PIETY, PATIENTS, AND PASSIONS OF THE MIND

It was early believed that pathological phenomena, such as a state of anxiety, might be a consequence of sin. Metaphysical causes were considered as well: a punishment by God or retribution of debt, which brought the patient into a situation that he needed the assistance of the Church. These interactions between the physical and the metaphysical, between the mind and the body, belonged foremost to the field of moral theology.[8] Doctors were only permitted to give their opinion on the

[6] An impressive study of this problem can be found in Michael MacDonald, Mystical Bedlam: Madness, Anxiety, and Healing in Seventeenth-Century England (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981).

[7] Jean Torlais, "I'Académie de la Rochelle et la diffusion des sciences au XVIII siècle," Revue des sciences 12 (1959): 111-135.

[8] G. S. Rousseau, "Psychology," in The Ferment of Knowledge: Studies in the Historiography of Eighteenth-Century Science, ed. G. S. Rousseau and Roy Porter (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1980), 175. Rousseau wisely pays attention to religious treatises on the soul by English clergymen, adapted by physicians. The French school of historians (especially Annales and the social historians) has been very active in their search for traces of fear in last wills and prayers; see for instance Jean Delumeau in La pent en occident, XVIe au XVIIIe siècle (Paris, 1978).

temper of the patient; they were not free to venture upon the psychological analysis of his fear.[9] It would be fruitless to search medical treatises for such psychological evaluation. Instead of analysis, doctors were trained to substantiate evidence on the four tempers, the choleric, melancholic, phlegmatic, and sanguine temper, and to respond to the predisposition of patients for emotional reactions such as fear. They explained the physiology and pathophysiology of these emotional reactions, they described various case histories, but they refrained from explaining the "spiritual fears," in terms of guilt and remorse.

The pious had a different attitude in the acceptance of the emotionally disturbed patients, different in that they invoked religious agents as antecedent to physiological causes. They did not neglect anatomy or physiology: they rather blended the two into an original pietistic model.[10] This was especially true in Halle, Germany, where Pietism was the leading religion. Michael Alberti (1682-1757) rejected any materialistic explanation of disease, certainly for disease in which the mind was involved. Alberti was the son of a pietist minister. After studying theology and afterwards medicine, he became a devoted pupil of Georg Ernst Stahl (1659-1734), the leading professor of medicine in Halle. Alberti's Specimen Medicinae Theologicae (1726) was an attack against the Cartesian concepts of Friedrich Hoffmann (1660-1742), who discussed the passions of the mind in his Medicina Rationalis Systematica (1716). In the Netherlands, physicotheology became an important field of interest of enlightened Protestantism. It allowed ratio et experientia as a tool for searching the causes of natural phenomena, for emotional disturbances as well as for other diseases.[11] So it is likely that we find more open discussions of the emotions in medical treatises written in the Netherlands at the time of Herman Boerhaave (1668-1738) and Hieronymus David Gaub (1705-1780). The differences between the Leiden and Halle Schools will be discussed later in this essay.

[9] K. Rothschuh, Konzepte der Medizin in der Vergangenheit und Gegenwart (Stuttgart: Hippokrates Verlag, 1978), 67-70.

[10] Rothschuh, Konzepte. An excellent discussion on the attitude of the patient in pietistic centers in Germany has been given by Johanna Geyer-Kordesch, "Cultural Habits of Illness: The Enlightened and the Pious in Eighteenth-Century Germany," in Patients and Practitioners: Lay Perceptions of Medicine in Pre-industrial Society, ed. Roy Porter (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986), 177-204.

[11] J. Bots, Tussen Descartes en Darwin: Geloof en Natuurweteuschap in de achttiende eeuw in Nederland (Assen and Amsterdam, 1972), especially 49-60; J. van den Berg, "Theologie-beoefening te Franeker en te Leiden in de achttiende eeuw," It Beaken: Tydskrift fan de Fryske Akademy 47 (1965): 181-191.

