Management of Riparian Vegetation in the Northcoast Region of California's Coastal Zone[1]

Dan Ray, Wayne Woodroof, and R. Chad Roberts[2]

Abstract.—Riparian vegetation has important habitat and economic values. The Coastal Act requires protection of both of these sets of values. Local coastal plans have attempted to resolve this policy conflict by protecting riparian corridors and habitat patches. Protection of large areas of riparian vegetation by land-use regulation has proven difficult.

Introduction

Northwestern California riparian systems include a complex of biological and economic resources seldom surpassed in richness. Riparian systems provide nesting and foraging areas for a diverse wildlife fauna, protect water quality essential to anadromous fisheries, hold substantial commercial timber, and affect floodwaters and sediment movement in ways essential to local agriculture. State and local policies encourage protection of all of these values—a policy mandate requiring government officials to balance competing goals. Developing policies which can be implemented and are technically sound and politically acceptable is a difficult task.

Riparian Systems in the Northcoast Region

The northcoast region of California's coastal zone includes the seaward portions of Del Norte, Humboldt, and Mendocino counties. The coastal zone's inland boundary, established by the Coastal Act of 1976, is typically 914 m. (1,000 yd.) inland from the mean high tide. The boundary runs inland in four large bulges to include significant estuarine, habitat, and recreational areas at Lakes Earl and Talawa in the Smith River delta; Freshwater, Stone, and Big lagoons near Redwood National Park; the Eel River delta, and the Ten Mile estuary and dunes complex in Mendocino County. The largest of these bulges, the Eel River delta, extends inland almost 8 km. (5 mi.) above the river's estuary and up to 18 km. (11 mi.) from Pacific Ocean beaches.

Riparian systems within the northcoast region of the coastal zone are located along most minor streams and all of the major rivers. Their vegetation is characterized by an overstory typically dominated by red alder (Alnusrubra ), Sitka spruce (Piceasitchensis ), and redwood (Sequoia sempervirens ). Black cottonwood (Populus trichocarpa ) is commonly dominant on the floodplains of the Mad and Eel rivers. Pacific wax-myrtle (Myrica californica ), bigleaf maple (Acermacrophyllum ), California-laurel (Umbellulariacalifornica ) and Pacific red elder (Sambucuscallicarpa ) are also common trees and shrubs in mature riparian areas. Willows (Salix spp.) are typical pioneers in disturbed areas. In mature associations, these species are joined by vines, epiphytes, and other herbaceous and woody plants to form a diverse, vertically stratified plant community. For a more complete description of riparian flora, see Roberts etal . (1977) or Proctor etal . (1980).

Wildlife populations in northcoast riparian areas have not been thoroughly surveyed, but lists from comparable areas in inland forests (Marcot 1979; Thomas 1979), coastal Oregon and Washington (Proctor etal . 1980), and other sources (Harris 1973; Monroe 1974) suggest that up to 140 species of birds and 37 species of mammals utilize northcoast riparian forests at some time during the year. Many of these species (wading birds such as egrets, cavity nesters, and some raptors, warblers, and mammalian predators) depend upon mature riparian forest for some portion of their nesting or feeding habitat requirements. The importance of riparian forests may be increased in the northcoast region due to the relatively poor habitat status of upland redwood forest (Leipzig 1972; Harris 1973).

Riparian forests on smaller coastal streams also protect water quality by shading stream

[1] Paper presented at the California Riparian Systems Conference. [University of California, Davis, September 17–19, 1981].

[2] Dan Ray and Wayne Woodroof are Coastal Analysts, North Coast District, California Coastal Commission, Eureka, Calif. R. Chad Roberts is Environmental Analyst, Oscar Larson and Associates, Eureka, Calif.

channels and intercepting and filtering runoff from adjacent uplands. This water quality protection is critical in maintaining aquatic species, including anadromous fish, in coastal rivers and streams (Thompson etal . 1972).

Riparian zones in the northcoast also hold a number of economically important resources. Redwood, Sitka spruce, and red alder are important to local timber processors as sources of lumber, plywood, wood chips, and pulp. With the advent of biofuel-thermoelectric power plants, other riparian species such as black cottonwood may become economically important. Beyond the standing timber value, riparian zones are preferred sites for long-term timber production because of their soil quality and the beneficial effects of periodic flooding. For example, annual growth of commercial redwoods in riparian zones of the Big, Albion, and Navarro rivers of Mendocino County is from 1.2 to 1.4 times that of adjacent upland forest sites (USDA Forest Service 1965). Agricultural uses also benefit from productive riparian soils. Flood-borne sediment deposition on the alluvial valleys of the Garcia, Eel, Mad, and Smith rivers has created highly productive soils more than 1.8 m. (6 ft.) deep. These bottomland soils are up to twice as productive as other local farmlands on diked wetlands or upland terraces (McLaughlin and Harradine 1965). Agricultural land owners also use riparian vegetation as a source of firewood for domestic use.

Use of riparian land in the northcoast region has been dominated by the exploitation of these economic resources at the expense of fish and wildlife habitats. Riparian forests were typically among the first used for commercial timber harvest because of the very high lumber volumes they held and the easy access to rivers and estuaries they offered. Level streambeds were modified to allow construction of cordoroy roads or narrow-gauge railroads used to transport sawlogs. Large expanses of Sitka spruce/black cottonwood forest were cleared for agricultural use. An estimated 6,900 ha. (17,000 ac.) of riparian forest were converted to grazing land in the coastal zone of Humboldt and Del Norte counties. The major floods of 1955 and 1964 caused substantial damage to forested riparian lands on the Smith, Klamath, and Eel rivers. Subsequent construction of flood control projects on the Smith River and at Redwood Creek caused additional losses of riparian vegetation.

Existing northcoast riparian forests are a remnant of this history of development. Relatively large riparian areas remain along Elk Creek and the Klamath River in Del Norte County and the Eel River in Humboldt County. Cutover riparian forests in many small forested watersheds and commercial timberlands along the Ten Mile, Big, Albion, and Navarro rivers in Mendocino County have gone through succession to progressively more diverse second growth forests with high habitat values. Riparian woodland patches can still be found scattered in narrow bands along most streams and in unused portions of farms or residential areas.

