PART II

ECONOMICS

2

Professions and Patronage I: Teaching and Composing

In the absence of settings of the kind that the church, the court, and the state have traditionally provided in Europe, music in the United States has depended chiefly on the success musicians have had in finding customers and serving their needs. As Roger Sessions wrote in 1948, any serious consideration of American musical life must begin with the recognition that music in this country has been and is a "business."[1]

In one sense, Sessions's statement is a truism. Of course music, insofar as it depends upon the marshaling of specialists prepared for difficult tasks, is an expensive pastime, and the money has to come from somewhere. The more we study the past, the harder it is to overlook arrangements that provide for the training of artists and the commissioning, performance, circulation, and preservation of their works. Whether American or European, musicians are no different from other human beings in their need to make a living.

Yet, because Sessions has fashioned his statement to jar musical readers into recognizing an unwelcome fact of life, it's best to view it with that purpose in mind.[2] Two related premises loom behind it. One is that the European scene is different; the other is that Sessions's own kind of music operates at a disadvantage in a business climate. On the first point, Sessions's claim suggests the absence in America of prestigious institutional venues within which the creation and performance of musical works, conceived as art and not business, is encouraged. Readers are reminded that the realm of musical "art," which the American public is encouraged to think of as a wholly idealistic endeavor, is, for those engaged in it, an occupational calling in which musicians exchange their time and skill for money. On the second point, by re-

stricting his discussion to music in the cultivated tradition, Sessions reveals an anomaly: The American music about which he cares the most must make its way in an environment indifferent or even hostile to it.

While Sessions's subject is music for the concert hall and opera house, his article is conceived broadly enough to take in all of American music. Rather than denouncing business, Sessions describes it. The nature of business, he reminds his readers, is to seek the highest possible return on one's investment. To that end, a business tries "to produce its goods as cheaply as possible." It also tries to encourage in customers a demand for products that are "cheapest and most convenient to produce."[3] Thus, cheap production, wide demand, and maximum profit are its prevailing values. Around these values there has been built in the United States a central marketplace—an arena centering on fierce competition for a paying audience. To compete successfully in that marketplace, musicians must follow the practices of an enterprise ruled by business. They must, in other words, produce musical commodities: goods or products suited to marketplace exchange.[4]

It is as obvious today as it was four decades ago that pure business values are foreign to the milieu in which Sessions and his compatriots understand themselves to be working. For there, works of art are privileged in and of themselves, often without reference to their exchange value. As makers of these works, composers stand at the top of a hierarchy: composer, performer, listener. Rather than catering to public taste, they seek to lead it, in the name of ideals they see as traditional and artistic—including "the prestige of sheer quality."[5] In essence, they practice art for art's sake. And they do so by making musical statements that, drawing from the full range of techniques available, seek to reflect the modern world as masterpieces of the past reflected the spirit of theirs. For Sessions, such music offers "new experience"; its makers must not shrink from placing stem demands "upon performers and listeners alike." In "an economy of scarcity," however, such "problematic" contemporary music cannot be expected to flourish.[6]

Sessions's claim that music in America is first and foremost a business makes an excellent jumping-off point for a broader inquiry. It's a strong statement from a respected source. Its application to the whole of American music—some branches of which embrace business values as unreservedly as Sessions and his compatriots reject them—can be an illuminating exercise. For example, cheap production, wide demand, and

maximum profit may promote conformity, but the pursuit of such commercial goals has not cramped the diversity of American musical life. The careers of Sessions and his fellow composers testify to the flexibility possible within the larger economy of American music. The cultivated American composer's direct economic power may be modest. Yet Sessions, his compatriots, and his successors have found a way to live as musicians—to receive training, to find musical employment that involves composing, to work professionally at their calling, and to have their works performed and disseminated (i.e., published, recorded), though perhaps on a scale smaller than they wish. They have found in the larger American music business an arena for their talents and beliefs, even though those have aroused little interest in the central marketplace. They have found an economy within an economy: a realm that has also enabled them to hold to their ideals and to keep alive, in a democracy where commercial values overshadow other values, the spirit of music as an esoteric art.

It's remarkable that American composers have accomplished what they have. Their accomplishment is part of a larger story—one that considers music in the United States as an art that has grown up alongside a highly varied economic system. That system is carried forward by agents who serve the many functions necessary to the practice of music in the modern Western world.[7] All pieces of music must be created in the first place, and musical creation is the province of the composer . Before a composer's music can be experienced, someone must sing or play it, and that's the province of the performer . Composing and performing music take special skills, of course, and formal instruction in those skills is up to the teacher . If music is to find its way from composers to performers and, eventually, to listeners, it must be publicly performed, reproduced and distributed (i.e., published, recorded); those tasks fall to the distributor . As an art of sound, music relies not only on the human voice but upon musical instruments (and, in the electronic age, on mechanical playback equipment), and the manufacturer of such instruments is another agent of the music business. Finally, as an art form concerned with the human condition, music is an object of reflection and contemplation, and interpreting its messages in words is the province of the musical writer .

Each of these agents—composer, performer, teacher, distributor, manufacturer, writer—has played a role in the development of music

in the Western world. Together, their efforts have created the economic structure of music-making. Yet the agents differ among themselves in background, training, and priorities, as a profession differs from a trade, a craft, or a business.[8] Sessions writes with the confidence of a true professional—a practitioner whose occupation is defined not by economic reward but by intellectual autonomy and authority.[9] According to Virgil Thomson, who wrote penetratingly on "the civil status of musicians," what separates a profession from other kinds of occupational calling are three special marks of "professional integrity": (1) "members of the profession are the final judges on any question involving technique"; (2) "professional groups operate their own educational machinery and are the only persons legally competent to attest its results"; and (3) "their professional solidarity is unique and indissoluble." Performers and music business functionaries may be brilliant or powerful or both, but they wield no authority on composers' own turf. "No executant musician," Thomson proclaims, "has the right to perform publicly an altered or reorchestrated version of a piece of music without the composer's consent." He uses an analogy from medicine to dramatize a composer's hegemony in the musical world. If a surgeon, he writes, "prefers to cut out appendices with a sterilized can-opener, no power in western society can prevent him from doing so, excepting the individual patient's refusal to be operated on at all." As for competence to judge the outcome of professional education, Thomson admits that "a certain number of prize competitions [are] still judged by orchestra conductors and concert managers." But still he insists: "Nobody but composers can attest a student's mastery of the classical techniques of musical composition or admit [another composer] to membership in any performing rights society." Finally, Thomson notes that only rarely do professionals "allow controversy to diminish their authority or their receipts." "Every profession administers a body of knowledge that is indispensable to society," he believes, "and it administers that knowledge as a monopoly."[10]

Thomson's view of musicians' occupations is functional and hierarchical. For what, precisely, do different musical agents get paid, he asks? The answers determine their places in a hierarchy that privileges intellectual autonomy and control, with composers at the top.[11] Composers make the designs upon which other agents depend. While they

may work on commission—that is, collect a fee to compose a certain piece—their professional income reflects most of all their success in leasing to others the rights to perform, record, or otherwise "exploit" their music.[12] Performers "execute" the patterns made by composers and, as Thomson says, are "paid by the hour." Their work also demands a high degree of skill, which identifies them occupationally as craft practitioners. (One might add, as Thomson does not, that in vernacular music, having gained the composer's implicit or explicit assent, performers reinterpret and recompose pieces and hence assume some of the composer's function.) Teachers' occupational status is a matter of some dispute. Their calling fits the standard definition of "profession" more closely than the composer's does, for teaching is often a full-time, income-producing occupation, it requires extended practical and theoretical training as well as certification, and it espouses an ethic of service. Yet teaching—more a means to an end than an end in itself— lacks the intellectual autonomy enjoyed by other professions. For now, perhaps it will be enough to classify teaching (and writing about music, too) as part profession and part not, returning for a closer look later in the chapter.[13] As for the other agents of music, distributing music is clearly not a profession, a craft, or a trade but a business, while manufacturing musical instruments and goods involves both craft and business skills.[14]

