Large-Scale Investment in California Winegrowing

Livermore was hardly alone in the combination of wealth and winemaking. While hundreds of farmers and small businessmen were planting vines and making wine in commercial quantities, there were at the same time a good many individuals and organizations of great wealth busied in the same work. They define the second pattern of the development of this generation in California. The vine has always been one of the ornaments of wealth and power. Greek and Roman aristocrats owned vineyards and competed with their wines as they might compete in racing fine horses or in collecting rare manuscripts. In the Middle Ages princes of the church as well as secular princes owned vineyards and patronized the arts of viticulture and enology. The same attraction operated in California. The early San Francisco banker William Ralston, who had a hand in California enterprises ranging from silk mills to mines, all financed by lavish and irregular loans from the Bank of California, was a major promoter of the Buena Vista Vinicultural Society, Haraszthy's ambitious organization in the 1860s. The collapse of the bold schemes of the Buena Vista Society and the bizarre death of Haraszthy were matched by Ralston's fall to ruin and his death in San Francisco Bay. As early as 1859 one of the state's first millionaires, the hard-drinking renegade Mormon Sam Brannan, sank a large part of his fortune in a property in the northern Napa Valley where, having named the place Calistoga, he set out to create both a health resort at the local hot springs (California plus Saratoga Springs yielded "Calistoga") and large-scale vineyards. He failed in the speculation, though the vine-growing part was successful enough. Brannan commissioned an agent to send thousands of cuttings of the best varieties to him from Europe, and in a couple of years had some 200 acres in vines. Brandy rather than wine seems to have been Brannan's main production for the market, and he was trying to get Ben Wilson of the Lake Vineyard to take over the Calistoga wine interest by 1863. [31] Though Brannan was the first Californian of great wealth to take up winegrowing, he did not take it very far.

The most ambitious and sustained application of California's early wealth to winegrowing came from Leland Stanford, one of the Big Four with Collis P. Huntington, Charles Crocker, and Mark Hopkins; wartime governor of California, U.S. senator, and founder of the university named for his son, Stanford was one of

the great powers in the state throughout the latter half of the nineteenth century. Stanford's interest in California wine went back at least as far as 1869, when he bought property at Warm Springs, along the southern shores of San Francisco Bay in Alameda County, from a Frenchman who had some seventy-five acres of grapes planted there. Stanford installed his brother Josiah on the property, and there the brothers began making wine in 1871. By 1876 production at Warm Springs Ranch was up to 50,000 gallons.[32]

In 1880 Stanford travelled with his family to France and there paid visits to some of the great chateaux of Bordeaux: Yquem, Lafite, and Larose among others. Whether this experience was the direct inspiration for what followed next is not known, but it seems likely, for on his return Stanford determined to become a great wine producer. The flourishing enterprise of L. J. Rose at Sunny Slope, with its big new winery, may also have stimulated Stanford's competitiveness. In 1881 Stanford began buying large quantities of land along the Sacramento River in Tehama and Butte counties, between Red Bluff and Chico, with the announced aim of growing wines there that would rival the best of France. The property was part of the old Lassen grant and already had a winegrowing history. Peter Lassen himself had planted Mission vines as early as 1846; in 1852 he had sold what remained of his grant to a German named Henry Gerke, who extended and improved the vineyards and successfully operated his winery through most of the next three decades.[33]

When Stanford took over, things changed dramatically: in one year a thousand acres of new plantings were added to Gerke's modest seventy-five; vast arrangements of dams, canals, and ditches for irrigating the ranch were constructed, fifty miles of ditch for the vineyards alone; a number of French winegrowers were brought over and housed in barracks on the ranch; a winery, storage cellar, brandy distillery, warehouses, and all other needful facilities were built, no expense spared. The new-fangled incandescent lights were installed in the fermenting house so that work could be carried on night and day during the critical time of the vintage. All the while Stanford continued to add to the acreage of his ranch, now called the Vina Ranch after the nearby town that Henry Gerke had laid out. Lassen's original grant from Mexican days extended over 22,000 acres, but Lassen had not been able to hold it long, and by the time Gerke appeared Lassen's ranch had dwindled to about 6,000 acres. Gerke, too, had sold off parts of the property, so that Stanford's first purchase was but a fragment of the original Mexican grant. Stanford simply kept on buying once he had started, however, and by 1885, when he appears to have thought that he had enough for his purposes, the Vina Ranch spread over 55,000 acres of foothill pasture and valley farmland—some 20,000 acres of the latter.[34]

