20—

Undermining the Body Politic (Book V)

Pathology of the Body Politic

The illustrations for Book V of the Politiques (Figs. 67 and 68) are the third of a series concerned with means of preserving or undermining political systems. The underlying theme is the metaphor of the health or disease of the body politic. Unlike the illustrations of Book IV, the set of miniatures for Book V relies on visual definitions, which serve as invented exempla of the paradigmatic representational mode. Although Oresme's program continues the two-register format of the illustrations for Books III and IV, here he employs the visual structure for narrative and dramatic ends.

The text of Book V provides the basis for such a dramatic treatment. The subject is what Ross calls the "pathology of the state," since Aristotle plays the role of a physician in "diagnosing the causes and in prescribing the cure for the diseases of the body politic." Book V discusses the causes of revolution and the means of preventing it in both good and corrupt regimes.[1] Enhanced by a wealth of examples drawn from Greek history, Aristotle's practical treatment of the means of preserving even the most corrupt regimes from revolution has led scholars to consider Book V as an ancestor or model of Machiavelli's The Prince .[2] Within the context of the causes of sedition, Oresme's commentary on the fourth chapter of Book V discusses the tradition of the concept of the body politic.[3]

Formal Aspects of Figures 67 and 68

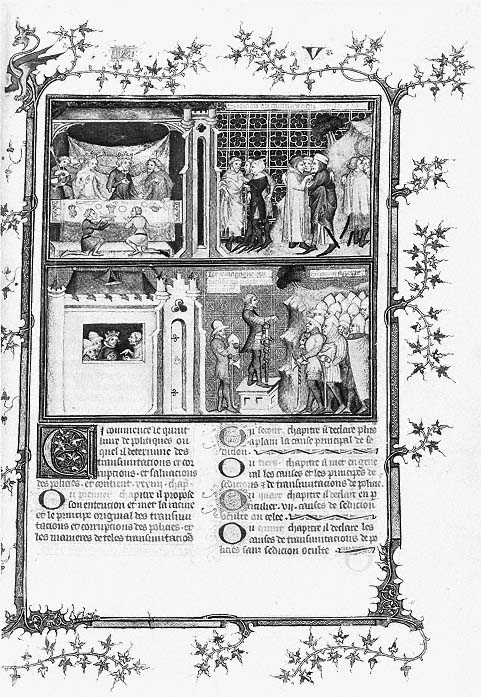

To realize Oresme's program for the updated and concrete presentation of the dramatic subject of revolution, the illuminators had to enlarge their visual vocabulary. In one of his most accomplished miniatures (Fig. 67), the Master of Jean de Sy constructs for the first time in the cycle elaborate internal architectural settings and an abbreviated landscape background. The challenge of representing verbal and emotional interplay among different social groups suits his fluent figure style. Animated gestures, varied postures, and individualized facial expressions enliven the scenes. The miniature occupies two-thirds of the folio.

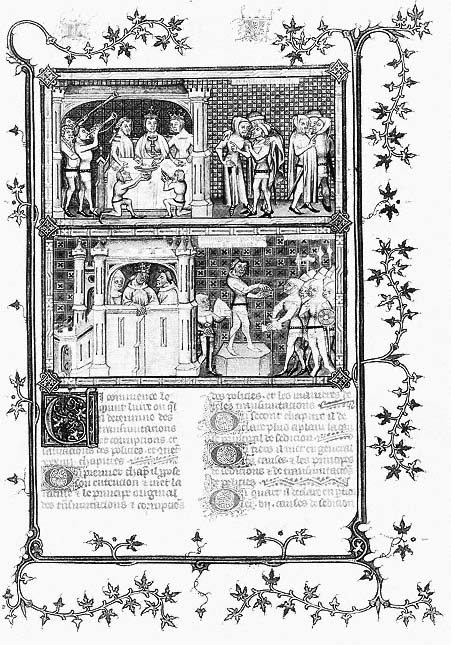

The same mise-en-page is followed in Figure 68. Executed by a member of the workshop of the Master of the Coronation Book of Charles V, in dimensions

Figure 67

Above : Sedition ou Conspiracion occulte; below : Le Demagogue qui presche au peuple contre

le prince, Sedition apperte. Les politiques d'Aristote, MS B.

