Six

Of Masks and Mills:

The Enlightened Doctor and His Frightened Patient

Antonie Luyendjk-Elshout

Fear is the most interesting of the passions.

—TOBIAS SMOLLETT, Ferdinand Count Fathom, 1753, 1:21

Of all the sufferings to which the mind of man is liable in this state of darkness and imperfection, the passion of fear is the severest, excepting the remorse of a guilty conscience, which however has much of fear in it, being not solely a tormenting anguish of reflection on the past, but a direful foreboding of the future.

—JAMES BOSWELL, "On Fear," London Magazine, November 1777

In a letter form Antonio Sanches in 1747 the distinguished Leiden professor Hironymus David Gaub learned that his friend was ill. Sanches complained about his health[1] and described his deplorable disease, which was intensifying, twisting around like a snake, producing terrible symptoms like a pudor vitiosum —a consuming timidity—which curtailed his activities as a court physician in Moscow. Gaub was already aware of Sanches's disease. In a previous letter, written in December 1746, he had advised Sanches to try Peruvian bark, which Gaub, among others, considered to be salutary in nervous diseases. Sanches, however, had tried the bark in vain, and Gaub thought it better for him to leave Moscow and find refuge in a warmer, drier climate. "I am afraid," Gaub wrote, "that the loneliness you are enforced to endure will increase this symp-

[1] Letter from Sanches to Gaub, without exact date but probably written in 1747. See S. W. Hamers-van Duynen, Hieronymus David Gaubius (1705 -1780): Zijn correspondentie met Antonio Nunes Ribeiro Sanches en andere tijdgenoten (Assen and Amsterdam: Van Gorcum, 1978), 84-91. Sanches (1699-1783) was a Portuguese Jew, recommended by his teacher Boerhaave in 1731 to the Empress Anna Ivanovna. For political reasons he was obliged to leave Russia in 1747, since Anne's successor Elisabeth Petrovna suspected him of practicing his Jewish religion secretly. See David Willemse, "Antonio Nunes Ribeiro Sanches, élève de Boerhaave et son importance pour la Russie," Janus, suppl. 6 (1966).

tom and finally it will prevent the daily intercourse with people, even ending into misanthropy. Finally, this illness will destroy the power of the herbs."[2] Loneliness, fear, misanthropy: this was the psychological sequence Gaub suspected, yet fear was a common symptom in patients during the eighteenth century. But for Sanches, fear was a consequence of seeing Russia as a hostile foreign environment, and this uneasy situation left him perpetually anxious and uncertain.

This study explores the various roles played by fear in both the theory and practice of medicine in the eighteenth century. Of particular concern is the presentation of fear by patients to physicians, and the varying interpretations of that fear. I will also review the vast repertoire of serious and experimental therapies employed to cope with fear, the state of the patient's mind and body (considered separately and in union), which few physicians understood.

Not even the medical world could be isolated from the ordinary speculations they had engendered. Preachers and philosophers, painters and actors, physicians and authors: all suffered their own concept of fear and anxiety—and these fears were reflected in their behavior: preacher to congregation, actor to audience, and surely, patient to physician. Frightened people have been variously described in a wide body of eighteenth-century literature. What were people afraid of? Did their fears focus on other things than death, poverty, and war? How did they handle stress and anxiety and how did they express their emotions?

My answers to these questions trace the opinions of young physicians who, even in their earliest dissertations, studied and evaluated anxiety and fear. We shall see how their attention and concern created a revolution in the practice of medicine. These studies have a certain fraîcheur, an open-mindedness not often found in accepted textbooks. Moreover, they lead us directly to the important medical opinions of the time delineating fear, and they both reflect and betray the influence of the school and the philosophy that followed. The essence of fear is not easily captured in a brief confession of patient to doctor, and there were few wealthy enough to spend time and money for in-depth consultation. But a few case histories survive, written in the traditional manner and language, and they are most revealing.

By the early eighteenth century, anxiety and extraordinary fear were among the symptoms of insanity, albeit the presence of anxiety in itself was not sufficient to declare a patient insane. Coupled to the physician's

[2] Hamers-van Duynen, Gaubius, 86. Gaub was attempting to keep the power of the bark from public derogation. Since there were no proven drugs, all forms of placebo needed reinforcement and constant postive feedback.

difficulty in weighing the degree of fear and anxiety is the philosophical (and even semantic) category of madness, a category whose history Michel Foucault brilliantly described almost two decades ago.[3] Foucault's work, as is well known, has been developed and refined by a worldwide flood of publications on the history of lunatic asylums, on the treatment of the insane, and on the biographies of those persons concerned.[4] Thus, my interest concerns not the "grande peur" of madness, as so eloquently described by Foucault, but the fears of ordinary people who suffered from ordinary and common somatic diseases and emotional disturbances, from the perturbationes animi, as they were called in the parlance of the time.

One must recognize that the eighteenth-century physician saw as many anxious patients as the physicians of today. He was trained to listen to their complaints, suggest diet and exercise, and prescribe medicines to calm them down. More often it was the surgeon who dealt with truly scared patients—those who had to undergo amputation or other major surgery. Since possibilities of anesthesia were limited, reactions to pain and panic were mixed, and no clear distinction was made between the variety of sensations in the reports of the operation or in learned treatises on the passions of the mind. We would expect to find important answers to our questions about fear in medical treatises, written by either physicians or surgeons who practiced in densely populated areas and major cities of Europe. Medical practice was more limited in the rural districts, where a local surgeon or apothecary more typically kept an open shop, and patients could come for treatment. The complaints of patients from these rural districts rarely reached a doctor of medicine. Peasants often used drugs prepared in the tradition of folk or domestic medicine; a surgeon was visited only in cases of trauma or, if he practiced obstetrics as well, in cases of problems with a delivery. In the country each surgeon had a self-compiled list of medicines. In the Netherlands, for example, the surgeons were not obliged to follow the pharmacopoeia until 1805.[5] There were some books in the vernacular

[3] Michel Foucauh, Histoire de lafolie a l'âge classique (Paris: Gallimard, 1972).

[4] Small research societies in many countries are active in the history of psychiatry, in part as the consequence of this paradigmatic Foucaldian work. In Belgium and the Netherlands, for example, vast inventories have been made of archives and collections dealing with psychiatric hospitals and lunatic asylums. In Belgium, p. van der Meersch has edited studies on psychiatry, religion, and authority; see Psychiatric, Godsdienst en gezag: De ontstaansgeschiedenis van de psychiatrie in Belgie als paradigrna (Leuven: Amersfoort, 1984).

[5] D.J.B. Ringoir, Plattelandschirurgijns in de 17 e en 18e eeuw (Diss. Amsterdam; Bun-nik, 1977), 101. See also G. B. Risse, R. L. Number, and J. W. Leavitt, Medicine without Doctors (New York, 1977).

during the eighteenth century for rural surgeons, some of these being translated pharmacopoeias, but rather little is known about the solitary frightened patients deep in the country. Especially lacking is an understanding of that fear which stems from isolation—the relationship of personal anxiety to the environment.

If we proceeded in this vein, we should soon find ourselves investigating outbursts of mass hysteria, witchcraft, suicides, and riots. Despite the Enlightenment and the rationality it brought with it, a great part of the European population—the poor in the cities and the peasants in the country—was illiterate and hopelessly attached to medical superstition.[6] An example of fear among peasants was recorded by the members of the Académie de la Rochelle in France. In February 1784, only a few months after Montgolfier's experiment, the townspeople were invited by the Academy to be present at a balloon fair, arranged by the local pharmacist. The balloon went up and stayed aloft for about thirteen minutes. When it came down in the open fields where workers were unaware of the event, it was cut to pieces by farmers, who attacked the balloon with their pitchforks. To assuage panic, the town published a pamphlet to explain that the balloon was an experiment, due to natural causes, and not the work of the devil.[7]

PIETY, PATIENTS, AND PASSIONS OF THE MIND

It was early believed that pathological phenomena, such as a state of anxiety, might be a consequence of sin. Metaphysical causes were considered as well: a punishment by God or retribution of debt, which brought the patient into a situation that he needed the assistance of the Church. These interactions between the physical and the metaphysical, between the mind and the body, belonged foremost to the field of moral theology.[8] Doctors were only permitted to give their opinion on the

[6] An impressive study of this problem can be found in Michael MacDonald, Mystical Bedlam: Madness, Anxiety, and Healing in Seventeenth-Century England (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981).

[7] Jean Torlais, "I'Académie de la Rochelle et la diffusion des sciences au XVIII siècle," Revue des sciences 12 (1959): 111-135.

[8] G. S. Rousseau, "Psychology," in The Ferment of Knowledge: Studies in the Historiography of Eighteenth-Century Science, ed. G. S. Rousseau and Roy Porter (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1980), 175. Rousseau wisely pays attention to religious treatises on the soul by English clergymen, adapted by physicians. The French school of historians (especially Annales and the social historians) has been very active in their search for traces of fear in last wills and prayers; see for instance Jean Delumeau in La pent en occident, XVIe au XVIIIe siècle (Paris, 1978).

temper of the patient; they were not free to venture upon the psychological analysis of his fear.[9] It would be fruitless to search medical treatises for such psychological evaluation. Instead of analysis, doctors were trained to substantiate evidence on the four tempers, the choleric, melancholic, phlegmatic, and sanguine temper, and to respond to the predisposition of patients for emotional reactions such as fear. They explained the physiology and pathophysiology of these emotional reactions, they described various case histories, but they refrained from explaining the "spiritual fears," in terms of guilt and remorse.

