Seven—

"As Large As She Can Make It":

The Role of Black Women Activists in Music, 1880–1945

Doris Evans McGinty

In 1904, Fannie Barrier Williams, a leading African-American clubwoman, reflected on the position of the black woman with the words,

The old notion that woman was intended by the Almighty to do only those things that men thought they ought to do is fast passing. In our day and in this country, a woman's sphere is just as large as she can make it and still be true to her finer qualities of soul.[1]

Although she focused on the role of women in business affairs, Williams aptly expressed the viewpoint of many early-twentieth-century black women activists. The sphere of the black woman in music, as much as in any other field, was large—larger than historians have suggested.[2] From the second half of the nineteenth century to the end of World War II, black women were active professionally, not only as performers and teachers, doing work "that men thought they ought to do," but also as artist managers and journalists, taking on positions traditionally occupied by men. The vocational changes precipitated by the war continued into the era of peace and brought greater opportunities for all women.

While much is known about black women prominent on the concert stage from the 1880s into the early twentieth century,[3] the extent to which black women influenced the development of classical music traditions among African-Americans during these years has yet to be fully assessed. However, scattered sources such as newspapers, minutes of meetings, school records, programs, archives, and recollections reveal activities of African-American women musicians whose contributions were significant. This chapter discusses black women activists who were prominent from around 1880 to 1945, whether on a national or the most local community level, as educators, writers, and preservers of the black musical heritage. Most of these women were performers at some point in their lives, but the following discussion centers on activists in roles other than or in combination with that of performer.

Formative Conditions

As the twentieth century began, most black Americans, particularly in the rural South, lived in bleak and deteriorating social, political, and economic circumstances. Seeking better and higher-paying jobs and hoping for more acceptable living conditions, African-Americans began to move from the South as early as 1879. What began as a trickle soon developed into a flood—a massive exodus known as the Great Migration—and by 1915 numerous northern cities had sizeable black populations.[4] But the de facto segregation of the northern cities resulted in a culture within a culture, with the African-American communities establishing their own institutions and traditions as a means of survival. Black churches, masonic lodges, schools, newspapers, and colleges enhanced awareness of a distinctive subculture, while businesses dependent exclusively upon the black community took shape. From this social and economic matrix, a solid black middle class composed of businessmen and professionals emerged.[5] Within this world, black women occupied a position quite different from that of their counterparts in mainstream America. Historically, from the earliest days after the Civil War, it had been necessary for black women to contribute to the economic stability of the family because they could sometimes obtain low-paying employment when black men could not. However, gender discrimination both in the larger community and in their own, along with racism, compounded for black women the problems of work, education, and family. That composers, conductors, instrumentalists, artists' managers, and journalists were far less likely to be female than male was hardly accidental, but rather the result of widespread American attitudes—held in the black community as well—that relegated women to traditional roles. Barriers to participation in professions such as medicine or the ministry were similar to those faced by the white American female but reinforced by the racist hiring policies of many hospitals and other social institutions, and even in occupations where their numbers were large, black women were often denied positions of authority.[6] As the civil rights leader Mary Church Terrell expressed it, "The Afro-American woman had two heavy loads to carry through an unfriendly world, the burden of race as well as that of sex."[7]

In the face of these difficulties, black women developed a sense of independence that allowed them to reconcile domesticity and activity outside the home.[8] Fortunately, a relatively high degree of acceptance was accorded black women activists in music.[9]

The Community Leader

Women musicians assumed roles of leadership on several different levels: as performers in various settings (e.g., churches, schools, civic organizations, social groups, etc.), founders and directors of ensembles, and organizers of clubs. In Washington, D.C., the nation's capital, for example, women made outstanding contributions to the heritage and life of a large black population.[10]

The Church Setting

By 1900, black Washingtonians were able to look back upon a fifty-year history of interest in classical music, a tradition in which there was considerable opportunity for women to participate.[11] As centers of social as well as religious activity, the churches were the main support of concert life. Churches furnished concert auditoriums, and it was through various church clubs and committees that tickets were sold and arrangements made for musical programs. Staples of the concert season were regular choir concerts and recitals featuring local musicians and visiting artists of national stature.