Coastal Commission Policy for Management of Riparian Systems

The Coastal Act of 1976 (Public Resources Code 30000 etseq .) created the California Coastal Commission and six regional commissions and charged them with regulating development to protect coastal resources. The Act requires local governments to prepare local coastal plans implementing these policies and authorizes the regional coastal commissions to review local plans and regulate development within the coastal zone until local coastal plans are approved. The Act grants the Commission power to regulate most development affecting riparian systems. The Act does not authorize the Commission to regulate logging operations under timber harvest plans approved by the State Board of Forestry. Instead, the Act empowers the Commission to designate unique coastal resource sites as "special treatment areas" within which timber harvests are carefully regulated under the California Forest Practices Act. Coastal Act policies require protection of sensitive habitat areas and commercial forest lands and encouragement of coastal agriculture. Section 30240(a) of the Coastal Act states: "Environmentally sensitive habitat areas shall be protected against any significant disruption of habitat values, and only uses dependent on such resources shall be allowed within such areas."

Sections 30241 and 30242 require that: "the maximum amount of prime agricultural land shall be maintained in agricultural production to assure the protection of the areas' agricultural economy"; and ". . . lands suitable for agricultural use shall not be converted to non-agricultural uses unless (1) continued or renewed agricultural use is not feasible, or (2) such conversion would preserve prime agricultural land or concentrate development . . . . Any such permitted conversion shall be compatible with continued agricultural use on surrounding lands."

Section 30243 provides that: "long term productivity of soils and timberlands shall be protected and conversions of coastal commercial timberlands in units of commercial size to other uses or their division into units of non-commercial size shall be limited to providing for necessary timber processing and related facilities."

These policies express desirable objectives for state and local action but their application in specific areas may lead to conflicts. Purchase of extensive areas along the Big River in Mendocino County was proposed by the USDI Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) in 1979 to assure protection of its sensitive estuarine and riparian systems. However, the purchase would convert commercial timberlands to non-commercial use. Installation of riprap or other devices along eroding Eel River banks is essential to the protection of prime agricultural lands, yet the bank

protection would impede the natural erosion and accretion processes that have been essential to the maintenance of Eel River riparian systems.

Local farmers assert that Coastal Act policies provide priority to the agricultural economy and so should permit clearing of riparian vegetation for pasturelands. The California Department of Fish and Game (DFG) argues that the same policies require riparian systems be protected against even removal of domestic firewood. Industrial foresters believe the Coastal Act policies permit conversion of deciduous hardwood vegetation to commercial conifers.

Anticipating such conflicts among Coastal Act policies, the Legislature found in Section 30007.5 of the Act that: ". . . such conflicts should be resolved in a manner which on balance is the most protective of significant coastal resources . . . broader policies which, for example, serve to concentrate development in close proximity to urban and employment centers may be more protective overall than specific wildlife habitat and other similar resource policies."

Based upon this guide, northcoast region staff biologists have turned to conservation ecology theory to formulate policies which identify and protect significant resources of the region's riparian systems.

Conservation Ecology

In the past decade, ecologists have gained insights relating to conservation problems generated when development occurs in or adjacent to relatively undisturbed natural systems. An important work on this subject is that of Pickett and Thompson (1978), which builds upon the theoretical base formed in MacArthur and Wilson (1967). Pickett and Thompson began with concepts from island biogeography, broadened them to include habitat islands in seas of different habitat, and applied the results to conservation issues.

Their basic conceptual conclusion is that if a particular area of undisturbed habitat is reduced in size, the effect is qualitatively like that upon "land-bridge" islands (especially if the "connections" to other, similar habitat patches are severed). The remnant habitat islands are "supersaturated" with species, a phenomenon due to a predictable relationship between island areas and species richness. Reducing the habitat area always leads to a reduction in the number of species that a habitat patch will support; this is an empirical result, verified many times. After developing this point, the authors made several recommendations for habitat conservation. Habitat patches should be large, undisturbed, more-or-less round, and either close to or connected to other, similar patches. In addition, the ecology of the patch should be taken into consideration, including such factors as within-patch successional processes, "patch longevity," and patch replacement rate.

Wilcox (1980) developed these arguments further. By focusing on "insular ecology" Wilcox pointed out that habitat patches should be as large as possible. Since any "habitat" has fewer species than a larger, nearby habitat area (an empirical result), the larger the island, the fewer the missing species. Species typically added with greater patch size are the less common species which are usually the management target. Wilcox presented a technique for calculating species number reductions, given a reduction in patch size. That technical discussion is beyond the scope of this report, but the conclusion drawn is that the greater the habitat area reduction, the greater the magnitude of species lost, and the faster their rate of disappearance.

The relationship between habitat patch area and species diversity has been studied by other investigators. Galli etal . (1976) studied bird species diversity in New Jersey forest islands surrounded by other habitat. Thirty islands were studied ranging in size from 0.008 to 24.3 ha. (0.02 to 60 ac.). Bird species diversity increased in the predicted fashion, and the significant variable was shown to be island area. Until a minimum size threshold was crossed, only "edge" species were present. As the area increased further, "interior" bird species were added, though they tended to be present at low densities. A follow-up study in New Jersey by Forman etal . (1976) concluded that diversity continued to increase with patch size up to the 40 ha. (100 ac.) point. In fact, Forman et al. concluded that the highest bird species diversity would not be reached until areas in excess of 40 ha. were sampled.

Forman etal . (ibid .) also concluded: a) over half of all species encountered were "minimum-area" species, found in larger patches; b) larger patches contained more species than an equal areas of smaller patches; c) most of the increase in diversity in patches larger than about 2.8 ha. (7.0 ac.) was due to insectivorous species; and d) large mammal-eating birds were only present on the larger patches. As management considerations, these authors recommended that patches be as large as possible, and that many smaller "stepping-stone" islands be maintained.

The relationship between body size and geographic range size was discussed by Schoener (1968). He showed that, in general, larger birds required larger territories. Apparently the relative densities of the kinds of food eaten by large (especially predatory) birds decrease as bird body weights increases. This is apparently why such species as Pileated Woodpeckers and Buteo hawks have large territories and, conversely, why there are relatively few of these birds (disregarding the basic question of distribution of their required habitats). Schoener's empirical result dovetails with the field results of Forman et al. (1976), adding credence to the recommendation for large habitat patches.

Further, Gates and Gysel (1978) found that forest edge-nesting bird species were more subject to both predation and cowbird parasitism than interior-nesting species. Forest edges acted as a guide to both predators and cowbirds; nesting success increased in proportion to the distance of the nest from the forest edge. There may be a minimally acceptable patch size which ensures availability of enough area for edge-nesting species to avoid nest losses from predators and cowbird parasitism.

