demonstrating it in a comparable way.

Given the strength of the arguments in favor of a Banarsi identity, the question of Hindu-Muslim conflicts in Banaras becomes a particularly pertinent one. It is far larger than may be resolved with the scope of this chapter. By 1885, the beginning of our period of study, Hindu-Muslim conflict on various occasions was already an accepted phenomenon on the north Indian stage, and for the next four decades,

until 1930, there is reporting in Banaras newspapers of riots in the rest of the province. No riots occurred in Banaras during this period, but the reiteration of this very fact began to seem ominous. The first riot in more than a hundred years took place in 1931 and is retained in public memory as the turning point in a stretch of extraordinary social relations. Since 1947, a peaceful year for Banaras by all-Indian standards, there have been perhaps half a dozen incidents necessitating police action (Aj ; Thana Registers). At none of them, including the last one I witnessed in February 1986, does the situation become "tense" for the whole city. There are well-delineated places, routes, and crossings that are fields of tension, and these relive a drama every year in a local way. The total number of these have not expanded in any proportion to the increase in the number of processions, the increase in the population itself, and the multiplication of amateur "politicians"—local leaders alive to the dynamics of petitioning, agitating, and seeking any possible base for arousing a following. Peace is difficult to measure, and disturbances are not, but by any criteria most of the neighborhoods of Banaras are free of regular, annual, or even rarer tension. And by the common assent of poor weavers, prosperous firm owners, and all Hindu classes, the nature of Hindu-Muslim relations in the city is exceptional—given the fact that "Hindu" and "Muslim" are already politicized identities.

Many scholars (see Freitag, Introduction) consider this to be attributable to the existence of a culturally homogeneous, "Hinduized" style of leadership in the city, with a tradition of political, antigovernment agitation rather than communal strife (see also Bayly 1975, 1978; Freitag 1980). While leadership is certainly a factor, I tend to consider it less important than the complex nature of popular consciousness in the city. This consciousness is well rooted in economic life. What is usually cited in this connection is the fact that Hindus and Muslims are totally interdependent within the silk industry, most obviously in the relationship of purchaser and supplier. The majority of silk merchants are Hindus, and almost all weavers are Muslims. This contributes to harmony, not conflict, although given the exploitation by merchants, it may also be regarded as a desperate kind of harmony. There have been occasions when weavers refused to participate in a communal quarrel of larger provincial dimensions because "our rozi-roti[*] (livelihood) depends on the Hindus" (Bharat Jiwan , 27 May 1907, 8). Weavers have also been known to exercise leverage on the merchants because of the latter's dependence on them, as in the Burhwa Mangal incident mentioned earlier.

This interdependence is of limited influence, it seems clear, in that there are plenty of Muslim merchants and middlemen, and their mu-

tual relations with weavers are different in no respect from those of their Hindu counterparts. Similarly, the other dozen or so artisans who are all Hindus experience no different relations with the traders and shopkeepers in their respective industries. What seems more influential in promoting harmony is the fact of artisan occupation itself. Hindus and Muslims of lower classes share a similar lifestyle and ideology of work, leisure, and public activity. And while that of the upper classes has changed over the last century, that of the lower classes has remained substantially the same. This parallelism in lifestyle and sharing of popular culture, drawing inspiration as it does from separate religious ideologies as well as a common cultural fund, is not coincidental or trivial. It is not self-evident that the actions of Hindus and Muslims should be interpreted more from the perspective of political leadership or religious revivalist and reformist movements than in the light of their own experience based on their culture of everyday life.

Conclusion

My analysis of identity has been strictly on the work and leisure patterns of ordinary weavers, and has revealed a cultural system that is not divided primarily into categories of religion or community. Equally defining influences on this cultural system are occupation and urban tradition. The weaver as artisan confronts certain dimensions within which his life necessarily revolves: those of poverty and insecurity and the attendant problem of illiteracy. Yet all poor people are not identical, and the artisan has a peculiar assessment of his skill and worth, and a way of asserting his right over his freedom that is surprising in its aggressiveness. We may feel we have understood the matter, and are also willing to loosen our imaginations to further accept the fact that with a harsh and demanding life go a love of leisure and an elaboration of the festival calendar. A more detailed investigation, however, reveals a richness of practice and a level of articulation that are not too familiar in social science literature. Most striking of all is the discovery of the influence of local tradition and the love of one's place, the importance of the city and the very neighborhood in deciding how one is to view oneself. That all this should be recognized as an integral part of identity is not generally accepted.

My effort has been partly to show the importance of everyday practices of work and leisure, and the close relation of popular culture and identity. The identity of the weaver in Banaras is neither simply "communal," that is to say, religious, nor is it progressively becoming so. It has a vision of Islam, but one that splits up the Muslim population along different lines. Nor is it exclusively occupational, the mean-

ing of which we may prejudge from a knowledge of the work performed, though the most powerful determinants on the weaver remain the economic ones. Finally, the identity is "Banarsi," not in the sense of being imitative of a Hindu Banarsi tradition, but drawing largely from the same roots as do the Hindus, that is, those testifying to the importance of locality and continuity with the past.