The pious had a different attitude in the acceptance of the emotionally disturbed patients, different in that they invoked religious agents as antecedent to physiological causes. They did not neglect anatomy or physiology: they rather blended the two into an original pietistic model.[10] This was especially true in Halle, Germany, where Pietism was the leading religion. Michael Alberti (1682-1757) rejected any materialistic explanation of disease, certainly for disease in which the mind was involved. Alberti was the son of a pietist minister. After studying theology and afterwards medicine, he became a devoted pupil of Georg Ernst Stahl (1659-1734), the leading professor of medicine in Halle. Alberti's Specimen Medicinae Theologicae (1726) was an attack against the Cartesian concepts of Friedrich Hoffmann (1660-1742), who discussed the passions of the mind in his Medicina Rationalis Systematica (1716). In the Netherlands, physicotheology became an important field of interest of enlightened Protestantism. It allowed ratio et experientia as a tool for searching the causes of natural phenomena, for emotional disturbances as well as for other diseases.[11] So it is likely that we find more open discussions of the emotions in medical treatises written in the Netherlands at the time of Herman Boerhaave (1668-1738) and Hieronymus David Gaub (1705-1780). The differences between the Leiden and Halle Schools will be discussed later in this essay.

[9] K. Rothschuh, Konzepte der Medizin in der Vergangenheit und Gegenwart (Stuttgart: Hippokrates Verlag, 1978), 67-70.

[10] Rothschuh, Konzepte. An excellent discussion on the attitude of the patient in pietistic centers in Germany has been given by Johanna Geyer-Kordesch, "Cultural Habits of Illness: The Enlightened and the Pious in Eighteenth-Century Germany," in Patients and Practitioners: Lay Perceptions of Medicine in Pre-industrial Society, ed. Roy Porter (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986), 177-204.

[11] J. Bots, Tussen Descartes en Darwin: Geloof en Natuurweteuschap in de achttiende eeuw in Nederland (Assen and Amsterdam, 1972), especially 49-60; J. van den Berg, "Theologie-beoefening te Franeker en te Leiden in de achttiende eeuw," It Beaken: Tydskrift fan de Fryske Akademy 47 (1965): 181-191.

Fear is one of the most important passions of the mind, as the great novelist quoted in the epigraph intuited at mid-century. These passiones animi were a subject of study for philosophers from Aristotle onward, who reduced all passions to pleasure and pain.[12] The philosophers of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries paid sufficient attention to the emotions and their interaction with the body in order to bring these phenomena into agreement with the new philosophy of René Descartes and the discoveries in anatomy and physiology.[13] This newfound classical series of passions attached to pain and pleasure were ira (wrath), terror (fright), metus (fear), moeror (grief), pudor (timidity), spes (hope), gaudium (joy), and amor (love). These passions, like the group of six non-naturals, were most popular in medical literature and had been described by Galen.[14] The nine passions received more attention in the course of the eighteenth century, especially through the contribution of Arnulfe d'Aumont in the Encydopédie of Diderot on health and hygiene.[15] A well-balanced mind was important, not only for the pious and the patients but also for the politicians, to keep the people peaceful and in a state of mental health. Although medical students were primarily engaged in the physical bodily changes accompanying the passions, they referred to John Locke's An Essay concerning Human Understanding (1690)[16] and to Hume's A Treatise of Human Nature (1739), the chapter " On the Passions," for their philosophical backgrounds and understanding of fear. Neither author believed in an inborn ability to reason but accepted experience by way of the external senses at the main source of knowledge. For Hume (1711-1769), the passions were sense perception intercepted by its idea.[17] Hume considered fear a direct passion, an

[12] L. J. Rather, "Old and New Views of the Emotions and Bodily Changes: Wright and Harvey versus Descartes, James and Cannon," Clio Medica 1 (1965): 1-25.

[13] Ibid. Descartes's Les passions de l'âme was translated into Dutch in 1659 by J. L. Glazemaker.

[14] Air, motion and rest, food and drink, sleep and watch, evacuation and retention, and the passions of the mind. For a contemporary definition see John Harris, Lexicon Technicum, or, An universal English Dictionary of Arts and Sciences: explaining not only the Terms of Art, but the Arts Themselves (London, 1736). He describes them as the Non-Natural Things, or the Non-Natural Causes of Diseases. See n. 15.

[15] William Coleman, "Health and Hygiene in the Encyclopédie: A Medical Doctrine for the Bourgeoisie," Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 29 (1974): 399-421. See also L. J. Rather, "The Six Things Non-Natural: A Note on the Original Fate of a Doctrine and a Phrase," Clio Medica 4 (1968): 337-347.

[16] Sylvana Tomaselli, "Descartes, Locke and the Mind/Body Dualism," History of Science 22 (1984): 185-205.

[17] David Hume, A treatise of human nature, being an attempt to introduce the experimental Method of Reasoning into Moral Subjects, vol. a, Of the Passions (London, 1739).

impression that arises immediately from good or evil, from pain or pleasure.[18] He also attached great value to the power of imagination in this passage from the perception of the virtue or vice to the impression he considered almost identical with the passion. Furthermore, Hume used the term "probability" to change a passion:

Throw in a superior degree of probability to the side of griet, you immediately see that the passion diffuses itself over the composition, and tinctures it into fear. Encrease the probability and by that means the grief, the fear prevails still more and more, till at last it runs insensibly, as the joy continually diminishes, into pure grief.[19]

This combination of passions or transitions from one passion into the other was also considered by some medical students from Edinburgh, as we shall see. Combining passions suggested a way of psychological analysis and psychological treatment. Hume's enthusiasm for natural philosophy drove him far so as to compare the passions with optical phenomena:

Are not these as plain proofs, that the passions of fear and hope are mixtures of grief and joy, as in optics it is a proof, that a colour'd ray of the sun passing thro' a prism, is a composition of two others, when as you diminish or increase the quantity of either, you find it prevail proportionally more or less in the composition? I am sure neither natural or moral philosophy admits of stronger proofs.[20]

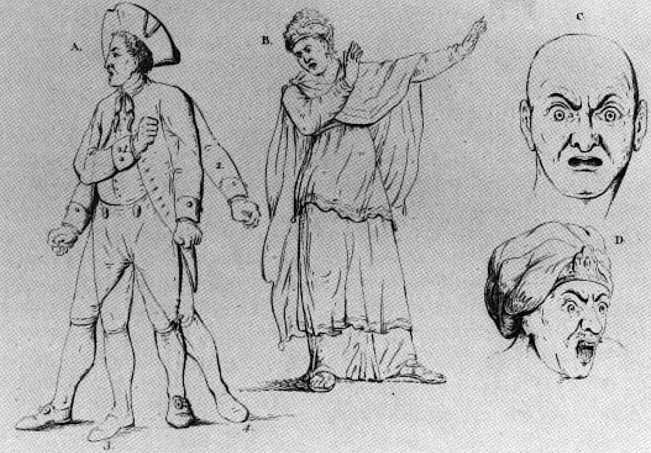

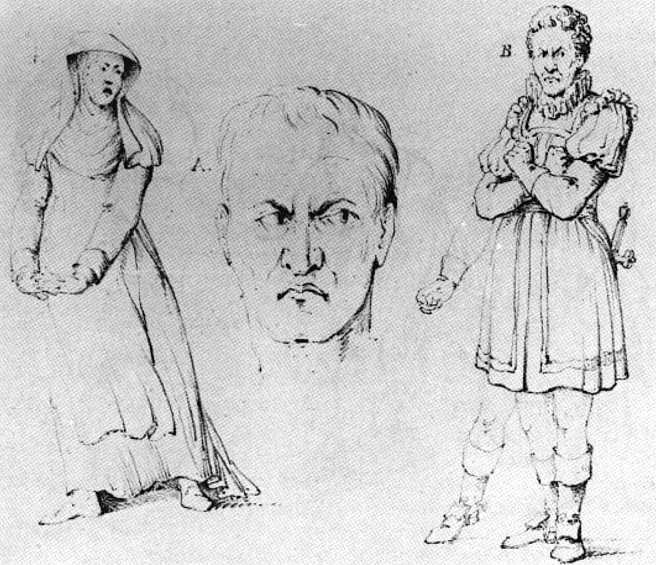

For the enlightened students, educated by ratio et experientia, this metaphor must have been delightful. It is also interesting to notice that ideas of uncertainty in fear are preeminently present in theories of acting. We shall pay brief attention to the concept of fear as it was used in the theater. An actor had to play his part in such a way that his facial expressions and his gestures could be recognized by a large audience. In effect, there were prescriptions for the interpretation of the passions.

A semblance of fear should be expressed by a shrinking of the body; the actor should stand erect, with his arms along his body and his fists closed. His legs should be slightly apart; his eyes should be flickering with a restless glance. He should pace up and down the stage, twisting his fingers, but at the same time keep his shoulders hugged and he should express the uncertainty in his face.[21] These instructions were

[18] Ibid., 181.

[19] Ibid., 218.

[20] Ibid., 219.

[21] J. Jelgershuis, Theoretische lessen over de gesticulatie en mimiek (Amsterdam: Meyer/Warnars, 1827), 150.