Choir concerts were most popular in the Washington black community's musical season, and the choirs of the largest and oldest churches achieved national reputations. Organists, choir directors, and a few outstanding accompanists assumed leadership positions, most of which, until after World War II, were held by men. Few of these musical leaders, though, were more visible in early-twentieth-century black Washington than Mary L. Europe (1884–1947), who by 1909 was organist and choir director at the influential Lincoln Memorial Congregational Church, which presented its share of concerts and recitals, including those of its highly trained choir.

Community Organizations

Mary Europe's activity in the community was diversified. Called a "musicians's musician" by her admirers, she performed solo piano recitals and often accompanied local and visiting artists.[12] As the accompanist for the Coleridge-Taylor Choral Society, she occupied a position of special prominence, resulting from the organization's renown. When the well-known Afro-British violinist, conductor, and composer Samuel Coleridge-Taylor (1875–1912), son of a Sierra Leonean father and an English mother,[13] came from London in 1904 to conduct the society in his cantata Hiawatha's Wedding Feast , he publicly recognized Europe's fine musicianship, with the result that her reputation was considerably enhanced in Washington music circles.

Founded in 1901, the Coleridge-Taylor Choral Society had 160 to 200 voices and was, justly, a source of great pride in Washington, D.C. The idea for its creation came from Mamie Hilyer, founder of the Treble Clef Club (discussed below), although—as was often the case—her husband, Andrew F. Hilyer, a leading businessman and treasurer of the organization, and the conductor, John Turner Layton, were more prominently associated with the society in the public mind.

Mamie Hilyer had met Coleridge-Taylor during a trip abroad and had returned to the United States enthusiastic about establishing a choral group that would perform his compositions. She and her associates conceived the plan to invite Coleridge-Taylor to Washington to conduct the society; her husband carried on the main correspondence. Mamie Hilyer promoted the society through her performances as a pianist and other fund-raising efforts. Concerts of the choral society were enthusiastically reviewed by the local and national black newspapers,

and the audiences, made up of whites as well as blacks, were so large that some persons were turned away for lack of seating. A writer for the Evening Star (24 April 1903, 13) described the society's first concert as "splendid" and "an event of interest in the musical history of this city."

Ensembles and Clubs

In the first decades of the twentieth century, except for a few popular dance ensembles, orchestras and bands in Washington's black community generally did not include women players.[14] In keeping with the movement spreading over the United States, Washington women, in a few instances, developed their own ensembles. Such a group was the Corda Club, a thirty-piece women's string ensemble of mandolins and bowed strings, which presented concerts under the direction of Gregoria Frazier Goins (1883–1964) in the decade from 1910 to 1920.[15]

Another important group that offered leadership in the community by presenting annual concerts and encouraging young musicians was the Treble Clef Club, founded in 1897. Made up of professional women musicians and music teachers interested in the study of music for their own development, this group brought the "best music"—with special emphasis on that of black composers—to the community. The local respect and national regard for this women's organization were indicative, at least in part, of the effectiveness of its leadership.[16]

The Treble Clef Club was probably an outgrowth of the black women's club movement, which was solidified with the founding of the National Association of Colored Women (NACW) in 1896. The motto of the NACW, "Lifting as We Climb," was important to black women. The implied commitment to social welfare programs and self-development became the raison d'être for the establishment not only of clubs but also of educational institutions in the early twentieth century.

The Educator

If there was a common motivation for this century's pioneer black women activists, it was the conscious desire to enhance the status of the African-American. With missionary zeal, they carried on their work and repeatedly spoke of its potential to "stamp weal or woe on the coming history of [their] . . . people."[17] The ideal of assisting the needy and underprivileged was a goal shared by the white women's club movement of the nineteenth century. For white women, though, the act of giving aid to others made it possible to work outside the home without losing claim to true womanhood; for the black woman, helping the less fortunate was a necessity for all.