Music-making in the United States has been shaped by professionals, trade and craft practitioners, and business people who, working alone or together, have followed the occupational callings open to them. What is crucial to note is how differently music has been financed in the United States and western Europe. In Europe, whether or not individual musicians were able to take advantage of it, financial support for artistic activity, in the form of patronage, emanated from the top of a hierarchical society whose ordering was hereditary. In America, where any social hierarchy has been unofficial, temporary, and nonhereditary, musicians have had to find their own support. In the Old World, structures dispensing artistic patronage already existed; music-making was stimulated by and flowed into them. In the New World, such structures, where there were any, were by-products, results and not causes, of musical activity. Music-making in America was able to create such structures of financial support only at points where enough money was

earned or donated to perpetuate some institution with continuity—for example, a publishing firm, a conservatory, a theatrical circuit, or a symphony orchestra.

The story of American musical "economies" is complex. Each profession, craft, trade, or business has its own history, accessible chiefly through biographical study. But while the scholarly literature is rich in biographies of musicians as artists, we know much less about the field's trade practitioners and business leaders. Who were the people who had the most to do with shaping each of the American musical callings, and how do we know? What can we learn about their practice of that calling, especially from an economic point of view? What occupations did musicians pursue in the course of their lives, and how did they pursue them? By studying many individuals, will we find patterns that will lead to a better understanding of their occupations? Once occupational roles are more carefully separated and considered, what can we learn by examining their relatedness, both in the lives of individual musicians and, more generally, in the musical activity of institutions, locales, and the nation as a whole?[15]

An inquiry like the present one can do little more than to raise such questions. Nor would even detailed answers to all of them tell the full story of American musical "economies." Not all support for American music has come from earned income. At certain points in the story, patronage has appeared—patronage in the European sense, where a patron gives money to an artist for the production and/or performance of works of art. Not until well into the nineteenth century did patronage begin to contribute to American structures of musical support—structures that in Europe were traditional. And not until our own century has the state involved itself in musical support in any important way.

This chapter and the next sketch some of the ways in which musical professions and occupations have functioned in American musical life. As the normal agencies for American music-making, musical occupations offer a vantage point that, like the historiographical one of chapter 1, complements the customary view of the history of music, which is centered upon musical compositions, styles, and genres. The professions and occupations have also established the context in which patronage has appeared. As departures from the norm, examples of American musical patronage are best considered unusual events, called into play by extraordinary circumstances.

There's little ambiguity in the openly commercial grounding of many American musical transactions. But as we recoguize "business" as the very turf upon which American musical life has been constituted, we see more clearly that musicians' need to make a living has been the driving force behind two centuries of American music-making. That recognition undermines confidence in a fixed border between "commercial" and "noncommercial" arenas. Moreover, as we come to appreciate the artistry of certain commercially driven American musicians—Irving Berlin is a good recent example—we are reminded that commercial motives do not necessarily overwhelm all others. The artistic legacy of unabashed commercialism may be as mixed as that of other motives that American musicians have espoused. But the reach of commercial values, however ample, has left open spaces in the American musical landscape for other values to appear. Musicians in callings remote from money and the power that it brings have shown great resourcefulness in attaching themselves to American beliefs and values that extend beyond the commercial arena and even beyond music itself. Thus, like Sessions and his compatriots, they have discovered how, within the American music business, to carry on musical activities that cannot pay for themselves.

Let's begin our survey with a statement from 1753 about the post of organist at St. Philip's Anglican Church in Charleston, South Carolina. According to the Vestry, St. Philip's organist could expect to make about £200 per year. Earnings would come from three sources:

1. pay for playing the organ, about £50 yearly, or one-fourth of the total earnings;

2. fees for "teaching the Harpsichord or Spinnet" privately, projected at "at least . . . 100 if not 150 Guineas" per year, which amounts to half, and perhaps as much as three-fourths of the total;

3. fees for performing in public concerts, which might amount to as much as "30 or 40 Guineas per Annum more" per year.

In other words, the holder of what was surely a prestigious musical post in eighteenth-century Charleston could expect to make less than half

his living by fulfilling that post's official duties. Most of his income was to come from giving private lessons—from teaching music rather than playing it. As for concerts, he could expect relatively little from them, and then only if he showed "obliging Behaviour to the Gentlemen and Ladies of the place."[16]

The priorities of this document from the Colonial south reverberate through the later history of American music. Indeed, from the eighteenth century to the present, what Americans have wanted more than anything else from musicians is to be taught to sing and to play. Teaching has been the skill most widely demanded of musicians, the calling most readily available, the American musician's bread and butter, the service musicians have most often exchanged for a chance to pursue the musical passions closest to their hearts. Teaching is thus the logical starting point for our consideration of musical occupations in the United States.

In eighteenth-century America, singing masters who organized singing schools in which beginners were taught to sing sacred music outnumbered private teachers by far. Private teachers (like the Charleston organist) plied their trade chiefly in cities, where affluence and leisure time helped to form a public willing to pay for performance instruction. Singing masters worked both the city and the countryside, offering congregations and choirs in hamlets and villages the chance to improve their sung praise to the Almighty. Private lessons were one-on-one encounters; singing-school classes could reach dozens of scholars at once and cost the scholars only a modest fee.[17] A private teacher was most likely an immigrant and a professional musician, a performer on several instruments who offered other musical services for sale as well.[18] In contrast, singing masters needed to know only the standard psalm tunes and "the gamut"—the system of solmization. They were American-born, musically educated in singing schools themselves, and unlikely to make a whole career of the singing master's trade.[19] The private teacher and the singing master fit the types described in chapter x as cosmopolitan and provincial.

Teaching, as the Charleston document shows, could be important to a cosmopolitan performer's career. In provincial psalmody, as the only real occupational calling, it was the cornerstone of the whole enterprise. The Calvinist branch of the Protestant Reformation had assigned music to congregations—to worshipers themselves and not

experts in the art (such as organists). By the 1720s in New England, singing schools were being founded to improve unaccompanied congregational singing. The first music published in the English-speaking colonies appeared in tunebooks compiled to serve congregations and singing schools.[20] And the first American composers, virtually all of them active as singing masters, began in the 1760s to publish their compositions in American tunebooks;[21] only in singing schools and their offshoots—meeting-house choirs and musical societies—could these composers find performers skilled enough to sing their music.[22]

Thus, in New England psalmody of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, the teaching trade absorbed functions that elsewhere existed as separate occupations: the performer, the composer, and even the distributor, to the extent that singing masters were involved with the publishing and selling of tunebooks. Psalmody was a public music, of course. But because its performance, closely linked with worship, lay almost entirely with the worshipers themselves, there was no chance for performing to develop as an independent calling. While a dollar or two might change hands for the right to print this hymn tune or that one, it was an age in which authors' royalties were unknown. There is every reason to believe that profit from printed tunebooks, if there was any, went not to compilers or composers—or even to the engravers, printers, and bookbinders who produced the book—but to the publishers who assumed financial risk.[23] The chief source of income for a musician in psalmody, then, and the sole economic niche created by the widespread singing of American Calvinist congregations over nearly a century's time, was singing-school teaching.[24]

To see the life of a New England singing master like Andrew Law (1749-1821) as the exercise of a career in music is to encounter a condition of stark scarcity.[25] Law's activities and those of most of his fellow psalmodists dramatize a truth often overlooked: In most places on this continent, and for most people before the recent past, music-making has relied relatively little on cash. As an economy, early American psalmody was a subsistence enterprise. Religious zeal combined with social aspiration and musical responsiveness to attract scholars, the customers whose tuition fees funded the singing school. Drawing upon the energy and dedication of its participants, the singing school required only enough money to secure a steady supply of teachers. There is no evi-

dence that it produced additional capital.[26] Masters who aspired to more profitable careers moved on to other trades. Andrew Law himself was an unusually energetic and strong-minded man—a born reformer with enough stamina to survive half a century of singing-mastering. Yet Law, like his contemporaries, was constrained by the acute scarcity of the economy in which he worked.