Based upon this analysis, we believe that a premium value should be placed on large expanses of undisturbed riparian vegetation. Such large, undisturbed areas will fulfill "minimum-area" requirements of those large and/or uncommon species which require conditions in patch interiors. A second priority should be for smaller areas of undisturbed riparian vegetation in preference to larger areas of disturbed vegetation. These "stepping-stone island" patches can answer the needs of some smaller "interior" species; if population densities randomly fluctuate to low levels, they can help dispersing individuals recolonize larger patches. Finally, retention of some riparian vegetation along all watercourses is essential. While a narrow strip is not in itself satisfactory habitat, it can help in dispersal, and adds minor foraging area for species in nearby, larger patches.

Policies for Riparian Management

North Coast District local coastal plans being prepared by local governments or already approved by the Coastal Commission generally include riparian vegetation management policies consistent with these recommendations. Where commercial timber use is planned for riparian areas, the conflict between timber production and habitat protection has been resolved through the forest practices rules for special treatment areas. The rules provide protection for many components of riparian systems. Riparian vegetation management policies and their applications in typical riparian systems within the region are discussed below.

Riparian Management on Small Coastal Streams

The northcoast region includes about 240 small coastal streams and their tributaries. Typically, these streams drain watersheds from 1.6 to 6.4 km. (1 to 4 mi.) inland from the coastal zone and would be considered first- and second-order streams under Strahler's (1964) stream ordering rules. Their channels are usually contained within well-defined gorges cutting through the coastal terrace. Riparian vegetation is best developed and most diverse immediately adjacent to the stream channel, although Sitka spruce, redwood, or red alder may extend from riparian zones to adjacent uplands in an undifferentiated forest overstory. Wildlife populations include most typical riparian passerines, but raptors, wading birds, and other avian components of larger riparian systems are absent. Cutthroat (Salmoclarkii ) and steelhead (S . gairdneri ) trout and silver salmon (Oncorhynchuskisutch ) are common spawners within the streams and their tributaries (Humboldt County Planning Department 1978). Most riparian systems have been altered by timber harvest or fire, but many have gone through succession to relatively diverse second-growth forests.

Local coastal plans propose delineation of riparian corridors by assigning fixed distances from stream channels. For example, Humboldt County's southcoast area plan states:

Riparian corridors on all perennial and intermittent streams shall be, at a minimum, the larger of the following: (i) 100 feet, measured as the horizontal distance from the stream transition line on both sides; (ii) 50 feet plus four times the average percent of slope, measured as a slope distance from the stream transition line on both sides; (iii) where necessary, the width of riparian corridors may be expanded to include significant areas of riparian vegetation adjacent to the corridor, slides, and areas with visible evidence of slope instability, not to exceed 200 feet. (Humboldt County Planning Department 1981a)

Identification of riparian areas by vegetation analysis has not been proposed in any local coastal plan in the region because of the similarity of riparian and upland forest vegetation along these streams. Local agencies usually lack personnel trained in the vegetation identification and sampling techniques needed to differentiate riparian and upland systems based on hydrophytic understory components. In addition, the fixed distance riparian corridors proposed in these local coastal plans are familiar to most local residents and public officials because of their use in state and federal forest practices standards.

Uses in riparian corridors are usually limited to minor facilities and resource production, such as timber harvest, under standards designed to protect tree canopies and minimize erosion. Humboldt County's southcoast area plan provides that:

New development within riparian corridors shall be permitted when there is no less environmentally damaging feasible alternative, where the best mitigation measures feasible have been provided, and shall be limited to the following uses: (a) Timber management activities, provided that heavy equipment shall be excluded from the riparian corridor and where feasible, at least fifty percent of the existing tree canopy shall be left standing; (b) Timber harvests smaller than three acres of merchantable timber 18 inches

DBH or greater and non-commercial removal of trees for firewood provided that timber harvest practices shall be consistent with those permitted under the forest practices rules for stream protection zones in Coastal Commission special treatment areas. Where feasible, unmerchantable hardwoods and shrubs should be protected from permanent damage; (c) Maintenance of flood control and drainage channels; (d) Wells in rural areas; (e) Road and bridge replacement or construction, provided that the length of the road within the riparian corridor shall be minimized, where feasible, by rights of way which cross streams at right angles and do not parallel streams within the riparian corridor; (f) Removal of trees for disease control, or public safety purposes. Mitigation measures for development within riparian corridors shall, at a minimum, include replanting disturbed areas with riparian vegetation, retaining snags within the riparian corridor unless felling is required by CAL-OSHA regulation, and retaining live trees with visible evidence of current use as nesting sites by hawks, owls, eagles, osprey, herons, or egrets. (ibid .)

The riparian corridors protected by these policies can maintain habitats which provide "bridges" for wildlife movement between larger stepping stones and riparian islands. Protecting vegetation adjacent to streams can help protect water quality essential to anadromous fisheries. Because of the size of the areas protected and because some activities, such as logging under an approved timber harvest plan, are not regulated by these policies, such policies cannot be relied upon to protect all the riparian components necessary to maximize species diversity.

Policies to protect riparian corridors have met little resistance from landowners and local governments within the area. Most landowners can identify the fixed-distance corridor on their parcels and locate sites outside the corridor which are suitable for development. Local government officials can relate the protection of riparian corridors to local goals of protecting anadromous fisheries and domestic water quality, and so find them politically acceptable

Riparian Management in Remnant Vegetation Patches

Many local coastal programs propose protection of larger patches of riparian vegetation which may be located outside designated corridor areas. These patches are typically undisturbed old-growth forests with a diverse riparian flora and a vertically stratified physiognomy. Wildlife diversity within them may be limited because of their size or location adjacent to other developed uses. They play only a minor role in water quality or anadromous fisheries protection because they are typically located on broad alluvial plains and may be separated from the stream channel by other development. Many of these areas are located in state or federal parklands. Protection of these riparian areas is typically provided by public agencies which manage them.

Protecting similar patches on private lands has proven more difficult. The affected areas may be relatively large (2–10 ha.) and may seem unrelated to public goals for protecting fisheries or water quality. Consequently local officials have been reluctant to regulate such activities as timber harvests or conversion to agricultural use which may affect the habitat value of the area.