No group carried out the theme of self-help more than black women educators. Teaching was the profession most open to them despite low pay (smaller than that of either males or white women), regulations that excluded married women from teaching in the public schools, and gender discrimination in higher positions, and frequently women who made their mark in other areas also entered the field

of teaching at some point in their lives. A significant appeal lay in the fact that education was seen as the most important avenue of racial progress—an ideal way to expedite racial betterment.

Immediately after the Civil War, black men held most of the jobs of teaching and preaching, but by 1890 black women had become a dominant force in the educational system of southern states. The number of black women teachers grew rapidly in the South and also in the North during the exodus, so that by 1910 women outnumbered men five to one.[18]

The respect accorded music teachers enabled them not only to influence their students but also to provide assistance and guidance to other members of the community. Like Mary L. Europe, who discovered the distinguished singer Larry Winters (1915–65)[19] and guided his early study of music, they encouraged and promoted talented young musicians.

Taking the next step, educators found the ways and means of offering scholarships to assist in the education of their students. The B-Sharp Club of New Orleans, for example, organized in 1917 by pianist, singer, and teacher Camille Nickerson (1888–1982),[20] offered and continues today to provide substantial scholarship awards to aspiring musicians.[21]

Public School Teachers

In the early twentieth century, women music teachers on the high school level conducted choirs and, less frequently, bands. It is not surprising that the directors of instrumental ensembles in public schools were usually male, since American women instrumentalists received training mainly as organists and pianists or sometimes as violinists and were less likely to find encouragement to take up wind instruments. Black women instrumentalists were, however, in evidence during these years, especially in show business, and occasionally they worked in the public school system.[22]

Isabelle Taliaferro Spiller (1888–1974), orchestral supervisor at Wadleigh High School in New York starting in 1942, was a competent wind instrument performer. She studied piano in early life and continued to do so through college,[23] but her experience in performing on tenor alto, and baritone saxophone and trumpet as a member of the Six Musical Spillers, a vaudeville group formed by her husband, furnished important preparation for her position as orchestral supervisor.[24] Isabelle Spiller was also assistant manager for the Musical Spillers (1912–26) and director of the Spiller Music School, founded in 1926.

In the case of Revella Hughes (1895–1987), stage experience was both detrimental and helpful. A soprano, pianist, and organist, she organized and conducted the band of Douglass High School of Huntington, West Virginia Earlier, Hughes had trained the chorus for the road show version of Eubie Blake and Noble Sissle's celebrated musical comedy Shuffle Along (1921) and had been a star of

Runnin' Wild , a successful musical comedy by James P.Johnson (1923). According to Hughes, her show business background turned out, at first, to be a liability:

Some parents who knew that I had been in show business complained to the school board that they didn't want this show business woman teaching their children. . . . I told you that show people had an awful reputation. But I was allowed to remain in the system. I was supervisor of music for the Negro public schools, and I taught music in the elementary school and at Douglass High School. When I was ready to leave the parents begged me to . . . stay with them. Isn't life funny? When I left, I left them with a band of 124 pieces. There was $900.00 in the bank; they had uniforms and good instruments, including sousaphones. . . . When I began we had to borrow instruments from stores and organizations for our parades.[25]

Her success in producing and directing musicals and operettas that turned out to be profitable fund-raisers may have helped to convince dissenting parents that "this show business woman" was truly an asset to the community.[26]

Although the administrative level of the public education system was still, as late as the 1930s, viewed as a predominantly male province, black women music teachers—such as Spiller and Hughes—were occasionally able to infiltrate it. In Washington, D.C., from the turn of the century to 1925, three women were appointed supervisors of music in the colored schools: Alice Strange-Davis (from 1896 to 1900); Harriet Gibbs Marshall (1900 to 1905), whose further contributions will be discussed later; and Josephine E. Wormley (1916 to 1925). In Chicago, Mildred Bryant Jones (dates unknown, active from the early decades of the century to around the 1950s) influenced large numbers of students in her position as head of the music program at Wendell Phillips High School.[27]

