12

California to the End of the Century

Changing Patterns and the Development of New Regions

The simplest way to show what happened in California between, say, 1869, when Haraszthy left the state, and 1900, after a full generation of development had taken place, is by some statistics, graphically presented. A few details of graph 1 may be noted. The plateau from 1874 through 1877 conceals the fact that plantings increased mightily through those years—by an estimated 13,000 acres—so that the consequent overproduction destroyed prices. In 1876 grapes did not pay the cost of their picking, and many acres were uprooted or turned over to foraging animals. Through such drastic means, the industry had come back to a reasonably stable situation by 1880. The relatively small decline from 1886 to 1887 conceals another disastrous break in prices that year, which plunged the industry into a prolonged depression.

Accompanying the rising curve of production was another change, the rapid shift of dominance from south to north. Graph 2 comparing the San Francisco Bay counties to Los Angeles County will make this plain. The redistribution would be even more obvious if one took into account the continuing production of the Sierra foothill counties and the new production coming from the Central Valley counties. The reversal is clear enough, however; in the thirty years from 1860 to 1890, Los Angeles's share of the state's total sank from near two-thirds to less than a tenth; in the same span the Bay Area counties saw their share rise from little more than a tenth to near two-thirds, an almost symmetrical exchange.

The decline of the Southern Vineyard (as Los Angeles was called and as its

newspaper styled itself) was relatively sharp and quick. But that does not mean that winegrowing there disappeared, or was even much diminished to a casual eye. The news of phylloxera in Europe stimulated ambitious new planting, as we have seen in the case of Shorb and the San Gabriel Winery. Shorb's neighbor at the Santa Anita ranch, the Comstock millionaire E. J. "Lucky" Baldwin, built expansively in the late 1870s and early 1880s. He had 1,200 acres in vines in 1889, and promoted his Santa Anita Vineyard wines and brandies far and wide.[1] Another neighbor, L. J. Rose of the Sunny Slope Winery, tried, like Shorb, to exploit the opening created by phylloxera in European vineyards. Rose had been growing grapes and making wine for a decade when, in 1879, he determined on a great expansion. In that year he built what was called the largest and most modern winery in the state, with a capacity of 500,000 gallons to accommodate the yield of his 1,000 acres of vineyard. But the moment of the San Gabriel Valley's prosperity had passed for Rose as for Shorb. In 1887 Rose managed to sell the Sunny Slope Winery to a syndicate of English investors, who never recovered their money and whose experience considerably tarnished whatever appeal Los Angeles County winegrowing had as an investment.[2]

The onset of the Anaheim disease, which put an end to viticulture in Orange County, also helped to discourage the farmers of the San Gabriel Valley about the future of grapes and to turn them more and more to the all-conquering orange. Winegrowing in the south of the state therefore tended to shift eastwards to the region of Cucamonga, where viticulture was long established and the soil, a deep deposit of almost pure sand, was hardly suitable for anything else. When phylloxera appeared in California, this sandy soil protected the vines from the pest and so invited further plantings. Thus, the district, which had produced 48,000 gallons of wine in 1870, was producing 279,000 gallons in 1890.[3] It was here that Secondo Guasti, beginning in 1900, developed the "world's largest vineyard" (it ran to some 5,000 acres at its peak) and created a strong market for Cucamonga wine among the Italian communities of the East Coast..[4] The vineyards of the region persisted through Prohibition, depression, and war in the twentieth century, but fell victim at last to tract homes, freeways, airports, and industrial parks. Only rapidly diminishing vestiges survive in the 1980s.

Santa Barbara, Ventura, and San Diego counties all produced wine, but never very much—the total was 45,000 gallons in 1890, for example, and this was the work of scattered small producers. Nothing resembling an economically important industry ever arose in those counties, though there were some interesting enterprises. One of these was the Caire ranch on Santa Cruz Island, off Santa Barbara. The Frenchman Justinian Caire, a successful merchant in San Francisco, acquired the island around 1880; there, in addition to running sheep and cattle over the island's hills and valleys, he planted extensive vineyards and built a substantial winery of brick baked on the island. The island community was a varied mix of French, Indian, Mexican, Anglo, and Italian ranch hands and field workers. Wine-making was in the hands of French experts and the vineyards were tended by Ital-

1

Wine Production in California in Millions of Gallons, 1870-1900

Source: Report of the California State Board of Agriculture, 1911 (Sacramento, 1912)

ian workers, some of whom "spent their lives on the island and spoke no English." Among the hazards to viticulture on Santa Cruz were the wild pigs with which the island abounds. The vineyards included such varieties as Cabernet Sauvignon, Pinot Noir, Petite Sirah, and Zinfandel, and the wines acquired a good reputation, only to disappear, with so many others, under Prohibition..[5]

In San Diego County in 1883, through their El Cajon Land Company, a group of northern California wine men, including Charles Wetmore, Arpad Haraszthy, and George West, promoted the prospects of "viticulture and horticulture" on the

2

California Wine Production, North and South, 1860-90

Source: Report of the California State Board of Agriculture, 1911 (Sacramento, 1912)

27,000 acres of land they held for speculation..[6] Despite the high qualities claimed for Zinfandel wine grown in the county, winemaking was at best a sideline on San Diego ranches. There was, however, a considerable flurry of planting in San Diego following the collapse of the Anaheim region; the Italian investigator Guido Rossati reported that there were 6,000 acres in production in San Diego County in 1889, and 7,500 acres of vines not yet bearing..[7]

87

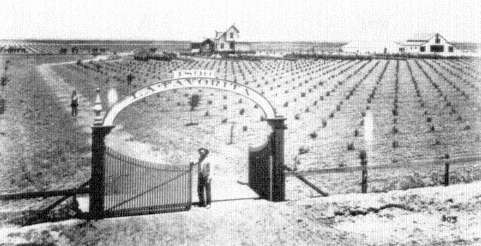

The Sunny Slope vineyard and winery of L. J. Rose in the San Gabriel Valley. With its thousand

acres of vines and half-million-gallon winery, this was one of the giants of the valley. It shared in

the general decline of the southern California vineyards, however, and after its sale to an English

syndicate in 1887 did not prosper. (Huntington Library)

88

A label of Justinian Caire's Santa Cruz Island Company, the only

wine producer on California's Channel Islands. (Author's collection)

A new development in the southern region was the growing of grapes for raisins rather than wine. Commercially successful trials with raisin grapes were made in Yolo County in 8867, but the great bulk of the trade soon shifted southwards. In 1873 raisin vineyards were set out in Riverside, in the El Cajon Valley of San Diego County, and along the Santa Ana River in Orange County, and these places soon became centers of raisin production..[8] The future lay with the region around Fresno, however, where planting also began in 1873 and where success was so rapid and complete that in barely more than a decade raisins were Fresno County's major crop. The raisin growers belong to the history of California winemaking because the grapes they grow have traditionally formed a part of the supply for the state's winemaking—rightly or wrongly. The mainstay of California raisin growing is the Thompson Seedless grape, introduced in 1872, which makes raisins of quality but at best a wine of entirely neutral flavor. Nevertheless, substantial tonnages of this grape in California have long been made into wine for blending or distilled into brandy for fortifying.

By 1870 the credibility of the idea that California was destined to be a great winegrowing country had been well established; it was also becoming clear that the southern part of the state had not succeeded in the essential matter of producing an attractive table wine: the combination of semidesert heat and the Mission grape stood in the way. A straw in the wind showing the new direction appeared in 1865, when the astute Charles Kohler of Los Angeles and Anaheim bought vineyards in Sonoma County. By 1870 he had "discovered" the Zinfandel, and from that time he planted his northern vineyards to it.[9] What Kohler was doing, and what Haraszthy and others had done before him, showed their opportunity to the smallholders and ranchers of the north. They had a reasonable selection of varieties, especially the Zinfandel, to replace the Mission grape, and these would yield acceptable dry wines from their more temperate valleys and hillsides. Anyone who possessed land not suited for irrigation or too rough for standard farming could put it into vines, as the newspapers, promotional agencies, and agricultural experts of the state were all urging everyone to do. The spirit of this time is expressed by Arpad Haraszthy, who had inherited his father's flair for publicity as well as his optimism, writing on "Wine-Making in California" in the Overland Monthly in 1872. The early winegrowers, he wrote, had not understood the importance of good varieties and proper soils, but that had now changed: "Every season brings us better wines, the product of some newly discovered locality, planted with choicer varieties of the grape, and entirely different from anything previously produced." Ultimately, he prophesied, California would produce a wine fit to take its place among the handful of the world's very finest..[10] All sorts of individuals and organizations were drawn into the work, and one can see several distinctive and clearly marked patterns taking shape in the 1870s.

