7—

Part II: Pitch Structure

Introduction

Greater complexity is generally ascribed to the six movements constituting Part II of The Rite . In the current view, this has principally to do with a more intimately paced relationship among the three transpositions of the octatonic collection. Contexts of transpositional purity (confined, that is, to a single collection) are of course still to be found. Shown in Example 61 in Chapter 6, the blocks at nos. 132 and 134 in the "Ritual Action of the Ancestors," where Collection I's (C

Example 69:

"Glorification of the Chosen One"

It is as though the composer, having exposed an explicit octatonic hand in Part I, felt the necessity of venturing a bit further in Part II, upping the octatonic coherence stakes, as it were.

These implications are apparent in the very first measures of Part II's Introduction. Reproduced in Example 70, two minor triads, (E

Example 70:

Introduction

form to the octatonically conceived (0, 3, 6, 9) arrangement. It is, rather, a 1-1-1 relationship, which means that each triad will refer to a different octatonic collection. These, too, are circumstances that do not readily lend themselves to an octatonic interpretation.

Yet when the configuration at no. 79 is heard and understood in relation to what follows, there is no mistaking its octatonic purpose. The oscillating (E

In the

The scheme perseveres at no. 79 + 5 (again, see Example 71). The (E

Example 71:

Introduction

are in turn followed by the Collection I triads at no. 82 + 4. And, as earlier at no. 79 + 5, the bass line reinforces these Collection III–Collection I shifts with dominant sevenths on E and G (for Collection I) and on F

A different version of the chordal progression at no. 82 appears later, at no. 161 in the "Sacrificial Dance." From what may be gathered from two separate entries on pages 85 and 104 of the sketchbook,[3] the progression was originally intended for the concluding "sacrifice" alone. Indeed, as with the "Augurs of Spring" chord (see Example 59 in Chapter 6), this idea may have been conceived in advance of the

[3] Being virtually identical, these two sketches fail to reflect the differences between the two final versions of the Introduction and the "Sacrificial Dance."

Example 72:

Introduction

sketchbook. Transcribed in Examples 73a and 73b are two early sketches from a separate notebook,[4] which may be compared to the sketchbook's version of the progression on page 104 (Example 73c), and then to the two final versions as found

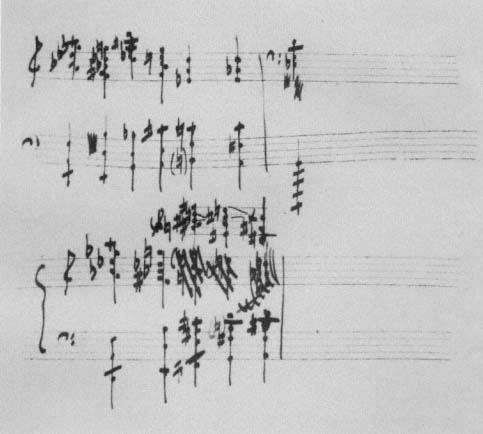

[4] The two early sketches appear in Vera Stravinsky and Robert Craft, Stravinsky in Pictures and Documents (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1978), p. 599, and are derived from the small notebook mentioned in Chapter 2 as dating from 1912 to 1918. Craft refers to it as the "Klychkov notebook," since it contains an unfinished setting of a poem by the symbolist poet Sergei Klychkov. He also dates the sketches "July, 1911," but there is in fact no evidence to suggest that they were not composed much later, during the actual composition of the "Sacrificial Dance." What seems clear is that both were intended for The Rite and that they predate the two notations on pages 85 and 104 of the sketchbook. They are reproduced in Figure 4.

Figure 4:

Early sketches of the chordal progression at nos. 82 and 161 in the Introduction and "Sacrificial

Dance." These are taken from the separate notebook dating from 1912 to 1918.

Courtesy of the Paul Sacher Foundation.

at no. 82 in the Introduction (Example 72) and at no. 161 in the "Sacrificial Dance" (Example 73d).[5] Notice that the contrary motion of the diatonic outer parts was not initially part of the conception, and that only three chords in the two early sketches in Examples 73a and 73b survive in the two final versions of the Introduction and the "Sacrificial Dance."