Similarly, in Washington, D.C., the music curricula in two of three public high schools available to black youth were established by women: Mary L. Europe at Dunbar High School and Estelle Pinckney Webster at Armstrong High. But they contributed to community events in significant ways outside of their responsibilities of conducting high school choirs and teaching classes. For example, Europe and Webster were among those invited to provide music and lectures for meetings of the Bethel Literary and Historical Association, the leading cultural organization of the city. Of course, Europe and Webster, both of whom conducted private teaching studios, could expect to reap benefits from opportunities to perform or present students at Bethel Literary meetings. Attention resulting from coverage by the national press could, at the very least, add to their reputations as teachers.[28]

College Teachers

Historically, institutions of higher education offered the widest scope for the talents of women teachers, and even in the early years of the historically black colleges and universities, a few black women were hired to give instruction in music. When the Fisk Jubilee Singers set out from Fisk University in 1871 on the first of

their famous tours, which raised $150,000 for the university and popularized the African-American spiritual in America and Europe, a young pianist, Ella Sheppard (Moore), was charged with the vocal training and general oversight of the singers. She also directed them on occasion, and, when illness forced the director, George White, to resign, she took over full management of the group. Sheppard also assisted Theodore Seward in compiling the 1872 publication Jubilee Songs as Sung by the Fisk Jubilee Singers of Fisk University . These words from a eulogy published in the Fisk University News indicate the impact of her leadership: "As a leader of music, Mrs. Moore had few equals. Well do I remember, when, more than a score of years ago, she trained a Jubilee chorus in which I sang bass. We were young, life was all a dream, but she had us only a few hours when we began to realize that 'the Lord had laid His hands on' her."[29]

In the early twentieth century, black women performers were attracted to the faculties of historically black colleges and universities in surprisingly large numbers, both for financial security and for the chance to teach promising young students. Discrimination limited the possibilities for national recognition and also reduced the number of jobs available to performers. College administrators were very likely anxious to include on their faculties artists who had extensive concert experience and who had studied at American colleges and universities or perhaps in Europe. Joining forces, then, was desirable for both college and artist, as well as for the surrounding community, which welcomed increased opportunities to hear highly trained performers.

Hazel Harrison (1883–1969), the leading black woman pianist of this era, combined teaching with a concert career. Harrison, who appeared with the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra at the age of twenty-one, taught at Tuskegee Institute in Alabama (1931–34) and Howard University in Washington, D.C. (1934–59), and ended her teaching career at Alabama State College at Montgomery (1959–64). With the double limitation of race and gender, she was unacceptable to the Hurok Concert Bureau, the leading American management agency,[30] but determination led her to make whatever adjustments were necessary to continue a career as concert artist. Acting as her own concert manager, she periodically took leave from teaching to concentrate on performing. During a three-year leave of absence from Howard University, she performed some 100 concerts throughout the United States. Harrison's devotion to her students took many forms, including the use of receipts from her concerts to establish the Olive J. Harrison scholarship fund—named for her mother—at Howard University.[31]

Other examples of outstanding black women on college faculties include Maud Cuney-Hare (1874–1936), a pianist and author who served as director of music at the Deaf, Dumb and Blind Institute of Texas and at Prairie View State College in Prairie View, Texas (see further below),[32] and the singer Florence Cole Talbert (ca. 1890–1961), who in 1930 became the first black director of music at Bishop College in Dallas, Texas. As a result of successful tours in Italy, especially her appearance in the leading role of Aida at the Teatro comunale in Cosenza

(Calabria), Talbert was well known to African-American musicians. She later headed the voice department at Tuskegee College (1934–40).[33]

Founders of Institutions

Although college-level training in music was available to African-American students at historically black colleges and universities, as well as at some predominantly white music schools, such as Oberlin Conservatory and the New England Conservatory, the need for easily obtainable training in music beyond high school was often met by small local institutions. Several music schools or departments of music within schools were founded by black women during the years 1903 to 1930;[34] moreover, many music studios (sometimes called schools) were established by performers after retiring from the stage. Of the several women who founded institutions, Harriet G. Marshall (1869–1941), Lulu Vere Childers (1870–1946), Emma Azalia Hackley (1867–1922), and Mary Cardwell Dawson (1894–1962) stand tall because of the unusual nature of their contributions.

