1—

A Golden State:

An Introduction

James J. Rawls

On January 24, 1848, a thirty-two-year-old Virginian named Henry William Bigler recorded in his diary one of the most fateful sentences in American history: "This day some kind of mettle was found in the tail race that looks like goald first discovered by James Martial, the Boss of the Mill." Thus was first recorded, in a scrawl barely legible, the momentous discovery of California gold by that eccentric master carpenter James Wilson Marshall working at Sutter's Mill on the South Fork of the American River. As news of the discovery spread across the country and around the world, California was transformed. Hundreds of thousands of Argonauts—a name derived from Jason's followers in search of the Golden Fleece of classical mythology—rushed to what would soon become the Golden State, hoping to find for themselves a for-tone in that precious "mettle." Their coming was the foundational event not only for the economic history of California, but for much of its social, cultural, and political history as well.[1]

For an event of such importance, it is striking that we know so little of the exact circumstances of the discovery itself. Marshall was never entirely sure of the date. He later speculated that he had made the discovery "on or about the 19th of January."[2] Several other accounts, including Bigler's diary entry, contradict Marshall. One dubious version, preserved by historian Hubert Howe Bancroft, takes the credit from Marshall altogether. It casts a Native American mill worker, one "Indian Jim," in the role of discoverer. According to this account, the Indian discovered a nugget "as large as a brass button" that he gave to a white worker, who in turn showed it to Marshall.[3] Such discrepancies should not be surprising. As Rodman Paul reminds us, "the difficulty is that no one anticipated, few witnessed, and fewer still recorded the event . . . . The participants in the gold discovery were simple people who had little education and felt little incentive to keep written records."[4]

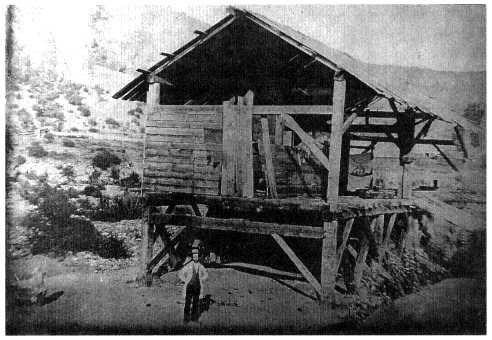

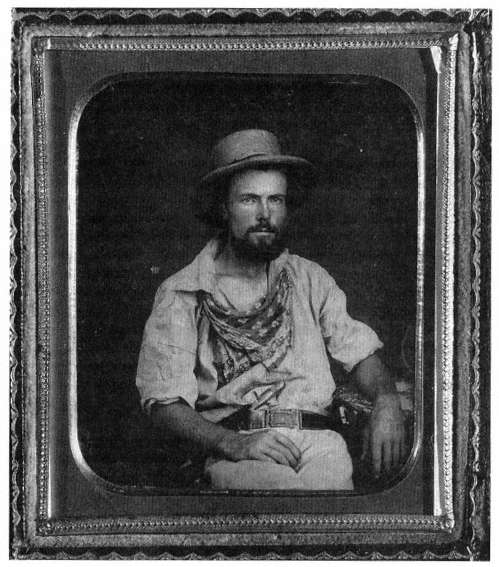

John Sutter's sawmill on the South Fork of the American River, where on a chilly January

morning in 1848 James Marshall caught the glint of gold in the recently deepened tailrace

and, stooping to gather the flakes—none larger than a grain of wheat—changed the course

of history. The figure in the foreground of the daguerreotype, taken by Robert Vance about

1850, is thought to be Marshall. California Historical Society, FN-30892 .

The background of the gold discovery stretches back through geologic time to the very creation of California. According to the theory of plate tectonics, the subduction of the Pacific Plate beneath the western edge of the North American Plate generated enormous heat. Within this molten crucible, metal-rich compounds dissolved into solutions that were injected into fissures of rocks being formed above. Different combinations of minerals precipitated to form deposits of various metals.[5] Thousands of veins of gold thus were created in the granitic core of California's primordial mountains. Over eons, erosion tore loose tiny particles of gold and washed them into rivers and streams, where they lodged on sandbars or behind stones. There the particles lay undisturbed until that portentous day in January 1848.

The first people to live in California may well have known of the gold, but apparently they regarded it with little interest. Those who came later were gold-possessed. Spanish explorers and conquerors were drawn ever onward through the Americas by the lure of tales of magnificent wealth. Somewhere up ahead, they believed, were the fabled Seven Cities of Gold and E1 Dorado, "the Gilded Man," whose loyal subjects

covered him with gold dust every morning and washed it off every night. Even the name "California" was identified with these golden dreams. Before Spaniards discovered this land, García Ordóñez de Montalvo's early sixteenth-century novel Las Sergas de Esplandián described a place that he called California, a mythical island "very near the Terrestrial Paradise" upon which the only metal to be found was gold. In the 1530s, Spaniards gave the name to the region along the coast north and west of Mexico.[6]

Gold in the Americas, of course, was no myth. Gold worth billions of pesos was taken from the mines of Spain's Latin American colonies. Great mining centers boomed at Potosí and Zacatecas, at Huancavélica and Pachuca.[7] Gold was even discovered in Mexican California, in 1842 at Placerita Creek, about thirty-five miles northwest of the pueblo of Los Angeles. Although gold from the Placerita strike was the first ever sent from California to the U.S. mint, the deposits proved to be inconsequential and attracted little attention. In one of the great ironies in American history, Marshall's discovery came within days of the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo on February 2, 1848. Mexico thereby ceded sovereignty to about half its national territory, including gold-rich California, just as the value of that territory was poised to appreciate enormously.