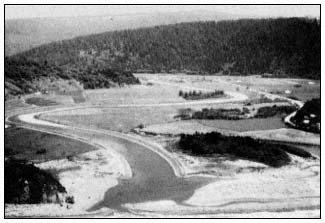

A patch of riparian vegetation at Redwood Creek in Humboldt County, of approximately 10 ha. (25 ac.), is typical of these sites (fig. 1). It includes a dense Sitka spruce/red alder stand which is the last remnant of Redwood Creek's old growth riparian forest. It has had little use as agricultural land and remained unharvested when adjacent riparian areas were converted to pasture. The Redwood Creek flood control project separated the site from the creek and provided access to it along the project's levees. Half of the patch is within Redwood National Park. Approximately 5 ha. (12 ac.) in its eastern half are owned by a local cattleman as part of a larger ranch.

Figure 1.

Remnant patches of riparian vegetation, Redwood

Creek, Humboldt County, California.

The local coastal plan (Humboldt County Planning Department 1980a) designated the area for agricultural use and only proposed protection of vegetation within the 30.5 m. (100-ft.) riparian corridor. The owner had no plans to develop or convert the remainder of the site, but resisted land-use policies which required its protection for habitat use. The regional commission did not approve the plan, but stated that it would ap-

prove a revised plan which designated the site for natural resources use and limited new development on it to habitat management and tree removal for firewood purposes under certain conditions. The protection plan for the site recommended by the regional commission will probably be accepted by the landowner and the local government because of the parcel's isolation and its relatively small size. By permitting firewood harvesting, traditional woodlot uses of the stand were maintained, providing some economic return to the property owner.

Patches of riparian vegetation such as this site can provide the stepping stones to connect larger habitat islands. The areas themselves provide habitat for wading birds and cavity nesters which are not common inhabitants of the narrower riparian corridors along small coastal streams. These patches are probably not large enough to accommodate minimum area species such as large raptors or to sustain sufficient numbers of individuals to maintain healthy breeding populations of many smaller riparian species. Those species which depend on such specific conditions as dense canopies or dead or dying wood in snags or on the forest floor may be displaced in the future if firewood harvesting reduces these habitat components. Nonetheless, both types of birds could use the area for resting or foraging while traveling between larger riparian areas.

Management of Large Riparian Systems

Preparing local coastal plans for large riparian systems—the habitat islands for ripariandependent species—has proven to be one of the most difficult tasks facing local governments and the Coastal Commission.

Protecting these riparian areas is particularly troublesome because of the need to maintain the areas in a virtually undisturbed state in order to retain unique habitat components such as dense canopies or dead and down trees. While state and federal wildlife refuges, parks, conservation areas, and wilderness areas provide large blocks of relatively undisturbed wetland, upland forest, or montane vegetation, there are no comparable publicly-owned riparian reserves within the coastal zone in the northcoast region. Protecting these areas will require either public purchase or extensive regulation of substantial amounts of private land. Public purchase is unpopular because of agency financial constraints, effects on local tax bases, and resentment over the already large public land holdings in the region. Local governments are generally unwilling to adopt the strict regulations necessary to protect these areas because the regulations may affect landowners who are frequently representatives of important segments of the local economy.

Constitutional issues (including questions of taking land without compensation) have not been extensively litigated in cases involving riparian vegetation, and most local governments are hesitant to expose themselves to potential legal and financial liabilities. Finally, because most data on riparian system values are from areas other than the northcoast and are not well understood by the general public, local support for protecting large riparian systems is limited.

Three areas provide examples of the problems presented to local governments and the Coastal Commission in managing these large riparian systems.

Elk Creek, Del Norte County

Elk Creek is located immediately northeast of Crescent City, and has a drainage basin covering approximately 1,670 ha. (4,120 ac.). It originates in the upland forests of Jedediah Smith Redwoods State Park and flows into the Crescent City harbor.

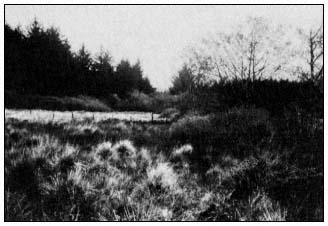

Approximately half of the watershed and almost all of the private lands within the Elk Creek basin, are within the coastal zone. About 225 ha. (550 ac.) of the coastal zone portion of the watershed are forested riparian zones, characterized by Sitka spruce, redwood, western hemlock (Tsugaheterophylla ), red alder, and Pacific wax-myrtle (fig. 2). These forests meet freshwater marshes along the creek in an ecotone dominated by willows, Douglas spirea (Spiraeadouglasii ), and twinberry (Lonicerainvolucrata ). Wildlife within the area includes such riparian-dependent species as Red-shouldered Hawk (Buteolineatus ), Snowy Egret (Leucophoyx thula), and Great Blue Heron (Ardea herodias ) (Del Norte Planning Department 1980). The area has been logged, and approximately 15% of its forested lands has been converted to pastureland. Major portions of its basin, including many riparian areas, have been subdivided to parcels of 2 to 8 ha. (5 to 20 ac.) for rural residential use. However, soil moisture has permitted succession of both second-growth forests and abandoned fields to well-developed riparian vegetation. With the extensive clearing of

Figure 2.

Riparian vegetation on Elk Creek, Del Norte County, California.

riparian vegetation along Smith River and at Earl and Talawa lakes, Elk Creek is the principal alluvial riparian system remaining in Del Norte County.

The local coastal plan designated riparian zones in the Elk Creek drainage for a mix of agricultural general, timberland, and woodlot uses.[5] Those portions of the riparian areas which are frequently flooded were identified as wetlands. The plan included the following policies affecting riparian systems in the Elk Creek watershed:

(1) The filling, dredging or diking of any portion of the Elk Creek wetlands shall be prohibited except where necessary for flood control purposes; or when such activity enhances the biological productivity of the marshland; or when compatible with other policies of the coastal program and a specific finding is made which cites that policy;

(2) A buffer strip shall be maintained in natural conditions around the Elk Creek wetlands;

(3) No permanent structures shall be constructed within the identified portions of the Elk Creek wetlands including any delineated buffer zone;

(4) New development adjacent to the Elk Creek wetlands shall not result in adverse levels or additional sediment, runoff, noise, wastewater or other disturbances;

(5) Snags shall be maintained within the Elk Creek wetland for their value to wildlife;

(6) Riparian vegetation along the course of Elk Creek and its branch streams shall be maintained for their qualities of wildlife habitat and stream buffer zones;

(7) Vegetation removal in the Elk Creek wetland shall be limited to that necessary to maintain the free flow of the drainage courses;

(8) The County should encourage and support educational programs in schools, park programs and community organizations which seek to increase public awareness and understanding of sensitive habitats and the need for their protection. (ibid .)