Figure 68

Above: Conspiracion occulte; below : Demagogue preschant contre le prince, Sedition

apperte. Les politiques d'Aristote, MS D.

and layout this miniature replicates the proportional relationship of image to text of Figure 67. Yet within this consistent pattern several elements mark an elaboration of the miniature. Although the figures are modeled in the usual grisaille technique, color differentiates parts of the architectural setting, such as the green gate, red roof, and blue turrets. Gold is also visible in the table furnishings, crowns, and musical instruments. White and black take on important roles in delineating key areas such as the tablecloth or the armor, belts, and shoes of military uniforms. One exceptional feature that appears for the first time in this cycle is the bold exterior frame that surrounds the miniature and divides the two registers. Several elements of the enframement are fashioned in gold: the thin outer band and the six diamond-shaped lozenges embossed with trefoils. The most conspicuous feature is the wider inner band decorated with zigzags and alternating vertical and horizontal geometric motifs painted in pink and white on the upper register and in black and white on the lower one. Altogether the effect enhances the existence of each scene as a separate entity and emphasizes its three-dimensional aspect. Despite these enrichments of Figure 68, certain reductions are evident in comparison to similar elements in Figure 67. For one thing, landscape features are entirely eliminated. Architectural elements, numbers and groups of figures, and certain accessories, such as the tableware, are simplified and reduced in size. Despite these changes and the dryness of the illuminator's style, the expressive character of the miniature remains intact.

The Verbal Definitions

The summary paragraph directly below Figures 67 and 68 immediately alerts the astute reader to the dramatic content of Book V: "Ci commence le quint livre ouquel il determine des transmutations et salvations et corruptions des policies. Et contient .xxxiiii. chapitres" (Here begins the fifth book in which he ascertains the changes and corruptions and salvations of governments; it contains thirty-four chapters).[4] Oresme emphasizes two important themes: the transformation of the forms of government and their corruption. To understand Aristotle's discussion of the processes by which such changes take place, Oresme offers the reader a detailed series of verbal aids. The first clue is the inscription found just below the top of the upper register. Figure 67 gives a double definition, "Sedition ou conspiracion occulte" (sedition or hidden conspiracy), while Figure 68 uses the second phrase only. The neologism sedition appears immediately below the miniatures in the headings for Chapters 2, 3, and 4. In a gloss on the first chapter of Book V Oresme defines the term by a series of synonyms: "Sedition, si comme il me semble, est conspiration ou conjuration ou commotion ou division ou dissention ou rebellion occulte ou manifeste d'un membre ou partie de la cité ou de la communité politique contre une autre partie" (Sedition, as it appears to me, is a conspiracy or plot or disturbance or division or dissension or rebellion—hidden or open—by a member or part of the city or political community against another part).[5] Oresme includes definitions of sedition in both the index of noteworthy

subjects and the glossary of difficult words.[6] Indeed, the latter uses the exact words such as conspiration occulte and sedition aperte (open sedition) that appear in the inscriptions of the upper and lower registers respectively.

The inscription on the lower right of Figure 67 reads: "Le demagogue qui presche au peuple contre le prince" (The demagogue who rails against the prince). In Figure 68 the phrase is shorter: "Demagogue preschant contre le prince." The neologism demagogue does not appear in the chapter headings, but it does figure in the index of noteworthy subjects and the glossary. Oresme defines it in the latter place: "Demagogue est qui par adulation ou flaterie demeine le menu peuple a sa volenté et qui les esmeut a rebellion contre les princes ou le prince" (A demagogue is one who by false praise or flattery excites the populace to rebellion against princes or the prince).[7]

Visual Definitions and Visual Structure

The programs of Figures 67 and 68 clearly function as updated and concrete visual definitions of key terms such as sedition, conspiracion , and demagogue . The visual structure offers a close fit with the paradigmatic representational mode, the definitions, and their textual amplification. To begin with, the two-register format permits division of the picture field into two separate units that organize the action sequentially and chronologically. Within each unit, lateral subdivision into interior and exterior areas represents simultaneous action. The initiators or agents are depicted in the right half of the scene; the objects of the actions, in the left.