Like ripples in a pond pulsing outward from a skipping stone, the news of Marshall's discovery circled the globe. Everywhere the reception of the news followed a similar pattern. At first, reasonable people responded with incredulity. Reports of nuggets as large as misshapen billiard balls and hens' eggs were dismissed as tall tales. How could there possibly be as much gold in California as such wild rumors suggested? Only as the rumors were confirmed by subsequent reports did reasonable people find themselves possessed by a gold mania. Their intense excitement was compounded by a determination to make up for the time they had lost in doubt.[8]

News of the discovery first appeared in March in San Francisco's two fledgling newspapers, the Californian and the California Star . But the reports failed to stir any immediate excitement. Monterey resident James H. Carson later recalled that during April and May a few local inhabitants left for the mines, but only after having "put the whole golden report down as 'dod drat' humbug." Carson remained an "unbeliever" until May 10, when he saw with his own eyes a sack of gold nuggets, some truly as large as hens' eggs. Then came the moment of Carson's conversion. "There was before me proof positive that I had held too long to the wrong side of the question." His description of what happened next is a classic account of the contagion that began raging out of control:

I looked on for a moment; a frenzy seized my soul; unbidden my legs performed some entirely new movements of Polka steps—I took several—houses were too small for me to stay in; I was soon in the street in search of necessary outfits; piles of gold rose up before me at every step; castles of marble, dazzling the eye with their rich appliances;

"You'd have to be turkey to believe such ducks!" runs the caption beneath a cartoon in the

April 12, 1849 issue of the Parisian paper Le Charivari , making a lively play on the word

canards—literally "ducks," but colloquially "a false report" or "hoax," especially as

circulated by the press. Despite the well-intentioned skepticism of the artist, thousands of

Frenchmen purchased stock in gold mining companies, at five francs a share or more, and

countless others made the voyage themselves. In 1853 a San Francisco journal claimed that

over thirty thousand Frenchmen resided in the Golden State. California Historical Society,

FN-30966 .

thousands of slaves, bowing to my beck and call; myriads of fair virgins contending with each other for my love, were among the fancies of my fevered imagination. The Rothschilds, Girards and Astors appeared to me but poor people; in short, I had a very violent attack of the Gold Fever.[9]

The promise of great wealth, obtained quickly and easily, had a universal appeal. Few could resist its allure. In a phrase made famous by historian J. S. Holliday, "the world rushed in," and California soon became home to the nation's most ethnically diverse population. Included among the gold diggers were Native Americans, working either as laborers for white miners or as independent agents. Colonel Richard B. Mason reported in August 1848 that of the four thousand miners then at work in the gold fields, more than haft were Indians.[10] Spanish-speaking Californios also joined the rush for gold, often taking with them Indian laborers from their ranchos. Historian Leonard Pitt has estimated that in 1848 about 1,300 Californios were actively looking for gold.[11] Thousands of other Latin Americans came north to the mines from Mexico, Peru, and Chile.[12] By 1850 the Mexican population in the Southern Mines—in Calaveras, Tuolumne, and Mariposa counties—was about 15,000.[13] From the west came gold seekers from the Pacific Islands and Asia. Place-names such as Kanaka Creek in Sierra County and Trinity County's Kanaka Bar remind us also of the early presence of Hawaiians in the gold country.[14] Australians settled in camps throughout the diggings and formed in San Francisco a loosely knit community known as "Sydney Town."[15] Chinese sojourners, numbering 25,000 in 1852, represented a tenth of the state's non-Indian population; in some mining counties nearly one out of three residents was Chinese.[16] Hundreds of thousands of other Argonauts came from Europe and from the eastern United States. Among these, by the late 1850s, had come 2,500 African Americans, including individuals enslaved and free.[17] "Everybody, speaking all the languages of the world, it seemed, had come in search of gold."[18]

From whatever direction the Argonauts came, they faced enormous difficulties getting to California. Those from the eastern United States followed three main routes to the gold fields. Sea routes were the most popular at first. Sailing around Cape Horn was a voyage of 18,000 nautical miles and took five to eight months. Violent storms off the Cape posed a constant danger to even the most experienced mariners; the fierce gales, recalled one seaborne Argonaut, "produce long, huge swells, over which the ship mounts with a roll, then plunges into the abyss again as if never to rise."[19] Sailing to Central America and crossing the Panamanian isthmus considerably reduced the travel time but exposed travelers to the risk of contracting malaria, yellow fever, and other tropical diseases. Ultimately most California-bound Argonauts traveled by various overland routes through the American heartland. This journey of 2,000 miles took at least three or four months and meant crossing incredibly difficult terrain.[20] Young Sallie Hester, traveling overland with her parents

Bolts of lightning split the dark, roiling clouds over the Great Plains in a drawing by J.

