Introduction

Greater complexity is generally ascribed to the six movements constituting Part II of The Rite . In the current view, this has principally to do with a more intimately paced relationship among the three transpositions of the octatonic collection. Contexts of transpositional purity (confined, that is, to a single collection) are of course still to be found. Shown in Example 61 in Chapter 6, the blocks at nos. 132 and 134 in the "Ritual Action of the Ancestors," where Collection I's (C

Example 69:

"Glorification of the Chosen One"

It is as though the composer, having exposed an explicit octatonic hand in Part I, felt the necessity of venturing a bit further in Part II, upping the octatonic coherence stakes, as it were.

These implications are apparent in the very first measures of Part II's Introduction. Reproduced in Example 70, two minor triads, (E

Example 70:

Introduction

form to the octatonically conceived (0, 3, 6, 9) arrangement. It is, rather, a 1-1-1 relationship, which means that each triad will refer to a different octatonic collection. These, too, are circumstances that do not readily lend themselves to an octatonic interpretation.

Yet when the configuration at no. 79 is heard and understood in relation to what follows, there is no mistaking its octatonic purpose. The oscillating (E

In the

The scheme perseveres at no. 79 + 5 (again, see Example 71). The (E

Example 71:

Introduction

are in turn followed by the Collection I triads at no. 82 + 4. And, as earlier at no. 79 + 5, the bass line reinforces these Collection III–Collection I shifts with dominant sevenths on E and G (for Collection I) and on F

A different version of the chordal progression at no. 82 appears later, at no. 161 in the "Sacrificial Dance." From what may be gathered from two separate entries on pages 85 and 104 of the sketchbook,[3] the progression was originally intended for the concluding "sacrifice" alone. Indeed, as with the "Augurs of Spring" chord (see Example 59 in Chapter 6), this idea may have been conceived in advance of the

[3] Being virtually identical, these two sketches fail to reflect the differences between the two final versions of the Introduction and the "Sacrificial Dance."

Example 72:

Introduction

sketchbook. Transcribed in Examples 73a and 73b are two early sketches from a separate notebook,[4] which may be compared to the sketchbook's version of the progression on page 104 (Example 73c), and then to the two final versions as found

[4] The two early sketches appear in Vera Stravinsky and Robert Craft, Stravinsky in Pictures and Documents (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1978), p. 599, and are derived from the small notebook mentioned in Chapter 2 as dating from 1912 to 1918. Craft refers to it as the "Klychkov notebook," since it contains an unfinished setting of a poem by the symbolist poet Sergei Klychkov. He also dates the sketches "July, 1911," but there is in fact no evidence to suggest that they were not composed much later, during the actual composition of the "Sacrificial Dance." What seems clear is that both were intended for The Rite and that they predate the two notations on pages 85 and 104 of the sketchbook. They are reproduced in Figure 4.

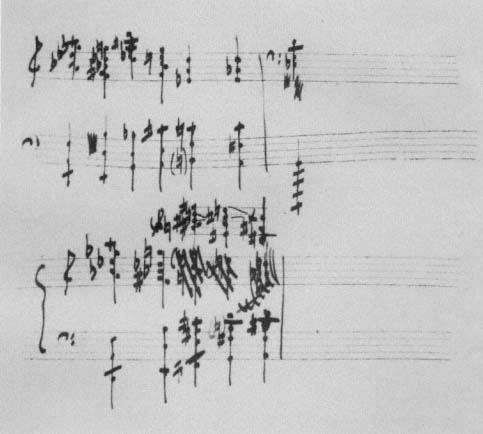

Figure 4:

Early sketches of the chordal progression at nos. 82 and 161 in the Introduction and "Sacrificial

Dance." These are taken from the separate notebook dating from 1912 to 1918.

Courtesy of the Paul Sacher Foundation.

at no. 82 in the Introduction (Example 72) and at no. 161 in the "Sacrificial Dance" (Example 73d).[5] Notice that the contrary motion of the diatonic outer parts was not initially part of the conception, and that only three chords in the two early sketches in Examples 73a and 73b survive in the two final versions of the Introduction and the "Sacrificial Dance."

Most remarkable, however, is the manner in which the progression was re-

Example 73

composed with a view toward the referential conditions as surveyed already apropos of the opening measures of the Introduction. In his own brief survey of these early sketches, Robert Craft has called attention to the "evolution in harmonic content" and to the manner in which the composer "gravitated, instinctively and unconsciously, toward The Rite 's fundamental combinations."[6] This is clear from an

[6] V. Stravinsky and Craft, Stravinsky in Pictures and Documents , p. 599. In Allen Forte, The Harmonic Organization of "The Rite of Spring" (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1978), p. 199, the author pointssimilarly to Stravinsky's "predilection" for this progression, noting that the two final versions in The Rite "contain many, if not all, of the basic harmonies of the work."

octatonic standpoint. For although five of the seven chords of the sketchbook version are octatonic, these refer to Collections I, II, and III. Following the initial (D F A) triad in the recomposed version for the Introduction, however (see Example 72), the succession is committed solely to Collections I and III, with each

Of course, the Khorovod tune of the Introduction, for which the sustained A and the (D F A) triad at no. 79 are a preparation, has been overlooked. And the Collection II implications of these components are occasionally evident. Example 74 shows one of the several variants of this tune. Introduced at no. 84, a Collection II chord alternates with others implying Collections III and I. Most important, however, is this tune's B

Thus, as shown on the left side in Example 75, the upper part of the initial configuration consists of a B

Example 74:

Introduction

Example 75:

Introduction

I to Collection III, a shift duly confirmed by the entrance of the reiterating 0–5, 11 verticals at no. 86 + 3.

Shown in Example 76, these verticals also derive in straightforward fashion from the initial configuration at no. 79. Embedded in the configuration, below the B

Example 76:

Introduction

E. The second trumpet's (B

Still, the harmonic distinction between Collections I and III, carefully paced and patterned in the preparatory measures at no. 86, is eventually obscured at no. 87 + 1. And this is principally a rhythmic issue. For as is frequently the case with the climactic settings of The Rite , the construction at nos. 87–89 conforms in general outline to the second of the two rhythmic types as detailed in Chapter 4. The fragments, lines or parts, fixed registrally and instrumentally in repetition, are brought together in a final, tutti summation; they repeat according to periods or cycles that vary independently of one another, and hence effect a vertical or harmonic coincidence that is constantly changing. And given the inevitable overlapping in period-duration, the initial harmonic synchronization as introduced at no. 86 + 3 will not hold, and the fragments implicating Collection I will fuse with those implicating Collection III. At no. 87 + 2, Collection III's E

A condensed layout of the scheme appears in Example 78. The first of the three

Example 77

layers shows the successive repeats of the (C E G) triad in the flutes, the second layer those of the clarinet-horn fragments, and the third layer those of the reiterating 0–5, 11 verticals in the strings. In sum, the overlapping in period duration, together with the gradual harmonic fusion between Collections I and III, promote a truly remarkable richness in sound at nos. 87–89, in keeping with the climactic character of the passage and with the specifics of the collectional shifts as introduced earlier in this movement.

Example 78:

Introduction