The regional commission did not approve the land-use plan because of the designation of sensitive riparian lands for potential development, even though at low densities, and the absence of a specifically defined buffer zone. The regional commission stated that it would approve the land-use plan if the county redesignated riparian zones as resource conservation areas, within which residential development was prohibited and parcels in contiguous ownership were merged, and adopted a minimum 100-ft. buffer zone around these lands.

As approved, the land-use plan prohibits development (including removal of vegetation except for flood control) on all riparian lands. Commercial timber harvests are not regulated by the plan; thus protection of riparian vegetation relies in large part on the designation of areas adjacent to riparian areas for rural residential use and other development at 1 unit per 8 ha. or more. The subdivision of these lands makes intensive forestry less feasible due to the loss of economics of scale necessary for long-term commercial timber production. This solution was acceptable to the county—the county relies primarily on public forest lands for its timber production (Proctor etal . 1980)—and was approved by the Coastal Commission because it reflected existing development trends in the area without jeopardizing the habitat values of the creek. Constitutional questions were minimized by merging adjacent parcels to provide larger lots where development could be sited on uplands beyond the buffer zone. The plan relies in large part on the inaccessibility, high water table, and lack of development pressure at Elk Creek to protect its riparian elements.

Eel River, Humboldt County

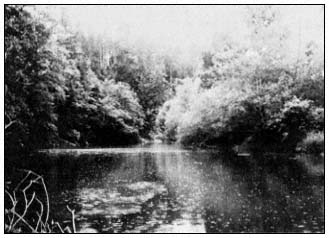

The Eel River flows from Mendocino and Humboldt County to enter the Pacific Ocean approximately 19 km. (12 mi.) southwest of Eureka. It enters the coastal zone near its junction with the Van Duzen River, and has a drainage basin of 923,000 ha. (2.28 million ac.). About 8,100 ha. of its watershed are within the coastal zone (fig. 3). Approximately 1,000 ha. of this area are forested riparian systems dominated by red alder, willow, and black cottonwood. Dense willow stands are common in areas with high water tables or subject to frequent high velocity water flows. Typical wildlife in the area includes all species previously identified plus additional species of cavity-nesting ducks, and raptors such as the White-tailed Kite (Elanusleucurus ) and Peregrine Falcon (Falcoperegrinus ), which hunt over adjacent farmlands. Winter raptor populations in the area are particularly high—as little as 1.3 km. of transect per bird[6] —due in large part to the availability of riparian, wetland, and pasture vegetation in the area. Over 110 bird species dependent on riparian areas for some portion of their habitat requirements have been identified in the area.

[5] Agricultural general use provisions permit residential development at 1 unit per 8 ha. (20 ac.) and related development for grazing use, such as barns. Timberlands are intended for commercial timber use. Divisions to 1 unit per 8 ha. are permitted. Woodlot areas are forested rural residential lands with development permitted at 1 unit per 0.8 ha. (2 ac.).

[6] Pierce, H. 1981. Personal correspondence. California Department of Fish and Game, Eureka.

Figure 3.

Eel River delta, Humboldt County, California. Riparian

vegetation is located adjacent to the main stem

of the river (photo courtesy of NASA).

These riparian lands are a small remnant of the approximately 4,000 ha. (10,000 ac.) of the redwood/Sitka spruce/black cottonwood forest that occupied the Eel River delta floodplain at the advent of human settlement. Most of these lands were converted to grazing use because of their highly productive soils. Together with pasturelands on diked tidal marshes, they account for over half the cultivated agricultural land in Humboldt County's coastal zone and are the heart of the county's dairy industry (Humboldt County Planning Department 1979). Where forested riparian zones remain along the river, they are restricted to either the immediate channel corridor or to one of three large vegetation blocks located on oxbows, islands, or major turns in the river. Within these areas, conifers, which show clearly in historic photos of the same locations, are scarce. Portions of these areas were highly disturbed by flooding in 1955 and 1964. Aerial photos of the area show that mature red alder/black cottonwood forests occupy 33% of its riparian systems, followed by young black cottonwood/red alder stands occupying 23%, mixed red alder/willow stands occupying 32%, and grassland/forb pastures with scattered willows and red alder occupying 12%.

The retention of this vegetation pattern is in large part due to deliberate decisions by riparian landowners in response to past experience with flood damage and bank erosion. Eel River farmers have stated that most areas of black cottonwood/red alder vegetation have been retained because of their value in controlling flood-borne drift and coarse sediments which damage adjacent agricultural lands and structures. Most young red alder/willow patches are flood-damaged pastures abandoned after the 1955 or 1964 floods. Landowners of these sites may lack sufficient capital to reclaim the land. Where floodwaters deposit coarse sediments, property owners rely on riparian vegetation to slow the floodwaters, allowing them to drop finer soil particles. Some landowners have retained or even planted willow areas to retard bank erosion.

Most landowners have resisted policies which require retention of existing riparian vegetation. Increased wood chip or pulp wood prices may entice some owners of black cottonwood/red alder stands to harvest their riparian forest lands, even at the risk of increased flood damage. If the owners do not farm on valley pasturelands, there is little incentive to maintain mature forest stands. Where mixed red alder/willow stands occupy flood-damaged areas, property owners may anticipate additional silt deposition, or capital savings may permit reclamation of the site for agriculture. Local farmers have stated that several of these areas have gone through successive cycles of flood damage, forest growth, and clearing since the 1900s. Where construction of bank protection or changes in the river channel have reduced erosion hazards, property owners may decide to clear willow stands. Few landowners are willing to forego such uses as selective timber harvest or firewood removal, which retain riparian woodland stands but damage some habitat components essential to the area's diverse wildlife populations. Finally, almost all landowners wish to retain maximum flexibility of land use to respond to the dynamics of an area where, as one farmer stated: "The Eel owns the first mortgage and the bank gets the second" (Humboldt County Planning Department 1980b).