Most impressive among institutions established by black women was the Washington Conservatory of Music and School of Expression founded in Washington, D.C., by Harriet Gibbs Marshall.[35] Marshall was the first of her race to graduate from the Oberlin Conservatory of Music as a piano major, and, after piano study in Europe, she concertized in the United States. She established a department of music (ca. 1890) at Eckstein-Norton, a small black college in Cane Spring, Kentucky, and raised money for the music building through her piano concerts and through performances of the Eckstein-Norton Choir, a group she organized and directed.[36]

Marshall's most remarkable contributions, however, were made in connection with the Washington Conservatory. Her experience at Eckstein-Norton convinced her of the need to find and train talented youth and inspired Marshall to open her school in 1903.[37] It was more widely known than other private schools owned and operated by blacks and, by offering conservatory-level instruction, attracted students mainly from Washington but also from the North, South, and Midwest. It was also the longest to survive, although not without tremendous effort on Marshall's part. In order to keep the school financially afloat, she wrote voluminously for assistance to politicians, artists, and any others whom she considered possible donors.[38] Although there was never a surplus of money on hand, the school continued to operate until 1960 with assistance from white as well as black philanthropists.[39]

From its beginning, the Washington Conservatory recruited a faculty of highly trained, and, in some cases, widely known musicians. Emma Azalia Hackley, whose later achievements as singer, conductor, and educator are discussed below, commuted from Philadelphia to teach at the conservatory during the 1903–4 academic year. Her response to the invitation to teach at the school was probably representative: "I would enjoy very much the association with you and other persons mentioned as the faculty-to-be. In a kind of faint far-off way, we have nursed a

somewhat similar idea here, but we are not so blessed with talent as is Washington."[40]

Throughout her career, Marshall was fortunate in that she was encouraged by her father, Judge Wistar Mifflin Gibbs. He contributed the building in which the school was housed, and in his letters he assured her of his support for whatever decisions she made.[41] Although she received assistance from many donors, and endorsements from prominent black musicians such as the composer Florence Price,[42] some questioned the need for the school. Henry C. King, president of Oberlin, spoke of his initial reservations, "The question . . . was whether with the musical department of Howard University, there really was any such demand for another school [in Washington]." He did finally give Marshall his endorsement, commenting, "I am glad to send you a word that I hope may be of help to you in building up your work. You certainly seem already to have developed quite an institution."[43]

In addition to the meritorious service of providing music instruction to many students, the Washington Conservatory of Music offered the Washington community a concert series that annually presented artists of national stature. As discussed earlier, the most widespread institutional support of the black concert artist came from the churches, which had since the early nineteenth century assumed the management and promotion functions of concert bureaus. Increasingly, black colleges began to sponsor musical programs, and the larger institutions such as Fisk, Hampton, and Howard sponsored annual concert series for the enjoyment of the students and the wider African-American community. At the same time, these series (whether in churches or colleges) were crucial to black performers, who in the early twentieth century, especially as they began their careers, were dependent upon this "black circuit" for performance opportunities.

An 1896 graduate of Oberlin Conservatory, Lulu Vere Childers came to Washington to join the faculty of Howard University in 1905. She was responsible for turning a small music program into, first, a Conservatory of Music (1913) and, later, into a School of Music (1918). When Howard offered its lecture-recital series in the 1920s, the young singer Marian Anderson, a friend of Childers', was among the artists. As the years passed, the series assumed an important position in Washington music affairs. Concerts by artists of national and international standing drew racially mixed audiences, an anomaly in the segregated city, and were prominently reviewed in newspapers of both black and white communities. In preparation for the 1938–39 season, Constitution Hall was sought as a larger auditorium for a recital by that same Marian Anderson, who was by now a world-renowned contralto. This request set in motion events that led to the great singer's triumphant Lincoln Memorial concert of April 1939, the result of the Daughters of the American Revolution's refusal to rent Constitution Hall for a performance by a black artist.