Fear is one of the most important passions of the mind, as the great novelist quoted in the epigraph intuited at mid-century. These passiones animi were a subject of study for philosophers from Aristotle onward, who reduced all passions to pleasure and pain.[12] The philosophers of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries paid sufficient attention to the emotions and their interaction with the body in order to bring these phenomena into agreement with the new philosophy of René Descartes and the discoveries in anatomy and physiology.[13] This newfound classical series of passions attached to pain and pleasure were ira (wrath), terror (fright), metus (fear), moeror (grief), pudor (timidity), spes (hope), gaudium (joy), and amor (love). These passions, like the group of six non-naturals, were most popular in medical literature and had been described by Galen.[14] The nine passions received more attention in the course of the eighteenth century, especially through the contribution of Arnulfe d'Aumont in the Encydopédie of Diderot on health and hygiene.[15] A well-balanced mind was important, not only for the pious and the patients but also for the politicians, to keep the people peaceful and in a state of mental health. Although medical students were primarily engaged in the physical bodily changes accompanying the passions, they referred to John Locke's An Essay concerning Human Understanding (1690)[16] and to Hume's A Treatise of Human Nature (1739), the chapter " On the Passions," for their philosophical backgrounds and understanding of fear. Neither author believed in an inborn ability to reason but accepted experience by way of the external senses at the main source of knowledge. For Hume (1711-1769), the passions were sense perception intercepted by its idea.[17] Hume considered fear a direct passion, an

[12] L. J. Rather, "Old and New Views of the Emotions and Bodily Changes: Wright and Harvey versus Descartes, James and Cannon," Clio Medica 1 (1965): 1-25.

[13] Ibid. Descartes's Les passions de l'âme was translated into Dutch in 1659 by J. L. Glazemaker.

[14] Air, motion and rest, food and drink, sleep and watch, evacuation and retention, and the passions of the mind. For a contemporary definition see John Harris, Lexicon Technicum, or, An universal English Dictionary of Arts and Sciences: explaining not only the Terms of Art, but the Arts Themselves (London, 1736). He describes them as the Non-Natural Things, or the Non-Natural Causes of Diseases. See n. 15.

[15] William Coleman, "Health and Hygiene in the Encyclopédie: A Medical Doctrine for the Bourgeoisie," Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 29 (1974): 399-421. See also L. J. Rather, "The Six Things Non-Natural: A Note on the Original Fate of a Doctrine and a Phrase," Clio Medica 4 (1968): 337-347.

[16] Sylvana Tomaselli, "Descartes, Locke and the Mind/Body Dualism," History of Science 22 (1984): 185-205.

[17] David Hume, A treatise of human nature, being an attempt to introduce the experimental Method of Reasoning into Moral Subjects, vol. a, Of the Passions (London, 1739).

impression that arises immediately from good or evil, from pain or pleasure.[18] He also attached great value to the power of imagination in this passage from the perception of the virtue or vice to the impression he considered almost identical with the passion. Furthermore, Hume used the term "probability" to change a passion:

Throw in a superior degree of probability to the side of griet, you immediately see that the passion diffuses itself over the composition, and tinctures it into fear. Encrease the probability and by that means the grief, the fear prevails still more and more, till at last it runs insensibly, as the joy continually diminishes, into pure grief.[19]

This combination of passions or transitions from one passion into the other was also considered by some medical students from Edinburgh, as we shall see. Combining passions suggested a way of psychological analysis and psychological treatment. Hume's enthusiasm for natural philosophy drove him far so as to compare the passions with optical phenomena:

Are not these as plain proofs, that the passions of fear and hope are mixtures of grief and joy, as in optics it is a proof, that a colour'd ray of the sun passing thro' a prism, is a composition of two others, when as you diminish or increase the quantity of either, you find it prevail proportionally more or less in the composition? I am sure neither natural or moral philosophy admits of stronger proofs.[20]

For the enlightened students, educated by ratio et experientia, this metaphor must have been delightful. It is also interesting to notice that ideas of uncertainty in fear are preeminently present in theories of acting. We shall pay brief attention to the concept of fear as it was used in the theater. An actor had to play his part in such a way that his facial expressions and his gestures could be recognized by a large audience. In effect, there were prescriptions for the interpretation of the passions.

