One—

Patronage—and Women—in America's Musical Life:

An Overview of a Changing Scene

Ralph P. Locke and Cyrilla Barr

The Development of America's Musical Institutions

Music has always been a much-practiced, highly variegated activity in the United States. This musical diversity, and the contentious partisanship that has marked certain branches of it (such as the recurrent tension between supporters of "classical" and "popular" music), reflect various more fundamental diversities and tensions within American life, involving such factors as race, ethnicity, social class, geography, and means of livelihood (e.g., agricultural communities vs. cities).

Long before the arrival of settlers from across the sea, Native Americans had developed rich and varied traditions of ritual dance and song; European colonists and enslaved Africans carried with them from across the sea the musical dialects of their various places of origin and the desire to continue making music in ways (and on instruments) familiar and meaningful to them. These various musical traditions—Native American, European, African, and others not yet mentioned—then blended here into new hybrid languages and genres, but the extent and proportions of the blending varied a great deal. The musical melting pot particularly welcomed certain stylistic elements from one or another of these repertoires or musical traditions: for example, the hierarchically structured harmonic vocabulary of European art and dance music combined in diverse ways with certain improvisatory rhythmic practices from African traditions, especially various kinds of syncopation. Other repertoires and traditions, notably the various Native American musics, tended to have much less impact on the country's emerging musical styles and genres. (Scholars cite various inhibiting factors, technical as well as cultural.)[1] This selective process of interethnic musical contact was particularly fruitful in what H. Wiley Hitchcock calls America's "vernacular" genres, such as the African-American spiritual (leading to today's gospel music), the minstrel show and musical comedy, ragtime, jazz, and, more recently, salsa and other styles featuring prominent Caribbean (African-Hispanic) elements.[2]

Parallel with the broad stream of "vernacular" music making (which of course also includes more strictly European-derived genres such as Anglo-American ballads and Country-Western music) flows what Hitchcock calls the "cultivated" stream, which concerns us in this book. In the mid nineteenth century this consisted of an entirely European-based yet cosmopolitan set of practices, preferences, and repertoires, including a more or less canonical yet eclectic corpus of sacred and secular works—for example, Handel's Messiah , Donizetti's Lucia di Lammermoor , and piano pieces by Stephen Heller, a Hungarian Jew who had, like the Polish Chopin, made Paris his home and successful base of operations. These diverse works were transplanted more or less intact to the New World, and to them were added, increasingly with the passing decades, American works written firmly in this European tradition (e.g., church hymns of Lowell Mason, the Italian-language opera Leonora by William Henry Fry, and piano music of William Mason and the German émigré Charles Grobe).

Certain strands of "cultivated" music making remained stylistically "frozen" for decades after first arriving on these shores: the German-speaking Moravian settlers of Pennsylvania and North Carolina, for example, for decades performed a relatively stable repertoire of string trios, choral motets, and the like, in a style close to that of Franz Joseph Haydn, and occasionally added to it new pieces written in a closely similar style. Such unaltered continuity, though, was the exception to the rule. For the most part, the repertoire of "cultivated" music in America changed a good deal over the course of the nineteenth century, thanks not only to local influences but also to America's continuing contact with the Old World. The latest pieces were shipped over, hot off the press, along with Irish linens, Scotch whiskey, French perfumes, and the latest installments of Dickens's novels.

By around 1870, many of the best young American musicians were going to Europe to study with the pianists Franz Liszt and Theodor Leschetizky, the violinist Martin Marsick, the singer Mathilde Marchesi, and other famed teachers in Paris, Vienna, and elsewhere, then returning to America to perform the pieces they had heard and learned—for example, Liszt's Hungarian Rhapsodies and the Parisian operas of the German-born but Italian-trained Giacomo Meyerbeer—and, in many cases, to compose in up-to-date style and to teach.[3] As early as the 1820s, significant numbers of well-known opera stars and virtuoso instrumentalists, eventually including the Swedish soprano Jenny Lind and the Norwegian violinist Ole Bull, came from Europe on concert tours. Some stayed for years or even settled here permanently.[4] Also, many of the larger cities, especially on the eastern seaboard, enjoyed performances by traveling opera companies such as the one led by the tenor Manuel García (father of the great singers Maria Malibran and Pauline Viardot), since at that point few cities had their own self-supporting resident troupes. New Orleans was the earliest exception and, "for much of the century," one scholar plausibly concludes, enjoyed "the best opera to be heard in America"—sung mainly in French, of course.[5]

"Cultivated" music, it should be stressed, extended its domain far beyond the

A few paragraphs from this chapter appeared, in somewhat different form, in Ralph P. Locke's overview article, "Paradoxes of the Woman Music Patron in America," Musical Quarterly 78 (1994): 798–825. In addition to the people thanked in the Acknowledgments, Laurence Libin (Metropolitan Museum of Art) gave good advice and encouragement.

concert hall and opera house. For one thing, there were few such halls until late in the nineteenth century, and even professional concerts tended to be presented in a wide range of venues: theaters, Masonic halls, parks and pleasure gardens, train stations. But formal (and informal) concerts were but one of many outlets for the love of "cultivated" music in late-eighteenth- and nineteenth-century America. Throughout the land, music of what we might call the "light classical" variety was a prime form of leisure-time activity and social entertainment. Dancing, for example, was accompanied by a few string and wind players, or maybe just a single violinist. (Dancing masters in America, as in Europe, played a special "kit" fiddle small enough to slip into the coat pocket.) Children of the middle and upper classes were early trained to play instruments—for girls, these were most often guitar, harp, harpsichord, or piano—or to sing, delighting family and friends with keyboard pieces such as Frantisek[*] Koczwara's[*] internationally beloved The Battle of Prague (first published in Dublin around 1788) or tuneful vocal excerpts from European operas.[6] (Among the best loved, in the 1860s and 1870s, were Giuseppe Verdi's Il trovatore , Sir Michael Balfe's The Bohemian Girl , and Charles Gounod's Faust .)[7]

Hard as it may be to believe today, amateur music making in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, indeed even in the first half of the twentieth, did not cease when a child finished his or her teenage years. Adults regularly gathered to play chamber music and sing together; Thomas Jefferson, an avid violinist, made frequent use of his large collection of the latest imported trios and such, and many people knew the singing voices of their parents, siblings, or spouses well, having sung hymns, Stephen Foster songs, or operatic excerpts together at the parlor piano. Choral groups thrived in the churches, and by 1800 also in other meeting halls, sometimes handily mastering the hymns and secular partsongs of home-grown composers such as William Billings, and sometimes working their way in determined fashion through the demanding but rewarding oratorios of Handel, Haydn, and other European masters. Bands and small orchestras, too, sprang up everywhere, playing opera overtures, movements of symphonies, song arrangements, marches, waltzes—almost anything that had a pleasant tune and enough regularity of beat and phrase to set toes happily tapping.