First and most important was the individual farmer working on his own account and in his own style. More often than not the vine grower was also his own winemaker. Scores of the farm winery buildings put up at this time still stud the

towns and hillsides of the counties surrounding San Francisco Bay; typically they were simple, solid buildings, often of stone (or brick) or mixed stone and wood, providing a gravity-flow operation from upper to lower floor and a cool place of storage behind the stone walls of the lower stage.[11] A hand crusher and a hand press would suffice for the modest tonnage to be vinified, and the wines produced would perhaps go into vats and casks of native redwood—California's contribution to the medieval craft of the cooper, though not adopted as early as might be supposed.[12]

Many of the pioneering names of the 1850s continued to flourish: Jacob Gundlach in Sonoma, Charles Krug in Napa, and Charles Lefranc and Pierre Pellier in Santa Clara County, to name some of those whose wineries continue in operation to this day. To these pioneers, many new names were now added. Some of those still operating in California go back to this time, but very few indeed: Inglenook and Beringer in Napa County and Simi in Sonoma are notable; Cresta Blanca, Wente, and Concannon, all (originally) in the Livermore Valley, belong to the early 1880s, as do Geyser Peak and Italian Swiss Colony in Sonoma County and Chateau Montelena in Napa. The overwhelmingly greater number of the new establishments of this era were destined to briefer lives, and even the hardier of these could not survive Prohibition: Aguillon, Bolle, Cady, Chauvet, Cloverdale, Colson, Cralle, Delafield, Doma, Dry Creek, Eagle, Fischer, Glassell, Gobruegge, Green Oaks, Gunn, Hoist, Laurel Hill, Lehn, Live Oak, Meyer, Michaelson, Naud, Nouveau Médoc, Palmdale—such a list of vanished names might be extended into the hundreds.

There are no reliable statistics on the number of winemaking establishments in California in the nineteenth century. What is certain is that there was a rapid and unstable growth. The instability is well illustrated by the figures (perhaps approximately reliable) for the number of registered wineries in 1870 and 1880: in the first year there were 139 wineries; in the second, after the crash of 1876, only 45.[13] These figures must be for the more visible wineries only: the number of people actually making wine at any time was far greater. In the survey made by the Board of State Viticultural Commissioners in 1890, for example, 711 growers reported that they made wine, and even that figure is well below what must have been the case.[14] But whatever the actual number may have been, the point is that it kept going up and down.

The counties ringing San Francisco Bay, though they were clearly coming to dominate the industry, were not the only scenes of new development; the attraction to winegrowing was felt throughout the state wherever the chances seemed good. The expatriate Englishman (afterwards a prolific and exceedingly bad novelist) Horace Annesley Vachell put in a vineyard on the Coast Range in San Luis Obispo County in 1882, and viticulture on the Estrella Creek (or River) in that county went back a number of years earlier,[15] as it did in the town of San Luis Obispo itself, where, not long after 1859, Pierre Dallidet planted a vineyard and opened a winery.[16] In a few other counties that are now, in our time, coming to be

important in California winegrowing, only the barest of starts was made in the nineteenth century. In Mendocino County, for example, there were only two wine-makers listed in the state board's 1891 directory; the same source lists but two for Lake County, and for Monterey none at all, though there were some ten names listed as grape growers. The possibilities of the central coast of California, roughly between Monterey and Los Angeles, though not exactly unknown, lay unrecognized and undeveloped until very recent years. The fact is good evidence that the winegrowing map of California is far from its final form.

In an unsystematic way much was being learned about the possibilities of the vast number of soils, sites, and microclimates in California, but one can hardly say that the diverse regions of the state had been fully prospected. Nor have they been even today. It would not be anything like as soon as Arpad Haraszthy and others thought before the possibilities of the state's territories were sufficiently known to allow the right varieties of grape to be matched to the right soil and climate. That is a work that still has many years before it in California, to say nothing of the rest of the United States. But certainly much had been done in a rough-and-ready way by the end of the 1880s.

A new region, hitherto unattractive to settlement, begins to be heard from in the 1870s. The interior of the state, south of San Francisco and between Coast Range and Sierra, now the gigantic cotton, almond, tree fruit, and grape factory called the Central Valley, was then still pretty much what the Spaniards had called it, tierra incognita . Its main products for many years would be raisins and other fruit unfit to drink: the huge modern wine production of Kern, Tulare, Kings, Stanislaus, and Fresno counties lay in the future. But significant work had begun. And it was evident, from the beginning, that the growers of the Central Valley were going to make a lot of wine. Even if the bulk of the grapes they grew went to raisins, the scale of winemaking operations was much bigger here on an average than elsewhere.

Token plantings of grapes had been made in scattered parts of the Central Valley in the 1850s and 1860s, but the region was almost wholly given over to cattle grazing until the opening of the railroad through it at the beginning of the 1870s. Then speculators began to try what the possibilities of this virtually untouched territory might be. The center of development was the new town of Fresno, laid out in the middle of the valley and named by the Central California Railroad in 1872. An experiment in irrigated farming in that year produced sensational results on the Easterby ranch ouside Fresno, and the agricultural exploitation of the region was off and running. [17] The valley was hot and arid, but the touch of water seemed to release a magic fertility.

The honor of introducing the grape belongs, by all testimony, to Francis Eisen, a Swedish-born San Francisco businessman who had just bought property in Fresno County, and who put in vines to see what they might do. That was in 1873. These grapes, as a writer put it in 1884, turned out to be "the key which has unlocked nature's richest stores."[18] Eisen went on to develop his property on a scale

that was to be a model for agricultural development generally in the Central Valley: by the end of the seventies he had 160 acres in vines; in 1883 he had 200 acres; by 1888 he had 400, and his winery had been built up to a capacity of 300,000 gallons.[19] Eisen's original vine plantings had included raisin varieties as well as wine varieties, and it was the raisin that was to dominate Fresno County viticulture in the early days, as it does still. But winegrowing was established at the same time, and grew only less rapidly than the raisin trade. It is interesting to note that Eisen, in the untried Central Valley, experimented with a wide range of varieties, including a number of the American hybrids such as Lenoir, Cynthiana, and Norton.[20] The great object of the early Fresno growers was to find a way to prove that they could grow something other than sweet wines in the blazing heat of their valley, and the native American varieties were tried for the sake of their higher acids in blends with such vinifera as Zinfandel. It is also notable that the Mission was not part of the varietal mix in Fresno; its defects were now too well known to be doubted, and there was, by this time, no need to depend on it.[21]

Agriculture in the Central Valley was never an affair for the small proprietor. Only irrigated farming was possible, and the costs of preparation for that were too great for most individuals: the main irrigation works had first to be provided; then the ground had to be levelled, ditches dug, dikes and levees built, hedges planted, roads made—all before any planting went on. In these circumstances two kinds of proprietorship grew up. Either the land was developed by wealthy individual capitalists or corporations, or it was developed by the "colony" system, something on the model of the Anaheim scheme twenty years earlier. A group would form for the purpose of pooling its resources, buying land, and then dividing the property, to be paid for on long terms. The first of these was the Central California Colony in 1875. That was followed by a string of others—the Washington Colony, the Scandinavian Colony, the Fresno Colony, and, ominously, the Temperance Colony. Several of these associations had winegrowing as an object: the original Central California Colony, for instance. The Scandinavian Colony, founded in 1879, developed a considerable winery; it had a capacity of 100,000 gallons in the nineties, when it was taken over by the California Wine Association.[22]

The large-scale example set by the pioneer firm of Eisen was followed by a number of other Fresno vineyards and wineries. Among the most notable of these were the Eggers Vineyard, the St. George Vineyard, the Barton Vineyard, and the Fresno Vineyard Company. They may be dealt with briefly. The Barton Vineyard, founded in 1879, was the showplace of the region, splendid on a level of display that put it high among California attractions. Robert Barton, a former mining engineer, spared no expense to make his new property elegant and handsome in every detail: his fences, his hedges, his pleasure grounds, his winery, his barns, his mansion, his vineyards—all moved the admiration of the journalists who wrote about it: "a princely domain," one called it; "a paradise," said another.[23] Barton had five hundred acres of bearing vineyard by 1884, from which he made both dry and sweet wines from standard varieties such as Zinfandel and Burger; he also had a