Pl. 6. "Expressions of Fear by Actors," in J. Jelgerhuis, Theoretische lessen over gesticulatie en mimiek (Amsterdam, 1827).

partly inspired by the French painter Charles le Brun (1619-1690), who wrote a manual on the way of illustrating the passions.[22] This booklet influenced several Dutch painters including Gerard de Lairesse (1641-1711), who praised le Bruns's work.[23] But the actors were also indebted to Petrus Camper (1722-1789) and Georges Louis Leclerc de Buffon (1708-1788), who paid attention to the physiognomy of the passions from a medical and a biological point of view. Buffon described with great care the changes of the facial expression in various stages of fear, observing the eyes, the eyebrows, the lips, and the opening of the mouth.[24] Petrus Camper tried to explain these changes anatomically, paying tribute to the innervation of the facial muscles and urging his students to notice the changes in the body in general, when they were

[22] Over de afbeelding der Hartstogten of Middelen, om dezelve volkomen te leeren afteekenen, translated into Dutch by F. Kaarsgieter (Amsterdam, 1703), from the original French version by Charles le Brun, Conférence sur l'expression générale et particulière (Paris, 1698).

[23] Jelgershuis, Theoretische lessen, 130.

[24] Buffon's Histoire naturelle was published between 1749 and 1789. Part of this impressive work is on the natural history of man. In this study, he described the expressions of passions. Histoire naturelle, vol. 20 (Paris, 1799), 177, 183).

Pl. 7. "Expressions of Fear by Actors," in J. Jelgerhuis, Theoretische lessen over gesticulatie en mimiek (Amsterdam, 1827).

describing frightened persons.[25] These facial expressions were also observed by the physicians, who mentioned these signs in their description of the frightened patient. But physicians used a medical interpretation; they were more interested in the physiological explanation of the pale color, the trembling lips, and the shaking knees, than in a lively portrayal of the patients' physionomy. We find these representations in particular in some student dissertations.

FEAR AND ANXIETY IN MEDICAL DISEASE

The main diseases of the time which held anxiety as an underlying symptom were hypochondria and hysteria. The diagnosis of such a disease

[25] P. Camper, "Over de wijze, om de onderscheidene hartstogten op onze wezens te verbeelden" (On the way to depict different passions on our appearances). This lecture was presented to the pupils of the Academy of Art in Amsterdam in 1774. Published by A. G. Camper in Redevoeringen van wijlen Petrus Camper (Utrecht, 1792).

was of great importance for a medical practitioner. The treatment would be lengthy and the patient would need serious attention. If he succeeded in curing the patient, he was considered a successful doctor and he could afford himself a praxis aurea, earning much money from usually well-to-do patients. Hypochondria thus became an especially fashionable disease. As the Swiss structuralist critic and historian of medicine Jean Starobinski has pointed out, it was closely related to melancholy, the classic disease described by Hippocrates, as a neuropsychiatric syndrome with depression, hallucinations, mania, and convulsive crises.[26] The theory of the origin of this disease was humoral: a corruption of the black bile would mix with the blood and act as a poison. Afterward, authors differentiated the signs and symptoms of the disease in various clinical pictures. Galen described three types of melancholy, one located in the whole body, one located in the brain, and finally a third type, hypochondriacum flatulentumque morbum , a disease in the upper abdomen with flatulence, belching, abdominal pain, and fear.[27]

This last form of melancholy became a separate entity, known as hypochondria, described in medical treatises from the seventeenth century onward as a common disease. Among others, Robert Burton (1577-1640), who published his Anatomy of Melancholy in 1621, maintained that the boundaries between melancholy and hypochondria stayed rather vague and held that one was simply a form of the other. The physician accepted patients with an isolated delusion as long as they were socially acknowledged as hypochondriacs. He would treat them with much care, provided they were not too excited or aggressive, only involved in their own world, without causing nuisance to their environment. In the event a patient became agitated by a delirium or a dominating "idée fixe," insanity was suggested, and the patient was sent to an asylum for care. Boerhaave took this idle fixe as the most serious symptom of melancholy, combined with the agitated delirium without fever.[28] Hypochondria in the eighteenth century was a disease with a great variety of symptoms

[26] Jean Starobinski, "Geschichte der Melancholiebehandlung yon den Anfäangen bis 1900," Acta Psychosomatica (Basel) 4 (1960): 15.

[27] E. Fischer-Homberger, Hypochondrie, Melancholie bis Neurose: Krankheiten und Zustandsbilder (Bern, Stuttgart, Vienna: Verlag Huber, 1970), 15. The author refers to Galen, De locis affectis, liber 3, cap. 10.

[28] H. Boerhaave, Aphorisms, 1089. The Aphorismi de Cognoscendis et Curandis morbis in usum doctrinae domesticae were first published in Leiden in 1709. They were translated into English by J. de la Coste in 1715 as Boerhaave's Aphorisms concerning the Knowledge and Cure of Diseases.

of which fear was only one of the complaints. It mainly affected men of all ages, and women after their childbearing period.[29] The patients were afraid of death, afraid of diseases, afraid of being poisoned. Sometimes they were possessed by delusions, such as the impression of a number of frogs hidden in their abdomen or that they were changing into glass figures.[30] This glass delusion is a remarkable phenomenon in the history of psychiatry. It was widespread from the beginning of the seventeenth century up to 1850, when the diagnosis disappeared into a new and different system of nosology.[31] Patients suffering a glass or pottery delusion had one thing in common: an obsessive fear they might break into pieces. They did everything to protect themselves; they were even afraid of being pushed or touched.

The first description of such a delusion can be traced back to the second century. It was described by Rufus of Ephesus. The patient fancied himself to be a "keramon," a large piece of pottery.[32] In another case a Florentine nobleman fancied himself to be an oil vessel, and there are various other cases of the pottery delusion to be found in history.[33] In the book On the condition and disposition of the human body, which was published in 1561, the Dutch physician Lieven Lemnius (1505-1568) gave a very exact description of a patient who believed his buttocks to be made of glass.[34] He was afraid to sit down, he thought his buttocks would break and the glass would be scattered all over the floor. This case history was repeated in various textbooks all over Europe. Because of

[29] At the Edinburgh Infirmary thirteen cases of hypochondria, of which nine were men and four women, were registered between 1770 and 1800. G. Risse, Hospital Life in Enlightenment Scotland: Care and Teaching at the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh, Cambridge History of Medicine, ed. Charles Webster and Charles Rosenberg (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986), 153.

[30] F. F. Blok, Caspar Barlaeus: From the correspondence of a melancholic (Assen and Amsterdam: Van Gorcum, 1976), 110. This book deals with the depression of the eminent scholar Caspar Barlaeus (1584-1648), how he informed his friends of the glass delusion and other signs of his disease, and how his friends reacted to his melancholy. It also gives information on the medical treatment of depressions at the time.

[31] A. J. Lameijn, "Wie is van glas? Notities over de geschiedenis van een waan" ("Who is made of glass? Notes on the history of a delusion"), in Een Psychiatrisch Verleden, ed. J. M. W. Binnenveld et al. (Baarn: AMBO, 1982) 26-93. A. J. Lameijn is a Dutch psychiatrist who made a profound study on the glass delusion.

[32] Lameijn, "Wie is van glas?" 28. See also Hellmut Flashar, Melancholic und Melancholiker in den medizinischen Theorieen der Antike (Berlin: de Gruyter, 1966) and Starobinski, "Geschichte der Melancholiebehandlung."

[33] See works cited in n. 32. The case was mentioned by the artist Benvenuto Cellini (1500-1571) in his autobiography, first published in 1728. La Vita was translated into English in 1771 for the first time.

[34] L. Lemnius, De habitu et constitutione corporis (Antwerp, 1561), fol. 141v.

the rather grotesque phenomena of the disease, these delusions became a favorite subject for literature and poetic expression. For instance, Constantijn Huygens, the seminal Dutch poet of the early seventeenth century, wrote a poem as early as 1622 on the glass delusion of a hypochondriac.

Here's one fears everything that moves in his vicinity

What's wrong? Well every where he's touched is made

of glass, you see

The chairs will be the death of him, he trembles at the bed,

Fearful the one will break his bum, the other smash his head

Now it's a kiss appeals him, now a flicked finger shocks

Just as a ship that's gone off course sails, fearful

of the rocks.[35]

The gloomy aspect of these delusions was the loss of the identity of the patient. Moreover, it could mean an impulse for disorderliness, superstition, or even religious sectarianism.

So even in hypochondria or in the twilight zone of melancholy these delusions were observed with suspicion by the enlightened rationalists, since they disturbed the wordly order of state. Henry More warned in his Enthusiasmus Triumphatus (1656) of these perfidious dangers:

For I shall easily further demonstrate that the very nature of Melancholy is such, that it may more fairly and plausibly tempt a man into such conceits of inspiration and supernatural light from God, then it can possibly do into those more extravagant conceits of being Glasse, Butter, a Bird, a Beast, or any such thing.[36]

In contrast, these delusions were mostly accepted as a part of a fashionable, if somewhat seraphic, disease: "the English Malady, the spleen or the Vapours," in Dr. Cheyne's memorable phrase, as hypochondria was known in England and France.[37] The patients were not incarcerated so

[35] Blok, Caspar Barlaeus, 115. Constantijn Huygens (1596-1687) was a well-known poet and secretary to the Stadholder Frederik Hendrik. The poem was probably composed for Barlaeus.

[36] Henry More, Enthusiasmus Triumphatus (London, 1662; reprint, Los Angeles: William Andrews Clark Memorial Library, University of California, 1966, as Publication no. 118 of the Augustan Reprint Society), 10. See also H. J. Schings, Melancholie und Aufklärung (Stuttgart: Metzler Verlag, 1977), for the tensions between delusions and authorities.

[37] Richard Blackmore, A treatise of the Spleen and Vapours (London, 1726), 161-162. See also Ilza Veith, "On Hysterical and Hypochondriacal Afflictions," Bulletin of the History of Medicine 30 (1956): 233-251. There were a vast number of medical treatises written on hypochondria; for a survey of eighteenth-century treatises on this disease see Fischer-Homberger, Hypochondrie, 35-44, also her bibliography.

long as their disease did not develop into the cerebral condition of melancholy, which was considered to be a state of insanity.