When Waldo Selden Pratt wrote, early in the twentieth century, that the authors of earlier American tunebooks "had no ambition except to serve an actual musical situation as they knew it,"[27] he must not have been thinking of Law or Andrew Adgate, two psalmodists who, in the early Federal period, harbored visions of their field as an agent of religious and musical change.[28] Pratt was right, however, about the outcome of these men's efforts. Both Law and Adgate come down through history as men who struggled bravely and vainly: Law to reform American musical taste and Adgate to fund singing schools through concert proceeds. Perhaps they failed for different reasons. But both lacked cohorts who might have aided their cause, as well as economic capital which might also have provided the means for success.[29]

While it may seem strange to equate discipleship with money, in an economy like that of early American psalmody the two had much in common. They were the only resources that might have enabled the chief agent—the musician with a vision of change, a desire not just to serve an existing situation but to alter it—to extend his influence. Discipleship, by increasing the number of spokespersons, helps to communicate the chief agent's message; money enables the chief agent to hire others to do routine tasks, leaving him free to devote more attention to extending the reach of his enterprise. So powerful is the hold of music over those who love it that many American musical enterprises have, in effect, been subsidized by the devotion of the musically inclined—by those willing to trade their energy and skill not for money but for the worthiness and pleasure of serving the cause. As it happened, Law's goal of musical reform was achieved in New England in the years 1805-10, not through his own efforts but because a coalition of religiously motivated disciples appeared in those years, steering psalmody toward a more Europeanized style.[30] This was not an economically driven reform. Rather, it resulted from the effective coordination of par-

ticipants' energies. But money did play a key role two decades later in a development that profoundly reshaped the teaching trade. Because one music teacher found, first in psalmody and then in teaching itself, an economic potential far beyond anything his predecessors imagined, the course of American musical economics, and hence of American musical life, changed dramatically during the third and fourth decades of the nineteenth century.

Lowell Mason (1792-1872) has long been recognized as an important figure in American music, and for good reason. Indeed, once we understand the economic context of psalmody that Mason inherited, his use—indeed transformation—of that economy reveals him as a musician uncannily in tune with the aspirations of his public. A Massachusetts native, Mason attended singing school as a youngster, and he also learned to play several instruments.[31] In 1812 he left his home town of Medfield for Savannah, Georgia, where he was employed first in a dry goods store and then as a bank clerk. He maintained his involvement with music by leading church choirs and studying harmony and composition with Frederick L. Abel, an immigrant musician. It was also in Savannah, while still in his late twenties, that he compiled his first tunebook.

Mason's compilation was noteworthy for its content but even more for the circumstances of its publication. Much of the music he had chosen came from William Gardiner's Sacred Melodies, from Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven (London, 1812-15), whose appeal lay in its adaptation of melodies from great European masters like Handel, Haydn, Mozart, even Beethoven, to English hymn texts.[32] Bearing his manuscript, whose stylistic consistency and purity were unusual, Mason visited Boston in the autumn of 1821. There he approached the Handel and Haydn Society, founded in 1815 to improve musical taste through performances of sacred works by European masters.[33] The society agreed to sponsor his collection for an equal share of the profits.[34] Appearing first in 1822, The Boston Handel and Haydn Society Collection of Church Music was a resounding success. It went through nearly two dozen editions, and proceeds from its sales helped to support the society's activities for years to come.[35] It also earned a considerable sum for Mason—according to Pratt, $12,000 by the time the last edition appeared (1839).[36] In 1827, Lowell Mason, now thirty-five years old and thanks to his tunebook at

least $2,000 richer,[37] left Savannah for Boston, where he assumed leadership of several Congregational church choirs and was elected president and conductor of the Handel and Haydn Society.[38]

So far, Mason had worked chiefly as a musical amateur: During his fifteen years in Savannah he was always employed outside music as well as in it. Nevertheless, his success there as a teacher (i.e., choirmaster) and distributor (i.e., compiler and copublisher) of music enabled him to enter the ranks of American psalmodists at a high level of income when he moved north. Not long after Mason's arrival in Boston, he detected fresh opportunities. As Pratt notes, the public school "was first establishing itself as an institution" at precisely this time.[39] Mason, who together with most psalmodists of his day felt duty-bound to "correct" the prevailing musical taste, grasped the advantages of teaching music to young children before their taste was formed. Earlier singing schools had welcomed teenagers and adults, but no one had ever concentrated on children. By doing precisely that—by forming a children's singing school, where receptive youngsters could learn to appreciate "good" music as they developed their skills—Mason saw a chance to strike a blow for musical improvement. Not incidentally, by extending his work beyond churchly institutions, he could also enlist new customers for his teaching and publications.

Mason refocused his energies without giving up his place in psalmody.[40] He kept one church post (organist and choirmaster at Lyman Beecher's Bowdoin Street Church, 1831-44, then at the Central Congregational Church, 1844-51) and remained active as a sacred compiler,[41] though he did resign the Handel and Haydn Society presidency.[42] Forming a singing school especially for children, he taught it free of charge and watched it grow in a few years from a class of "six or eight" to one of "five or six hundred."[43] A key to the school's success was Mason's donation of his services, made possible, at least in part, by the economic independence he had won working outside the field of music and from profits on his first tunebook. Mason's procedure was ingenious and effective. Spotting the need for a teaching service for which no niche existed, he volunteered to provide it without pay. Once he had demonstrated its worth, aided by a public performance,[44] he helped sponsors set up structures to support the new service on a paying basis. He also brought out new tunebooks aimed at his new customers.[45]

By 1832, a decade after his first sacred tunebook had appeared, Mason had embarked fully on the second phase of his musical career in Boston. A year later, in collaboration with George James Webb, Mason founded the Boston Academy of Music, centered chiefly on the teaching of music, both sacred and secular.[46] The next year, Mason began to offer teachers' classes through the academy,[47] and his Manual of the Boston Academy of Music (Boston, 1834; eleven more printings by 1861) was published to serve those classes.[48] In 1837, following a precedent that had served him well in the past, Mason took what has been widely considered the most historically significant step of his life: He offered free music classes in one of Boston's public schools.[49] The success of that volunteer experiment helped to establish music as a regular school subject, and it won Mason the post of superintendent of music in the Boston school system, a job he held from 1838 to 1845, when the Massachusetts State Board of Education named him to the staff of its teachers' institutes. Mason continued to teach music in the Boston schools until 1851, when he was fifty-nine years old, and he participated in the teachers' institutes until 1855.[50]