The moral of this enterprise, larger and more costly than anything else ever ventured in California agriculture to this point, was not long in appearing: size anti wealth are not enough to make up for lack of experience. The circumstances were all wrong for what Stanford wanted to do, and though the Vina property was lovely to the eye and richly productive in all sorts of crops, it did not and never

91

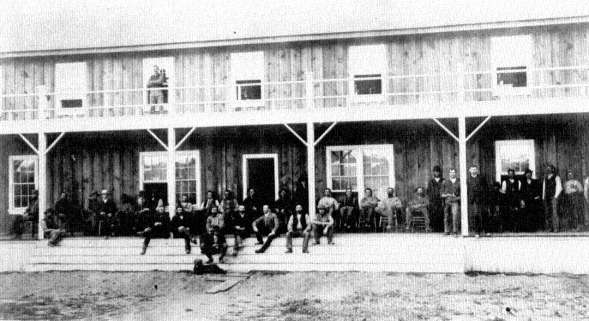

Workers at Leland Stanford's Vina Ranch on the verandah of their boarding house. There are thirty-seven

men and one dog in this picture, taken in 1888. and they were probably only a fraction of those employed

on the ranch and in the winery. The picture was taken by George C. Husmann, son of Professor George

Husmann. (Huntington Library)

could have made fine table wines. It was, in the first place, too hot in the summer for the grapes from which the noble wines come. The ranch lies in what is called, in the classification of California winegrowing lands, region five, the hottest of the five classifications, more like Algeria than Alameda. Its soil, too, was richer than that which good wine grapes need—they always prefer the poorer to the richer; and, finally, there was not enough experience yet in California with the bewilderingly wide range of Old World grape varieties and their possibilities. As has already been said, the matching of the right varieties with the right soil and climate is a work still going on and bound to continue for many years. It cannot be hurried, since not until the trial has been made can one know whether the right match has been found and one can hardly expect that what has required centuries in Europe will occur overnight here.

The force of these considerations was made clear within a year or two of the first vintage at Vina, which took place in 1887 with a harvest of several thousand tons (three earlier harvests had been sold to other winemakers). By this time there were 3,575 acres of vines planted, and a wine cellar with a capacity of two million gallons of storage had been built to receive the yield from this sea of vines. To supervise the work, Stanford had hired one of the master winemakers of the state,

Captain H. W. McIntyre, who had been winemaker to Gustave Niebaum at Inglenook in the Napa Valley and president of the state association of grape growers and winemakers.[35]

Evidently, all that could be done had been done, and yet the wine was a disappointment. No clear report about the character of the table wine produced is on record, but the circumstantial evidence is eloquent. The original selection of varieties, for one thing, was mistaken. Stanford planted Burger, Charbono, Malvoisie, and Zinfandel in his first expansion of the Vina vineyards; the cuttings, incidentally, came from the San Gabriel Valley vineyards of L. J. Rose, and this itself was a bad sign.[36] Burger wine was a Rose specialty, and he had particularly promoted it as greatly superior to the Mission. That was true, no doubt, but still faint praise. Burger, for white wine, does not make a distinguished table wine no matter where it is grown; the Malvoisie is an excellent source of sweet wines; only the Charbono and Zinfandel, red wine grapes, can be expected to yield good sound wines for the table, but that is when they are grown in the cooler hills and valleys of the state. Later, Stanford introduced a selection of other varieties, including the Riesling (though Gerke seems to have had this grape before Stanford's day), Cabernet Sauvignon, Malbec, Sauvignon Blanc, and Semillon.[37] But the lesser varieties continued to dominate, and in any case the finer varieties could never have produced wine comparable to what they yield in a suitable climate. As though to underline the uncertainties of Stanford's experiment, native American grapes were also included in the mix of varieties that were tried at various times: the Catawba, Herbemont, and Lenoir, varieties that have since entirely disappeared from California viticulture.