89

The bareness of the scene and the large scale of the operations that characterized Central Valley

winegrowing are both clearly evident here. (From Jerome D. Laval, As "Pop" Saw It [1975])

90

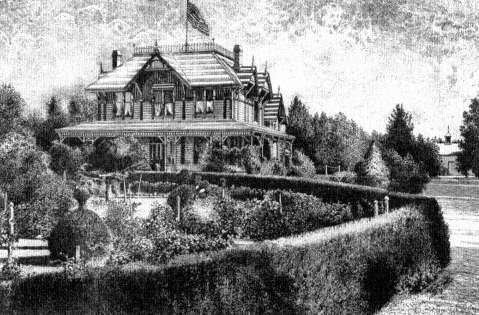

The Barton Estate Vineyard at Fresno, the unchallenged showplace of the Central Valley in

the pioneer days; founded in 1879, it was sold only eight years later to a syndicate of English

investors for $1 million. To contemporaries, the Barton Estate was "a princely domain" by contrast

to the bare flats of the valley around it. (From Frona Eunice Wait, Wines and Vines of California [1889])

mixture of other, more exotic varieties for trial, especially for sweet wines. In 1887, at the high point of English interest in California vineyard property, Barton sold his estate to a syndicate of English investors for a million dollars—a sensational transaction for Fresno, where winemaking was barely more than a decade old. Unlike the Sunny Slope Winery of L. J. Rose, which was sold to English investors at about the same time, the Barton Vineyard continued to grow; by 1896, as the Barton Estate Company Ltd., it had a capacity of half a million gallons, supplied by over 700 acres of vineyard. Its manager, installed by the English owners, was a Colonel Trevelyan, a survivor of the Charge of the Light Brigade.[24]

The other early wineries of Fresno had little notable about them apart from their tendency to grow to great size. The St. George Vineyard was the work of an immigrant Silesian named George Malter, who, like Robert Barton, had been a mining engineer before becoming a grape grower and winemaker, beginning in 1879. His vineyards covered 2,000 acres by the end of the century, and his winery was one of the largest in the state before Prohibition put an end to it.[25] The Eggers Vineyard and Winery, of 225,000-gallon capacity, was the property of a San Francisco land company that began vineyard development in 1882;[26] the Fresno Vineyard Company was also the work of a San Francisco corporation, in which the wine merchants Lachman & Jacobi had an original interest.[27] It was begun in 1880 and was soon developed to a capacity of 500,000 gallons. The Eggers Vineyard and the Fresno Vineyard Company were both essentially bulk wine producers, whose wines were shipped in volume to San Francisco and elsewhere to disappear into blends. All of these big Fresno district wineries were largely devoted to sweet wine production by the end of the century, though all had begun with a determination to make dry table wines. They failed to convince the skeptics that good dry wines could come from the heat of the Central Valley and were forced to turn to the production of vast quantities of anonymous sweet wine. This development was probably inevitable at the time: the production of good dry wines would not be possible until a much more scientific control, both of grape growing and of winemaking, had been worked out. Meantime, the growth of the Fresno vineyards went on. In 1908 there were 100,000 acres of grapes: 60 percent of this acreage was in raisin varieties, 38 percent in wine varieties, and 2 percent in table varieties. Acreage would go on increasing even after Prohibition.[28]

Perhaps the most highly regarded of the new regions exploited for vines around this time was the Livermore Valley in Alameda County, a pleasant region of oak-studded coastal hills a few miles inland from San Francisco Bay. Here an English sailor named Robert Livermore had made his way in 1844 and had set up as a rancher. He planted vines and made wine, but only, as most ranchers did, for his own needs.[29] The floor of the valley is a deep gravel bed, suited to the vine and not fit for much else; the valley, shut off from the Bay by the Berkeley hills, is hot, and yet, surprisingly, it has from the outset made good dry white wine, for many, many years a thing that the rest of California had trouble in producing. From a token 40 acres in the 1870s the valley's vineyards leaped to over 4,000 acres by

1884, a development largely owing to the promotional genius of Charles Wetmore, who invested in Livermore in 1882 and thereupon persuasively declaimed its virtues to a responsive state.[30] Livermore also profited from the fact that good varieties of the grape—notably the Semilion—were planted there in the first days of development. The region never had to pass through a phase of dependence on the Mission. It was, moreover, a region largely developed by wealthy men, as the glamorous names of their properties suggest: Chateau Bellevue, Olivina, Mont Rouge, Ravenswood, La Bocage. The small farmers did not lead here but followed.

Large-Scale Investment in California Winegrowing

Livermore was hardly alone in the combination of wealth and winemaking. While hundreds of farmers and small businessmen were planting vines and making wine in commercial quantities, there were at the same time a good many individuals and organizations of great wealth busied in the same work. They define the second pattern of the development of this generation in California. The vine has always been one of the ornaments of wealth and power. Greek and Roman aristocrats owned vineyards and competed with their wines as they might compete in racing fine horses or in collecting rare manuscripts. In the Middle Ages princes of the church as well as secular princes owned vineyards and patronized the arts of viticulture and enology. The same attraction operated in California. The early San Francisco banker William Ralston, who had a hand in California enterprises ranging from silk mills to mines, all financed by lavish and irregular loans from the Bank of California, was a major promoter of the Buena Vista Vinicultural Society, Haraszthy's ambitious organization in the 1860s. The collapse of the bold schemes of the Buena Vista Society and the bizarre death of Haraszthy were matched by Ralston's fall to ruin and his death in San Francisco Bay. As early as 1859 one of the state's first millionaires, the hard-drinking renegade Mormon Sam Brannan, sank a large part of his fortune in a property in the northern Napa Valley where, having named the place Calistoga, he set out to create both a health resort at the local hot springs (California plus Saratoga Springs yielded "Calistoga") and large-scale vineyards. He failed in the speculation, though the vine-growing part was successful enough. Brannan commissioned an agent to send thousands of cuttings of the best varieties to him from Europe, and in a couple of years had some 200 acres in vines. Brandy rather than wine seems to have been Brannan's main production for the market, and he was trying to get Ben Wilson of the Lake Vineyard to take over the Calistoga wine interest by 1863. [31] Though Brannan was the first Californian of great wealth to take up winegrowing, he did not take it very far.

The most ambitious and sustained application of California's early wealth to winegrowing came from Leland Stanford, one of the Big Four with Collis P. Huntington, Charles Crocker, and Mark Hopkins; wartime governor of California, U.S. senator, and founder of the university named for his son, Stanford was one of

the great powers in the state throughout the latter half of the nineteenth century. Stanford's interest in California wine went back at least as far as 1869, when he bought property at Warm Springs, along the southern shores of San Francisco Bay in Alameda County, from a Frenchman who had some seventy-five acres of grapes planted there. Stanford installed his brother Josiah on the property, and there the brothers began making wine in 1871. By 1876 production at Warm Springs Ranch was up to 50,000 gallons.[32]

In 1880 Stanford travelled with his family to France and there paid visits to some of the great chateaux of Bordeaux: Yquem, Lafite, and Larose among others. Whether this experience was the direct inspiration for what followed next is not known, but it seems likely, for on his return Stanford determined to become a great wine producer. The flourishing enterprise of L. J. Rose at Sunny Slope, with its big new winery, may also have stimulated Stanford's competitiveness. In 1881 Stanford began buying large quantities of land along the Sacramento River in Tehama and Butte counties, between Red Bluff and Chico, with the announced aim of growing wines there that would rival the best of France. The property was part of the old Lassen grant and already had a winegrowing history. Peter Lassen himself had planted Mission vines as early as 1846; in 1852 he had sold what remained of his grant to a German named Henry Gerke, who extended and improved the vineyards and successfully operated his winery through most of the next three decades.[33]