The facts of Mason's career trace a path from sacred to secular and from scarcity to abundance. Entering the subsistence economy of psalmody as the compiler of a sacred tunebook, Mason struck an agreement that brought him capital from its publication. Having earned a profit from psalmody, he could expand his range beyond it without having to depend upon new endeavors for his livelihood. Mason's first master stroke was to enlist a prestigious organization to back his debut as a tunebook compiler. Then he anticipated that vast economic gain was possible through secular education. But the crowning achievement of his later years was to target music teachers rather than music students as his chief customers. Mason's career shows a knack for assessing a rapidly changing situation while also participating in it. Hence, he was able to locate his own occupational activity in ever-widening contexts, each new stage increasing his clientele and influence. In the 1830s, without discarding the framework of psalmody, he broadened it gen-erationally, courting hordes of future customers. Then, having made himself the first American expert on how young children learned music, he enlisted and trained as disciples the teachers of those children, supplying them not only with ideas and techniques but with publications to meet their needs in the classroom. By the 1850s, rather than "serv[ing]

an actual musical situation as [he] knew it," as Pratt put it, Mason had helped to create a new one, supported by a growing trade network that he himself had invented.

Mason's erstwhile colleague George Frederick Root (1820-95) told a story about Mason that shows the latter's economic savvy at work. According to Root,[51] William Woodbridge convinced Mason that he should try to apply Pestalozzian principles to teaching vocal music. "If you will call together a class," Woodbridge promised, "I will translate and write out each lesson for you . . . as you want it, and you can try the method; it will take about twenty-four evenings." Mason agreed, and the class was assembled in "the large lecture room of Park Street Church, Boston." Root does not give the year, but it must have been early in the 1830s.[52] "Speaking to Dr. Mason once about this remarkable class," Root relates, "I asked him what those ladies and gentlem[e]n paid for that course of twenty-four lessons. 'Oh, they arranged that among themselves,' he replied. 'They decided that five dollars apiece would be about right.' 'And how many were there in the class?' He smiled as he answered: 'About five hundred.' "[53] The class, Root says, "was composed largely of prominent people of the city who were interested in musical education." If Mason could turn another man's suggestion into a more than comfortable yearly income for just twenty-four evenings of work,[54] it's clear that his earlier coup with the Boston Handel and Haydn Society Collection of Church Music was more than beginner's luck. Mason's was the first career that revealed American music, potentially at least, as a profit-making enterprise.[55]

The economic perspective offers a good vantage point for understanding the impact of Mason's career. In the musical environment he inherited, the pervasive issue was how music could best serve religious devotion. Giving much energy to that cause throughout his life, the devout Mason left behind a deep legacy in sacred music. But Mason's transforming insight was to recognize psalmody as part of a larger world of music, one of many worthwhile kinds of American music-making. Once he grasped that fact—once he perceived music as a realm that contained psalmody rather than one contained by religion—Mason extended his professional reach. Music-making, his insight taught him, was not only an indispensable way to enter a state of grace in worship. It was also a pleasurable human activity: a wholesome, enjoyable way to spend leisure time, and a gratifying social pastime. And a society growing

more urban and middle class was beginning to find the accessibility of musical experience a more urgent matter than the devotional concerns of an earlier age. Teaching, Mason perceived, could be the key to accessibility. If Americans were steered toward music as youngsters—if they were shown how to sing and to read notes, and provided with simple, attractive, affordable pieces to perform—the pleasures of making music would be open to them for the rest of their lives. A musician who understood how to teach children, who could convey that understanding to other teachers, and who could supply music that beginners would enjoy singing could benefit society while at the same time finding more customers than earlier American music teachers ever dreamed of.

Mason's career points the way to certain formative patterns in American musical life. It dramatizes the significance of teaching as the American musical occupation. It shows how one occupational calling can provide a framework in which others can develop. And it reveals that American music, at first strictly a subsistence enterprise, was transformed into a capitalistic one by discovering a musical service or artifact for which demand is large, pricing it within many customers' reach, and keeping control over the surplus income that results.[56] The implications of the latter point have shaped the American music business in many of its manifestations since Mason's time, especially in its tireless cultivation of arenas of demand. Surely it's worth noting that, while Mason himself got rich through a shrewd use of opportunities within the teaching trade, other musical callings can be much more profitable. But if teaching offers even its successful practitioners lesser rewards than some other callings, the pervasive and continuing demand for it has given teaching considerable economic power, which has helped it to foster an immense range of American musical activity.

Changes in the teaching trade during and after Mason's time reflect new demands. Private teaching broadened its sphere considerably. On the cosmopolitan end, it grew more specialized and, as conservatories and college music departments sprang up after the Civil War, began to provide high-level training.[57] Moreover, the activities of both private teachers and singing masters grew more diversified.

The role of the private teacher, restricted in the eighteenth century mainly to the secular cosmopolitan tradition, found a new focus during the nineteenth, chiefly in response to the boom in middle-class home music-making. Chapter 5 will take up this issue in more detail. But for

now, it's worth noting that with the creation of a vast repertory of songs and instrumental pieces—composed or arranged with the skills of American musical amateurs in mind, published and sold in sheet-music form, supported by the successful design and marketing of affordable pianos— the middle-class American home was turned into a center of musical performance and a prime market for the music business. The aspirations of this new set of performers were served by a new corps of private teachers.[58]

As for the singing class and the provincial singing master, both survived in their earlier forms in certain regions; the farther from the influence of urban centers, the more likely they were to continue.[59] (Washington Irving invented Ichabod Crane, a singing master, in 1819.) Mason's efforts helped to separate the singing class from its sacred origin and install it in the public school, where it has maintained a place to the present day. A roughly parallel process took place somewhat later in instrumental music. Early in this century, the instrumental ensemble, and especially the wind band, perceived as a wholesome, constructive, group enterprise for youngsters, was also embraced by the public school, creating a need for bandmasters and instrumental teachers as well as vocal ones.[60]

The sharp increase in the number of Americans seeking musical instruction widened the range of occupational skills and expectations of the musicians who taught them. At one end of the spectrum stood the Edward MacDowells and Horatio Parkers, hired in the 1890s by prestigious universities as professors chiefly because of their work as composers. At the other stood the school master or marm whose professional credentials consisted of attendance at a "normal institute," a summer residency program that trained music teachers in a few weeks' time.[61] Somewhere in between stood men like W. S. B. Mathews, the historian of American music we met in chapter 1, whose activities reveal the American music teacher in a role familiar today: the inveterate scrambler whose livelihood depends on energy, versatility, and tight scheduling. Writing in 1859, Mathews described in Dwight's Journal of Music his own activities—typical, he said, for a music teacher "out west."[62] In a single week, Mathews gave twenty-eight private lessons on the piano or melodeon at 50 cents each, taught three singing schools in three different towns at $1 per scholar for twelve sessions, led three choir rehearsals and two public-school music classes, and presided on

Sunday at four worship services. Mathews, it should be noted, was twenty-two years old when he fired off this dispatch. Whether or not he eventually suffered what a later age has come to call "burnout," by the time he was thirty he had settled in Chicago as a church organist, editor of a music periodical, music critic, and prolific writer on musical subjects. Teaching for Mathews, and for many other American music teachers as well, was a stepping stone, a way to maintain musical skills and to survive as a musician while remaining alert for new opportunities.