In view of the fact that college choir directors among women were relatively few, the achievements of Childers in this regard are particularly noteworthy. She won favorable criticism for presentations of choral masterpieces such as Handel's Messiah ,

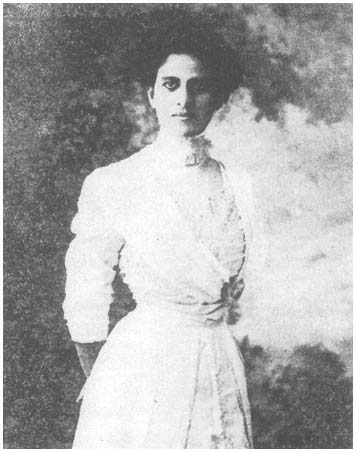

Fig. 21.

Lulu Vere Childers, choral conductor and longtime dean of the School of Music, Howard University.

Photograph possibly taken upon her receiving the honorary doctorate in music, 1942.

By permission of the Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Howard University

Archives, Howard University.

Mendelssohn's Elijah , Gabriel Pierné's The Children's Crusade , and Samuel Coleridge-Taylor's Hiawatha trilogy. Vespers services featuring the choir brought overflow audiences to the University Chapel, especially at Easter and Christmas.[44] The Department of Music at Howard University must be viewed as Childers' legacy.

Emma Azalia Hackley's wide-ranging musical activities, which included teaching voice, lecturing, and performing, seemed to be equal components in her struggle to assist young black performers. She believed that "there is a future for colored musicians. . . . If we encourage our young people generally throughout the country every five or six years some one of them will leap out of the circle of mediocrity and push his way to the front, and perhaps represent us musically as we have never been represented."[45] She, too, founded a music school, the Vocal Normal Institute of Detroit, Michigan, which existed from 1912 to 1916. After a trip to Paris to study voice, she conceived the idea of sending students to study abroad and raised money for scholarships through her own concerts and donations from patrons. She could point to several outstanding musicians whom she had helped. Clarence Cameron White (1880–1960), a violinist who became a celebrated black composer, was the first beneficiary. His $600.00 scholarship was, in Hackley's words, "a mere pittance [but still helpful] if it would score one point in favor of so many millions of people" (i.e., black Americans).[46] White used the money to study in London with Samuel Coleridge-Taylor. Foremost among recipients of the Hackley scholarship awards was another composer of national standing, R. Nathaniel Dett (1882–1943), also a pianist. The singers Cleota Collins (1893–1976) and Florence Cole Talbert and the violinists Harrison Emmanuel (dates unknown) and Kemper Harreld (1885–1971) also received assistance for study from Hackley. Carl R. Diton (1886–1962), who used his Hackley scholarship to study piano in Munich, Germany, spoke of the large number of black singers who profited from Hackley's educational activism, "She more than anyone else is responsible for the trend toward the cultivation of the Negro's natural voice and higher musical training. . . . No other Negro to my knowledge has given her time, money, and energy in this way, unselfishly and purely for the sake of the other individual."[47]

Training a young performer was not, of course, enough. Black educators must have found it galling that even their best students could find few professional opportunities. Black singers, for example, were systematically excluded from performing with white opera companies in the United States; Lillian Evanti (1890–1967) and Caterina Jarboro (1903–86), though, did sing with established companies in Europe.[48] At the turn of the century, a few singers found opportunities to perform with black traveling companies that introduced operatic finales into their shows.[49]

To counteract this state of affairs, which existed until 1955, when Marian Anderson made her belated appearance at New York's Metropolitan Opera as Ulrica in Verdi's Un ballo in maschera , black opera companies were formed. These companies, most of them episodic and short-lived, began staging opera with black casts in the 1870s.[50]

Mary Cardwell Dawson (1894–1962) accepted the challenge and established

Fig. 22.