Goldsborough Bruff, captain of the Washington City Company, which departed the

Missouri frontier for E1 Dorado in late spring of 1849. Several miles past the Platte River

a tremendous storm broke over the wagon train, with rain soon turning to hail as the

temperature plummeted forty degrees. "Hail-stones of extraordinary size," wrote Bruff,

"not only cut and bruised the men, whose faces and hands were bleeding, but [they] also

cut the mules." Courtesy Huntington Library, San Marino, Calif .

in 1849, recorded in her diary the rigors of making it across the unbroken deserts of the Southwest: "The weary, weary tramp of men and beasts, worn out with heat and famished for water, will never be erased from my memory.[21] The biggest killer on the overland trail was disease, responsible for nine out of every ten deaths. Cholera was by far the greatest scourge, but scurvy, typhoid fever, and dysentery also took their toll. Drownings while fording swollen rivers contributed to the mortality rate, as did fatal accidents caused by the careless or reckless use of firearms.[22] Following the accidental death of a ten-year-old boy, Lucia Williams wrote to her mother that "for many days we could not forget this agonizing experience. It hung over us like a black shadow. It took all the joy out of our lives.[23]

Arriving in California brought expressions of relief from those who survived the journey. Charles Glass Gray, a young Forty-niner from New Jersey, celebrated his arrival in San Francisco by sleeping in a bed for the first time in seven months. In his

diary he wrote that he was relieved to be off the trail at last, "for I have suffer'd enough already I think."[24]

Was the trip worth it? Between 1848 and 1854, the peak year of production, the Argonauts harvested nearly $350 million in gold from California.[25] The average daily take was $20 per miner in 1848, at a time when skilled artisans in the eastern United States were earning a daily wage of $1.50 for twelve hours of work.[26] But the cost of living in California was far higher than in the East. A loaf of bread that sold for five cents on the Atlantic seaboard cost fifty to seventy-five cents in California.[27] An entire dinner at a New York restaurant could be had for a quarter or a half-dollar in 1849; the bill of fare in a contemporary eatery in San Francisco listed a leg of mutton for $1.25 and "Fresh California Eggs" at $1.00 apiece.[28] More discouraging still was the shifting ratio between the number of gold seekers and the amount of gold being found. By the end of 1848 about 6,000 miners had obtained $10 million worth of gold. Three years later the output was more than $80 million, but the number of miners had swelled to 100,000.[29] Those who prospered in the Gold Rush—men like Levi Strauss, Domingo Ghirardelli, John Studebaker, and Philip Danforth Armour—were entrepreneurs who learned well the axiom that the main chance for success lay not in mining gold but in mining the miners.

One of the most acute observers of the Gold Rush was Louise Amelia Knapp Smith Clappe, author of The Shirley Letters , written along the Feather River in 1851 and 1852. "Gold mining is Nature's great lottery scheme," she wrote on April 10, 1852. "A man may work in a claim for many months, and be poorer at the end of the time than when he commenced; or he may 'take out' thousands in a few hours. It is a mere matter of chance. . . . And yet, I cannot help remarking, that almost all with whom we are acquainted seem to have lost."[30] Historian Oscar Lewis has estimated that fewer than one out of twenty California gold seekers returned home richer than when they left.[31] The frustration of those who failed found expression in the names of their ramshackle mining camps, places like Poverty Hill, Skunk Gulch, and Hell's Delight.[32] Among the many plaintive gold-rush ballads was "The Lousy Miner," first published in John A. Stone's Original California Songster (1855).[33] The opening stanza sets us straight:

It's four long years since I reached this land,

In search of gold among the rocks and sand;

And yet I'm poor when the truth is told,

I'm a lousy miner,

I'm a lousy miner in search of shining gold.

And the final refrain is one of bitter disappointment:

Oh, land of gold, you did me deceive,

And I intend in thee my bones to leave;

William Redmond Ryan, an English-born artist who mined for a spell in the autumn of '48, caught the

labor of his fellow fortune hunters along the Stanislaus River in a drawing that appeared in his

Personal Adventures in Upper and Lower California, in 1848-9 , published in London in 1850. Rich

though the diggings were, Ryan seldom washed more than four to six dollars a day, and, soon tiring

of the hard labor and the "oppressive and injurious" dampness of the river canyon, he turned his

back on the mines and took himself to Monterey. California Historical Society, FN-30974 .

So farewell, home, now my friends grow cold,

I'm a lousy miner,

I'm a lousy miner in search of shining gold.