The more specialized the musical skills taught, the more expert command a teacher needs, and the more likely it is that teaching will occupy a secondary rather than a primary place in the teacher's musical aspirations. In this century, the teaching trade has broadened to encompass other specialties. Financial support, both public and private, has grown for conservatories and university music departments staffed by musicians who, while instructing student performers, conductors, composers, scholars, and teachers, are expected also to carry on their own specialties at a high level of competence. The presence of such specialist-teachers has allowed these institutions to build professional composing, performing, and writing about music into their educational programs.[63]

The link between higher education and the professions of music deserves more comment. In some academic environments, musicians who teach for a living maintain another musical profession outside the academy. Colleges and universities have also helped to bridge the gap between the professions and patronage by supporting things—compositions, performances, scholarly research and writing—that cannot survive in the marketplace.[64] Such activities are accepted not so much because society values them but because they are carried on in the name of education. They reflect public approval of the more conspicuous results of teaching, from opera performances and orchestral concerts to glee clubs and marching bands. Or, more precisely, they reflect public trust that good teaching lies behind these public successes. Many skillful musicians have found in teaching a way to buy time for their own work. Lowell Mason's career is simply one of many illustrations that, more than any other musical occupation, teaching has stretched the framework within which American musicians find employment. Since the eighteenth century, teaching has touched upon, overlapped with, infused, and in some cases subsumed other occupations for which demand has been less direct.

In some academic settings the position of teachers recalls that of musicians under European patronage: They are supported by private or public funds and given the freedom to pursue their own professional ends as long as their teaching gets done. This freedom has been won not by official decree but more gradually and indirectly: by the efforts of musicians working on two separate fronts over several generations. On the one hand, by teaching students how to sing and play and teach music themselves, colleges and universities have responded to society's direct musical needs. On the other hand, by using teaching as a way to subsidize performance, scholarship, and composition—as Roger Sessions and his compatriots have discovered—the academy has helped to create an appetite for more and more specialized instruction and a protected niche for music outside the marketplace.

I have claimed teaching as the foundation of the American music business and hence of much in American musical life; perhaps now we should look at the bedrock on which the foundation itself rests—the most fundamental musical calling of all. Composition, or musical authorship, is the act that sets Western music-making in motion. Other musical occupations depend upon it, for all music must be invented sometime by somebody. And yet, in the United States, composing can hardly be said even today to provide a real livelihood for many, as other occupations have.

From the very beginnings of musical commerce on this side of the Atlantic, there was little chance for composing to become a livelihood, not to mention a profession. In the eighteenth century, American performers, teachers, publishers, and instrument makers each had their own special concerns. But all could take it for granted that music was available in ample supply—music from the British Isles and the European continent. The needs of Old World people and institutions brought this music into being. Oral tradition and written notation circulated and preserved it. It was composed by musicians in Europe, some of whom were able to pursue composing as a substantial part of their own occupation. Americans, too, began to compose in the eighteenth century, but they did so almost entirely outside the music business.[65] Why? Chiefly because the ready supply of European music made American compositions unnecessary to the functioning of the other occupations.

Composers in America have earned money by writing music only at points where the supply of music from the Old World has failed to meet American needs .

The problem of composing as a way to make a living lies in the nature of musical notation. As the means by which composers fix, communicate, and sell their music, musical notation is indispensable to composing as a profession.[66] Yet, by preserving and circulating music in the absence of its composer, notation complicates the role of musical authorship. Once performers get hold of scores they can read, the composers of these scores become superfluous to them. While teachers, performers, publishers, and the rest find employment by acting in the present, the composer lives in a less time-bound arena; for notation brings into the present music that people wish to play or sing. Performances exist in the present, or at least they did before recordings. But the notation upon which performances depend can be supplied from other times and places. To make a living as a composer, one must therefore compete successfully not only with one's contemporaries and compatriots but also with one's predecessors from elsewhere in the world.

Since the eighteenth century, Americans have been amply supplied with music by European composers. This European legacy has been fundamental to American musicians. It has also helped to shape the working life of composers. To illustrate this point, let's look at a career that comes as close as any to marking the start of composing as a profession in the United States.

Alexander Reinagle, son of a professional trumpeter, was born in Portsmouth, England, in 1756 and established himself as a harpsichord teacher in Glasgow by 1778. Around 1784, he traveled to Hamburg, where he met C. P. E. Bach, with whom he later corresponded. The Royal Society of Musicians in London admitted him to membership the next year. In the spring of 1786 Reinagle sailed for New York and, after spending two months there, moved to Philadelphia, where he settled. Reinagle taught privately and gave concerts over the next several years. Then, early in the 1790s, he became comanager of the New Company, a Philadelphia-based theatrical troupe for which the city's famous Chestnut Street Theater was built in 1793. From his seat at the pianoforte, Reinagle presided over the music in the New Company's performances. Behind the scenes, he served as the company's chief composer until he moved to Baltimore in 1803. Reinagle died in 1809.[67]

During his early years in America, Reinagle's own compositions served him in the public performances he gave. He organized benefit concerts for himself in New York and Philadelphia, participated in other musicians' concerts, and also presented subscription concert series in both cities. His programs, which contain listings like "Sonata for Pianoforte by Mr. Reinagle," testify that he often played his own keyboard works in public. He also conducted his own overtures, played his own violin compositions, and even sang songs that he had composed.[68]

Reinagle's published music reveals his right to a special niche in the evolution of the professional composer's role in the United States. When he arrived in the New World in 1786, no such thing as an American music publisher existed. Printed music in the cosmopolitan tradition was imported from abroad; the typical domestic musical publication was the sacred tunebook, brought out by book publishers. However, by the time Reinagle assumed his theatrical duties, several American music publishing firms had entered the business. The American music publishing trade, in fact, was born in Philadelphia while Reinagle was working there as a freelance musician. Its founding and Reinagle's presence were no coincidence. For between 1787 and the beginning of 1793, sheet-music publication in this country took place only in the shop of John Aitken, a Philadelphia engraver and silversmith. Aitken issued sixteen works in those six years, chiefly songs and keyboard pieces. As Richard Wolfe has shown, all but four of the sixteen were either composed by, arranged by, or printed for Alexander Reinagle.[69]

Reinagle's compositions are not the only evidence of his involvement in the American music publishing trade from its very beginning. In a newspaper announcement soon after his arrival in New York, he advertised for pupils "in Singing, on the Harpsichord, Piano Forte, and Violin," and he added that he proposed "to supply his Friends and Scholars with the best instruments and music printed in London."[70] This suggests that he left England planning to act as a New World representative of London music merchants. Wolfe has also shown that the punches Aitken used in his shop were of English design, and he speculates that Aitken may well have acquired them through Reinagle in his role as London publishers' agent.[71]

The opening of music publishing shops in America was a key event in the establishment of composing as a profession. As suggested above, not until music was notated and put into salable form for circulation

did it become a commodity that could be bought and sold. Only if the composer participated in the publication process, as Reinagle apparently did in his work with Aitken—sharing at least some part of the financial risk—or, as was more common later, struck a royalty agreement with a publisher, could he hope to profit from his labors.[72] I have said that composing in America became a profession only at points or in genres where the supply of music from the Old World failed to meet American needs. As it turned out, the American music publishing trade relied heavily on Old World music during the first half-century of its existence.[73] Yet, with an American composer actively involved from its very beginning, seemingly as a prime mover, the founding of a music publishing trade opened to musicians on this side of the Atlantic a way to participate in the music business as composers.