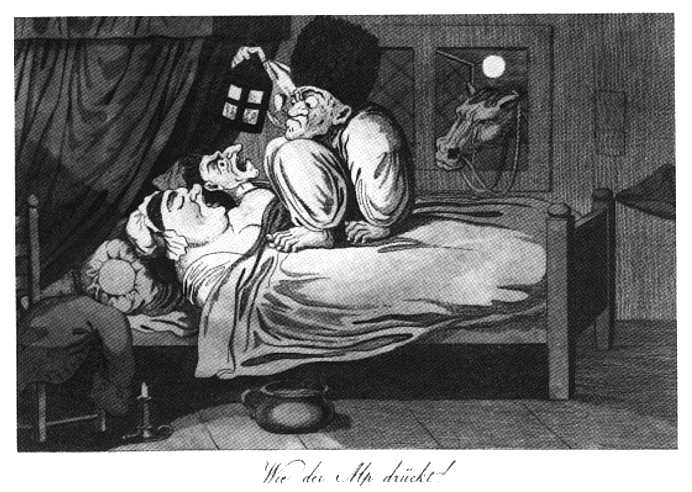

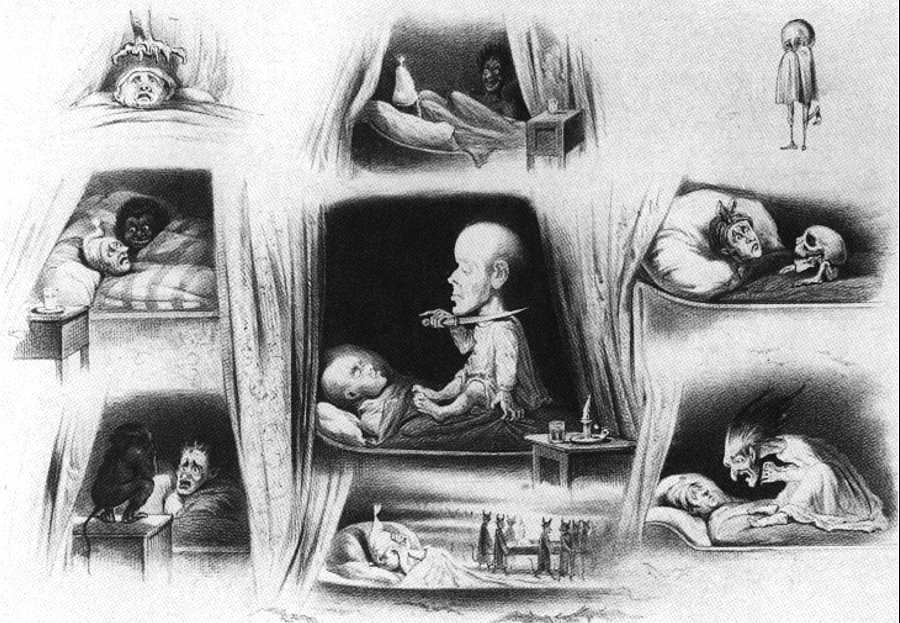

The hypochondriac might also be vexed by the nightly apparition of an incubus.[38] This is a little monster which sits upon the belly of the patient. The poor victim feels a heavy pressure on his stomach, he lies frightened and paralyzed with wide-open eyes looking at his nasty visitor without being able to move or to scream. Sometimes the monster does not sit on his victim, but is experienced as lying under his body. In that case, it is called succubus, a typical nightmare for a male patient, since either the victim or his physician ascribed a sexual origin for the apparition. The students define the succubus as a consequence of onanism,[39] which was coming under the attention of the physicians at the time. When young women complained about suffering from a nightmare in the shape of an incubus, it was usually considered to be a symptom of suppressed sexual desire. Sometimes the victims are caught by seizures, which dispel after some time. This nightmare has a long history. The incubus was already known to St. Augustin[40] and has been associated with demonic powers. When the belief in demons was on the wane, the incubus continued to harass anxious patients. It was used as a theme in art, the good and the bad nightmare, as painted for instance by the Swiss artist Henry Fuseli in 1781.[41]

The presence of an incubus could also be a symptom of hysteria, a condition considered to be the female counterpart of the exclusively male hypochondria. This disease had its seat in the womb. Thomas Sydenham (1624-1689) wrote a famous book on the disease, in which he described the womb as "the seat of a thousand evils," suggesting that Hippocrates had already mentioned this fact. Hysteria caused headache, anxiety, convulsions, and several disturbances in sensation. The greatest

[38] The incubus became a popular theme for medical theses under the influence of the mechanistic explanation of human physiology. In Leiden the first thesis on this subject was defended by a Polish student, Christiaan Maevius, in 1692. In 1734 a Dutch student, Matthaeus Huisinga, presented his Dissertatio Medica Inauguralis sistens Incubi causas praecipuas, followed by the Swedish student Tiberius Zacharias Kiellmann in 1739 on the same subject.

[39] See on this problem Th. Tarczylo, Sexe et liberté au siècle des lurainères (Paris: Presses de la Renaissance, 1983).

[40] Augustinus, De Civitate Dei, liber XV, cap. xxiii. Virgil describes the incubus in the Aeneid, 12.908-912 non lingua valet, non corpore notae sufficient vires; nec vox aut verba sequuntur (the tongue is powerless, the familiar strength fails the body, nor do words or utterance follow—tr. Mackail).

[41] A. M. Hammacher, Phantoms of the Imagination (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1981), 41-46.

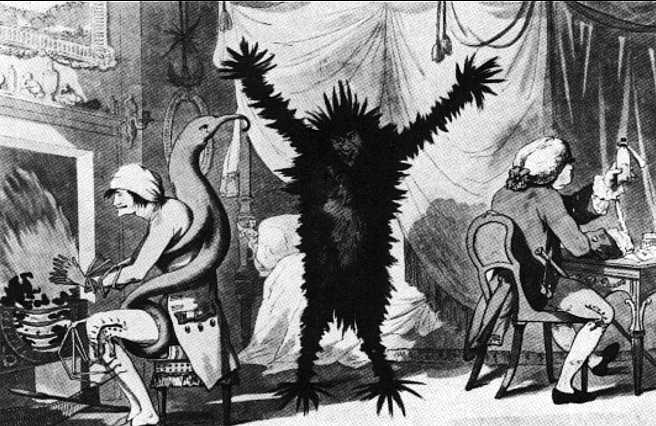

Pl. 8. German cartoon in the manner of Rowlandson, "The Pressure of an Incubus" (ca. 1800).

danger of hysteria was its location; "suffocation of the womb" might affect pregnancy in its early stage and cause serious harm to the embryo. Thomas Sydenham called hysteria and hypochondria the same disease; the hysterical man, however, was only fully accepted in the nineteenth century, when Jean Marie Charcot analyzed hysteria as a neurological disease and traced the signs in both sexes.[42] The frightening symptoms of the disease were usually the changes in body sensations, sometimes followed by convulsions. Gerard van Swieten (1700-1772), professor in Vienna and a true pupil of Boerhaave, ascribed the onset of the disease to emotional breakdown:

Healthy women, who have been made angry or frightened become anxious, their blood gets upset in the vessels and their heartbeats accelerate. Shortly afterwards, they experience something in their abdomen turning and moving, rising on the left side. As soon as this sensation hits the mid-

[42] On hysteria, see Ilza Veith, Hysteria: The History of a Disease (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1965), especially chapters 7 and 8; idem, "On Hysterical and Hypochondriacal afflictions." Also E. Fischer-Homberger, Krankheit Frau und andere Arbeiten zur Medizingeschichte der Frau (Bern, Stuttgart, Vienna: Hans Huber Verlag, 1979).

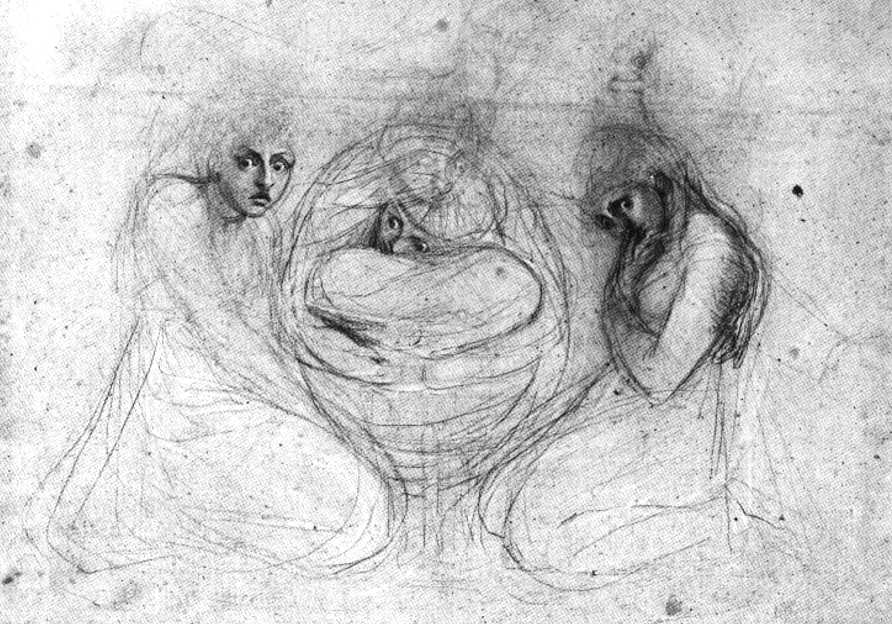

Pl. 9. A. W. M. C. Ver Huell (1822-1897), "Nightmare Showing Incubi," in A. Ver Huell, Zijn er zoo? (Arnhem: P. Gouda Quint, 1852).