The Humboldt County Planning Department (1981b) recommended a local coastal plan focused on protecting old-growth black cottonwood/red alder stands, restoring degraded riparian systems, potentially converting some willow/alder stands, and retaining a forested riparian corridor along the river channel. The policies provided:

(1) The total acreage of the riparian corridor shall be established as a minimum base line for riparian vegetation on the Eel River; (2) Three areas of older age class riparian vegetation, comprised of old cottonwoods and alders, are designated Natural Resource. These areas are significant wildlife habitats and are critical to flood protection of adjacent prime agricultural lands and maintenance of the present river channel locations. To insure long term protection of these resources, the County encourages the purchase of these lands in fee title or through easements from willing sellers. Permitted uses within the Natural Resources designation include management for fish and wildlife, development of hunting blinds and similar minor facilities, and removal of trees for

firewood, disease control, or public safety purposes. (3) Removal of riparian vegetation outside the three Natural Resource areas is subject to the following policies: (A) The total acreage of the riparian vegetation shall be maintained by: (i) Encouraging the replanting of riparian vegetation from the stream transition line to the river channel; (ii) Planting of riparian vegetation as part of bank protection projects; (iii) Prohibiting conversions of riparian woodlands to other uses which would decrease the total amount of riparian vegetation below the minimum base line amount, or which would clear riparian vegetation within 200 feet of the stream transition line; and (iv) Limiting removal of vegetation, other than conversions, to timber management, selective timber and firewood harvests, and other minor or incidental uses. (ibid .)

The proposed land-use plan would protect the principal riparian systems from conversion to agricultural use. By encouraging replanting of unvegetated riparian areas and permitting conversion of some younger stands of riparian vegetation only if the total acreage of riparian vegetation on the river increased above existing levels, the plan provides incentives for restoring riparian woodlands on underutilized farmlands or flood-damaged river bars. These policies and those which tie riparian corridors to the river's stream transition line, permit adjustment of protected riparian areas with changes in either the river channel or vegetation patterns. The plan maintains traditonal use of mature riparian stands, including firewood cutting, and identifies additional economic uses such as commercial timber management and harvest in other riparian areas.

The proposed plan has not gained the approval of either fish and wildlife agencies or local agricultural interests and their representatives on the County's Planning Commission. The DFG has criticized the plan for permitting such uses as firewood harvests or timber management, which may remove important habitat components or change the composition of tree species in riparian areas. The DFG pointed out the uncertainty of long-term maintenance of restored riparian systems due to damage by high velocity floodflows or erosion, arguing that conversion of existing stands in exchange for restoring damage-prone areas may result in a long-term reduction in riparian acreage.

Agricultural interests, on the other hand, believe that restricting large areas to natural resource use deprives them of reasonable economic returns from their land holdings. They point out that neither the county nor other agencies have identified funding sources for public purchase of the Natural Resource areas. Most farmers realize the difficulty of any riparian restoration program, and their own limited ability to reclaim riparian areas for agricultural use. Lands suitable for restoration may not even be located on parcels in the same ownership as those proposed for conversion, necessitating a complex process of land acquisition, leaseholdings, etc.

The plan's potential to protect riparian systems is also undermined by the county's limited responsibility under the Coastal Act to control commercial timber harvests. Commercial timber harvests approved by the Department of Forestry (DF) are not subject to regulation by local coastal programs, and large expanses of riparian vegetation may be harvested for woodchips.[7]

Because the Coastal Commission did not anticipate the effect of chip price increases on the value of the Eel River's riparian woodlands, it did not designate the river's riparian systems as special treatment areas (see discussion of Big River below). Present timber harvest rules offer little protection for the area's riparian values.

Important information necessary to the plan's implementation is lacking. Sites suitable for restoration of riparian vegetation, successful restoration techniques, or funding sources for restoration programs have not been identified. Standards for commercial timber management or firewood harvests which can provide both economic uses and habitat protection have not been identified. Timber management techniques from European or eastern hardwood stands may be applicable (e.g., see Stewart 1981). However, local residents, foresters, and biologists are unfamiliar with these techniques, and their likely impact on wood production or habitat protection is not known.

The Eel River lacks the components which led to agreement on riparian protection for Elk Creek. The Eel River's riparian systems hold resources important to local interest groups and for which substitutes are not available. High soil productivity and exposure to flood hazards make protection of riparian areas as part of residential development infeasible. The absence of special treatment area standards for timber harvest plans leaves the area exposed to significant habitat damage during commercial logging. It appears that a plan lacking a substantial

[7] Red alder may be considered a commercial species in timber harvest plans at the option of the professional forester preparing the plan. Black cottonwood and willow are not subject to timber harvest plans. Because of these administrative guidelines and local government's absence of jurisdiction over logging under timber harvest plans, the county can assure protection of only some components of the riparian systems. The degree of protection will be in large part determined by landowners' decisions to file timber harvest plans for red alder stands, or to manage them for other uses consistent with the county's plan.

public funding committment for purchase of riparian woodlands will not ensure protection of the Eel River's habitat values.

Big River, Mendocino County

Big River, with a drainage basin area of approximately 42,500 ha. (105,000 ac.), is located in central Mendocino County and drains into the ocean through an estuary extending up to 13 km. (8 mi.) above the river's entrance to Mendocino Bay. Approximately 1,500 ha. of the drainage basin are located within the coastal zone. Big River is a drowned river valley rather than a broad alluvial flat.

Riparian systems at Big River are characterized by dense, mature second-growth redwood forests with an understory of grand fir (Abiesgrandis ), red alder, California nutmeg (Torreyacalifornica , and tanoak (Lithocarpusdensiflorus ). Red alder dominates riparian areas on natural levees between the estuary and the redwood forest (fig. 4). Willows, Oregon ash (Fraxinuslatifolia ), and cascara (Rhamnuspurshiana ) are common in alder-dominated forests. Adjacent uplands are coniferous forests with Douglas fir (Pseudotsugamenziesii ), redwood, and western hemlock (Warrick and Wilcox 1981).

Figure 4.

Riparian vegetation on Big River, Mendocino County.

Seacat, Seymour, and Marcus (Warrick and Wilcox 1981) identified 10 bird species in mature redwood forest and 23 species in harvested redwood forests. Species lists for the Big River area include most wading birds and waterfowl which nest or roost in riparian systems, but lack the diverse raptor populations found at Elk Creek and Eel River.

Timber has been harvested at least once in most of the river's watershed. Warrick and Wilcox (ibid .) reported that red alder-dominated riparian forests have increased along the river channels, in what were previously estuarine systems, due to accretion of sediments generated by upriver timber harvests.