Frustrated ambitions were vented in an almost unending round of ethnic hostilities on the California mining frontier. Scapegoats were eagerly sought, identified with lightning speed, and dispatched with little regret. The antagonism between white miners and California Indians was especially intense. Whites advocated and carried out a program of genocide that they called "extermination," and in the process thousands of California Indians were killed.[34] San Francisco's Alta California reported in April 1849 that the white miners were "becoming impressed with the belief that it will be absolutely necessary to exterminate the savages before they can labor much longer in the mines with security."[35] Three years later a miner in the

Auburn area reported that mining activity there had been suspended because of Indian hostilities. The miners organized several armed parties "determined to exterminate these merciless foes, or drive them far from us." After an attack on a nearby Southern Maidu village—in which thirty natives were killed outright and those wounded were knifed to death—the miners resumed their search for gold.[36]

Foreign miners fell victim to xenophobic violence as well as to nativist legislation. Accounts of beatings, floggings, and lynchings of foreign miners appear as a bloody litany throughout the literature of the Gold Rush. Many of the mining codes, adopted in the more than five hundred California mining districts, barred Mexicans, Asians, or other immigrants from staking claims. The California legislature in 1850 enacted a foreign miners' license tax requiring miners who were not citizens of the United States to pay a fee of twenty dollars a month. The tax was aimed primarily at newcomers from Mexico, many of whom were experienced miners and skillful in locating good claims. Thomas Jefferson Green, the author of the tax, once boasted that he could "maintain a better stomach at the killing of a Mexican" than at the crushing of a body louse.[37] The tax, coupled with threats of violence, led to the exodus often thousand Mexican miners from California in the summer of 1850. Two years later the legislature adopted a new foreign miners' license tax, setting the fee at three and later four dollars a month. Subsequent legislation made ineligibility for citizenship the main definition of those to whom the tax applied, ensuring that it would be collected primarily from the Chinese (who were barred by race from becoming naturalized citizens). The tax remained in effect until 1870 and produced nearly a quarter of the state's annual revenue.[38]

Historian Malcolm J. Rohrbough has captured the essence of these events in the simplest terms: "The California Gold Rush was about wealth."[39] It was the expectation of great wealth that drove hundreds of thousands of Argonauts rushing to the gold fields. Their presence led to an economic boom that transformed California in countless ways. The Gold Rush also produced a kind of mass hysteria in which greed predominated and ethnic conflict was all too frequent. Philosopher Josiah Royce, born in the gold-rush town of Grass Valley, recognized the power of the forces set loose: "All our brutal passions were here to have full sweep, and all our moral strength, all our courage, our patience, our docility, and our social skills were to contend with these our passions."[40]

Popular understanding of the Gold Rush has evolved in remarkable ways over the past century and a half. The earliest accounts, of course, were the diaries and letters of the Argonauts themselves. Found here is a familiar trajectory of emotions as the miners pass from hopeful anticipation to the painful acceptance of the harsh realities of life in the diggings. Early published accounts of the Gold Rush often examined themes of myth and reality, expectation and disappointment. See, for example,

The Forty-niner Thomas Drew, one of the thousands of bold, confident young Americans

who rushed west to reap the golden harvest when news of the wonderful discovery first

swept across the land. Courtesy Society of California Pioneers .

William Shaw's Golden Dreams and Waking Realities (1851 ), George Payson's Golden Dreams and Leaden Realities (1853), and the acerbic Hinton Rowan Helper's Land of Gold: Reality Versus Fiction (1855).

Two indispensable guides to the abundance of published and unpublished firsthand accounts are Marlin L. Heckman, Overland on the California Trail, 1846-1859 :

A Bibliography of Manuscript and Printed Travel Narratives (1984) and Gary F. Kurutz, The California Gold Rush: A Descriptive Bibliography (1997). Among the best of these eyewitness narratives is J. S. Holliday's editing of William Swain's diary and letters, published as The World Rushed In: The California Gold Rush Experience (1981). Holliday set himself the task of consulting every available gold-rush diary and letter from 1849 and 1850 to provide the larger context; thus Swain's story is truly emblematic. Within six months of his arrival in California, Swain admitted that his expectations had not been fulfilled. He reported that 90 percent of the miners were downhearted and discouraged as "their bright day-dreams of golden wealth vanish like the dreams of night."[41]

Later memoirs and fictionalized accounts, appearing in the decades after the Gold Rush, tended to view the mining frontier through a romantic haze. Understandably, the aging Argonauts wished to put the best possible spin on their youthful exploits. Bret Harte and other local colorists produced nostalgic tales such as "The Luck of Roaring Camp" and "Tennessee's Partner," which conformed perfectly to the way the grizzled veterans of the Gold Rush preferred to remember those glorious "days of '49."[42] Images of heroic pioneers, stouthearted and triumphant, invariably were in the ascendancy in popular celebrations of gold-rush anniversaries. In 1898 California's Golden Jubilee began on January 24 with a procession through the streets of San Francisco witnessed by a crowd of two hundred thousand. Henry William Bigler, then in his eighty-second year, was thrilled to be among those whom the crowd pressed forward to see.[43] The apotheosis was complete by 1948, when Californians observed the centennial of the gold discovery. Gordon Jenkins and his orchestra recorded a "musical narrative" that unabashedly celebrated the Gold Rush as a part of the national legendry.