By 1890, only the fourth vintage at Vina, the entire huge production of 1,700,000 gallons of wine from 10,000 tons of grapes was distilled into brandy.[38] No more telling comment could be made on the collapse of Stanford's hope to rival the best that Bordeaux could produce. This is not to say that the vineyards and winery were a failure; only that the much-publicized aim of producing outstanding table wine was not met, and could not have been met. What could be done was to produce quite good sweet wines—baked sherry, angelica, port—and large quantities of brandy that acquired a high reputation. One experienced New York dealer of the time recalled Vina brandy as "more like cognac than anything made in this country," [39] and there are other testimonies more or less agreeing with this. The Vina angelica was judged the best of that sort exhibited at the great Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893. [40] But these compliments, and a scattering of others like them, are a sad anticlimax after the high and boastful intentions with which the Vina experiment started.

Stanford's winegrowing was not confined to Vina or to Warm Springs. He had grown grapes on his Palo Alto ranch in San Mateo County ever since he purchased it in 1876; in 1888 he built a winery there, perhaps in recognition of the fact that something better was needed than Vina was able to provide. Wine was produced and sold there under the Palo Alto label, on the Stanford campus, down to 1915,

but the scale of the enterprise was not comparable to that at Vina, and Stanford does not appear to have put a special effort into its success.[41]

For all the fact that it was widely and regularly written up in the California press, as a sort of standing feature subject, the Vina Ranch seems to have had curiously little impact on the life of the state. Its practices in grape growing and wine-making did not point the way to the future but gave only a sort of object lesson of what was to be avoided. The labor on the ranch was mostly provided by Chinese and Japanese workers, isolated from the general life around them.[42] And the production of the ranch was almost entirely sold to New York markets, so that a bottle of Vina brandy or of Vina wine was rarely seen by a California buyer.[43] The whole thing seemed to exist outside the view of the ordinary citizen of the state.

Stanford died in 1893. The Vina Ranch had already passed into the endowment of Stanford University, and once Stanford himself was no longer around to indulge his hobby interest in the property, his widow and the university trustees followed a very different style in its management. Captain McIntyre took his departure; Mrs. Stanford fired 150 employees and cut the salaries of everyone who remained. Vineyard acreage was reduced and land planted to other crops like alfalfa and wheat.[44] All the while, the university grew more and more embarrassed by its position as a major producer of wine and brandy in the face of growing prohibitionist disapproval of such an unholy connection between Demon Rum and godly education. Worst of all, David Starr Jordan, the university's first president, was a vocal prohibitionist himself. Stanford University's somewhat shamefaced part as proprietor of a great vineyard persisted, however, until 1915, when a final harvest of 6,000 tons from the vines of Vina was sold off to Lodi winemakers and the vines themselves uprooted. A few more years and the ranch itself had been dispersed by sale. After passing through different hands, the central part of the old ranch, including the vast cellar, with its two-foot-thick walls of brick, was sold to the Trappist monks in 1955; now they cultivate their gardens in silence there, at Our Lady of New Clairvaux.[45]

To judge from a number of the published accounts of Stanford's "failure" at Vina, their writers take a barely concealed satisfaction in the thought of a very rich man's inability to buy what he wanted. The Vina Ranch was in fact a double disappointment for Stanford, for he had meant it not only to produce fine wines but to be an inheritance for his beloved son, Leland, Jr., whose early death in 1884, at the very moment when the great vineyard plantings were going on at Vina, must have taken the heart out of the enterprise for the father.