Call for contributions (in a [1940s?] program for Aida ), National

Negro Opera Company, Inc., founded by Mary Cardwell Dawson.

Louia Vaughn Jones scrapbooks, Moorland-Spingarn Research

Center, Howard University.

the National Negro Opera Company (NNOC) in 1941. An activist teacher when she founded the Cardwell School of Music in Pittsburgh in 1927, Dawson had become aware of the desperate need of the black singer for an operatic outlet. Her company lasted for twenty-one years, mounting productions of operas and oratorios, and presenting some of the best-known black singers. One of its most successful productions was La traviata presented in 1943 in Washington, D.C., with Lillian Evanti singing the lead role. The production was heard initially by an audience of 15,000 and, to accommodate others who wished to hear it, was scheduled for a repeat performance.[51] The favorable critical review of the production must have brought well-deserved professional satisfaction to the prima donna, Lillian Evanti, and also to the far-sighted Mary Cardwell Dawson.

Fig. 23.

Maud Cuney-Hare.

By permission of Atlanta University Center, Robert W. Woodruff

Library.

Writers

After the appearance in 1878 of Music and Some Highly Musical People , the first history of African-American musicians, by the journalist and concert manager James M. Trotter,[52] no extensive historical work on the subject emerged until 1936, when Maud Cuney-Hare (1872–1936) published Negro Musicians and Their Music .[53] This volume was the culmination of Cuney-Hare's published work. She had contributed articles to The Musical Quarterly, Musical Observer, Christian Science Monitor , and Musical America ; and she wrote on current events in music and art for Crisis magazine almost from its beginning in 1910. She also toured widely as a pianist in lecture-recitals with the baritone William Richardson and assiduously collected data and materials relating to the music of black people.

Journalists

During the early twentieth century, black journalists regularly reported musical events in the black community. National black newspapers such as the New York Age, Chicago Defender, Afro-American , and Indianapolis Freeman usually carried a music column or an entertainment section in which music was often featured.[54] Writing about music took the form of simple announcements of events, extended promotions of performers and events, and, occasionally articles containing substantial critical discussion. Although the practice of music criticism was a fledgling endeavor in the black press, it was an important one, since white-controlled newspapers generally gave scant attention to music events in the black communities or, when they did, sometimes offered superficial and often supercilious comments. For the black press, informed journalistic writing about music in general and specific musical events in the black community had the educational mission of encouraging the growth of an audience for classical music.

Nora Douglas Holt (1885–1974) wrote for the Chicago Defender (1917–21; 1938–43) and later for the New York Amsterdam News (1944–64). Her thoughtful columns on music earned her a special place among pioneer African-American classical music critics and prompted the composer and music critic Virgil Thomson to sponsor her membership in the Music Critics Circle of New York in 1945. (She was its first black member.) In her desire to inform her readership about the technical aspects of classical music, to recognize talent, and to underscore the importance of the artist's contribution, she was, in effect, a music educator.[55]

Another outlet for Nora Holt's journalistic interests was the magazine Music and Poetry , which she established in January 1921. Citing the death of her husband and the resultant lack of financing as the reason for its demise "sometime in 1922," after twenty-four issues, Holt described the publication of the magazine as "a labor of great joy, [and] of course, great disappointment when it was finally given up."[56] The magazine's statement of purpose projects the themes of her newspaper columns:

This magazine is launched with the hope of interesting all who have [accepted] or anticipate accepting music as a profession, and for those who love it for the genuine happiness it brings in feeling it as an art as well as a pleasure. And next, but quite important, of encouraging and nursing creative talent—decrying sham and vulgar apishness—awarding applause and support to all sincere artists who reveal the heart of a people through their native talent. For art is greater than an individual and only that art endures which paints the soul of a race through its expression.[57]

Holt attempted to make the magazine useful to a professional readership by including guest articles by white and black writers on technique and pedagogy. A feature that must surely have attracted readers was the presentation of a complete composition for voice, violin, or piano solo in each issue; the first ten issues included two of Holt's own compositions.