Most remarkable, however, is the manner in which the progression was re-

Example 73

composed with a view toward the referential conditions as surveyed already apropos of the opening measures of the Introduction. In his own brief survey of these early sketches, Robert Craft has called attention to the "evolution in harmonic content" and to the manner in which the composer "gravitated, instinctively and unconsciously, toward The Rite 's fundamental combinations."[6] This is clear from an

[6] V. Stravinsky and Craft, Stravinsky in Pictures and Documents , p. 599. In Allen Forte, The Harmonic Organization of "The Rite of Spring" (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1978), p. 199, the author pointssimilarly to Stravinsky's "predilection" for this progression, noting that the two final versions in The Rite "contain many, if not all, of the basic harmonies of the work."

octatonic standpoint. For although five of the seven chords of the sketchbook version are octatonic, these refer to Collections I, II, and III. Following the initial (D F A) triad in the recomposed version for the Introduction, however (see Example 72), the succession is committed solely to Collections I and III, with each

Of course, the Khorovod tune of the Introduction, for which the sustained A and the (D F A) triad at no. 79 are a preparation, has been overlooked. And the Collection II implications of these components are occasionally evident. Example 74 shows one of the several variants of this tune. Introduced at no. 84, a Collection II chord alternates with others implying Collections III and I. Most important, however, is this tune's B

Thus, as shown on the left side in Example 75, the upper part of the initial configuration consists of a B

Example 74:

Introduction

Example 75:

Introduction

I to Collection III, a shift duly confirmed by the entrance of the reiterating 0–5, 11 verticals at no. 86 + 3.

Shown in Example 76, these verticals also derive in straightforward fashion from the initial configuration at no. 79. Embedded in the configuration, below the B

Example 76:

Introduction

E. The second trumpet's (B

Still, the harmonic distinction between Collections I and III, carefully paced and patterned in the preparatory measures at no. 86, is eventually obscured at no. 87 + 1. And this is principally a rhythmic issue. For as is frequently the case with the climactic settings of The Rite , the construction at nos. 87–89 conforms in general outline to the second of the two rhythmic types as detailed in Chapter 4. The fragments, lines or parts, fixed registrally and instrumentally in repetition, are brought together in a final, tutti summation; they repeat according to periods or cycles that vary independently of one another, and hence effect a vertical or harmonic coincidence that is constantly changing. And given the inevitable overlapping in period-duration, the initial harmonic synchronization as introduced at no. 86 + 3 will not hold, and the fragments implicating Collection I will fuse with those implicating Collection III. At no. 87 + 2, Collection III's E

A condensed layout of the scheme appears in Example 78. The first of the three

Example 77

layers shows the successive repeats of the (C E G) triad in the flutes, the second layer those of the clarinet-horn fragments, and the third layer those of the reiterating 0–5, 11 verticals in the strings. In sum, the overlapping in period duration, together with the gradual harmonic fusion between Collections I and III, promote a truly remarkable richness in sound at nos. 87–89, in keeping with the climactic character of the passage and with the specifics of the collectional shifts as introduced earlier in this movement.

Example 78:

Introduction

"Sacrificial Dance"

In stunning contrast to the separate, climactic block of the Introduction at nos. 87–89, the opening section of the "Sacrificial Dance" conforms to the first of the two rhythmic types outlined in Chapter 4. Labeled A, B, and C in Example 79, three blocks are placed in rapid juxtaposition; within each of these blocks the lines or parts repeat according to the same rhythmic periods and are hence synchronized unvaryingly in vertical coincidence; and the invention has principally to do with the reordering, expansion, or contraction of these blocks and their motivic subdivisions upon successive restatements. Earlier, in Example 36 in Chapter 3, attention

Example 79:

"Sacrificial Dance"

Example 79

(continued)

was drawn to the two motives of Block B and to the upbeat-downbeat contradictions to which subsequent repeats of these motives were subjected in relation to a background

No less apparent in Example 79, however, is the adherence at the outset of the "Sacrificial Dance" to The Rite 's by now standard pitch formulae. There is, first, the punctuating dominant seventh of Block A, here (D C A F

Indeed, Block C is in this respect favorably understood as a continuation of the collectional implications of Block A. Shown in Example 80, Blocks A and C are composed of four relatively static layers of material: (1) the (E

Example 80:

"Sacrificial Dance"

ensures (E

What thus emerges in Blocks A and C (Example 80) is the superimposition of the fixed (E