There's gold in California,

Gold out California way.

Streets are paved with it,

Fortunes are made with it,

Even golden razors

So you can get shaved with it.

Contributing to the general acclaim was a steady stream of scholarly studies of the gold-rush experience. Among the earliest accounts written by an academically trained historian was Charles Howard Shinn's Mining Camps: A Study in American Frontier Government (1885). Shinn praised the democratic genius of the Argonauts who managed to fashion codes of law and to establish legal institutions in the wilds of the gold country. His sympathies were clearly with the European Americans; to him their meting out of justice was fair and praiseworthy. He elegized the miners' popular tribunals as "the folk-moot of the Sierra."[44] Most scholarly accounts over the

Painted in 1884 by the German American artist Oscar Kunath, The Luck of Roaring Camp

portrays a poignant moment in Bret Harte's story of the same name. Pressing forward in

single file, the rough, bearded miners of the district troop into the rode cabin of the recently

deceased Cherokee Sal to gaze on her orphaned infant, Thomas Luck, neatly tucked into a

candle box. In the years that had passed since Harte first mined the rich vein of local color

and began publication of his popular tales, Americans across the country had increasingly

come to regard the Gold Rush with nostalgia, seeing it as a romantic moment in the westward

course of empire. Courtesy Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Gift of Mrs. Annette

Taussig in memory of her husband, Louis Taussig, 26562 .

next half-century continued to celebrate the Gold Rush and all that it seemed to represent. Only occasionally did a more critical perspective appear, such as Josiah Royce's often reprinted account of California history from 1846 to 1856. First published in 1886, Royce's book, subtitled A Study of American Character , saw in the Gold Rush intimations of "both the true nobility and true weakness of our national character." Royce excoriated Bret Harte for his "perverse romanticism" and unconscionable willingness to sentimentalize the miners' brutal habits. Turning an unflinching gaze upon the lynching of Mexicans and the wholesale murder of California Indians, Royce could only conclude: "All this tale is one of disgrace to our people."[45]

The scholarly study of the Gold Rush took a great leap forward around the time of the centennial. Rodman W. Paul's California Gold: The Beginning of Mining in the Far West (1947) was the first serious attempt to analyze the Gold Rush as an economic enterprise. Paul emphasized the growing complexity of mining organizations and mining technology, and stressed the importance of the California experience for subsequent mining frontiers elsewhere in the nation and world. Like Royce, Paul sought to clear away the "thick haze of romantic legend and mythology [that] has settled over the California mining scene." He ended his account with a plea to understand the Gold Rush in multicultural terms: "In California at least a dozen nationalities and half that number of racial strains made major contributions to the progress of mining, and the great state which flourishes today upon America's western border stands as a lasting monument to the effectiveness of their joint efforts."[46] This same larger perspective informed the other major work of urbane scholarship that appeared at the time of the centennial, John Walton Caughey's Gold Is the Cornerstone (1948), a comprehensive overview of the economic, political, and cultural consequences of the gold discovery. Caughey acknowledged the environmental havoc wreaked by the miners, the appalling record of ethnic discord, and the failure of many Argonauts to strike it rich. "Nevertheless," he concluded, "there are tangible proofs that gold was the touchstone that set California in motion on the course that made her what she is today, and that her gold did things for the West at large and the Pacific basin that otherwise would not have been done for a generation or perhaps at all."[47]

In recent decades scholars have brought to the study of the Gold Rush a host of new questions and new methods of analysis. Social historians, for example, have begun analyzing masses of data from manuscript censuses, tax lists, town directories, and probate records. From these data, historians have extracted information about the age, sex, ethnic origin, occupation, family size, and mobility of the residents of particular towns or communities. Ralph Mann, author of After the Gold Rush: Society in Grass Valley and Nevada City, 1849-1870 (1982), brought the methods of the new social history to the study of two mining camps on the California frontier. Confirming many of the earliest anecdotal accounts, Mann concluded that the miners' prospects for instant wealth were quite dim. The heady days of placer mining may have seemed to represent a great chance for making a fortune, but it was only after industrialization had ended frontier conditions that most miners became solvent. Opportunities for upward mobility thus were less than imagined and perhaps even less than in the older, more established, more economically stable areas of the country.[48]

Other historians have borrowed from literary criticism the technique of content analysis to produce systematic analyses of gold-rush diaries. John Mack Faragher, in Women and Men on the Overland Trail (1979), evaluated fifty diaries according to a set

of predetermined values to determine the importance of gender in the perception and reality of the westering experience. David Rich Lewis, author of a prize-winning 1985 essay in the Western Historical Quarterly , took a similar approach in analyzing forty-four diaries of young men on the trail to California. Lewis concluded that aggression and social conflict were parts of the "core experience" of the Argonauts. John Phillip Reid, in his studies of Law for the Elephant: Property and Social Behavior on the Overland Trail (1980) and Policing the Elephant: Crime, Punishment, and Social Behavior on the Overland Trail (1997), presented a more orderly portrait of the trail, emphasizing the remarkable persistence of law-abiding habits among those who were heading west.[49] Likewise Roger D. McGrath, author of Gunfighters, Highwaymen and Vigilantes: Violence on the Frontier (1984), found that criminal and lawless behavior affected only a few specialized groups.