Music and Poetry was the second magazine published by a black American that

Fig. 24.

Nora Holt, composer, critic, and founder of the National

Association of Negro Musicians.

Rose McClendon Collection, Yale Collection of American Literature,

Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscripts Library, Yale University.

was devoted to music. Thirty-five years earlier, in 1886, another black woman, Amelia L. Tilghman, had produced the first issue of the Musical Messenger . Announcing it as "the first attempt at musical journalism among the colored people in this country," Tilghman expressed the belief that her audience would "feel a deep interest in every new step that has for its object the further advancement and progress of our race in all the intellectual avenues of life."[58]

In 1919, Holt was instrumental in the founding of the National Association of Negro Musicians (NANM), a unique organization that is still in existence. Its aim of "furthering and coordinating the musical forces of the Negro race for the promotion of economic, educational and fraternal betterment" was consonant with Holt's purpose as announced in Music and Poetry .[59] As NANM's first vice president, Holt publicized the organization in each issue of her magazine, announcing activities and meetings of branches. Women activists in music of the 1920s, 1930s, and 1940s were well represented in the NANM, both in membership and in positions of leadership. Four women were among those who served as presidents from its founding in 1919 to 1942.[60]

Preservers of the Heritage

Among community leaders, educators, and writers, there were those who understood that the precious folk-music heritage of the African-American should be preserved. Beginning in the late nineteenth century with the publication of collections of spirituals, the process of preservation gained impetus through the performance and recognition of the Fisk Jubilee Singers.[61] Further impetus was provided by organizations such as the Society for the Collection of Negro Folklore, founded in 1890 by blacks in Boston. One of the founders was a black woman, Florida Ruffin Ridley (dates unknown).[62]

The New Negro Movement of the 1920s and early 1930s, or, as it was later called, the Harlem Renaissance,[63] infused energy into the thrust to preserve the black heritage in music. Some theorists valued the folk genres in their original state and wished to preserve, in a form as close to the original as possible, what they saw as genuine, albeit vanishing, cultural expressions. Others, devoted to the concept of concert music in the classical sense, promoted the trained composer and valued folk music for its use in concert pieces written in European style. Harriet Gibbs Marshall established a National Center for Negro Music, which she envisioned as a repository for both folk music and the published compositions of black composers.[64] Maud Cuney-Hare and Camille Nickerson collected and made arrangements of Creole folk songs[65] and used the recital to make them known. Nickerson dramatized her concerts by adopting the sobriquet "Louisiana Lady" and performing in Creole costume as she toured in the United States and France.[66]

In the movement to preserve the black heritage in music, Emma Azalia Hackley again looms large. Pursuing her purpose of stimulating interest in the Negro spiritual with characteristic vigor, she lectured and conducted community cho-

In the notes to this essay, the Moorland-Spingarn Research Center at Howard University is referred to as MSRC, and the National Negro Opera Company as NNOC.

ruses from 1910 to 1921, the year before her death, in the United States and other countries, including Japan (1920). "Wherever she has been the results have been surprising, not only in arousing interest among the colored people, but also among the white population," a writer for Musical America said with reference to a program in Montgomery, Alabama. Citing features of a typical Hackley Folk Song Festival, the article notes that the aggregation of around 200 mixed voices aroused tremendous enthusiasm in the audience. Hackley's dedicated activity caused her to be known among black writers on music as "Our National Voice Teacher."[67]

The first half of the twentieth century was a period of growth for the black classical musician and, at the beginning, outlets for musical activity were to be found mainly within the black community. The careers of black women activists who worked to develop interest in music of the cultivated tradition among African-Americans reflect a common struggle against racism and sexism and also demonstrate the impossibility of separating personal ambition from the desire to enhance the status of black Americans. Whether working as individuals or as groups, on a local or national scale, black women activists sought and found ways to expand the "sphere" not only of black women, but also that of blacks generally, in music, until it was indeed "just as large as [they could] make it."