All of this—from quadrilles for dancing, to choruses and bands—provided the fertile soil from which many of the musical institutions of America that support and promote "serious" or "classical" music sprang. (Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge's attachment to music, for example, was surely rooted in the family musicales of her youth, described lovingly in her mother's little booklet, Pleasant Memories of My Life .)[8] The development was long and troubled, and, in the nation's early decades, little patronage was in place to help it along, whether from institutions or individuals of wealth. As Richard Crawford points out:

[Whereas Europe has had a centuries-long tradition of church, court, and state patronage of] music of the highest quality[,] . . . in America neither a national church,

nor an aristocratic court existed, and the state's need has been limited to simple music for utilitarian functions [e.g., military bands]. . . . Foremost of the shapers [of America's musical life] have been the musicians themselves, who have worked as individuals in a commercial environment seeking to satisfy the needs of various social groups—for artistic expression, worship, instruction, entertainment, or participatory recreation.[9]

Private citizens took lessons from music masters and even hired professionals to play chamber music with them or to perform for their guests. One such melomane, Elizabeth Ridgely, possessed a musical library in the 1820s that testifies to her openness (and that of her French-born teacher) to a wide range of current European music and suggests that a substantial amount of amateur and professional music making went on at the Ridgelys' manor house (Hampton, Maryland).[10]

But the first real "wave" of patronage as it is currently understood seems to come in the 1830s. It was then that Lowell Mason and Boston's Handel and Haydn Society began carrying out energetic organizational and promotional labors on behalf of music in the schools, churches, and concert halls.[11] Far less well known are the efforts, around the same time, of various groups of parishioners—especially women—to raise money to buy organs for their churches (see Vignette A). From then onward into the late twentieth century, patrons increasingly vied with the musicians themselves in their dedication to and active organizational work for the benefit of art music in America.

The crucial, formative moment of music patronage in America, and of "classical music" generally, occurs in the decades just before and after 1900. During those years many of the institutions and practices that have remained characteristic of American musical life ever since were established and put on a firm financial and organizational basis. These institutions and practices include the symphony orchestra, with its season-ticket holders in sober or sometimes even formal attire (and its small-town equivalent: the half-amateur, half-professional community orchestra, often playing in a school or college auditorium, church, or town hall);[12] the opera house with its decor in red plush and brass and its international casts, often singing in a foreign language; the conservatory and music school, earnestly filling the growing demand for trombonists, for coloratura sopranos, even for composers pondering, in newspapers and magazines, such questions as "Should we be writing symphonies in a distinctively American style?"; publishing houses churning out songs and piano pieces in sheet-music format for the amateur to perform at home or in small assembly; the newspaper column boosting or blasting the visiting artist or the local luminary; secondary-school bands and choruses, teacher-training programs for those who would lead them, and of course the private vocal or instrumental studio; instrument factories and dealers to provide homes and schools with cheap but solid flutes and pianos (as well as elaborate, decorated art-case grand pianos for the White House and for mansions ranging from that of the Dohenys in Southern California to the homes of the Marquands and the Vanderbilts in Manhattan); elementary courses in music appreciation,

whether for grade-schoolers, college students, or concertgoing adults; and graduate programs and tenured university chairs in music and its scholarly study. (From this long list of activities in music, a few have long been particularly identified with women: public school teaching, choral conducting—but not orchestral or band, except with all-female ensembles—and of course performance and studio teaching in voice, piano, and harp. Later in this chapter, we shall return to the question of women's expanding place in American musical life.)

Everything mentioned in the previous paragraph existed only in embryonic form, if at all, in the mid nineteenth century; nearly all of it had taken recognizable shape—and much of it was fully developed and flourishing—by the 1920s.[13] As one very concrete example, in 1870 the music holdings of the Library of Congress comprised an oddly assorted five hundred items; by 1917 the Library could boast a well-organized Music Division, its near-million items carefully selected and overseen by Oscar Sonneck, a world-class musicologist.[14] The sudden growth in America's musical life over but a few decades echoed developments taking place in the visual arts—for example, museums—and indeed other sectors of American life entirely, such as hospitals and public schools. The American university, the historian Robert A. McGaughey notes, hardly existed in 1870, but by around 1914, it "had acquired a form little changed since."[15] Furthermore, many of these other "sectors" have their own important musical aspect: it was during the decades just before and after the turn of the century that, consonant with the ideals of the Progressive movement, choral singing and music appreciation courses began finding their way into the public school and into that parallel institution for immigrants, the settlement house.[16]

Of course, the more things stay the same, the more they change. Musical life has been greatly altered since the 1920s by shifts in American demographic patterns (the shift of money and power from our urban centers to the suburbs or indeed to other geographic areas entirely, such as, recently, the Sunbelt) and by cultural values that increasingly emphasize instant gratification as a goal, to be attained through the purchase of commercial goods.[17] More particularly, the rise of technology in the service of the consumption principle just mentioned has resulted in a shift away from "live" and participatory music making and toward listening to recordings; this process, set in motion by the arrival of the home phonograph around 1890 and the home radio around 1925, intensified with the ever-increasing fidelity of sound reproduction and the proliferation, since around 1970, of tape cassette players—especially as portables (ranging from "boomboxes" and pocket-size machines with headsets to sound systems in automobiles). Opera, in particular, has gained a major and often sophisticated "second" audience in the past ten years; thanks to electronic video (whether in the movie theater or on television, videotape, or video disc), opera lovers, even in isolated locations, can "attend" performances of once little-known operas such as Verdi's Stiffelio , experience the dark power of Wagner's Ring cycle or Britten's Peter Grimes , and be devastated by the artistry of Teresa Stratas, Julia Migenes, or—in a gripping black-and-white video of Tosca , act 2—Maria Callas. (For further discussion of the opportunities

and challenges presented by electronic technology, see Chapter 10.) But "canned" music, even at its best, cannot replicate the experience of being part of a performance's "first" audience, that is, of hearing music in person, in a good hall, amidst a mutually inciting throng of several hundred or several thousand attentive listeners; and, for better or worse, America's system for delivering live performances of Western art music to the public (or for the public to make such music itself) remains, in its broad features, the one put in place around 1900.

The growth and systematization—the "modernization," in the sociologist's term—of America's musical life around 1900 resulted in large part from the nation's immense industrial and economic expansion at the time, as the growing middle and upper classes, and even certain sectors of the working masses, increasingly found themselves with surplus cash and the leisure time in which to spend it: on modestly fashionable clothing, on books and magazines filled with enticing ads for consumer products, and, not least, on outings to amusement parks, theaters, and concert halls.[18] Hilda Satt, a young immigrant woman at Jane Addams's Hull House in Chicago, no doubt spoke for throngs of working people when she later recalled as among her chiefest pleasures attending performances of opera and musical comedy; works such as The Merry Widow "were a good tonic after a day of hard work," and she considered herself privileged to have seen and heard such gifted operatic interpreters as Enrico Caruso and Jean de Reszke, Marcella Sembrich and Emma Calvé, and "the great Chaliapin."[19]

Some of the musical institutions mentioned earlier—publishing, journalism, the instrument trade—sprang up more or less spontaneously, in response to the pressures of the marketplace. But Beethoven symphonies and Wagner operas require long, costly rehearsals involving fifty or even a hundred highly trained, specialized performers. (Legendary Tristans, such as Jean de Reszke, do not come cheap.) The laws of supply and demand simply could not produce affordable, accessible, yet still worthy performances of such works, any more than it could produce universities or hospitals. Federal and local governments have throughout most of the twentieth century provided cultural and charitable organizations with certain financial protections through income-tax deductions and local property-tax exemptions, but direct, European-style government aid would have been needed as well in order to fill the gap. Despite the early efforts of Jeannette Thurber and others to change federal policy, direct aid was not a politically acceptable option until the creation of the—relatively modest, by European standards—National Endowment for the Arts under the Johnson administration in 1965. One 1930s precedent for the NEA, though, should be mentioned. The New Deal's program in the arts (e.g., the Federal Theater Project) was intensely controversial and, in the end, more a stopgap measure than a permanent governmental fixture. Memory of it fades with the passing years: its "Dime Concerts" in athletic stadiums, its hundreds of music-teaching centers across the country, and its creation—in 1936, in New York City—of the nation's first public high school for music and art.[20] Still, it may serve to remind us that, if Americans want it

enough, we can do things at the governmental level to increase democratic access to music.