Pl. 10. Henry Fuseli, "Three Frightened Girls" (ca. 1780-1782).

riff, they get a feeling as if they are being strangled. Then they experience a heavy globe in their throat, usually they fall into convulsions.[43]

During the eighteenth century the cause of hysteria became firmly rooted in the nervous system. The brain itself was considered to have a high degree of irritability. In addition, patients were believed to have weak cardiovascular and muscular systems: patients fainted easily, even by such light shock as the appearance of a mouse! More serious cases would be accompanied by hysterical paralysis or a disturbed imagination with frightening delusions of devils, making obscene gesticulations. These patients were considered to be possessed by a demon, especially when they had additional symptoms such as a hoarse voice, uttering blasphemy, a tortured face, and a loss of sensibility in certain parts of the body. In these instances the church would be consulted for an exorcism. The more enlightened doctors, however, described these patients as severe cases of hysteria and not victims of the Devil. Anton de Haen (1704-1776), a professor in Vienna and a Dutch pupil of Herman Boerhaave, treated several hysterical patients without the interference of an exorcist with good results.[44] In his book On Miracles de Haen described his rather drastic therapy on severe cases of presumed demoniacal possession. The patient was put under a cold shower each time she started to curse God and the Empress of Austria or other authorities. Certainly these women suffered, but without necessary documentation we lack a full appreciation of eighteenth-century hysteria. More specifically, there seems to have been no instance of a female George Cheyne or John Hill. That is, the expounders of the condition were, like Cheyne and Hill, males, and except for a few comments about hysteria by women (I do not mean in fiction but in didactic-explanatory statements) the medical literature of hysteria is a male record composed exclusively by males. While this archive defines and describes the condition, its degree of sympathy is often lacking, sometimes for no other reason than that the physician could not penetrate its dynamcis. In fact, the cases of

[43] Gerard van Swieten, Commentaria in Hermanni Boerhaave Aphorismos de Cognoscendis et Curandis Morbis (Hildburghausen, 1754), 3:416. Ad S 1075 of Boerhaave's Aphorisms . See n. 28.

[44] See Dieter Cichon, Antonius de Haens Werk "De Magia " (1775), Münstersche Beitrage zur Geschichte und Theorie der Medizin no. 5, ed. K. E. Rothschuh. R. Toellner, and Chr. Probst (Münster, 1971). The medicalization of hysteria was very important, since in Austria witchcraft and incantations still were practiced and consequently witches could be burned at the stake! See also A. De Haen, De Miraculis Liber (Frankfurt and Leipzig, 1776), 194 for his description of a woman, who was supposed to have been possessed by the devil for eighteen years.

the "hysterical passions," as they were called already in 1667 by Willis[45] and others, give us more insight into the phenomenology of hysteria than into the psychology of the suffering women. Furthermore, several of these cases should rightly be considered as the more serious disease, psychosis, a true form of insanity.

Besides the diseases hypochondria and hysteria, or the combined diagnosis, there were various other reasons why patients were continually frightened. As has already been said, we shall not discuss the psychotic fears of the insane patient in this study. Our main interest remains focused on the daily life of men and women who were frightened for some reason and complained about these fears to their family, their friends, or their physician. Such anxieties have been described by scholars in learned treatises and by novelists in literature, but also in a long line of anecdotes, which are repeated again and again from the classical authors like Galen and Pliny onwards. What kinds of fears are mentioned? Besides the fear of the changed bodily sensations in hysteria and hypochondria like the glass delusion, the patients were scared of ghosts, monsters, bed-curtains, mice, earthquakes, explosions, burglars, contagious diseases, and even masks. Both Boerhaave and Tissot believed that masks may be very disconcerting. Tissot referred to Boerhaave in his warnings:

Mr. Boerhaave discussed various cases of epilepsy in his work, following a sudden fright. Two of these cases were caused by masks. If we compare these with my cases we may say that this type of amusement is not without danger.

Indeed, Boerhaave warned against Twelfth Night parties for children and also against "making faces or grimaces." Even the reflecion of a distorted face in a mirror could frighten a sensible person and provoke convulsions.[46] A false face could frighten not only pregnant women and children but even men. We shall return to this point later on.

[45] Thomas Willis accepted already a neurogenic cause of hysteria in 1667. See Veith, Hysteria, 133, 134. See also Robert Frank, chapter 4 above.

[46] S. A. Tissot, Traité des nerfs et leurs maladies (Lausanne, 1778). I consulted part IV from the Œ uvres complètes (Lausanne, 1790). Tissot describes on p. 392 a case of a child frightened by masked children on the street during a party. The child suffered from diarrhea for some weeks. Tissot refers to Boerhaave on p. 406. See Jacobus van Eems, Hermanni Boerhaave Praelectiones Academicae de Morbis Nervorum (Leiden, 1761), 2:801. Boerhaave repeated in his lectures the danger of frightening spectacles and the "homo larvatus," the masked man. See also John Locke, Some Thoughts concerning Education (1693) on scaring children with stories on ghosts and monsters. This work was already translated into Dutch in 1697. A French edition was prepared by P. Coste, which was reprinted many times, the fifth edition in Amsterdam in 1743.

PI. 11. A. W. M. C. Ver Huell (1822-1897), "Fear of the Bed-Curtains," in A. Ver Huell, Zijn er zoo? (Arnhem: P. Gouda Quint, 1852).

But fear and anxiety were most striking in serious affections of the body. It is true, most eighteenth-century studies of anxiety discuss five points of fear accompanying diseases: cardiac origin, an intoxication of the respiratory system, an obstruction of the abdominal tract, different types of fever, and agonia, the struggle with death. Anxiety itself was considered to be of physical origin, while fear was primarily a matter of the mind. Great medical thinkers on disease—Morgagni, Hoffmann, Boerhaave, Van Swieten, Gaub—treated all five of these points in their medical manuals with great attention. Yet we must remember that various symptoms in hypochondria may have had their origin in physical causes, which were yet to be perceived and understood: such as abdominal cancer or obstruction of the pathways of the bile by pathological changes in the tissue of the liver (cirrhosis). A defect of the cardiac valves was often diagnosed as hysteria, as were brain tumors and other neurological diseases. Before introducing some independent theories let us first pay attention to changes in the medical schools, where psychological phenomena were incorporated in the teaching program.

PIETISM, MECHANISM, AND THE SENSORIAL POWERS OF THE BRAIN

At mid-century there were three important medical schools in continental Europe whose leaders held competing medical philosophies: the schools of Georg Ernst Stahl (1659—1734) and Friedrich Hoffmann (1660-1742), both in Halle, Germany, and a third school of Herman Boerhaave (1668-1738) in Leiden. In the schools of Hoffmann and Boerhaave, medicine was practiced on the basis of a mechanical model of the human body. Stahl's system, however, has been labeled animistic or vitalistic. In Stahl's concept the soul is the leading power of the organic structure and is directly involved in any behavior of the body.[47] The impact of these schools upon existing medical education fostered order and structure in the teaching program and generated a rational basis for medicine. In the other European countries there was little impact for a complex number of reasons, much too complicated to be

[47] On the animistic and vitalistic doctrines of Stahl see L. J. Rather, "G. E. Stahl's Psychological Physiology," Bulletin of the History of Medicine 35 (1961: 37-49 and Lester S. King, The Philosophy of Medicine: The Early Eighteenth Century (Cambridge, Mass., and London: Harvard University Press, 1978), 143-151. See also G. S. Rousseau's important study of Enlightenment vitalism and Bakhtin in The Crisis of Modernism: Bergson and the Vitalist Tradition, ed. Frederick Burwick and Paul Douglas (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991).

treated at any length here. In France, mechanism as a leading principle was hardly accepted.

In Germany and Leiden the concepts of the mechanistic schools interacted quite peacefully with the animism of Stahl, especially on physiological grounds such as the circulation of the blood, and the idea of sanitas (health) as an equal, moderate, and continuous perfusion of the humors through the parts of the body. But there was a difference in therapy: Stahl paid more attention to uncommon drugs, which he used in a sophisticated therapy of the presumed cacochymia in the body. Cacochymia was a supposed putrefaction of the body fluids, and an important part of Stahl's concept of disease. The main part of the recommended drugs were herbal, mentioned in the Wurtemberg Pharmacopoeia (1741).[48] Stahl also accepted more uncommon drugs as lapis manati and cornu cervi. Lapis manati is a part of an otic bone of Manatus Australis (sea cow) and was used in treating spasmodic diseases. Cornu cervi (Harts horn), discussed by Stahl in 1690, was a popular antispasmodic remedy in the chemiatric schools. Hoffmann prescribed alterantia to change the temper of the blood and the organs.[49] These medicines were based on the corpuscular theories of Robert Boyle's chemistry, related to the Cartesian concept of the crucial ether as a spiritual fluid through the nerves. Boerhaave wanted to act upon the "spissity" (thickness) of the body fluids and to control the density and the laxity of the fibers. His drugs were mainly Galenic and he attached much value to diet and exercise, especially in cases involving the sufferings and passions of frightened patients.[50]

The extraordinary convergence of Pietism in Halle and a concept of the persona (the soul inextricably linked with man's individual being) created a new school of medicine which the Germans called "Pastoralmedizin," pastoral medicine.[51] In this concept medicine was the servant

[48] See Joachim Petrus Gaetke's dissertation on the general therapy of hypochondriasis, De Vena Portae Porta Malorum Hypochondriaco-splenetico-suffocativo-hysterico-colico-haemorrhoidariorum (Halle, 1698), 52-55 (on the portal vein as the gateway to the evils of hypochondria, of smothering of the spleen and the womb, and of hemorrhoids in the colon).