But if the story invites some threadbare moralizing, it did not discourage other men of wealth from venturing on the chances of winemaking. Nothing so grandiose has since been attempted by an individual in California, but the record of late nineteenth-century winemaking in the state is studded with the names of the rich, the fashionable, and the powerful. Two of Stanford's fellow millionaires and fellow senators owned extensive vineyards and made wine: the Irishman James G. Fair—now remembered for his Fairmont Hotel in San Francisco—at his Fair

Ranch in Sonoma County, and George Hearst, father of William Randolph, at the Madrone Vineyard in Glen Ellen, Sonoma County.[46] In Napa, the Finnish sea captain Gustave Niebaum, made rich from the traffic in Arctic furs, bought the Watson vineyard, called Inglenook, near Rutherford, in 1879 and proceeded to make of it not merely a model winery but a successful model. Niebaum could afford to take his time, being a wealthy man, and wisely did so, with distinguished results. Not until after he had had a chance to study the subject in Europe did he make his decisions. He chose superior varieties, constructed a state-of-the-art winery, and put the work in the hands of experts. The results were excellent, and were quickly recognized as such.[47] In the Livermore Valley Julius Paul Smith, with a fortune derived from the California borax trade, made a speciality of fine winegrowing at his Olivina Vineyard; like Stanford, Smith had visited Europe to study its vineyards and wines; unlike Stanford, he chose a site that rewarded his expectations. Olivina Vineyard wines had a great success in New York, where Smith opened a large cellar.[48]

Smith had two prosperous neighbors who also took up winegrowing: at his estate of Ravenswood, south of Livermore, the San Francisco Democratic boss Christopher Buckley—the "Blind White Devil," as Kipling tells us he was called[49] —amused his intervals of rest from the implacable wars of city politics by making wine from his 100 acres of grapes.[50] At the Gallegos Winery, in nearby Irvington, Juan Gallegos, a wealthy coffee planter from Costa Rica, built a wine-growing enterprise on a large scale, and had the technical assistance of the distinguished Professor Eugene Hilgard of the university. The Gallegos vineyards, of 600 acres, incorporated the old vineyard of Mission San Jose from the days of the Franciscans. When the Gallegos Winery was destroyed by the great earthquake of 1906, it had become a million-gallon property.[51]

Far away in the south of the state, General George Stoneman, Civil War hero and governor of California, set out a large vineyard and built a winery in the early 1870s at his magnificent estate of Los Robles, near Pasadena (or the Indiana Colony, as it then was); another governor, John Downey, joined with the banker Isaias Hellman in developing their winemaking property in Cucamonga.[52] Downey, it will be remembered, was the governor who had appointed Haraszthy a state viticultural commissioner in 1861. Just south of Los Angeles, Remi Nadeau, once mayor of Los Angeles, developed a mammoth vineyard of over 2,000 acres beginning in the early 1880s; poor Nadeau committed suicide in 1887, and the vineyard property seems to have gone into residential subdivisions in the land boom that swept over southern California in that year. Not, however, before a winery, an "immense affair" according to contemporary description, was built to receive the expected flow of grapes from the Mission, Zinfandel, Trousseau, and Malvoisie vines on the property.[53] Nadeau's was not only the largest but the last moneyed plunge into winegrowing in Los Angeles County.

Winegrowing on a big scale was undertaken not only by wealthy individuals but by stock companies, after the earlier model of the Buena Vista Vinicultural So-

ciety. The most notable of such attempts in the eighties was that of the Natoma Vineyard, near Folsom in Sacramento County, the property of the Natoma Land and Water Company, itself one of the enterprises of Charles Webb Howard, one of California's baronial landowners. The company first experimented with different varieties, and then began planting vineyards on its land in 1883; by the end of the decade, it had 1,600 acres of wine grapes and had built a winery of 300,000 gallons' capacity. The operation was self-contained and tightly organized: a foreman's house and barns were provided for each 400 acres of vines, and at the winery itself, at the center of the property, there were houses for the superintendent, an accountant, and their families.[54] The expert George Husmann, writing in 1887, declared that the Natoma Vineyard was the most exciting development in California, "a most striking illustration of the rapid advance of the viticultural interests in the state,"[55] and an influence for the general improvement of the industry through its experiments with different varieties suited to California. The original mover and shaker of the project, Horatio Livermore, left in 1885, however, and his plans were not carried through as originally drawn up. The California wine trade had entered into its long depression, and by 1896 the company had leased its vineyards to other operators.[56]