Patronage:

Individuals and Foundations

Since the marketplace did not support orchestras, opera houses, and professional (or even preparatory-level) music schools, and since government money was rarely forthcoming, the gap was filled, as it was in other areas such as social work, by patronage—taking the word to include also volunteer organizational work (unpaid labor).[21] Patronage could and often did involve networks of small patrons: an orchestra's subscribers often made individual modest financial and in-kind contributions beyond the price of their season tickets (see Chapter 2).

But the lion's share of patronage funds, especially in the decades around 1900, came directly from a small number of wealthy individuals and, to some extent, from the cultural "foundations" established by such individuals or their families. The great fortunes that piled up in the late nineteenth century were the direct result of industrial growth in an era of laissez-faire capitalism. Until the passage of the Sherman Antitrust Act in 1890, corporations, by virtue of their charters, were free to conduct business more or less as they liked, free of governmental regulation. As a result, the financial holdings of the Vanderbilt family, for example, reportedly exceeded those of all but a handful of the most developed nations of the world.[22]

Profits from industrial and other investments were so high that a family's income often far exceeded expenses, even after deducting for club memberships, yachts, town houses, country estates, world cruises, winters in sunnier climes, salaries for household staff, and bills for schooling, clothing, and medical care. How to dispense the excess—or, in the language of the time, how wealth was "stewarded"—depended greatly upon the individual's whims and interests. For many, this meant beginning to deal with the socioeconomic disasters created in part by the capitalist system that had made their own families so comfortable. (In this project they were encouraged by the important "social gospel" movement within the country's Protestant churches.)[23] For others, it meant building the American university, a development that, as Robert A. McGaughey notes, helped provide men of privileged class—including certain sons of the very men who had made the fortunes—with a way to make "respectable livings other than in the church or business."[24]

Fortunately for music lovers, the industrialists and their immediate families often gave a high priority to music, higher indeed than we today might think likely (given the stereotype of the inartistic business mind). This is strikingly illustrated in Andrew Carnegie's ranking of the projects that he deemed most worthy of philanthropic aid, wherein music—under the heading "suitable concert halls"—came in fifth, after public parks and before public baths.[25] He also put theory into practice, as music lovers in New York City and Pittsburgh have daily reason to recall.

Foundations were the other major beneficiary in a rich man's or, less often, woman's will, and were usually administered by a council of his or her surviving

friends and associates, lawyers and bankers, and some family members. There was as yet no "science of giving," and although some notable examples of foundations, such as the Peabody Foundation (1867), may be found in the late nineteenth century, few survived more than a few decades. Only in the twentieth century did foundations (e.g., Ford, Rockefeller, Guggenheim) become a major force in the cultural arena, strengthened by the creation of income tax, inheritance tax, and tax-exempt status.[26] Even so, music was slow to benefit.

In the early 1930s, the directors of the Carnegie Corporation financed a study to answer the questions "What aspects of music in America today seem the most important?" and "How can music best be furthered?" The findings were disseminated in Eric Clarke's Music in Everyday Life and Randall Thompson's study of music in the curricula of thirty liberal arts colleges in the United States.[27] While efforts such as these exerted a valuable influence upon corporate giving, the causes needing support grew apace. Philanthropy was beginning to develop as a fine art, shaped largely by corporate bodies whose chief executives were men.

The "Domestic Sphere"?

Women and Music in Home and Club

Parallel to this more or less official, highly institutionalized story runs the more fragmented story of the other half (at least) of America's music lovers, the women, whose patronage and volunteer work is explored in this volume. By the last decades of the nineteenth century, a significant number of them did have substantial money of their own (largely inherited), and in many cases, depending on the laws prevailing at the time in a given state, were free to spend it as they saw fit.[28] In addition, many women influenced the way their husbands' money was disbursed, at least in matters over which they were considered to hold some authority, such as education and, precisely, the cultivation of the arts. The musical initiatives of such women as Isabella Stewart Gardner, Bertha Honoré Palmer (of Chicago), and Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney owed much to the wealth and position of their husbands or fathers. Yet, whatever the sources of their money, these women often exhibited entrepreneurial savvy in its distribution and were in many cases guided by relatively democratic and (by standards of the day) well-informed views on social and cultural policy.[29]

Moreover, these patrons of music, like women who supported the visual arts, theater, and dance, carried out their work in venues that were more publicly visible than the institutions of social welfare devoted to the care of the sick and poor, aged and young, that had been the primary out-of-home arena for female reformers in the early and mid nineteenth century. In this way, they may have helped to prepare public acceptance of working women taking positions of authority for pay. And certainly they stand as major early examples of women who, freer of certain social limitations than most other women of their place and time, freer to act and to influence, could devote their energy and imagination to, in Mary Catherine Bateson's phrase, "composing a life" of varied and gratifying texture, not just

taking from the larger world but also interacting with it, indeed acting upon it in productive ways.[30]

Money, we said earlier, is only one way of contributing to a cause. Many women less affluent than a Mrs. Potter Palmer (but still "comfortable") assisted the growth of musical institutions primarily through volunteer work, including the raising of funds from others. These women most often remain nameless in the chronicles of the major symphony orchestras, festivals, and educational institutions that still bear the imprint of their devotion and generosity. Such "grassroots" work, in music or other areas, is therefore more difficult to chronicle but is nonetheless of crucial significance. Kathleen D. McCarthy has shown that women who had established a visual-arts organization were often expected, at the point where it had gathered a significant endowment or collection, to hand over control to a board of male managers, although the women may have remained active in various ways.[31] Similar phenomena occurred in the musical arena, as Linda Whitesitt notes in Chapter 2 below, reminding us of the ever-present tension between possibilities and limits for women in public life. Still, the musical clubwomen and volunteers, perhaps even more than the wealthy patronesses discussed in the previous paragraph, helped in their way to render "obsolete the notion that 'women's place is in the home,' and thereby made a significant contribution to women's struggle for autonomy."[32]

We should resist, though, the temptation to treat these various types of women patrons simply as rediscovered heroines.[33] Scholars in recent years have struggled to find adequate ways of describing the complexities and contradictions of the life of a woman of leisure or at least modest comfort in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. On the one hand, women at all social levels were limited to varying extents (less so in the case of poor and working women) by the ideology of the "female sphere," with its emphasis on "piety, purity, and submissiveness" in the service of "domesticity, nurture, and education."[34] On the other hand, women often developed their own strategies of resistance to such limitations, creating a rich web of emotional ties to relatives and to women friends that amounted at times, as Carroll Smith-Rosenberg and others have argued, to a distinctive "women's culture," full of mutual assistance and support. In comparison, the lives of middle- and upper-class men—often spent almost entirely in the "male sphere"—may appear to some of us today emotionally cramped and deprived.[35]

The tendency, among certain women's historians, to emphasize the positive, creative, interactive aspects of women's lives (and to doubt whether men's lives were quite as rewarding as sometimes advertised) might be accused of disguising or denying the existence of male privilege and female subordination. One needs always to keep in mind that men's constricted choices, unlike women's, helped prepare them for successful careers and for dominant, sometimes tyrannical control over the family's property, finances, and major life decisions (such as a child's choice of spouse); bourgeois men were indeed limited yet, as Marilyn Frye puts it, not oppressed.[36] But perhaps the renewed interest in the workings of the women's realm can be more fairly described, not as ignoring the dissymmetry of power, but

as taking it as given in a particular historical situation, the aim being, not to endorse or reinscribe the patriarchal system, but rather to explore the often meaningful lives that women made for themselves and their children within it and sometimes despite it.