The role of women in the Gold Rush has attracted a growing number of scholars in recent years.[50] The most comprehensive account is JoAnn Levy's They Saw the Elephant: Women in the California Gold Rush (1990). Levy portrayed women responding vigorously and positively to the challenges of life on the overland trail and in the mining camps. Especially valuable is her portrait of the "working women" of California who engaged in a wide variety of economic enterprises. Freed from the bonds of domesticity, gold-rush women enjoyed a greater freedom than they had known back home.[51] Jacqueline Baker Barnhart, author of The Fair but Frail: Prostitution in San Francisco, 1849-1900 (1986), reexamined one of the most common stereotypical roles of western women. She analyzed the prostitutes of San Francisco not as deviants or victims, but as a group of professional workers. She placed them within the tradition of gold-rush entrepreneurship, noting that most prostitutes came to California seeking economic opportunity and that many were willing to leave lucrative jobs working for others to open businesses of their own.[52]

Much of the most recent scholarship on the Gold Rush has been by practitioners of the "New Western History." Emphasizing the importance of racial and ethnic minorities, the New Western historians have produced a considerable library of monographs and synthetic accounts. The multicultural aspects of the Gold Rush take center stage in such general histories of the West as Patricia Nelson Limericks Legacy of Conquest (1987) and Richard White's "It's Your Misfortune and None of My Own " (1991). More focused on the California experience are Tomás Almaguer, Racial Fault Lines: The Historical Origins of White Supremacy in California (1994) and Lisbeth Haas, Conquests and Historical Identities in California, 1769-1936 (1995)-Typical of the approach of the New Western historians is Albert L. Hurtado's Indian Survival on the California Frontier (1988), a book that focuses not on the process of Indian decline but rather on the adaptation and resistance strategies that permitted a remnant of the native people to survive. For a convenient summary of the latest scholarship, see Peo-

ples of Color in the American West (1994), edited by Sucheng Chan, Douglas Henry Daniels, Mario T. Garcia, and Terry P. Wilson.

The present volume is a collection of essays that focus on the economic aspects of the Gold Rush. Each essay, written with the general reader in mind, offers an overview of a particular topic and provides some sense of the state of recent scholarship. The essays reflect the excitement of new work being done in the field, presenting new directions in interpretation, areas of inquiry, and methods of analysis.

The first essay, Ronald H. Limbaugh's study of gold-rush technology, demonstrates the diverse origins of the mining equipment and methods used by the Argonauts. From around the world, miners brought older technologies that they adapted and modified for use in California. Local hybrids emerged, as did innovations, most notably hydraulic mining and stamp milling, in a process that marked California mining as "a regional variant if not a separate species." Driving this dynamic process was the power of material ambition, "a common trait found in all Argonauts regardless of race, class, or national origin." So it is, according to Limbaugh, that the legacy of the Gold Rush lives on today "in the quest for riches in the form of good jobs, good living, personal fulfillment—the same things California Argonauts sought 150 years ago."

The San Francisco Alta California observed in the autumn of 1851 that "the miners are beginning to discover that they are engaged in a science and a profession, and not in a mere adventure."[53] This prescient observation could serve well as an epigraph for Maureen A. Jung's essay on the rise of corporate enterprise in the Gold Rush. As the Argonauts headed to California, they organized simple partnerships and joint-stock companies. But rapid technological advances in the 1850s—most notably the rise of river, quartz, and hydraulic mining—required far greater capital resources. To meet the growing need for capital, large-scale corporations soon became the dominant form of economic organization, and speculation in mining securities became a regional obsession. The mining corporations played a key role in the economic development of California and the West, but they also had their downside. "Corporate power," Jung reminds us, "won out over individual rights, as insiders manipulated share prices, bilked investors, and drained companies. These activities diverted funds from more productive investments, injured workers' livelihoods, and damaged the economy as a whole."

Daniel Cornford's essay on labor and capital, surveying the rise of corporate organization from the perspective of the miners, complements well the work of Maureen Jung. Cornford's approach reflects the interests of the new social historians, going far beyond the anecdotal testimony of individual miners to analyze basic questions of status and mobility. Acknowledging the pioneering work of Rodman

