Syndicalists, Socialists, and Electoral Politics

Syndicalists had always manifested a certain rhetorical hostility to electoral politics and legislative solutions to workers' problems, but that hostility increased during this period of labor unrest in the Midi. Many syndicalists remained hesitant about if not hostile to collaboration with socialists. As one delegate to the founding congress of the FTAM (in 1903) pointed out, "When [a socialist employer pays] his workers . . . two francs a day and withdraws their wine allocation from the beginning of August, he deserves to be treated as a capitalist and as the enemy of the worker."[71] In the eyes of another syndicalist, socialists were no more trustworthy than radicals or Bonapartists: "If the Empire shot down workers at La Ricamarie, Constans did the same at Fourmies, and Millerand did the same at Chalons . . . were we to have our 'friends' in power, or those who call themselves our friends, it would be the same. . . . How can we be sure that even a socialist government would satisfy our demands?"[72]

Syndicalists' reservations about politics emerged from their

practical efforts to establish their independence from political parties. The POF in particular made no secret of its disregard for syndicalist autonomy or syndicalist use of the strike. Ernest Ferroul, for instance, more than once defended the Guesdist position concerning strikes, arguing that the conquest of political power was far more important than the strike to the reconstruction of society; the strike was merely a secondary tool and could not, in and of itself, bring about the revolutionary expropriation of capital.[73] Southern syndicalists knew that Guesdists discouraged the use of strikes elsewhere in France, and it was in this context that their rhetorical distancing from political parties occurred—even after the SFIO supported syndicalist autonomy and in principle accepted the revolutionary value of the general strike. Some workers' hostility to electoral politics resulted also from their own experience of being pressured by employers or estate managers. Not everyone shared these views, however, as Paul Ader implied when he deplored workers' failure to disengage themselves from "democratic prejudices" and their continued attachment to "diverses manifestations éléctorales."[74] In fact Simon Castan, head of the Syndicat des travailleurs de la terre de Narbonne, argued that "it would be madness to think that the proletariat must detach itself from political struggles. Economic action cannot succeed without political action."[75]

Socialist unification in 1905, combined with awareness of the government's willingness to use force against workers, compelled syndicalists throughout France to debate cooperation with Socialists prior to the CGT's 1906 congress at Amiens. Meeting in Arles that summer, the FTAM defeated the proposal of the Fédération du textile for establishing ties between the CGT and the newly unified Socialist party (Section française de l'Internationale ouvrière, or SFIO)—"so that when circumstances warrant it, our exploiters and our governments will find themselves face to face with a united working class."[76] In a heated debate, Paul Ader argued that the Socialist party was a political party like any other, neither more nor less immune to political opportunism. While acknowledging the work of socialist leaders Jaurès, Vaillant, and Sembat, Ader (who had by now left the POF) also attacked Guesde's opposition to the CGT's campaign for the eight-hour day and the reformism of others

like Basly, Socialist leader of the miner's union. Were the syndicalists to ally with the Socialists, Ader argued, they would quickly become dominated by the SFIO. The unions would do better to remain autonomous; that way the Socialists would be forced to take them seriously.[77] Thus the FTAM adopted a position that foreshadowed the CGT's rejection of cooperation with the SFIO several months later.

How did the strike movement of 1903–1905 affect election outcomes, and how did syndicalist anti-electoral discourse influence voting behavior in the Aude?[78] The turn-of-the-century economic depression helped Socialists to maintain a base in winegrowing villages of the Aude, and associations like the groupes d'études sociales, cercles de jeunesse socialiste, and cercles républicains socialistes-révolutionnaires continued to function.[79] Socialists captured municipalities in winegrowing towns like Couiza, Salles, and Narbonne, and Socialist municipal councillors sat in Coursan, Sigean, Carcassonne, and Cuxac. Radicalism similarly retained its populist appeal and continued to court small vintners still suffering from the crise de mévente . Thus, although Socialists competed with Radicals in municipal politics, regional economic depression and similar positions on both labor issues and solutions to the wine crisis meant that the two groups continued to cooperate in national elections.