On the upper left, a royal meal takes place within the cutaway walls of a palace banqueting hall. Flanked by a male companion and a queen, a king in the center is drinking from a goblet. (The queen is the only female figure represented in the eight miniatures of the Politiques cycle.) Three musicians play while two kneeling servants offer food. The sumptuous gold curtain behind the table accentuates the luxurious character of the repast. The expressions of the royal couple and the gesture of their companion who points to the right reveal an awareness of the conspiracion occulte . In Figure 67 an open portal leads to the outside where a hill is crowned by a clump of trees and where three groups of figures in civilian dress converse. All three men on the left point toward the palace door, toward which two are walking. Locked in a circle defined by the arms of the man in the middle, the three face-to-face figures of the closely knit central group engage in earnest conversation. The fragmentary group on the right is also united in an embrace. In Figure 68, the same arrangement of figures appears within a more simplified palace interior. Here, however, only two groups of figures converse on the right, and the specific landscape setting is eliminated. Both figures represent an enactment of sedition and secret conspiracy against a royal regime. In fact, the action of the figures on the right carries out another part of Oresme's definition of these terms: "Et avient communelment que murmure precede sedition" (And whispering generally occurs before sedition breaks out).[8]

The lower register of Figures 67 and 68 represents a second phase of the conspiracy, sedition apperte . The left half of the register indicates a transmutacion of regime. In another room within the castle seen from above, the bust-length figure of the king of the upper register is visible through a small rectangular pictorial opening of a solid wall. The door of the castle is now shut. The two helmeted soldiers on the left and the gesturing figure on the right suggest that the king is now a prisoner. In Figure 68 the imprisonment of the king is even more clearly represented than in Figure 67. The former scene shows the king in a frontal position; his crossed hands suggest resignation or acceptance of his new situation.[9] The discussion that takes place in Figure 67 between him and his military and civilian guards gives way in Figure 68 to wary surveillance. The transfer of the closed portal and gateway from the right to the left emphasizes the isolation of the imprisoned ruler from the military force outside the castle walls.

On the right of Figures 67 and 68 the apparent agent of the change of regime is the "demagogue qui presche au peuple contre le prince." The groups of civilian conspirators of the upper register yield to one armed leader. Accompanied by an aide who holds his helmet, he stands on a rostrum addressing his audience. The full-length figure and profile head of the demagogue in Figure 67 display a confidence conveyed by his sword and the gesture of his outstretched arm. His audience is dramatically grouped within the rocky landscape setting. Also standing (mostly) in profile, their expressions and gestures indicate their rapt attention to his address. The profile view of speaker and audience is part of a gestural code that associates it with low social status and irresponsibility or treachery.[10] The armor, helmets, and shields that the demagogue and his listeners wear indicate that a military coup d'état is under way or about to take place.

As in the illustrations of Books III and IV, the visual structure of Figures 67 and 68 again employs parallelism and contrast of the upper and lower registers. The program for Book V, however, contains novel narrative elements derived partly from the definitions. The extensive architectural settings and the landscape in Figure 67 reinforce associations with the respective political antagonists. The castle is a visual metaphor of the monarchic regime in which power is located. More specifically, Oresme's program suggests the rhetorical figure of synecdoche, in which the part stands for the whole of a conceptual relationship.[11] The exterior setting in which the sedition takes place presents a similar figure for those who stand outside, or divided from, the political regime.

The two-register format also indicates a temporal sequence, as the hidden conspiracy of the upper register gives way to the open rebellion and transfer of power to the conspirators in the lower. Several references to time derive from the forms of the definitions: hidden and open conspiracy or sedition; whispering preceding sedition; and the demagogue preaching against the prince. Parallel settings establish an ironic contrast in terms of the "ins" and "outs" who hold political power. In the left half of the upper register, those inside the banquet hall exercise sovereignty. Directly below this scene the castle becomes a prison for the prince, who is now "out." Conversely, the "outsiders" on the upper right become the "insiders" of the lower right with respect to holding political power. In addition, the

lateral division of each register also permits a cause-and-effect relationship between the actions and actors of the left and right halves of the miniatures. Costumes and gestures reinforce the contrasts and parallelism of the visual structures. Oresme's program fashions a fictive exemplum of the paradigm enunciated in the generic verbal definitions.