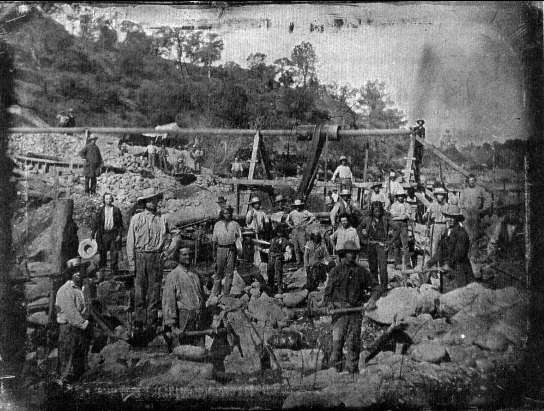

A mining company, which includes several Indians, pauses from its labors to pose for posterity,

probably at Taylorsville, in present-day Plumas County, about 1850. Although the popular image

of the Argonaut is often that of the solitary prospector, the economic imperatives of mining required

gold seekers to labor together relatively early, either in voluntary associations or, increasingly, as

employees of corporate entities. These miners have diverted a stream with a dam and begun their

raid on the auriferous Tertiary gravels beneath the riverbed. Courtesy Huntington Library, San

Marino, Calif .

Paul and the more recent contributions of Ralph Mann, Cornford concludes that upward mobility eluded most Argonauts. The lucky few struck it rich, but the earnings of the average miner "declined sharply from 1848 onward." It is in this context of declining fortunes that Cornford notes the diversity of the gold-rush population and the emergence of ethnic hostilities. He speculates on the origins of xenophobia and racism in the Gold Rush, citing instances of both legal and extra-legal discrimination against immigrant and nonwhite miners. In tracing the development of a labor movement in the California mines, a movement that did not emerge until the ascendancy of hardrock mining in the 1860s, Cornford gives special credit to the role

of Cornish immigrants. He concludes that the "proletarianization" of the California miners reflected the steady decline in their economic position and the consequent growth in social tensions between labor and capital.

Like several other essayists in this volume, Raymond F. Dasmann distances himself from the popular celebrations of "the days of '49" as he begins his account of the environmental changes wrought by the Gold Rush. He notes that the native flora and fauna of California already had been impacted severely by European settlement prior to 1848 and that environmental degradation would have continued even without a Gold Rush. Such was the story of California's grizzlies, sea otters, fur seals, tule elks, and pronghorn, as well as its forests and perennial native grasses. Yet the Gold Rush clearly had an "accelerating effect" on the activities that affected the environment. "It was the Gold Rush," Dasmann observes, "that set off the destructive, furious search for the yellow metal that later brought the moving of mountains and filling of valleys." The tortured landscape left behind stands today as "a monument to greed."

Restraining the passions of the Gold Rush is the topic of Donald J. Pisani's essay on mining and American resource law. His thesis is stated in the opening sentence: "The California Gold Rush profoundly influenced the evolution of property law in the American West." Paralleling Ronald Limbaugh's discussion of adaptive technology, Pisani acknowledges that mining codes did not originate in California but were introduced from many other mining frontiers. Nevertheless, out of the peculiar conditions of California came principles of law that later "became the foundation for mining on the public domain throughout the American West." As conflicts over water usage emerged between miners and farmers, further precedents were established that were adopted in other states. Pisani also notes that the speculative spirit of the miners influenced economic activities generally; the same "obsession with profit" characterized both California mining and agriculture. Raymond Dasmann's perspective on the environment here is reinforced, for Pisani concludes that the Gold Rush "strengthened the assumption that nature existed solely for profit." The legacy of California mining is a mixed one: it "produced great wealth, but it came at a high price."

Duane A. Smith's essay expands the range of California's contributions to the American West and beyond. In the spirit of Rodman Paul's early multiculturalism, Smith demonstrates not only the cosmopolitan origins of California's mining frontier but also its worldwide impact. In addition to technology and mining law, California exported capital, manpower, expertise, and a colorful panorama of mining legends and lore. The influence of California was first seen in Nevada, and later in Colorado, Idaho, Montana, and on mining frontiers around the world. Smith also reminds us that although exports like hydraulic mining devastated the landscape, they also gave rise to powerful counterforces of environmental awareness and protection. From the mining enthusiasms of California came a boisterous materialism and also a legacy of optimism—the notion that "over the next mountain, in the next canyon, would be El Dorado."

Anthony Kirk's interpretive chapter, "Seeing the Elephant," introduces a folio of evocative paintings and drawings of gold-rush scenes, most of them contemporaneous to the events themselves. Many of the images selected by Kirk portray the hardships endured by the Argonauts on their trek to California, as well as the hard times they encountered once in the land of their dreams. Kirk concludes that "few Argonauts gathered the golden harvest they set out so confidently to reap." The sense of excitement and drama present in many of these images is often alloyed with an undertone of bitter disappointment and painful regret.