Even though Radicalism as a national political force had degenerated "into a party of the 'satisfied' political center, its leading deputies increasingly more hostile to Socialism than to the right," in the Aude (unlike southern departments such as the Hérault, where the formation of the Radical party meant the end of electoral alliances between Radicals and Socialists and presaged the collapse of the governmental Bloc des gauches), the two groups had not yet parted company.[80] In 1906 the SFIO agreed not to run candidates against Radicals in districts where Radicals had strong chances of winning (such as Narbonne II). Radicals likewise cooperated with Socialists in the face of rightist reaction to the 1905 law on separation of church and state.[81]

Although the 1906 elections resulted in a Socialist victory (Aldy) in the district around Narbonne (Narbonne I), in the Aude results overall paralleled those of the elections nationwide: a solid victory for Radicals (Table 23).[82] In the Aude, however,

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Radicalism's continued strength emerged not from approval of the use of force by the Combes government to enforce the "right to work." Rather, it stood both as a vote of confidence for local men who took the interests of bankrupt vignerons to heart and as a vote against right-wing extremism, which offered little promise for extricating the local economy from its present malaise.

The influence of the strikes of 1903–1905 on the 1906 elections in the Aude is difficult to assess. Socialist Félix Aldy gained votes both in villages in Narbonne I that had experienced strikes (ten out of eleven) and in six villages that had not. But Radicals did the same. As for the working-class vote, workers clearly did not follow the anti-electoral injunctions of syndicalist leaders nationwide; nonetheless, abstentions were especially high in the two villages where syndicalist leaders lived (in Coursan, 46 percent of the voters abstained, and in Cuxac d'Aude, 39 percent)—perhaps as a response to the syndicalists' anti-electoral rhetoric, but also surely as a manifestation of loyalty to local union leaders.[83] As we have seen, however, that loyalty was neither widespread nor enduring.

Revolutionary syndicalism in the Aude developed as both a social movement and a form of activism and protest. As a social movement, it grew out of a political culture indigenous to winegrowing communities and the work culture of skilled vinedressers. As a form of activism and protest, it proved to be a powerful manifestation of working-class solidarity in the vineyards. The rural unions succeeded in mobilizing workers to improve wages, hours, and working conditions and to win contracts as no political movement had yet managed to do. Perhaps their attention

to bread-and-butter reforms made them appear more "trade unionist" than revolutionary. Yet wage demands are not as rudimentary as they may at first glance seem; for "by incessantly raising the issue of the value of labor, the working class expresses its fundamental condition in opposition to capital."[84] This happened in the Aude—although, in recognition of the many small vintners who marched arm in arm with landless workers in these early labor conflicts, it was, we must add, in opposition to le grand capital . In this respect syndicalism succeeded as an alternative to socialism, as a movement that could extract concessions from employers—but only very briefly.

Once workers' demands were met they withdrew from the unions, and the ranks of rural syndicalism shrank, leaving behind a radical activist rump. The next chapter examines how the winegrowers' revolt of 1907 and its aftermath further weakened and divided the labor movement. For it called into question the collaboration of workers and small vineyard owners and, indeed, the whole nature of class solidarity, and led union leaders to attempt to barricade the unions in an uncompromisingly workerist vision of class struggle that distanced vineyard workers even more from the Socialist movement in the Aude.

Plate 1.

Coursan: the main street and town hall, ca. 1907

Plate 2.

Villagers in Fleury, Aude, before World War I (Private collection of Rémy Pech)

Plate 3.

Workers in the Narbonnais, ca. 1913 (Private collection of Rémy Pech)

Plate 4.

Women doing laundry in the Aude River, ca. 1900

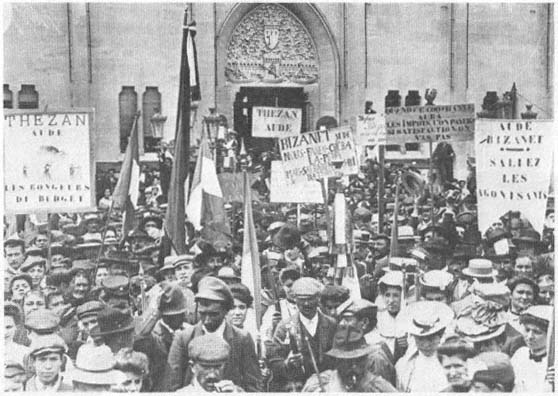

Plate 5.