When Stanford took over, things changed dramatically: in one year a thousand acres of new plantings were added to Gerke's modest seventy-five; vast arrangements of dams, canals, and ditches for irrigating the ranch were constructed, fifty miles of ditch for the vineyards alone; a number of French winegrowers were brought over and housed in barracks on the ranch; a winery, storage cellar, brandy distillery, warehouses, and all other needful facilities were built, no expense spared. The new-fangled incandescent lights were installed in the fermenting house so that work could be carried on night and day during the critical time of the vintage. All the while Stanford continued to add to the acreage of his ranch, now called the Vina Ranch after the nearby town that Henry Gerke had laid out. Lassen's original grant from Mexican days extended over 22,000 acres, but Lassen had not been able to hold it long, and by the time Gerke appeared Lassen's ranch had dwindled to about 6,000 acres. Gerke, too, had sold off parts of the property, so that Stanford's first purchase was but a fragment of the original Mexican grant. Stanford simply kept on buying once he had started, however, and by 1885, when he appears to have thought that he had enough for his purposes, the Vina Ranch spread over 55,000 acres of foothill pasture and valley farmland—some 20,000 acres of the latter.[34]

The moral of this enterprise, larger and more costly than anything else ever ventured in California agriculture to this point, was not long in appearing: size anti wealth are not enough to make up for lack of experience. The circumstances were all wrong for what Stanford wanted to do, and though the Vina property was lovely to the eye and richly productive in all sorts of crops, it did not and never

91

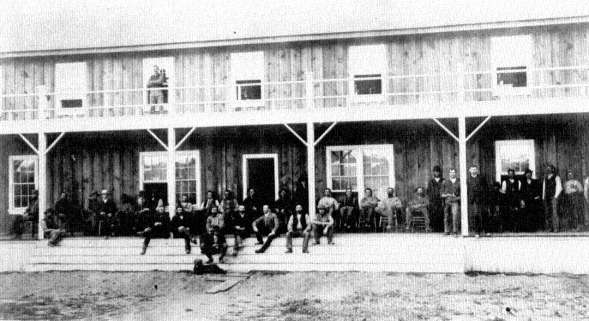

Workers at Leland Stanford's Vina Ranch on the verandah of their boarding house. There are thirty-seven

men and one dog in this picture, taken in 1888. and they were probably only a fraction of those employed

on the ranch and in the winery. The picture was taken by George C. Husmann, son of Professor George

Husmann. (Huntington Library)

could have made fine table wines. It was, in the first place, too hot in the summer for the grapes from which the noble wines come. The ranch lies in what is called, in the classification of California winegrowing lands, region five, the hottest of the five classifications, more like Algeria than Alameda. Its soil, too, was richer than that which good wine grapes need—they always prefer the poorer to the richer; and, finally, there was not enough experience yet in California with the bewilderingly wide range of Old World grape varieties and their possibilities. As has already been said, the matching of the right varieties with the right soil and climate is a work still going on and bound to continue for many years. It cannot be hurried, since not until the trial has been made can one know whether the right match has been found and one can hardly expect that what has required centuries in Europe will occur overnight here.

The force of these considerations was made clear within a year or two of the first vintage at Vina, which took place in 1887 with a harvest of several thousand tons (three earlier harvests had been sold to other winemakers). By this time there were 3,575 acres of vines planted, and a wine cellar with a capacity of two million gallons of storage had been built to receive the yield from this sea of vines. To supervise the work, Stanford had hired one of the master winemakers of the state,

Captain H. W. McIntyre, who had been winemaker to Gustave Niebaum at Inglenook in the Napa Valley and president of the state association of grape growers and winemakers.[35]

Evidently, all that could be done had been done, and yet the wine was a disappointment. No clear report about the character of the table wine produced is on record, but the circumstantial evidence is eloquent. The original selection of varieties, for one thing, was mistaken. Stanford planted Burger, Charbono, Malvoisie, and Zinfandel in his first expansion of the Vina vineyards; the cuttings, incidentally, came from the San Gabriel Valley vineyards of L. J. Rose, and this itself was a bad sign.[36] Burger wine was a Rose specialty, and he had particularly promoted it as greatly superior to the Mission. That was true, no doubt, but still faint praise. Burger, for white wine, does not make a distinguished table wine no matter where it is grown; the Malvoisie is an excellent source of sweet wines; only the Charbono and Zinfandel, red wine grapes, can be expected to yield good sound wines for the table, but that is when they are grown in the cooler hills and valleys of the state. Later, Stanford introduced a selection of other varieties, including the Riesling (though Gerke seems to have had this grape before Stanford's day), Cabernet Sauvignon, Malbec, Sauvignon Blanc, and Semillon.[37] But the lesser varieties continued to dominate, and in any case the finer varieties could never have produced wine comparable to what they yield in a suitable climate. As though to underline the uncertainties of Stanford's experiment, native American grapes were also included in the mix of varieties that were tried at various times: the Catawba, Herbemont, and Lenoir, varieties that have since entirely disappeared from California viticulture.

By 1890, only the fourth vintage at Vina, the entire huge production of 1,700,000 gallons of wine from 10,000 tons of grapes was distilled into brandy.[38] No more telling comment could be made on the collapse of Stanford's hope to rival the best that Bordeaux could produce. This is not to say that the vineyards and winery were a failure; only that the much-publicized aim of producing outstanding table wine was not met, and could not have been met. What could be done was to produce quite good sweet wines—baked sherry, angelica, port—and large quantities of brandy that acquired a high reputation. One experienced New York dealer of the time recalled Vina brandy as "more like cognac than anything made in this country," [39] and there are other testimonies more or less agreeing with this. The Vina angelica was judged the best of that sort exhibited at the great Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893. [40] But these compliments, and a scattering of others like them, are a sad anticlimax after the high and boastful intentions with which the Vina experiment started.

Stanford's winegrowing was not confined to Vina or to Warm Springs. He had grown grapes on his Palo Alto ranch in San Mateo County ever since he purchased it in 1876; in 1888 he built a winery there, perhaps in recognition of the fact that something better was needed than Vina was able to provide. Wine was produced and sold there under the Palo Alto label, on the Stanford campus, down to 1915,

but the scale of the enterprise was not comparable to that at Vina, and Stanford does not appear to have put a special effort into its success.[41]

For all the fact that it was widely and regularly written up in the California press, as a sort of standing feature subject, the Vina Ranch seems to have had curiously little impact on the life of the state. Its practices in grape growing and wine-making did not point the way to the future but gave only a sort of object lesson of what was to be avoided. The labor on the ranch was mostly provided by Chinese and Japanese workers, isolated from the general life around them.[42] And the production of the ranch was almost entirely sold to New York markets, so that a bottle of Vina brandy or of Vina wine was rarely seen by a California buyer.[43] The whole thing seemed to exist outside the view of the ordinary citizen of the state.

Stanford died in 1893. The Vina Ranch had already passed into the endowment of Stanford University, and once Stanford himself was no longer around to indulge his hobby interest in the property, his widow and the university trustees followed a very different style in its management. Captain McIntyre took his departure; Mrs. Stanford fired 150 employees and cut the salaries of everyone who remained. Vineyard acreage was reduced and land planted to other crops like alfalfa and wheat.[44] All the while, the university grew more and more embarrassed by its position as a major producer of wine and brandy in the face of growing prohibitionist disapproval of such an unholy connection between Demon Rum and godly education. Worst of all, David Starr Jordan, the university's first president, was a vocal prohibitionist himself. Stanford University's somewhat shamefaced part as proprietor of a great vineyard persisted, however, until 1915, when a final harvest of 6,000 tons from the vines of Vina was sold off to Lodi winemakers and the vines themselves uprooted. A few more years and the ranch itself had been dispersed by sale. After passing through different hands, the central part of the old ranch, including the vast cellar, with its two-foot-thick walls of brick, was sold to the Trappist monks in 1955; now they cultivate their gardens in silence there, at Our Lady of New Clairvaux.[45]

To judge from a number of the published accounts of Stanford's "failure" at Vina, their writers take a barely concealed satisfaction in the thought of a very rich man's inability to buy what he wanted. The Vina Ranch was in fact a double disappointment for Stanford, for he had meant it not only to produce fine wines but to be an inheritance for his beloved son, Leland, Jr., whose early death in 1884, at the very moment when the great vineyard plantings were going on at Vina, must have taken the heart out of the enterprise for the father.