The next four essays—by David J. St. Clair, Larry Schweikart and Lynne Pierson Doti, Lawrence James Jelinek, and A. C. W. Bethel—consider the impact of the Gold Rush on other contemporary economic activities in California. David St. Clair examines manufacturing and industry, raising the question of whether the Gold Rush had a positive or negative effect on the pace of their development. Historians long have disagreed on this vital issue. Maureen Jung argues that mining corporations were a catalyst for the growth of subsidiary industries, but the corporations also tended to divert funds from more productive uses. St. Clair comes down squarely on the side of those who see the Gold Rush as a stimulus to California industrialization. He demonstrates that California manufacturing grew rapidly during the gold-rush years for several reasons: the great boom in population led to an increased demand for consumer goods; industries linked to mining expanded to provide needed products and services; and the infrastructure developed for the mineral extraction industry was eminently transferable to other sectors. A spirit of innovation and flexibility thus was generated in the Gold Rush that became the hallmark of California's entrepreneurial dynamism. "Perhaps the greatest legacy of the Gold Rush," St. Clair concludes, "was not its ability to attract gold miners, but its ability to attract entrepreneurs who seized the opportunities that gold offered."

Larry Schweikart and Lynne Pierson Doti discuss the role of banking in the gold-rush economy. After surveying the regional financial landscape prior to 1848, they affirm that the gold discovery changed fundamentally the way Californians did business. Developing in a region where "hard money" was in abundant supply and at a time when antibanking sentiment was virulent, financial institutions in the Golden State had serious obstacles to overcome. Schweikart and Pierson Doti reveal how those obstacles were surmounted and explain the ways the Gold Rush informed the early economic development of the state. "Banking and the financial sector," they argue, ". . . evolved in often distinctive ways because of the gold-rush economy.

Lawrence James Jelinek reaches a similar conclusion in his essay on ranching and farming during the Gold Rush. The old Mexican ranchos boomed temporarily following the gold discovery and then entered a period of steep decline. Open-range grazing gave way to breeding and fattening ranches, and land ownership became

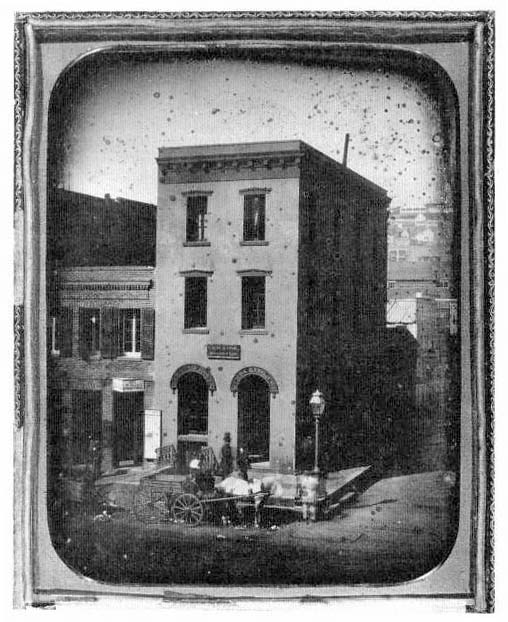

The banking house of James King of William, located on the corner of Montgomery and

Commercial streets in San Francisco, 1854. Founded by the Georgetown, D.C., native who

appended the "of William" to distinguish himself from others of that name, the bank was

one of the earliest established in California. Courtesy Wells Fargo Bank .

concentrated in the hands of a few highly successful agrarian entrepreneurs. Cultivation of crops, on the other hand, was brought to a "near standstill" in the early years of the Gold Rush, as people and capital moved into mining, but later boomed to meet the needs of a rapidly expanding population. Wheat farming on a massive scale led to the rise of an itinerant and multiethnic agricultural work force, what Carey McWilliams called California's "peculiar institution." Viticulture and the development of orchards followed the wheat boom as California agriculture became more diversified. State support for farming developed with the realization that gold alone "could not permanently underwrite a healthy economy."

The Gold Rush was also a time of far-reaching developments in transportation, as A. C. W. Bethel demonstrates in his catalog of California conveyances. Bethel surveys the various modes of transportation that brought the Argonauts to California, as well as the evolution of intrastate pack trains, freight wagons, riverboats, stagecoaches, and railroads. The rapid growth of the gold-rush population and its distribution throughout the state's interior stimulated the development of California transportation. Bethel's findings support the conclusion of David St. Clair that the mining of gold produced an infrastructure, including an array of transportation options, that facilitated growth in other economic sectors.

The final essay summarizes the overall economic significance of the Gold Rush. Gerald D. Nash ties together the observations of all the other essayists, concurring that "the Gold Rush helped to trigger momentous economic changes. In the language of economists, it served as a multiplier—an event that accelerated a chain of interrelated consequences, all of which accelerated economic growth." Nash briefly notes the dimensions of that growth in manufacturing and industry, banking and finance, agriculture and transportation. He also emphasizes the worldwide ramifications of the Gold Rush, tracing its impact on the peoples and economies of Latin America, Europe, the Pacific, and Asia. Nash's conclusion is far-sweeping: "In many ways, the California Gold Rush precipitated a veritable economic revolution in the state, the nation, and the world. Production of precious metals affected price levels, labor, wages, capital investment, the expansion of business, finance, agriculture, service industries, and transportation." Yet there was more. Nash also reminds us of the psychological and philosophical dimensions of the Gold Rush, for surely this epoch-making event "touched a deep-seated nerve in the human psyche." Forces were unleashed, for good or for ill, that would transform California forever into a Golden State.