Mendocino County's local coastal plan designates alder-dominated forests as riparian vegetation. Redwood forests, together with upland redwood/Douglas-fir communities are designated for forest use. Policies for their development include:

(1) Development within 100-foot wide riparian corridors adjoining perennial and intermittent streams and riparian vegetation shall be regulated by Policy 2. Riparian corridors shall be measured from the landward edge of riparian vegetation, or, if no vegetation exists, from the top edge of the stream bank; (2) No structure or development, including dredging, filling and grading, which could degrade the riparian area or detract from its value as a natural resource shall be permitted in the riparian corridor except for: measures necessary for flood control; pipelines, utility lines and road crossings; timber harvesting operations, as regulated by the Forest Practices Act; and collection of firewood, if not more than 25 percent of the forest canopy is lost to cutting over a ten year period; (3) The implementation phase of the LCP shall include preparation of performance standards and/or recommendation of mitigation measures applicable to allowable development within riparian corridors. These standards and measures shall minimize potential development impacts such as increased runoff, sedimentation, biochemical degradation, increased stream temperatures and loss of shade caused by development. When development activities require removal or disturbance of riparian vegetation, replanting with appropriate native plants shall be required; (4) Where riparian vegetation exists away from stream corridors, development shall be minimized; (5) In timberland units of commercial size, permitted uses shall be limited to timber production and related harvesting and processing activities; seasonal recreational uses not requiring permanent structures; management of land for watershed maintenance, grazing and forage, and fish and wildlife habitat; construction and maintenance of gas, electric, water or communication transmission facilities; and residential uses as described in Policy 6; (6) Parcels entirely occupied by timberlands of commercial size shall have not more than one housing unit per 160 acres or 4 units per parcel. (Blayney-Dyett 1980)

Riparian systems of Big River are located entirely on unroaded floodplains with high water tables, and residential development on them is

improbable. In this regard, they are much like riparian areas at Elk Creek. Unlike Elk Creek, however, Big River's riparian systems are extraordinarily productive commercial timberlands which provide a significant portion of the coastal Mendocino County sawlog resources. They are owned by a major timber company whose Fort Bragg sawmills provide a substantial percentage of employment in the area.

All riparian forests and some of the adjacent uplands at Big River were designated as forestry special treatment areas. Commercial timber production is the most likely use of this riparian vegetation, and the California Board of Forestry's timber practice rules for Coastal Commission special treatment areas will be central to protecting habitat values of this vegetation. In addition to the practices prescribed for all timber harvests in the Coast Forest District, the rules generally require: (1) protection of live trees with visible evidence of current nesting by endangered species, raptors, waterfowl, or wading birds. Forest practice rules outside of special treatment areas only require protection of endangered species nesting sites, and encourage protecting trees used as nesting sites by eagles and osprey; (2) stream protection zones 46 m. (150 ft.) wide on each side of perennial streams and 30 m. (100 ft.) on each side of intermittent streams. Within these stream protection zones, 50 to 70% of the total tree canopy and 50% of all other vegetation must be left standing. Forest practice rules outside of Coastal Commission special treatment areas require stream protection zones 30 m. (100 ft.) wide on perennial streams and 15 m. (50 ft.) on intermittent streams, within which 50% of the stream-shading canopy must be left standing; (3) a 4 ha. (10 ac.) maximum limitation on clear-cut size. Clear-cuts outside of special treatment areas are limited to a maximum 32 ha. (80 ac.) size.

These timber practice rules can mitigate harvest impacts on many components of Big River and other coastal riparian forests. Rules which protect nesting sites or tree canopies and other vegetation adjacent to the river and its tributaries can maintain feeding, nesting, and roosting sites for riparian wildlife. Limiting clear-cut size can reduce the effects of timber removal outside the stream protection zones, providing a variety of habitat-types as large timberland areas are rotated through successive cycles of harvest and forest growth. However, the rules cannot ensure protection of old-growth vegetation or long-term maintenance of such unique habitat components as snags, which are essential to some riparian wildlife. Nor can they protect riparian systems from the adverse impacts of timber harvests beyond the boundaries of the special treatment area.

Protecting riparian systems at Big River by acquisition is unlikely. In 1979, the USDI Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) proposed acquiring up to 610 ha. (1,500 ac.) of the Big River watershed including both red alder and redwood riparian areas (USDI Fish and Wildlife Service 1979). Acquisition was not supported by the Coastal Commission which, in its comments on the proposal, cited Coastal Act policies preventing conversion of commercial timberlands to other uses. The acquisition proposal was opposed by the landowner and Mendocino County, both of which feared adverse effects on sawlog supplies for the company's Fort Bragg mill. The proposal was eventually withdrawn by the FWS due to this local opposition and, perhaps, the rapid escalation of redwood timberland prices following the Redwood National Park expansion.

Conclusion

These examples demonstrate the potentials and limitations of regulatory land-use controls in protecting riparian systems. Even an agency with the broad regulatory authority of the Coastal Commission is limited in its ability to protect riparian areas. The limitations are due in part to conflicting objectives—a problem which besets most resource management agencies. The Coastal Commission's limited jurisdiction over timber harvests has presented both opportunities and constraints to the Commission's ability to protect northcoast riparian forests. The Commission has been relatively successful in protecting riparian corridors along small coastal streams and larger patches of riparian vegetation. In the northcoast region, however, its ultimate ability to maintain large riparian systems is in doubt, partly due to limited public understanding of these values and partly to the reluctance of local government to restrict large areas to wildlife habitat use. This reluctance is attributable both to goals of increased economic development and concerns about constitutional protection of property rights. Protecting large, coastal riparian systems through land-use regulation may be successful where these limitations can be overcome. In some areas, effective protection can be achieved only through public purchase. However, even when acquisition funding is available, other social goals may make protection of large riparian systems infeasible.

What do these lessons from the coastal zone suggest for others interested in protecting riparian systems? First, protection must begin with improved information about habitat processes in riparian areas. That information must be effectively transferred to the public. Current developments in wetland protection, for example, are the result of decades of research and public education through sportsmen, conservationists and public information programs. Similar efforts for riparian ecosystems are only beginning.

Second, land-use regulation can successfully protect small riparian areas, but can rarely do more than mitigate impacts in large systems. With effective land-use policies and adequate agency jurisdiction, large riparian areas can be protected from conversion. Forest practice rules can be effective in mitigating the impacts of timber harvest on many components of riparian

systems. Extending forest practice rules to cover harvesting of riparian hardwoods and incorporating features of the harvest standards for Coastal Commission special treatment areas into the management of all riparian woodlands would reduce damage to habitat values. In addition, amendment of the forest practice rules to take into consideration critical riparian habitat features by providing, for example, adequate long-term snag recruitment and maintenance of dead and down wood, would help protect wildlife populations dependent on these special habitat components.