Reinagle's post with the New Company at the Chestnut Street Theater brought composing closer to the center of his professional life than it had been earlier. Between 1793 and his death, he supplied music for more than twenty new stage works; he also composed and arranged songs, and he wrote overtures, incidental music, and orchestral accompaniments for theatrical works by other composers. Almost all of Reinagle's theater music was later destroyed in a fire, so that side of his work is mostly inaccessible today. But the music that does survive provides a good idea of what was expected of its composers.

Music in the eighteenth-century Anglo-American theater served as a pleasant, entertaining embellishment to the story acted out on stage, much of which was carried on in speech. The ability to write graceful tunes with clear text declamation, to highlight the vocal strengths of the company's performers, to provide effective orchestral accompaniments, to know what to borrow from other composers and where to place it for strongest dramatic effect, to work quickly and efficiently under pressure, and to accept one's subordinate place in the whole enterprise—these were the traits valued in a composer in this position. All indications are that the musical tasks for which the New Company employed Reinagle were more or less routine for a composer of his skill.[74]

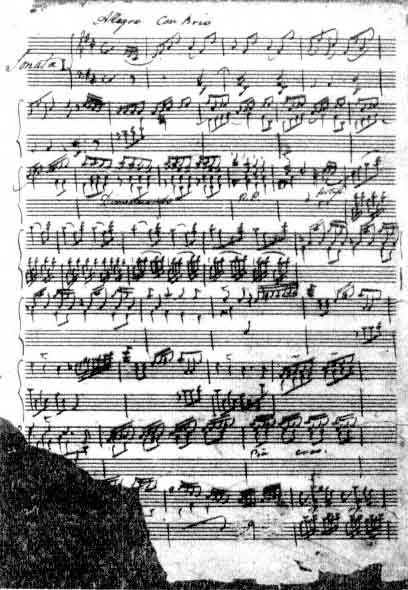

With Reinagle's career in mind, let's look at two examples of his music. Figure 1 is the first page of a piano sonata he composed in Philadelphia, probably between 1786 and 1794;[75] it shows his command of the keyboard idiom of eighteenth-century European masters.

Figure 1.

Folio IV, opening page of Sonata No. 1, from Reinagle's autograph

manuscript, ca. 1800 (Library of Congress ML96.R28)

Example 1.

Reinagle, "America, Commerce, and Freedom," bars 28-42

(The Sailor's Landlady [1794]; after H. Wiley Hitchcock,

Music in the United States [Englewood Cliffs, N.J., 1969], 29)

Example 1 is part of a song Reinagle wrote for the ballet pantomime The Sailor's Landlady (1794).[76]

By almost any accepted standard of aesthetic judgment, Reinagle's sonata is a more impressive piece of music than his song. Yet the sonata never found its way into print until 1978, while there is every reason to believe that "America, Commerce, and Freedom" was published immediately after it was composed.[77] Why should a good piano sonata lie neglected while a routine song by the same composer is printed and offered for sale to the public? Because in eighteenth-century America there was a healthy market for songs and almost no market for piano sonatas. Songs were short, melodious, inexpensive, and they had words—all appealing traits to the amateur performers of the time who bought sheet music. The theatrical context of songs added to their attractiveness: One could hear a song performed onstage, buy a copy,

and sing the song at home oneself. Sonatas, on the other hand, were reserved for more accomplished musicians. Mastering a sonata required skill, practice, and, most likely, lessons. Besides, players who were technically accomplished could buy music by European masters like Handel, the sons of Bach, and Haydn himself. Who needed a piano sonata by Alexander Reinagle? Reinagle's own answer remains elusive, for his four sonatas stayed in manuscript for nearly two centuries after he composed them.

In Reinagle's two compositions may be read the divided heritage of composing as a profession in the United States. Reinagle the composer with intellectual autonomy and authority appears in figure 1, Reinagle the composer with economic muscle in example 1. The gap between composing as a profession of the kind Virgil Thomson has described and composing as a livelihood is dramatized by the differences between the two pieces. In the sonata, Reinagle exercised technical command and seriousness of artistic purpose for their own sake, unconnected with economic potential. In the song, technique and constructive power yielded priority to making a tuneful surface to catch the public ear.

Having noted the professional implications of Reinagle's sonata and his song, we may consider something else about the way notation has functioned in American musical life. Here we must be careful not to speak about written music as if it were simply one thing. For there are actually two distinct kinds of written music, illustrated by Reinagle's two pieces.

The first kind, exemplified by the sonata, is what both Thomson and Jacques Attali describe as a normative musical composition. Here a composer invents a piece of music and writes down his or her instructions in enough detail that it can be played or sung precisely as the composer has conceived and imagined it. The performer, in turn, accepts the composer's score in an attitude of deference and strives to carry out the latter's instructions as closely as possible. In the second kind of written music, exemplified by Reinagle's song, things work differently. The composer's score is far less detailed. And its lack of detail is an invitation for performers to sing or play it any way they like. Some performers might want to simplify or decorate the written version. Some might prefer it in a different key. Some might accompany it with cello or guitar, or with the final keyboard section left out, or lengthened, or sing it with no accompaniment at all, or at a very fast clip or a slow

one. Departures from the score like these would be unacceptable in the sonata; they would change its very nature. But in the song, they would hardly be noticed. For the score of a song like "America, Commerce, and Freedom" is understood not as a finished statement but an outline to be filled in, to be "realized," by performers in any way they choose.

In an article published some years ago, I called the first kind of written music "composers' music" and the second "performers' music."[78] I did this because I felt uneasy with the standard polarities— "classical" and "popular," or "cultivated" and "vernacular," or "serious" and "light" music—because they seemed more categorical and value-laden than a historical view of music would support.[79] With the typology of "composers' music" and "performers' music" in mind, it's clear that professionalism's different elements pulled Reinagle in opposite directions as a composer. "Performers' music" like "America, Commerce, and Freedom" offered the chance of pecuniary success but no authority over its performances. "Composers' music" like the piano sonata offered intellectual autonomy at the price of economic potential. Reinagle's two pieces reflect the structure of a divided profession: To compose either composers' or performers' music was to forfeit one of the profession's traditional perquisites, whether it be technical control or economic reward. By writing both, Alexander Reinagle managed to exercise in his compositional mind, if not embody in his music, the full range of a professional composer's opportunities and obligations.

If composing became a livelihood in America only where the supply of music from the Old World failed to meet American needs, we can see that it has been in performers' music, not composers' music, that the Old World has fallen short. American composers of performers' music—from Reinagle's "America, Commerce, and Freedom," to Stephen Foster's "Old Folks at Home," to W. C. Handy's "The St. Louis Blues," to Irving Berlin's "White Christmas," to Bob Dylan's "The Times They Are A-Changin' "—are the composers who have won a secure place in the American music business. By appealing to the tastes and adapting to the talents of many performers, the music of these men has established them as "professional" composers in an economic sense if not in the full sense of Thomson's intellectually based hierarchy.[80]

Having noted the importance of performers' music, let's look again at composers' music—at Reinagle as a writer of piano sonatas and at Sessions and company as writers of music for the concert hall—and

examine its professional heritage. During the nineteenth century, as in the eighteenth, American composers' music existed mostly outside the music business. This did not discourage Americans from composing it, any more than Reinagle was stopped from composing sonatas because sonatas were unmarketable. In fact, the widespread impulse to compose is a striking feature of nineteenth-century American musical life. Scratch an organist, a pianist, even a historian, and you find a composer with a drawerful of songs, sonatas, concertos, cantatas, symphonies.[81] Little of this music was professionally motivated. But there it stands—or, rather, lies: testimony to the industriousness of its authors and of their urge to contribute their own mite to the tradition of the European masters.