Rigid gender differentiation was, one should stress, urged upon daughters at least as much by their mothers as by their fathers. Indeed, central to family relations in the nineteenth century was what might be described as a female "apprenticeship system," through which, as Carroll Smith-Rosenberg puts it, "older women carefully trained daughters in the arts of housewifery and mother-hood."[37] These arts receive less respect today than they once used to, given the increasing tendency among women to flee and sometimes to denigrate the lives of service that their mothers and grandmothers lived, and to model their own lives according to definitions of success and identity that are traditionally male (more or less equivalent to what Adam Smith described as "economic man," earning his own living and acquiring goods and services in the commercial marketplace). Today, women and men alike are faced with the challenge of balancing these competing ideals of economic interdependence and independence, resisting or accepting (colluding in?) "our society's widespread devaluation of care," as the "transformative feminist" Suzanne Gordon puts it.[38] As for earlier days, we should remember that many of the "arts" most despised today—housework, food preparation, sewing and darning, various physical aspects of child-care—required more skill, time, and physical exertion than they do today, yet were either essential to family health or helped limit expenses and thus formed in a sense a second income. And, at least in certain families, exercising these accomplishments and managerial skills graced the women who knew them with dignity and authority.

The tension between negative and positive readings of women's lives is thus not so much a matter of disagreement among scholars as a reflection of the tensions within those lives. And so there remains a certain peril for anyone who would attempt to comprehend just how women of an earlier era perceived themselves, their mission, and the relationship between that mission and other aspects of their lives. In some cases described in subsequent chapters of this book, the tugs and pulls are apparent: ambition for a career and for a sense of public validation is viewed as being incompatible with devotion to husband and children, and both of these may be hard to reconcile with societal expectations of other sorts. Seen in this context, a woman's activist work in the arts, especially when undertaken as part of a cooperative venture with other women, comes to seem a brilliantly functional solution to the contradictions of the life of the middle- and upper-class "lady": it reasserts her bond to others of her family and class and, simultaneously, enables her to "connect purposefully" to the larger community (the phrase comes from Nancy Cott's discussion of women's organized church groups),[39] all without threatening her husband's prerogatives as breadwinner in what one (male) observer at the time sensitively qualified as "the field of immediately productive work"

(our emphasis) and as player—if the husband were so inclined—in the arena of governmental politics.[40]

How clubs, and especially music clubs, helped connect women to other women outside their homes and to the larger world will become immediately apparent in Chapter 2.[41] For the moment, we can glimpse some of the feelings that such clubs tapped, including a sober desire for self-improvement and a generous willingness to share one's own privileges, by taking a brief look at the Friday Club of Chicago, founded in 1887, three years before the General Federation of Women's Clubs. Ellen Martin Henrotin, one of the group's prime movers, addressed the first gathering of these Chicago ladies in terms that left no doubt as to the implications of the club movement for the members themselves:

For years most of you have been hard at work at your studies. You have doubtlessly many original thoughts and theories which you will be glad to impart to others and also many of you have enjoyed educational advantages peculiarly your own, which you can thus share with others. If you never discuss literature and art, and if you allow society [i.e., empty socializing] to engross all your time and attention, you will even lose your love for serious things, and what can be more valuable to you as life goes on . . . ? The formation of such a club as this should be a very serious matter, for the mere fact of being a member of it may influence the term of your whole life.[42]

The Friday Club may have been making a bold statement in even designating itself as a "club." The word was more commonly associated with men's groups, which is likely why the (admittedly rather more "stuffy") Fortnightly of Chicago, founded fourteen years earlier, chose to eschew it in its title. That the ladies of the Friday Club enthusiastically supported issues that reflect a turning of attention toward the needs and aspirations of women is shown by papers read at meetings, such as "Women in Municipal Government" and "Modern Women in Recent Literature."[43] The group also maintained an active, indeed activist, music and art department: during the Depression, the club purchased and distributed season tickets to the Chicago Symphony, thus in a single stroke assisting the orchestra, its players (some of whom might otherwise have had to bear pay cuts or be laid off), and music lovers who in chilly economic times could not afford the privilege of attending.

The Rise of the Woman Musician

In this book we emphasize the contributions of wealthy women (frequently the daughters or wives of professional men or industrialists) and of women of lesser means who supported musical life equally—although in a different manner—but still also from the sidelines. This should not, however, lead us entirely to neglect the role of women performers and composers as activists in the cause of music and, by their very public presence, in the cause of women.[44]

The large lines of the story of the American woman musician can be told in

terms of what Linda K. Kerber calls "a Whiggish progressivism." Just as historians have tended to see the central theme of American women's political lives as "an inexorable march toward the suffrage,"[45] so the following account is based on the somewhat simplistic, yet not entirely misleading, view of the musical women of America as striking blow after blow for the right to make music under the same conditions as men.[46]

During the colonial period and continuing through much of the nineteenth century, American women were not permitted to make music seriously, professionally, publicly—as opposed to recreationally or consolingly in home or church. Furthermore, they were discouraged from even learning most kinds of instruments: loud, low, or bulky ones (trombone, tuba, cello, double bass), ones whose playing required unladylike facial contortions (oboe), and so on.[47] As mentioned earlier, this basically left piano and voice (and a few instruments of more limited repertoire, such as harp and guitar) as the primary options available to a young woman. Not by chance, these instruments were perfect for domestic performance: the harp and guitar were soft-toned and unclangorous, and the harp and especially the piano were archetypally nonportable, "indoor" vehicles and thus well-suited to women's home-centered lives. (The same can be said of the chamber organ, used in many homes to assist family hymn singing.) As for the voice, it required no training whatever, at least not for singing hymn tunes and simple ballads. Singing also had the advantage of involving words. The amateur female singer could proclaim her religious devotion through music, lead her children in song, or—especially if she had had a few lessons—repeat (and repeat), in the privacy of the home, the rejoicing or lamenting aria of some operatic heroine, excerpted from an opera that she had read about in a novel or a journalist's essay or had once, safely escorted, been privileged to see on stage. The few women who performed music professionally in these early years were mostly singers of opera and oratorio and, as Adrienne Fried Block has observed, often came from "a musical or theatrical family."[48]

In the second half of the nineteenth century, matters changed a great deal. Music and music teaching (the joint category used for many decades by the U.S. census) formed a rapidly expanding job sector; by 1900, Judith Tick notes, it numbered "8% of all professional workers" in the country. Women were a big part of this increase: between 1870 and 1910, the number of women holding jobs (including part-time work) in some aspect of music "increased eightfold, and the proportion of women in music rose from 36% to 60%, the highest it was ever to reach before 1970."[49] The proportion dropped after 1910 as the field expanded, became professionalized and better-paying, and began attracting larger numbers of men—a familiar pattern in women's history. (To be accurate, the raw numbers of female musicians and music teachers did increase throughout the first half of the twentieth century—but not as rapidly as before 1910, nor as rapidly as the numbers of males now entering the profession.)[50]

In the final decades of the nineteenth century, "a few American-born women emerged as professional performers and composers of vernacular and parlor

music and later of art music."[51] By century's end, women soloists—singers, violinists, pianists—were taking up performing careers that involved heavy concert tours. The circuit in those days extended far beyond the few (mostly East Coast) metropolises that had some sort of established symphony orchestra or opera troupe. As Oscar G. Sonneck remarked in 1916, "many western cities, barely out of the backwoods stage of civilization, . . . [are] pushing forward musically with such rapidity and energy that they have already changed the ways of musical America in a few years."[52] Such advances resulted in large part from the willingness of musicians and ensembles—the Theodore Thomas Orchestra, the Mendelssohn Club, and the Germania Society, but also such remarkable female performers as the violinists Camilla Urso and Maud Powell and the masterful pianist Fanny Bloomfield-Zeisler—to brave the inconvenience and hardships of touring the hinterlands.