[49] On Hoffmann's therapy, see K. E. Rotschuh, Konzepte der Medizin in Vergangenheit und Gegenwart (Stuttgart: Hippokrates Verlag, 1978), 247-249.

[50] On Boerhaave's therapy, see B. P. M. Schulte, Hermanni Boerhaave Praelectiones de Morbis Nervorum 1730-1735, Analecta Boerhaaviana, 2, (Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1959).

[51] Wolfram Kaiser and Arina Volker, "Michael Alberti (1682-1757)," Wissenschaftliche Beiträge der Martin-Luther-Universit t (Halle-Wittenberg) 4 (1982): 9-11. See also Rothschuh, Konzepte, 67-70. Michael Alberti was the author of the Specimen Medicinae Theologicae (1726).

of faith and godliness. The conscientia medica, medical conscience, should always be aware of the agreement of a medical theory with theology. Students of pastoral medicine were to learn how to preserve the tranquilliras animi —the mental balance of the patient—a medical approach highly appreciated by evangelists and preachers. Stahl taught that there must be a direct interaction between mind and body and dictated his ideas to his students in the form of deontology: a list of duties including "musts" and "must nots." After digesting this material, students were required to dispute or defend it in dissertation.[52] There are a large number of propemtica (introductions) by Stahl which accompany these student works. In these speeches Stahl emphasizes medical ethics; he discusses the role of the physician in medical practice and his responsibility to his patients. For instance, in 1706 when Henricus König presented a thesis De curatione aequivoca (On a well-balanced therapy), Stahl gave his propemticon De temeritate, timiditate, modestia et moderatione medici (On drastic and reticent, on modest and restrained medical behavior) as an example of variability in an administration of therapy by the physician. Various propemtica such as De Dissensu Medicorum (1703) (On the disagreeing doctors), De Visitatione Aegrorum (1703) (On the visit of patients), De Testimoniis Medici (1706) (On medical reports), De Constantia Medica (1707) (On medical steadfastness), De Auctoritate et Veritate Medica (1705) (On medical authority and integrity) deal with ethics. Hoffmann went even further and expressed the need for morality in some letters to young doctors. One such letter is on physical pietas, which he describes as a spiritual combination of mental and physical health. Thus mental health is only possible as the individual's complete union with, and devotion to, the source of life: God.[53] As such, it may restore physical health in a patient. Stahl stressed this point too in every discussion of the animi pathemata : frightened patients might be bled to restore the temperies of the blood, but Stahl warned his students that if they wanted to treat

[52] A collection of medical dissertations presented to the Halle Faculty is present in the university library a Leiden, dating from 1696-1714. They have been bound in four volumes under the title G. E. Stahl ii... Dissertationes Medicae, turn epistolares turn academicae in unum voluraen congestae (Halle, 1707 ff. ). This collection also contains dissertations defended under the supervision of Hoffmann, A. O. Goelicke (1671-1744) at Magdenburg, Johann Gottfried Berger (1659-1756) at Wittenberg, and Michael Alberti (1682-1757), just mentioned. The volumes of the collection were more or less haphazardly gathered; there is no introduction and the pages are not indicated, except for the first volume.

[53] "Epistola gratularia ad Virum Magnificum, Excellentissimum atque Experientissimum Dn. Bernhardum Barnstorffium," Halle, 1 October 1696, in Stahl, Dissertationes, vol. 3. A congratulatory letter was reserved for important inaugurations "more majorum." In this case, it was Bernard Barnstorff, who was Dean of the Rostock University.

patients psychologically, they should be in tune with themselves and tread lightly,[54] rather resorting to doctrina moralis.[55] Needless to say, students were not permitted to vent their personal opinions in these dissertations, but their experience allowed some conjecture to avoid explanations of diseases by natural or materialistic causes alone.

The state of medical affairs differed profoundly in Leiden. There, students were free to speculate in their writing, albeit more or less in agreement with the current school philosophy. Calvinism and the hierarchical, mechanistic concept of the body guided by an immortal soul were compatible views on man. In Leiden the concept of medicine remained theoretical and scientific; unlike the students in the Halle school, they paid less attention to moral or spiritual issues, to the physician's duties, or to the noble task (officium nobile ) of the physician.

At least in part, the difference in medical thinking was due to the introduction of the concepts irritability and sensibility.[56] The growing importance of the nervous system in physiology focused the attention of scholars on these phenomena. The human body summoned a new view. It became an organism with a mind, which was believed to be responsive to outside influences apart from the pathways of mechanical connections. The mind/body relation became crucial in a different way, as well; more attention was suddenly paid to psychology, education, physiognomy, and medical anthropology. In Leiden, Hieronymus Gaub took the chair after Boerhaave's death in 1738. Gaub's concept of the human body was mechanistic in Boerhaave's sense, but he was also deeply involved in the mind/body discussions then taking place within and without the university, and, especially, in the pathemata of the mind,[57] which

[54] J. J. Reich, "De Passionibus Animi Corpus Humanum Varie Aherantibus" (Diss. Halle, 1695), in Stahl, Dissertationes 1:97. Temperies, "inter se mutua proportia," is meant by Stahl as a chemical balance in the blood; homeostasis in present medicine.

[55] Geyer-Kordesch, "Cultural Habits of Illness" (n. 10 above), 178-204. She considers Pietism an affair of the sentiments. The faithful "feel" themselves pietists. They "feel" God within their heart. (In Calvinism, God is outside, he is the Arbiter, a dialogue is possible.)

[56] Richard Toellner, "Albrecht yon Hailer: Ueber die Einheit im Denken des letzten Universalgelehrten," Sudhoffs Archiv 10 (1972): 17l-182. Albrecht von Hailer published in 1750 his famous study on these properties of the parts of the body, especially of the muscles. Since tissue could react to a stimulus, even when it was no longer in contact with the body, irritability and sensibility had a rather autonomous quality.

[57] L. J. Rather, Mind and Body in Eighteenth-Century Medicine (London: Wellcome Historical Medical Library, 1965). This is an excellent study on Gaub's addresses De Regimine Mentis, quod Medicorum est —a great help for any scholar who wants to be informed on the complex material of the mind/body problem in medicine at the time.

became his preeminent study. He inspired Robert Whytt (1714-1766), the Scots Professor of Medicine in Edinburgh, who used Gaub's textbook for teaching purposes.[58] So there became a close teaching connection between Leiden and the Edinburgh school, founded in 1727 on Boerhaave's model, where the interest in psychological phenomena was growing. We may naturally expect to find concepts derived from both schools in Leiden publications, especially in the students' dissertations.

The growing interest in the sensorial powers of the brain was also responsible for a shift in the concept of disease accompanied by fear such as hypochondria and hysteria, and was especially apparent in the work of Robert Whytt, who declared these diseases to be neurogenic,[59] by which he meant originating in the nervous system. Another important consequence was the popularization of the mind/body subject. S. A. Tissot's (1728-1797) influential book Traité des nerfs et leurs maladies (Lausanne, 1778) became especially popular, not least because he gave an extensive survey of case histories on the animi pathemata, which were cited by professors of medicine all over Europe. The medical schools at Paris and Montpellier, where mechanistic doctrines never took root, explained virtually all emotional disturbances as "crises nerveuses" and looked for chemical changes in the blood and for indigestion.[60] Furthermore, the concept of sympathy gained ground again, especially in Montpellier. This "action on a distance," or external aspects of nerve endings acting in a type of vibrational or materialistic sympathy, was entirely condemned by the mechanists, but later in the eighteenth century it captured the interest of all the European physicians. Tissot paid great attention to the action on a distance upon several parts of the body by the distribution of the peripheral nerve. By this distant influence the brain had the sympathy of the stomach (consensus ), and the concept became very important in physiology and psychology, not only in

[58] R. K. French, Robert Whytt, the Soul, and Medicine, Publications of the Wellcome Institute of the History of Medicine, n.s., vol. 17 (London, 1969), 151. The textbook is H. D. Gaub, Institutiones Pathologiae Medicinalis (Leiden, 1758), which was quite popular. It was translated into English in 1778 by C. Erskine and published by C. Elliot and T. Cadell in London and Edinburgh.

[59] French, Robert Whytt, 31-45. See also Fischer-Homberger, Hypochondrie, 32.

[60] Jean Astruc (1684-1766) lectured in 1759 at the Collège Royal. In this lecture, he discussed the causes of hypochondria and hysteria, especially the primary cause of tension of the nerves. See the MS at the Municipal Archives in Middelburg, corr. David Henri Gallandat (1732-1782). On Gallandat, see G. A. Lindeboom, Dutch Medical Biography: A Biographical Dictionary of Dutch Physicians and Surgeons 1475-1975 (Amsterdam, 1984).

France,[61] where Tissot's influence was considerable, but also in Scotland among Whytt's students.

The consequences for psychotherapy were not obvious. Galenic drugs were still dominant, and as we have seen, Gaub prescribed Peruvian bark and musk for attacks of hysteria or fearfulness.[62] Gaub had a special preparation for his tranquilizing medicine: he combined valerian root with Peruvian bark in a single pill. For hysterical patients his formula was an odorous drink composed of musk, Peruvian bark, and several other herbs. All these herbal and chemical formulas were fine, but they only worked to subdue the hypochondriac's fear. Amelioration required psychological treatment, a subject about which even the young medical students then had suggestions.