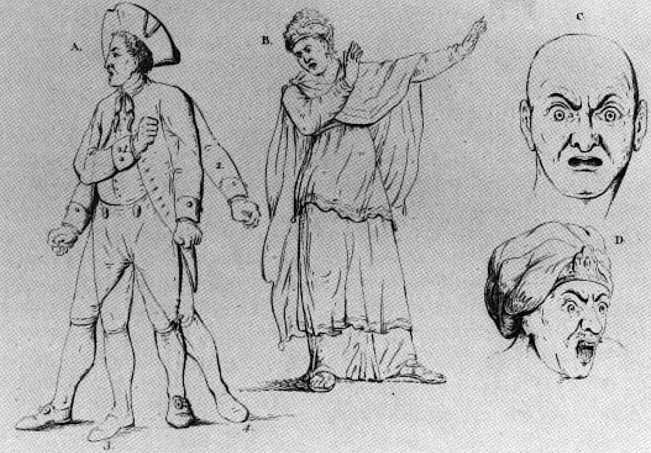

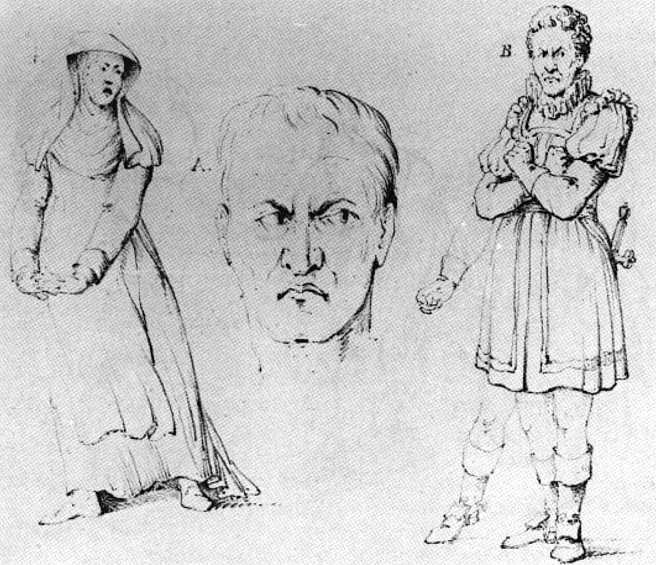

A semblance of fear should be expressed by a shrinking of the body; the actor should stand erect, with his arms along his body and his fists closed. His legs should be slightly apart; his eyes should be flickering with a restless glance. He should pace up and down the stage, twisting his fingers, but at the same time keep his shoulders hugged and he should express the uncertainty in his face.[21] These instructions were

[18] Ibid., 181.

[19] Ibid., 218.

[20] Ibid., 219.

[21] J. Jelgershuis, Theoretische lessen over de gesticulatie en mimiek (Amsterdam: Meyer/Warnars, 1827), 150.

Pl. 6. "Expressions of Fear by Actors," in J. Jelgerhuis, Theoretische lessen over gesticulatie en mimiek (Amsterdam, 1827).

partly inspired by the French painter Charles le Brun (1619-1690), who wrote a manual on the way of illustrating the passions.[22] This booklet influenced several Dutch painters including Gerard de Lairesse (1641-1711), who praised le Bruns's work.[23] But the actors were also indebted to Petrus Camper (1722-1789) and Georges Louis Leclerc de Buffon (1708-1788), who paid attention to the physiognomy of the passions from a medical and a biological point of view. Buffon described with great care the changes of the facial expression in various stages of fear, observing the eyes, the eyebrows, the lips, and the opening of the mouth.[24] Petrus Camper tried to explain these changes anatomically, paying tribute to the innervation of the facial muscles and urging his students to notice the changes in the body in general, when they were

[22] Over de afbeelding der Hartstogten of Middelen, om dezelve volkomen te leeren afteekenen, translated into Dutch by F. Kaarsgieter (Amsterdam, 1703), from the original French version by Charles le Brun, Conférence sur l'expression générale et particulière (Paris, 1698).

[23] Jelgershuis, Theoretische lessen, 130.

[24] Buffon's Histoire naturelle was published between 1749 and 1789. Part of this impressive work is on the natural history of man. In this study, he described the expressions of passions. Histoire naturelle, vol. 20 (Paris, 1799), 177, 183).

Pl. 7. "Expressions of Fear by Actors," in J. Jelgerhuis, Theoretische lessen over gesticulatie en mimiek (Amsterdam, 1827).

describing frightened persons.[25] These facial expressions were also observed by the physicians, who mentioned these signs in their description of the frightened patient. But physicians used a medical interpretation; they were more interested in the physiological explanation of the pale color, the trembling lips, and the shaking knees, than in a lively portrayal of the patients' physionomy. We find these representations in particular in some student dissertations.