Wherever they performed, women faced an additional hurdle: the prejudice against women professionals. Even the most distinguished fingerwork, the most searching interpretations, could not lay to rest the damning judgment "Plays well for a woman." The one early exception was opera, which could not do without women; nineteenth-century American society idolized the female star—while considering her, like actresses and women dancers, socially suspect—and paid her more than equivalent male singers. Some singers were multi-talented and in a later generation might instead have flourished as pianists, composers, or conductors (e.g., in Europe, Pauline Viardot and Marcella Sembrich).

The prejudices against women musicians in Western art music knew no borders. Saint-Saëns, for example, complained of the composer Augusta Holmès: "Women are curious when they seriously concern themselves with art. They seem desirous first of all to make one forget they are women, and to show an overflowing virility, without dreaming that it is precisely this preoccupation which betrays the woman."[53] Many an American critic, too, searched for such signs of ladies protesting too much.[54]

Despite prejudice and discouragement, American women in the early decades of the twentieth century did, increasingly, compose, give recitals (although, Olga Samaroff complained, for lower pay than men), and sing in public (even after marriage). They formed chamber groups, notably the Eichberg Ladies String Quartette and the Olive Mead Quartet, and larger ensembles such as the oddly titled Vienna Damen Orchester and the Boston Fadette Lady Orchestra (named for the heroine of George Sand's novella La Petite Fadette [1848]). By the 1920s and 1930s, when the ranks of the major orchestras in this country were still restricted to men, women founded full symphony orchestras of their own—playing all those long-forbidden loud and awkward and temptingly portable instruments—and also began an active epistolary campaign to break down the barriers restricting them from positions in the country's mainstream ensembles.[55] Maud Powell put the issue plainly:

Of course women should play in symphony and other orchestras, if they want the work. Wanting the work implies measuring up to the standards of musical and technical efficiency, with strength to endure well, hours of rehearsing and often the strain of travel, broken habits and poor food. Many women are amply fitted for work; such women should be employed on an equal footing with men. I fail to see that any argument to the contrary is valid. But if they accept the work they should be prepared to expect no privileges because of their sex. They must dress quietly and as fine American women they must uphold high standards of conduct.[56]

As for composers, they, by the nature of things, depended on the support of conductors. Mabel Daniels once confided to Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge that "when a woman undertakes to write seriously for orchestra she is looked at rather askance by conductors. . . . I'm just starting to launch a piece for full orchestra and the final question I was asked was 'Do you do your own orchestration?' which makes me furious."[57] When the British composer Ethel Smyth wrote to tell Coolidge that Oxford was finally making her a doctor of music, she added, "but except for Sir Henry Wood none of our conductors take my work to America—nor will they 'til the grave has done away with the petticoat element."[58] The situation was doubly prejudicial in the case of a talented woman performer or composer who also happened to be wealthy. Of the composer-pianist Mary Howe, the conductor William Strick-land remarked that "both her position and her sex militated against her: The former marked her as a 'dilettante,' and the latter prevented her from being taken seriously."[59] A number of the women patrons discussed in the present book, had they been born several generations later or been born into less wealthy families, would have made their marks, and their own livings, in some aspect of the professional music world. As it was, they made no livings from their music (most of them), but still, through patronage and activism, they made marks of a different kind.

Toward a Typology of Music Patronage

Women's organizational activities in music in the United States, as is becoming clear, are too extensive and varied to be easily encapsulated in simple generalizations,[60] much less in jokes and stereotypes.[61] Taken together with certain other recent scholarly work on specific patrons (e.g., by Catherine Parsons Smith) and set in the context of more general work on women's organizational activities in America (e.g., by Anne Firor Scott and Karen J. Blair), the studies in this book help reveal that women's patronage of music has comprised many widely differing activities, each of them distinctive in its internal dynamics and the interpretive issues it raises. These various activities can be helpfully examined by using categories proposed by Kathleen D. McCarthy for patrons of the visual arts. These three categories are analogous in many ways to the two rather simple ones that we employed in our Introduction ("individuals" vs. "groups"), but they make a further division, within the "groups" category, between "separatists" (by which McCarthy means

groups composed—programmatically and ideologically—of women, such as most art clubs and pottery guilds) and "assimilationists" (in this category she includes women who served on museum boards with men and who, too often, found themselves marginalized in various ways by male board members or by—again, male—museum officials). As for women who worked alone, McCarthy terms them not "individuals" but "individualists," thereby stressing that these (mostly very wealthy) women carried out their patronage work independently, each according to her own lights and often in areas of art that were neglected by the traditional museums (one example being Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, the moving force behind both the Museum of Modern Art and the important museum of American folk art in Williamsburg, Virginia, that bears her name).[62]

Of McCarthy's three categories, it is this last that makes the cleanest fit when transferred to music patronage. We tend to have particularly rich documentation of the activities of "individualist" women patrons in music, but, predictably enough, the abundance of data only reveals how diverse and often headstrong they were—hence hard to generalize about. One perhaps surprising trend that has been noticed is that a number of them took (and, to some extent, take) active part in promoting new and experimental composition. In Chapter 8 below, for example, Carol J. Oja explores in detail the ways in which a small number of individual wealthy women in New York in the 1920s, including Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney (better known today for her art patronage) and Alma Morgenthau Wertheim, supported the composers of new or "modernist" music such as Henry Cowell and the young Aaron Copland: they opened their homes and purses to the composers, just as they, or women very much like them, did to struggling modern painters and poets. Indeed, it has been suggested by Sandra M. Gilbert and Susan Gubar (in regard to literature), Kathleen D. McCarthy (visual art), and Catherine Parsons Smith (music) that the avant-garde provided a forum in which women could exert productive influence, as opposed to more mainstream cultural institutions, which tended to be dominated by male patrons and directors. In the case of visual art, in particular, new work had the advantage of being "relatively inexpensive compared to the prices that men like [J. Pierpont] Morgan [and art museums, largely run and funded by men,] were willing—and able—to pay for the master-pieces that they so avidly pursued."[63] Similar economic advantages may have been at work in music: Alma Wertheim could help bring to performance or publication a dozen modern chamber works, or keep their needy composers fed, for less than the cost of building a concert hall or running a symphony orchestra.

Indeed, the wealthy "individualist" woman patron of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries did not often make huge donations on her own, in the manner of Otto Kahn at the Metropolitan Opera or Henry Lee Higginson, founder of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, or Edward J. De Coppet, the creator and sustainer of the Flonzaley Quartet. Some of this may have been, again, economic, in that even a wealthy woman such as Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney controlled far less money than her husband. (The many concert halls named after

women are generally of more recent vintage, the result, in large part, of family estates eventually reaching the hands of music-loving women.)

More typically, the "individualist" patron of the turn of the century opened her home to musical and artistic gatherings, in imitation perhaps of famed European salons;[64] turn-of-the-century examples of musical salons included the homes, in Boston alone, of Isabella Stewart Gardner, the poet Amy Lowell, the painter Sara Choate Sears (whose husband Joshua Montgomery Sears was an amateur violinist and reportedly the wealthiest man in the city), Sarah Bull (widow of Ole Bull), and the composers Amy Beach and Clara Kathleen Rogers. To be fair, some men hosted musical soirées, too, such as the music critic William Foster Apthorp. Such "house concerts" became prominent toward the end of the nineteenth century, when the great American family fortunes first began to build up and when (as noted earlier) changes in various state legal codes permitted more and more women to manage and freely disburse their own money. "House concerts" form a whole hidden, because private, stream of high-level music making: Nellie Melba, Paderewski, and Fritz Kreisler were among the favored performers. Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge, in addition to sponsoring public concerts throughout the United States (and abroad), hosted more private ones in her splendid Pittsfield music room (see Chapter 6); analogous events took place in Blanche Walton's house in New York (see Chapter 8). More recent and particularly imaginative are the performances and talks by a single composer such as John Cage or Steve Reich before an influential group of guests—each evening similar to the opening of a "one-artist show" in the art world—that Betty Freeman has mounted in her home in Los Angeles. (See Vignette B.)