The twentieth century has seen the gradual alienation of many composers of composers' music from other musical trades and occupations and from much of the concert-going audience as well. Yet alienation has not dampened the urge to compose. The writing of new composers' music goes on at what seems like a quickening pace, and all over the United States composers are hard at it, pouring their creative efforts into works that may never be heard, except in their own imaginations. This state of affairs suggests that complex, even contradictory impulses are at work. One step toward sorting them out is to distinguish between the profession of composer, the role of the composer, and the place of the composer, considering them as three different though complementary things.

Thomson described in 1939 how American composers make a living: "[the composer] plays in cafés and concerts. He conducts. He writes criticism. He sings in church choirs. He reads manuscripts for music publishers. He acts as musical librarian to institutions. He becomes a professor. He writes books. He lectures on the Appreciation of Music."[82] Conspicuous by its absence from the list are the words "he writes music." Perhaps the range of duties has changed a bit in the half-century since Thomson wrote. But the principle remains the same. As has been true since the time of Alexander Reinagle, the profession of composer of composers' music is only indirectly linked to a livelihood, and almost all such composers earn their keep by doing something else.

What about the role of composer? The question answers itself, for what nation would admit that it has no composers? Certainly we have composers: hundreds, even thousands of them. And we are knee-deep

in composers' music.[83] Perhaps, as in the nineteenth century, the supply would have been assured in any case. But something new has appeared in the twentieth century: an institutional commitment to supporting the role of composer. This commitment is reflected by the beachhead that composers have won in the academy, the preserve gained by teaching. It is also reflected by patronage—in earlier years devoted almost entirely to supporting performers in the concert hall and opera house—which in our century has begun to be available to composers.

During and after World War I, as the reverberations from radical movements in Europe began to reach American shores, a few modernist composers, rejected by the concert establishment, managed to find patrons, as in Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney's support of Edgard Varèse, or Harriette Miller's of Carl Ruggles, or Alma Wertheim's of Aaron Copland and Roy Harris.[84] But more typical has been the institutional patronage that began in the 1920s. In 1925, for example, Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge established at the Library of Congress an endowment for commissions, prizes, and concerts, with the funds open to European and American composers alike.[85] Beginning the same year, the John Simon Guggenheim Foundation offered the first of the year-long stipends it has since granted to North American composers.[86] Then there is the Fromm Music Foundation, established in 1952 to commission, record, and sponsor repeated performances of new works.[87] Other private agencies, such as the Ford[88] and Rockefeller Foundations,[89] have also supported and commissioned new works from living composers. As for the federal government, whose earlier support of music had been limited to the military (since the end of the eighteenth century)[90] and the depression-inspired relief measures of the WPA (1935-41),[91] it established its own program of composers' patronage in 1965 when the National Foundation on the Arts and Humanities was founded.[92] These programs, and others like them, distribute funds on a revolving basis, treating applicants' claims to patronage as more or less equal and rewarding them after they take their turn in line. The way the programs are administered testifies at once to their commitment to supporting and maintaining the role of composer and their democratic reluctance to favor any single composer.

If the role of the composer of composers' music is firm, their place in our musical life is small, and the shadow they cast over the American musical landscape is hard to detect. Place means presence, and in music

presence means performance. In New York and a few other large cities, and on some university campuses, the composer's place is established by the chance to hear his or her music. But outside these circles, with their groups of specialist players, who, incidentally, make their way chiefly by other professional activity, that music is hardly heard at all, and composers exist chiefly as representatives of an honored role, their work reviewed and cataloged but not much relished.

In the field of American composers' music today, the imbalance between composers' honored role, their neglected place, and their almost nonexistent profession is striking. These different dimensions reveal our society's respect, in principle, for what composers are and what they do: talented, dedicated musicians who, as the heirs of Beethoven, maintain the legacy of past glories while also exploring new worlds of sound on society's behalf. At the same time, they reveal an indifference, perhaps even a hostility that amounts to a rejection of the experience that modern composers' music offers.

How does modern society treat something it respects but does not savor? The way we have treated most twentieth-century American composers' music: by finding a safe place for it. Composers' music by Americans—supported by various kinds of professional arrangements (including performing-rights income),[93] complemented by a modest but steady flow of patronage in the form of commissions, prizes, and fellowships—exists today in an environment like that of a laboratory. I borrow the analogy in part from Milton Babbitt, who once likened the "specialist" academic composer to the theoretical mathematician or physicist.[94] I'm also under the impression that labs, even when funded by laypeople, are run by experts, who evaluate how the lab's work is going. That's a way of pointing toward a noteworthy development among American composers of composers' music since World War II: the winning of autonomy—the right to compose essentially outside the strictures of audience esteem, or critics' approval, or the tastes and preferences of performers.

Autonomy has expressed itself in a feeling that, as Thomson suggested half a century ago, composers are perhaps the best judges of each others' works, even to the point of dispensing patronage, for the benefactions that reach composers are dispensed, at least in part, with the advice of a review of peers. Composers' music is thus composers' music both in its premise that the score controls the performance and

in the narrowness of the world it inhabits—a world of composers and a small number of specialist-theorists who know their work. This is not to say that composers would spurn the chance to be heard and appreciated by a much larger audience. It is merely to recognize their lot. Through hard labor and the acceptance of a lofty, lonely vision of their calling, they have carved out for themselves an autonomous niche within the broader world of musical professions, occupations, and patronage. Most American composers of composers' music seek a home within that niche. Finding such a home depends chiefly on how good the composer is at addressing fellow composers. In other words, composers of composers' music today write the kind of music that they are commissioned, supported, and expected to write.

Historians concentrate on what is lasting, and in music history the score lasts long after the sounds of performance have died away and the memories of personalities and public careers have faded. That's one reason that music historians have concentrated on musical scores. We earn our methodological spurs by grouping scores for study and interpreting them as distillations of musical life—as, in effect, what matters most about a given musical culture.

Musical scores, however, can distill not only music itself but the context within which music is made—not only the musical style, the artistry, and the aesthetic achievement of composers but the impact of a musician's livelihood upon his or her music-making. As Virgil Thomson argued half a century ago, in essays called "How Composers Eat" and "Why Composers Write How: Or the Economic Determinism of Musical Style," in the United States, where music reflects the pressures of the marketplace, money and musical style are closely intermingled.[95] The scores of a forgotten composer like Alexander Reinagle may seem remote from present-day concerns. But if we can understand them as reflections and distillations of a professional environment that has shaped the particular, idiosyncratic patterns of American composition, then we can begin to recognize the continuity of our country's musical history and to see Reinagle, and Roger Sessions, and today's composers of composers' music as musicians linked in a tradition that began on this side of the Atlantic at least two centuries ago.

3

Professions and Patronage II: Performing

Performing has been the most conspicuous American musical profession and one of the most profitable. The musicians best known to the public have been performers. But behind the limelight of public regard, it must be remembered, musical performance is a distillation: the public result of many different agents' endeavors.

In the professional realm, the public concert[1] is the emblematic event, for it is there that musical effort comes to fruition. A composer's invention, a teacher's regimen, an instrument-maker's labor, an entrepreneur's search for a forum, a critic's judgment—all, in a professional sense, revolve around the moment when performers sing or play music for the public to hear. For it's up to the performer to seize the occasion and, through artistry, technique, intellect, and personality, connect with an audience. In that connection lies the ultimate power of Western music-making. Performers risk much. But their intensely competitive profession offers rich rewards in money and fame.