The Appeal to Historical Experience

The programs of Figures 67 and 68 could certainly recall to their primary audience the formative historical experiences of the present regime. Oresme's selection of the themes of sedition and demagoguery as they affect kingdoms, and not the other systems of government, reflects a conscious attempt to raise associations with contemporary political events. To be sure, the miniatures do not permit specific identification of the ruler as either king or tyrant. Indeed, Oresme may have intended that the distinction remain ambiguous in view of Aristotle's discussion in the Politics (Book V, Chs. 21 and 22) on the corruption of monarchy and its transformation to tyranny.[12] The banquet scenes emphasize the dangers to rulers of secret plots or conspiracies. Oresme may be alluding to Aristotle's statement that rulers tend to be corrupted by excessive wealth.[13] Accumulations of riches and honors invite the envy of subjects and are the source of sedition. Aristotle further points out that in hereditary monarchies kings may indulge themselves in bodily pleasures at the expense of their responsibilities to their people:

T. Mes es royalmes qui sunt selon lignage, ovec les choses qui sunt dictes il convient mettre une autre cause de corruption. Et est ceste: que pluseurs telz roys sunt faiz de legier contemptibles et despitablez. (T. But in hereditary kingdoms, in addition to things already mentioned, it is necessary to set out another cause of corruption. And it is this: that several such kings readily merit contempt and scorn.) G. Pource que il vivent trop delicieusement et sunt negligens si comme il fut dit ou .xxii.e chapitre. (G. That is because they live too much for pleasure and are negligent, as was stated in the twenty-second chapter.)[14]

Perhaps certain features of the upper left scene of Figures 67 and 68 allude to the types of excessive expenditure that corrupt and endanger hereditary kingdoms. In Figure 67 particularly, the elaborate feast, gold curtain, and musicians indicate such dangers. Figure 68, however, may depict another type of threat to hereditary kingdoms. There the companion of the royal couple wears a mantle whose distinctive fur strips indicate a member of the royal family.[15] In a gloss at the beginning of Chapter 24, Oresme mentions sedition provoked by a person already taking part in government: "Si comme quant aucuns du lignage du roy ou autres grans seigneurs de son royalme funt conspirations contre lui" (As when some persons of the king's lineage or other great lords of his kingdom conspire against him).[16]

Figure 69

A Royal Banquet. Avis au roys.

Charles V and his counsellors were personally aware of the dangers of sedition fomented by a close relative. During the political crisis of 1358–60, Charles's brother-in-law, Charles of Navarre, known as the Bad, contested the regent's claim to the throne.[17] In 1356 the alliance of Etienne Marcel with Charles the Bad almost cost the regent his future throne and his life.[18] Furthermore, in the context of Sedition apperte the scene of a demagogue addressing his troops might well recall to Charles V the plots of Etienne Marcel and Charles the Bad. As a way of updating the definition of a demagogue in the glossary, Oresme cites as an example the earlier fourteenth-century bourgeois leader, Jacques d'Artevelde.[19]

The immediacy of historical recollection offered in Figures 67 and 68 to its primary audience may have formed part of Oresme's strategy in designing the program of Book V. While the total visual structure of the illustrations contains novel elements, individual sections rely on standard iconographic types. For example, the banquet scene of the upper left is familiar from a wide variety of medieval secular and religious visual and textual sources, including a miniature from the Morgan Avis au roys (Fig. 69). The scene of the demagogue addressing the troops adopts the Roman iconographic theme of adlocutio .[20]

In addition to the dimension of historical experience, Oresme's program for the illustrations of Book V incorporates another didactic level. Oresme refers in several glosses to Aristotle's discussion in the Rhetoric of anger and hate as motives for the overthrow of kingdoms and tyrannies.[21] Oresme thus may have intended

Figures 67 and 68 as a warning to his readers to avoid such patterns of dangerous conduct and expenditure. He may also have expected that these themes of threats to political stability would lead his politically aware readers to connect the most relevant message of Book V to those advanced in the previous two books of the Politiques . Oresme's predilection for visual emphasis of the dangers to the health of the body politic conforms to the warnings in Aristotle's text. Yet the unified but varied treatment of the theme in three successive illustrations reveals also the translator's personal preoccupation with these subjects, evident in early writings such as the De moneta . In terms of the metaphor of the pathology of the body politic, the overthrow of a regime corresponds to its death. Charles V and his counsellors could not have remained indifferent to such a dramatic outcome as the one examined in Book V. If some implications of these textual and visual interweavings may have escaped his readers, Oresme's oral explications could have knit together the threads.