PORRIDGE AND RUSSIAN TEA

The following views of the concept "fear" were presented by medical students in their dissertations. Principally, there were three different conceptions: anxiety (anxietas ) fear (metus ), and fright (terror ) The students wrote their treatises in obedience to the philosophical doctrines of the school, but they were encouraged to voice their own opinions; in fact they betray their training ground in a most amusing series of manners. The German students, for instance, were systematic in their discussion of the signs of fear in a patient. They often quote the case histories described by J. N. Pechlin (1644-1692), professor at the University of Kiel in Germany,[63] preferring the tale of the intimidated professor who was so frightened of his students that he would empty his bladder and rectum in a special pot just before he entered the lecture hall. In another

[61] Heini Walther Bucher, Tissot und sein Traité des nerfs: Ein Beitrag zur Medizingeschichte der schweizerischen Aufklärung, Zürcher medizingeschichtliche Abhandlungen, ed. E. H. Ackerknecht, Neue Reihe, 1 (Zurich, 1958), 44-54. For Whytt's relation to the consensus, see the lectured notes of his Edinburgh pupils.

[62] See Hamers-van Duynen, Gaubius (n. 1 above), 186.

[63] J. N. Pechlin, Observationum Physico-Medicarum Libri tres quibua accessit Ephemeris Vulneris Thoracici et in earn Commentarius (Observations in physics and medicine in three books, and a comment on the description of a wound in the chest) (Hamburg, 1691), liber III—obs. XVII: "A Metu alvi flexus" (Loss of Faeces, caused by Fear); mentioned by J. J. Monjé, a student from Tübingen who took his degree in Leiden in 1785: Spec. Medica Inauguralis de animi pathematibus eorum effectibus nec non salutari eorundem in morbis efficacia (Dissertation on the affliction of the soul and their effects, with (sometimes) salutary efficacy in diseases). See also Abraham Heemskerk, Dissertatio ethico-medica inauguralis De Animae Pathemature Efficacia in corpus Humanum (Medical-ethical dissertation on the efficacy of the affliction of the soul upon the human body) (Leiden, 1754). Pechlin is often cited by Gaub in his De Regiraine Mentis etc.

tale, a preacher lost his urine, when he stood in the pulpit preaching about the miracles by Christi A Leiden student tells a similar story, this time about a lady who lost her urine each time she went to Holy Communion. Most of the case histories relating to fear involve rather grotesque details verging on the scatological, and they were repeated in medical textbooks and popular handbooks all over Europe during the late eighteenth century.[64]

Among these dissertations the one written by William Clark, an Englishman, stands out.[65] Clark was a devout Christian who eventually settled down as a general practitioner in rural Wiltshire. In his attempt to reconcile observations in medicine with the Christian faith, his dissertation remains more in the tradition of moral theology than a medical argument. Clark first treats the free will of man, which should, he believes, control the emotions. God gave emotions to man as guardians against evil and danger, and should be compared, by analogy, with physical pain as a bodyguard, which alerts the mind in case the body is threatened. But, Clark contends, the physician's duty extends beyond consideration of the patient's temper. Clark's teacher, Boerhaave, had discussed the observations of Sanctorius (1562-1636) in his lecture on imperceptible perspiration.[66] Sanctorius described this imperceptible natural perspiration under different circumstances. He observed that people who were depressed and scared gained weight; they were "heavier" than when they were happy and relaxed. Boerhaave, said Clark, advised his students to restore the perspiration in case of depressed and frightened patients by administering drugs to open the pores, but Clark disagreed. In his opinion, excitement, caused either by fear or anger, should be tempered, not medicated. To be an Englishman meant to be moderate, and moderation was a way to prevent monumental changes in the quality of the body fluids. The best prevention against

[64] For instance, Wilhelm Gesenius, Medicinisch-moralische Pathematologie oder Versuch über die Leidenschaften und ihren Einfluss auf die Geschäfte des körperlichen Lebens (Erfurt, 1786). The most popular medical book at the time remained S. A. Tissot's Traié des nerfs et leurs maladies (Lausanne, 1790); see n. 46.

[65] Wiliam Clark (1698-1780) studied medicine under Boerhaave and took his medical degree in Leiden in 1727, writing a dissertation on the influences of the emotions upon the human body (Dissertatio Medica Inauguralis De Viribus Animi Pathematum in corpus humanum ).

[66] Sanctorius published in 1614 his Ars de Statica Medicina aphorismorum sectionibus septan comprehensa (Treatise on static medicine contained in seven sections of aphorisms) in Venice. He became one of the founders of the Italian iatromechanical school. The Leiden edition of Medicina Statica was published in 1728. Clark refers to Boerhaave's lectures after hearing Boerhaave speak on the insensible perspiration in case of emotions.

these ominous changes (which might provoke water retention) was daily consumption of a rich, English porridge, and a flask of Rhine-wine at night. Thereby Clark drew attention to the relaxing effect of food and drink in a tense patient.

Clark also bore great admiration for the well-known doctor George Cheyne, whose treatise entitled An Essay on Health and Long Life was published in 1726.[67] The last paragraph of Clark's dissertation is a long and reverent quotation from a chapter by Dr. Cheyne on the affectus animi.[68] Clark's theory of fear may be medical and derived from Boerhaave's lectures, but his main concept lies more in the tradition of moral theology than in moral treatment. His ideology is more involved in faith than in medicine. He accepts Boerhaave's explanation of the physiological phenomenon of fear according to the experiments of Sanctorius, but he objects as follows:

What is said in Sanctorius' theory on the effect of expected joy and hope, could more justly be applied to the hope and faith of the Christian believers.[69]

It is the charitas divina that gives these laws to the animi pathemata. Man should listen first to God (Paul,Rom. 2:15): one knows best in his heart. Clark considers disease to be a punishment of God, also a fear. He is aware of physiology and his medicines are meant to calm down an upset stomach, but he resists interfering in the pattern of anxiety by introducing psychological factors or attempting to analyze the patient's fear.

Clark's dissertation on fear differed considerably from one presented in 1738 by another student of Boerhaave, Otto Barckhuysen, a Russian student in Leiden about whom virtually nothing biographical is known.[70] Barckhuysen discussed his idea of terror as a sudden, unexpected confrontation with a danger, which resembles our notion of fright or alarm. But he was not inclined to call upon the metaphysical, and was interested neither in the seat of the soul nor in the interaction between body and soul and its relation to God. Barckhuysen also rejected Leibniz's theory

[67] In London, 1726, by Strahan, and in Bath by John Leake.

[68] He refers to G. Cheyne, Tractatus de Sanitate Tuenda, cap. de animi affectis, sec. 22. See on Dr. Cheyne: G. S. Rousseau, "Medicine and Millenarianism: 'Immortal Dr. Cheyne," in Hermeticisra in the Renaissance: Studies in Honor of Dame Frances Yates, ed. Allen Debus and Ingrid Merkel (Cranbury, N.J.: Associated University Press, 1987), 192-230.

[69] Clark, Dissertatio, 25.

[70] Otto Barckhuysen, Diss. med. inaug, sistens considerationem Terroris Pathologico-Therapeuticam (Medical dissertation for the doctor's degree, on the pathology and therapy of terror) (Leiden, 1738).

Pl. 12. Cartoon by T. Rowlandson, "Delirium with Fever" (1792).

of a preestablished harmony, which means that he rejected the notion of a perfect dock-like arrangement between body and soul.[71]

Barckhuysen argued that physicians should be direct and practical, should observe the psychological reactions of their patients, and should try to understand the principles of these reactions. Neither philosophers nor moralists should interfere with the treatment of the fearful patient. Barckhuysen provides the example of a merchant who hears the news of a shipwrecking of one of his best ships loaded with merchandise, which partly belonged to some merchant colleagues under his charge. He reasons that the best way to break the catastrophic news to this poor man is to inform him gradually —this pace is crucial. If the merchant were to be confronted with the full reality at once, he may become morbidly terrified, which can lead in turn to apoplexia or even to sudden death. By contrast, when he is intentionally kept in suspense, merely

[71] At the time a dispute raged between Stahl and Leibniz on the agreement. See L. J. Rather and J. B. Frerichs, "The Leibniz-Stahl Controversy—I, Leibniz' Opening Objections to the Theoria Medica Vera, " Clio Medica 3 (1968): 21-40; "II, Stahi's Survey of the Principal Points of Doubt," Clio Medica 5 (1979): 53-67· Leibniz compares the action of the body and that of the soul as the maintenance of a perfect synchronization of two independent clocks.

supposing the ship is missing but having no further news, he naturally becomes a victim of anxiety, which may cause loss of body temperature and perspiration, as described above, accompanied by palpitation of the heart, paleness, and shivering. Slowly induced anxiety is preferable to shock, says Barckhuysen, since the body can then build up a kind of physical resistance to the full impact of the catastrophe. In the meantime the doctors can take care of his comfort. As an ameliorative he suggests some hot Russian tea, carefully prepared from several mixed herbs! Barckhuysen is very proud of his Russian compatriots. Generally speaking, he says, the Russians are not easily frightened; they harden their bodies and minds by swimming in an air hole in the ice, even during the severest cold of wintertime.