McCarthy's other two categories of women's organizations—"separatist" and "assimilationist"—can also be seen in the efforts of women in American music, especially if one reinterprets these categories as being not discrete boxes but rather two ends of a continuum. Linda Whitesitt has in several articles documented the work of women's music clubs. These clubs, at least originally, consisted of women gathering together to encourage one another to make (in this case) music at home or at modest, semipublic recitals. Thus, in their "separation," they paralleled in origin and function various general-purpose women's clubs and women-only societies for the decorative arts.[65]

Closely allied to these, but perhaps halfway along the continuum toward McCarthy's third category, "assimilationism," are the "women's committees" of symphony orchestras, opera companies, and recital series. Ever since its inception under the intrepid Mrs. Belmont in the 1903s, for example, the Metropolitan Opera Guild has had one foot firmly in the separatist and the other in the assimilationist camp: the guild involves a group of women devoting much time to gathering smallish donations from a largish number of contributors (a typical feature of many "separatist" organizations in the arts), but these contributors include men as well as women (a feature more typical of "assimilationist" organizations).[66]

The Met Guild and the "symphony ladies" in every major (and many a minor)

American city hold a position that may strike us as contradictory or as a latent source of tension. They often raise—and raised, but for the moment we prefer the present tense—needed funds, and they encourage subscriptions (through various combinations of charm and guilt-inducing tactics, we are told). Nonetheless, the decision-making power remains vested in an all- or mostly male board of trustees or guarantors. Such a division of labor at least has the advantage of relatively clear boundaries. (The "relatively" allows for many exceptions, especially in the past: an astutely observant novel by the music critic W.J. Henderson, The Soul of a Tenor , reports—and we see no reason to discount it—that women patrons of the opera in turn-of-the-century New York made meddlesome suggestions as to casting, costumes, and staging.)[67]

More mysterious is the case of those women who, in full "assimilationist" fashion, actually sit on such boards—an increasing number in recent decades—or who take part in joint (male and female) music clubs and organizations (an early example being the Macdowell Clubs in certain cities, such as New York, or the various Manuscript Clubs, such as the one organized by Mary Carr Moore in Los Angeles). An interesting study could surely be made, focusing on such questions as: Do these women have different reasons for being active than the women on "ladies' committees" and in women's music clubs? To what extent are the same women—especially some of the most energetic and devoted—often active in all of these different sorts of organizations?[68] Is board membership the eventual reward for good work on the "ladies' committee," or are board members—female as well as male—chosen primarily for their financial clout and business connections? And are women, once they are allowed a place on mixed-gender institutional boards, granted the kinds of leadership opportunities and responsibilities that have long been part of the challenge of working in women-only groups?[69]

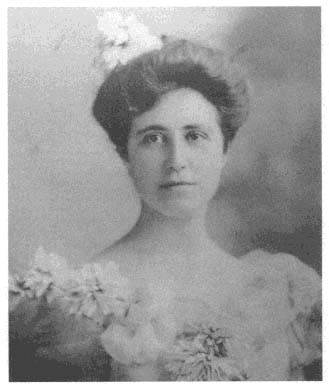

The challenges—and opportunities—of volunteer work on behalf of music are precisely the sorts of things that remain concealed by the unfortunate, if sometimes affectionately offered, stereotypes of women volunteers as silly geese in flowered hats. What Anne Firor Scott has discovered over and over again of women's aid-to-orphans associations and the like is no doubt equally true of these various music clubs and committees: through them, generations of women have "learned how to conduct business, carry on meetings, speak in public, manage money."[70] Scott's phrasing here is a touch categorical—many bourgeois women no doubt handled financial affairs in the home—but her main point holds. Indeed, some of the music clubs' "organizational genius[es]"—as one club member described such reins-taking types in an address to the 1893 National Convention of Women's Amateur Musical Clubs[71] —went on to become music administrators and concert managers for pay , as musical life became more professional and bureaucratic. An early example is Adella Prentiss Hughes (fig. 1), a member of Cleveland's Fortnightly Musical Club who turned the club into a major sponsoring agency of concerts by visiting soloists and orchestras and who eventually founded the Cleveland Orchestra (1918) and served as its much-respected manager until 1933. The

Fig. 1.

Adella Prentiss Hughes (ca. 1908), a charter member of

Cleveland's Fortnightly Musical Club and one of

the founders of the Cleveland Orchestra.

Reproduced by permission of the

Western Reserve Historical Society.

composer-conductor Victor Herbert, who led the Pittsburgh Orchestra from 1898 to 1904, said that Hughes "knew more about the business of music than anyone I ever knew" and declared, "I would rather have her for my manager than any man in the world."[72]

Several other aspects of American music patronage seem remarkable precisely in ways that McCarthy's categories do not address. In Chapter 7 below, on women musicians and patrons in the African-American communities of Washington, D.C., and other cities, Doris McGinty draws attention to a number of distinctive features of musical life and patronage in such communities, including the central position of choral singing, and also deals with women who, to a certain extent, did make a modest living from the work they did in music. This seemed a necessary adjustment in our criteria about what comprises a "patron," in that substantial numbers of women of wealth were not available in the communities McGinty discusses. It also, though, may serve as a convenient reminder that, as noted earlier, the patrons and organizers of music in America have ever included (and in the

early years of the republic consisted almost entirely of) the musicians themselves, working at low pay, or even losing money on their ventures for the sake of the art in which they believed.

Or take Joseph Horowitz's description in Chapter 5 of how the author and newspaper editor Laura Langford and an all-female crowd of volunteers brought live performances of Parsifal and other Wagner works to New York and Brooklyn, often at low prices, under the inspired baton of Anton Seidl. Since the enthusiastic audiences, too, were heavily female, one begins to doubt whether "assimilationist" is the right word. Emanuel Rubin reports in Chapter 4, in greater detail than has been known before, on the ways in which Jeannette Thurber tried to build a democratic and pluralistic musical life in America, not least through coast-to-coast tours of her American Opera Company singing in English, but also through the National Conservatory, which she founded in New York, with Antonín Dvorak[*] as director, and for which she valiantly, although in vain, sought support from Congress. Here is an early case of a woman as (unpaid, indeed paying) arts administrator and lobbyist, almost as Lone Ranger, again not clearly analogous to McCarthy's often cowed women on museum boards. And Sophie Drinker, as Ruth A. Solie shows in Chapter 9, transformed herself into a pathbreaking feminist scholar (although, intrigumgly, one whose general political position remained quite conservative) in response to frustration: Searching on behalf of an amateur women's chorus in which she sang, she realized that there existed little published music by women composers. All these chapters, as well as the interchapter vignettes, give evidence that women's support of musical life in America has been extensive (far more than our music histories even hint at) and also varied—remarkably and sometimes puzzlingly so—in aim, scope, and effect.