Famous performers have been among the most fascinating American public figures, and few musical subjects are more ineffable than the relationship between them and their audiences. What makes a star performer? How can the "magic" of an excellent performance be described? Much has been written about performers—especially their lives and personalities—with questions like these in mind. Yet answers have remained elusive. Perhaps the reason is obvious. Because musical performance seeks connection, it is often judged less by what performers do than by how they are received. Therefore, writings that concentrate on performers without considering the audience and what it expects from them leave these questions unanswered.

To think of audiences and their reception of performers is to recognize that music is a particular kind of human interaction as well as an art. But how, in America, did audiences for music come to exist in the first place? In a country lacking the institutions that in Europe sponsored musical performance, other means of support had to be found.[2] Without opportunities to sing and play for pay, there can be no career for a performer. The creation of such opportunities is itself an occupation—the arm of musical distribution that brings performers together with audiences. Entrepreneurship is intertwined with performing so completely that neither can exist without the other. In fact, impresario, performer, and audience are bound together in a round of negotiation driven by the impresario's pursuit of economic gain. French pianist Henri Herz, who toured the United States in the 1840s, attributed to his American manager Bernard Ullman a definition of music that was obviously intended to sound cynical. In Ullman's mind, Herz wrote, music was "the art of attracting to a given auditorium, by secondary devices which often become the principal ones, the greatest possible number of curious people, so that when expenses are tallied against receipts, the latter exceed the former by the widest possible margin."[3] This definition shows little respect for either manager or audience. The latter, drawn by curiosity, cannot tell "primary" from "secondary" allurements and hence hardly deserves an artist's attention, except as a source of income. The former, knowing the audience's gullibility, seeks to exploit it for his own and the performer's advantage. The performer's artistic skill is the commodity the manager seeks to peddle. But the performer's dedication to art, Herz implies, is threatened by professional circumstances, which oblige the performer to do whatever it takes to occupy a curiosity-seeking audience, lured into a concert hall by the blandishments of a money-driven promoter. Thus, Herz's mock definition of music offers an unadorned glimpse of the performing musician's profession in the mid-nineteenth-century United States.

The first performers to appear regularly before paying audiences in America were the English men and women who sang on Colonial stages from the mid-eighteenth century on, brought to the New World by theatrical managers like Lewis Hallam, Jr.,[4] and Thomas Wignell.[5] The former arrived in the 1750s and toured North America's major cities, as well as some minor ones, presenting plays and ballad operas. By the

1790s, Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Charleston all had theatrical companies in residence. Their presence established in each of these places a corps of experienced, European-trained musicians—singing actors, actresses, and orchestra players—some of whom supplemented their incomes by giving concerts (and lessons). It also made familiar the idea of public events centered on music, or at least involving it, and relying on an audience to pay for them. That audience had to be recruited, and advertising was the chief means. Newspapers carried notices of upcoming plays and concerts. Such ads proclaimed the merits of the event or, if the performers were new in town, touted their credentials. "At Mr. Hull's Assembly Room, will be performed a great Concert extraordinary," announced the New York Mercury on 16 May 1774 in a typical public invitation,[6] while in 1796 an advertisement for a concert in Charleston by "Signor Trisobio" identified him as "an Italian professor of vocal music, who had the honor to be employed three years in the Royal Chapel by the queen of Portugal and who last winter sung in London before all the royal family."[7] Advertisements ranged from the informative —these musicians performing this music at this time and place—to the promotional, often hinting that something extraordinary, unprecedented, or elevating awaited the customer. The public was being sold a chance to see and hear professionals practicing their craft, whether to dramatize real life on stage, to mock human pretensions through comedy, or to edify, divert, or amaze audiences with musical skill: beauty of tone, agility of technique, or an affecting delivery of melody and text. Many eighteenth-century concerts were followed by social dancing, which enlivened them for audience participants.[8]

Oscar G. Sonneck has documented how theatrical and concert life dovetailed in eighteenth-century America, with many of the same people—Alexander Reinagle, for example—involved in both. His studies also show that, from a professional standpoint, the "American" musical theater of the eighteenth century, like that of Bristol or Edinburgh, or even the West Indies, was an extension of the London stage. When Wignell and company sought new works or talent, they sailed to England to find them.[9] Carried on throughout the English-speaking world, this tradition remained Colonial, and not until well into the next century did American-born singers and players begin to find places in the American theater. Concert life, though more flexibly structured than the

world of theatrical companies, followed suit. Sustained by its links with the theater, it was also similar in format and repertory. Some foreign performers toured the New World, then returned to the Old. Others settled here. But more important than questions of immigration and residency was the fact that both theater and concert stage perpetuated Old World traditions. In fact, all indications are that through the first four decades of the nineteenth century, a vast majority of professional performers in America—people who made their living chiefly by singing or playing—were foreign-born.[10]

A new situation arose in the 1840s. By that time, as egalitarian ideals and technological progress moved into synchrony, economic development in the United States was shifting into higher gear.[11] Musical activity increased too, with more and more performances taking place over an ever-widening territory.[12] With a growing appetite for public performance came new theatrical forms and the rise of new varieties of entrepreneurship. In the theater, the blackface minstrel show was born. Outside it, promoters of musical attractions (like Bernard Ullman) helped to spark the increase, as did artists and troupes who by the late 1830s had begun to tour the country in search of audiences, sometimes under a manager's direction and sometimes making their own schedules and arrangements.[13] Moreover, if not new to the 1840s, local musical societies also fostered performing careers, providing occasions where amateur and professional musicians could collaborate.[14] These developments maintain some links with the past, especially in the continuing importance of the English theater and Americans' responsiveness to foreign performers and music. But the vast increase in music's potential audience and in opportunities for American-born performers, performing American music, to make a living by singing and playing signaled the start of a new era.

Theatrical managers, as holdovers from an earlier age of entrepreneurship, continued in the 1840s to house resident companies playing English opera and other dramatic entertainments. They also hosted traveling companies.[15] By all odds, however, the most significant force to hit the American performing world in the first half of the nineteenth century was Italian opera, which, from the time of its New World debut in 1825, inspired struggles of entrepreneurship on its behalf. The story of the United States' embrace of Italian opera centers on New York City, whose elite society proved neither rich enough nor sufficiently

interested to support opera on its own. Lorenzo DaPonte, who emigrated to America in 1805 and found a post as a teacher of Italian, was involved from the start. First, DaPonte encouraged Irish-born merchant Dominick Lynch to bring Manuel Garcia's troupe to New York for a season of Italian opera at the Park Theater (1825-26).[16] Several years later, he also helped to find sponsorship for a season staged by Bolognese impresario Giovanni Montresor's company (1832-33); then he and Lynch backed the building of a new Italian opera house, which opened in 1833. These efforts, like the launching of a new company by restaurateur Ferdinand Palmo in 1844 and the collaboration of 150 wealthy New Yorkers to give the new Astor Place Opera House its own company in 1847,[17] all failed to win a permanent presence for opera in the city. Not until the 1850s was success achieved. At the Academy of Music, Bohemian-born impresario and conductor Max Maretzek devised a plan in which the works of Rossini, Donizetti, Bellini, and Verdi, as well as other European masters, performed in a large hall (4,600 seats) at varied prices ($1.50 top, ranging down to 25 cents), attracted an ample base of public support.[18]