Subsequent transpositions of the opening section of the "Sacrificial Dance" are traced in Example 81. Earlier, in Example 65, the origin of the first of these transpositions at no. 167, down a half step from (D C A F

Example 81:

"Sacrificial Dance"

those pitches in the C-B

But to return for a moment to the opening statement of Block A. Even the non-octatonic pitches in this initial stretch, the non—Collection II D

Example 82:

"Sacrificial Dance" (transpositions)

Example 83:

"Sacrificial Dance"

Ultimately of greater consequence, however, are the two upper and lower 2s or whole steps of this (0 1 2 3) tetrachord: that is, in Block A, D-C and E

of the "Sacrificial Dance" make reference.[7] Thus, further along, at no. 158, shown in Example 83, the two oscillating 0–5, 11 verticals in the strings, D-A, E

The Pitch-Class Set

Still, questions may linger about the completeness of the octatonic record in Part II, and in particular about the rapid collectional shifts and consequent "outside" pitch elements. Could the approach at this point benefit from, say, certain of Allen Forte's set-theoretic formulations? The answer here seems to be yes, but only up to a rather limited point. Readers familiar with Forte's analysis of Stravinsky's early works will have noted a number of correspondences. Forte frequently invokes the octatonic collection, the "superset" 8–28, and in connection with a passage from Zvezdoliki [The King of the Stars ] (1911–12) cites it as "one of Stravinsky's hallmarks."[8] In Forte's The Harmonic Organization of "The Rite of Spring," the (0 2 3 5) tetrachord, pitch-class set 4–10, is encountered throughout, while its (0 2 5/0 3 5) incomplete form, 3–7, is identified as "a kind of motto trichord."[9] In fact, most of the prominent sets in Forte's analysis are subsets of the octatonic collection. Of his two hundred and twenty pitch-class sets (sets of from three to nine elements, reduced to a "best normal order" by means of transposition or inversion followed by transposition), thirty-four are octatonic: seven from a possible twelve three-element sets, thirteen from the twenty-nine four-element sets, seven from thirty-eight five-element sets, six from fifty hexachords, and one from the thirty-eight seven-element sets, 7–31. These are easily spotted since the pitch numbering of these thirty-four "prime forms" will correspond to that either of the 1–2 half step-whole step ordering, (0 1 3 4 6 7 9 10 (0)), or the reverse 2-1 whole step-half step ordering, (0 2 3 5 6 8 9 11 (0)).

Beyond this point the two paths diverge as different objectives are brought into play. In particular, the segmentation, what Forte interprets as cohesive units in The

[8] Allen Forte, The Structure of Atonal Music (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1973), p. 118.

[9] Forte, The Harmonic Organization , p. 36.

Rite , differs markedly from that proposed here. Reference is occasionally made to the dominant seventh, 4–27, but the triad, 3–11, is ignored altogether since, as Forte notes, trichords "are easily identifiable components of larger sets."[10] In the view expressed here, however, the triad—not just the three-element trichord, but the triad —assumes, even under conditions of superimposition, a registral, instrumental, and notational reality—and to an extent that, on a strictly observational basis, many sections of The Rite seem more overtly triadic than many pieces of the later nineteenth-century tonal tradition (pieces on behalf of which the triad is nonetheless routinely invoked as a fundamental unit of musical structure).

Moreover, an emphasis is here placed on disposition, on the fixed, registral identities of recurring tetrachords, 0–5/6, 11 vertical spans, triads, and dominant sevenths. These matters are often obscured when, for purposes of comparison, of gauging the relatedness of sets and complexes of sets, such groupings are regularly reduced to their "prime forms" (by means, as indicated, of transposition or inversion followed by transposition.) Thus, a prime determinancy in Part II's Introduction at nos. 79–84 is not the triad tout court , 3–11, nor the tight disposition of the triad, but its persistent (0 3 7) minor articulation. But since the major and minor triads are inversionally equivalent and reduce to the single pitch-class set 3–11, the distinction is likely to be obscured. A similar case can be made for the dominant-seventh chord, whose special content and disposition are of such marked consequence to an octatonic reading of Part I and of the "Sacrificial Dance" in Part II. This determinacy is also obscured when it is subsumed under the broader implications of the set 4–27 and its (0, 2, 5, 8) "prime-form" numbering. (The strict inversion of this form yields The Rite 's familiar disposition; the "prime form" itself is not a dominant-seventh chord.)