The Woman Musician and Woman Patron Today

The state of live music making in the recent past and today (again, in the "classical" realm) presents a complicated and contradictory picture, involving both contraction and expansion on several fronts. The percentage of people making their living in music (any kind of music, apparently) has decreased greatly since the turn of the century, hovering now around 0.5 percent, with women representing a higher percentage of people involved in music education (predictably) than in performance, much less composition. The decline of piano and other one-on-one musical instruction surely accounts for much of the drop. This decline in employment, however, was at least somewhat moderated by a significant increase in the number of stable professional ensembles (and in the length of their playing season), especially during the 1960s and 1970s, when arts-center complexes were established in most major and many middle-size cities, thanks to funds from corporate foundations, the National Endowment for the Arts, and city, county, and state government. Throughout the decades, throngs of women volunteers have continued to carry out much-needed assignments on behalf of these ensembles, concert

series, and the like, especially in the areas of fundraising and educational outreach. But reports have it that their numbers are decreasing, perhaps in more or less direct proportion to the move of educated women into the workplace, whether that be a matter of choice or necessity (or some combination of the two).[73]

For some, of course, the workplace is now music. In all but the few most distinguished American orchestras, women and men fill the seats on stage in proportions so close to equal that the issue of a player's gender no longer seems significant to most people in the audience, or to the orchestra's management. (Indeed, in the interests of equal opportunity, candidates auditioning for an orchestra position are generally required to play from behind a screen, often in stocking feet to avoid the telltale click of high heels.) We are even beginning to see women breaking the barriers that kept them out of particularly male-identified job slots: not just as player of those various "men's" instruments mentioned earlier but also as concertmaster (i.e., the leader of the violins), visiting clarinet or trumpet virtuoso, all-commanding conductor (e.g., Sarah Caldwell, Marin Alsop, JoAnn Falletta), honored composer (e.g., Ellen Taafe Zwilich, Joan Tower, Libby Larsen, and the late Louise Talma and Miriam Gideon), and, yes, even that ultimate "guy's job," college-band director.[74]

Such direct and welcome involvement in the creative and re-creative process has also been accompanied by women's continuing involvement in administering and merchandising musical performance, activities for which they once volunteered their services but are sometimes now paid. In cities across the country (e.g., Chicago, Miami), the arts "presenters" at cultural centers are disproportionately female; indeed, one finds all sorts of gender mixtures in arts administration: an insightful column by Calvin Trillin describes a Louisiana concert series run by a program director who is male and unpaid (and who makes his living in other fields), assisted by an executive director who is female and receives a regular salary.[75] Many prominent artists' managers are also women (e.g., Ann Colbert, Edna Landau, Thea Dispeker).

In the world of orchestras, too, women have made notable business careers. Joan Briccetti holds the position of orchestra manager at the St. Louis Symphony. The manager is "the number two person," as Briccetti put it in a recent interview, in an orchestra's administration. Briccetti notes with regret that the orchestra's executive director (i.e., the number-one person, sometimes called the "general director") still tends to be personally selected by "the entrenched leaders of the community" on the board of directors; no doubt for that reason, the position, like that of bank president or hospital chief, still remains largely off-limits to women. But that may be changing, too: Deborah Borda has held the top spot at the New York Philharmonic since 1987. And even in the highly exposed field of music criticism, a few women—the pioneering Claudia Cassidy and, more recently, Shirley Fleming, Nancy Malitz, the late Karen Monson, and the unstintingly opinionated Manuela Holterhoff (music critic of the Wall Street Journal )—have risen to positions of influence and healthy notoriety.[76]

This rise of the woman professional in music coincided with and was facilitated

by the expansion in our musical institutions that occurred roughly between 1950 and 1990. The current climate, by contrast, is one of ceaseless contraction. Government and foundation money is receding almost daily, arts coverage in newspapers and magazines is drying up, and members of the educated middle and upper classes—that traditional pool of potential concertgoers, donors, and volunteers—are moving deeper into the suburbs and losing, or (in the case of the younger ones) not developing, the habit of traveling back downtown, where concert halls and theaters are generally located.[77] The result is that arts organizations are having to make hard choices, and the options are all unpleasant.[78] (Additional technological factors in this crisis have been noted above; their implications for the future are discussed at the end of Chapter 10.) Orchestras and opera companies may feel pressure to reduce the number of concerts or operas in a season, effectively cutting the players' pay, which is generally based on number of "services" (i.e., rehearsals, performances, and recording sessions). Or they may be tempted to lower the players' wages per "service" without reducing their performing duties, thus undercutting some of the gains hard-won by the musicians' unions (although with luck the musicians will demand in exchange more of a voice in matters of policy and programming—as recently occurred with the Denver Symphony—and, with more luck, will use their influence wisely). The orchestras' managers and governing boards can also refuse to program unfamiliar or difficult modern works that require extra rehearsals or that may scare away subscribers whose dollars they cannot afford to lose. ("We baby boomers," one arts-center administrator notes, "are not subscribers. We were brought up in a world of choices. . . . [But this] loss of subscriptions forces you into more mainstream programming.")[79]

The orchestras may also find that they can no longer afford to make recordings, go on tour to New York or to small cities in their own region, or schedule as many outreach concerts as they used to for schoolchildren, however important such activities are for the players' self-esteem and for the community's sense of involvement in, "ownership" of, its orchestra. Those who hold the purse strings may feel compelled to trim the orchestra to a "core" number of players barely adequate for playing Beethoven and Schumann, and rely on "ringers" (i.e., part-time players, often less experienced) if and when the budget allows an occasional Bruckner or Mahler symphony, the requiems of Berlioz, Verdi, Brahms, or Britten, or a concert version of, say, Die Walküre (not an ideal way to encounter Wagner, but a clear desideratum given many cities' lack of good, stable opera companies).[80] They may play more concerts in suburban high-school auditoriums and churches, where the under- or overresonant acoustics end up killing everybody's pleasure in the music (including that of the musicians themselves). And they may find themselves diverting ever more funds to an increasingly large and professional marketing staff, enamored of listener surveys, superstar names, and glossy brochures full of prose puffery and/or zippy (sometimes sexy) pictures.

Most discouraging, an orchestra's board and administration may find that they have undertaken not one but several or all of these cost-saving and audience-

baiting maneuvers and still find themselves continuing to run up big deficits, as listeners turn away to forms of leisure activity that are less demanding aesthetically and intellectually. (Art-music administrators and presenters are not alone: producers of films of a consciously artistic or experimental nature, publishers of poetry of almost any sort, and theater directors seeking an audience for drama that seeks to do more than entertain are caught in a similar bind.)

Several alternatives remain for art-music organizations, including the obvious ones of making the programming more attractive without watering it down (e.g., organizing concerts around a topic or theme, a current success story, we are told, at the San Francisco Symphony and the American Symphony) or finding new hours for concerts, such as early-evening events that catch commuters before they leave downtown. But a many-sided problem is likely to require a many-sided solution. And so the well-tested method of enlisting the energies and mobilizing the devotion and imagination of music lovers—whether the wealthy few or the merely "comfortable" many—surely remains a major ingredient in the recipe for solvency at most of America's musical institutions.

To be sure, female music lovers, as we said, tend to be less available for volunteer work now than in the past, and males seem not to be taking up the slack in appreciable numbers. (The rise in volunteerism at social agencies, such as child-abuse "hot lines," may also explain some of the decline at arts organizations.) The pinch is being felt in direct financial contributions as well, and disproportionately so in music compared to the other arts: Tom Wolfe, a consultant to the American Symphony Orchestra League, estimates that the portion of all arts giving that went to orchestras fell by about a third between 1970 and 1990.[81] Still, many women control substantial sums of money in this country (surely more, proportionally, than at the beginning of the century), and women continue to volunteer their efforts and time for a wide range of causes far more than men do.[82] The phenomenon of the woman volunteer and patron—the female "activist"—remains central to the nonprofit, "classical" wing of America's musical life, as chapters yet unwritten will surely someday record.