Demonstrators in front of Town Hall, Narbonne, May 1907 (Photo Bouscarle-Sallis, Narbonne)

Plate 6.

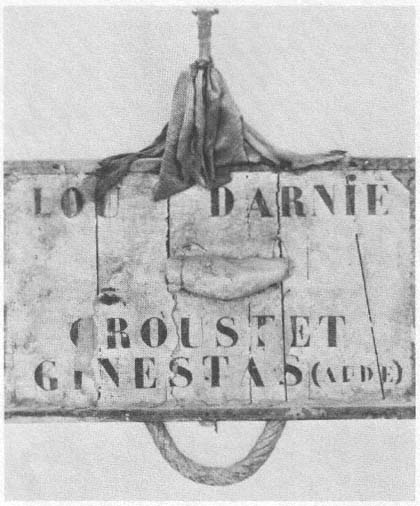

"The Last Crust": carried by demonstrators from Ginestas in 1907 (Photo

Bouscarle-Sallis, Narbonne)

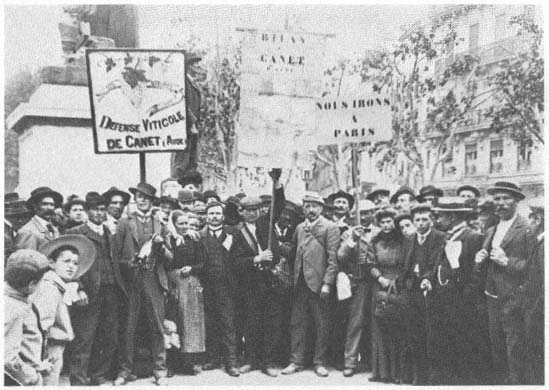

Plate 7.

Demonstrators from Canet, Aude, in 1907 (Photo Bouscarle-Sallis, Narbonne)

Plate 8.

Women from the Aude demonstrate in 1907 (Photo Bouscarle-Sallis, Narbonne)

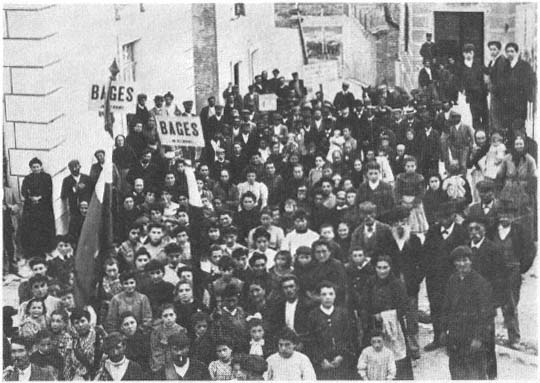

Plate 9.

Women and children from the village of Bages demonstrating in 1907 (Photo Bouscarle-Sallis, Narbonne)

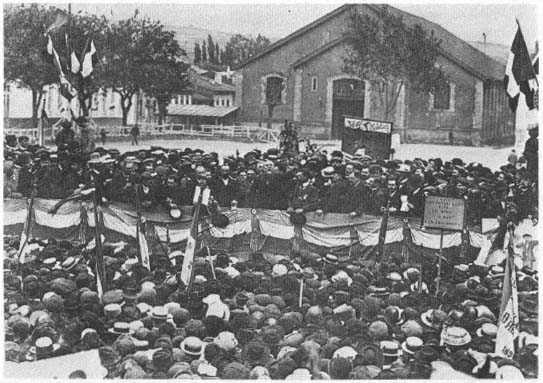

Plate 10.

Ernest Ferroul and Marcellin Albert addressing a crowd in 1907 (Photo Bouscarle-Sallis, Narbonne)