But if the story invites some threadbare moralizing, it did not discourage other men of wealth from venturing on the chances of winemaking. Nothing so grandiose has since been attempted by an individual in California, but the record of late nineteenth-century winemaking in the state is studded with the names of the rich, the fashionable, and the powerful. Two of Stanford's fellow millionaires and fellow senators owned extensive vineyards and made wine: the Irishman James G. Fair—now remembered for his Fairmont Hotel in San Francisco—at his Fair

Ranch in Sonoma County, and George Hearst, father of William Randolph, at the Madrone Vineyard in Glen Ellen, Sonoma County.[46] In Napa, the Finnish sea captain Gustave Niebaum, made rich from the traffic in Arctic furs, bought the Watson vineyard, called Inglenook, near Rutherford, in 1879 and proceeded to make of it not merely a model winery but a successful model. Niebaum could afford to take his time, being a wealthy man, and wisely did so, with distinguished results. Not until after he had had a chance to study the subject in Europe did he make his decisions. He chose superior varieties, constructed a state-of-the-art winery, and put the work in the hands of experts. The results were excellent, and were quickly recognized as such.[47] In the Livermore Valley Julius Paul Smith, with a fortune derived from the California borax trade, made a speciality of fine winegrowing at his Olivina Vineyard; like Stanford, Smith had visited Europe to study its vineyards and wines; unlike Stanford, he chose a site that rewarded his expectations. Olivina Vineyard wines had a great success in New York, where Smith opened a large cellar.[48]

Smith had two prosperous neighbors who also took up winegrowing: at his estate of Ravenswood, south of Livermore, the San Francisco Democratic boss Christopher Buckley—the "Blind White Devil," as Kipling tells us he was called[49] —amused his intervals of rest from the implacable wars of city politics by making wine from his 100 acres of grapes.[50] At the Gallegos Winery, in nearby Irvington, Juan Gallegos, a wealthy coffee planter from Costa Rica, built a wine-growing enterprise on a large scale, and had the technical assistance of the distinguished Professor Eugene Hilgard of the university. The Gallegos vineyards, of 600 acres, incorporated the old vineyard of Mission San Jose from the days of the Franciscans. When the Gallegos Winery was destroyed by the great earthquake of 1906, it had become a million-gallon property.[51]

Far away in the south of the state, General George Stoneman, Civil War hero and governor of California, set out a large vineyard and built a winery in the early 1870s at his magnificent estate of Los Robles, near Pasadena (or the Indiana Colony, as it then was); another governor, John Downey, joined with the banker Isaias Hellman in developing their winemaking property in Cucamonga.[52] Downey, it will be remembered, was the governor who had appointed Haraszthy a state viticultural commissioner in 1861. Just south of Los Angeles, Remi Nadeau, once mayor of Los Angeles, developed a mammoth vineyard of over 2,000 acres beginning in the early 1880s; poor Nadeau committed suicide in 1887, and the vineyard property seems to have gone into residential subdivisions in the land boom that swept over southern California in that year. Not, however, before a winery, an "immense affair" according to contemporary description, was built to receive the expected flow of grapes from the Mission, Zinfandel, Trousseau, and Malvoisie vines on the property.[53] Nadeau's was not only the largest but the last moneyed plunge into winegrowing in Los Angeles County.

Winegrowing on a big scale was undertaken not only by wealthy individuals but by stock companies, after the earlier model of the Buena Vista Vinicultural So-

ciety. The most notable of such attempts in the eighties was that of the Natoma Vineyard, near Folsom in Sacramento County, the property of the Natoma Land and Water Company, itself one of the enterprises of Charles Webb Howard, one of California's baronial landowners. The company first experimented with different varieties, and then began planting vineyards on its land in 1883; by the end of the decade, it had 1,600 acres of wine grapes and had built a winery of 300,000 gallons' capacity. The operation was self-contained and tightly organized: a foreman's house and barns were provided for each 400 acres of vines, and at the winery itself, at the center of the property, there were houses for the superintendent, an accountant, and their families.[54] The expert George Husmann, writing in 1887, declared that the Natoma Vineyard was the most exciting development in California, "a most striking illustration of the rapid advance of the viticultural interests in the state,"[55] and an influence for the general improvement of the industry through its experiments with different varieties suited to California. The original mover and shaker of the project, Horatio Livermore, left in 1885, however, and his plans were not carried through as originally drawn up. The California wine trade had entered into its long depression, and by 1896 the company had leased its vineyards to other operators.[56]

Italian Swiss Colony and the Italian Contribution

Another sort of big-scale enterprise begun in California in the eighties recalled earlier experiments like that at Anaheim, but with considerable difference. Andrea Sbarboro was a native of Genoa who had arrived in this country in 1850, aged twelve, and earned prosperity by organizing building and loan societies in California. As a way to help his fellow-countrymen in the state, he had the idea of creating a large grape-growing business on the principle of the savings and loan society. The original investments would be made by capitalists who could afford them, but the workers would, through payroll deductions, acquire shares in the company and could, if they liked, convert their property into land. Sbarboro's intention was to provide steady, dignified work for the many Italians who had arrived in San Francisco in large numbers and sunk to the bottom of the labor pool. No doubt, as a prudent man of business, Sbarboro hoped to make money, but as a student of the many cooperative experiments of the nineteenth century, and as a devoted reader of John Ruskin and Robert Owen, Sbarboro also hoped to create a work of genuine social philanthropy. Thus the Italian Swiss Colony was born (there were originally a few Swiss from Ticino in the affair, but it very soon became exclusively Italian).[57]

The first steps went well. In 1881 a company was formed, and 1,500 acres of hill and valley were bought far north in Sonoma County, near Cloverdale. Here, in a village called Asti after the Piedmont town famous for its wines, the workers were settled and planting began in 1882. Workers were easy to recruit, for the company gave good terms: $30 to $40 a month, plus room, board, and as much

wine as a man could decently drink. Preference was given, according to the bylaws, to Italians or Swiss who had become U.S. citizens or who had declared their intention of becoming citizens: this was to be a permanent community.[58] Two developments, however, soon altered the original purposes. The first was that the Italian workers wanted no part of Sbarboro's investment scheme. The proposal to deduct $5 each month from their wages looked to them like financial trickery. Suspicious to a man, they all refused to participate. Thus, as a company publication put it some years later, "they rejected the future that their more sagacious fellow-countrymen had planned."[59] The Italian Swiss Colony had, therefore, to be carried on like any other joint stock company, though it continued to be marked by a strong paternalistic tendency. A second change in the original purposes came about through the collapse of the market in 1886. The idea of an Italian Swiss Colony specializing in grape growing had been formed when wine grapes were bringing $30 a ton; by 1887, when the first substantial tonnage appeared, the price was $8, not enough to meet the costs of production. The directors determined that the colony would enter the wine business itself and authorized the construction of a 300,000-gallon winery. By these steps the cooperative vineyard of Sbarboro's original vision became an integrated winemaking company.[60]

By very careful management, and by the severe discipline of paying no dividends for its first sixteen years, the Italian Swiss Colony gradually made its way. It was lucky in its officers: Sbarboro continued to take a close personal interest in the work; Charles Kohler, the dean of California wine merchants, was a shareholder and a member of the company's auditing committee; Dr. Paolo de Vecchi, the vice president, was a highly successful San Francisco surgeon; the president and general manager was Pietro Rossi, a graduate in pharmacy of the University of Turin. Despite the phylloxera then spreading through California, they managed to develop extensive vineyards, as well as coping with the wild fluctuations of an unstable wine market. When the company at last had its wine ready, the California dealers' best price was a derisory seven cents a gallon. Rossi responded by organizing the company's own agencies in order to reach the eastern markets.[61] They were able to ship in quantity to New York, New Orleans, and Chicago—the three cities where the still very restricted American wine market was concentrated. Before long, Italian Swiss Colony wines were being sent to foreign markets as well, through agents in South America, China, Japan, England, Germany, Switzerland, Belgium, Denmark, Norway, and Sweden. The New York branch held stocks of a million gallons. The company did a good trade in altar wines. And it industriously collected prizes and awards at expositions around the world, to be displayed or its labels.[62]