Similarly, the two interval orderings of the octatonic collection, along with the three transpositions of distinguishable content, reduce to the single set 8–28. But the question of an octatonic presence in The Rite has not to do merely with the octatonic collection (that is to say, 8–28 tout court ) but equally with an octatonic collection. Contexts derive their octatonic character, their symmetrical cohesion, by virtue of their confinement to a single transpositional level for periods of significant duration. And this, too, points to a hearing and understanding of determinacy having as much to do with pitch and pitch-class identity as with interval-class identity.

This is not to suggest that these issues are ignored by Forte. Frequent reference is made to invariance in pitch-class content between transpositions or transformations of a given set, and then to the Rp relation, which has to do with pitch-class invariance among non-equivalent sets having the same number of elements. But here, too, Forte's conclusions are apt to vary from those reached from a predominantly octatonic or octatonic-diatonic perspective. Thus, Example 84 shows twelve single and "composite" sets invoked by Forte to identify the verticals and

[10] Ibid.

Example 84

linear successions of Block C at no. 144 in the "Sacrificial Dance" and its subsequent near-repeat at no. 148.[11] (Although in ascending "normal order," the pitch numbering of these sets has not been reduced to that of the "prime forms." Note that 0=C.)[12] Only sets 5–10 and 6-Z23 are octatonic; the others are not subsets of the octatonic collection 8–28. But the fact that all ten non-octatonic sets miss the

[11] Forte, The Structure of Atonal Music , pp. 147–48. Forte uses the 1943 revision of the "Sacrificial Dance" for his analysis. The orchestration and barring of this passage are changed, but the chords themselves remain unaltered.

[12] With O = C (and with the sets not reduced to their "prime forms"), a (0 2 3 5 6 8 9 11) numbering will always—as is shown in Example 84—imply Collection II. A (0 1 3 4 6 7 9 10) numbering under these conditions will imply Collection III, while the numbering for Collection I (which lacks the C) will conform to neither of the two octatonic pitch-numberings.

octatonic order by a single step (at pitch number 10 here), or, more importantly, that all sets, excluding the B

Incompatibility is not really the issue here. The notion of the pitch-class set and its attendant formulations ("similarity," "complementation," and so forth) can in no way be construed as "incompatible" with a more determined octatonic or octatonic-diatonic reading. At issue, rather, is the referential character of the octatonic and diatonic sets, the extent of their hegemony in The Rite and hence, ultimately, the degree of abstraction deemed necessary or desirable in formulating rules of equivalence and association that can account for the coherence or consistency of the harmonic and melodic materials.

Inevitably, a theorist's choices in this regard are to some extent guided by his preoccupations with other literatures and traditions. But this does not mean that the set-theoretic approach is awkwardly "neutral" or without an historical foundation. The Rite is unquestionably non-tonal, and frequently exhibits, as Forte has

[14] Forte, The Structure of Atonal Music , p. 154.

[15] Ibid., p. 159.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Ibid., p. 166.

claimed, the kinds of harmonic structures prevalent in the "atonal" music of Schoenberg, Berg, and Webern.[18] Nonetheless, as an attempt to cope with a large number of seemingly intractable works, pitch-class set analysis represents a retreat to more lenient and broadly defined terms of relatedness and association. The question, then, is whether, for its proper definition, the logic of The Rite requires the greater generality afforded by this retreat or whether, by means of an octatonic-diatonic determination, the piece remains susceptible to the more determinate rulings of a more familiar mode of reckoning, one characterized by scales, scalar orderings and numberings, triads, pitch-class priorities, and the like. The present discourse has of course opted for the second of these alternatives. Yet the underlying assumptions of set theory have by no means been ignored. While frequently in disagreement with the meaning and significance of many of Forte's set-theoretic conclusions, the present perspective may nonetheless be placed in sharper focus by a careful consideration of those results.