Third, a long-term acquisition program for critical riparian systems will be necessary to protect areas where regulation is infeasible or inadequate. Any acquisition program should be based on a statewide or regional assessment of long-term habitat protection objectives, rather than a response to immediate "brushfires". The FWS concept plan for waterfowl wintering habitat preservation is a good example of a long-term program for habitat protection.

Finally, you can't win them all. Some important riparian systems will not be protected despite strong land-use planning and well-planned acquisitions. Wildlife agencies should begin planning to restore degraded riparian areas, to compensate for these unavoidable losses. Potential restoration sites should be identified and restoration activities begun. Within the northcoast region, degraded riparian areas suitable for habitat restoration are located on many existing public lands. Such a restoration program may prove more effective in compensating for unavoidable damage to riparian ecosystems than recommendations for extensive mitigation as part of development projects and could take advantage of funding from a variety of sources, including in-lieu fees collected from projects which degrade riparian areas.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Herbert Pierce, Thomas Stone, and Gary Monroe, California Department of Fish and Game; Bruce Fodge, California Coastal Commission; and Donald Tuttle and Patricia Dunn, Humboldt County Public Works and Planning departments, for their interest and assistance in the development of the data, concepts, and land-use policies discussed in this report.

Literature Cited

Blayney-Dyett. 1980. Coastal element, Mendocino County general plan. 191 p. California Coastal Commission, San Francisco, Calif.

Del Norte County Planning Department. 1980. Local coastal program land use plan. 384 p. Del North County Planning Department. Crescent City, Calif.

Forman, R.T.T., A.E. Galli, and C.F. Leck. 1976. Forest size and avian diversity in New Jersey woodlots with some land use implications. Oecologia 26:1–8.

Galli, A.E., C.F. Leck, and R.T.T. Forman. 1976. Avian distribution patterns in forest islands of different sizes in central New Jersey. Auk 93:356–364.

Gates, J.E., and L.W. Gysel. 1978. Avian nest dispersion and fledging success in fieldforest ecotones. Ecology 59:871–883.

Harris, S.W. 1973. Birds and their habitats in the mid-Humboldt region. 22 p. Unpublished report. On file at Humboldt State University, Arcata, Calif.

Humboldt County Planning Department. 1978. Habitats sensitivity technical study. 103 p. Humboldt County Planning Department. Eureka, Calif.

Humboldt County Planning Department. 1979. Agriculture technical study. 23 p. Humboldt County Planning Department. Eureka, Calif.

Humboldt County Planning Department. 1980a. North-coast area plan. 75 p. Humboldt County Planning Department. Eureka, Calif.

Humboldt County Planning Department. 1980b. Eel River area plan. 100 p. Humboldt County Planning Department. Eureka, Calif.

Humboldt County Planning Department. 1981a. South-coast area plan. 74 p. Humboldt County Planning Department. Eureka, Calif.

Humboldt County Planning Department. 1981b. Staff recommendation—Eel River area plan. 16 p. Unpublished report. On file at Humboldt County Planning Department, Eureka, Calif.

Leipzig, P. 1972. Wildlife inventory, midHumboldt County area. Unpublished report. 15 p. On file at Humboldt State University, Arcata, Calif.

Mac Arthur, R.H., and E.O. Wilson. 1967. The theory of island biogeography. Princeton monogr. in Pop. Biol. No. 1, Princeton University Press, Princeton, J.J. 203 p.

Marcot, B.G. (ed.). 1979. California wildlife/habitats relationships programs—North Coast/Cascades zone. Vol. 1–5. 1136 p. Six Rivers National Forest, USDA Forest Service, Eureka, Calif.

Monroe, G.W. 1974. Natural resources of the Eel River delta. California Department of Fish and Game, Coastal Wetlands series No. 9, Sacramento, Calif. 108 p.

McLaughlin, J., and F. Harradine. 1965. Soils of western Humboldt County. 84 p. Department of Soils and Plant Nutrition, University of California, Davis.

Pickett, S.T.A., and J.N. Thompson. 1978. Patch dynamics and the design of nature reserves. Biol. Conserv. 13:27–37.

Proctor, C.M., J.C. Garcia, D.V. Gaulin, T. Joyner, G.B. Lewis, L.C. Loehr, and A.M. Massa. 1980. An ecological characterization of the Pacific Northwest coastal region. Vol. 1–5. USDA Fish and Wildlife Service, Biological Services Program. FWS/OBS-79/11 through 79/15. Washington, D.C.

Roberts, W.G., J.G. Howe, and J. Major. 1977. A survey of riparian forest flora and fauna in California. p. 3–20. In : A. Sands (ed.). Riparian forests in California—their ecology and conservation. Institute of Ecology Pub. No. 15. 122 p. University of California, Davis.

Schoener, T.W. 1968. Sizes of feeding territories among birds. Ecology 49:123–141.

Stewart, P. 1981. Coppicing with standards. Coevolution Quarterly 30:56–61.

Strahler, A.N. 1964. Quantitative geomorphology of drainage basins and channel networks. Section 4.2. In : Ven to Chow (ed.). Handbook of applied hydrology. McGraw-Hill, New York, N.Y.

Thomas, J.W. (ed.). 1979. Wildlife habitats in managed forests—the Blue Mountains of Oregon and Washington. USDA Forest Service Agricultural Handbook No. 553, Washington, D.C. 512 p.

Thompson, K.E., A.K. Smith, and J.E. Lauman. 1972. Fish and wildlife resources of the southcoast basin, Oregon, and their water requirements (revised). Oregon State Game Commission, Portland, Oregon.

USDA Forest Service. 1965. Soil-vegetation survey of Mendocino County. Pacific Southwest Forest and Range Experiment Station, USDA Forest Service, Berkeley, Calif.

USDI Fish and Wildlife Service. 1979. An environmental assessment of the Big River estuary, Mendocino County, California. 52 p. USDI Fish and Wildlife Service. Sacramento, Calif.

Warrick, S.F., and E.D. Wilcox (ed.). 1981. Big River—the natural history of an endangered northern California estuary. Environmental Field Program Pub. No. 6. 296 p. University of California, Santa Cruz, Calif.

Wilcox, B.A. 1980. Insular ecology and conservation. p. 95–117. In : M.E. Soulé and B.A. Wilcox (ed.). Conservation Biology. 305 p. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, Mass.