By the turn of the century, the Asti premises were the largest source of table. wine in California, and the huge wine cistern—500,000 gallons' capacity—that Sbarboro had had built to hold the bumper vintage of 1897 in order to keep it off the market had become one of the tourist wonders of California.[63] By 1910 the vineyards of the Italian Swiss Colony extended over 5,000 acres, including proper-

ties at Madera, Kingsburg, Selma, and Lemoore in the Central Valley in addition to the original Sonoma plantings. Company literature boasted that there were more superior varieties of grape grown at Asti than anywhere else in the United States, and certainly the winery poured out a profusion of kinds: Italian Swiss varietals included zinfandel, carignane, mataro, barbera, cabernet, pinot, riesling, pinot blanc, and sauvignon blanc. The company developed a sparkling moscato, and distilled large quantities of both brandy and grappa. Its banner wine, familiar in all American markets, was its "Tipo," sold in imitation chianti fiaschi in both red and white varieties.[64]

The shareholders who endured the long years of profitless operation were finally well rewarded. The company's winery capacity in x 910 had reached 14,250,000 gallons, and the stock, originally worth around $150,000, was now valued at $3,000,000 and would continue to grow.[65] Sbarboro and Rossi both built handsome "villas" at Asti, which they used as summer retreats, from which they could survey their work—the winery, the village houses, cooper's shop, post office, school, railroad station, and church—the latter built in the shape of a barrel among the vineyards. Sbarboro could, with pardonable pride, look on the evidence of a success rather different from, but probably far greater than, anything he had imagined back in 1881. Unluckily, he had also the misfortune of living long enough to see the catastrophe of the Eighteenth Amendment, which wiped out all the results of his philanthropic labor. Sbarboro was one of the first among the leaders of California winemaking to perceive the threat of prohibition, and he became a leading publicist in the national campaign for wine and temperance. He had the bitter fulfillment of seeing all that he had worked for fail.

It is not necessary by this point to repeat that the growth of winemaking in this country was the work of a wide variety of different immigrant communities; but the success of the Italian Swiss Colony reminds us that the Italians were a relatively new element. There had been Philip Mazzei in eighteenth-century Virginia, but he seems to have had no successors, or at least none who left a record. That changed very quickly now. Italian immigration to the United States had formed only one half of one percent of the total immigration in the decade of the Civil War. By 1881-90 it had increased more than tenfold, and in the next decade it tripled again. Much of this tide came to California. The Italians were all the more welcome after the Oriental Exclusion Act of 1882 shut off the flow of Chinese labor to the vineyards and wineries of the state.

Though it can be given only incidental mention, the Chinese contribution to California wine deserves more than that; it is, however, largely undocumented, and so much of it is lost to history. What can be said is that in the thirty years between their first immigration in 1852, when they were sent to the gold mines or to the railroad embankments, and the Exclusion Act of 1882, they were widely used in the California wine industry, from vineyard to warehouse. Scattered remarks in print attest this, and a few old prints and photos show Chinese at work in vineyard and press house, but no connected account of the Chinese in California winegrowing

92

A Chinese worker tends the receiving bin for grapes at the Fair Oaks Winery in Pasadena, Chinese

workers appear to have been as much a part of the winemaking scene in the south as in the north

of the state, (Huntington Library)

has yet been put together.[66] As early as 1862 Colonel Haraszthy was employing Chinese labor at Buena Vista and defending his practice against an already strong public hostility.[67] In the south, as we have seen already, J. De Barth Shorb had discovered the virtues of Chinese labor in his vineyards by 1869; his neighbor and rival L.J. Rose had followed Shorb's lead in using Chinese labor by 1871,[68] and thereafter one may reasonably suppose that they were a standard part of southern California winemaking as they already were in the north. Perhaps the best-known picture of winemaking in nineteenth-century California, the drawing made by Paul Frenzeny in 1878, has as one of the most prominent parts of its design the figures, of Chinese coolies bringing in baskets of grapes from the field and treading them out over redwood vats.[69]

To return to the Italians, the earliest of them in California winemaking were very early indeed: the Splivalo Vineyard and Winery in San Jose went back to 1853. though Splivalo did not acquire it until the late fifties. Earliest of all, perhaps, was: Andrea Arata, who planted his Amador County vineyard in 1853. These were isolated instances, however.[70] And when there was a considerable Italian immigration

to California, few of the newly arrived Italians were in a position to set themselves up independently—a fact to which Sbarboro's cooperative scheme of the Italian Swiss Colony had been a response. The fate of most who went on the land, then, was to labor in the fields. There were exceptions: Vincent Picchetti was in business in Cupertino by 1877, Placido Bordi at the same place in 1881;[71] but it was not until the late eighties that Italian names began appearing with any regularity among the proprietors. In the south, Giovanni Demateis founded his winery at San Gabriel in 1888; Giovanni Piuma his in Los Angeles in 1889; Secondo Guasti opened his Los Angeles winery in 1894.[72] In the Central Valley two wineries founded in the 1880s followed the expansive tendencies of that region by growing to a great scale: the Bisceglia brothers at Fresno, who opened in 1888, eventually built their enterprise to a capacity of eight million gallons; Andrew Mattei at Malaga, near Fresno, pro cessed the yield of some 1,200 acres of vineyard.[73] In the north, Bartholomew Lagomarsino was established in Sonoma County; G. Migliavacca was one of the earliest of all, for he set up as a winemaker in Napa in 1866.[74]

Though they were beginning to make an important contribution to California winegrowing before the nineteenth century was over, the Italians were far from dominating the scene, as they have sometimes seemed to do since Repeal. Certainly one would get that impression from the fiction and drama written about the families who make wine in California: the writers almost all choose Italians as their image of the California winegrower.[75] The French family Rameau in Alice Tisdale Hobart's The Cup and the Sword is a rare exception. Perhaps it is true that the Italians were more loyal to the vine than any other group during the trying times of Prohibition, so that the names that first came forth on the morning of Repeal were those of the faithful Italians: Rossi, Petri, Martini, Gallo, Cribari, Vai. But the prominence of Italian names on the winemaking scene of California is an effect of our particular perspective. To an observer of the California industry at the moment when Prohibition shut it down, its character would have been thoroughly mixed, perhaps a little more evidently European than most American institutions, with its many Beringers, Schrams, Lefrancs, Gallegoses, Niebaums, and Sbarboros, but not clearly dominated by any one of these nationalities and not excluding an abundance of people with names like Tubbs, Baldwin, Dalton, and Keyes. If I were to make a guess on the question (and it would be something more than a guess), I would say that there were more growers and winemakers of German descent, both in California and in the rest of the country, than of any other origin before Prohibition.

Communal Organizations and Winegrowing

The traditional link between religious communities and winegrowing went back to the beginnings of California, when the missions introduced the art and mystery of wine. It is interesting to note that one, at least, of the old mission vine-

93

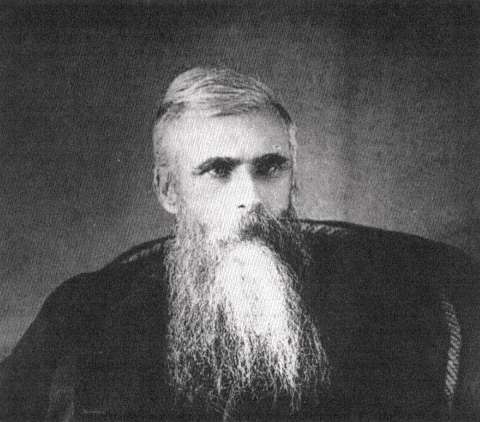

Leader of the Brotherhood of the New Life, Thomas Lake Harris (1823-1906) founded

winegrowing communities in both New York and California. Their produce was, he held,

not mere wine but the divine breath of God. At Fountain Grove, outside Santa Rosa, the

Brotherhood developed a major winery that prospered even after Harris, the founder,

had been driven from California. (Columbia University Library)

yards was brought back about this time, in the eighties, when California wine-growing had entered on a new order of importance. Under the patronage of the archbishop, Father Kaiser at Mission San Jose began making wine for the church from the vines still growing at the Mission.[76] But, as wine had never been an important part of the economic life of the missions originally, neither was it to be so now. For some latter-day religious communities, however, it was to be important—most notably for a strange melange of diverse people brought together on the basis of an equally strange compound of mystical principles and calling themselves the Brotherhood of the New Life. The founder, Thomas Lake Harris, was English-born, but brought up in the "burnt-over" region of upstate New York, the most fertile source of new religious growth in the whole United States. Harris gradually

pieced together all sorts of elements—Swedenborgian, Universalist, Spiritualist—into a new rule of life and attracted to himself a small community to carry out the practices of his invention: the members included Englishmen, Yankees, Southerners, even a few Japanese. Among the Englishmen was Laurence Oliphant, a writer and traveller of some fame, who had once sat in the British Parliament. With his wife, he brought a good deal of money into Harris's community.[77]