Clark and Barckhuysen, both true followers of Boerhaave's doctrines, did not try to analyze the psychological factors involved in the process of fear. They did not define guilt or hallucination, nor did they refine the differences between anxiety and oppression. Mainly, they interpreted all ailments of the psyche as a breakdown of mental processes which allowed for depression and the symptoms of fear and anxiety to surface in response to stress. Moreover, anxiety and fear were used as synonyms for the same state of mind, albeit that most students attributed a corporeal quality to anxiety and a spiritual quality to fear. The difference m the treatises that have anxiety as a subject and those that deal with one or more emotions (animi pathemata ) lies in the choice of the diseases put forward in the dissertations. For example, anxiety and pain are closely intermingled in the diseases discussed by those students who took anxietas as a subject of their studies. Five corporeal examples of anxiety are prominent in these studies: anxiety caused by (1) heart failure, by (2) pulmonary obstruction, by (3) abdominal oppression, by (4) serious affects of the nervous system, and by (5) surgical intervention.[72]

By discussing these five examples of anxiety, the students could test their knowledge of clinical medicine, culminating in a long description of agonia, the struggle with death.[73] Moreover, they could demonstrate

[72] See Francis Gallis, Disputatio Medica lnauguralis de Anxietate (Harderwijk, 1739): he followed Boerhaave's institutions, but his therapy is based on Stahl's doctrines. Dirk Schouten, Disputatio Medica Inauguralis de Anxietate (Leiden, 1742): Boerhaavian physiology, Hoffmann's therapy. Isaac Voyer, Dissertatio Medica Inauguralis de Anxietate (Leiden, 1769): following Hieronymus David Gaub, Institutiones Pathologiae medicinalis (Leiden, 1758), S 683.

[73] Prosper Alpinus, De Praesagienda Vita et Morte Aegrotantium Libri Septem, ed. H. Boerhaave, emendationes Hier. Day. Gaubius (Leiden: Ex. off. Isaaci Severini, 1733; editio princeps, Frankfurt, 1601). Boerhaave considered this work of the highest importance for the daily praxis of medicine. Prosper Alpinus was a famous physician who became director of the botanical garden at the University of Padua in 1593.

that they had followed Boerhaave's clinical teaching in the Caecilia hospital as well as his instruction in physiology. With the help of his pupil H. D. Gaub, Boerhaave edited The prediction of life and death of the diseased (1733) by the famous Italian physician Prosper Alpinus (1533-1617). The definition of anxiety in this context is: the sad and obstructed perception of the mind or the sensation that our life is fading away.[74] For instance, this feeling of terror is dominant in being choked, in having a perforated stomach, or in the terrible anxiety in rabies. The more subtle feelings of anxiety as experienced in hypochondria or hysteria were of relatively minor concern to these students, whose interest was peaked by more serious diseases. They were most eager to explain these dreadful sensations in terms of iatromechanics. The affliction of the mind was considered to be only a consequence of the disease itself; it was a consensus (sympathy) between the brain and the affected organs. This thinking is evident in the medical explanation of the incubus;[75] such a monster does not really exist. It is a product of imagination, caused by oppression of the abdominal area, due to overeating and drinking too much wine. It is a consequence of Newton's laws of gravity, which teach us that the weight of a body presses against another body with a certain force. Thus, the stomach presses against the diaphragm and the diaphragm presses against the heart. By this pressure the circulation to the head becomes obstructed, and the ventricles of the brain become overfilled, the pressure disturbs the animal spirits, and the monster appears in a certain shape to the patient, such as his imagination would allow.

These strict mechanical explanations are also applied to the serious conditions of heart failure, gas poisoning with sulphureous vapors in volcanic eruptions, and the frightening experience of the amputation of a leg. Medical students paid little mind to the workings of the imagination; we must look instead for studies on the affectus animi, or on the

[74] "Anxietas est ergo illa tristis, molestaque Mentis perceptio, vel sensus quo putamus vitam destituram esse." See also Schouten, De Anxietate, and Gallis, De Anxietate, who claim that it is "quasi certamen cum morte" (any anxiety is like a struggle with death). The word agonia (Greek) was used in ancient medicine, similar to angor in the double meaning of combat and anxiety. See Prosper Alpinus, De Praesagienda Vita, lib. III, cap. IV.

[75] See Huisinga, Dissertatio... sistens Incubi causas praecipuas (n. 38 above). He gives a mechanical explanation. The backward position of the head gives an intracranial obstruction of the ventricles, there is no more secretion of the animal spirits, so the body cannot move. The apparition of the incubus is not a matter of metaphysics but a product of imagination.

perturbationes animi —in other words: on the effects of the emotions upon the mind.

MUSIC AND NO-RESTRAINT

In 1735 we find the very first testimony in the Leiden school of a changing interest in the animi pathemata. James Goddard, a student from Jamaica, defends under Boerhaave his dissertation De animi Perturbationibus (On the disturbances of the mind),[76] in which the beginnings of psychology are discernible. Goddard, already recognized for his work on Descartes, Hobbes, and Locke,[77] was impressed by the series of lectures on diseases of the nervous system presented by Boerhaave between 1730 and 1735. In these lectures Boerhaave gave several explanations of the transmission of emotional disturbances to the different parts of the body. Goddard grew interested in this theme and expanded it, describing several symptoms of body change as a consequence of hidden fear: the voice of the patient changes, it is softer, the stomach suffers from spasm, the pulse becomes smaller and accelerates. He also notes changes in facial expression, the paleness, the restless glance. Goddard provides an amusing picture of anthropological and environmental differences between people with regard to their emotional reactions: Catalans are restrained and do not show their emotions, the French on the contrary are more exuberant. People from the mountains and people living in the plains react differently, as Hippocrates taught. Goddard then deals with inherited traits. An aggressive father will beget a hot-tempered lad, and a funk (stercoraeus) will beget a funk! He believes that passions have a contagious affect: "like laughing faces get moist when crying people come in," or "like a disease strikes as lightning, a sudden emotion can spread easily." According to Goddard, women are

[76] James Goddard was born in 1714 in St. Ann, Jamaica. In 1732 he attended Jesus College, Oxford; in 1733 he matriculated in Leiden. Boerhaave took personal care of this dissertation. R. W. Innes Smith, English-speaking Students at the University of Leiden (Edinburgh and London, 1932).

[77] John Locke's Some Thoughts concerning Education (1693) was translated into Dutch in 1698 by Barent Bos in Rotterdam under the title Verhandeling over de opvoeding der kinderen. Another Dutch edition was published in 1753 in Amsterdam by K. van Tongerlo and F. Houttuyn. Locke's theories on education were discussed in lectures, probably by Gaub. Thomas Hobbes was following Descartes, but his mechanism and materialism were condemned by the authorities of the church as well as by university professors. Goddard rejects Hobbes's theories from De Homine (1657) on the innata praenotio (inborn knowledge).

much more susceptible to fear than men, especially when they eat too many sweets.

He also proposes various therapeutic measures against fear. The majority of these prescriptions were already well known and frequently mentioned by the teachers of the schools in Europe. We can find them in all books on hypochondria, such as George Cheyne's English Malady (1733),[78] q which was most popular during the eighteenth century. Physical exercise, fresh air, moderation in the use of alcohol, and a light diet without herbs or fat food. Especially for fear and sadness Goddard recommends the soothing affects of music and traveling, preferably sea voyages, or occupational therapy. We can recognize those advices as being already familiar in the chapters on hygiene in the ancient textbooks. So far as music therapy was concerned, Goddard referred to the Tusculan Disputations of Cicero[79] and mentioned Pythagoras's therapy with the violin and songs. Music therapy became popular again in the eighteenth century, especially in those systems of medicine which had a mechanical background: Goddard calls it a medicamentum amabile and he points out the use of musical therapy in tarantism, a disease caused by the bite of the tarantula, a spider that was common in harvest time, especially in Italy. He does not discuss the physiology of the cure. Goddard's psychotherapy is partly suggestive; when the physician prescribes remedies, he should emphasize the beneficial effects to be expected from their use. Hope and optimism, bolstered by proper medical guidance, should keep fear at distance. The author does not suggest tranquilizing the patient's mind. Emotions, even fear or grief, are necessary for a healthy life. Life should not be a stagnant pool; the passionless doctrines of any form of Stoicism are unhealthy for the patient.

[78] George Cheyne, The English Malady: or, A Treatise of nervous diseases of all kinds, as spleen, vapours, lowness of spicity, hypochondriacal and hysterical distempers, etc. (London and Dublin, 1733). On Cheyne, see Rousseau, "Medicine and Millenarianism' (n. 68 above). A popular work called Hypochondriasis, a practical treatise on the nature and cure of that disorder, commonly called the hype and the hypo was written in 1766 by John Hill. It was reprinted in 1969 with notes and apparatus by G. S. Rousseau.

[79] Goddard refers to Tusculan Disputations, liber IV, cap. II. In this chapter Cicero points at the importance of the music of the harp as soothing the emotions. See also H. J. Möller, Geschichte und Gegenwart musiktherapeutischerKonzeptionen (Stuttgart: J. Fink Verlag, 1971), 18. Also W. Kümmel, Musik und Medizin: Ihre Wechselbeziehungen in Theorie und Praxis von 800-1800 (Freiburg and Munich, 1977) as a general survey. Also E. Ash-worth Underwood, "Apollo and Terpsichore: Music and the Healing Art," Bulletin of the History of Medicine 21 (1947): 639-673. The general idea in the eighteenth century was that music stimulated the vital spirits by the composition of the sound waves, which penetrated into the brain.

Stoicism, as other authors in this book have noticed in its national contexts, was a dominant philosophy in Leiden during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. The ancient authors like Seneca, Plautus, Tacitus, and Terence were studied, and the virtues of steadfastness, modesty, and prudence were elements of the neo-Stoic moral philosophy.[80] This morality suggested a strong mind, not sensitive to emotions, and a capacity for self-restraint. Goddard is against this hiding, this repression, of emotions. He opts for a no-restraint therapy: let the patient scream it out !