Vignette A—

Women and Church Organs:

1830s–1860s

Documents with Commentary by Stephen L. Pinel

Over the course of the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, many areas of American music experienced a struggle between primarily "vernacular" styles and genres and more "cultivated" ones.[1] As the present documents reveal, women were actively involved in establishing the new, "cultivated" type of music in local churches. (This is not to say, however, that women were not just as actively involved in trying to maintain more "vernacular" traditions of sacred singing in other towns and situations.) Indeed, women also, as these accounts repeatedly make clear, often were the church organists, or at least filled that function from time to time, without pay, or for longer periods if a professionally trained male organist was not available or could not be afforded.

In the colonial and federal periods, Protestant sacred music in America had consisted primarily of simple hymn singing, often done without instrumental accompaniment: the leader would call or sing out the first line, the congregation would repeat, or respond with a refrain, and so on. This practice, which derived from the music of the English parish church and had its roots to some extent in English folksinging, often combined with slow tempos to give rise to elaborate ornamentation, scoops, and so on, by both leader and congregation, tendencies that became quite extreme in the folk-song-influenced revivalist hymns of the early nineteenth century. Church music reformers such as Lowell Mason (1792–1872) strove to stamp out such unregulated improvisatory practices and to replace them with a "chaste" and "correct" manner of singing hymns, understood as entailing a strict adherence to the notated meter and pitches, and a prominent and correctly harmonized setting, often doubled by an organ. Aspects of the more erratic and spontaneous "old style of singing" survived in small towns in the South and Midwest, and derivations of it can be heard even today in performances by "shape-note" (e.g., Sacred Harp) and gospel choirs, whether white or African-American. But the mainline churches in the Northeast eagerly welcomed the new and more decorous style of worship and also the organs, diversely symbolic in their floor-shaking grandeur, conspicuous ornamentation, and well-advertised costliness.[2]

The following accounts of the funding of five new church organs (and the repair of a sixth) in mid-nineteenth-century New York State and Pennsylvania give some sense of the community pride that was stirred by the arrival of a big-city organ builder in towns that still had something of a rural air. (Honesdale, Pennsylvania, lies between Scranton and the corner where the state meets New Jersey and New York Hudson, New York, is on the river of the same name, about halfway between Kingston and Albany.) Many of the organ builders were located in Boston or, as in the present cases, New York City, and they often stemmed from a German émigré family, as was the case with Henry Erben, the builder of the first organ in Hudson (1838).

Levi U. Stuart furnished three other organs mentioned here: Hudson's third organ (1867) and the two in Honesdale (1868). The latter were installed by his brother, William J. Stuart.

Although the choice of a builder and of the organ's design and placement was presumably made in most cases by males—the elders of the church—the funds seem frequently to have been raised by women parishioners. (Many such cases are mentioned in diocesan convention reports of the Episcopal church.) At Hudson's First Reformed Protestant Church, the very initiative for installing an organ came from "the ladies," and their insistence is notable: they even succeeded in overriding the initial opposition of the church's leadership on this matter, in part by gaining the support of younger pew holders, most of them presumably male. Interestingly, the church's official history, written by its pastor in the 1880s, notes that one woman's attempt to establish a Sabbath School was similarly resisted: "not a few" in the church "discouraged her, regarding it as an unwise project and an experiment which was sure to fail."[3] We also learn that half the salary of the first paid organist was contributed by private members of the church, perhaps including some of the same music-loving women. The second and third organs, and their organists, seem not to hare required special private donations, perhaps because the church had grown so in size and, as the historian-pastor notes, also in "resources" and "prosperity."

Excerpt from the Official History of the First Reformed Protestant Church, Hudson, N.Y.

Rev. William H. Gleason, D.D., Pastor

During the year 1838 the ladies of the church brought forward a project for the purchase of an organ, and with this came into it [i.e., the church] the only dissension which appeared during the entire period of its work of organization. There was an element of Scotch Presbyterianism in the church which was opposed to the instrument from principle. There was another conservative element which regarded the movement as premature from an economical standpoint. The first application for consent to place it in the church was denied by the consistory, but the ladies secured the names of sixty pewholders to a second application, and backed by the enthusiasm of the younger part of the church obtained a reversal of the decision by one vote. This action led to the resignation of one of the elders and two of the deacons and their withdrawal from the church. The two lat[t]er after a time returned to its worship, the former transferred his connection to the church of Claverack.

The organ was purchased of Henry Erben & Co., of New York, at a cost of one thousand dollars. Of this amount four hundred dollars were the proceeds of a fair held in the long room of the hotel of Abram Staats, now the Central House, a room which was then as generally used for all public meetings as is the City Hall to-day. This is believed to have been the second fair held in this city. The first is said to have been held in 1835, by the Universalist Society in the private ballroom of Robert Le Roy Livingston in his mansion, since converted into the Waldron House. The balance of the money [for the organ] was raised by subscription and the proceeds of a concert given in the church after the erection of the organ, at which Rev. Isaac Pardee, of the Episcopal church of this city, gave an address upon sacred music. At this concert Mr. [Enoch S.] Hubbard, accompanying himself upon

the violin, sang the solo entitled "Consider the Lillies [sic ]," quite well known to-day but then heard for the first time in Hudson. The organ was of small capacity but sweet in tone, and gave great satisfaction. After its introduction all feeling of dissatisfaction disappeared, and perfect harmony was restored with a single exception. One member of Scotch descent was dissatisfied with preludes and interludes, and finally left the church service upon the introduction of the well-known and popular tune, "Antioch," which he denounced as "no better than an Irish jig." The duties of organist were shared by Miss Mary Miller and Julia A. Shufelt, now Mrs. Alexander S. Rowley, without pay, until the engagement of Prof. Francis S. Blanchard in the month of November, 1840, Mr. Hubbard retiring and Mr. Wynkoop for a short period assisting Mr. Blanchard, one half of whose compensation was to be raised by private subscription. Full charge was soon given the latter, who continued faithfully to serve the church, with the exception of two brief intervals, for the period of thirty-five years. . . .

An exchange of organs followed the enlargement of the church, the organ in use giving place to one of much greater power and much less sweetness of tone, at a cost of about one thousand four hundred dollars added to the value of the old organ. . . .

[In 1867 the church was again reconstructed, and] an effort was made looking to the placing of a third new organ in the church, which resulted in the purchase of the instrument now in use. It was built by Mr. L. U. Stuart, of New York, at a cost of two thousand and forty-six dollars added to the value of the instrument then in use, which was estimated at one thousand dollars. It did not prove on its completion acceptable to the church, and to the sums mentioned, about three hundred and thirty dollars additional were paid for an alteration which it was hoped would make it so. Its first use was on the evening of October 6th, 1868, in a concert given by Mr. George Morgan of New York, an organist of great reputation.

With increased accommodation came increased resources and benevolence, and for years the church enjoyed the highest degree of prosperity it has yet reached.[4]

Honesdale, Pennsylvania, seems to have been a more modest place: no mention of mansions with ballrooms here. Yet in Honesdale, too, the women took the lead in musical "progress," as it was then understood. In a manner consistent with women's generally domestic role, the female parishioners of Honesdale took to the kitchen and held "organ suppers." In the case of the Presbyterian church, one notes from a report of 25 June 1868, below, that funds were still being raised at yet another organ supper several weeks after earlier newspaper accounts had announced that the gift of the organ was complete, indeed even after the organ had been installed and dedicated.

Also notable is the fact that the organ builder's representative, rather like a traveling salesman or country doctor, serviced three churches in Honesdale before moving on. The three churches mentioned in the newspaper reports from Honesdale are St. John's (Catholic), First Presbyterian, and Grace Church (Episcopal).

These three churches were in different circumstances with regard to their organs. St. Johns's simply sought to repair the existing instrument. Grace Church bought the new Stuart to take the place of their old organ