Conclusions

As the last of the three big "Russian" ballets, The Rite exhibits features in rhythmic and pitch structure that were to remain characteristic of Stravinsky for the greater part of his composing career. The two types of rhythmic construction outlined in Chapters 3 and 4 are as conspicuously a part of pieces such as the Symphony of Psalms (1930) and the Variations (1964) as they are of The Rite . And while Renard, Les Noces , and Histoire du soldat mark a sudden preference for smaller, chamber-like ensembles, pitch relations in these works can be identified closely with those of The Rite . Even neoclassicism, for so long defined in terms of a sharp stylistic break with earlier trends, can often revealingly be heard and understood in relation to prior inclinations and concerns as detailed in these pages.

Of course, the octatonic articulation in neoclassical works often differs from that of The Rite and other works of the "Russian" category. Instead of the (0 2 3 5) tetrachord, an (0 1 3 4) tetrachord may frequently be inferred as a cohesive linear

[18] Tonality is here viewed in its restricted and historically oriented sense as a hierarchical system of pitch relations based referentially on the major-scale ordering of the diatonic set and encompassing an intricate yet fairly distinct set of harmonic and contrapuntal procedures commonly referred to as tonal functionality or "triadic tonality." The by now classic formulation of this view is given in Arthur Berger, "Problems of Pitch Organization in Stravinsky," in Benjamin Boretz and Edward T. Cone, eds., Perspectives on Schoenberg and Stravinsky (New York: Norton, 1972), p. 123. Berger writes: "Tonality . . . is defined by those functional relations postulated by the structure of the major scale. A consequence of the fulfillment of such functional relations is, directly or indirectly, the assertion of the priority of one pitch class over the others within a given context—it being understood that context may be interpreted either locally or with respect to the totality, so that a hierarchy is thus established, determined in each case by what is taken as the context in terms of which priority is assessed. It is important to bear in mind, however, that there are other means besides functional ones for asserting pitch-class priority; from which it follows that pitch-class priority per se: (1) is not a sufficient condition of that music which is tonal, and (2) is compatible with music that is not tonally functional."

Example 85

grouping. Indeed, in the Symphony of Psalms it surfaces as a kind of "basic cell" in the first and second movements, as Stravinsky himself noted in one of his "conversations" with Robert Craft.[19] Complementing the (0 1 3 4) tetrachord are the (0 3 4/3 4 7/3 6 7) minor-major third units and, most conspicuously, the triads and dominant sevenths as cited in Chapters 5, 6, and 7 (but in neoclassical works with an overall approach in disposition more varied than that encountered in The Rite or in "Russian" pieces generally). The typical neoclassical format is summarized in Example 85: an (0, 3, 6, 9) symmetrically defined partitioning of Collection I in terms of this collection's (0 1 3 4) tetrachords, (0 3 4/3 4 7/3 6 7) minor-major thirds, triads, and dominant sevenths at E, G, B

Such changes naturally coincide with changes in the diatonic articulation. In place of the D-scale ordering so prevalent in "Russian" contexts such as The Rite , the major scale is typical of neoclassicism, although both the E-scale and the A-scale may also at times be inferred. This major-scale reference is implied not only by the surface gesture and conventions of baroque and classical literature, but occasionally, and in however peripheral a manner, by certain tonally functional rela-

[19] Igor Stravinsky and Robert Craft, Dialogues (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1983), p. 77.

tions as well. What is often typical of the relations Stravinsky employed in these contexts can in turn be traced to an interacting partitioning of the octatonic collection as shown in Example 85; that is to say, to the manner in which this partitioning interacts with the gestures, conventions, and harmonic routines of the baroque and classical major-scale tradition.

These are obviously matters of considerable complexity, and have in fact been dealt with elsewhere in detail.[20] Consider, however, the tonic-dominant relationship insofar as this may here and there be felt as assuming a credible presence. The first movement of the Symphony of Psalms is a piece wherein octatonic blocks, accountable to Collection I with a background partitioning in terms of (E, G, B

Hence the neoclassical perspective becomes conditioned by considerations of The Rite and other works of the "Russian" period. And the attraction of this approach is that a distinctive musical presence is in some measure brought to bear. For while individual pieces naturally yield their own rationales, these are most advantageously approached as parts of a greater whole, of a wider listening experience. And since, for most enthusiasts, the sense of a musical identity or distinctiveness on the part of this composer is unmistakable, speculation along these lines is likely to prove tempting for many years to come.

[20] See Pieter C. van den Toorn, The Music of Igor Stravinsky (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1983).