Problems of Medical Quackery

Along with these exciting breakthroughs in medical technology, a very different side of the industry flourished. The popularity of fraudulent devices, and concern about the consequences of that fraud, tainted public perception of the industry. Many people associated medical devices with quack products.[25]

The term quack dates to the sixteenth century and is an abbreviation for quacksalver. The term refers to a charlatan who brags or "quacks" about the curative or "salving" powers of the product without knowing anything about medical care. From the Washington Post, 8 July 1985, 6.

When medical science offers no hope of treatment or cure, people have traditionally turned to charms and fetishes for help.[26]

Warren E. Schaller and Charles R. Carroll, Health Quackery and the Consumer (Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders, 1976), 228. This volume contains many descriptions of a variety of fraudulent devices. It makes for amusing reading, but deceptive activities left a lasting legacy on the medical device industry.

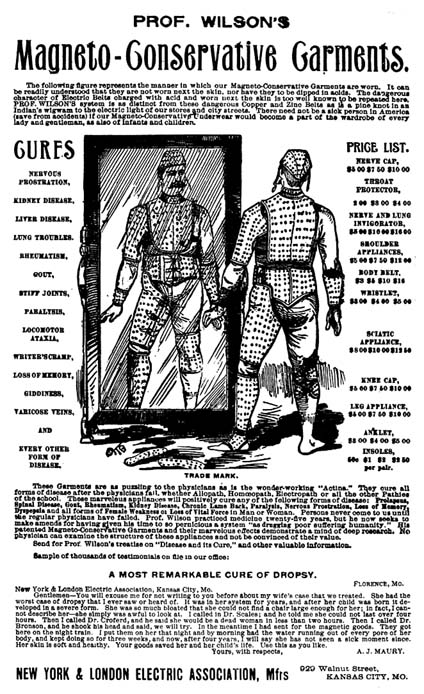

The desperate search for cures was a major factor in the success of all forms of health fraud, including tonics, drugs, potions, and quack devices. Indeed, it is estimated that the public spent $80 million in 1906 on patent medicines of all kinds. The proliferation of quack devices helped to generate subsequent government intervention to protect the public.Innovative developments in scientific fields, such as electromagnetism and electricity, were often applied to lend credence to these health frauds (see figure 5). At the turn of the century, Dr. Hercules Sanché developed his Electropoise machine to aid in the "spontaneous cure of disease."[27]

James H. Young, Medical Messiahs (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1967), 243.

This device, consisting of a sealed metal cylinder attached to an uninsulated flexible cord that, in turn, attached to the wrist or ankle, supplied, according to the inventor, "the needed amount of electric force to the system and by its thermal action places the body in a condition to absorb oxygen through the lungs and pores."[28]Ibid.

The Oxydonor was a subsequent "improvement" that added a stick of

Figure 5. A quack device.

Source: The Bakken Archives.

carbon to the sealed, and incidentally hollow and empty, cylinder and "cured all forms of disease." The success of the Oxydonor spawned a whole cadre of imitations. There was a death knell for these "pipe and wire" therapies when the inventor of the Oxypathor was convicted of mail fraud. Evidence collected at the trial revealed that the company had sold 45,451 Oxypathors at $35 each in 1914. Considering that as late as 1940 per capita spending on health was only $29.62, the consequences of wasted expenditures seem serious.

Another fraud was based on the new field of radio communications. Dr. Albert Abrams of San Francisco introduced his "Radionics" system, which was based on the pseudomedical theory that electrons are the basic biological unit and all disease stems from a "disharmony of electronic oscillation." Dr. Abrams's diagnoses were made by placing dried blood specimens into the Radioscope. Operated with the patient facing west in a dim light, the device purported not only to diagnose illness but also to tell one's religious preference, sex, and race. At the height of its use, over 3,500 practitioners rented the device from Abrams for $200 down and $5 a month.[29]

Schaller and Carroll, Health Quackery, 226.

One of Abrams's followers was Ruth Drown. She marketed the Drown Radio Therapeutic Instrument, which she claimed could prevent and cure cancer, cirrhosis, heart trouble, back pain, abscesses, and constipation. The device used a drop of blood from a patient, through which Drown claimed she could "tune in" on diseased organs and restore them to health. With two drops she could treat any patient by remote control. A larger version of her instrument was claimed to diagnose as well as to treat disease. Thousands of Californians patronized her establishment.[30]

Drown v. U.S., 198 F.2d 999 (1952). Drown was prosecuted for grand larceny and died while awaiting trial. See Joseph Cramp, ed., Nostrums and Quackery and Pseudo-Medicine, vols. 1-3 (Chicago: Press of the American Medical Association).

Unfortunately for legitimate medical device producers, the prevalence of device quackery tainted the public's perception of the industry. Indeed, initial state and federal efforts to regulate the industry were in response to problems of fraud. Device fraud continues, especially for diseases like arthritis and cancer and for weight control.[31]

Concern about fraudulent drugs and devices surfaces periodically. Congress has held hearings investigating health frauds, particularly frauds against the elderly. See, for example, House Select Committee on Aging, Frauds Against the Elderly: Health Quackery, 96th Cong., 2d sess., no. 96-251 (Washington, D.C.: GPO, 1980). In 1984, the FDA devoted only about one-half of 1 percent of its budget to fighting quack products. Under pressure from the outside, it set up a fraud branch in 1985 to process enforcement actions. See Don Colburn, "Quackery: Medical Fraud Is Proliferating and the FDA Can't Seem to Stop It," Washington Post National Weekly Edition, 8 July 1985, 6. For a description of past and present device quackery, see Stephen Barrett and Gilda Knight, eds., The Health Robbers: How to Protect Your Money and Your Life (Philadelphia: George F. Stickley, 1976).

Fraud in the industry can be seen as a market failure that subsequent government prescriptions sought to correct.