The New Life began in Dutchess County, New York, in 1861, first at a village called Wassaic, and then in the town of Amenia, where, it is said, winemaking was the business of the community. Since the Brotherhood were there only four years, their winemaking cannot have progressed very far. In 1867 Harris moved the com munity to Brocton, on the shores of Lake Erie, in Chautauqua County, New York, where he had purchased some 1,200 acres. This was the era of the grape craze in the East, and of expansionist activity in the winegrowing industry of the Lake Erie region. Harris decided to join the action, or, as he put it, to devote the community to "the manufacture and sale of pure, native wine, made especially for medicinal purposes."[78] For this was not to be just ordinary wine. The community's produce would share in the special virtues of its religious practice: the wine of the New Life was infused with the divine aura and opened the drinker to the creative breath of God Himself. More prosaically, Harris meant to make wine from the Salem grape, one of the hybrids produced by E. S. Rogers, in which Harris had put his faith and his money, for he had paid for the rights to grow it.[79] One wonders whether he chose this grape for the sake of its winemaking qualities or for its religious name? His "New Found Salem Wine," as it was called, did not prove entirely satisfactory, however (though whether on divine or merely sensuous grounds is not clear), and the Brotherhood at Brocton soon tried other varieties as well as the Salem. Harris himself kept a vineyard at his house, called Vine Cliff, where he could experiment with different varieties. Meantime, in 1869, he sold all of his stock of Salem vines to a Lockport nurseryman.

In his work at Brocton, Harris had the advantage of good help. A Dr. J. S. Hyde, from Missouri, was his wine expert, assisted for a time by a Dr. Martin, from Georgia. Another member, Rensselaer Moore, who came from the grape-growing Iona Island in the Hudson, understood the propagating and growing of vines. Between them, these men made a success of the community's venture. By 1870, only three years after their move to Brocton, the small community—it numbered between 75 and 100 members—had a vintage of 15,000 gallons and had built a solid masonry underground storage vault a hundred feet long.[80] The winemaking enter prise was called the Lake Erie and Missouri River Wine Company, though why it had that name is not clear.[81] Perhaps Hyde's Missouri origins were thus indicated, or perhaps they used Missouri wines in their own production?

No sooner were things running smoothly at Brocton than Harris decided to move to California, probably for the same reason that urges people today to leave the wintry shores of Lake Erie for the Pacific Coast, though Harris gave religious reasons as well. In any case, in 1875 he bought 400 acres of land just north of Santa

Rosa (where Luther Burbank arrived in the same year), named the property Fountain Grove, and set about to develop it. The community at Brocton continued to operate, selling its wine to a New York firm using the "Brotherhood" label until the gradual shift to California was complete.[82] Not all the New Yorkers went to California, but the Brocton establishment was wound up in 1881.

At first the California colony supported itself by dairying, but vines were soon planted and by 1883, when Harris hoped for a vintage of fifteen to twenty thousand gallons, the entire estate had been concentrated on winegrowing.[83] From this point on Fountain Grove prospered. By continued purchase Harris ultimately enlarged the property to about 2,000 acres, of which 400 were in vines, and nearly as many more in orchards. The winery, brick-built, three stories high, steam heated, and scientifically equipped, had a capacity of 600,000 gallons, and production grew rapidly to use that capacity: 70,000 gallons were made in 1886; 200,000 in 1888.[84] The winemaking remained under the charge of Dr. Hyde, who had accompanied Harris west from New York. The vineyards grew good varieties—including, it is said, Pinot Noir, Cabernet, and Zinfandel—and red table wine was the staple product. This was sold mainly in the East, through a New York agency that included a wine house, restaurant, and bar at 56 Vesey Street. The winery even published its own illustrated journal, the Fountain Grove Wine Press . So far as I know this is the first example of a house journal or newsletter in the American wine industry.[85]

Harris, who held the title to all this property, lived in something like splendor compared to the provincial standards of Sonoma County in those days. His house, of many rooms, was finished in fine woods, ornamented with stained glass, and surrounded by gardens and fountains. It also contained what a contemporary de scribed as "perhaps the most extensive library in northern California," where Harris could play at science and poetry.[86] The other members of the community lived in two buildings, men in the "Commandery" and women in the "Familistery."

Though Fountain Grove prospered, no one so striking and controversial as Harris could expect to lead a tranquil life, especially not when he propounded sexual theories that could only scandalize a California farm community in the 1880s. Harris taught that God is bisexual, and that everyone, man and woman, has a celestial counterpart with whom to seek eternal marriage. Unluckily, the counterpart is elusive: it may move from one body to another, and in any case it is hard to know, for sure where it dwells, and when. Yet the main business of life is to find one's counterpart. Hunting the counterpart, then, looked to outsiders like simple promiscuity, never mind about the celestial sanctions. It did not help the reputation of Fountain Grove that the partners in civil marriage were supposed to be celibate, since civil marriage did not, except by the rarest accident, bring together genuine counterparts. And Harris, a copious writer who set up a printing press at Fountain Grove before a wine press, put forth stuff about how the world is filled with tiny fairies who live in the bosoms of women and sing heavenly harmonies inaudible to worldly ears. It is no wonder that rumors grew until scandal broke. It is perhaps more remarkable that Harris stayed on at Fountain Grove so long as he did. At last

in 1892, urged by newspaper furor, he left for England, never to return to Fountain Grove.[87]

In 1900, six years before his death, Harris sold out to a small group of the faithful, including Kanaye Nagasawa, a Japanese variously styled baron or prince, who had been one of the earliest converts to the New Life and one of Harris's closest assistants.[88] Nagasawa kept the winery and vineyards until his death in 1934, after which they passed into other hands and at last expired in 1951. The Fountain Grove label was purchased by a neighboring winery and may still be seen on bottles of California wine, but it is not what it was.[89] The estate itself has been eaten away by the city of Santa Rosa, and so this phase of the New Life, at any rate, has returned to the spirit.

While Fountain Grove's wine business was developing, another Sonoma County community, some distance to the north, almost within sight of the Italian Swiss Colony at Asti, had been founded on the basis of communistic winegrowing. This was the Icaria Speranza commune, and its example completes the sequence of communal groups that chose winegrowing as a way to realize the dream of self-fulfillment in a new land. The Huguenots, the German Pietists, and the Rappites were seeking religious freedom; the French in Alabama and the Germans in Missouri were seeking to transplant a European culture intact; the colonists of Anaheim and Asti were looking for simple economic sufficiency. The Icarians of Cloverdale were looking, in a way, to combine all of these things.

They were a secular group, but professed the religion of True Christianity; they were communists but not political, preferring to change the world by the force of good example; they taught universal brotherhood, but required the ability to read and speak fluent French for membership.[90] Their roots in this country went back to 1848, when a group of Frenchmen, inspired by the utopian communism of Etienne Cabet revealed in his Voyage en Icarie , arrived in Texas to create a model community. They soon migrated to Illinois, then to Iowa, suffering dissension, schism, and material hardship along the way.[91] The California venture was a last gasp in the struggle that had begun over thirty years earlier for the original Icarians. Armand Dehay, an idealistic barber associated with the Iowa community, led the way to California, where in 1881 he purchased 885 acres along the Russian River three miles south of Cloverdale and at once began laying out a vineyard of Zinfandel grapes. The Icarians, good Frenchmen all, had planted a Concord vineyard during their sojourn in Iowa, and the main hope of the California colony was to make viticulture the basis of independence.

The times were propitious—the Italian Swiss Colony venture began the same year, inspired by the same expansive market for grapes—and the Icarians, consisting of a few families only, began work with good hope. In one year's time they had 45 acres in vines, and were planning a distillery as well as a winery. In 1884 they were joined by a further migration from the Iowa colony, raising their numbers to about fifty-five people. They held their property in common, but they lived their lives in fairly usual fashion. In the main house they met to dine and to enjoy their

social occasions, but the different families lived in separate dwellings rather than in some regulated communal arrangement.[92]

Their luck soon ran out. They had counted on the sale of their Iowa property to meet their California debts but ran into legal trouble and got nothing; they lacked both labor and money to carry out the developments that their scheme re quired; and finally, as had happened to the Italian Swiss colonists too, when they at last had a grape harvest to sell, they had nobody to buy it. The writing on the wall was clear by 1886; in 1887 the society could not meet its debts and was dissolved, the property passing to the ownership of some of the individual colonists, several of whom remained to tend the vineyards and make wine as small proprietors rather than as the communitarians they had hoped to be.[93] Armand Dehay, the prime mover of the group, was one of those who remained; with his brother he grew grapes and made wine at the Icaria Winery. Thus the three different community experiments made within a few years and a few miles of one another in Sonoma County—the Fountain Grove Brotherhood, the Italian Swiss colonists, and the Icarians—all failed to reach their spiritual or political goals. They all succeeded at viticulture, however.

Winegrowing in Sonoma County: a Modal of the Whole

Winemaking had been tried by almost every imaginable sort of person or agency in nineteenth-century California—rich men, poor men, large companies and small companies, Godless cooperatives and religious communities. But the standard remained the relatively small independent grower, more likely to be tending a vineyard of ten or twenty acres than of a hundred or more. These were the people who had been attracted into the industry in the sixties and seventies, and not many of them would have moved beyond their modest beginnings into any thing very large or impressive. As George Husmann wrote in 1887:

We have thousands, perhaps the large majority of our wine growers . . . who are com paratively poor men, many of whom have to plant their vineyards, nay, even clear the land for them with their own hands, make their first wine in a wooden shanty with a rough lever press, and work their way up by slow degrees to that competence which they hope to gain by the sweat of their brow.[94]

To get an idea of the character of California winegrowing in the eighties one may look in some detail at the scene in a particular region. Sonoma County, a larger and more diverse winegrowing region than any other of the north coastal counties, provides a rich source, a sample of which will provide the flavor of the whole.

The king of Sonoma County in those days was Isaac De Turk, of Santa Rosa, who came to California from Indiana in 1858, began planting vines in 1862, and a quarter of a century later presided over the biggest business in Santa Rosa: his winery had a capacity of a million gallons, and took up an entire block along the

railroad tracks on the west side of town, where, the historian reports, it was "no uncommon thing to see a train load of cars leave his warehouse loaded with wine for Chicago, St. Louis or New York."[95] "Claret" was De Turk's great speciality, made from the Zinfandel for which Sonoma was already famous. Other wineries in the state bought their claret from De Turk to sell under their own labels.[96] His standing in the industry was recognized by his appointment to the original State Board of Viticultural Commissioners in 1880.

At the other extreme from De Turk's large, factory-scale enterprise were great numbers of individual farmers, still unspecialized, who grew grapes among other crops and who perhaps made wine themselves or sold their crops to nearby wineries. Such farmers were scattered all over Sonoma County and represent hundreds of others like them to be found up and down California. These are typical descriptions: Joseph Wilson, near Santa Rosa, had "forty-five acres . . . devoted to the cultivation of wine grapes of the Zinfandel and Grey Riesling varieties. . . . Twelve acres are planted with apples, pears, cherries, and plums. . . . The rest of his land is devoted to hay and grain." John Laughlin, of Mark West Creek, had "twenty acres of orchard, twelve acres of wine and table grapes, and seventy acres of alfalfa." Edward Surrhyne, in the Vine Hill district west of Santa Rosa, tended a little of everything. His orchard grew peaches, pears, apples, prunes, "and other fruit." He had fifty acres of grapes, including Zinfandel and something called Ferdeges for wine, which he made on his own property.[97]

A few of these farmers, incidentally, were women: Mrs. Eliza Hood, widow of the Scotsman William Hood, ran the Los Guilicos Ranch, including its winery and 100 acres of vines; Mrs. Ellen Stuart presided over the Glen Ellen Ranch at the little town named for her, Glen Ellen, where her neighbor Mrs. Kate Warfield operated the Ten Oaks Ranch. Both of these ranches included grape growing and wine-making in their activity.[98]

In between De Turk's huge enterprise and the domestic operations of the Sonoma farmers, there were a number of substantial wineries going back to the days of Haraszthy's Buena Vista in the 1860s. Buena Vista was now much decayed, but others were prospering. Jacob Gundlach, for example, made highly regarded wines on his Rhinefarm, neighboring Buena Vista, and sold them through wine vaults in San Francisco and New York. At Glen Ellen the pioneer Los Angeles wine man, Charles Kohler, had made a showplace of his Tokay Vineyard and winery, producing all kinds of wine on a large scale for sale through his own agencies.[99]

Most striking of all in the survey of Sonoma's winegrowing industry as it stood in 1889 is the mix of nationalities, which contains most of the elements already identified in California's history. There were Italians other than those at the Italian Swiss Colony: the Simi brothers, whose winery still operates today, had set up at Healdsburg in 1881; not far away, and beginning in the same year, the brothers Peter and Julius Gobbi ran their Sotoyome Winery; at Windsor, to the south, B. Arata had settled in 1884 and set out a vineyard of 18 acres (he was, like the

Simi brothers, from Genoa, and like so many Genoese he had been a sailor; now he tended Zinfandels in the valley of the Russian River).[100] There were, rather unusually, several Englishmen in the business. Thomas Winter, a sailor originally from Nottingham, raised vines on his ranch on Dry Creek. Near Sonoma, Thomas Glaister, a north countryman from Cumberland, after episodes in Chicago, New York, and Australia, had built up an estate including 150 acres of vines and a winery of 100,000 gallons' capacity specializing in white wine. Another native of Nottinghamshire, John Champion, raised grapes near Cloverdale and also man aged the Gunn Winery near Windsor, a small new property owned by an absentee proprietor. Earliest of the Englishmen was John Gibson, a Kentishman, who settled in the Sonoma Valley in 1856, planted a vineyard, built a winery, and operated a hotel halfway between the towns of Sonoma and Santa Rosa.[101]

There was a higher than usual proportion of French to be found too. The little community at Icaria has already been described, and it may be that it was attracted to the county in part by the example of the French growers and winemakers al ready established there. The first to come was Camille Aguillon, the son of a wine-maker from the Basse Alpes. Aguillon had been drawn to California by the Gold Rush, but worked mostly as a gardener before making his way to the town of Sonoma. He planted no vineyard, but instead specialized in making wine in a building on the town plaza; it eventually became the town's largest—"Aguillon's famous winery," Frona Wait calls it.[102] Next was the Alsatian George Bloch, who made the transition from a restaurant in San Francisco to a vineyard at Dry Creek in Sonoma in 1870. With another Frenchman, Alexander Colson, Bloch founded the small Dry Creek Winery in 1872. Bloch continued to operate it after Colson left the partnership in 1884, when with his brother John he founded a winery, also on Dry Creek, called Colson Brothers. The brothers were from the Department of Haute Saâne, the sons of a vigneron and winemaker. Jean Chauvet, a native of Champagne, had been settled near Glen Ellen since 1856 but did not begin wine-making until 1875; by 1888 he was producing 175,000 gallons, making him one of the major individual producers in the county. In the same year that the Colson brothers built their winery, another pair of French brothers, Auguste and N. C. Drayeur, natives of Lorraine, opened their "Two Brothers Wine Store Vaults" in Healdsburg. Like Aguillon, they grew no grapes but selected from the local vine yards. Finally, there was Jean Baptiste Trapet, a native of the Côte d'Or brought up in viticulture; he had a five-year adventure in California in the 1850s but returned to France, lived as a vine grower, and served on the town council of Beaune. The phylloxera drove him back to California in 1877, where he settled as a neighbor of the other Frenchmen in the Dry Creek region, growing his own vines and making his own wine.[103]

Despite the presence of the French, English, and Italians, Sonoma County was in the first generation after Haraszthy preeminently a region of Germans. Gundlach has already been mentioned. To his one might add a long list of good German names, many of them borne by men who had come from the winegrowing regions

94

The Geyserville Winery of Julius Stamer and B. W. Feldmeyer, proudly flying the American flag

in token of its owners' identity as American citizens. Stamer, the winemaker, came from Hamburg;

Feldmeyer, from Oldenburg, was a carpenter. The two men met in St. Helena in the early 1880s and

founded their Sonoma County winery in 1884. Producing dry red and white wines only, with a capacity

of 75,000 gallons, the winery typifies the industry in Sonoma at the end of the nineteenth century.

(From Illustrated History of Sonoma County [1889])